Key Points

-

A postal survey of orthodontists in the UKsuggests that there is wide agreement regarding both the potential value of PCDs in orthodontic practice and the tasks such workers could perform.

-

There was some concern regarding whether PCDs should perform some clinical orthodontic procedures.

-

Agreement on suitable and unsuitable tasks was not influenced by the age of the practitioner, their date of qualification or the amount and setting of practice that they performed.

-

The supported proposed tasks largely agreed with the draft frameworks for initial PCD education released by the General Dental Council.

Abstract

Objective To determine the opinions of UK orthodontists regarding potential clinical tasks to be carried out by orthodontic professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs).

Design and setting Postal questionnaire survey of orthodontists within the UK.

Subjects and methods A survey was developed including questions about respondents' current and previous posts, followed by seventeen potential tasks to be carried out by PCDs to prescription. Respondents stated whether a suitably trained PCD should perform each task to direct prescription. Respondents could mention additional clinical tasks that they considered appropriate. The questionnaire was posted to members of the British Orthodontic Society who were eligible to be included on the finalised specialist orthodontist register held by the General Dental Council.

Results Five hundred and eighty one (70.6%) of 821 questionnaires were returned. Most procedures were supported but there was less support for four procedures, a majority against the fitting of bonded lingual retainers and respondents were undecided about molar band cementation, direct bonding of brackets and fitting of headgear. Amount or type of clinical practice or the date of qualification did not alter the pattern of responses given.

Conclusions There is support for the introduction of a class of orthodontic PCD and agreement regarding the nature of clinical tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since before the publication of the Nuffield Report of 1993 on the Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry,1 and the more recent General Dental Council Consultation paper Professionals complementary to dentistry: a consultation paper,2 there have been moves to change the pattern of the way that dentistry is practiced within the UK, particularly in the primary care setting. A major component of these changes is the introduction of expanded duties for professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs), previously described as dental auxiliaries.

PCDs were considered as long ago as 1921, when the New Zealand School Dental Service was started. The local government considered that it would be impossible to train the required number of dentists to service the needs of the population and that a PCD would be of help to redress the imbalance, and so dental nurses were trained to perform various tasks.3 Within the UK, pilot programmes commenced by the Royal Air Force were followed in 1949 by a civilian training programme for dental hygienists. The General Dental Council4 instigated a program to train and employ dental PCDs based at New Cross, London. The dental therapist received, over two years, a training similar to the New Zealand PCD, with the exception that whilst the New Zealand group were able to diagnose and carry out their own treatment plans, their UK equivalents worked to the prescription of a dentist. In the 1960s, three experimental programs on expanded duties for dental auxiliaries were completed in the United States and Canada.5,6,7 These early programs were limited in that an auxiliary was restricted to carrying out reversible procedures or those that carried reduced or minimal risk of harming the patient. However by the early 1970s, groups in the United States were showing that auxiliaries could provide high quality treatment compared with dentists when placing amalgam restorations.8

Blau9 assessed the use of auxiliaries in orthodontic practices within the state of Massachusetts. Eighty five percent of orthodontists used auxiliaries to help with oral health education, radiography, minimal adjustments of fixed appliances and cement removal. The orthodontists questioned were keen to use auxiliaries for many more tasks as long as the auxiliary was covered by malpractice insurance. Biannual surveys of orthodontic practices in the United States carried out since 1981 have shown a steady increase in the percentage of many tasks delegated to auxiliaries during the period 1981 to 1987.10

In Europe and the UK, long term planning for provision of orthodontic treatment has tended to concentrate on the number of trainee orthodontists. Until recently, it was considered that despite an increase in demand for orthodontic treatment, a fall in the birth rate in Europe was likely to lead to a static or reduced need to train orthodontists,11,12 although this was questioned by some.13 Stevens et al14 pointed out that with the birth rate dropping and a recent increase in the number of orthodontic trainees, an imbalance had been redressed and felt a reduction in the number of trainees might well be prudent. However, it is now widely considered that within the UK there is a chronic shortage of orthodontists available to treat the population,15 leading to a proposal to introduce orthodontic auxiliaries into the UK. It is now estimated that 50% of 11-year-old children require some form of orthodontic treatment.16 Whilst only half of this total may require treatment from a specialist, this still leaves a very poor orthodontist to patient ratio. Moss17 showed that the UK has fewer orthodontic specialists per 100,000 of population than any northern European country other than Eire.

An alternative option, employed elsewhere in Europe,17,18 would be the use of auxiliary personnel during a course of orthodontic treatment. Reports indicate that the use of auxiliaries can help to raise treatment standards, as well as enhancing productivity and efficiency.19,20,21,22 This would be accompanied by a reduction in training costs compared with orthodontists and the possibility of focusing PCD personnel in areas of the country most in need of orthodontic provision.

