Abstract

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) now represents 20–25% of all ‘breast cancers’ consequent upon detection by population-based breast cancer screening programmes. Currently, all DCIS lesions are treated, and treatment comprises either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery supplemented with radiotherapy. However, most DCIS lesions remain indolent. Difficulty in discerning harmless lesions from potentially invasive ones can lead to overtreatment of this condition in many patients. To counter overtreatment and to transform clinical practice, a global, comprehensive and multidisciplinary collaboration is required. Here we review the incidence of DCIS, the perception of risk for developing invasive breast cancer, the current treatment options and the known molecular aspects of progression. Further research is needed to gain new insights for improved diagnosis and management of DCIS, and this is integrated in the PRECISION (PREvent ductal Carcinoma In Situ Invasive Overtreatment Now) initiative. This international effort will seek to determine which DCISs require treatment and prevent the consequences of overtreatment on the lives of many women affected by DCIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) was rarely diagnosed before the advent of breast screening, yet it now accounts for 25% of detected ‘breast cancers’. Over 60,000 women are diagnosed with DCIS each year in the USA,1,2 >7000 in the UK3 and >2500 in the Netherlands.4 DCIS is a proliferation of neoplastic luminal cells that are confined to the ductolobular system of the breast. If DCIS progresses to invasive breast cancer, DCIS cells penetrate the ductal basement membrane and invade the surrounding parenchyma. Individual lesions differ in aspects of the disease: presentation, histology, progression, and genetic features.5,6 Despite being pre- or non-invasive, DCIS is often regarded as an early form of (Stage 0) breast cancer. Therefore, conventional management includes mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery supplemented with radiotherapy; in some countries, adjuvant endocrine therapy is added. Regrettably, current therapeutic approaches result in overtreatment of some women with DCIS (Box 1). The Marmot Report in 2012 recognised the burden of overtreatment to women’s wellbeing.7 In effect, women with DCIS are labelled as ‘cancer patients’, with concomitant anxiety and negative impact on their lives, despite the fact that most DCIS lesions will probably never progress to invasive breast cancer. Owing to the uncertainty regarding which lesions run the risk of progression to invasive cancer, current risk perceptions are misleading and consequently bias the dialogue between clinicians and women diagnosed with DCIS, resulting in overtreatment for some, and potentially many, women.

Improving the management and treatment of DCIS presents a central challenge: distinguishing indolent, harmless DCIS lesions from potentially hazardous ones. This poses a fundamental question to address: ‘Is cancer always cancer?’. To answer this question, we need to adopt an interdisciplinary and translational approach, merging fields of epidemiology, molecular biology, clinical research and psychosocial studies. How low does the risk need to be to refrain from treating DCIS? What are the prognostic markers and read-outs we can rely on? How do we frame and communicate the risks involved?

In this review, we describe the current approaches to diagnosing DCIS, the perception of the risk of developing invasive breast carcinoma, the treatment options available following a diagnosis and a current knowledge of the progression of DCIS, before outlining future endeavours and the need for an integrated approach that blends clinical and patient insights with scientific advances.

DCIS incidence

The number of women diagnosed with DCIS over the past few decades largely follows the introduction of population-based breast cancer screening.8,9,10,11,12 The European standardised rate of in situ lesions has increased four-fold, from 4.90 per 100,000 women in 1989 (accounting for 4.5% of all diagnoses registered as breast cancer) to 20.68 in 2011 (accounting for 12.8% of all diagnoses registered as breast cancer; www.cijfersoverkanker.nl). Of all in situ breast lesions reported, 80% are DCIS.12,13 Nevertheless, the incidence of mortality from early-stage breast cancer has not decreased concurrently with DCIS detection and treatment, indicating that managing DCIS does not reduce breast-cancer-specific mortality and therefore could be considered as overtreatment.8,11 A review of autopsies in women of all ages revealed a median prevalence of 8.9% (range 0–14.7%). For woman aged >40 years, this prevalence was 7–39%,14 whereas breast cancer is diagnosed in only 1% of women in the same age range.13 These data suggest that a large number of women might have an undetected source of DCIS that will never become symptomatic.

Current diagnosis and imaging

DCIS is usually straightforward to detect by mammography because of its association with calcifications; the proliferation of cells itself is not visible on the mammogram. However, as only 75% of all DCIS lesions contain calcifications,15 a substantial percentage of DCIS lesions will not be detected by mammography, implying that some lesions might be mammographically occult or that the diameter of the area containing calcifications underestimates the extent of DCIS.16,17 This suggests that DCIS might be left behind following breast-conserving treatment in a proportion of cases.

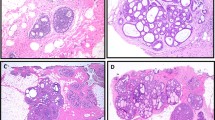

After detection, the lesion is classified by the pathologist by histological features as low, medium or high grade, which is assumed to correspond to the level of aggressiveness. Surprisingly, many grading systems exist.18 An agreement on classification was reached during a consensus meeting in the USA where consensus was reached to include nuclear grade, presence of necrosis, cell polarisation and architectural patterns in the pathology report.19,20 Some studies showed a slight tendency for high-grade DCIS to progress to invasive breast cancer,21 but others demonstrated that grade is not significantly associated with the risk of local invasive recurrence.22,23 Greater consistency in grading could result in more certainty about the association of morphology with progression and outcome. In addition, as grade is not a perfect discriminator for progression risk, other risk discriminators, such as molecular biomarkers, are examined (discussed later in ‘Molecular, cellular and microenvironmental aspects’).

