Key Points

In Brief

-

The functions of provisional (sometimes termed temporary) restorations

-

Diagnostic uses of provisional restorations

-

Provisional restorations for conventional preparations including: the concept of short, medium, and long-term temporisation; materials; and direct and indirect provisional restorations

-

Provisional restorations for adhesive preparations

-

Problem solving

Key Points

Crowns and extra-coronal restorations:

-

1

Changing patterns and the need for quality

-

2

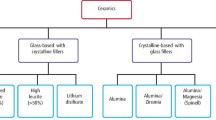

Materials considerations

-

3

Pre-operative assessment

-

4

Endodontic considerations

-

5

Jaw registration and articulator selection

-

6

Aesthetic control

-

7

Cores for teeth with vital pulps

-

8

Preparations for full veneer crowns

-

9

Provisional restorations

-

10

Impression materials and technique

-

11

Try-in and cementation of crowns

-

12

Porcelain veneers

-

13

Resin bonded metal restorations

Abstract

The important role of provisional restorations is often overlooked. This may be because they are left until the end of an appointment when time for construction is short or because they generally do not need to last for long. However, not only can good provisional restorations help produce better final restorations, they can also save a lot of time and expense at subsequent appointments. In fact time spent in their construction will be more than repaid in time saved doing additional procedures, adjustments and remakes later on.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

This article discusses the need for provisional restorations, the types and materials available. Provisional restorations for adhesive restorations often pose a difficult problem and these are considered separately. You may also encounter other difficulties with provisional restorations so we end the article on problem solving.

Functions of provisional restorations

Provisional restorations are used in the interim between tooth preparation and fitting a definitive restoration. The various functions they fulfil are described in Table 1. With crown preparations provisional restorations are generally essential to cover freshly cut dentine and prevent tooth movement. With adhesive preparations protection of exposed dentine is usually less of an issue and often a provisional restoration is not needed, but there are still occasions where it is important to prevent unwanted tooth movement or maintain aesthetics.

Provisional restorations can be invaluable for testing out aesthetic and occlusal changes before they are incorporated in the definitive restoration. They can also help stabilise the periodontal condition prior to definitive restoration. These diagnostic uses will be considered in more detail in the next section.

As well as the prophylactic and diagnostic uses, provisional restorations have other practical applications. For example, callipers may be used to test the thickness of a provisional restoration to ensure sufficient tooth preparation to accommodate the proposed restorative material (Fig. 1). Occasionally, a provisional restoration may be used to provide a coronal build up for isolation purposes during endodontic treatment. A period of long-term provisional restoration may also be advisable to assess teeth of dubious prognosis. Finally, a provisional restoration may find a use as a matrix for core build ups in grossly broken down teeth, simply by removing the coronal surface to allow placement of restorative material.

Diagnostic uses

Provisional restorations, especially those used for conventional preparations, are invaluable in situations where aesthetic, occlusal or periodontal changes to a patient's dentition are planned. The principles behind such changes are discussed later.

Aesthetic changes

Proposed changes to the shape of anterior teeth are best tried out with provisional restorations to ensure patient acceptance, and, approval from friends and family; clearly, it is easier to trim or add acrylic than it is porcelain. Once happy, an alginate is recorded so that the technician can copy the shape into the definitive restoration. If only one or two teeth are involved it is perfectly possible to contour provisional restorations at the chair side. It is however important to balance the time spent doing this against the advantages of having a diagnostic wax up and matrix made in the laboratory (Fig. 2). Alternatively, indirect provisional restorations can be prescribed which will be described later.

Occlusal changes

A patient's tolerance to changes in anterior guidance or increased occlusal vertical dimension is best tried out with provisional restorations. Again, a diagnostic wax up is advisable, and, with occlusal changes, the importance of using casts mounted on a suitable articulator cannot be overstated (Fig. 3). Direct or indirect provisional restorations are then constructed from these and cemented temporarily after adjusting to provide even occlusal contact in the intercuspal position and guidance or disclusion if required. The patient can then be examined at a further appointment and the occlusal surfaces copied as long as the following criteria are met:

-

Restorations are still cemented

-

Occlusal contacts have been maintained, with no drifting of teeth

-

Teeth are not mobile, or existing mobility is not increasing

-

There is no discomfort

Guidance surfaces can be copied between provisional and definitive restorations by using a custom guidance table as described in Part 5 of the series.