In the UK, dental hygienists and dental therapists are currently licensed by the GDC to carry out a variety of intra-oral procedures under direct prescription of a dentist. It would only require an amendment of GDC regulations to allow hygienists and therapists to carry out a variety of orthodontic tasks. Although the use of dental nurses as orthodontic auxiliaries may be attractive to many orthodontists, a change in governmental legislation would be required to allow extended intra-oral procedures to be carried out. The Dental Auxiliaries Review Group (DARG) of the GDC supported the introduction of appropriately trained dental hygienists and dental therapists to assist in the treatment of patients undergoing orthodontic treatment.2

Several groups have prepared for a possible change in regulations that will allow the use of orthodontic PCDs by preparing training courses.23,24,25 In order to assess how such auxiliaries are likely to be used once trained, we decided to carry out a poll of those orthodontists most likely to be in a position to use PCDs.

Methods

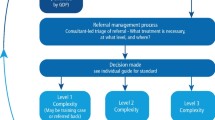

Questionnaires were developed and piloted with full- and part-time professional members of staff within the Dental Institute. The list of respondents was developed from all members of the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) who were eligible to be included on the finalised specialist orthodontist list held by the General Dental Council. This population was then subdivided into four groups, namely consultant orthodontists and training grades, specialist practitioners, community orthodontists and those working as clinical assistants.

The questionnaire was posted with a covering letter explaining the rationale for the study. A series of questions related to the practitioner's current post and previous training were followed by a list of 17 potential tasks. The respondent was requested to state whether or not they would be happy for a suitably trained PCD to perform each task to direct prescription, or whether they were undecided regarding the task. This was followed by a free space in which respondents could mention any other potential clinical tasks that they considered appropriate for PCDs. The questionnaire was designed to be relatively brief in order to encourage a maximum return. The questionnaire was accompanied by a stamped addressed envelope. Data from replies were coded and analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Unix, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Differences in responses between groups of respondents in terms of type of employment, date of receiving an orthodontic qualification, amount and type of clinical practice carried out and amount of NHS compared with private treatment carried out were compared using chi-squared, Mann-Whitney U and logistic regression analysis.

Results and Discussion

A total of 821 questionnaires were dispatched. A total of 581 responses were returned, a response rate of 70.6%. The overall results are presented in Table 1.

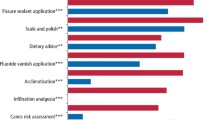

The data are hereafter displayed graphically for simplicity. Figure 1 shows the responses from the consultant group, which included hospital academics, senior registrars and specialist registrars. Figure 2 displays the results from the specialist practitioner group, Figure 3 gives the results from the community orthodontists group and Figure 4 refers to those employed as clinical assistants.

Of the 17 different prescriptive procedures which orthodontists were questioned about, the following procedures were strongly supported (greater than 75% in favour).

-

1

Impression taking.

-

2

Intra-oral radiographs.

-

3

Extra-oral radiographs.

-

4

Clinical photography.

-

5

Separator fit.

-

6

Elastomeric or ligature change.

-

7

Oral hygiene instruction.

-

8

Topical fluoride application.

-

9

Cement removal.

Four procedures were favoured, but not as strongly, with 66% in favour of occlusal records, 65% in favour of archwire changes, 59% in favour of fitting removable retainers and 57% in favour of PCDs carrying out debonding procedures.

Only one procedure was definitely not supported by orthodontists, namely placement and cementing of bonded lingual retainers, where only 19.3% were in favour and 65% were against.

There was considerable controversy regarding three procedures, for which approximately 40% were in favour, 40% against and 15%–20% undecided. These were:

-

1

Fitting, and cementation of molar bands. Many respondents however were keen to select, and/or fit the bands prior to cementation by the PCD.

-

2

Direct bonding of brackets

-

3

Fitting of headgear

Differences in responses between groups of respondents in terms of type of employment, date of receiving an orthodontic qualification, amount and type of clinical practice carried out and amount of NHS compared with private treatment carried out were compared using chi squared, Mann-Whitney U and logistic regression analysis. Results indicated that there were no significant differences between groups for the proposed procedures that PCDs should or should not carry out within orthodontic practice. There was no relationship between the amount or type of clinical practice carried out, or the date of qualification, and the pattern of responses recorded by those returning the questionnaire.

Respondents were also able to make comments regarding possible further functions of a PCD. A large number thought that PCDs would be of great benefit for counselling patients regarding their orthodontic treatment and appliances. It is clear that the proposed tasks for orthodontic PCDs (recently renamed as orthodontic therapists) as proposed by the General Dental Council's Draft framework for the initial education of PCDs24 include all of the approved tasks listed above, together with several others.

This study was limited to opinions on the tasks to be performed by orthodontic PCDs. However there are a number of other important and potentially controversial issues associated with the training of and clinical service delivered by such PCDs. We partially addressed two of these issues in our covering letter to the questionnaire respondents. They were told to assume that the PCD in question would be practicing under the supervision of those who were recognised Specialists in Orthodontics, and hence the range of tasks approved may have been influenced by this assumption. There is considerable concern amongst some specialist orthodontists regarding not only the supervision but also the nature, location and duration of training programmes for orthodontic PCDs. The respondents were also implicitly led to assume that any such training was to be carried out under the auspices of a recognised educational establishment, since they were informed that the questionnaire was designed to inform curriculum design for PCD training. Again this may have influenced the willingness of some orthodontists to approve certain tasks. There is limited data available on the potential of PCDs to address regional inequalities in the provision of care and on the potential for economic exploitation of such workers, but this study did not set out to address these issues. Such factors may need to be considered in assessing manpower needs and in planning future training.

