Abstract

In this study, oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus) mushroom was cultivated from hazelnut branches (HB) (Corylus avellana L.), hazelnut husk (HH), wheat straw (WS), rice husk (RH) and spent coffee grounds (CG). Hazelnut branch waste was used for the first time in oyster mushroom cultivation. In the study, mushrooms were grown by preparing composts from 100 to 50% mixtures of each waste type. Yield, biological activity, spawn run time, total harvesting time and mushroom quality characteristics were determined from harvested mushroom caps. In addition, chemical analysis of lignocellulosic materials (extractive contents, holocellulose, α-cellulose, lignin and ash contents) were carried out as a result of mushroom production and their changes according to their initial amounts were examined. In addition, the changes in the structure of waste lignocellulosic materials were characterized by FTIR analysis. As a result of the study, 172 g/kg yield was found in wheat straw used as a control sample, while it was found as 255 g/kg in hazelnut branch pruning waste. The highest spawn run time (45 days) was determined in the compost prepared from the mixture of hazelnut husk and spent coffee ground wastes. This study showed that HB wastes can be used for the cultivation of oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus). After mushroom cultivation processes, holocelulose and α-cellulose content rates decreased while ash contents increased. FTIR spectroscopy indicated that significant changes occurred in the wavelengths regarding cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin components. Most significant changes occurred in 1735, 1625, 1510, 1322 and 1230 wavelengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are about 2000 edible mushroom species worldwide. Some of these mushroom species can be grown every day of the year when suitable conditions are created. The most commonly cultivated mushroom species are white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus), oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) and shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes)1. Oyster mushrooms reduce the blood glucose level and reduce the risk of cancer with its high level of nutrients1,2. Oyster mushrooms are the easiest to cultivate and have the shortest growing period when the necessary conditions are met. In addition, the costs required for cultivation are financially lower than other mushroom species. Because it can be easily grown on organic agricultural waste-based substrates. Compared to other mushroom species, it can be grown on very different substrate materials1,3,4. Normally, substrates rich in lignocellulosic materials such as straw, sawdust and cotton waste are preferred for growing mushrooms3,5,6. However, as substrates, palm cones, corn cobs7, sugarcane pulp, coconut fiber, sugarcane pulp and their combinations3, chickpea straw and sunflower heads8, cardboard and plant fiber9, hazelnut leaves, tilia leaves, wheat straw and European poplar leaves5 have also been tested and used in oyster mushroom cultivation so far. Among these substrates, wheat straw material is rich in lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose and can provide nutrients for mycelial growth and fruit formation. It has also been stated that it provides high biological efficiency5. However, according to Girmay9 and Mandeel et al.10, it was stated that sawdust exhibits low yield and performance, and the reason for this is that sawdust with low protein content is insufficient for fungal growth.

Although many lignocellulosic materials have the potential to cultivate oyster mushrooms, the nutrient content of lignocellulosic material appears to be a factor that significantly affects mushroom yield and growth. Substrates containing high lignin and cellulose have been reported to prolong the mushroom harvesting time, while those with high nutrient content have been reported to facilitate the colonization process of fungi compared to those with low content. It is stated that substrates with low nutrient content will cause contamination such as green mold11. Although all kinds of lignocellulosic materials can be used in oyster mushroom cultivation, some lignocellulosic materials may differ between countries and even regions in terms of availability5,12.

Turkey and Italy constitute the majority (80%) of the world hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) production13,14. In 2019, 1.125.178 tons of hazelnuts were produced worldwide14. Hazelnut husk and hazelnut branch pruning wastes appear after hazelnut harvest. Hazelnut husk and hazelnut branch are renewable resources and are not used in any field in the forest industry. For this reason, sufficient studies have not been done in the literature studies. It is used by local farmers by burning it in houses for heating purposes or it is used as a soil conditioner after harvest. However, burning for heating purposes causes environmental problems because it causes air pollution. As a result of hazelnut production, 1/5 of 1 kg of dried hazelnut comes out as husk. It is reported that approximately 3 × 105 tons of hazelnut shells (and husk) are released annually in Turkey15,16,17. Hazelnut husk and branch wastes are lignocellulosic materials and have a fibrous structure containing cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin17. This by-product (waste) can be used as a substrate for the cultivation of lignocellulosic fungi due to its high lignin content14.

While hazelnut husk waste has recently been used in mushroom cultivation, there is no reference to the use of hazelnut pruning wastes in mushroom cultivation. Hazelnut pruning wastes are usually caused by cutting old branches and newly born branches18. According to 2003 year data, it was reported that as a result of 0.65 million tons of hazelnut production, 0.45 million tons of hazelnut hard shell and 1.7 million tons of pruning waste were released19,20.

Coffee grounds waste is also a substrate that has recently been used for mushroom cultivation. It has been reported that 6 million tons of coffee grounds waste occur annually in the world. Cultivation of P.ostreatus from coffee grounds waste is seen as a new method for recycling this waste in developed countries21. Since coffee grounds contains 12.40% cellulose, 39.10% hemicellulose and 23.90% lignin, rot fungi can develop on its grounds22.