Perception of risk

Generally, patients diagnosed with DCIS have an excellent long-term breast-cancer-specific survival of around 98% after 10 years of follow-up24,25,26,27 and a normal life expectancy.27 However, a consensus in the medical community is lacking on how to effectively communicate to patients about DCIS and the associated risk of development into invasive cancer.28 It is essential to be aware of the fact that if the lower-grade DCIS (considered as the lower-risk lesions) progresses into invasive breast cancer, this will often be the lower-grade, slow-growing and early-detectable invasive disease, with excellent prognosis.

Because both diagnosis and treatment of the condition can have a profound psychosocial impact on a woman’s life, adequate perception of risk by both health professionals and patients is important in determining the appropriate modalities of treatment. Despite an excellent prognosis and normal life-expectancy, women diagnosed with DCIS experience stress and anxiety.29 Studies report that most women with DCIS (and early-stage breast cancer) have little knowledge and inaccurate perceptions of the risk of disease progression, and this misperception is associated with psychological distress.30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Women with DCIS make substantial changes to their behaviour after diagnosis, including smoking cessation and decreasing the use of postmenopausal hormones.37

Similar to progression rates for DCIS, classic lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) confers a risk of 1–2% per year to develop into invasive disease.38,39 First-line treatment for LCIS usually comprises active surveillance; unlike DCIS, doctors and patients accept the concept of active surveillance to monitor for progression of LCIS before administering any aggressive treatment. The need for effective doctor–patient communication is therefore essential for patients to understand the risk of recurrence.40,41 According to Kim et al.,36 women in whom DCIS was detected experienced high decisional conflict in treatment options and were not satisfied with the information provided to them. The development of a prediction tool could help to classify patients into risk groups and provide accurate guidance to patients, as well as healthcare professionals, in their choice of an appropriate treatment option.42 Nowadays, such a tool is even more important, as patients increasingly wish to engage in shared decision making about their disease.

Treatment of DCIS

Surgery and radiation therapy

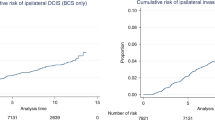

Currently, breast-conserving treatment for DCIS is frequently recommended. A mastectomy is advised if the DCIS is too extensive to allow breast conservation.43 According to Thompson et al.,21 the recurrence rates (for both invasive and in situ) with 5 years median follow-up are 0.8% after mastectomy, 4.1% after breast-conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy and 7.2% after breast-conserving surgery alone. According to Elshof et al.,22 invasive recurrence rates are 1.9, 8.8 and 15.4%, respectively, after 10 years median follow-up. The 15-year cumulative incidence in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project 17 (NSABP17) trial of patients with clear margins is 19.4% after breast-conserving surgery alone and 8.9% after breast-conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy.44 Four randomised clinical trials have been performed to investigate the role of radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for DCIS after complete local excision of the lesion. In a meta-analysis, these trials show a 50% reduction in the risk of local recurrences (for both in situ and invasive) after radiotherapy.45 Radiotherapy was reported to be effective in reducing the risk of local recurrence in all analysed subgroups according to age, clinical presentation, grade and type of DCIS.

Adding radiotherapy to breast-conserving treatment reduces local recurrence rates but does not influence overall survival or breast-cancer-specific survival.27,45,46 The added value of conducting a sentinel node biopsy procedure is uncertain. In general, such a procedure is done with mastectomy for DCIS (since there is no opportunity to perform a subsequent sentinel node biopsy) or where there is a high suspicion for invasive disease even where DCIS alone is present in the preoperative biopsy.47,48

A recent study based on an analysis of data from the American Cancer Registry of >100,000 women diagnosed with DCIS suggests that aggressive treatment might not be necessary to save lives.24,49 A retrospective Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study demonstrated for the first time that patients with low-grade DCIS had the same overall survival and breast-cancer-specific survival rates with or without surgery.49 These findings prompted the breast healthcare community to explore innovative studies that could circumvent the need for harsh therapeutic intervention for treating an indolent condition.24,49

Endocrine therapy

Owing to the side effects of hormonal therapy and ambiguous results from clinical trials, postmenopausal women with DCIS are rarely treated with endocrine therapy in many countries. In addition, the notion of systemic treatment for a localised disease with an excellent outcome is perceived as being counterintuitive.21,50 Two randomised clinical trials have investigated the role of tamoxifen – a drug that inhibits the oestrogen receptor (ER) – versus placebo in DCIS.44,51 The risk of subsequent invasive ipsilateral breast cancer was found to be reduced by tamoxifen in the NSABP trial44; the UK, Australia and New Zealand (UK/ANZ) DCIS trial demonstrated a reduction in recurrent DCIS but not in invasive breast cancer.51 Tamoxifen administration did not influence overall survival in either trial52 and appeared to be more effective at reducing the incidence of new breast events in patients who did not receive radiotherapy in the NSABP trial.51 Yet, a non-significant reduction in the incidence of new breast events was seen in the prospective series from the UK, independent of whether the patients received radiotherapy or not.53 Furthermore, to prevent one recurrence, 15 patients would need to be treated (the number needed to treat).52 In terms of efficacy, tamoxifen and anastrozole (an aromatase inhibitor) are comparable, and the percentage of women who reported side effects were 91% and 93% for anastrozole and tamoxifen, respectively. Although anastrozole administration more often causes side effects such as musculoskeletal pain, hypercholesterolaemia and strokes, tamoxifen is associated with muscle spasm, deep vein thrombosis and the development of gynaecological symptoms and gynaecological cancers.54 In the USA, the uptake of endocrine treatment is higher than in other countries, and nearly half of all ER positive patients are treated by additional adjuvant tamoxifen treatment, indicating a lack of consensus on the added value of this treatment.55

