Abstract

Despite recent advances in the treatment of medulloblastoma, patients in high-risk categories still face very poor outcomes. Evidence indicates that a subpopulation of cancer stem cells contributes to therapy resistance and tumour relapse in these patients. To prevent resistance and relapse, the development of treatment strategies tailored to target subgroup specific signalling circuits in high-risk medulloblastomas might be similarly important as targeting the cancer stem cell population. We have previously demonstrated potent antineoplastic effects for the PI3Kα selective inhibitor alpelisib in medulloblastoma. Here, we performed studies aimed to enhance the anti-medulloblastoma effects of alpelisib by simultaneous catalytic targeting of the mTOR kinase. Pharmacological mTOR inhibition potently enhanced the suppressive effects of alpelisib on cancer cell proliferation, colony formation and apoptosis and additionally blocked sphere-forming ability of medulloblastoma stem-like cancer cells in vitro. We identified the HH effector GLI1 as a target for dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition in SHH-type medulloblastoma and confirmed these results in HH-driven Ewing sarcoma cells. Importantly, pharmacologic mTOR inhibition greatly enhanced the inhibitory effects of alpelisib on medulloblastoma tumour growth in vivo. In summary, these findings highlight a key role for PI3K/mTOR signalling in GLI1 regulation in HH-driven cancers and suggest that combined PI3Kα/mTOR inhibition may be particularly interesting for the development of effective treatment strategies in high-risk medulloblastomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medulloblastoma is one of the most common malignant brain tumours in paediatric patients accounting for approximately 20% of all paediatric brain tumours1. Though overall survival has improved with multimodal therapy including maximal surgical resection, radiation therapy, and multi-agent chemotherapy, this disease remains a significant cause of brain cancer morbidity and mortality2. Genomic studies have revealed four molecular subgroups; Wingless/Integrated (WNT), Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), Group 3, and Group 43. These subgroups are biologically distinct and show differences in demographics, patterns of dissemination, and outcomes4. Of the 4 subtypes, SHH medulloblastoma is the most frequent in infants and adults5,6. Due to the very poor clinical outcome of some SHH medulloblastoma patients, the WHO has recently revised this classification, with new subclasses distinguishing between SHH, TP53 wild-type and SHH, TP53 mutant medulloblastoma7. Patients with SHH-driven medulloblastoma frequently exhibit either germline or somatic mutations and copy-number alterations in genes that regulate the Hedgehog (HH) signalling pathway such as PTCH1, SUFU, SMO, GLI1, GLI2 and MYCN8. As a consequence, these genetic changes result in constitutive transcriptional activation of HH target genes, such as glioma-associated oncogene (GLI) transcription factors, that can promote cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Aberrant HH signalling in cancer has led to the development of smoothened (SMO) inhibitors that target HH upstream components, thereby blocking target gene transcription9. However, SMO inhibitors in younger patients may result in complications due to the essential role of HH signalling during development10,11. Additionally, in humans and mice, SHH-type medulloblastomas acquire resistance to SMO inhibitors9,12,13. The aforementioned challenges outline major impediments for the utility of SMO inhibitors in paediatric cancers and have encouraged the search for alternative routes to target HH downstream effectors in SHH-driven paediatric cancers.

There is extensive crosstalk between the HH pathway and other pathways that can trigger GLI transcription factor activation in the absence of canonical HH signalling14. This has driven development of research seeking to identify putative oncogenic targets that are not part of the canonical HH pathway but stimulate GLI transcription factor activity through non-canonical routes. One such pathway is triggered by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/S6K1 mediated phosphorylation of GLI1, resulting in GLI1 nuclear translocation and activation of HH target genes15. Additionally, crosstalk between the mTOR and HH pathways cooperates to promote mRNA translation through inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) and stimulation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) expression16,17. Consistent with this, dual inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/mTOR and HH pathways has been shown to suppress tumour growth and increase survival in a medulloblastoma flank xenograft mouse model18. Importantly, upregulation of components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been reported in SMO resistant medulloblastomas and concurrent combination of SMO antagonists with PI3K/mTOR inhibitors blocks tumour growth and prevents the development of resistance to SMO inhibitors19,20. This key role for mTOR has recently been corroborated by another study, reporting that loss of mTORC1 function blocks development of SHH-driven medulloblastoma17. Remarkably, pharmacologic mTOR inhibition was found to reduce tumour growth and increase survival in a SMO inhibitor resistant medulloblastoma transgenic mouse model17. Thus, accumulating evidence indicates that blocking components of the PI3K/mTOR pathway may be a promising approach for HH driven cancers.

Activation of PI3K signalling has been reported in medulloblastoma and may contribute to development and progression of this cancer21,22,23. Importantly, strategies targeting PI3K are not limited to SHH-driven medulloblastoma because pharmacological PI3K inhibition has also shown promise in MYC-driven Group 3 mouse models of medulloblastoma23. Elevated PI3K/AKT activity in glioma stem cells suggests generally important roles for this pathway in brain cancer stem cells (CSCs)24. Additionally, the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated after irradiation in nestin-positive cells in medulloblastoma mouse models, likely to promote survival and resistance of CSCs21. Accordingly, inhibition of PI3K signalling was shown to inhibit proliferation and promote differentiation of stem-like cancer cells in medulloblastoma25. Further, our own studies have demonstrated a key role for the PI3Kα catalytic isoform (p110α) in sphere forming medulloblastoma cells and showed disruption of cancer stem cell frequencies after PIK3CA knockdown26. Taken together, the PI3K pathway is attracting increasing recognition as a potential target to eradicate brain CSCs regardless of medulloblastoma subtype.

