Abstract

Genetic diversity is lost in small and isolated populations, affecting many globally declining species. Interspecific admixture events can increase genetic variation in the recipient species’ gene pool, but empirical examples of species-wide restoration of genetic diversity by admixture are lacking. Here we present multi-fold coverage genomic data from three ancient Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) approximately 2,000–4,000 years old and show a continuous or recurrent process of interspecies admixture with the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) that increased modern Iberian lynx genetic diversity above that occurring millennia ago despite its recent demographic decline. Our results add to the accumulating evidence for natural admixture and introgression among closely related species and show that this can result in an increase of species-wide genetic diversity in highly genetically eroded species. The strict avoidance of interspecific sources in current genetic restoration measures needs to be carefully reconsidered, particularly in cases where no conspecific source population exists.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Merged and R1 and R2 reads sequence data are available for download at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) repository under study number PRJEB58855. Other data files supporting the results can be downloaded at figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24512722 (structure and diversity analyses) and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24486640 (admixture analyses).

Code Availability

Scripts used for diversity, structure and admixture analyses are available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24512722 (structure and diversity analyses) and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24486640 (admixture analyses).

References

Allendorf, F. W., Funk, W. C., Aitken, S. N., Byrne, M. & Luikart, G. Conservation and the Genomics of Populations 3rd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Frankham, R., Ballou, J. D. & Briscoe, D. A. Introduction to Conservation Genetics 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

de Bruyn, M., Hoelzel, A. R., Carvalho, G. R. & Hofreiter, M. Faunal histories from Holocene ancient DNA. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 405–413 (2011).

Diez-del-Molino, D., Sanchez-Barreiro, F., Barnes, I., Gilbert, M. T. P. & Dalen, L. Quantifying temporal genomic erosion in endangered species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 176–185 (2018).

Hofreiter, M. & Barnes, I. Diversity lost: are all Holarctic large mammal species just relict populations? BMC Biol. 8, 46 (2010).

Leigh, D. M., Hendry, A. P., Vázquez-Domínguez, E. & Friesen, V. L. Estimated six per cent loss of genetic variation in wild populations since the industrial revolution. Evol. Appl. 12, 1505–1512 (2019).

Ralls, K. et al. Call for a paradigm shift in the genetic management of fragmented populations. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12412 (2018).

Barlow, A. et al. Partial genomic survival of cave bears in living brown bears. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1563–1570 (2018).

Iacolina, L., Corlatti, L., Buzan, E., Safner, T. & Sprem, N. Hybridisation in European ungulates: an overview of the current status, causes, and consequences. Mamm. Rev. 49, 45–59 (2019).

Kumar, V. et al. The evolutionary history of bears is characterized by gene flow across species. Sci. Rep. 7, 46487 (2017).

Li, G., Davis, B. W., Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae). Genome Res. 26, 1–11 (2016).

Palkopoulou, E. et al. A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E2566–E2574 (2018).

Chan, W. Y., Hoffmann, A. A. & van Oppen, M. J. H. Hybridization as a conservation management tool. Conserv. Lett. 12, e12652 (2019).

Quilodrán, C. S., Montoya-Burgos, J. I. & Currat, M. Harmonizing hybridization dissonance in conservation. Commun. Biol. 3, 391 (2020).

Corbet, G. B. & Hill, J. E. A World List of Mammalian Species 2nd edn (British Museum of Natural History, 1986).

Tumlison, R. Felis lynx. Mamm. Species 269, 1–8 (1987).

Weigel, I. Das Fellmuster der wildlebenden Katzenarten und der Hauskatze in vergleichender und stammesgeschichtlicher Hinsicht Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen (München, 1961).

Van den Brink, F.-H. Distribution and speciation of some carnivores. Mamm. Rev. 1, 67–79 (1970).

Kurten, B. & Granqvist, E. Fossil pardel lynx (Lynx pardina spelaea Boule) from a cave in southern France. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 24, 39–43 (1987).

Matjuschkin E. N. Der Luchs (A. Ziemsen Verlag, 1978).

Werdelin, L. The evolution of lynxes. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 18, 37–71 (1981).

Harris, A., Foley, N., Williams, T. & Murphy, W. Tree house explorer: a novel genome browser for phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac130 (2022).

Li, G., Figueiró, H. V., Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. Recombination-aware phylogenomics reveals the structured genomic landscape of hybridizing cat species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 2111–2126 (2019).

Casas-Marcé, M. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of genetic variation in the Iberian lynx along its path to extinction reconstructed with ancient DNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2893–2907 (2017).