Active surveillance

To address the question whether some patients with DCIS are overtreated, a group of patients not treated with conventional therapies should be studied. A prospective study with long-term follow-up is the only way to gain confidence regarding the natural course of DCIS, and therefore the potential need for interventions. Recently, three clinical trials (LORIS (United Kingdom, NCT02766881),56 COMET (United States of America, NCT02926911)57,58 and LORD (The Netherlands, NCT02492607))59 have opened to randomise patients with low-risk DCIS between active surveillance and standard treatment. Lower grades of DCIS are enrolled (grade 1 and/or grade 2 with limitations depending on the trial). Patients receive annual mammography (in COMET biannual mammography) in the active surveillance arm to monitor the lesions. Patients in the control arm will get conventional treatment (surgery often supplemented with radiotherapy). The primary outcome assesses whether active surveillance is non-inferior to surgery in terms of ipsilateral invasive breast-cancer-free survival56 (LORIS), ipsilateral invasive breast-cancer-free percentage at 2 years (COMET)57 or at 10 years (LORD).59 Because the primary outcomes of the trials are based on the occurrence of invasive disease during follow-up, it is essential to exclude an invasive component at the time of enrolment. Missed invasive disease at DCIS diagnosis is reported up to 26%.60 However, Grimm et al. found that, among trial-eligible patients, there was upstaging of 6, 7 and 10% for COMET, LORIS and LORD trials, respectively, compared with a general upstaging of 17% at the time of surgery for preoperatively diagnosed DCIS of all types.61 All trials include only pure DCIS with the use of multiple biopsies, additional biopsies in extended lesions and vacuum-assisted (large volume) biopsies.

From DCIS to invasive breast cancer

Proposed mechanisms for the development of invasive breast cancer

Although the natural course of the intraductal process is unknown, DCIS is considered to be a non-obligate precursor of invasive breast cancer. Four evolutionary models have been proposed to describe the progression of DCIS into invasive breast cancer (Fig. 1).

The first model is the independent lineage model. On the basis of mathematical simulations of the observed frequencies of the histological grade of DCIS and the histological grade of invasive disease in the same biopsy sample, Sontag et al. proposed that in situ and invasive cell populations arise from different cell lineages and develop in parallel and independently of each other.62,63,64 In support of this theory, Narod et al.65 state that small clusters of cancer cells with metastatic ability spread concomitantly through various routes to different organs and can therefore give rise to DCIS, invasive breast cancer and metastatic deposits simultaneously. Recent studies elucidating molecular differences between DCIS and invasive breast cancer further support the relevance of this model.66

The convergent phenotype model proposes that different genotypes of DCIS could lead to invasive breast cancer of the same phenotype. Furthermore, this model assumes that all the cells within the DCIS duct have the same genetic aberrations but that the combination of aberrations could differ between ducts (within the same DCIS lesion).67,68 Hernandez et al. demonstrated similarity in the genomic profiles of DCIS and invasive breast cancer in the majority of the matched pairs. However, in some cases, DCIS and adjacent invasive breast cancer differ in copy number and gene mutations, supporting the notion that, at least in some cases, progression is driven by specific clones leading to the same phenotype.69

In the evolutionary bottleneck model, individual cells within a duct are considered to accumulate different genetic aberrations; however, only a subpopulation of cells with a specific genetic profile is able to overcome an evolutionary bottleneck and invade into the adjacent tissue.63,64,68 This bottleneck model is supported by studies that report high genetic concordance between in situ and invasive lesions in addition to some differences between DCIS and invasive disease.70

In the multiclonal invasion model, multiple clones have the ability to escape from the ducts and co-migrate into the adjacent tissues to establish invasive carcinomas63,64 Casasent et al. demonstrated, using single-cell sequencing, that most mutations and copy number aberrations evolved within the ducts prior to the process of invasion. Shifts in clonal frequencies were observed, suggesting that some genotypes are more invasive than others. The same subclones were present in both in situ and in invasive regions with no additional copy number aberrations acquired during invasion and few invasion-specific mutations. These findings are, however, limited by their small sample size and comparison of contemporaneous DCIS and invasive disease.63

These putative models illustrate the potential complexity of the invasion process in DCIS and indicate that indolent lesions might become invasive via a combination of more than one of the proposed mechanisms.6

Molecular, cellular and microenvironmental aspects

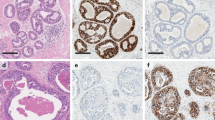

Many studies have focussed on identifying molecular markers of the invasive process and recent studies69,70,71,72 have linked mutations in PIK3CA, TP53 and GATA3 genes with aggressive DCIS; TP53 mutations were reported to be exclusively associated with high-grade DCIS.71,72 However, the requirement for fresh tissue and large amounts of DNA for whole-exome or genome sequencing has limited the extent of studies for determining the landscape of genetic mutations in DCIS.