Where it is decided to increase the patient's occlusal vertical dimension, provisional restorations provide a way of assessing tolerance to the increase, as well as assessing aesthetics and the overall occlusal scheme. However it is often wise to make an initial assessment of such changes with a more reversible method, such as a splint, before the teeth are prepared.

Periodontal changes

It may be necessary as part of a patient's periodontal treatment to remove overhanging restorations to allow access for cleaning and resolution of inflammation. Long-term wear of properly fitting and contoured provisional restorations allows the health of the gingival margin to improve and its position to stabilise before impressions are recorded for definitive restorations.

Following periodontal or apical surgery the tissues will also need time to stabilise before the final finish line is cut for definitive crowns. Where surgical crown lengthening is used to increase clinical crown height, it is best to allow 6 months before definitive restoration, especially if the aesthetics are critical.1 If provisional restorations are provided soon after crown lengthening it is important to avoid taking the preparations subgingivally as this may set up a chronic gingivitis which is difficult to resolve.

Changes in tooth shape – avoiding problems

For the majority of people, minor adjustments in tooth shape are unlikely to cause any problems, but for others, eg singers and wind instrument musicians, the eventual restorations, if poorly planned, may interfere with the patient's 'embouchure'. This term describes the fine mouth movements and lip/tooth contact required for speech production or sound generation in the case of a musical instrument. Also the incorporation of wider cervical embrasure spaces, to facilitate interproximal cleaning, may occasionally cause embarrassment because of air leakage. Therefore it makes sense to copy the features of successful provisional restorations, to avoid patient dissatisfaction and expensive remakes.

Provisional restorations for conventional preparations

The variety of provisional restorations available can seem bewildering. To help you through the maze we need first to consider the materials and then the techniques by which provisionals can be made. Most provisionals are made directly at the chair side, but for long term wear or diagnostic use there can be advantages in having them laboratory-made.

It is worth emphasising that the length of time between preparation of teeth and cementation of final restorations can vary from a few days for straightforward cases (shortterm), to several weeks (medium-term) or even, in the case of complex reconstruction, several months (long-term). The longer provisional restorations are in the mouth, the greater are the demands on the material from which they are made.

Materials

Materials used in the surgery comprise pre-formed crowns (made of plastic or metal), self cured or light cured resins or resin composites and cements. Laboratory formed temporaries are generally made in self cured or heat cured acrylic, or cast metal.

Pre-formed crowns

Also known as proprietary shells, these come in a series of sizes but usually need considerable adjustment marginally, proximally and occlusally. Plastic shells are made from polycarbonate or acrylic, and, with good aesthetics, are commonly used for anterior teeth including premolars. Metal shells may be made from aluminium, stainless steel or nickel chromium and are only used on posterior teeth. Both plastic and metal shells can be relined with self cured resin to improve their fit.

Self or light cured resins

A variety of materials is available for either direct or indirect techniques:

-

Polymethyl methacrylate (self or heat cured) (eg Vita K&B Acrylics)

-

Polyethyl methacrylate (eg Snap, Trim)

-

Bis acryl composite (eg Protemp, Quicktemp)

-

Urethane dimethacrylate (light cured) (eg Provipont DC)

-

Restorative composite

Polymethyl methacrylate is strong, has a high wear resistance, is easy to add to, and has good aesthetics, which is maintained over longer periods.2 However, it does have three main disadvantages:

i) Polymerisation shrinkage which can affect fit

ii) Polymerisation exotherm which can damage pulp3

iii) Free monomer may cause pulp and gingival damage

It is, however, a good material for indirect provisional restorations. Self cured acrylic can be polymerised under pressure in a hydroflask which effectively reduces porosity.4 Alternatively, heat cured acrylic can be used.

Polyethyl methacrylate (Fig. 4a) is suitable for intra-oral use as it shrinks less and is less exothermic than polymethyl methacrylate. However, strength, wear resistance, aesthetics and colour stability are not as good. Some presentations come with a good colour range (eg Trim II) while others have only light and dark shades (eg Trim).