The purpose of this study is to cultivate medicinal and edible oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus) from some waste materials such as hazelnut branch pruning wastes, hazelnut husk, wheat straw, coffee grounds and rice husks. In the study, hazelnut branch pruning wastes were used for the first time in mushroom cultivation. In addition to the quality analyzes of the grown mushrooms, chemical changes (holocellulose, alpha cellulose, lignin amounts extractive substances and ash contents) in lignocellulosic materials were determined before and after mushroom cultivation. Chemical changes in lignocellulosic materials due to P. ostreatus activity were also characterized by FTIR spectrometry.

Materials and methods

Preparation of composts from lignocellulosic materials

Hazelnut branch/pruning wastes (Corylus avellana L.), hazelnut husk, wheat straw, spent coffee ground and rice husk wastes were used to cultivate Oyster mushrooms in the study. Hazelnut brunch (HB), hazelnut husk (HH) and wheat straw (WS) were supplied from growers and spent coffee ground (CG) was supplied from a local coffee company in the Düzce region in Türkiye. HB and HH were grinded in Wiley mill by the size of 1 cm. WS was used by size 5–6 cm and CG was 0.3–0.5 mm.

Air-dry 100% and 50% by weight homogeneous mixtures were prepared (w/w) (Table 1). The mixtures were wetted at regular intervals for 1 day, and their moisture was ensured to reach 50–55%. Then, 1 kg of each combination is weighed and filled into heat resistant polypropylene bags (28 × 42 cm) and kept in an autoclave at 121 °C for 1.5 h. 5 replicates were autoclaved for each combination. After sterilization, the pH and moisture contents of each mixture were determined. The autoclaved composts were left to cool overnight and allowed to reach a temperature of 24 °C (room temperature). Then, P. ostreatus spawn was inoculated into the composts at a rate of 2% compared to the dry compost weight in the air chamber. P. ostreatus spawn used in the study were purchased from Bursa Mantar company, Bursa, Türkiye. The spawn inoculated composts were mixed homogeneously and the bags were tightly tied and transferred to incubation room.

Incubation and harvest

The composts were kept in a dark environment at 22 ± 2 °C and 70% relative humidity in the air-conditioning room. After the mycelium colonization was completed, holes were drilled on the bags and the room temperature was set to 14–16 °C. Room humidity is increased to 80–90%. After this stage, incubation room was ventilated (with the CO2 level below 1000 ppm) and after the promordium formation was observed, 50–60 lx light per m2 was given to the room in order to promote the mushroom cap formation. The mushroom caps were harvested and were weighed on precision scales and their wet weights were recorded. A total of 3 flush mushrooms were harvested from each combination. Yield and biological activities of each combination were determined according to the mushroom cap weights with the following formula23.

In addition, spawn run time, days to first harvest (earliness) and total harvest time were recorded.

Nutrient content analysis of mushrooms

Ash, dry matter, moisture, oil, nitrogen, protein and element analysis of the harvested mushrooms were carried out in Scientific and Technological Research Application and Research Center (DUBIT) laboratory, Duzce, Turkey. Ash, dry matter, moisture, oil, nitrogen, protein and element analysis of the harvested mushrooms were determined according to Kacar24.

Chemical analysis of lignocellulosic materials

Determination of extractives

The raw control materials used before mushroom production (HB-C, HH-C, WS-C, CG-C and RH-C) and the remaining fungal degraded materials (HB-F, HH-F, WS-F, CG-F and RH-F) were ground and sieved in the Wiley mill. 40 mesh samples were dried in an oven (103 °C ± 2) and prepared for extractive content determination. 5 g of full dry samples were weighed and subjected to the acetone solvent extraction process for 6 h. Three replicates of each substrate type were carried out. After the extraction process was completed, it was vacuum filtered from the crucible (pore 2) and dried at 103 °C ± 2 for 12 h. The amount of extractive substance in the lignocellulosic materials was determined compared to the initial full dry weight. Extractive content of the substrates was determined according to TAPPI T 204 cm-1725 with some modifications.

Determination holocellulose content

Holocellulose determination was carried out according to the chloride method of Wise and John26. The method was applied to 5 different raw materials; hazelnut pruning waste, hazelnut husk, rice husk, coffee grounds and weat straw materials. Oven-dried extractive free 40-mesh samples (5 g) were placed in a 250 mL flask containing 160 mL of distilled water, 1.5 g of NaClO2, and 0.5 mL of glacial acetic acid and incubated at 78 °C for a period of time. The flask was shaken for 1 h and stirred at regular intervals throughout the reaction. After 1 h, 1.5 g of NaClO2 and 0.5 mL of glacial acetic acid were added to the mixture and heating was continued for 1 h. This process was repeated four times and when chlorination was complete, the mixture was filtered through a glass crucible (por 2). After the residue was washed repeatedly with acetone followed by cold distilled water, then dried in an oven at 103 ± 2 °C. The holocellulose content (%) was then determined relative to the initial full dry weight.

