Abstract

Aquatic foods are critical for food and nutrition security in Malawi, but it is unclear which populations benefit from different aquatic foods and what factors shape food access. Spatial analysis of food flows across value chains from Lake Malawi to domestic consumers shows that usipa (Engraulicypris sardella) reaches more consumers than chambo (Oreochromis karongae) across all Malawi districts, particularly rural populations. Higher number of markets, nutrient content, and overall supply coupled with lower retail prices and volumes make usipa more accessible to consumers than chambo. Spatial analysis of food flows can guide policymakers towards supporting fisheries that reach vulnerable populations and designing interventions that enhance physical and economic access to fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

One of the biggest barriers to developing nutrition-sensitive aquatic food systems policy is understanding variation in access to nutritious foods for specific populations in specific places. Most data on the distribution of aquatic foods focuses on international trade, but most aquatic food, including in Malawi, is sold in domestic markets. Georeferenced national household surveys sometimes indicate the locations of households that consume fish and whether it was purchased or self-produced; however, the data are often reported in coarse aggregate categories, such as dried or fresh fish, and do not indicate species or origin (domestic or imported, wild caught or aquaculture). At the subnational level, there is typically no systematic understanding of where aquatic foods are transported and sold, and to whom.

A spatial analysis of food access can show how aquatic foods flow from points of production to points of consumption, the implications of those flows for human nutrition and the factors shaping them. Therefore, we tracked flows of fish from three main beach landing sites on Lake Malawi through to retail markets throughout the country using georeferenced surveys with traders (n = 846) at 79 markets. We chose usipa (Engraulicypris sardella), a small sardine-like pelagic fish, and chambo (Orechromis spp.), medium-sized tilapia species, as illustrative species. We predicted they would have distinct spatial footprints of food access, as usipa constitutes the majority of fish caught in the country by volume and value, is relatively affordable and is often sundried and consumed whole, and chambo fetches the highest market price among common Malawian fish species and is often consumed fresh.

Usipa value chains associated with the three beach landing sites (indicated by stars in Fig. 1) move fish to 72 markets, whereas chambo value chains flow to only 16 markets from the same three beach landing sites (including the country’s main chambo landing site). The markets include supermarkets, large urban markets, small rural markets, temporary rural markets, roadside stands and door-to-door vendors (Supplementary Fig. 1). Almost 23% of the Malawian population lives within 5 km of one of the 72 markets where usipa is sold and about 18% of the population lives within 5 km of one of the 16 markets where chambo is sold (Table 1).

Chambo (left) is distributed in lesser volumes and reaches fewer districts, markets (particularly rural markets) and consumers than usipa (right).

About 81% of markets where chambo is sold are urban. By contrast, only 40% of the markets where usipa is sold are urban, revealing that usipa is more accessible to rural populations. The more urban nature of chambo retail can explain why the population within 5 km of chambo markets is only 20% lower than usipa, despite there being 350% more usipa markets. The sale of chambo is concentrated mostly in the central region of the country, in particular Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe, whereas usipa markets are distributed throughout all regions. Large amounts of usipa move from the lakeside to major wholesale markets, including the three largest (Mzuzu, Lilongwe and Blantyre), and are subsequently distributed to retail markets, whilst chambo appears to have more direct-to-retail routes. About 80% of chambo is sold fresh, with the remainder smoked (mostly in the South). About 70% of usipa is sundried and most of the remainder is parboiled. Only 3% is sold fresh or smoked. Processing form, price and overall supply are among probable drivers of post-harvest distribution dynamics.

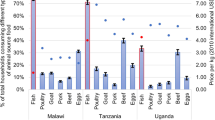

Only 14% of households within 5 km of an usipa market earn at least US$1.35 per person per day in purchasing power parity terms, the average cost of a nutritious diet1, while 18% of households within 5 km of a chambo market earn at least that amount (Table 1). The average price per gram of usipa is about half that of chambo (US$2.76 per kg and US$4.93 per kg, respectively). Usipa is also sold in smaller volumes; the smallest retail volume of chambo (one small fish, 359 g, at US$1.81) is more than six times the price for the smallest retail unit of usipa (one small mound, 102 g, at US$0.29). Economic access to nutrients from usipa is higher than chambo given variation in nutrient content and processing form. For example, there are 27.1 g of protein in a 100 g edible portion of dried usipa compared to between 10.7 and 17.6 g of protein in a 100 g edible portion of fresh chambo, depending on the species and data source2. The ranges of price per nutrient for all nutrients are higher for chambo, except iron, for which the ranges for price per nutrient overlap (Supplementary Table 1). The average selling price of usipa is US$3.12 per kg in the southern region and US$3.14 per kg in the central region but is 22% lower in the northern region (US$2.45 per kg). Prices for chambo are also highest in the central region (US$4.69 per kg), remaining relatively high in the northern region and being lowest in the southern region (US$4.34 per kg and US$3.28 per kg, respectively).