Some molecular analyses have shown that pre-invasive lesions and invasive breast cancer display remarkably similar patterns,73,74,75,76 indicating a common ancestor77; other groups have found that progression from DCIS to invasive breast cancer might be driven by a subset of cells with specific genetic aberrations, implying contribution to tumour initiation.66,77,78,79,80 PAM50 is a gene signature that can classify invasive breast cancer into five intrinsic subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, basal-like and normal-like), which adds prognostic and predictive information.81 Lesurf et al.74 applied the PAM50 signatures to DCIS and showed substantial differences between the subtypes, indicating that each PAM50 subtype undergoes a distinct evolutionary course of disease progression. Strikingly, their results showed that these properties, specific for the PAM50 subtypes, reflect changes that involve the microenvironment rather than molecular changes specific for epithelial cells. This supports increasing evidence for the role of the microenvironment in tumour progression and disease outcome more generally.74 Alcazar et al.82 demonstrated a switch to a less active tumour immune environment during the in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition and identified immune regulators and genomic alterations that shape tumour evolution. Their data suggest that the levels of activated CD8+ T cells might predict which DCIS is likely to progress to invasive disease.82 In patients with invasive breast cancer – particularly those with triple-negative and HER2-positive subtypes – the presence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), especially higher numbers of CD8+ cells, together with fewer FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, is associated with a better outcome.83

One of the key molecular differences between DCIS and invasive breast cancer is the prevalence of HER2 amplification: 34% for DCIS84 versus 13% for invasive disease.85 HER2 amplification might be a prognostic factor in predicting an in situ recurrence after DCIS, but it seems not to be predictive for an invasive recurrence.86 That said, one study with a long follow-up (mean follow-up >15 years) counterintuitively demonstrated that HER2 positivity in primary DCIS was associated with a lower risk of late invasive breast cancer compared with HER2 negativity.87 In HER2-positive DCIS, TILs are present at higher levels, but an association with an invasive recurrence risk after DCIS has not been reported.

A caveat of molecular studies on DCIS is the fact that most studies examine relatively small series of DCIS lesions with a contemporaneously adjacent invasive component, instead of a metachronous (subsequent) invasive lesion developing during follow-up. Thus these series are inherently biased, because the majority of the DCIS lesions will never develop an invasive component. In addition, most studies do not distinguish between in situ or invasive recurrences after DCIS. Two biomarker-based assays have been developed for DCIS,88,89 which purport to predict the benefit of radiotherapy for DCIS. However, the assays only discriminate between the risk of an in situ versus an invasive recurrence after DCIS to a limited extent. This difference is important for the women involved, especially regarding treatment choices, prognosis and psychosocial impact. Furthermore, intratumoural heterogeneity complicates our understanding of the relationship between DCIS and its invasive counterpart, as most studies only analyse a small proportion of an often heterogeneous lesion or analyse a bulk tissue sample in which small cell populations are easily overlooked.64 The low number of samples and lack of longitudinal follow-up data mean that our overall molecular knowledge of the landscape of changes in DCIS is limited.

Looking ahead

Uncertainty exists about how DCIS develops, and global consensus is lacking as to how best to optimally manage this disease. A better understanding of the biology of DCIS and the natural course of the disease is required to support patients and healthcare professionals in making more informed treatment decisions, in turn reducing the current overtreatment of DCIS. In 2014, Gierisch et al.90 described and prioritised knowledge gaps of patients and decision makers with regards to future research of DCIS for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), a private, non-governmental, non-profit, USA-based institute created by The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 to ‘help people make informed healthcare decisions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes’. By reviewing the existing literature and using a forced-ranking prioritisation method, a list of ten evidence gaps was created (Table 1). Issues that needed immediate attention include the effective communication of information about diagnosis and prognosis and dedicated efforts to fill the knowledge gaps regarding long-term implications and risks of a diagnosis of DCIS.90

To address these priorities in DCIS, a multidisciplinary approach with scientific, clinical and patient expertise is needed. Data from large retrospective cohorts should be integrated with in vitro and in vivo studies and the results should be validated to transform clinical practise. To fund such a large multinational consortium, Cancer Research UK and the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) partnered to support the Grand Challenge91 award in 2017, the PREvent ductal Carcinoma In Situ Invasive Overtreatment Now (PRECISION) initiative (see Box 2 and Supplementary Material for more information about PRECISION).

