Abstract

We aim to evaluate whether different definitions of esophagus (DEs) impact on the esophageal toxicity prediction for esophageal cancer (EC) patients administered intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost (SIB-IMRT) vs. standard-dose IMRT (SD-IMRT). The esophagus for 21 patients diagnosed with primary EC were defined in the following four ways: the whole esophagus, including the tumor (ESOwhole); ESOwhole within the treatment field (ESOinfield); ESOinfield, excluding the tumor (ESOinfield-tumor) and ESOwhole, excluding the tumor (ESOwhole-tumor). The difference in the dose variation, acute esophageal toxicity (AET) and late esophageal toxicity (LET) of four DEs were compared. We found that the mean esophageal dose for ESOwhole, ESOinfield, ESOinfield-tumor and ESOwhole-tumor were increased by 7.2 Gy, 10.9 Gy, 4.6 Gy and 2.0 Gy, respectively, in the SIB-IMRT plans. Radiobiological models indicated that a grade ≥ 2 AET was 2.9%, 3.1%, 2.2% and 1.6% higher on average with the Kwint model and 14.6%, 13.2%, 7.2% and 3.4% higher with the Wijsman model for the four DEs. A grade ≥ 3 AET increased by 4.3%, 7.2%, 4.2% and 1.2%, respectively. Additionally, the predicted LET increased by 0.15%, 0.39%, 1.2 × 10−2% and 1.5 × 10−3%. Our study demonstrates that different DEs influence the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, an increasing number of clinical studies have demonstrated the feasibility, efficacy and safety of intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost (SIB-IMRT) for the treatment of esophageal cancer (EC), resulting in an improvement in the local-regional control and overall survival while maintaining clinically tolerated toxicities1,2,3.

Although the SIB-IMRT technique has shown encouraging outcomes for EC patients, concerns about the increased risk of esophageal toxicity with the SIB-IMRT technique are increasing. Acute esophageal toxicity (AET) and late esophageal toxicity (LET) are two common dose-limiting toxicities that will hinder the use of dose escalation in EC patients administered concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT)2, 4, 5. Unfortunately, few clinical investigations have been conducted to explore the potential risk of esophageal toxicity using SIB-IMRT vs. standard-dose IMRT (SD-IMRT). Furthermore, most of the studies on the risks of esophageal toxicity induced by IMRT and concurrent chemotherapy strategies were primarily conducted on lung cancer patients4, 6, 7. In contrast, EC patients are particularly different from lung cases because the tumor is within the esophagus, resulting in the heterogeneity of the esophagus definition when implementing the radiation therapy treatment. Therefore, whether different definitions of esophagus (DEs) influence the evaluation of the esophageal toxicity in response to SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT should be further investigated.

In this study, we aim to evaluate the impact of DEs on the dosimetric changes and esophageal toxicity prediction between the SIB-IMRT and SD-IMRT dosing strategies in EC patients using predictive models derived from clinical data.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Review Committee of Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. All methods in this study were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Considering that this is not a treatment-based study, our institutional review board waived the need for obtaining written informed consent from the participants.

Patient selection

CT simulating data sets of 21 upper thoracic esophageal cancer patients enrolled in a phase II clinical trial (Clinicaltrial.gov number, NCT01670409, and Chinese Clinical Research Registry number, ChiCTR-ONC-12002356) were used in this study.

Immobilization and simulation

The patients were immobilized in supine position with the head and shoulders wrapped in a thermoplastic mask (Guangzhou Klarity Medical & Equipment Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China). Contrast enhanced computer tomography (CT) scans of 0.5-mm slice thickness from the neck to the upper abdomen were obtained using a 16-slice CT scanner (Philips Brilliance Big Bore Oncology Configuration, Cleveland, OH) under free breathing. The CT images were subsequently delivered to the Eclipse Treatment Planning System (Version 10.0, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) by DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) 3.0 interface for target volume contouring, organs at risk (OARs) contouring and treatment planning.