There are potential food and nutrition security benefits for female fish traders and their household members3—and women comprise 51% of total participation in the post-harvest fisheries sector in Malawi4. While many global analyses of aquatic food systems focus on marine fisheries, we provide a case study of inland fisheries, which are particularly important for the nutrition of lactating mothers, infants and young children in sub-Saharan Africa and Malawi5,6. Although 49% of usipa traders in our study markets were female, they are not evenly distributed across space. Of all usipa traders in the northern region, 61% are female, compared to only 30% and 46% of traders in the central and southern regions, respectively. Only 22% of chambo traders are female (Supplementary Table 2).

Our spatial analysis can be overlaid on existing data on food security, nutrition, income and other demographic variables to inform the scaling of nutritional programmes involving aquatic foods. In Malawi, chambo has cultural, economic and nutritional importance, but our spatial analysis suggests that usipa reaches more people across all areas. Although chambo has received more policy and investment focus for fisheries management and development, a focus on usipa fishery and related post-harvest sectors may be beneficial for food and nutrition security across all regions, particularly in rural areas.

Our observations at fish markets, interviews with fish traders and discussions with the government, academics, NGOs and fishery stakeholders at a workshop in Malawi in May 2022 revealed structural and institutional factors that shape fish flows, in addition to supply and demand. For example, lack of timely information on prices at different markets, limited storage and cold chain infrastructure, high transport costs, low access to capital, competition with foreign buyers and male-dominated institutions governing access to space in urban markets all influence traders’ decisions about where and when to sell their fish. Spatially targeted investments in transport and market infrastructure along specific routes and in markets, enhancing access to market information, and building organizational and financial capacity among fish traders could increase access to fish for consumers in specific places while enhancing the efficiency of value chains, reducing food loss and waste, and improving food safety.

Spatial analyses can inform ongoing policy actions in Malawi. These include nutritional education endeavours in fishing communities to increase fish consumption (especially among lactating women and children under five), data collection for the Department of Fisheries’ first-ever census of fish traders and the National Agricultural Investment Plan, which identifies joint responsibilities for Ministries of Agriculture, Health and Population, and Gender, among others, on the implementation of activities ranging from extension services, infrastructure development, nutritional education, private sector support and trade agreements. Information and communication technologies have the potential to generate spatially explicit product and price information while providing value for fish traders. Governing bodies could also reach nutritionally vulnerable communities located far from Lake Malawi and invest in access to fish (for example, via school feeding programmes) to increase demand in low-access locations.

Malawian cross-border dried fish trade is particularly high7. Therefore, subnational spatial analysis of food access complements efforts to track international and cross-border trade (for example, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network8). Our approach could be scaled to encompass broader geographic regions and other food commodities, creating a more comprehensive picture of food access. More broadly, a robust evidence base on spatial variation and drivers of food access can support integrated food system policy and enable governments to respond to calls to better integrate fisheries and aquaculture with agriculture, health and nutrition policy.

Methods

To identify as many fish markets in the country as possible, a team of enumerators began at three primary fish landing sites (in the southern, central and northern regions of Lake Malawi), then traced transactions through the entire value chain until they reached retail-only markets or the country border. At each market (n = 79; Supplementary Fig. 1), surveys with fish traders (n = 846) collected product form, volume, price data, sex of trader and the location the fish was purchased9.

To map the routes and quantities of fish flowing from where value chain actors reported purchasing their fish to where actors reported selling their fish, survey data was used from fisher, wholesaler and retailer value chain nodes. The quantity of usipa and chambo was converted from local non-standard units into grams and summed by unique trade route (buying market/beach to selling market).

The survey data was analysed in Esri ArcPro 2.8.0 using the Closest Facility tool within the network analyst extension. The road network dataset for Malawi, obtained from the World Food Program GeoNode, was imported as a network dataset. In the Closest Facility tool, selling markets were imported as ‘facilities’ and buying markets/beaches were imported as ‘incidents’ with the direction selected as ‘towards facilities’. The travel mode, or distance cost units, were set to kilometres. The output geometry linear shape type was set to ‘along network’. The routes polygon was exported as a new shapefile and joined with the survey data using route (‘Name of Buying Market/Beach’ – ‘Name of Selling Market’) as the join key. The routes shapefile was assigned a graduated symbology with the display field set to the sum of fish (in grams) transported per route. Wholesale routes, which originate at beach sites, were marked in grey; retail routes, which originate at markets, were marked in red.