Bis-acryl composites (Fig. 4b) produce less heat and shrinkage during polymerisation than other resins, resulting in a better marginal fit.5 Despite being reasonably strong they are brittle in thin section and difficult to add to. Aesthetically they are reasonable, but few shades are available and they stain easily if the unpolymerised surface layer is not removed which may be accomplished with alcohol and polishing. They are more colour stable than polyethyl methacrylate materials and are therefore better suited for use as long-term provisionals.6

Most recently, visible light cured resins have been introduced based on urethane dimethacrylate eg Provipont D.C. These relatively expensive resins have good mechanical properties and, being light cured, the operator has some control over the material's working time. Generally more shades are available than bis acryl composite and the colour is relatively stable, but is still prone to staining. Marginal fit can be poor, but the material can be added to. Light cured materials, especially unfilled ones, have a higher exotherm than chemically cured materials because of their greater speed of reaction.7 This exotherm may have implications for pulpal health.

Restorative composites, normally used for filling teeth, can be used as a provisional material for adhesive preparations, as described later. Other restorative composites are designed for laboratory fabrication but may be useful for long-term provisional restorations.

Cast metal

Alloys used include nickel chromium, silver and scrap gold. Copings can be cast with external retention beads for acrylic or composite. In less aesthetically critical areas of the mouth, metal may be used on its own. Cast metals are very durable, but rarely used unless provisional restorations have to last a long time.

Provisional cements

Provisional restorations are usually cemented with soft cement. Traditionally, a creamy mix of zinc oxide eugenol was used, but nowadays most dentists prefer proprietary materials such as Temp Bond (Fig. 5). This material comes with a modifier, which is used to soften the cement, as described later in the article, to ease removal of the provisional restoration from more retentive preparations. Temp Bond NE is a non-eugenol cement which may be used for patients with eugenol allergy or where there is concern over the possible plasticising effect of residual eugenol on resin cements and dentine bonding agents. Certainly, surface hardness11 and shear bond strength of resin12 to resin can both be affected by eugenol and it is worth noting that eugenol cements can significantly reduce the bond of resin cements to composite cores.16 However, resin bond strengths to enamel13 and dentine14 are not affected if the eugenol residue is removed with pumice and water before conditioning. Microleakage15 is also unaffected by the use of eugenol.

Occasionally, hard cement is needed to retain a provisional on a short preparation. This is considered later in the 'problem solving' section.

Direct provisional restorations — techniques

Most provisional restorations will be made directly in the mouth. As mentioned earlier it is worth taking time in their construction. As a rule of thumb, the time taken to temporise a tooth should be similar to the time taken to prepare it. This approach ensures sufficient time is devoted to good fit and contour. The techniques available are listed overleaf:

-

Shells (proprietary or custom)

-

Matrices (either formed directly in the mouth or indirectly on a cast)

-

Direct syringing

To avoid confusion with terminology, a shell is incorporated into the provisional restoration whereas a matrix is merely used to form it.

Proprietary shells

Shells can be divided into proprietary and custom made. Proprietary shells made of plastic (Fig. 6) or metal (Fig. 7) are used commonly in practice when only one or perhaps two preparations are involved.

Proprietary plastic shells: A crown with the correct mesio-distal width is chosen and placed on the tooth preparation. The cervical margins are trimmed to give reasonable seating and adaptation. The preparation is then coated with petroleum jelly and the crown, containing a suitable resin eg Trim, is reseated. While the resin is still incompletely set, the proximal excess is removed using a sharp bladed instrument such as a half Hollenback amalgam carver. The crown is then removed and replaced several times to prevent resin setting in undercuts. Finally, the crown is adjusted and polished using steel or tungsten carbide burs and Soflex discs. Diamond burs are best avoided, as they tend to melt the shell and resin because of the heat generated.

Proprietary metal shells: Aluminium crowns are really only suitable for short-term use as they are soft resulting in wear and deformation. Furthermore, they can produce galvanic reactions in association with amalgam restorations. Their fit is usually poor unless considerable time is spent trimming and crimping the margins followed by relining with a resin. Stainless steel or nickel chromium crowns may occasionally be used on molar teeth opposed by flat cusps where heavy occlusal loading would quickly wear or break a resin crown.