Abascal, F. et al. Extreme genomic erosion after recurrent demographic bottlenecks in the highly endangered Iberian lynx. Genome Biol. 17, 251 (2016).

Korlević, P. et al. Reducing microbial and human contamination in DNA extractions from ancient bones and teeth. BioTechniques 59, 87–93 (2015).

Bazzicalupo, E. et al. History, demography and genetic status of Balkan and Caucasian Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) populations revealed by genome-wide variation. Divers. Distrib. 28, 65–82 (2022).

Lucena-Perez, M. et al. Genomic patterns in the widespread Eurasian lynx shaped by late quaternary climatic fluctuations and anthropogenic impacts. Mol. Ecol. 29, 812–828 (2020).

Lucena-Perez, M. et al. Ancient genome provides insights into the history of Eurasian lynx in Iberia and Western Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 285, 107518 (2022).

Kleinman-Ruiz, D. et al. Purging of deleterious burden in the endangered Iberian lynx. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2110614119 (2022).

Lucena-Perez, M. et al. Bottleneck-associated changes in the genomic landscape of genetic diversity in wild lynx populations. Evol. Appl. 14, 2664–2679 (2021).

D’Elia, J., Haig, S. M., Mullins, T. D. & Miller, M. P. Ancient DNA reveals substantial genetic diversity in the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) prior to a population bottleneck. Condor 118, 703–714 (2016).

Dufresnes, C. et al. Howling from the past: historical phylogeography and diversity losses in European grey wolves. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20181148 (2018).

Dussex, N., von Seth, J., Robertson, B. C. & Dalen, L. Full mitogenomes in the critically endangered kakapo reveal major post-glacial and anthropogenic effects on neutral genetic diversity. Genes 9, 220 (2018).

Feng, S. et al. The genomic footprints of the fall and recovery of the crested ibis. Curr. Biol. 29, 340–349.e347 (2019).

Sánchez-Barreiro, F. et al. Historical population declines prompted significant genomic erosion in the northern and southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). Mol. Ecol. 30, 6355–6369 (2021).

Sheng, G. L. et al. Ancient DNA from giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) of south-western China reveals genetic diversity loss during the Holocene. Genes 9, 198 (2018).

van der Valk, T., Diez-del-Molino, D., Marques-Bonet, T., Guschanski, K. & Dalen, L. Historical genomes reveal the genomic consequences of recent population decline in eastern gorillas. Curr. Biol. 29, 165–170 e6 (2019).

Vila, C. et al. Rescue of a severely bottlenecked wolf (Canis lupus) population by a single immigrant. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 270, 91–97 (2003).

Clavero, M. & Delibes, M. Using historical accounts to set conservation baselines: the case of lynx species in Spain. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 1691–1702 (2013).

Jiménez, J., Clavero, M. & Reig-Ferrer, A. New old news on the ‘lobo cerval’ (Lynx lynx?) in NE Spain. Galemys 30, 1–6 (2018).

Mecozzi, B. et al. The tale of a short-tailed cat: new outstanding late Pleistocene fossils of Lynx pardinus from southern Italy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 262, 107028 (2021).

Rodríguez-Varela, R. et al. Ancient DNA reveals past existence of Eurasian lynx in Spain. J. Zool. 298, 94–102 (2016).

Rodríguez-Varela, R. et al. Ancient DNA evidence of Iberian lynx palaeoendemism. Quat. Sci. Rev. 112, 172–180 (2015).

Bell, D. A. et al. The exciting potential and remaining uncertainties of genetic rescue. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 1070–1079 (2019).

Tallmon, D. A., Luikart, G. & Waples, R. S. The alluring simplicity and complex reality of genetic rescue. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 489–496 (2004).

Whiteley, A. R., Fitzpatrick, S. W., Funk, W. C. & Tallmon, D. A. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 42–49 (2015).

Detry, C. & Arruda, A. M. A fauna da Idade do Ferro e da Época Romana de Monte Molião (Lagos, Algarve): continuidades e rupturas na dieta alimentar. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia 16, 213–226 (2013).

Fulton T. L. in Ancient DNA: Methods and Protocols (eds Shapiro B. & Hofreiter M.) (Humana, 2012).

Dabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15758–15763 (2013).

Gansauge, M. T. & Meyer, M. Single-stranded DNA library preparation for the sequencing of ancient or damaged DNA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 737–748 (2013).

Dabney, J. & Meyer, M. Length and GC-biases during sequencing library amplification: a comparison of various polymerase-buffer systems with ancient and modern DNA sequencing libraries. BioTechniques 52, 87–94 (2012).