Determination alpha-cellulose content

Alpha-cellulose content was determined according to TAPPI T 203 cm-0927 standard using 17.5% NaOH on holocellulose samples. About 2 g of oven-dried holocellulose were placed in a beaker and 10 mL of 17.5% NaOH solution was added. This mixture was mixed twice with 5 mL of 17.5% NaOH solution at 5-min intervals and then kept in a water bath at 20 °C for 30 min. Then, 33 mL of distilled water was added to the mixture and kept at 20 °C for 60 min, and then filtered through a por 2 crucible. The residue in the crucible was first washed with 100 mL of 8.3% NaOH solution, then with 15 mL of 10% acetic acid and 250 mL of distilled water, and dried at 105 ± 3 °C and weighed. Finally, the % a-cellulose content was determined relative to oven dried holocellulose.

Determination of lignin content

The amount of removed component from the wood by chloritization from the extractive-free material in holocellulose determination was accepted as lignin. This is the theoretical lignin content.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) assesment

FTIR (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy) is a fast and non-destructive technique that has been successfully used to detect chemical compounds in complex structures. The most intriguing application of this technique is currently seen as explaining the degradation processes of various agricultural wastes for mushroom cultivation14.

FT-IR analyzes were performed in Düzce University Scientific and Technological Research Laboratory. Hazelnut branch, hazelnut husk, wheat straw, coffee grounds and rice husks were ground before analysis and dried at 103 °C ± 2 for 12 h. The absorption spectra of the substrates used were obtained by the KBr (Potassium Bromide) technique based on pellet formation. Since this method gives less noisy peaks than the methods obtained with other ATR, FT-IR (4 cm−1, 40 scan) was preferred. In each analysis, approximately 5–10 mg of substrate and 1% of the substrate weight of KBr powder were mixed and pressed into pellets for the FT-IR measurement.

Statical analysis

Differences in yield, biological efficency, spawn run time, and total harvest time of the mushrooms obtained according to the type of waste lignocellulosic material and the differences between the chemical components of the lignocellulosics were evaluated with one-way ANOVA. Duncan's means discrimination test was applied at the level of α = 0.05 for the variables determined to have differences between the groups according to the ANOVA results.

Research involving plants

The authors complied with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research involving Endangered Species and the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Results and discussion

Table 2 shows the yield and biological efficiency values for the each substrate. According to the Table 2, the differences between the substrates in terms of mushroom yield and biological activity values were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). The highest yield (257 g/kg) and biological efficiency (64%) values were determined in mixtures of 1RH: 1CG. In addition, 255.7 g/kg yield value and 63.9% biological efficiency were determined in the substrate prepared from HB alone. There was no statistical difference between the yield and biological efficiency values of mushrooms produced from HB alone and that of 1RH: 1CG mixtures (P < 0.005). The lowest yield was obtained in the substrates prepared by mixing HB and CG. In the literature studies, wheat straw is used as a control sample in the cultivation of P. ostreatus. In this study, a yield of 172.5 g/kg was found in WS alone. When HB and CG were added to the WS substrates, the yield and biological efficiency value increased, while decreased with the addition of HH substrates.

When WS, RH, CG and HH were added to the HB substrates, the yield and biological efficiency value of these mixtures decreased. While the yield value of mushrooms prepared with CG alone was higher than those produced with 1:1 ratio ones, the yield and biological efficiency value of the combinations produced only with RH and CG were lower than CG alone.

It has been revealed by many studies that yield and biological efficiency values differ according to the type of substrate used. In literature studies, wheat straw is used as a control sample in mushroom cultivation. The mushroom yield obtained from the HB used for the first time in this study was found to be higher than that of WS, but there was no statistical difference between them. When WS and HB are used as a mixture in a ratio of 1:1, there was no statistical difference between them in terms of yield and biological efficiency. For this reason, it can be recommended to use HB as an alternative to WS or using their combinations. Pekşen and Küçükomuzlu28 revealed that mixtures prepared with hazelnut husk gave lower biological activity than wheat straw. Yildiz et al.5 obtained the highest yield and biological efficiency values in mixtures of wheat straw and waste paper prepared with hazelnut leaves, sawdust, wheat straw, waste paper, European poplar leaves and tilia leaves substrates. Fanadzo et al.29 studied wheat straw (Triticum aestivum), maize stover (Zea mays L.), thatch grass (Hyparrhenia filipendula) and oil/protein rich supplements ((maize bran, cottonseed hul (Gossypium hirsutum)) and they stated that maize stover is a more suitable lignocellulosic material for the cultivation of P. ostreatus than wheat straw.