Custom shells

Some operators favour custom shells for multiple tooth preparations. The shell is made in advance of tooth preparation so the desired external contours are pre-formed, but relining and careful marginal trimming are necessary prior to fitting. Custom shells are of two types, either beaded acrylic or 'Mill Crowns'. Both offer the advantage of being able to use the superior properties of polymethyl methacrylate, whilst avoiding pulpal damage by constructing the shell out of the mouth.

The beaded acrylic shell is formed within an impression taken of the teeth prior to preparation or of a diagnostic wax up. A thin shell of polymethyl methacrylate is constructed in the impression by alternately placing small amounts of methyl methacrylate monomer followed by polymer, taking care not to make the shell too thick, otherwise it will need time-consuming adjustment later. Once set, it is trimmed and then relined in the mouth as with polycarbonate crowns.

Mill Crowns are formed by first cutting minimal crown preparations on a stone cast. A pre-preparation matrix is then filled with polymethyl methacrylate and placed over the preparations. The trimmed and adjusted provisional crowns are again relined in the mouth.

Matrices

Many operators prefer matrices (Fig. 8) to shell crowns for making single or multiple provisional crowns. This is because matrices closely duplicate the external form of satisfactory existing teeth, or, if changes are required, a diagnostic wax up. If the matrix is carefully seated minimal adjustments are generally needed other than trimming flash at the crown margin.

There are three main types of matrix:

-

Impression (alginate or elastomer)

-

Vacuum formed thermoplastic

-

Proprietary celluloid

The simplest way of making a matrix is to record an impression of the tooth to be prepared either in alginate or silicone putty. Impression matrices are quick, easy and inexpensive, and can be formed while the local anaesthetic is allowed to take effect. When impression matrices are used some judicious internal trimming may be helpful to improve seating and bulk out critical areas of the provisional restoration. These aspects are covered later when we deal with problem solving. Alginate matrices are best at absorbing the resin exotherm3 — although the temporary should have been removed before this stage of set. Elastomeric impression matrices have the advantage of being reusable, allowing them to be disinfected and stored in case they are required again. Polyvinylsiloxane putty impressions are frequently used because of their ease of handling and long-term stability.

If a tooth is broken down or its shape needs to be changed, it will first need to be built up. Soft red wax can be used for this purpose, but anyone who has tried this will know that it does not stick well. Adhesion can be improved dramatically by first painting the tooth with a coat of varnish (eg copal ether or glass ionomer varnish) and allowing it to dry. The opposing teeth are smeared with petroleum jelly to allow their form to be stamped into the wax should it be necessary to build up the occlusal surface. Rather than try and achieve perfection with an intra-oral wax-up it is better to aim for a slight over-contour, which can be corrected by trimming the provisional restoration. It is best to avoid putty for making the matrix as it can distort or displace the wax when the impression is seated.

There is no doubt that the above technique is invaluable, however, when dealing with multiple crowns it is a much better strategy to first carry out a diagnostic wax up on mounted casts (Fig. 3). The intended aesthetics and occlusion can be formed much more efficiently and patients appreciate being able to see a 'blue print' of the definitive restorations on the articulator. Moreover, the wax up can be used to form a suitable indirect matrix.

Indirect matrices can be made from impression material (Fig. 9a) or you can ask your laboratory for a vacuum formed matrix made of clear plastic (Fig. 9b). If you decide to make an indirect matrix from impression material remember to first soak the cast for five minutes. In this way you will avoid the embarrassment of sticking impression to cast. Immersion in warm water (not hot) has the advantage of speeding up the impression material's setting time.