Preseq software. Smith Lab Research https://github.com/smithlabcode/preseq (2014).

FastQC software. Babraham Bioinformatics https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (2010).

SeqPrep software. John St. John https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep (2016).

Buckley, R. et al. A new domestic cat genome assembly based on long sequence reads empowers feline genomic medicine and identifies a novel gene for dwarfism. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008926 (2020).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Picard software. Broad Institute https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard (2014).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Jónsson, H., Ginolhac, A., Schubert, M., Johnson, P. L. F. & Orlando, L. mapDamage2.0: fast approximate Bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 29, 1682–1684 (2013).

Sheng, G.-L. et al. Paleogenome reveals genetic contribution of extinct giant panda to extant populations. Curr. Biol. 29, 1695–1700 e6 (2019).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Estimation of allele frequency and association mapping using next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinf. 12, 231 (2011).

Li, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27, 2987–2993 (2011).

Fumagalli, M. Assessing the effect of sequencing depth and sample size in population genetics inferences. PLoS One 8, e79667 (2013).

Fumagalli, M., Vieira, F. G., Linderoth, T. & Nielsen, R. ngsTools: methods for population genetics analyses from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 30, 1486–1487 (2014).

Chrom-Compare software. Paleogenomics https://github.com/Paleogenomics/Chrom-Compare (2014).

Borg I. & Groenen P. J. F. Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications (Springer, 1997).

Martin, A. D., Quinn, K. M. & Park, J. H. MCMCpack: Markov chain Monte Carlo in R. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–21 (2011).

R_Core_Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Skotte, L., Korneliussen, T. S. & Albrechtsen, A. Estimating individual admixture proportions from next generation sequencing data. Genetics 195, 693–702 (2013).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Kopelman, N. M., Mayzel, J., Jakobsson, M., Rosenberg, N. A. & Mayrose, I. Clumpak: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 1179–1191 (2015).

Korneliussen, T. S., Albrechtsen, A. & Nielsen, R. ANGSD: analysis of next generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinf. 15, 356 (2014).

Korneliussen, T. S., Moltke, I., Albrechtsen, A. & Nielsen, R. Calculation of Tajima’s D and other neutrality test statistics from low depth next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinf. 14, 289 (2013).

Canty A. & Ripley B. boot: bootstrap R (S-Plus) functions. R package version 1.3–11 (2014).

Durand, E. Y., Patterson, N., Reich, D. & Slatkin, M. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2239–2252 (2011).

Green, R. E. et al. A draft sequence of the neandertal genome. Science 328, 710–722 (2010).

Gunther, T. & Nettelblad, C. The presence and impact of reference bias on population genomic studies of prehistoric human populations. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008302 (2019).

Barlow, A., Hartmann, S., González, J., Hofreiter, M. & Paijmans, J. Consensify: a method for generating pseudohaploid genome sequences from palaeogenomic datasets with reduced error rates. Genes 11, 50 (2020).

Consensify software. Barlow, A. and Paijmans, J.L.A. https://github.com/jlapaijmans/Consensify (2018).

Admixture workflow. Cahill, J.A. https://github.com/jacahill/Admixture (2018).

Pease, J. B. & Hahn, M. W. Detection and polarization of introgression in a five-taxon phylogeny. Syst. Biol. 64, 651–662 (2015).

Page, A. J. et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb. Genom. 2, e000056 (2016).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

TreeHacker software. Paijmans, J.L.A and Barlow, A. https://github.com/jlapaijmans/treehacker (2023).