Target volume and OARs delineation

We previously introduced the methods of target and OARs delineation for EC patients8. Briefly, the gross tumor volume (GTV) included the primary tumor (GTVP) and positive regional lymph nodes (GTVLN). The delineation of GTV was determined using CT images, endoscopic reports or barium swallow fluoroscopy. GTVLN included mediastinal or supraclavicular lymph nodes with the shortest axis ≥1 cm. Clinical target volume (CTV) was delineated with a 2-cm margin in the longitudinal direction and a 0.5–1.0 cm margin in the radial direction with respect to the GTVP and a 0.5-cm uniform margin from GTVLN. Paraesophageal or tracheoesophageal groove lymph nodes that did not meet the criteria of positive lymph nodes, but with their shortest axis ≥0.5 cm were also encompassed in CTV. To generate two planning target volume (PTV), PTV64.8 and PTV50.4, an isotropic 0.5-cm margin was expanded from GTV and CTV, respectively. OARs, including spinal cord and lung were generated according to the reference9. Briefly, lung contouring was limited to the air-inflated lung parenchyma without inclusion of the fluid and atelectasis visible on CT images. The proximal bronchial tree should also be excluded. Contouring of the spinal cord should start at the same cranial level as the esophagus to the bottom of L2, or the level at which the cord ended. The planning OAR volume (PRV) for the spinal cord was generated from the spinal cord expanding a 0.5-cm margin. Four types of esophagus delineation were generated to identify their dose-response differences. ESOwhole presented the whole esophagus from the level of cricoid cartilage on every CT image to the gastroesophageal junction, including the tumor6, 7, 10, 11; ESOinfield was the portion of ESOwhole within the treatment field, where the treatment field was defined as the upper and lower edges of the largest fields10; ESOinfield-tumor was the portion of ESOinfield, excluding the tumor; and ESOwhole-tumor was the portion of ESOwhole, also excluding the tumor.

Planning objectives

The following dose constraints for OARs were used: spinal cord, Dmax (maximum dose) <45 Gy; PRV for spinal cord, V50 ≤ 1 cc; lung, V5 < 60%, V10 < 50%, V20 < 30% and mean lung dose (MLD) < 15 Gy, where Vx is percentage of the target volume receiving ≥ x Gy dose. The dose was normalized to ensure that 95% of the PTV received 100% of the prescription.

Treatment planning

The prescription for the SIB-IMRT plan was set at 64.8 Gy in 28 fractions for PTV64.8 (delivered in 2.31 Gy/fraction) and 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions for PTV50.4 (delivered in 1.8 Gy/fraction)12. The prescription for the SD-IMRT plans was set at 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions (delivered in 1.8 Gy/fraction) for PTV50.4. Treatment plans were generated using five sliding window-based coplanar fields, with beam arrangements of 210°, 300°, 0°, 60° and 150°. All plans were designed using 6 MV photon beam from a TrueBeam linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Plan optimization was performed using the Dose Volume Optimizer (DVO, version 10.0.28) algorithm, selecting a maximum dose rate of 600 monitor units per minute (MU/min). The dose calculation was performed using the Anisotropic Analytical Algorithm (AAA, version 10.0.28), considering the heterogeneity correction. Several dose-limiting structures were generated to make the dose conformal to the target. We employed the base dose function (BDF) method as reported in our previous study to acquire a more homogeneous dose distribution13. Briefly, the fractions of the original plan were modified to half (from 28 to 14 in the study), and subsequently, the half-prescribed plan was copied and reoptimized using the half-prescribed plan as the base dose. After the dose was calculated, the fractions of the plan were doubled to generate the target plan.

Prediction of esophageal toxicity

We used the Kwint model to predict grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 AET7. The Kwint model derived from 139 patients after CCRT treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) shows a sigmoid-shaped relationship between grade ≥ 2 AET and V50. Moreover, the Wijsman model, which is a Lyman-Kutcher-Burman (LKB)-based predicting model generated from 149 advanced stage NSCLC patients undergoing CCRT, was also established for estimating grade ≥ 2 AET6. The following parameters were used in the Wijsman model: n = 1.04, m = 0.65 and D50 = 32.84 Gy. The Chen model is an a LKB-based predicting model derived from 171 patients NSCLC patients treated with CCRT, and we use it to predict the incidence of LET4 using the following parameters: n = 0.03, m = 0.03 and TD50 = 76.1 Gy. All physical doses were converted to a biologically equivalent dose in 2 Gy fraction (EQD2) dose to calculate the potential risk. For esophageal toxicity prediction, α/β of 10 and 3 Gy were employed to predict AET and LET, respectively. A detailed procedure of this calculation was published in our previous work14.