Where aesthetic or occlusal changes are proposed, provisional crowns can be formed in the mouth with laboratory-made matrices: (a) A putty or alginate matrix can be formed directly on the wax-up (remember to soak cast first); and (b) A vacuum formed matrix can also be made, but on a stone duplicate of the wax-up to prevent the wax from melting (matrix shown prior to trimming)

Vacuum formed matrices are made of clear vinyl sheet produced on a stone duplicate of the waxed up cast. This is necessary to avoid melting the wax when the hot thermoplastic material is drawn down. Not everyone is enthusiastic about using a vacuum formed matrix because they are flexible and can distort when seated, especially if there are few or no adjacent teeth to aid location. Where it is necessary to rely on the soft tissues for matrix location we prefer to use an impression matrix.

Whilst vacuum formed matrices are not without problems, being made of clear plastic they are indispensable for moulding light cured resins. A proprietary celluloid matrix can be used if only a single provisional crown is to be formed using light cured resin.

Whatever matrix is chosen care must be taken in its use. After tooth preparation, a thin smear of petroleum jelly is placed over the reduced tooth and adjacent teeth. The matrix is blown dry and the mixed resin is syringed into the deepest part of the appropriate tooth recess, taking care not to trap air, especially at the incisal angles. After reseating, the matrix is left until the resin reaches a rubbery stage. It is then removed and interproximal excess removed in the same way as for the proprietary shell. Setting can be monitored to some extent by testing the consistency of a small portion of material syringed onto the front of the seated impression. Following removal, the crowns are trimmed, polished and cemented.

Direct syringing

When no shell temporary can be found to fit and, for whatever reason, no matrix is available it can be useful to syringe material directly around a preparation. For this purpose the polyethyl methacrylate materials are best as they can be mixed to sufficient viscosity not to slump but are still capable of being syringed. This property whereby a material undergoes an apparent decrease in viscosity at high rates of shear, as when passed through a syringe nozzle, is called 'shear thinning'. It is also seen with the polyether material, Impregum.

When syringing, start at the finish line and spiral the material up the axial walls. Overbuild the contours slightly as it is easier to trim away excess than to have to add later.

Indirect provisionals

Many dentists will not have used indirect provisional restorations and may find it hard to justify laboratory costs. However, indirect provisionals offer certain advantages with complex cases needing long-term temporisation. Firstly, materials which are stronger and more durable can be used eg heat cured acrylic or self cured acrylic cured in a hydroflask. Secondly, if aesthetic or occlusal changes are to be made these can be developed on an articulator. Indirect provisionals can certainly save clinical time, especially with multiple restorations and most particularly where there is to be an increase in vertical dimension, especially where the patient is a bruxist (Fig. 10).

Metal and acrylic provisionals used in the occlusal reconstruction of a bruxist: (a) A relined NiCr shell at tooth LL7 (37) where the previous acrylic provisional crown had fractured repeatedly; and (b) The upper arch has acrylic heat cured onto beaded metal copings in an attempt to improve fracture resistance – however a good bond between metal and acrylic is needed for success

Whether or not major changes are indicated, it is best to decide on the type of provisional restoration during treatment planning. If indirect restorations are chosen, sufficient time can be scheduled either to make them whilst the patient waits or an additional appointment can be made to fit those made in the laboratory.

Some operators favour making indirect provisional restorations from self cured acrylic at the same appointment the teeth are prepared. If the surgery has an on site technician (or suitably trained nurse) this can be a very efficient way of working as it allows the dentist to do something else while the provisional restorations are being made. An alginate impression is recorded of the prepared teeth and this is cast up in quick setting plaster. The plaster model is then coated with cold-mould seal and a suitable shade of self cured acrylic mixed up. The acrylic is then flowed into a matrix made from the diagnostic wax up (eg silicon putty or vacuum formed) which is then seated onto the cast and its position stabilised with elastic bands, taking care not to distort it. Polymerisation takes place within a hydro flask following which the matrix is removed; the relatively soft plaster dug out and the acrylic flash trimmed back to the margin. Additions may need to be made to the margins of the crowns where polymerisation shrinkage has produced a gap. This can be done in the mouth or on a cast. If done in the mouth, then the tooth needs lubricating with petroleum jelly and the crowns removed before excessive heat is generated.