Rodríguez, A. & Delibes, M. Internal structure and patterns of contraction in the geographic range of the Iberian lynx. Ecography 25, 314–328 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Spanish Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica through projects CGL2013-47755-P and CGL2017-84641-P to J.A.G and is an extension of a project on ancient lynx genetics granted to Miguel Delibes de Castro by the Fundación BBVA. M.L.-P. was supported by a PhD contract from Programa Internacional de Becas ‘La Caixa-Severo Ochoa’. J.N. received financial support through projects HAR2014- 55131 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and SGR2014-108 from the Generalitat de Catalunya. We acknowledge support from Science for Life Laboratory, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the National Genomics Infrastructure funded by the Swedish Research Council and Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science for assistance with massively parallel sequencing and access to the UPPMAX computational infrastructure. We also acknowledge the support of the Supercomputing Wales project, which is part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund via the Welsh Government. Logistical support was provided by the Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular certified to ISO9001:2015 and ISO14001:2015 quality and environmental management systems. Data processing and most calculations and analyses were carried out in the Genomics servers of Doñana’s Singular Scientific-Technical Infrastructure, with additional computing and storage resources provided by Fundación Pública Galega, Centro Tecnolóxico de Supercomputación de Galicia. Logistical laboratory support was provided by the Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular certified to ISO9001:2015 and ISO14001:2015 quality and environmental management systems. Data processing and most calculations and analyses were carried out in the Genomics servers of Doñana’s Singular Scientific-Technical Infrastructure, with additional computing and storage resources provided by Fundación Pública Galega Centro Tecnolóxico de Supercomputación de Galicia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.G. conceived the project. A.B., J.A.G. and M.L.-P. designed the study. C.D., F.N. and J.N. provided ancient samples and critical input on archaeological context. M.L.-P. performed the laboratory work under the supervision of J.L.A.P. and M.H. A.B., J.L.A.P. and M.L.-P. analysed the data. A.B., J.A.G., J.L.A.P. and M.L.-P. interpreted the results, with critical input from M.H. and L.D. M.L.-P. drafted the manuscript with support from A.B. and J.A.G. and input by J.L.A.P., C.D., J.N., M.H. and L.D. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Eduardo Eizirik and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Authentication of ancient DNA data using MapDamage.

On the left, cytosine deamination patterns. X axis indicates the relative nucleotide position of the reads. Plots show the proportion of T where the reference genome possesses a C (red) and proportion of A where the reference possesses a G (blue). Increased C to T substitutions towards the ends of the read are typical damage patterns for ancient data, although the single-stranded library preparation with UDG (uracil–DNA glycosylase) treatment reduced this pattern. Plot on the right represents the fragment length distribution. Minimum read length for mapping used was 30 bp, resulting in a truncation of the plot.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Additional clustering analyses results.

Alternative clustering patterns obtained in five runs of NGSadmix for K = 4 and K = 5. Population names on top, with number of samples within parentheses.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Genetic diversity in ancient and contemporary populations.

Diversity of the ancient population (n = 3) and different random subsamples (n = 3) of individuals from the contemporary populations, Andújar and Doñana, considering both transitions and transversions (a) and transversion only (b). Points represent the mean and bars, although not always visible, and represent the standard deviation calculated over 10 kb windows using 100 iterations.

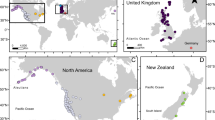

Extended Data Fig. 4 D statistics calculated for tree topologies relating different genome trios.

On the left, the different tree topologies tested (a–g). IL= Iberian lynx, EL= Eurasian lynx. Western EL included genomes sampled in Kirov, Caucasus, Balkans and Carpathians, while Eastern EL genomes were sampled in Primorsky Krai and Yakutia. All topologies were tested using the domestic cat as the outgroup. Red and white points show significant and non-significant D values, respectively. The seven different tree topologies tested (a–g) are displayed for each category of D values shown, with double-headed arrows indicating the admixing lineages supported by significant tests. a shows similar introgression in different contemporary IL individuals. b and c show similar and non-significant d-stat when different eastern and western Eurasian lynx individuals are compared. d and e show higher admixture signal from contemporary Eurasian lynx than from a single ancient Eurasian lynx from the Iberian Peninsula, whereas ancient Iberian lynx is less admixed with ancient EL than contemporary Western EL (F) and similarly than Eastern EL (G).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Results of phylogenetic tests of gene flow direction.

The schematic at the top of the figure shows topologies informative on gene flow from Eurasian into Iberian lynx. An excess of genomic windows returning topologies where the ancient Iberian lynx is in a basal position relative to the number of genomic windows retuning topologies where the contemporary Iberian lynx is basal indicates gene flow from Eurasian lynx onto the modern Iberian lynx population, above that occurring into the ancient Iberian lynx population. The lower part of the figure shows individual results (points) generated using each combination of one contemporary Iberian lynx (30 individuals total) and one of the two Eurasian lynx as representative for the two main Eurasian clades. An excess (mean 1.84-fold higher) of topologies with the ancient Iberian lynx in the basal position in all comparisons indicates that the admixture inferred using D statistics can be attributed, at least in part, to gene flow from Eurasian lynx into ancestors of contemporary Eurasian lynx.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lucena-Perez, M., Paijmans, J.L.A., Nocete, F. et al. Recent increase in species-wide diversity after interspecies introgression in the highly endangered Iberian lynx. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 282–292 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02267-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02267-7