While the important contributions of PI3K/AKT activation for medulloblastoma development suggest that PI3K inhibitors might show promise for the treatment of this tumour, the narrow therapeutic window of pan-PI3K inhibitors has been discouraging27. Efforts to determine the discrete roles of PI3K isoforms and the clinical utility of isoform-selective inhibitors for PI3Ks indicate improved target selectivity, with lower toxicity28. Recent advances in the development of inhibitors of the alpha catalytic isoform suggest PI3Kα may be of particular interest for therapeutic approaches29. However, several studies have found that selective PI3Kα inhibition results in activation of the mTOR pathway to promote survival and resistance30,31,32,33.

Here, we sought to investigate the therapeutic effects of combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition in medulloblastoma and in particular the effects on the CSC population. We report evidence for a discrete role of the PI3Kα/mTOR pathway in SHH subtype medulloblastoma. We found dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition strongly reduced the amount of nuclear GLI1 protein in HH-driven medulloblastoma and similar results were observed in Ewing sarcoma, another HH-driven paediatric cancer. Finally, combined PI3Kα and mTOR targeting disrupted cancer stem cell frequencies in vitro and significantly inhibited tumour growth in a flank tumour xenograft mouse model in vivo. These results suggest that selective PI3Kα targeting combined with mTOR inhibition has a therapeutic effect in medulloblastoma and potentially other HH-driven paediatric cancers.

Results

Alpelisib and OSI-027 inhibit PI3K/mTOR signalling and exhibit antineoplastic effects in medulloblastoma cells

Alpelisib is a PI3Kα-specific inhibitor with a tolerable safety profile34. However, several independent studies reported activation of resistance pathways, including mTORC1 signalling, that confer resistance to alpelisib in several solid tumours30,31,32,33. Thus, we sought to investigate the effects of simultaneous inhibition of PI3Kα and mTOR in DAOY and D556 medulloblastoma cells. We chose two cell lines that represent the highest risk category with very poor prognosis; DAOY representing the SHH, TP53 mutated and D556 representing the Group 3 MYC amplified category8,35,36. Combined treatment with alpelisib and the catalytic mTOR inhibitor OSI-027 decreased phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473), S6K1 (Thr389), and 4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) (Fig. 1A,B). These results suggest that combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition potently blocks signalling of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR axis in medulloblastoma. This prompted us to study the biological effects of combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition. Initial experiments examined the dose response curves for inhibition of cell viability by alpelisib and OSI-027. In DAOY and D556 cells, combination of alpelisib with OSI-027 resulted in stronger suppression of cell viability as compared to either agent alone (Fig. 1C,D). In DAOY cells, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) decreased from 12.31 μM (alpelisib) and 1.703 μM (OSI-027) to 0.59 μM for the combination treatment (alpelisib and OSI-027) (Fig. 1C). In D556 cells, the IC50 decreased from 21.2 μM (alpelisib) and 5.889 μM (OSI-027) to 3.035 μM for the combination of alpelisib and OSI-027 (Fig. 1D). We next calculated the combination index (CI) for this drug combination. The CI defines additive effects (CI = 1), synergism (CI < 1) or antagonism (CI > 1)37. The combination of alpelisib with OSI-027 resulted in synergistic effects in both cell lines with CI values of 0.393 for DAOY and 0.636 in D556 cells, respectively. These findings are consistent with potent synergistic inhibitory effects in both cell lines, with such synergism being more potent in SHH-driven DAOY cells as compared to D556 cells that represent Group 3 medulloblastoma. In further studies, we found growth of colonies in soft agar was also potently inhibited by the combination of alpelisib and OSI-027 (Fig. 1E,F). Additionally, the combination of the two agents increased the rate of apoptosis substantially more than either agent alone (Fig. 1G,H). Together, these results suggest that catalytic mTOR inhibition strongly enhances the antineoplastic effects of selective PI3Kα inhibition in medulloblastoma cells.

Alpelisib and OSI-027 inhibit PI3K/mTOR signalling and exhibit antineoplastic effects in medulloblastoma cells. (A,B) DAOY (A) or D556 (B) cells were treated with alpelisib (10 μM) and/or OSI-027 (10 μM) for 90 minutes and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-4EBP1T37/46 and phospho-S6K1T389. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with antibodies for 4EBP1, S6K1 and GAPDH. Lysates from the same experiment were run in parallel and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-AKTS473 followed by stripping and reprobing with antibodies for AKT. Blots were analysed by autoradiography. Uncropped blots are presented in the supplement. (C,D) DAOY (C) or D556 (D) cells in 96-well plates (2000 cells per well) were treated with alpelisib and/or OSI-027 at increasing concentrations for 5 days and cell viability was determined using the cell proliferation reagent, WST-1. Prism GraphPad 7.0 was used to determine IC50 values and CI values were calculated using Compusyn. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. (E,F) DAOY (E) or D556 (F) cells were seeded in soft agar in 96-well plates (1500 cells per well), treated with alpelisib (1 μM) and/or OSI-027 (1 μM). After 7 days, colony formation was quantified using the fluorescent CyQUANT GR Dye. Data represent means ± SEM of 5 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Unpaired one-way ANOVA, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (G,H) DAOY (G) or D556 (H) cells were treated with alpelisib (10 μM) and/or OSI-027 (2 μM). After 2 days, apoptosis was assessed by costaining cells with propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V-FITC followed by flow cytometry analysis. Annexin V positive cells were quantified to determine total apoptosis. Data represent means ± SEM of 4 (DAOY) and 5 (D556) independent experiments. Unpaired one-way ANOVA, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