Conclusion

Current perceptions of the risk-framing dialogue between clinicians and women diagnosed with DCIS are currently resulting in the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS. The need to reframe perceptions of risk and to avoid overtreatment is urgent, as overtreatment leads to physical and emotional harm for patients and to unnecessary costs for society. Specifically, knowing when a lesion could be or will not be life-threatening requires a thorough understanding of the progression and evolution of DCIS. To this end, initiatives, such as PRECISION, have been set out to reduce the burden of overtreatment of DCIS by gaining deep knowledge about the biology of DCIS. This knowledge will contribute to informed decision-making between patients and clinicians, without compromising the excellent outcomes for DCIS that are presently achieved. Dealing with this challenge demands an integrated approach that blends clinical and patient insights with scientific advances in order to improve the diagnosis, treatment and management of DCIS. To accomplish this, it is critical that patient advocates, scientists and clinicians work together, exemplified by a collaborative patient advocate and scientist in the PRECISION research team video: https://youtu.be/aoGSDDto1Gc.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 7–30 (2018).

American Cancer Society (2017). https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf.

Cancer Research UK (2017). http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/incidence-in-situ.

Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation. Online available: www.cijfersoverkanker.nl (Accessed 8 July 2016).

Bane, A. Ductal carcinoma in situ: what the pathologist needs to know and why. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2013, 914053 (2013).

Gorringe, K. L. & Fox, S. B. Ductal carcinoma in situ biology, biomarkers, and diagnosis. Front Oncol 7, 248 (2017).

Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 380, P1778–P1786 (2012).

Bleyer, A. & Welch, H. G. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1998–2005 (2012).

Bluekens, A. M., Holland, R., Karssemeijer, N., Broeders, M. J. & den Heeten, G. J. Comparison of digital screening mammography and screen-film mammography in the early detection of clinically relevant cancers: a multicenter study. Radiology 265, 707–714 (2012).

Ernster, V. L., Ballard-Barbash, R., Barlow, W. E., Zheng, Y., Weaver, D. L., Cutter, G. et al. Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in women undergoing screening mammography. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94, 1546–1554 (2002).

Esserman, L. J., Thompson, I. M. Jr. & Reid, B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. JAMA 310, 797–798 (2013).

Kuerer, H. M., Albarracin, C. T., Yang, W. T., Cardiff, R. D., Brewster, A. M., Symmans, W. F. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: state of the science and roadmap to advance the field. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 279–288 (2009).

Siziopikou, K. P. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: current concepts and future directions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 137, 462–466 (2013).

Welch, H. G. & Black, W. C. Using autopsy series to estimate the disease ‘reservoir’ for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: how much more breast cancer can we find? Ann. Intern. Med. 127, 1023–1028 (1997).

Barreau, B., De Mascarel, I., Feuga, C., MacGrogan, G., Dilhuydy, M. H., Picot, V. et al. Mammography of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: Review of 909 cases with radiographic-pathologic correlations. Eur. J. Radiol. 54, 55–61 (2005).

Holland, R., Hendriks, J. H., Vebeek, A. L., Mravunac, M. & Schuurmans Stekhoven, J. H. Extent, distribution, and mammographic/histological correlations of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Lancet 335, 519–522 (1990).

Thomas, J., Hanby, A., Pinder, S. E., Ball, G., Lawrence, G., Maxwell, A. et al. Adverse surgical outcomes in screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Eur. J. Cancer 50, 1880–1890 (2014).

Pinder, S. E., Duggan, C., Ellis, I. O., Cuzick, J., Forbes, J. F., Bishop, H. et al. A new pathological system for grading DCIS with improved prediction of local recurrence: results from the UKCCCR/ANZ DCIS trial. Br. J. Cancer 103, 94–100 (2010).

Consensus Conference on the classification of ductal carcinoma in situ. The Consensus Conference Committee. Cancer 80, 1798–1802 (1997).

Schnitt, S. J. & Collins, L. C. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, 2013.

Thompson, A. M., Clements, K., Cheung, S., Pinder, S. E., Lawrence, G., Sawyer, E. et al. Management and 5-year outcomes in 9938 women with screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ: the UK Sloane Project On behalf of the Sloane Project Steering Group (NHS Prospective Study of Screen-Detected Non-invasive Neoplasias) 1. Eur. J. Cancer 101, 210–219 (2018).

Elshof, L. E., Schaapveld, M., Schmidt, M. K., Rutgers, E. J., van Leeuwen, F. E. & Wesseling, J. Subsequent risk of ipsilateral and contralateral invasive breast cancer after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: incidence and the effect of radiotherapy in a population-based cohort of 10,090 women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 159, 553–563 (2016).

Bijker, N., Peterse, J. L., Duchateau, L., Julien, J. P., Fentiman, I. S., Duval, C. et al. Risk factors for recurrence and metastasis after breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10853. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 2263–2271 (2001).

Worni, M., Akushevich, I., Greenup, R., Sarma, D., Ryser, M. D., Myers, E. R. et al. Trends in treatment patterns and outcomes for ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, djv263 (2015).

Morrow, M. & Katz, S. J. Addressing overtreatment in DCIS: what should physicians do now? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, djv290 (2015).

Fisher, E. R., Dignam, J., Tan-Chiu, E., Costantino, J., Fisher, B., Paik, S. et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer 86, 429–438 (1999).

Elshof, L. E., Schmidt, M. K., Rutgers, E. J. T., van Leeuwen, F. E., Wesseling, J. & Schaapveld, M. Cause-specific mortality in a population-based cohort of 9799 women treated for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann. Surg. 267, 952–958 (2017).

Fallowfield, L., Matthews, L., Francis, A., Jenkins, V. & Rea, D. Low grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): how best to describe it? Breast 23, 693–696 (2014).