Statistical analysis

All data in this study were shown as the mean plus standard deviation (mean ± SD). Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Friedman Test was used to determine the difference in dosimetry and predicted toxicity among four DEs. Comparison of the sub-group data was compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The results were considered statistically significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

From September 2012 to December 2013, 21 upper thoracic esophageal cancer patients were used in this study. The age of the patients ranged from 49 to 73 years old and the other characteristics were listed in Table 1.

DEs influence dose changes for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT

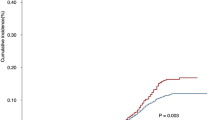

The dose differences of the four DEs were listed in Table 2. Compared with the SD-IMRT plan, different DEs resulted in similar dose increase in the SIB-IMRT plan. The increase of V30, V40 and V50 for the four DEs was comparable (p > 0.05). However, the increase of V60 and Dmean was significantly different (p < 0.05). Specifically, V60 values for the ESOwhole, ESOinfield, ESOinfield-tumor and ESOwhole-tumor were increased by 29.6 cc, 29.5 cc, 3.4 cc and 3.7 cc, respectively. Dmean for ESOwhole, ESOinfield, ESOinfield-tumor and ESOwhole-tumor were increased by 7.2 Gy, 10.9 Gy, 4.6 Gy and 2.0 Gy, respectively. However, Dmax values for the ESOwhole, ESOinfield, ESOinfield-tumor and ESOwhole-tumor were equally increased by 14.2 Gy. Compared with ESOwhole-tumor and ESOinfield-tumor, the increase of V60 and Dmean was higher for the ESOwhole and ESOinfield definitions. The dose volume histogram (DVH) for the four DEs was presented in Fig. 1. The dose variation for the four DEs in the sagittal view from one representative case was illustrated in Fig. 2.

DVH for different DEs. (A) DVH for ESOwhole, (B) DVH for ESOinfield, (C) DVH for ESOinfield-tumor and (D) DVH for ESOwhole-tumor. ESOwhole = the entire esophagus including the tumor; ESOinfield = the portion of ESOwhole within the treatment field; ESOinfield-tumor = the portion of ESOinfield, excluding the tumor; ESOwhole-tumor = the portion of ESOwhole, excluding the tumor. SIB-IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost; SD-IMRT = standard-dose intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Esophageal dose variation for four DEs. Color wash displayed the dose difference between the SIB-IMRT and SD-IMRT dosing strategies from one representative case. (A) Dose for ESOwhole (red line), (B) dose for ESOinfield (green line), (C) dose for ESOinfield-tumor (blue line), (D) dose for ESOwhole-tumor (brown line). ESOwhole = the entire esophagus, including the tumor; ESOinfield = the portion of ESOwhole within the treatment field; ESOinfield-tumor = the portion of ESOinfield excluding the tumor; ESOwhole-tumor = the portion of ESOwhole excluding the tumor. SIB-IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost; SD-IMRT = standard-dose intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

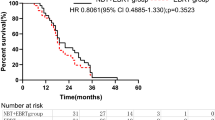

DEs impact on the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT

The esophageal toxicity prediction for the four DEs was listed in Table 3. Compared with the SD-IMRT plan, the predicted grade ≥ 2 AET values using the Kwint model in the SIB-IMRT group were 2.9%, 3.1%, 2.2% and 1.6% higher on average for ESOwhole, ESOinfield, ESOinfield-tumor and ESOwhole-tumor, respectively. Grade ≥ 2 AET predicted using the Wijsman predicting model were 14.6%, 13.2%, 7.2% and 3.4% higher on average. Additonally, the SIB-IMRT plan was also 4.3%, 7.2%, 4.2% and 1.2% higher on average for grade ≥ 3 AET. The predicted LET were increased by 0.15%, 0.39%, 1.2 × 10−2% and 1.5 × 10−3% for the four DEs. Compared with ESOwhole-tumor and ESOinfield-tumor, the increase was higher with the ESOwhole and ESOinfield definition.