Table 3 shows spawn runtime, days to first harvest time (earliness) and total harvest time according to the substrate types used in the study. Statistically significant differences were found between spawn run times, earliness and total harvest time of the substrates (P < 0.005). According to Table 3, the longest spawn run time (45 days) was determined in substrates prepared with 1HH:1CG while the lowest spawn run time was 15 days in the substrates prepared with 1RH:1CG. Spawn run times did not differ statistically between mixtures of HB, WS, 1HB:1WS, 1HB:1CG, 1HB:1RH and 1RH:1CG. The first harvest times (earliness) were also similar to the spawn run time. When the average total harvest times are examined, the highest harvesting time (83 days) was obtained in the substrates prepared from the mixture of 1HB:1HB, while the lowest (41.7 days) determined in the mixtures prepared with HB and WS.

When lignocellulosic material was used alone, the lowest spawn run time was found in WS and HB substrates. The short spawn run time in wheat straw is due to the shorter fermentation time and less nutrient requirement since it contains 39/51% cellulose, 76% holocellulose, 18% lignin, 3.5% protein and 0.6% digestible protein5. The long spawn run time in substrates alone and mixtures of CG and HH may cause the development of green molds due to contamination and a decrease in yield values30. High spawn run time in HH was revealed by Puliga et al.14 as well. On the other hand, Carrasco-Cabrera et al.21 reported that coffee grounds increase spawn run time. The long spawn run time in coffee wastes may be due to the very thin and small size of the coffee particle geometry31.

The properties of some nutrients (ash, dry matter, moisture, oil, nitrogen and protein) of mushrooms obtained from substrates are shown in Table 4. When nutrient values of mushrooms obtained from HB were examined, ash and dry matter were generally higher than that of other substrates, while moisture value was lower. When protein and nitrogen contents are considered, the amount of nitrogen and protein in mushrooms obtained from coffee to coffee supplemented substrates was generally found to be high. The lowest amount of protein and nitrogen was determined in mushrooms cultivated from wheat straw alone. In cases where protein needs are required, mushrooms can be produced by supplementing with CGs. The highest amount of oil was determined from mushrooms produced from CG alone, while the lowest was obtained in mixtures of 1HB:1RH.

Elemental contents of mushrooms obtained from substrates prepared from different types of lignocellulosic wastes are given in Table 5. Significant differences were detected between the elemental contents of the mushrooms obtained from the substrates. The highest amounts of the nutrients P (26,288 mg/kg), Mg (3510 mg/kg), K (48,347 mg/kg), Fe (133.89 mg/kg), Mn (15.85 mg/kg), Cu (33.29 mg/kg) and Zn (98.26 mg/kg) were detected in mushrooms cultivated from HH substrate. In the study, Na (746 mg/kg) element in mushrooms obtained from HB waste which was used in mushroom cultivation for the first time was found to be higher than mushrooms obtained from the other substrates. The amount of Mn in mushrooms obtained from HB was found to be 5.19 mg/kg, that lower than mushrooms obtained from other substrates. Mineral analysis for P.ostreatus in this study resembled those recorded by Ananbeh and Almomany32.

Chemical analysis of lignocellulosic materials used in the study

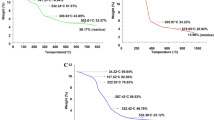

According to the substrate types, the amounts of holocellulose, alpha cellulose and lignin before and after mushroom cultivation are shown in Fig. 1. Among the substrate types, the highest amount of holocellulose (77.4%) before fungal degradation was detected in the RH-C (Rice Husk Control) sample, while the lowest was detected by 46.9% in the HH-C (Hazelnut Husk Control). It was observed that the amount of holocellulose decreased after fungal degradation. In the study, 67% holocellulose, 57.4% alpha cellulose and 33% lignin were detected in HB material, which was evaluated for the first time in mushroom production. In a previous study cunducted by Gençer and Özgül33, holocellulose was found to be 82.07%, alpha cellulose 41.33, Lignin 15.89%, ash 0.72% and extractive substance 2.83% in the HB undegraded control sample. The amounts of holocellulose, alpha cellulose, lignin and ash in the HH undegraded control sample were determined as 55.1%, 34.5%, 35.1% and 8.22%, respectively, in a previous study cunducted by Güney17. When the alpha cellulose ratios of the substrates were examined, the highest alpha cellulose ratio was found in the CG substrate type among the control samples. A decrease in alpha cellulose was observed in all substrate types after fungal degradation. When the lignin amounts were examined, there was an increase in the lignin ratio after the fungal attack compared to the control samples with the effect of degradation.

Chemical analysis findings of before and after mushroom cultivation according to substrate types. Note C, Control for each substrate/before cultivation; F, Fungal degraded for each substrate/after cultivation (HB-C: Hazelnut branch control /before mushroom cultivation; HB-F, Hazelnut branch fungal degradation/after mushroom cultivation (the other substrates were designed similarly in the Figure)).