PIK3CA expression is elevated in the SHH-subgroup and correlates with GLI1 expression in medulloblastoma

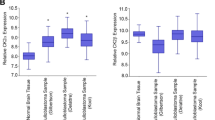

Recently, at least four major subtypes of medulloblastoma have been described3,38. We next sought to investigate whether distinct subgroups may show different dependencies on the PI3Kα signalling axis. Analysis using the Northcott dataset39 revealed that PIK3CA was most highly expressed in SHH subtype medulloblastoma (Fig. 2A). PIK3CA expression was also found to positively correlate with expression of the HH effector transcription factor glioma-associated oncogene 1 (GLI1) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, pathway enrichment analysis indicates that GLI1 expression is significantly associated with the “PI3K-AKT signalling pathway” in medulloblastoma (Fig. 2C). Together, these data indicate a correlation between PIK3CA expression and GLI1 in medulloblastoma and raise the possibility of a functional relationship between PI3Kα signalling and the GLI1 transcription factor in HH driven cancers.

PIK3CA expression is elevated in the SHH-subgroup and correlates with GLI1 expression in medulloblastoma. (A) PIK3CA expression was analyzed in different medulloblastoma subgroups from the Northcott_2012 dataset, downloaded from the GlioVis portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) and subjected to analysis in GraphPad Prism 7.0. Unpaired one-way ANOVA, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Gene expression data from the Northcott_2012 dataset were downloaded from the GlioVis portal and GraphPad Prism 7.0 was used for correlation analysis to compare PIK3CA expression with GLI1. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (C) Medulloblastoma patient data from the Northcott_2012 dataset were subjected to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for GLI1 using the GlioVis portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/). Bubble chart shows enrichment for the given pathway, where each point represents the enrichment level, the colour corresponds to the adjusted P-value (P.adjust), and the size corresponds to the number of genes enriched (Count). Y-axis label represents pathway (see bottom panel for detailed name of pathways), and X-axis label represents enrichment factor (amount of differentially expressed genes enriched in the pathway over amount of all genes in background gene set).

Dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition decrease the amount of nuclear GLI1 and exhibit potent antineoplastic effects in Ewing sarcoma cells

GLI1 phosphorylation by the mTOR/S6K1 pathway promotes GLI1 nuclear localization and transcriptional activity, providing a mechanism for smoothened (SMO)-independent GLI1 activation15. We examined the effects of PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition on GLI1 nuclear accumulation in SHH-driven medulloblastoma using nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation of DAOY cells with Lamin A/C and tubulin as nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively. Combination of alpelisib and OSI-027 resulted in a decrease of nuclear GLI1 protein amounts, which was more pronounced as compared to single agent treatment (Fig. 3A). Next, we sought to investigate whether this GLI1 regulation by PI3Kα/mTOR is also evident in other HH-driven paediatric cancers. GLI1 transcription is directly induced by Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1-Friend leukemia virus integration 1 (EWS-FLI1), which promotes carcinogenesis of Ewing sarcoma Family of Tumors (ESFT)40. Therefore, we employed two Ewing sarcoma cell lines (TC71 and RDES) to examine GLI1 cytoplasmic/nuclear distribution in this cancer. Importantly, in TC71 and RDES Ewing sarcoma cells, combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition resulted in reduced nuclear GLI1 (Fig. 3B,C). The reduction of GLI1 protein in the nucleus after dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition indicates a requirement for PI3Kα and mTOR activities to sustain nuclear GLI1 in HH-driven cancers. HH-driven cancers strongly depend on nuclear GLIs for transcriptional activation of GLI target genes to promote proliferation and tumorigenesis41. Therefore, reduced nuclear GLI protein may contribute to suppression of tumour cell proliferation. In line with this, TC71 and RDES Ewing sarcoma cells exhibited high sensitivity to alpelisib and OSI-027 with IC50 values in the nanomolar range for the alpelisib/OSI-027 combination (TC71: 74 nM; RDES: 189 nM) (Fig. 3D,E). Additionally, dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition significantly reduced anchorage-independent growth of TC71 and RDES cells in soft agar as compared to either drug alone (Fig. 3F,G). These data support a role for PI3Kα and mTOR activities in maintaining nuclear GLI1 protein and inhibition of PI3Kα and mTOR disrupts the accumulation of GLI1 in the nucleus which may, at least in part, contribute to greatly reduced cell viability and colony formation in HH-driven paediatric cancers.

Dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition decreases the amount of nuclear GLI1 and exhibit potent antineoplastic effects in Ewing sarcoma cells. (A) DAOY medulloblastoma cells were treated with alpelisib (10 μM) and/or OSI-027 (5 μM) for 12 hours. After cell fractionation, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against GLI1, Lamin A/C and tubulin. Membranes were analysed using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. (B) TC71 Ewing Sarcoma cells were treated with alpelisib (0.15 μM) and/or OSI-027 (0.15 μM) for 24 hours and subjected to cell fractionation and immunoblotting using antibodies against GLI1, Lamin A/C and tubulin. Membranes were analysed using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. (C) RDES Ewing Sarcoma cells were treated with alpelisib (0.15 μM) and/or OSI-027 (0.15 μM) for 24 hours and subjected to cell fractionation and immunoblotting using antibodies against GLI1 and Lamin A/C. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with antibodies against HDAC1. Membranes were analysed using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. Uncropped blots for (A–C) are presented in the supplement. (D,E) TC71 (D) or RDES (E) Ewing Sarcoma cells were treated with alpelisib and/or OSI-027 at increasing concentrations for 5 days and cell viability was determined using the cell proliferation reagent, WST-1. Prism GraphPad 7.0 was used to determine IC50 values. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. (F,G) TC71 (F) or RDES (G) Ewing Sarcoma cells were seeded in soft agar in 96-well plates (5000 cells per well), treated with alpelisib (0.3 μM) and/or OSI-027 (0.3 μM). After 10 days, colony formation was quantified using the fluorescent CyQUANT GR Dye. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Unpaired one-way ANOVA, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Inhibition of PI3Kα or PIK3CA knockdown reduces sphere formation and disrupts medulloblastoma stem cell frequencies when combined with pharmacologic mTOR inhibition

Next we sought to test the effects of combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition on stem-like cancer cells grown in 3-D. Ewing sarcoma spheroids may not represent a reliable system to study stem-like cancer cell biology42. By contrast, we and others have shown that medulloblastoma cells grown under cancer stem cell conditions form 3-D neurospheres that adopt cancer stem cell characteristics26,43,44,45. We have also demonstrated a key role for the alpha catalytic PI3K isoform in medulloblastoma sphere-forming cells26. Therefore, we used medulloblastoma neurospheres grown in 3-D to study sphere-forming ability of stem-like cancer cells. Neurosphere growth was potently inhibited by alpelisib and OSI-027 and combination of both inhibitors resulted in significantly stronger blockade of neurosphere growth than either drug alone (Fig. 4A,B). These results indicate greatly reduced sphere-forming ability of medulloblastoma neurospheres after dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition.

Inhibition of PI3Kα or PIK3CA knockdown reduces sphere formation and disrupts medulloblastoma stem cell frequencies when combined with pharmacologic mTOR inhibition. (A,B) DAOY (A) or D556 (B) cells were grown as spheres in CSC medium for 7 days. Spheres were dissociated and seeded at 500 cells/well into round-bottom 96-well plates in the presence of alpelisib (5 μM) and/or OSI-027 (1 μM). After 7 days, spheres were stained with acridine orange and imaged to determine cross-sectional area. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Unpaired one-way ANOVA, **P ≤ 0.01, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Representative images are shown in the top panels. Scale bar, 1,000 μm. (C,D) In vitro ELDA after PIK3CA knockdown in combination with mTOR inhibition. DAOY (C) and D556 (D) cells were transfected with control siRNAs (siCtrl) or siRNAs targeting PIK3CA (siCA). After 2 days, cells were dissociated with trypsin and seeded in 3–5 technical replicates (n = 3) into round-bottom 96-well plates by forward- and side scatter, single-cell sorting at densities of 10, 30, 100, 300, 1,000 or 3,000 cells per well. Cells were treated with DMSO or OSI-027 (2 μM). After 7 days, neurospheres were stained with acridine orange and imaged using a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging multi-Mode Reader with a 4x objective. Neurospheres with a diameter of ≥100 μm were scored positive for ELDA analysis (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/). (E,F) Stem cell frequencies of medulloblastoma stem-like cancer cells for DAOY (E) or D556 (F) were estimated as the ratio 1/x with the top and bottom 95% confidence intervals, where 1 = stem cell and x = all cells. (G,H) P values from χ2 analyses are shown for DAOY (G, left panel) and D556 (H, left panel). Whole cell lysates of DAOY (G, right panel) and D556 (H, right panel) were subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against p110α to monitor knockdown of PIK3CA. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with antibodies against HSP90. Blots were analysed by autoradiography. Uncropped blots are presented in the supplement.

We have previously investigated distinct roles for Class IA PI3K isoforms and reported that expression of PIK3CA correlates with the expression of pluripotency/stem cell markers in medulloblastoma suggesting an important role for PI3Kα in the biology of medulloblastoma CSCs26. In line with this, we demonstrated an essential role for PIK3CA but not PIK3CB or PIK3CD in maintaining self-renewal capacities of stem-like cancer cells as judged by disruption of stem cell frequencies after knockdown of Class IA catalytic isoforms in extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA)26. However, evidence from breast cancer suggests a role for mTORC1 in resistance to selective PI3Kα inhibition and thus a requirement for mTORC1 blockade to enhance efficacy of PI3Kα inhibition30,32. Also, our previous work has demonstrated that the effects of PIK3CA knockdown or pharmacological PI3Kα inhibition can be enhanced by concomitant inhibition of pro-survival pathways in medulloblastoma26. Therefore, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to determine a possible role for mTOR activity in maintaining CSC frequencies after PIK3CA knockdown. PIK3CA knockdown strongly reduced the proportion of cells with self-renewal capacity in both DAOY (Fig. 4C) and D556 (Fig. 4D) cells. Importantly, the combination of OSI-027 with PIK3CA knockdown significantly reduced stem cell frequencies over either PIK3CA knockdown or OSI-027 single agent alone. Specifically, stem cell frequencies in DAOY dropped from 1 in 394.2 cells for PIK3CA knockdown or 1 in 544 for OSI-027 to 1 in 1526.8 for the combination PIK3CA knockdown and OSI-027 (Fig. 4E). Similar results were observed for D556 where stem cell frequencies decreased from 1 in 221.1 for PIK3CA knockdown or 1 in 123.4 for OSI-027 to 1 in 1366.4 for the combination (Fig. 4F). Chi-square analysis revealed these changes in stem cell frequencies were highly significant (Fig. 4G,H left panels). Knockdown of p110α protein was monitored by western blot analysis (Fig. 4G,H right panels). These results indicate that pharmacologic mTOR inhibition enhances the disruptive effects of PIK3CA knockdown on stem cell frequencies and suggest dual inhibition of PI3Kα and mTOR is required to efficiently block self-renewal capabilities of medulloblastoma CSCs.

Dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition reduces tumour growth in a medulloblastoma flank tumour xenograft

Given the potent antineoplastic effects of alpelisib and OSI-027 in vitro, we next sought to investigate the effects of dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition in vivo. As DAOY cells are representatives of high-risk SHH-driven medulloblastoma35, we used a DAOY medulloblastoma flank tumour xenograft mouse model to study the antitumor activity of combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition. DAOY cells in matrigel were injected subcutaneously in the flanks of nude mice and when tumours were palpable, mice were treated with vehicle controls (VC), alpelisib, OSI-027 or the alpelisib/OSI-027 combination (5 days treatment, 2 days rest followed by another 4 days treatment). While each drug moderately reduced the rate of tumour growth relative to vehicle control treated mice, the alpelisib/OSI-027 combination significantly reduced tumour growth as compared to either drug alone (Fig. 5A). The absence of obvious changes in body weight suggests that the combination of alpelisib with OSI-027 at these concentrations was well tolerated while still reducing tumour growth (Fig. 5B).

Dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition reduces tumour growth in a medulloblastoma flank tumour xenograft. (A) Tumour volumes from a flank xenograft mouse model are shown. Nude mice were injected subcutaneously into the left flank with DAOY cells (5 × 106 cells/mouse). Once mice showed palpable tumours, mice were randomized into vehicle control (VC; n = 10), alpelisib (50 mg/kg; n = 9), OSI-027 (25 mg/kg; n = 9) or combination (alpelisib and OSI-027; n = 10) groups. Mice were treated by oral gavage for 5 days, then 2 days rest followed by another 4 days of treatment (indicated by purple boxes). Two-way ANOVA for day 55; **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Body weight of mice from flank tumour xenograft experiment. Mouse body weight from experiment in A was recorded every other day throughout the study.

Discussion

Current treatments have produced promising results for many patients diagnosed with medulloblastoma, but not for patients with high-risk tumours. Due to the poor prognosis of some SHH medulloblastomas, the 2016 WHO consensus conference has reclassified subgroups into: WNT, SHH and TP53 wild-type, SHH and TP53 mutant, and non-WNT/non-SHH (encompassing Group 3 and Group 4 within this subgroup)7. Together with Group 3, metastatic and Group 3 MYC amplified medulloblastoma, SHH, TP53 mutant medulloblastoma has been identified as the highest risk category with very poor prognosis, as evident from 5-year overall survival rates of only 41%8,36. This very poor prognosis resulted in listing these patients with SHH, TP53 mutations as their own category by the WHO7,46.

In the current study, we investigated the effects of combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition in two of the highest risk category medulloblastoma cells, with DAOY cells representing the SHH, TP53 mutant and D556 cells representing the Group 3 MYC amplified categories35. The p110α isoform is highly expressed or activated among medulloblastoma patient samples47, and several investigations have been reporting promising results for targeting PI3K signalling in the SHH-driven subgroup17,18,19 and the MYC-driven Group 323,48. We utilized the PI3Kα selective inhibitor alpelisib, because the alpha catalytic isoform p110α exerts important roles in medulloblastoma47,49 and is the only Class IA PI3K essential for sphere-forming ability and stem cell frequencies in medulloblastoma stem-like cancer cells26. Isoform-selective PI3Kα inhibitors are now extensively exploited because of higher efficacy and lower toxicity as compared to pan-PI3K inhibitors29. Alpelisib is one such PI3Kα selective inhibitor with encouraging results in early phase clinical trials and has a suitable safety profile34. However, it has been reported that tumours develop resistance to alpelisib by activation of the mTOR pathway30,31,33. Therefore, we reasoned that alpelisib should be tested in combination with pharmacological mTOR inhibitors. We found that the combination of alpelisib with the catalytic mTOR inhibitor OSI-027 efficiently blocked signalling of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, exhibited potent antineoplastic effects, induced apoptosis and inhibited sphere formation. Additionally, knockdown of PIK3CA (encoding p110α) in combination with OSI-027 disrupted stem cell frequencies. Thus, dual PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition is a comprehensive strategy that includes targeting the CSC population and therefore shows promise for treatment of high-risk category medulloblastoma in different subgroups.

Interestingly, PIK3CA expression is highest in the SHH subgroup (see Fig. 2A). Also, expression of the HH effector GLI1 correlates with PIK3CA expression and is associated with enrichment of the PI3K-AKT pathway (see Fig. 2B,C). GLI transcription factors are the main downstream effectors of the canonical and the non-canonical HH cascade and are involved in the stimulation of multiple oncogenic signalling pathways41. We found nuclear GLI1 protein amounts were reduced in DAOY cells after combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition, indicating a role for PI3K/mTOR signalling in the regulation of GLI1 in the SHH subgroup. This observation prompted us to further investigate the mechanistic role of PI3Kα and mTOR in additional HH-driven paediatric cancers.