Clearly, an extra appointment will be necessary if indirect provisional restorations are made in an outside laboratory. In the interim direct provisional restorations will also be needed. This approach can be very effective, however, where an increase in vertical dimension is prescribed. A number of strategic teeth can be prepared and interim provisional restorations made directly to conform to the existing occlusion (eg from polyethyl methacrylate or Bis acryl composite). On return, the indirect provisional restorations can be used to establish the increased vertical dimension on multiple teeth. Often these cases require minimal or no occlusal preparation as occlusal clearance is provided by the increase in vertical dimension. When this happens the interim provisional restoration will resemble a tube with no occlusal surface, which is usually acceptable for short periods.

Provisional restoration of adhesive preparations

Provisional restorations for conventional tooth preparations (eg full veneer crowns, 3/4 crowns, and onlays) obtain retention in a similar way to the final restorations ie via cement on preparations with long, minimally tapered axial walls. The lack of conventional retention provided by most adhesive preparations results in temporary cements being ineffective. A number of strategies can be used to deal with this problem, some of which are more appropriate for certain situations than others:

-

No temporary coverage may be necessary eg with veneer preparations involving minimal dentine exposure and not removing intercuspal or proximal contacts. Where space has been created with a Dahl appliance, the appliance can be used in the interim to retain the teeth in position

-

A simple coat of zinc phosphate cement to protect exposed dentine eg in tooth preparations which are not aesthetically critical and where the occlusion is either not involved or the restoration can be returned rapidly from the laboratory and fitted before significant tooth movement occurs

-

Composite resin bonded to a spot etched on the preparation eg veneer preparations which are aesthetically critical or occlusally critical or have sensitive, fresh cut dentine. The provisional restoration is fabricated using either directly placed composite which is time consuming, or composite and a clear vacuum formed matrix made from a preoperative cast. For longer lasting provisionals, acrylic veneers may be made in the laboratory. Limiting the area of bonding facilitates composite removal, but the bonded area must be ground back to tooth substance when the definitive restoration is fitted. If the composite is cut without water spray it is easier to distinguish between the powdery surface of the ground composite and the glassy appearance of the underlying tooth

-

Composite resin bonded to the opposing tooth to maintain occlusal contact and prevent over-eruption (eg shims or veneers where some additional occlusal reduction is required). After the definitive restoration is placed, the opposing composite is removed

-

Conventional provisional restorations cemented with either a non-eugenol temporary cement or a hard cement such as zinc carboxylate. This approach may be used for adhesive restorations having some mechanical retention eg an inlay or resin bonded crown. The choice of cement will depend on how retentive the preparation is.

It is sensible to expect provisionals for adhesive preparations to be effective only in the short term. Certainly, their diagnostic usefulness in testing changes in aesthetics and occlusion is much more limited than with provisional restorations for conventional preparations.

Problem solving

A number of problems are encountered when making provisional restorations. Some of these are discussed below:

Insufficient bulk of material

The axial walls of resin provisionals are often thin which makes them prone to damage during removal from the mouth. This is particularly the case when minimal amounts of tooth are removed eg preparations for gold crowns. To prevent damage, the provisional should be made temporarily wider by relieving the appropriate part of the impression with a large excavator (Fig. 11). The excess resin can be contoured after it has completely set.

Gross occlusal errors, air blows and voids

An impression matrix not being reseated fully often causes gross occlusal errors and may occur for two reasons:

-

Fins of interproximal impression material being displaced and sandwiched between the impression and the occlusal surface – trim away any suspect areas from the inside of the impression with a scalpel or scissors before reseating

-

Hydrostatic pressure built up within the unset resin during reseating of the impression matrix – consider cutting escape vents cut from the crown margin to the periphery of the impression with a large excavator.

Avoid voids by syringing material directly onto preparations. Of course, material is also loaded into the impression, ensuring the tip is always in the resin, to prevent the incorporation of air.

Locking in of provisional restorations

Provisional restorations are often locked in by extruded material engaging the undercuts formed by the proximal surfaces of adjacent teeth. The technique of cutting out a triangular wedge of material from the gingival embrasure space with a half Hollenback instrument has already been mentioned. This must be done while the material is still soft and before any attempt is made to remove the provisional restoration from the preparation. Once removed, any thin flash should be trimmed with a pair of scissors, and the crown reseated a number of times to ensure it does not lock into place when set.