Discussion

Whether different DEs influence the evaluation of the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT remains unknown. To address this issue, we employed four DEs to distinguish the changes on esophageal toxicity prediction between the SIB-IMRT and SD-IMRT dosing regimens using radiobiological models. We found that different DEs influence the esophageal toxicity prediction by up to 11.2% (grade ≥ 2 AET predicted with the Wijsman model). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the influence of different DEs on the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients received SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT.

AET and LET characterized by dysphagia, odynophagia, stenosis and perforation are common radiation-induced adverse events4, 15 that significantly affect the quality-of-life and negatively impact the long-term survival of patients when received thoracic irradiation16. Compared to AET, LET is relatively rare16. In the definitive treatment of EC patients, the esophagus is more prone to develop these symptoms because part of the esophagus is inside the treatment field, leading to high dose irradiation during treatment. Three independent studies showed that 60% of the patients developed grade ≥ 2 AET, 40% of the patients developed grade ≥ 3 AET and 22% of the patients suffered from LET when experiencing SIB-IMRT treatment2, 4, 5. Accordingly, evaluation of the incidence of esophageal toxicity is important for clinical treatment.

Although two dosimetric studies demonstrated an improved benefit of SIB-IMRT compared with the SD-IMRT strategy12, 17, no further information on esophageal toxicity was provided in the two studies. Until recently, the DEs are not consistent for EC patients. Whether the portion of esophagus outside the treatment field should be included in the toxicity prediction is unclear. Caglar et al. suggested that the in-field esophagus was a new predictor for esophagitis in NSCLC patients10. However, other studies used the entire esophagus as the predictor6, 7, 18. Interestingly, we found that two DEs (ESOwhole and ESOinfield) resulted in a similar trend of increase for esophageal toxicity prediction in the SIB-IMRT plans (Table 3), indicating that both of them are comparable for esophageal toxicity evaluation. However, we also found that the increase in esophageal toxicity using ESOwhole and ESOinfield was higher than that of the ESOwhole-tumor and ESOinfield-tumor, particularly when the Wijsman model was used (Table 3). Therefore, more attention should be paid on a consensus on the DEs during the radiation therapy treatment for EC patients.

The results of our analysis are partly dependent on the choice of radiobiological models and parameters used. To strengthen the reliability of our data, we employed two esophageal toxicity predicting models from the literature to predict the likelihood toxicity of grade ≥ 2 AET. Interestingly, we observed that two independent models exhibited a similar trend of increase in the esophageal toxicity using the SIB-IMRT technique, although the absolute values were different between the two models. Considering that both of these models were generated from more than one hundred patients experiencing clinical treatment, we propose that these data on the prediction of esophageal toxicity are reliable. However, we observed that the increase using the Wijsman model was more remarkable than that from the Kwint model. This finding might partly reflect the different chemotherapy regimens used in the two independent investigations. Only low-dose cisplatin was used in the Kwint model7, whereas gemcitabine combined with cisplatinum or etoposide combined with cisplatinum were selectively delivered according to condition of the patients in the Wijsman model6. Because AET is enhanced with CCRT19, the chemotherapy regimen might partly influence our prediction of esophageal toxicity.

A significant diversity of predictors used for AET prediction have been reported in previous studies. Dose volume parameters, such as V30, V40, V50, V60, Dmax and mean esophagus dose were reported to enable AET prediction15, 18, 20,21,22. Palma et al. performed a meta-analysis enrolling the largest population to date (1082 patients) to show that V60 emerged as the best predictor of grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 radiation-induced esophagitis with good calibration and discrimination21. The results indicated that the high dose region might principally contribute to the formation of esophageal toxicity. From this perspective, we infer that it is more reasonble to use ESOwhole and ESOinfield, which include the GTV for esophageal toxicity prediction. However, further clinical validation studies are warranted to confirm our speculation. Recently, Wang et al. used a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to analyze the predictive values of three methods of lung definitions for radiation pneumonitis (RP)23. The authors concluded that the definition of lungs-GTV (lung subtracts GTV) might be the most accurate definition for predicting RP. We have completed a phase II study implementing the SIB-IMRT strategy combined with chemotherapy for EC patients3, and more accurate DE is expected after analyzing the clinical data using the ROC method.