Ganz, P. A. Quality-of-life issues in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 218–222 (2010).

Hawley, S. T., Janz, N. K., Griffith, K. A., Jagsi, R., Friese, C. R., Kurian, A. W. et al. Recurrence risk perception and quality of life following treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 161, 557–565 (2017).

Ruddy, K. J., Meyer, M. E., Giobbie-Hurder, A., Emmons, K. M., Weeks, J. C., Winer, E. P. et al. Long-term risk perceptions of women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Oncologist 18, 362–368 (2013).

Liu, Y., Pérez, M., Schootman, M., Aft, R. L., Gillanders, W. E., Ellis, M. J. et al. A longitudinal study of factors associated with perceived risk of recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early-stage invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 124, 835–844 (2010).

van Gestel, Y. R. B. M., Voogd, A. C., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., Mols, F., Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P., van Driel, O. J. R. et al. A comparison of quality of life, disease impact and risk perception in women with invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur. J. Cancer 43, 549–556 (2007).

Partridge, A., Adloff, K., Blood, E., Dees, E. C., Kaelin, C., Golshan, M. et al. Risk perceptions and psychosocial outcomes of women with ductal carcinoma in situ: longitudinal results from a cohort study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 243–251 (2008).

Davey, C., White, V., Warne, C., Kitchen, P., Villanueva, E. & Erbas, B. Understanding a ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis: patient views and surgeon descriptions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 20, 776–784 (2011).

Kim, C., Liang, L., Wright, F. C., Hong, N. J. L., Groot, G., Helyer, L. et al. Interventions are needed to support patient–provider decision-making for DCIS: a scoping review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 168, 1–14 (2017).

Sprague, B. L., Trentham-Dietz, A., Nichols, H. B., Hampton, J. M. & Newcomb, P. A. Change in lifestyle behaviors and medication use after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 124, 487–495 (2010).

Lakhani, S. R., Audretsch, W., Cleton-Jensen, A. M., Cutuli, B., Ellis, I., Eusebi, V. et al. The management of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Is LCIS the same as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)? Eur. J. Cancer 42, 2205–2211 (2006).

Ottesen, G. L., Graversen, H. P., Blichert-Toft, M., Christensen, I. J. & Andersen, J. A. Carcinoma in situ of the female breast. 10 year follow-up results of a prospective nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 62, 197–210 (2000).

Janz, N. K., Li, Y., Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Jagsi, R., Kurian, A. W., An, L. C. et al. The impact of doctor–patient communication on patients’ perceptions of their risk of breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 161, 525–535 (2017).

Lee, K. L., Janz, N. K., Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Jagsi, R., Wallner, L. P., Kurian, A. W. et al. What factors influence women’s perceptions of their systemic recurrence risk after breast cancer treatment? Med. Decis. Making 38, 95–106 (2018).

Martínez-Pérez, C., Turnbull, A. K., Ekatah, G. E., Arthur, L. M., Sims, A. H., Thomas, J. S. et al. Current treatment trends and the need for better predictive tools in the management of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer Treat. Rev. 55, 163–172 (2017).

Bijker, N., Donker, M., Wesseling, J., den Heeten, G. J., Rutgers, E. J. Is DCIS breast cancer, and how do I treat it? Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 14, 75–87 (2013).

Wapnir, I. L., Dignam, J. J., Fisher, B., Mamounas, E. P., Anderson, S. J., Julian, T. B. et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103, 478–488 (2011).

Correa, C., McGale, P., Taylor, C., Wang, Y., Clarke, M., Davies, C. et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 162–177 (2010).

Corradini, S., Pazos, M., Schönecker, S., Reitz, D., Niyazi, M., Ganswindt, U. et al. Role of postoperative radiotherapy in reducing ipsilateral recurrence in DCIS: an observational study of 1048 cases. Radiat. Oncol. 13, 1–9 (2018).

van Roozendaal, L. M., Goorts, B., Klinkert, M., Keymeulen, K. B. M. I., De Vries, B., Strobbe, L. J. A. et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy can be omitted in DCIS patients treated with breast conserving therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 156, 517–525 (2016).

Ansari, B., Ogston, S. A., Purdie, C. A., Adamson, D. J., Brown, D. C. & Thompson, A. M. Meta-analysis of sentinel node biopsy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Br. J. Surg. 95, 547–554 (2008).

Narod, S. A., Iqbal, J., Giannakeas, V., Sopik, V. & Sun, P. Breast cancer mortality after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol. 1, 888–896 (2015).

Yarnold, J. Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guideline 2009. Clin. Oncol. 21, 159–160 (2009).

Cuzick, J., Sestak, I., Pinder, S. E., Ellis, I. O., Forsyth, S., Bundred, N. J. et al. Effect of tamoxifen and radiotherapy in women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ: long-term results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Lancet Oncol. 12, 21–29 (2011).

Staley, H., McCallum, I. & Bruce, J. Postoperative Tamoxifen for ductal carcinoma in situ: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 23, 546–551 (2014).

Maxwell, A. J., Clements, K., Hilton, B., Dodwell, D. J., Evans, A., Kearins, O., et al. Risk factors for the development of invasive cancer in unresected ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 44, 429–435 (2018).