Survival and tumorigenesis of Ewing sarcoma is dependent on EWS-FLI1, a constitutively active chimeric transcription factor50. The HH effector GLI1 is a direct transcriptional target of EWS-FLI1 and exerts key roles in Ewing sarcoma tumorigenesis40. We chose Ewing sarcoma because this tumour type was shown to directly dependent on GLI1 and knockdown or inhibition of GLI1 exerts antineoplastic effects in this cancer40,51,52. We found that combination of alpelisib and OSI-027 resulted in substantial reduction of GLI1 nuclear protein. This suggests that continuous activity of the PI3K/mTOR axis is required to maintain high levels of GLI1 in the nucleus and inhibition of this pathway results in a reduction of nuclear GLI1 protein amounts. This is in agreement with the finding that the mTOR downstream effector S6K1 directly phosphorylates GLI1, resulting in nuclear translocation and activation of GLI1 independent of SMO15. Significantly, Ewing sarcoma cells were highly sensitive to PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition with IC50 values in the nanomolar range for the combination of both inhibitors. These findings suggest that PI3K/mTOR signalling contributes to tumorigenesis in HH-driven paediatric cancers through non-canonical activation of HH downstream effectors independently of canonical HH signalling through SMO. They further raise the possibility of targeting the PI3K/mTOR axis as a promising therapeutic approach in HH driven cancers that are resistant to SMO inhibitors. This notion is supported by the finding of the TC71 Ewing Sarcoma cell line showing resistance to the SMO inhibitor cyclopamine40, while being highly susceptible to combined PI3Kα and mTOR inhibition in the nanomolar range. This is of particular interest because medulloblastomas resistant to SMO inhibitors have been shown to activate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway19,20. Thus it is possible that increased PI3K and mTOR activities contribute to SMO inhibitor resistance by sustaining high nuclear GLI1 levels. In line with this, PI3K/mTOR inhibitors interfere with the development of resistance to SMO inhibitors in medulloblastoma19. Hence, PI3Kα/mTOR targeting might be a promising strategy for HH-driven cancers that are resistant to SMO inhibitors.

Here, we demonstrate potent anti-tumor effects after dual PI3K/mTOR inhibition that may be mediated, at least in part, by disrupting nuclear GLI1. Still, given the complexity of the crosstalk between the HH and PI3K/mTOR pathways, it is possible that inhibitory effects on additional pathway components contribute to these antineoplastic effects. Further mechanistic studies will be required to elucidate to which extent the disruption of stem cell frequencies, the inhibition of mTOR mediated mRNA translation and the inhibitory effects on nuclear GLI1 protein contribute to this phenotype. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that HH-driven paediatric cancers can be targeted by inhibition of the PI3K/mTOR pathway and raise the interesting possibility that this strategy might be exceptionally efficient in cancers that are highly dependent on non-canonical HH signalling and that are resistant to SMO inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

DAOY and D556 medulloblastoma cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and gentamycin (0.1 mg/ml). TC71 and RDES Ewing sarcoma cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 ng/ml). 3-D stem-like cancer cell cultures were described in detail previously26,53,54. The identity of established cell lines was authenticated by short-tandem repeat (STR) analysis (Genetica DNA Laboratories) in December 2017 (medulloblastoma lines) and August 2016 (Ewing sarcoma lines). All cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Aleplisib (BYL-719) and OSI-027 were purchased from ChemieTek and dissolved in DMSO as vehicle for in vitro studies.

Immunoblotting and antibodies

Cells were lysed in phosphorylation lysis buffer (pH 7.9) containing 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Roche). For cell fractionation, the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher) was used according the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentration was quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) with the Synergy HT plate reader and Gen5 software (Biotek). Equal amounts of protein lysate were subjected to SDS–PAGE (Bio-Rad) followed by transfer to Low Fluorescent PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA or 5% milk and cut horizontally to allow for incubation with different primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then incubated in secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody for 1 hour, and analysed using the WesternBright ECL substrate (GE Healthcare) and either autoradiography film (Denville Scientific) or the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System and Image Lab 5.0 software (Bio-Rad) as described26. Antibodies were removed, where indicated, using Restore PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher) to allow for incubation with additional antibodies. A comprehensive list of antibodies used in this study can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Uncropped blots are presented in the supplement.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (Roche) as described previously26. Briefly, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1,500 cells per well (for medulloblastoma cell lines) or 5,000 cells per well (Ewing sarcoma cell lines) with the indicated drugs. After incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 5 days, the WST-1 reagent (10% v/v) was added and cell viability was assessed using the Synergy HT plate reader and Gen5 software (BioTek) as described55. Apoptosis assay was done as described before56.

Soft agar assays

For investigation of anchorage-independent cell growth, soft-agar assays were performed using the CytoSelect 96-Well Cell Transformation Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, medulloblastoma and Ewing sarcoma cells were seeded in soft-agar in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 with the indicated inhibitors for 7 days (medulloblastoma cell lines) or 10 days (Ewing sarcoma cell lines) before agar was solubilized and cells were lysed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Colony formation was assessed as previously described55.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

For gene expression analysis, the GlioVis portal57 was employed to obtain data of the Northcott_2012 dataset39. These data were subjected to analysis in GraphPad Prism 7.0 as described before26. Also, statistical analyses were performed using Prism Graphpad 7.0, including calculation of IC50 values. For comparison of more than two groups one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used followed by Tukey’s test. For comparison of more than two groups and multiple time points, two-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey’s test. Comparison of stem cell frequencies of different groups for ELDA was done by Chi square (χ2) test. CI values were calculated for the IC50 values using Compusyn as described before58.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of gene expression

PIK3CA and control siRNA were from Dharmacon (GE Healthcare) and used with the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent and the Opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher) as described previously26.

