On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

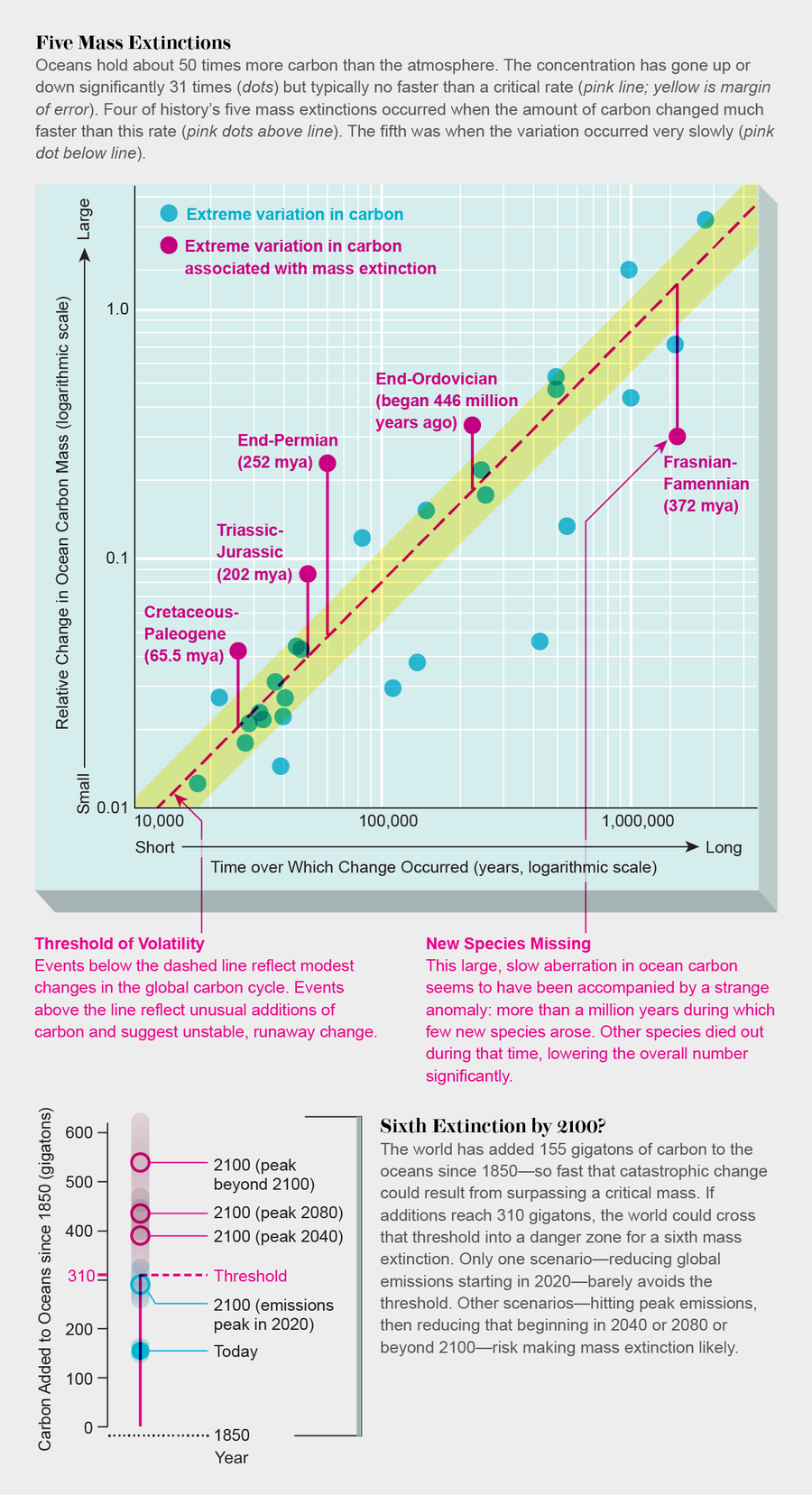

The amount of carbon in our planet's oceans has varied slowly over the ages. But 31 times in the past 542 million years the carbon level has deviated either much more than normal or much faster than usual (dots in main graph). Each of the five great mass extinctions occurred during the same time as the most extreme carbon events (pink dots). In each case, more than 75 percent of marine animal species vanished. Earth may enter a similar danger zone soon. In 1850 the modern oceans contained about 38,000 gigatons of carbon, and a new study by geophysics professor Daniel H. Rothman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology indicates that if 310 gigatons or more are added, the deviation will again become acute. Humans have already contributed about 155 gigatons since then, and the world is on course to reach 400 gigatons by 2100 (small graph). Does that raise the chance for a mass extinction? “Yes, by a lot,” Rothman says.

Credit: Jen Christiansen; Source: “Thresholds of Catastrophe in the Earth System,” by Daniel H. Rothman, in Science Advances, Vol. 3, No. 9, Article No. E1700906; September 20, 2017