Key Points

-

If diagnosed early, interceptive extraction of the deciduous canine can correct the path of eruption of the permanent canine and prevent impaction.

-

GDPs have a key role in the early detection and referral of such cases.

-

In this audit, GDP referral practice for patients with impacted maxillary canines was generally poor.

-

Clinical guidelines even with some additional supporting education were ineffective in improving the referral practice.

-

Further investigation is required of alternative methods to improve the uptake of such information.

Abstract

Objective To assess referral practice for patients presenting with impacted palatal maxillary canines, and to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of referral guidelines.

Design Prospective clinical audit.

Setting Southend and Basildon district general hospitals.

Subjects and methods The 'gold' standard was identified as regular dental attenders with unerupted palatal canines being referred by 12 years old, with a wait of no longer than 20 weeks from referral to assessment. Data were collected and compared to the defined standard. An algorithm outlining the correct management was developed and distributed to all local dentists. The cycle was repeated for a similar time period.

Results Ninety-eight per cent of patients were seen within 20 weeks during both cycles while the referrals increased from 85 to 109 patients. The percentage of patients referred by 12 years of age increased from 16.5% to 27% (p = 0.09). During the first cycle 82% of patients presented with retained deciduous maxillary canines. This was reduced to 76% during the second cycle (p = 0.29).

Conclusion Referral practice was generally poor when compared to the recommended good practice. More patients were referred after distribution of the guidelines, but the percentage referred by the recommended age was not statistically significantly improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the exception of the third molars, the maxillary canine is the most frequently impacted tooth.1,2 The incidence ranges between 0.92–2%3,4 and is twice as common in females than males.5 Eighty-five per cent of impactions are palatal, while the remaining 15% are buccal.6,7

The aetiology of palatal impactions is unclear but appears to differ from buccally positioned canines, which are usually impacted due to inadequate arch space. Possible causes include the long developmental path of eruption of the maxillary canine,2,8 the lack of guidance from the adjacent lateral incisor root9,10,11 and ectopic development of the tooth by polygenic inheritance patterns.12,13

If left untreated, the potential risks associated with palatal impactions include resorption and possible loss of the adjacent permanent teeth. The reported incidence of incisor root resorption caused by ectopic canines varies between 12.5-48%.7,14

Prevention of an impaction is always preferable to its treatment. Management of impactions usually requires surgical intervention to remove the tooth or expose it. Exposure is followed by prolonged orthodontic treatment to align the canine. Treatment is complicated, and has considerable time and cost implications.15,16 Furthermore, the consequences of such treatment can compromise the periodontal health of the canine tooth.17

Case reports have shown that if diagnosed early, interceptive measures may correct the eruption path of the permanent tooth and prevent impaction.8,18,19,20,21,22 Furthermore, Eriksson and Kurol23 showed in a prospective trial that 78% of palatally impacted canines erupted following removal of the deciduous predecessor in uncrowded arches before the age of 11 years. These findings were later supported by a similar investigation in both crowded and uncrowded malocclusions.24 Both studies showed that the outcome was dependent on a number of variables including the patient's age at diagnosis. Bruks and Lenartsson25 retrospectively compared palatally displaced canines referred for specialist treatment with those successfully treated by the general dental practitioner by interceptive extractions. Their findings suggested that up to one third of the cases referred for specialist treatment could have benefited from the interceptive extraction of the deciduous canines had they been diagnosed earlier. Age at the time of diagnosis and referral appeared to be the most important factor in determining the final outcome.

Early diagnosis is the responsibility of the general dental practitioner. This should be based on a combination of clinical and radiographic examination. Early detection of the maxillary canine's possible position can be made in patients as young as 9-10 years old. An ectopic or impacted canine may be suspected when there is no canine bulge in the labial sulcus by the age of 12 years, or if there is asymmetry on palpation or a pronounced difference in the time of eruption. Radiographic examination is essential to locate the position of the tooth, and assess the health of adjacent teeth.

Aim

A subjective opinion was formed that many patients were being referred later than they should be. The aims of the first audit cycle were therefore to:

-

Establish whether local general dental practitioners (GDPs) had diagnosed the problem and appropriately referred the patient.

-

Determine whether hospital waiting list times had significantly delayed the initial patient consultation.

-

Following the audit, referral guidelines were developed. The re-audit therefore aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the guidelines in improving GDP referral behaviour.

Method

A prospective two-centre audit was undertaken at Basildon and Southend hospitals between September 2001 and September 2003. An audit cycle was first established. The gold standard to be met was defined as:

-

Patients who are regular attenders with unerupted palatal canine teeth should be referred by the age of 12 years. This was based upon the available scientific literature discussed in the introduction.

-

There should be a wait of no longer than 20 weeks from referral to being seen. This was based upon the department of health outpatient waiting time target at the time of the second audit cycle.