Provisional inlays can be a particular problem because of the difficulty in removing excess resin proximally on posterior teeth. A time saving technique is possible using two light cured resins,8 a soft one for the cavity floor and base of the box (eg Fermit), and a harder one for the occlusal surface (eg Provipont DC). A vacuum formed, transparent matrix is also needed. The softer resin is condensed into the cavity using a conventional matrix band to limit proximal extrusion. The cavity is filled to the level of the proximal contacts after which the resin surface is pock marked with a condensing instrument to provide mechanical retention for the harder resin. Following light curing the matrix band is removed. The coronal portion of the restoration is formed from the harder resin by means of the vacuum formed matrix. After light curing, the matrix is removed along with the provisional restoration, which can be further cured from the fitting surface. The amount of flash produced by this method is minimal, and the manufacturing of the inlay up to the point of trimming can be completed in less than 4 minutes.8

Marginal discrepancies

Although polymerisation shrinkage can cause marginal discrepancies, it is our opinion that most problems are caused simply by distortion of the margin when the provisional crown is first removed from its preparation. Such distortion results from excess material engaging proximal undercuts and can easily be prevented by following the advice in the previous section.

Should a marginal discrepancy occur with a provisional resin crown, the simplest solution is to reline it. A useful tip is to flare out the inside of the crown margin with a bur. This approach provides a greater bulk of reline material and more area for it to bond. To facilitate seating it is best not to fill the whole crown with resin, but to confine the reline material to the inner aspect of the crown margin, thus reducing hydrostatic pressure.

Multiple crowns

When several adjacent preparations require provisional restorations, reseating an impression containing resin invariably results in all the restorations being joined together as material passes through the thin and often torn interproximal area. Splinting teeth together in this way has the advantage of preventing drift due to poor interproximal and occlusal contacts. However, it is extremely important to ensure the gingival embrasures are opened sufficiently to give good access to tooth brushing (Fig. 12a–c). This is best accomplished with a flame shaped bur (Fig. 12d).

Provisional restorations and gingival embrasures: (a) No gingival embrasure space provided between the maxillary incisors; (b) Bleeding from the resulting gingival inflammation prevented impressions being recorded; and (c) Patients maintain gingival health best where there are open gingival embrasures (as shown in this provisional bridge) to allow toothbrush penetration interproximally; and (d) Gingival embrasures under linked provisionals need to be opened out with a flame shaped bur

Ideally, provisional crowns should be separate, but separation can result in unwanted gaps between them. One way9 of overcoming this is to place small pieces of celluloid strip, roughly 1cm long, between the teeth to be prepared. The strips should have holes punched in their buccal and lingual portions with a rubber dam punch to aid retention in the over-impression. A small amount of alginate is smeared over the celluloid strip's retentive holes before seating the tray. When the impression is removed, the strips stay embedded in the alginate and separate the resin crowns while they are made.

Premature decementation

Premature loss of provisional restorations is frustrating for both patient and dentist. This problem can be largely avoided by ensuring harmony with the occlusion. A few seconds spent marking up and adjusting occlusal contacts will save time in the long run.

Occasionally, it is necessary to use a stronger cement, such as zinc polycarboxylate, especially where retention is limited.

Partial denture abutments

A provisional crown used as a partial denture abutment is made best from an acrylic resin (eg Trim) as additions are easy to make. The following technique is recommended: The provisional crown should initially be kept clear from where rest seats and guide planes are to contact. Fresh resin is then placed in these areas before reseating the partial denture with its components lubricated with petroleum jelly. After the resin has set, the denture is removed and the crown is finished.

Eugenol containing temporary cements and adhesion

As discussed previously, eugenol-containing cements should be avoided where it is intended to cement the definitive restoration to an underlying composite core.

Removing temporary crowns

Although it is desirable for provisional crowns to remain cemented during function, they should still be easily removed when impressions are taken, adjustments are needed, or definitive restorations need cementing. When preparations are of optimal height and taper, the use of even comparatively weak temporary cements may make removal difficult, especially when the provisional restoration needs to remain undamaged for recementation or when definitive crowns are cemented on a temporary basis.