Neurosphere assay and extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA)

DAOY and D556 cells were seeded at indicated cell concentrations in round-bottom 96-well plates (Costar) containing serum free media and the indicated drugs and incubated for one week at 37 C in 5% CO2. After 1 week, spheres were stained with acridine orange as previously described54. Spheres for neurosphere assay were imaged as described in26 and spheres for ELDA were imaged as described previously54. Extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) was carried out as previously described26 using the ELDA online software (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/).

DAOY flank tumour xenograft study

Mouse studies were carried out in accordance with approved protocols by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northwestern University. Five to 6-week-old athymic nude female mice (NU/NU strain 088; Crl:NU-Fox1nu) were purchased from Charles River and housed under aseptic conditions. Flank tumours were established by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 cells in Matrigel (Corning). Mice were monitored and tumours were measured by calliper as described before26. For in vivo studies, alpelisib was dissolved in Ora-Plus and OSI-027 was dissolved in 20% Trappsol in water and both drugs were administered by oral gavage. Mice were treated with (i) vehicle control (VC); (ii) alpelisib (50 mg/kg); (iii) OSI-027 (25 mg/kg); or (iv) the combination of alpelisib (50 mg/kg), and OSI-027 (25 mg/kg).

Data Availability

Datasets and analysis tools used in this study can be accessed from the GlioVis portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/).

References

Ostrom, Q. T. et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 19, v1–v88 (2017).

Massimino, M. et al. Childhood medulloblastoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 105, 35–51 (2016).

Northcott, P. A. et al. Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J Clin Oncol. 29, 1408–1414 (2011).

Taylor, M. D. et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 123, 465–472 (2012).

Ng, J. M. & Curran, T. The Hedgehog’s tale: developing strategies for targeting cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 11, 493–501 (2011).

Huang, S. Y. & Yang, J. Y. Targeting the Hedgehog Pathway in Pediatric Medulloblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 7, 2110–2123 (2015).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 803–820 (2016).

Northcott, P. A. et al. Medulloblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5, 11 (2019).

Girardi, D., Barrichello, A., Fernandes, G. & Pereira, A. Targeting the Hedgehog Pathway in Cancer: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Cells. 8 (2019).

Robinson, G. W. et al. Irreversible growth plate fusions in children with medulloblastoma treated with a targeted hedgehog pathway inhibitor. Oncotarget. 8, 69295–69302 (2017).

Rodon, J. et al. A phase I, multicenter, open-label, first-in-human, dose-escalation study of the oral smoothened inhibitor Sonidegib (LDE225) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 20, 1900–1909 (2014).

Robinson, G. W. et al. Vismodegib Exerts Targeted Efficacy Against Recurrent Sonic Hedgehog-Subgroup Medulloblastoma: Results From Phase II Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Studies PBTC-025B and PBTC-032. J Clin Oncol. 33, 2646–2654 (2015).

Yauch, R. L. et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 326, 572–574 (2009).

Carballo, G. B., Honorato, J. R., de Lopes, G. P. F. & Spohr, T. A highlight on Sonic hedgehog pathway. Cell Commun Signal. 16, 11 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. The crosstalk of mTOR/S6K1 and Hedgehog pathways. Cancer Cell. 21, 374–387 (2012).

Mainwaring, L. A. & Kenney, A. M. Divergent functions for eIF4E and S6 kinase by sonic hedgehog mitogenic signaling in the developing cerebellum. Oncogene. 30, 1784–1797 (2011).

Wu, C. C. et al. mTORC1-Mediated Inhibition of 4EBP1 Is Essential for Hedgehog Signaling-Driven Translation and Medulloblastoma. Dev Cell. 43, 673–688 e675 (2017).

Chaturvedi, N. K. et al. Improved therapy for medulloblastoma: targeting hedgehog and PI3K-mTOR signaling pathways in combination with chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 9, 16619–16633 (2018).

Buonamici, S. et al. Interfering with resistance to smoothened antagonists by inhibition of the PI3K pathway in medulloblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2, 51ra70 (2010).

Metcalfe, C. et al. PTEN loss mitigates the response of medulloblastoma to Hedgehog pathway inhibition. Cancer Res. 73, 7034–7042 (2013).

Hambardzumyan, D. et al. PI3K pathway regulates survival of cancer stem cells residing in the perivascular niche following radiation in medulloblastoma in vivo. Genes Dev. 22, 436–448 (2008).

Hartmann, W. et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/AKT signaling is activated in medulloblastoma cell proliferation and is associated with reduced expression of PTEN. Clin Cancer Res. 12, 3019–3027 (2006).

Pei, Y. et al. HDAC and PI3K Antagonists Cooperate to Inhibit Growth of MYC-Driven Medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell. 29, 311–323 (2016).

Hambardzumyan, D., Squatrito, M., Carbajal, E. & Holland, E. C. Glioma formation, cancer stem cells, and akt signaling. Stem Cell Rev. 4, 203–210 (2008).

Frasson, C. et al. Inhibition of PI3K Signalling Selectively Affects Medulloblastoma Cancer Stem Cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 973912 (2015).

Eckerdt, F. et al. Potent Antineoplastic Effects of Combined PI3Kalpha-MNK Inhibition in Medulloblastoma. Mol Cancer Res (2019).

Fruman, D. A. & Rommel, C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 13, 140–156 (2014).

Thorpe, L. M., Yuzugullu, H. & Zhao, J. J. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 15, 7–24 (2015).