Forbes, J. F., Sestak, I., Howell, A., Bonanni, B., Bundred, N., Levy, C. et al. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen for the prevention of locoregional and contralateral breast cancer in postmenopausal women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ (IBIS-II DCIS): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387, 866–873 (2016).

Ward, E. M., DeSantis, C. E., Lin, C. C., Kramer, J. L., Jemal, A., Kohler, B. et al. Cancer statistics: breast cancer in situ. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 481–495 (2015).

Francis, A., Thomas, J., Fallowfield, L., Wallis, M., Bartlett, J. M., Brookes, C. et al. Addressing overtreatment of screen detected DCIS; the LORIS trial. Eur. J. Cancer 51, 2296–2303 (2015).

Comparison of operative versus medical endocrine therapy for low risk DCIS: the COMET Trial. http://www.pcori.org/research-results/2016/comparison-operative-versus-medical-endocrine-therapy-low-risk-dcis-comet.

Hwang, E. S., Hyslop, T., Lynch, T., Frank, E., Pinto, D., Basila, D. et al. The COMET (Comparison of Operative to Monitoring and Endocrine Therapy) Trial: a phase III randomized trial for low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). BMJ Open 9, e026797 (2019).

Elshof, L. E., Tryfonidis, K., Slaets, L., van Leeuwen-Stok, A. E., Skinner, V. P., Dif, N. et al. Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ - The LORD study. Eur. J. Cancer 51, 1497–1510 (2015).

Brennan, M. E., Turner, R. M., Ciatto, S., Marinovich, M. L., French, J. R., Macaskill, P. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ at core-needle biopsy: meta-analysis of underestimation and predictors of invasive breast cancer. Radiology 260, 119–128 (2011).

Grimm, L. J., Ryser, M. D., Partridge, A. H., Thompson, A. M., Thomas, J. S., Wesseling, J., et al. Surgical upstaging rates for vacuum assisted biopsy proven DCIS: implications for active surveillance trials. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24, 3534–3540 (2017).

Sontag, L. & Axelrod, D. E. Evaluation of pathways for progression of heterogeneous breast tumors. J. Theor. Biol. 232, 179–189 (2005).

Casasent, A. K., Schalck, A., Gao, R., Sei, E., Long, A., Pangburn, W., et al. Multiclonal invasion in breast tumors identified by topographic single cell sequencing. Cell 172, 205.e12–217.e12 (2018).

Casasent, A. K., Edgerton, M. & Navin, N. E. Genome evolution in ductal carcinoma in situ: invasion of the clones. J. Pathol. 241, 208–218 (2017).

Narod, S. A. & Sopik, V. Is invasion a necessary step for metastases in breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 169, 9–23 (2018).

Yates, L. R., Gerstung, M., Knappskog, S., Desmedt, C., Gundem, G., Van Loo, P. et al. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat. Med. 21, 751–759 (2015).

Ashworth, A., Lord, C. J. & Reis-Filho, J. S. Erratum: Genetic interactions in cancer progression and treatment. Cell 145, 30–38 (2011).

Cowell, C. F., Weigelt, B., Sakr, R. A., Ng, C. K. Y., Hicks, J., King, T. A. et al. Progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer: revisited. Mol. Oncol. 7, 859–869 (2013).

Hernandez, L., Wilkerson, P. M., Lambros, M. B., Campion-Flora, A., Rodrigues, D. N., Gauthier, A. et al. Genomic and mutational profiling of ductal carcinomas in situ and matched adjacent invasive breast cancers reveals intra-tumour genetic heterogeneity and clonal selection. J. Pathol. 227, 42–52 (2012).

Kim, S. Y., Jung, S.-H., Kim, M. S., Baek, I.-P., Lee, S. H., Kim, T.-M. et al. Genomic differences between pure ductal carcinoma in situ and synchronous ductal carcinoma in situ with invasive breast cancer. Oncotarget 6, 7597–7607 (2015).

Abba, M. C., Gong, T., Lu, Y., Lee, J., Zhong, Y., Lacunza, E. et al. A molecular portrait of high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 75, 3980–3990 (2015).

Pang, J.-M. B., Savas, P., Fellowes, A. P., Mir Arnau, G., Kader, T., Vedururu, R. et al. Breast ductal carcinoma in situ carry mutational driver events representative of invasive breast cancer. Mod. Pathol. 30, 952–963 (2017).

Heselmeyer-Haddad, K., Berroa Garcia, L. Y., Bradley, A., Ortiz-Melendez, C., Lee, W. J., Christensen, R. et al. Single-cell genetic analysis of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer reveals enormous tumor heterogeneity yet conserved genomic imbalances and gain of MYC during progression. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 1807–1822 (2012).

Lesurf, R., Aure, M. R. R., Mork, H. H., Vitelli, V., Oslo Breast Cancer Research, C., Lundgren, S. et al. Molecular features of subtype-specific progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer. Cell Rep. 16, 1166–1179 (2016).

Miron, A., Varadi, M., Carrasco, D., Li, H., Luongo, L., Kim, H. J. et al. PIK3CA mutations in in situ and invasive breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 70, 5674–5678 (2010).