We used the most recent Integrated Household Survey (IHS5), implemented from April 2019 to April 2020, which received financial support from the Government of Malawi and technical assistance from the World Bank10. Latitude and longitude of surveyed households came from the household geovariables module; annual household income was found in the household income type module; and household size, that is, the number of people that reside in each household, was obtained from the household identification module. All variables of interest were joined into one collated file using the unique household identifier as the join key.

The latitude and longitude of IHS5 Malawian households were displayed in Esri ArcPro as XY coordinates. To estimate the total number of Malawian households within 5 km of a fish market, we used the Buffer Analysis tool to create a 5 km11 buffer layer around each fish market from our market survey data and dissolved it into a single feature class. Then, using ‘select by location’, IHS5 households located within the market buffer zone were exported into a new shapefile. Using the ‘select by attribute’ tool on the newly exported shapefile of households within 5 km, only those with an annual household income greater than the calculated household economic threshold for a nutrient-adequate diet (see supplemental materials) were selected and exported into the final shapefile1. The weight adjustment factors (see p. 46 of ref. 10) were applied to translate the results from the household level out to the population level.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The fish trade dataset is publicly available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21300873.v2. Malawi’s Fifth Integrated Household Survey 2019–2020 data is publicly available from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3818. GIS country boundaries, regional boundaries and the road network layer are publicly available from the Malawi Spatial Data Platform at http://masdap.mw/.

References

Bai, Y., Alemu, R., Block, S., Headly, D. & Masters, W. Cost and affordability of nutritious diets at retail prices: evidence from 177 countries. Food Policy 99, 101983 (2021).

MAFOODS. Malawian Food Composition Table 1st edn (eds van Graan, A. et al.) (South African Medical Research Council, Biostatistics Unit - SAFOODS, 2019).

Kawarazuka, N. & Béné, C. Linking small-scale fisheries and aquaculture to household nutritional security: an overview. Food Security 2, 343–357 (2010).

de Graaf, G. & Garibaldi, L. The value of African fisheries. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture, Circular No. 1093 (2014).

O’Meara, L. et al. Inland fisheries critical for the diet quality of young children in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Food Security 28, 100483 (2021).

Jimenez, E. Y. et al. Breast milk from women living near Lake Malawi is high in docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 95, 71–78 (2015).

Mussa, H. et al. Assessment of informal cross-border fish trade in the southern Africa region: a case of Malawi and Zambia. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 7, 358–366 (2017).

Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Data Center. Price and Cross-Border Trade: East and Southern Africa Cross-Border Trade (accessed 26 September 2022); https://fews.net/fews-data/337

Bennett, A. Fish buying and selling locations, volumes, and trader gender in Malawi. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21300873.v2 (2022).

Fifth Integrated Household Survey 2019–2020 Malawi. MWI_2019_IHS-V_v05_M (National Statistical Office, 2021).

Katungi, E., Horna, D., Gebeyehu, S. & Sperling, L. Market access, intensification and productivity of common bean in Ethiopia: a microeconomic analysis. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 6, 476–487 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Soko, M. Mapunda, H. Chiume, S. Mwentumba, W. Msiska, Y. Nyambose, R. Mapunda, V. Kalua, D. Mughogho, S. Nyirenda and F. Juwani for their work as enumerators during field data collection. This study was supported by a grant from the Michigan State University Alliance for African Partnership (to A.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B., P.M., D.M.I. and J.V. conceptualized and designed the study. P.M. conducted the data collection. A.B., L.S.O.L.-T., B.B. and D.M.I. obtained funding. E.R. led the data analysis, with support from D.M.I., J.R. and A.B. All the authors interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, read the final manuscript and approved its submission. A.B., E.G., E.R., E.K., S.K. and L.S.O.L-T. disseminated results to stakeholders.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Molly Brown, Kendra Byrd, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Source data

Source Data For Fig. 1

Selling market and coordinates, buying market and coordinates, transaction volumes, sex of fish trader, processing form and price data for fish trade transactions of usipa and chambo by fishers, wholesalers and retailers at 79 markets and 3 landing sites.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, A., Rice, E., Muhonda, P. et al. Spatial analysis of aquatic food access can inform nutrition-sensitive policy. Nat Food 3, 1010–1013 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00642-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00642-4

This article is cited by

-

Connecting gender norms and economic performance reveals gendered inequities in Malawian small-scale fish trade

Maritime Studies (2023)

-

Improving access to aquatic foods

Nature Food (2022)