Abstract

Background

Inequity in neonatology may be potentiated within neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) by the effects of bias. Addressing bias can lead to improved, more equitable care. Understanding perceptions of bias can inform targeted interventions to reduce the impact of bias. We conducted a mixed methods study to characterize the perceptions of bias among NICU staff.

Methods

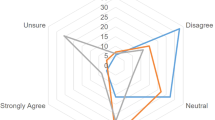

Surveys were distributed to all staff (N = 245) in a single academic Level IV NICU. Respondents rated the impact of bias on their own and others’ behaviors on 5-point Likert scales and answered one open-ended question. Kruskal–Wallis test (KWT) and Levene’s test were used for quantitative analysis and thematic analysis was used for qualitative analysis.

Results

We received 178 responses. More respondents agreed that bias had a greater impact on others’ vs. their own behaviors (KWT p < 0.05). Respondents agreed that behaviors were influenced more by implicit than explicit biases (KWT p < 0.05). Qualitative analysis resulted in nine unique themes.

Conclusions

Staff perceive a high impact of bias across different domains with increased perceived impact of implicit vs. explicit bias. Staff perceive a greater impact of others’ biases vs. their own. Mixed methods studies can help identify unique, unit-responsive approaches to reduce bias.

Impact

-

Healthcare staff have awareness of bias and its impact on their behaviors with patients, families, and staff.

-

Healthcare staff believe that implicit bias impacts their behaviors more than explicit bias, and that they have less bias than others.

-

Healthcare staff have ideas for strategies and approaches to mitigate the impact of bias.

-

Mixed method studies are effective ways of understanding environment-specific perceptions of bias, and contextual assets and barriers when creating interventions to reduce bias and improve equity.

-

Generating interventions to reduce the impact of bias in healthcare requires a context-specific understanding of perceptions of bias among staff.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 14 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $18.50 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sigurdson, K. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 144, e20183114 (2019).

Murosko, D., Passerella, M. & Lorch, S. Racial segregation and intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants. Pediatrics 145, e20191508 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in human milk Intake at neonatal intensive care unit discharge among very low birth weight infants in California. J. Pediatr. 218, 49–56.e3 (2020).

Parker, M. G. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mother’s milk feeding for very low birth weight infants in Massachusetts. J. Pediatr. 204, 134–141.e1 (2019).

Boghossian, N. S. et al. Racial and ethnic differences over time in outcomes of infants born less than 30 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics 144, e20191106 (2019).

Profit, J. et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics 140, e20170918 (2017).

Edwards, E. M. et al. Quality of care in US NICUs by race and ethnicity. Pediatrics 148, e2020037622 (2021).

Fraiman, Y. S., Stewart, J. E. & Litt, J. S. Race, language, and neighborhood predict high-risk preterm Infant Follow Up Program participation. J. Perinatol. 42, 217–222 (2022).

Sigurdson, K. et al. Former NICU families describe gaps in family-centered care. Qual. Health Res. 30, 1861–1875 (2020).

Martin, A. E., D’Agostino, J. A., Passarella, M. & Lorch, S. A. Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care. J. Perinatol. 36, 1001–1007 (2016).

Sigurdson, K., Morton, C., Mitchell, B. & Profit, J. Disparities in NICU quality of care: a qualitative study of family and clinician accounts. J. Perinatol. 38, 600–607 (2018).

Miquel-Verges, F., Donohue, P. K. & Boss, R. D. Discharge of infants from NICU to Latino families with limited English proficiency. J. Immigr. Minor Health 13, 309–314 (2011).

Nieblas-Bedolla, E., Christophers, B., Nkinsi, N. T., Schumann, P. D. & Stein, E. Changing how race is portrayed in medical education: recommendations from medical students. Acad. Med. 95, 1802–1806 (2020).

U.S. Department of Justice. Community relations services toolkit for policing: understanding bias: a resource guide bias policing overview and resource guide. https://www.justice.gov/file/1437326/download.

Phelan, S. et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 1201–1208 (2014).

Hall, W. J. et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 105, e60–e76 (2015).