In the past few years, many studies have developed many dosimetric parameters to predict the occurrence of grade ≥ 2 or grade ≥ 3 AET20,21,22; however, only several studies have developed models to predict their incidence6, 7, 18, 24. Furthermore, two independent studies have proposed models to predict the incidence of grade ≥ 2 or grade ≥ 3 esophagitis; unfortunately, both studies were conducted using 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3DCRT) technique11, 18, 24, 25. Because IMRT has been reported as superior in delivering a more conformal dose and improving normal tissue sparing compared with 3DCRT26, 27, the models generated from 3DCRT might potentially limit the evaluation of AET for patients undergoing IMRT treatment. To date, AET predicting models derived from patients undergoing IMRT and chemotherapy treatment are scarce except for the Kwint and Wijsman models. Consistent with this information, we used these models for esophageal toxicity prediction in the study.

Although our study has demonstrated that different DEs influence the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT dosing strategies, there are some limitations. (1) The sample size of our study was a bit small to fully distinguish the changes in dosimetry and esophageal toxicity between the SIB-IMRT and SD-IMRT dosing strategies. Thus, a larger patient cohort is needed for further validation in the clinic. (2) We employed the esophagitis-predicting models from lung cancer patients, but the applicability and feasibility of these models should to be further validated. (3) Notably, only the Kwint model was used to predict grade ≥ 3 AET which might partially weaken the reliability of our results. However, to the best of our knowledge, the Kwint model is the only grade ≥ 3 AET-predicting model derived from IMRT and chemotherapy practices, and this model should be used it for prediction.

We must state that AET and LET is dose relavent. With standard dose, SIB-IMRT strategy for EC patients was reportly feasible without increasing AET or LET at neoadjuvant and adjuvant CCRT settings28, 29.

Conclusions

In summary, our study demonstrated that different DEs influence the esophageal toxicity prediction for EC patients administered SIB-IMRT vs. SD-IMRT. Our results require further validation in clinical samples.

References

Yu, W. W. et al. Simultaneous integrated boost intensity-modulated radiotherapy in esophageal carcinoma: early results of a phase II study. Strahlenther Onkol. 190, 979–986 (2014).

Yu, W. et al. Safety of dose escalation by simultaneous integrated boosting radiation dose within the primary tumor guided by (18)FDG-PET/CT for esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 114, 195–200 (2015).

Chen, J. et al. Radiation dose escalation by simultaneous modulated accelerated radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy for esophageal cancer: a phase II study. Oncotarget. 7, 22711–22719 (2016).

Chen, C. et al. Severe late esophagus toxicity in NSCLC patients treated with IMRT and concurrent chemotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 108, 337–341 (2013).

Roeder, F. et al. Intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with concurrent chemotherapy as definitive treatment of locally advanced esophageal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 9, 191 (2014).

Wijsman, R. et al. Multivariable normal-tissue complication modeling of acute esophageal toxicity in advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with intensity-modulated (chemo-)radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 117, 49–54 (2015).

Kwint, M. et al. Acute esophagus toxicity in lung cancer patients after intensity modulated radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 84, e223–228 (2012).

Zhang, W. Z. et al. Simultaneous modulated accelerated radiation therapy for esophageal cancer: a feasibility study. World J Gastroenterol. 20, 13973–13980 (2014).

Kong, F. M. et al. Consideration of dose limits for organs at risk of thoracic radiotherapy: atlas for lung, proximal bronchial tree, esophagus, spinal cord, ribs, and brachial plexus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 81, 1442–1457 (2011).

Caglar, H. B., Othus, M. & Allen, A. M. Esophagus in-field: a new predictor for esophagitis. Radiother Oncol. 97, 48–53 (2010).