-

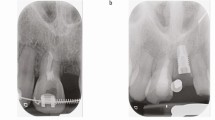

The date at which the referral was made was used to determine the subject's age. To allow assessment of local practice, data were collected for each patient over a 12-month period (Fig. 1). These findings were compared to the standard, following which an information letter outlining the reasons for early detection and criteria for referral of palatally impacted canines was sent to all local GDPs. The information was presented in the form of a user-friendly algorithm (Fig. 2). The audit was then repeated for a similar period of time.

Statistics

Differences in the age of referral, and the presence of deciduous maxillary canines between the two audit cycles were assessed using the chi-squared test.

Results

These are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,6. The percentage of patients referred by the age of 12 years increased from 16.5% to 27% following introduction of the guidelines. However, statistical analysis using the chi-squared test revealed that there was no difference in the proportion of patients being referred by the appropriate age (p = 0.09).

The number of patients presenting with retained maxillary canine teeth was assessed to obtain some idea of whether any interceptive extractions might have been undertaken by the GDP. While the percentage of patients presenting with retained deciduous canines decreased from 82% in the first cycle to 76% during the second cycle, chi-squared analysis revealed that this was not a significant finding (p = 0.29).

Discussion

This audit showed a 28% increase in the total number of patients referred following implementation of the guidelines. This may have been a reflection of the referring dentists' increased awareness in the management of such patients. From this point of view, development and implementation of the guidelines could be considered a success. However, there is also the possibility that other factors such as changes in the local practitioner profile could be responsible for the changes observed.

It is also important to bear in mind that the second cycle may have included patients that were missed in the past. They may subsequently have been picked up as a result of the guidelines, albeit at an older age. With this in mind, a future third cycle might more accurately assess whether practice has improved. Overall however, there was no evidence to suggest that the guidelines produced a statistically significant improvement in the appropriateness of the referrals made.

The results of this audit showed that despite the provision of guidelines based on the current evidence, the overall referral pattern was poor. Although the problem had been diagnosed in 95% of all patients referred, 73% were still referred after the recommended age of 12 years. These results are disappointing especially when one considers that the correct referral of such patients forms the basis of any undergraduate orthodontic teaching programme and should represent basic care.

The number of 12 year olds within the Primary Care Trusts covered by these hospitals is approximately 8,000. If a 1-2% incidence of palatal canine impactions is considered3,4 one could assume that there may be between 80-160 12 year olds affected. During the second cycle only 29 patients were actually referred. There is the possibility that some of the more straightforward cases could have been treated in specialist practice, so even this method of ascertaining how many patients should be referred to us is flawed.

The presence of deciduous canines was taken as evidence of a lack of any attempt to provide interceptive treatment by the GDP. Indeed, this may provide an overly optimistic picture of GDP interception, as some deciduous teeth will have exfoliated naturally rather than by interceptive treatment. However, as many patients could not recollect their past dental history accurately enough to record the reason for an absent deciduous canine this could not be assessed.

The difficulty in impacting change in the referral practice of practitioners through the use of orthodontic guidelines has been previously highlighted.26 Other randomised clinical trials have shown that implementation of guidelines in medical primary care are variably effective.27,28,29,30 Furthermore, recent systematic reviews suggest that the effects of audit and feedback in improving professional practice are generally variable.31,32

These guidelines were developed to address the shortcomings in referral practices identified in the first audit cycle. Studies that have reviewed the effectiveness of guideline development and implementation highlight many variables, which may have factored in the lack of any significant result in this audit.26,33,34,35 Successful implementation of guidelines requires an effective dissemination strategy. It is generally agreed that the provision of information alone is ineffective in implementing clinical change and that additional interventions such as educational meetings, outreach clinics, and clinical reminders are required.36

Our guidelines were disseminated by postal distribution. Letters to practitioners following patients' initial consultations also provided advice where referral practice was not ideal. In addition, a lecture was given on the topic as part of the local GDP programme. It would appear that despite these additional measures, uptake of the information provided was poor. A better response may have been elicited by targeting those GDPs who repeatedly referred late, on an individual basis with regards to information dissemination. This approach will be incorporated into the third audit cycle.

Studies have shown that information uptake is improved if those using the guidelines are involved in formulating them.33,34 The lack of any local consensus during the development stage may therefore, have affected our outcome. Consideration of these additional factors may be beneficial in any future research on this matter.

Conclusion

The first audit cycle effectively highlighted deficiencies in the referral practice of local general dental practitioners. Development of referral guidelines might have contributed to the increased referral rate. However, there was no statistically significant improvement in the percentage of patients referred by the recommended age, or in the percentage of patients having interceptive extractions prior to referral. This study is in agreement with other studies that have reported the difficulties of trying to improve referral practice in medicine and dentistry.

References

Bass TB . Observations on the misplaced upper canine tooth. Dent Prac 1967; 18: 25–33.

Moyers RE . Handbook of orthodontics. 4th edn. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers Inc, 1988.

Dachi SF, Howell FV . A survey of 3,874 routine full mouth radiographs. II. A study of impacted teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1961; 14: 1165–1169.

Ericson S, Kurol J . Radiographic assessment of maxillary canine eruption in children with clinical signs of eruption disturbance. Eur J Orthod 1986; 8: 133–140.