Denny, W. A. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase alpha inhibitors: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 23, 789–799 (2013).

Elkabets, M. et al. mTORC1 inhibition is required for sensitivity to PI3K p110alpha inhibitors in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 5, 196ra199 (2013).

Le, X. et al. Systematic Functional Characterization of Resistance to PI3K Inhibition in Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 6, 1134–1147 (2016).

Leroy, C. et al. Activation of IGF1R/p110beta/AKT/mTOR confers resistance to alpha-specific PI3K inhibition. Breast Cancer Res. 18, 41 (2016).

Vora, S. R. et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitors sensitize PIK3CA mutant breast cancer to PI3K inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 26, 136–149 (2014).

Juric, D. et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase alpha-Selective Inhibition With Alpelisib (BYL719) in PIK3CA-Altered Solid Tumors: Results From the First-in-Human Study. J Clin Oncol. 36, 1291–1299 (2018).

Xu, J., Margol, A., Asgharzadeh, S. & Erdreich-Epstein, A. Pediatric brain tumor cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 116, 218–224 (2015).

Zhukova, N. et al. Subgroup-specific prognostic implications of TP53 mutation in medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 31, 2927–2935 (2013).

Chou, T. C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 58, 621–681 (2006).

Cho, Y. J. et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 29, 1424–1430 (2011).

Northcott, P. A. et al. Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes. Nature. 488, 49–56 (2012).

Beauchamp, E. et al. GLI1 is a direct transcriptional target of EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 284, 9074–9082 (2009).

Didiasova, M., Schaefer, L. & Wygrecka, M. Targeting GLI Transcription Factors in Cancer. Molecules. 23 (2018).

Leuchte, K. et al. Anchorage-independent growth of Ewing sarcoma cells under serum-free conditions is not associated with stem-cell like phenotype and function. Oncol Rep. 32, 845–852 (2014).

Nor, C. et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate promotes cell death and differentiation and reduces neurosphere formation in human medulloblastoma cells. Mol Neurobiol. 48, 533–543 (2013).

Pastrana, E., Silva-Vargas, V. & Doetsch, F. Eyes wide open: a critical review of sphere-formation as an assay for stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 8, 486–498 (2011).

Zanini, C. et al. Medullospheres from DAOY, UW228 and ONS-76 cells: increased stem cell population and proteomic modifications. PLoS One. 8, e63748 (2013).

Ramaswamy, V. et al. Risk stratification of childhood medulloblastoma in the molecular era: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 821–831 (2016).

Guerreiro, A. S. et al. Targeting the PI3K p110alpha isoform inhibits medulloblastoma proliferation, chemoresistance, and migration. Clin Cancer Res. 14, 6761–6769 (2008).

Ehrhardt, M. et al. The PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 displays promising in vitro and in vivo efficacy for targeted medulloblastoma therapy. Oncotarget. 6, 802–813 (2015).

Salm, F. et al. The Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase p110alpha Isoform Regulates Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor Expression via c-Myc and miR-125b to Promote Cell Proliferation in Medulloblastoma. PLoS One. 10, e0123958 (2015).

Sandberg, A. A. & Bridge, J. A. Updates on cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: Ewing sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 123, 1–26 (2000).

Zwerner, J. P. et al. The EWS/FLI1 oncogenic transcription factor deregulates GLI1. Oncogene. 27, 3282–3291 (2008).

Joo, J. et al. GLI1 is a central mediator of EWS/FLI1 signaling in Ewing tumors. PLoS One. 4, e7608 (2009).

Bell, J. B. et al. HDL nanoparticles targeting sonic hedgehog subtype medulloblastoma. Sci Rep. 8, 1211 (2018).

Eckerdt, F. et al. A simple, low-cost staining method for rapid-throughput analysis of tumor spheroids. Biotechniques. 60, 43–46 (2016).

Eckerdt, F. et al. Regulatory effects of a Mnk2-eIF4E feedback loop during mTORC1 targeting of human medulloblastoma cells. Oncotarget. 5, 8442–8451 (2014).

Bell, J. B. et al. MNK Inhibition Disrupts Mesenchymal Glioma Stem Cells and Prolongs Survival in a Mouse Model of Glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Res. 14, 984–993 (2016).

Bowman, R. L. et al. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol. 19, 139–141 (2017).

Iqbal, A. et al. Targeting of glioblastoma cell lines and glioma stem cells by combined PIM kinase and PI3K-p110alpha inhibition. Oncotarget. 7, 33192–33201 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Northwestern University’s Center for Advanced Microscopy and the Flow Cytometry Core Facility for assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-CA121192, R01-CA77816, and by grant I01CX000916 from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: F.E., J.C., J.B.B., L.C.P. Development of methodology: F.E., J.C., J.B.B., E.M.B. Acquisition of data: F.E., J.C., J.B.B., G.T.B. Analysis and interpretation of data: F.E., J.C., J.B.B., E.M.B., L.C.P. Oversight of project development: F.E., S.G., L.C.P. Writing of the manuscript: F.E., L.C.P. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eckerdt, F., Clymer, J., Bell, J.B. et al. Pharmacological mTOR targeting enhances the antineoplastic effects of selective PI3Kα inhibition in medulloblastoma. Sci Rep 9, 12822 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49299-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49299-3

This article is cited by

-

Inositol treatment inhibits medulloblastoma through suppression of epigenetic-driven metabolic adaptation

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Combined PI3Kα-mTOR Targeting of Glioma Stem Cells

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.