The decrease in holocellulose and alpha cellulose ratios was also indicated in a study conducted by Atila34 and Jonathan et al.35. The decrease in macromolecules in lignocellulosic materials after mushroom production is due to the use of these structures by P.ostreatus both during mycelial growth and during fruitbody formation. P. ostreatus fungal hyphae secrete large amounts of extracellular enzymes that cause degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin36. However, since the secreted enzymes act selectively, they can degrade the cell wall components at different rates. The decrease in the amount of holocellulose in the HB substrate was lower than in the other substrates. This may be due to the fact that the HB substrate has a more dense and compact structure. It can be said that the reason for the proportional increase or constant rather than the decrease in the amount of lignin is that lignin is more difficult to decompose than cellulose and hemicellulose due to its complex structure37.

Lignin plays a critical role carbon cycling on earth. Its heterogeneous structure provides rigidity to plants and protects cellulose and hemicellulose from degradation38,39. This rigid structure effected the oyster mushroom yield and biological efficiency in the study. HB gave the highest yield and biological efficiency of 255,7 g, 63.9%, while HH gave the lowest of yield and biological efficiency of 157.5 g, 39.4%, respectively. When the lignocellulosic contents of the substrates with the yield of mushrooms produced were compared it was observed that HB had the high α-cellulose content of 57.4% and low lignin content of 30%. Addition, HH had the highest lignin content of 53.1% in the current study. This findings can be atrubuted that since lignin component of the substrates is a heterogeneous and irregular arrangement of phenylpropanol polymer, it resists enzymatic degradation of fungus and protects the cellulose component. When cellulose component is digested, glucose and cellobiose sugars are produced that allows to consume by fungi. It seems that consumption of the sugars by the fungi (P. ostreatus) was limited by the lignin40.

Extractive contents, ash, and pH values of the substrates used in the study are shown in Table 6. When extractive contents were examined, the highest extractve content (12.7%) were detected in CG-C among the undegraded substrates while lowest extractive (0.07%) was detected in RH-C. According to obtained data from the study, extractive contents significantly increased in the HB-F, WS-F and RH-F compared to their undegraded controls in contrast to HH-F and CG-F (P < 0.05). The findings in Table 6 showed that ash content significantly increased in fungal degraded substrates (P < 0.05). The highest ash content was recored by 35. 5% in RH-F. After mushroom cultivation ash ratios increased by more than 100% in fungal degraded substrates compared to initial substrates. Similar results were also found in a study cunducted by Zhang and Fadel41. pH values of the substrates decreased when compared to initial values after fungal cultivation.

FTIR assessment

The FTIR spectra in the fingerprint region (1800–600 cm−1) showing the changes in the structure after the fungal attack of the wheat straw, hazelnut branch, hazelnut husk and rice husk compared to the control are given in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5. The peaks occurring in this region represent lignin and polysaccharides in lignocellulosic materials (Table 7). The bands at 1730 cm−1 represent unconjugated C=O vibrations originating from the acetyl and carboxylic acid structures in xylan (hemicellulose)46,47,48. While a slight decrease was observed in the peak intensity of the wheat straw in this region, no significant change was observed in the other samples. Broadband in the range of 1680–1560 cm−1 represent the C=C and C=O stresses of the lignin aromatic chain (1630 cm−1)48,52, the C–O stretching of the lignin aromatic skeleton vibration (1595 cm−1)46,47,53 and the O–H deformation of the absorbed water (1640 cm−1)46. The overlap effect of these groups caused the formation of a broad peak. It is observed that this band intensity increased significantly in all samples. Visibility of vibrations in this region is increased by lignin degradation of P. ostreatus. The bands at 1510 cm−1 represent aromatic C–O stretching vibrations of lignin46,50,53. C–H deformations of CH2 and CH3 groups in lignin and hemicelluloses and CH2 in-plane bending vibrations of cellulose and lignin are observed in 1455 and 1418 cm−1 bands, respectively. The bands at 1370 cm−1 represent symmetrical and asymmetrical C–H deformation vibrations of cellulose and hemicelluloses42,50,52,54. The bands at 1320 cm−1 represent the CH2 in-plane bending vibration found at the C6 of the crystalline cellulose50. In all lignocellulosic materials, an increase in the intensity of these bands is observed with the fungal effect. This increase is related to the increase in peak lengths with crystalline regions appearing more prominently as P. ostreatus cellulose degrades the amorphous regions. It is seen that this effect is more in RH compared to other lignocellulosic materials. The band at 1230 cm−1 is associated with C–O stretching vibrations between lignin and xylan (hemicellulose)47. It represents the C–O–C stretching vibrations of shoulder glycosidic bonds at 1150 cm−156, the C–O stretching of band cellulose and hemicelluloses at 1030 cm−1, and the C–OH bending vibration of xylan52,54,57. In the 1150–900 cm−1 band, there is no significant change for WS, HH and HB, while the band intensity increases significantly in RH. Significant changes in the 1624, 1320 and 1034 cm−1 wavelengths reveal the degradation effect of P. ostreatus on lignin, cellulose and hemicelluloses in RH. The weak shoulder at 898 cm−1 is associated with β-(1 → 4) glycosidic bonds of cellulose48,52.