Bishara SE . Impacted maxillary canines: A review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1992; 101: 159–171.

Hitchin AD . The impacted maxillary canine. Br Dent J 1956; 100: 1–14.

Ericson S, Kurol J . Radiographic examination of ectopically erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1987; 91: 483–492.

Kettle MA . Treatment of the unerupted maxillary canine. Dent Prac 1957; 8: 245–255.

Becker A, Smith P, Behair R . The incidence of anomalous maxillary lateral incisors in relation to palatally displaced canines. Angle Orthod 1981; 51: 24–29.

Becker A, Zilberman Y, Boarz T . Root length of lateral incisors adjacent to palatally displaced canines. Angle Orthod 1984; 54: 218–224.

Brin I, Becker A, Shalhav M . Position of maxillary permanent canine in relation to anomalous or missing incisors: A population study. Eur J Orthod 1986; 8: 12–16.

Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M . The palatally displaced canine as a dental anomaly of genetic origin. Angle Orthod 1994; 64: 249–256.

Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M . Palatal canine displacement: guidance theory or an anomaly of genetic origin? Sense and nonsense regarding palatal canines. Angle Orthod 1995; 65: 99–102.

Ericson S, Kurol J . Resorption of incisors after ectopic eruption of maxillary canines: A CT study. Angle Orthod 2000; 14: 172–176.

Broadway RT, Gosney MBE . An assessment of the demands made by orthodontic conditions on the oral surgery facilities at one General Hospital in Southern England. Comm Dent Health 1987; 4: 231–238.

Al Nimri K, Richardson A . Applicability of interceptive orthodontics in the community. Br J Orthod 1997; 24: 223–228.

Kohavi D, Becker A, Zilberman Y . Surgical exposure, orthodontic movement, and final tooth position as factors in periodontal breakdown of treated palatally impacted canines. Am J Orthod 1984; 85: 72–77.

Williams BH . Diagnosis and prevention of maxillary cuspid impaction. Angle Orthod 1981; 51: 30–40.

Fearne J, Lee RT . Favourable spontaneous eruption of severely displaced maxillary canines with associated follicular disturbance. Br J Orthod 1988; 15: 93–98.

Jacobs SG . Reducing the incidence of palatally displaced canines by extraction of deciduous canines. The history and application of this procedure with some case reports. Aust Dent J 1998; 43: 20–27.

Shapira Y, Kuftinec MN . Early diagnosis and interception of potential maxillary canine impaction. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 1450–1454.

Brown NL, Sandy JR . Spontaneous improvement in position of canines from apparently hopeless positions. Int J Paediatr Dent 2001; 11: 64–68.

Ericson S, Kurol J . Early treatment of palatally erupting maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canine. Eur J Orthod 1988; 10: 283–295.

Power SM, Short MBE . An investigation into the response of palatally displaced canines to the removal of deciduous canines and an assessment of factors contributing to favourable eruption. Br J Orthod 1993; 20: 215–223.

Bruks A, Lennartsson B . The palatally displaced maxillary canine. A retrospective comparison between an interceptive and a corrective treatment group. Swed Dent J 1999; 23: 149–161.

O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F et al. The effect of orthodontic referral guidelines: a randomised clinical trial. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 392–397.

Emslie CJ, Grimshaw J, Templeton A . Do clinical guidelines improve general practice management and referral of infertile couples? Br Med J 1993; 306: 1728–1731.

Jones RH, Lydeard S, Dunleavey J . Problems with implementing guidelines: a randomized controlled trial of consensus management of dyspepsia. Qual Health Care 1993; 2: 217–221.

Oakshott P, Kerry SM, Williams JE . Randomized control trial of the effect of the Royal college of Radiologists' guidelines on general practitioners' referrals for radiographic examination. Br J Gen Pract 1994; 44: 197–200.

Kerry S, Oakeshott P, Dundas D, Williams J . Influence of postal distribution of The Royal College of Radiologists' guidelines, together with feedback on radiological referral rates, on X-ray referrals from general practice: a randomized clinical trial. Fam Pract 2000; 17: 46–52.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristofferson DT et al. Audit and Feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database systematic review 2003; 3: CD000259.

Thomson O'Brien M A, Oxman A D, Davies D A et al.Audit and Feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database systematic review 2000; 2: CD000259.

McComb JL, Wright JL, O'Brien KD . Clinical guidelines for dentistry: will they be useful? Br Dent J 1997; 183: 22–26.

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM et al. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. Br Med J 1998; 317: 465–468.

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Implementing clinical guidelines: can guidelines be used to improve clinical practice? Effective Health Care 1994; 1: 1–12.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A et al. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. Br Med J 1999; 318: 527–530.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, T., Nute, S. An audit of referral practice for patients with impacted palatal canines and the impact of referral guidelines. Br Dent J 200, 493–496 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813524

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813524

This article is cited by

-

Are patients with impacted canines referred too late?

British Dental Journal (2016)

-

Far too late

British Dental Journal (2006)