Zehentmayr, F. et al. Normal tissue complication models for clinically relevant acute esophagitis (>/=grade 2) in patients treated with dose differentiated accelerated radiotherapy (DART-bid). Radiat Oncol. 10, 121 (2015).

Welsh, J. et al. Esophageal cancer dose escalation using a simultaneous integrated boost technique. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 82, 468–474 (2012).

Lu, J. Y. et al. Improving target coverage and organ-at-risk sparing in intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical oesophageal cancer using a simple optimisation method. PLoS One. 10, e0121679 (2015).

Huang, B. T. et al. Radiobiological modeling analysis of the optimal fraction scheme in patients with peripheral non-small cell lung cancer undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy. Sci Rep. 5, 18010 (2015).

Rose, J., Rodrigues, G., Yaremko, B., Lock, M. & D’Souza, D. Systematic review of dose-volume parameters in the prediction of esophagitis in thoracic radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 91, 282–287 (2009).

Bar-Ad, V., Ohri, N. & Werner-Wasik, M. Esophagitis, treatment-related toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 7, 31–35 (2012).

Warren, S. et al. Radiobiological determination of dose escalation and normal tissue toxicity in definitive chemoradiation therapy for esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 90, 423–429 (2014).

Zhu, J. et al. Analysis of acute radiation-induced esophagitis in non-small-cell lung cancer patients using the Lyman NTCP model. Radiother Oncol. 97, 449–454 (2010).

Auperin, A. et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 28, 2181–2190 (2010).

Zhang, Z. et al. Risk factors of radiation-induced acute esophagitis in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 9, 54 (2014).

Palma, D. A. et al. Predicting esophagitis after chemoradiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 87, 690–696 (2013).

Uyterlinde, W. et al. Prognostic parameters for acute esophagus toxicity in intensity modulated radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 107, 392–397 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. Differences and radiation pneumonitis prediction of lung dosimetric parameters based on three normal lung definitions in 3DCRT treatment planning. Chinese Journal of Radiation Oncology. 23, 396–400 (2014).

Huang, E. X. et al. Modeling the risk of radiation-induced acute esophagitis for combined Washington University and RTOG trial 93-11 lung cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 82, 1674–1679 (2012).

Gomez, D. R. et al. Predictors of high-grade esophagitis after definitive three-dimensional conformal therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, or proton beam therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 84, 1010–1016 (2012).

Chandra, A. et al. Feasibility of using intensity-modulated radiotherapy to improve lung sparing in treatment planning for distal esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 77, 247–253 (2005).

Fenkell, L. et al. Dosimetric comparison of IMRT vs. 3D conformal radiotherapy in the treatment of cancer of the cervical esophagus. Radiother Oncol. 89, 287–291 (2008).

Zeng, M. et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost based dose escalation on neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced distal esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 8, 474–480 (2016).

Yaremko, B. P. et al. Adjuvant concurrent chemoradiation using intensity-modulated radiotherapy and simultaneous integrated boost for resected high-risk adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction. Radiat Oncol. 8, 33 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81602667), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2016ZC0166), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2015534), Shantou University Medical College Clinical Research Enhancement Initiative (201424), The Creative and Facilitating Program of Shantou University, Collaborative and Creative Center, Molecular Diagnosis and Personalized Medicine, Shantou University, Guangdong Province, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.-T.H. and C.-Z.C. conceived and designed the experiments. R.-H.H., W.-Z.Z., L.-J.G., L.-Y.X. and J.-Z.C. performed the experiments. B.-T.H., R.-H.H., W.-Z.Z. and L.-J.G. collected the data. P.-X.L. analyzed the data. B.-T.H. wrote the paper. D.-R.L., W.L. and C.-Z.C. revised the paper. All authors have reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Bt., Huang, Rh., Zhang, Wz. et al. Different definitions of esophagus influence esophageal toxicity prediction for esophageal cancer patients administered simultaneous integrated boost versus standard-dose radiation therapy. Sci Rep 7, 120 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00168-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00168-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.