FTIR spectra of CG-C and CG-F is shown in Fig. 6. The C=O stretching vibration of the CG-C (un-degraded control sample) is observed in the 1743 cm−1 band42,43,44,45. This band is characteristic of the aliphatic ester groups found in coffee-specific quinic acid and lipids. In this region (around 1735 cm−1 band), there is also a C=O stretching vibration of unconjugated hemicellulose. It is seen that this band disappears due to fungal attack (P. ostreatus). C=O stretching vibrations associated with caffeine and C=C vibrations of lipids and fatty acids are observed in the 1652 cm−1 band42,45. At the same time, this band represents the C=C and C=O stresses of the lignin aromatic chain (1630 cm−1), the C–O stretching of the lignin aromatic skeleton vibration (1595 cm−1) and the O–H deformation of the absorbed water (1640 cm−1)45,51. Visibility of vibrations in this region increased with lignin degradation. Aromatic C–O stretching vibration of lignin is observed in the 1512 cm−1 band42. In the 1458 cm−1 band, there are C–H bending and C–H deformation vibrations of the methyl and methylene groups found in chlorogenic acids together with lignin and polysaccharides. Bands of chlorogenic acids (esters formed by quinic acid and some trans-cinnamic acids) are observed in the 1450–1050 cm−1 region. The C–O deformation of quinic acid is observed in the 1061 cm−1 band, and the O–H deformation in the 1371 cm−1 band. In the 1237, 1155 and 1061 cm−1 bands, the absorption of the C–O–C ester bond of quinic acid takes place44,55. The three bands seen in the 900–750 cm−1 region represent β-(1 → 4) glycosidic bonds of arabinogalactans, galactomannans, and cellulose polysaccharides58. There is a decrease in the intensity of these bands. C–H, C–O–C, C–N and P–O vibration types specific to polysaccharides are also exhibited in the 900–1400 cm−1 region. Due to the overlap of bands specific to cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, and chromatic acids, it is not possible to differentiate bands of these structures with FTIR. When considering the changes in the bands of the 1800–600 cm−1 fingerprint region, it is seen that P. ostreatus affects chlorogenic acids and cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin structures in lignocellulosic structure.

Conclusion

In this study, P. ostreatus mushroom was cultivated for the first time from HB wastes. In addition, HH, CG, RH and WS were evaluated as substrate material by forming a mixture with HB wastes. As a result of the study, P. ostreatus mushroom was successfully grown in HB wastes. In addition, changes in the structure of lignocellulosic materials were characterized by chemical analyzes and FTIR studies. In the study, the highest yield value (255 g/kg) was determined in HB substrate, which was evaluated in mushroom cultivation for the first time while yield value was found to be 172 g/kg in WS used as control sample. α-cellulose and lignin content of the substrates effected yield and biological efficiencies of the mushrooms produced from the substrates alone. Spawn run time was found to be longer in HH and CG substrates compared to other substrates. After cultivation of P. ostreatus holocellulose and α-cellulose content rates decreased while lignin and ash content rates increased. FTIR spectroscopy assesments indicated that significant changes occured in the peaks of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin components. Overall, this study showed that HB wastes can be used for the P. ostreatus cultivation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wan Mahari, W. A. et al. A review on valorization of oyster mushroom and waste generated in the mushroom cultivation industry. J. Hazard. Mater. 400, 123156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123156 (2020).

Jedinak, A. & Sliva, D. Pleurotus ostreatus inhibits proliferation of human breast and colon cancer cells through p53-dependent as well as p53-independent pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 33, 1307–1313 (2008).

Das, D., Kadiruzzaman, M., Adhikary, S., Kabir, M. & Akhtaruzzaman, M. Yield performance of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on different substrates. Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 38, 613–623. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjar.v38i4.18946 (2014).

Sanchez, C. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and other edible mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1321–1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2343-7 (2010).

Yildiz, S., Yildiz, Ü. C., Gezer, E. D. & Temiz, A. Some lignocellulosic wastes used as raw material in cultivation of the Pleurotus ostreatus culture mushroom. Process Biochem. 38, 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(02)00040-7 (2002).

Liaqat, R. et al. Growth and yield performance of oyster mushroom on different substrates. Mycopath, 12, (2014)

Samuel, A. A. & Eugene, T. L. Growth performance and yield of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus [sic]) on different substrate composition in Buea South West Cameroon. Sci. J. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.7237/sjbch/139 (2012).

Iqbal, S. H., Rauf, C. A. & Sheikh, M. I. Yield performance of oyster mushroom on different substrates. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 7, 900–903 (2005).

Mandeel, Q. A., Al-Laith, A. A. & Mohamed, S. A. Cultivation of oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) on various lignocellulosic wastes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21, 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-004-3494-4 (2005).

Girmay, Z., Gorems, W., Birhanu, G. & Zewdie, S. Growth and yield performance of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq. Fr.) Kumm (oyster mushroom) on different substrates. AMB Express 6, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-016-0265-1 (2016).