Pape-Zambito, D., Jiang, Z., Wu, H., Devarajan, K., Slater, C. M., Cai, K. Q. et al. Identifying a highly-aggressive DCIS subgroup by studying intra-individual DCIS heterogeneity among invasive breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE 9, e100488 (2014).

Sinha, V. C. & Piwnica-Worms, H. Intratumoral heterogeneity in ductal carcinoma in situ: chaos and consequence. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 23, 191–205 (2018).

Carraro, D. M., Elias, E. V. & Andrade, V. P. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: morphological and molecular features implicated in progression. Biosci. Rep. 34, e00090 (2014).

Landau, D. A., Carter, S. L., Stojanov, P., McKenna, A., Stevenson, K., Lawrence, M. S. et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell 152, 714–726 (2013).

Morris, L. G., Riaz, N., Desrichard, A., Senbabaoglu, Y., Hakimi, A. A., Makarov, V. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of intratumor heterogeneity as a prognostic determinant of survival. Oncotarget 7, 10051–10063 (2016).

Parker, J. S., Mullins, M., Cheang, M. C. U., Leung, S., Voduc, D., Vickery, T. et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1160–1167 (2009).

Gil Del Alcazar, C. R., Huh, S. J., Ekram, M. B., Trinh, A., Liu, L. L., Beca, F. et al. Immune escape in breast cancer during in situ to invasive carcinoma transition. Cancer Discov. 7, 1098–1115 (2017).

Savas, P., Salgado, R., Denkert, C., Sotiriou, C., Darcy, P. K., Smyth, M. J. et al. Clinical relevance of host immunity in breast cancer: from TILs to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 228–241 (2016).

Latta, E. K., Tjan, S., Parkes, R. K. & O’Malley, F. P. The role of HER2/neu overexpression/amplification in the progression of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma of the breast. Mod. Pathol. 15, 1318–1325 (2002).

Purdie, C. A., Baker, L., Ashfield, A., Chatterjee, S., Jordan, L. B., Quinlan, P. et al. Increased mortality in HER2 positive, oestrogen receptor positive invasive breast cancer: a population-based study. Br. J. Cancer 103, 475–481 (2010).

Gorringe, K. L., Hunter, S. M., Pang, J.-M., Opeskin, K., Hill, P., Rowley, S. M. et al. Copy number analysis of ductal carcinoma in situ with and without recurrence. Mod. Pathol. 28, 1174–1184 (2015).

Borgquist, S., Zhou, W., Jirström, K., Amini, R.-M., Sollie, T., Sørlie, T. et al. The prognostic role of HER2 expression in ductal breast carcinoma in situ (DCIS); a population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer 15, 468 (2015).

Bremer, T., Whitworth, P. W., Patel, R., Savala, J., Barry, T., Lyle, S., et al. A biological signature for breast ductal carcinoma in situ to predict radiation therapy (RT) benefit and assess recurrence risk. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 5895–5901 (2018).

Rakovitch, E., Nofech-Mozes, S., Hanna, W., Sutradhar, R., Baehner, F. L., Miller, D. P. et al. Multigene expression assay and benefit of radiotherapy after breast conservation in ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109, 1–8 (2017).

Gierisch, J. M., Myers, E. R., Schmit, K. M., Crowley, M. J., McCrory, D. C., Chatterjee, R. et al. Prioritization of research addressing management strategies for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann. Intern. Med. 160, 484–491 (2014).

Cancer Research UK. Grand Challenges. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/funding-for-researchers/how-we-deliver-research/grand-challenge-award.

Bluman, L. G., Borstelmann, N. A., Rimer, B. K., Iglehart, J. D. & Winer, E. P. Knowledge, satisfaction, and perceived cancer risk among women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Womens Heal Gend. Based Med. 10, 589–598 (2001).

Partridge, A. H., Elmore, J. G., Saslow, D., Mccaskill-stevens, W. & Schnitt, S. J. Challenges in ductal carcinoma in situ risk communication and decision-making report from an American Cancer Society and National Cancer Institute Workshop. CA Cancer J. Clin. 62, 203–210 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the input of PRECISION’s patient advocates: Hilary Stobart, Maggie, Wilcox, Donna Pinto, Deborah Collar, Marja van Oirsouw, and Ellen Verschuur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

E.L., J.W., J.L. and A.T. designed and wrote the manuscript. M.v.S. contributed to the revision and drafted Fig. 1. A.T., S.N.-Z., A.F., E.S.H., E.V., J.J. and D.R. revised the sections in their expertise. J.W. supervised and finalised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

The PRECISION Team is recipient of a Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge Award 2017, jointly funded by Cancer Research UK and the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Seijen, M., Lips, E.H., Thompson, A.M. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Br J Cancer 121, 285–292 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0478-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0478-6

This article is cited by

-

Progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer: molecular features and clinical significance

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

-

Long-term follow up of alemtuzumab-treated patients: a retrospective study in a Belgian tertiary care center

Acta Neurologica Belgica (2024)

-

The effects of contemporary treatment of DCIS on the risk of developing an ipsilateral invasive Breast cancer (iIBC) in the Dutch population

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2024)

-

Disparities in DCIS

Current Breast Cancer Reports (2024)

-

Oncological safety of active surveillance for low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ — a systematic review and meta-analysis

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2023)