To make removal easier, the cement should be applied in a ring around the inner aspect of the margin. Alternatively, the manufacturer's modifier should be added to the cement (Fig. 5). Equal lengths of base and catalyst with a third of a length of modifier will soften the cement appreciably. Therefore, the proportion of modifier needs to be gauged for each case. Either finger pressure or instruments such as towel clips can then remove the restorations, without risking damage to the preparation margin.

Removal of excess cement

Temporary cement removal is facilitated by pre-applying petroleum jelly to the outside of the restorations and placing floss under each connector of linked crowns before seating (look at Fig. 13). Once set, the excess cement is easily removed with the strategically positioned floss.

Conclusion

Quality restorative dentistry needs quality provisional restorations for predictable results. Dentists therefore need to be familiar with the range of materials and techniques for short term, medium-term and long-term temporisation. Forethought and planning are also needed to ensure the most appropriate provisional is used, especially when multiple teeth are to be prepared or where occlusal or aesthetic changes are envisaged. Such changes are best tried out with provisionals so that modifications can easily be made intra-orally and when satisfactory copied into the definitive restorations. In this respect an initial diagnostic wax-up is invaluable to facilitate the construction of laboratory formed provisionals or matrices.

References

Wise MD Stability of gingival crest after surgery and before anterior crown lengthening. Br Dent J 1985; 53: 20–23.

Crispin BJ, Caputo AA Color stability of temporary restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 1979; 42: 27–33.

Moulding MB, Teplitsky PE Intrapulpal temperature during direct fabrication of provisional restorations. Int J Prosthodont 1990; 3: 299–304.

Donovan TE, Hurst RG, Campagni WV Physical properties of acrylic resin polymerized by four different techniques. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 54: 522–524.

Tjan AH, Castelnuovo J, Shiotsu G Marginal fidelity of crowns fabricated from six proprietary provisional materials. J Prosthet Dent 1997; 77: 482–485.

Lang R, Rosentritt M, Leibrock A, Behr M, Handel G Colour stability of provisional crown and bridge restoration materials. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 468–471.

Gulati AJ Physical properties of provisional restorative materials [MSc]. University of Newcastle Upon Tyne 1996.

Nicholson JW, Chan DC Two-step provisional technique for onlay preparations. J Esthetic Dent 1992; 4: 202–207.

Liebenberg WH Improving interproximal access in direct provisional acrylic resin restorations. Quintessence Int 1994; 25: 697–703.

Shillingburg HT, Hobo S, Whitsett LD Provisional Restorations. Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics. 4 ed pp225–256 Chicago: Quintessence international 1998.

Civjan S, Huget EF, De Simon L B Compatibility of resin composites with varnishes, liners and bases. J Dent Res (Special issue) (Abstract no.27) 1973; 52.

Dilts WE, Miller RC, Miranda FJ, Duncanson MG J Effect of zinc oxide -eugenol on shear bond strength of selected core/cement combinations. J Prosthet Dent 1986; 55: 206–208.

Schwartz RS, Davis RD, Mayhew RW The effect of a ZOE temporary cement on the bond strength of a resin luting agent. Am J Dent 1990; 3: 28–31.

Schwartz R, Davis R, Hilton TJ Effect of temporary cements on the bond strength of a resin cement. Am J Dent 1992; 5: 147–150.

Woody TL, Davis RD The effect of eugenol-containing and eugenol-free temporary cements on microleakage in resin bonded restorations. Operative Dent 1992; 17: 175–180.

Millstein PL, Nathanson D Effects of temporary cementation on permanent cement retention to composite resin cores. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 67: 856–859.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wassell, R., St. George, G., Ingledew, R. et al. Crowns and other extra-coronal restorations: Provisional restorations. Br Dent J 192, 619–630 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801443

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801443

This article is cited by

-

Heat generated during dental treatments affecting intrapulpal temperature: a review

Clinical Oral Investigations (2023)

-

The Effect of Glass and Polyethylene Fiber Reinforcement on Flexural Strength of Provisional Restorative Resins: An In Vitro Study

The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society (2013)

-

Risk management in clinical practice. Part 3. Crowns and bridges

British Dental Journal (2010)