Conclusions

The results show that orthodontists in the UK are very much in favour of PCDs carrying out a wide variety of prescribed procedures. Of the procedures considered, only fitting of bonded retainers is strongly opposed. However, opinion regarding band placement, bonding and fitting of headgear was more contentious. The 'comments' section of the questionnaire indicated that many operators felt that when placing direct bonds and bands, the accuracy of placement is of great importance. Recent pilot studies carried out25,26 have shown that with correct training both dental hygienists and dental nurses can position brackets with acceptable accuracy. Further published work on this matter may go some way to encourage orthodontists to change their views regarding these procedures and to support draft educational guidelines proposed by the GDC. When placement and adjustment of headgear was considered, comments revolved around the current debate regarding the safety of headgear wear and the possibility of injury to patients who wear them. It is to be hoped that adequate education of orthodontic therapists will help to alleviate such fears

References

Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry. London: Nuffield Foundation, 1993.

Professionals complementary to dentistry: a consultation paper. London: General Dental Council, 1998.

Fulton JT . Experiment in dental care. Results of New Zealand's use of school dental nurses. Monograph Series No. 4. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1951.

General Dental Council. Information and announcements. School for dental auxiliaries. Br Dent J 1960; 109: 323.

Abramowitz J . Expanded functions for dental assistants: a preliminary study. J Am Dent Assoc 1966; 72: 386–391.

Baird KM, Purdy EC, Protheroe DH . Pilot study on advanced training and employment of auxiliary personnel in the Royal Canadian Dental Corps: final report. J Can Dent Assoc 1963; 29: 778–787.

Ludwig WE, Schnoebelen EO, Knoedler JD . Greater utilisation of dental technicians. II. Report of clinical tests. Presented at 17th National Dental Health Conference, American Dental Association, 1966.

Hammons PE, Jamison HC, Wilson LL . Quality of service provided by dental therapists in an experimental program at the University of Alabama. J Am Dent Assoc 1971; 82: 1060–1066.

Blau MA . Expanded use of auxiliary personnel in orthodontic practice. Am J Orthod 1973; 64: 137–146.

Gottlieb EG, Nelson AH, Vogels DS . JCO orthodontic practice study Part 1 trends. J Clin Orthod 1987; 21: 507–515.

Prahl-Anderson B, van't HofM . Long term planning of orthodontic manpower. Br J Orthod 1981; 8: 47–51.

Robertson NRE, Hoyle BA . Orthodontic treatment — time for a change? Br J Orthod 1982; 10: 154–156.

Houston WJB . Orthodontic Manpower (Editorial). Br J Orthod 1981; 8: 1.

Stevens CD, Orton HS, Usiskin LA . Future manpower requirements for orthodontics undertaken in the general dental service. Br J Orthod 1985 12: 168-175.

O'Brien KD, Shaw WC . Expanded function orthodontic auxiliaries; a proposal for their introduction into the UK. Br J Orthod 1988; 15: 281–286.

O'Brien M . Children's dental health in the United Kingdom. Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, Social Survey Division. London: HMSO, 1993.

Moss JP . Orthodontics in Europe. Eur J Orthod 1992; 15: 393–401.

Allred H . The training and use of dental auxiliary personnel. Public health in Europe, Report 7. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1977.

Shaw WC . Improving British orthodontic services. Br Dent J 1983; 155: 131–135.

Sandler PJ . Orthodontics in West Germany. Br J Orthod 1989; 16: 133–135.

Postlethwaite KM, Stephens CD . Report of a survey conducted by the Consultant Orthodontists Group. The nature and distribution of clinical assistant posts in orthodontics in the United Kingdom in 1987. Br Dent J 1989; 166: 166–170.

Yap WL . Extended duties auxiliaries-an insight into training and practice in America and Canada. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 141–142.

Turner PJ, Pinson RR . Training hygienists for an auxiliary role in orthodontics. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 209–213.

Draft Framework for the Initial Education of Professionals Complementary to Dentistry. London: General Dental Council, 2002. At: http://www.gdc-uk.org/formgdc7.html

Chen MS, Horrocks EN, Evans RD . Video versus lecture: effective alternatives for orthodontic auxiliary training. Br J Orthod 1998; 25: 191–195.

Stevens CD, Keith O, Witt P, Sorfleet M, Edwards G, Sandy JR . Orthodontic auxiliaries-a pilot project. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 181–187.

Acknowledgements

This study was submitted for publication before the tragic and untimely loss of Paul Scanlan. He is sadly missed and remembered with affection and respect.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Mrs C. Leslie and Miss P. Coward.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ide, M., Scanlan, P. The role of professionals complementary to dentistry in orthodontic practice as seen by United Kingdom orthodontists. Br Dent J 194, 677–681 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810282

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810282

This article is cited by

-

How orthodontists see the role of PCDs

British Dental Journal (2003)