Sofi, B., Ahmad, M. & Khan, M. Effect of different grains and alternate substrates on oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) production. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 8, 1474–1479. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2014.6697 (2014).

Labuschagne, P. M., Eicker, A., Aveling, T. A. S., de Meillon, S. & Smith, M. F. Influence of wheat cultivars on straw quality and Pleurotus ostreatus cultivation. Biores. Technol. 71, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-8524(99)00047-4 (2000).

Fideghelli, C. & De Salvador, F. R. World hazelnut situation and perspectives. In VII International Congress on Hazelnut 39–52. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.845.2 (2008).

Puliga, F., Leonardi, P., Minutella, F., Zambonelli, A. & Francioso, O. Valorization of hazelnut shells as growing substrate for edible and medicinal mushrooms. Horticulturae 8, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030214 (2022).

Cimen, F. et al. Characterization of humic materials extracted from hazelnut husk and hazelnut husk amended soils. Biodegradation 18, 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-006-9063-9 (2007).

Sürek, E. Prebiotic oligosaccharide production from hazelnut wastes. Doctoral dissertation, (Izmir Institute of Technology, Turkey, 2017).

Guney, M. S. Utilization of hazelnut husk as biomass. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 4, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2013.09.004 (2013).

Bak, T. & Karadeniz, T. Effects of branch number on quality traits and uield properties of European hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.). Agriculture 11, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11050437 (2021).

Alkaya, E., Altay, T., Ata, A., Çakar, S. O. & Durtas, P. Tarımsal atıklardan yüksek katma değerli biyoürün üretimi. Ileri teknoloji projeleri destek programı raporu 35 (2010).

Surek, E. & Buyukkileci, A. O. Production of xylooligosaccharides by autohydrolysis of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) shell. Carbohydr. Polym. 174, 565–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.109 (2017).

Carrasco-Cabrera, C. P., Bell, T. L. & Kertesz, M. A. Caffeine metabolism during cultivation of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) with spent coffee grounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 5831–5841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-09883-z (2019).

Chai, W. Y., Krishnan, U. G., Sabaratnam, V. & Tan, J. B. L. Assessment of coffee waste in formulation of substrate for oyster mushrooms Pleurotus pulmonarius and Pleurotus floridanus. Future Foods 4, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100075 (2021).

Peksen, A. & Yakupoglu, G. Tea waste as a supplement for the cultivation of Ganoderma lucidum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-008-9931-z (2008).

Kacar, B. Chemical analysis of plant and soil: III, Soil Analysis. Ankara Univ. Faculty of Agriculture, Education Res. Extension Found, Ankara (1994).

TAPPI T 204 CM-17 Solvent Extractives of Wood and Pulp, Standard by Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (2017).

Wise, L. E. & John, E. C. Wood chemistry Vol. 2 (Reinhold Publishing Co., 1952).

TAPPI T203 cm-09 Alpha-, beta- and gamma-cellulose in pulp. TAPPI Press, Atlanta (2009).

Pekşen, A. & Küçükomuzlu, B. Yield potential and quality of some Pleurotus species grown in substrates containing hazelnut husk. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 768–771. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2004.768.771 (2004).

Fanadzo, M., Zireva, D. T., Dube, E. & Mashingaidze, A. B. Evaluation of various substrates and supplements for biological efficiency of Pleurotus sajor-caju and Pleurotus ostreatus. Afr. J. Biotech. 9, 2756–2761 (2010).

Atila, F. Compositional changes in lignocellulosic content of some agro-wastes during the production cycle of shiitake mushroom. Sci. Hortic. 245, 263–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.10.029 (2019).

Membrillo, I., Sanchez, C., Meneses, M., Favela, E. & Loera, O. Particle geometry affects differentially substrate composition and enzyme profiles by Pleurotus ostreatus growing on sugar cane bagasse. Biores. Technol. 102, 1581–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.08.091 (2011).

Ananbeh, K. M. & Almomany, A. R. Production of oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus on olive cake agro waste. Dirasat Agric. Sci. 32, 64–70 (2005).

Gençer, A. & Özgül, U. Utilization of common hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) prunings for pulp production. Drvna industrija 67, 157–162. https://doi.org/10.5552/drind.2016.1529 (2016).

Atila, F. Biodegredation of different agro-endustrial wastes through the cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq. ex. Fr) Kummer. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 11, 1–9 (2017).

Jonathan, S. G., Akinfemi, A. & Adenipekun, C. O. Biodegradation and in-vitro digestibility of maize husk treated with edible fungi (Pleurotus tuber-regium and Lentinus subnudus) from Nigeria. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 9, 742–750 (2010).

Kuforiji, O. O. & Fasidi, I. O. Enzyme activities of Pleurotustuber-regium (Fries) singer, cultivated on selected agricultural wastes. Biores. Technol. 99, 4275–4278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.053 (2008).