Maina, I. W., Belton, T. D., Ginzberg, S., Singh, A. & Johnson, T. J. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc. Sci. Med. 199, 219–229 (2018).

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R. & Oliver, M. N. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4296–4301 (2016).

Johnson, T. J. et al. The impact of cognitive stressors in the emergency department on physician implicit racial bias. Acad. Emerg. Med. 23, 297–305 (2016).

Dyrbye, L. et al. Association of racial bias with burnout among resident physicians. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e197457 (2019).

Profit, J. et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23, 806–813 (2014).

Schnierle, J., Christian-Brathwaite, N. & Louisias, M. Implicit bias: what every pediatrician should know about the effect of bias on health and future directions. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 49, 34–44 (2019).

Hagiwara, N. et al. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc. Sci. Med. 87, 123–131 (2013).

Hagiwara, N., Slatcher, R. B., Eggly, S. & Penner, L. A. Physician racial bias and word use during racially discordant medical interactions. Health Commun. 32, 401–408 (2017).

Cooper, L. A. et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am. J. Public Health 102, 979–987 (2012).

Blair, I. V. et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann. Fam. Med. 11, 43–52 (2013).

Orchard, J. & Price, J. County-level racial prejudice and the black-white gap in infant health outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 181, 191–198 (2017).

Shapiro, N., Wachtel, E. V., Bailey, S. M. & Espiritu, M. M. Implicit physician biases in periviability counseling. J. Pediatr. 197, 109–115.e1 (2018).

Stone, J. & Moskowitz, G. B. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: What can be done to reduce it? Med. Educ. 45, 768–776 (2011).

Perdomo, J. et al. Health equity rounds: an interdisciplinary case conference to address implicit bias and structural racism for faculty and trainees. MedEdPORTAL 15, 10858 (2019).

Stone, J., Moskowitz, G. B., Zestcott, C. A. & Wolsiefer, K. J. Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma Health 5, 94–103 (2020).

Leslie, K. et al. Changes in medical student implicit attitudes following a health equity curricular intervention. Med. Teach. 40, 372–378 (2018).

Devine, P., Forscher, P., Austin, A. & Cox, W. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1267–1278 (2012).

Trent, M., Dooley, D. G. & Dougé, J. Section on Adolescent Health; Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Adolescence The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics 144, e20191765 (2019).

Reichman, V., Brachio, S. S., Madu, C. R., Montoya-Williams, D. & Peña, M. M. Using rising tides to lift all boats: equity-focused quality improvement as a tool to reduce neonatal health disparities. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 26, 101198 (2021).

Austin, Z. & Sutton, J. Qualitative research: getting started. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 67, 436–440 (2014).

FitzGerald, C. & Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 18, 19 (2017).

Roiek, A. E. et al. Differences in narrative language in evaluations of medical students by gender and under-represented minority status. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 684–691. (2019).

Palepu, A. et al. Minority faculty in academic rank in medicine. JAMA 280, 767–771 (1998).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 95, 103208 (2019).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Hahn, A., Judd, C., Hirsh, H. & Blair, I. Awareness of implicit attitudes. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143, 1369–1392 (2014).

Hahn, A. & Gawronski, B. Facing one’s implicit biases: from awareness to acknowledgment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116, 769–794 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the respondents to our survey without whom this work would not be possible. We acknowledge Isabelle Smith for the initial review and editing of survey responses to maintain anonymity.

Funding

Y.S.F. was supported by AHRQ grant number T32HS000063 as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.F. conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, completed all analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.C.C. participated in the qualitative analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. K.T.L., and A.R.H., and D.M. designed the data collection instruments, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Individuals provided implied written consent by returning the completed optional surveys. No additional consent was required by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fraiman, Y.S., Cheston, C.C., Morales, D. et al. A mixed methods study of perceptions of bias among neonatal intensive care unit staff. Pediatr Res 93, 1672–1678 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02217-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02217-2

This article is cited by

-

Parent and staff perceptions of racism in a single-center neonatal intensive care unit

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Equity, inclusion and cultural humility: contemporizing the neonatal intensive care unit family-centered care model

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

Disparity drivers, potential solutions, and the role of a health equity dashboard in the neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study

Journal of Perinatology (2023)