Hatakka, A. Lignin-modifying enzymes from selected white-rot fungi: Production and role in lignin degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 13, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00039.x (1994).

Jefferies, T. Biodegradation of liqnin-carbohydrate complex. Biodegradation 1, 163–176 (1990).

Clarke, A. J. Biodegradation of Cellulose: Enzymology and Biotechnology (CRC Press, 1996).

Mercy, B., Sylvester, K. T. & Nathaniel, O. B. Effects of lignocellulosic in wood used as substrate on the quality and yield of mushrooms. Food Nutr. Sci. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2011.27107 (2011).

Zhang, R., Li, X. & Fadel, J. G. Oyster mushroom cultivation with rice and wheat straw. Biores. Technol. 82, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00188-2 (2002).

Pujol, D. et al. The chemical composition of exhausted coffee waste. Ind. Crops Prod. 50, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.07.056 (2013).

Craig, A. P., Franca, A. S., Oliveira, L. S., Irudayaraj, J. & Ileleji, K. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and near infrared spectroscopy for the quantification of defects in roasted coffees. Talanta 134, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2014.11.038 (2015).

Craig, A. P., Franca, A. S. & Oliveira, L. S. Evaluation of the potential of FTIR and chemometrics for separation between defective and non-defective coffees. Food Chem. 132, 1368–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.121 (2012).

Munyendo, L., Njoroge, D. & Hitzmann, B. The potential of spectroscopic techniques in coffee analysis—A review. Processes 10, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10010071 (2021).

Liu, R. & Huang, Y. Structure and morphology of cellulose in wheat straw. Cellulose 12, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CELL.0000049346.28276.95 (2005).

Bari, E. et al. Comparison between degradation capabilities of the white rot fungi Pleurotus ostreatus and Trametes versicolor in beech wood. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 104, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.03.033 (2015).

Yan, F., Tian, S., Du, K. & Wang, X. Effects of steam explosion pretreatment on the extraction of xylooligosaccharide from rice husk. BioResources 16, 6910–6920. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.16.4.6910-6920 (2021).

Razavi, Z., Mirghaffari, N. & Rezaei, B. Performance comparison of raw and thermal modified rice husk for decontamination of oil polluted water. Clean: Soil, Air, Water 43, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/clen.201300753 (2015).

Adapa, P. K., Tabil, L. G., Schoenau, G. J., Canam, T. & Dumonceaux, T. Quantitative analysis of lignocellulosic components of non-treated and steam exploded barley, canola, oat and wheat straw using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 1, 177–188 (2011).

Craig, A. P., Botelho, B. G., Oliveira, L. S. & Franca, A. S. Mid infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics as tools for the classification of roasted coffees by cup quality. Food Chem. 245, 1052–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.066 (2018).

Lun, L. W., Gunny, A. A. N., Kasim, F. H. & Arbain, D. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of paddy straw pulp treated using deep eutectic solvent. In Advanced Materials Engineering and Technology V AIP Conf. Proc. (Vol. 1835), 020049-1-020049-4. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4981871 (2017).

Akcay, C. & Yalcin, M. Morphological and chemical analysis of Hylotrupes bajulus (old house borer) larvae-damaged wood and its FTIR characterization. Cellulose 28, 1295–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03633-5 (2021).

Galletti, A. M. R. et al. Midinfrared FT-IR as a tool for monitoring herbaceous biomass composition and its conversion to furfural. Hindawi Publ. Corp. J. Spectrosc. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/719042 (2016).

Belchior, V., Botelho, B. G., Casal, S., Oliveira, L. S. & Franca, A. S. FTIR and Chemometrics as effective tools in predicting the quality of specialty coffees. Food Anal. Methods 13, 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-019-01619-z (2019).

Baeva, E. et al. Evaluation of the cultivated mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus basidiocarps using vibration spectroscopy and chemometrics. Appl. Sci. 10, 8156. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10228156 (2020).

Swantomo, D., Rochmadi, R., Basuki, K. T. & Sudiyo, R. Synthesis and characterization of graft copolymer rice straw cellulose-acrylamide hydrogels using gamma irradiation. Atom Indonesia 39, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.17146/aij.2013.232 (2013).

Reis, N., Botelho, B. G., Franca, A. S. & Oliveira, L. S. Simultaneous detection of multiple adulterants in ground roasted coffee by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and data Fusion. Food Anal. Methods 10, 2700–2709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-017-0832-3 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Süleyman KORKUT for providing laboratory facilities and his guidance for this project.

Funding

This research was supported financially by the Directorate of Scientific Research Projects of Düzce University (DÜBAP 2020.02.03.1131).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision. F.C.: Statistical Analysis, Writing–review and editing, Chemichal Analysis. R.A.: Investigation, Methodology, Chemichal Analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akcay, C., Ceylan, F. & Arslan, R. Production of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) from some waste lignocellulosic materials and FTIR characterization of structural changes. Sci Rep 13, 12897 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40200-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40200-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.