Abstract

Although most recent research on energy balance focusses on energy intake (EI) there is still need to think about both sides of the energy balance. Current research on energy expenditure (EE) relates to metabolic adaptation to negative energy balance, mitochondrial metabolism associated with aging, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the role of EE in hunger and appetite control, non-shivering thermogenesis and brown adipose tissue activity, cellular bioenergetics as a target of obesity treatment and the evolutionary and ecological determinants of EE in humans and other primates. As far as regulation of energy balance is concerned there is recent evidence that EE rather than body weight is under tight control. Biologically, EE is maintained within a narrow physiological range. An EE-set point has been proposed as the width between the upper and lower boundaries of the individual EE range. Regulation of EE may fail in very obese patients with an EI above their upper boundary and after drastic weight loss when patients may go far below their lower EE boundary and thus are loosing control. In population studies, fat-free mass (FFM) and its composition (that is, the proportion of high to low metabolic rate organs) are major determinants of EE. It is tempting to speculate that tight biologic control of EE is related to brain energy need, which is preserved at the cost of peripheral metabolism. There is a moderate heritability of EE, which is independent of the heritability of FFM. In future, metabolic phenotyping should focus on the EE–FFM relationship rather than on EE-values alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thirty years ago, research on regulation of energy balance nearly exclusively focussed on energy expenditure (EE). At that time individual components of daily energy expenditure (=total energy expenditure, TEE) had been characterized in detail. A 70 kg man has a TEE of 2500 kcal/day with 1500 kcal (or 60%) for resting energy expenditure (REE), about 750 kcal (or 30%) for activity-related energy expenditure (AEE, the most variable component of TEE), 250 kcal (or 10%) for diet-induced thermogenesis and another variable component of +/− 250 kcal for metabolic adaptation to negative or positive energy balance.1, 2, 3, 4 This period of intensive research is reflected by some highly ranked and so-called landmark papers addressing the association between EE, weight gain and overweight. Longitudinally, a low REE relative to size was found to be a predictor of weight gain.5, 6, 7, 8 These findings fed a long-lasting discussion about whether obesity is due to either high energy intake (EI) or low EE (for example, refs 9, 10, 11). As (i) most obese subjects have a high rather than a low EE,12 (ii) intra-individual variance of EE is small,1, 3 (iii) no differences in EE were found either between adults living in developing compared with industrialized countries13 or between hunter gatherers and western groups14 although they were different in mean BMI, and (iv) longitudinally, AEE slightly increased rather than decreased in an European population with an increasing prevalence of overweight,15 and was not protective against weight gain,16, 17 the focus of research had shifted from EE to EI as the major determinant of a positive energy balance and obesity.18, 19, 20

Population-wide increases in EI were considered to explain the increases in obesity prevalence observed during the last 40 years. However, this idea remains to be proven in individual patients. In humans, assessment of EI is inaccurate and severely biased in overweight subjects.21, 22, 23 It was only recently that accurate assessment of changes in body composition together with TEE as measured by doubly labeled water and advanced mathematical modeling allowed objective measures of EI.24, 25, 26 When compared with EI, research on EE downsized during the last decades leaving a relatively small number of experts in this area only. However, research on EE is still challenging and currently relates to (i) metabolic adaptation to negative energy balance,27, 28 (ii) mitochondrial metabolism associated with aging, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (iii) the role of REE in hunger and appetite control,37 (iv) non-shivering thermogenesis and brown adipose tissue,38, 39, 40 (v) cellular bioenergetics as a target of obesity treatment41 and (vi) on the evolutionary and ecological determinants of TEE in humans and other primates.42 It is obvious that there is still need to think about both sides of the energy balance.

EI or EE? The case of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition

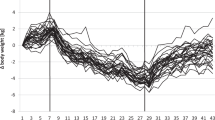

Pharmacological inhibition of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) is now used for metabolic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. It results in glucosuria of about 90 g/day. This intervention also provides some insights into the regulation of energy balance (Figure 1a). Mathematical modeling of energy balance revealed that SGLT2-inhibition resulted in an increase in EI at unchanged EE.43 Again, this finding gives rise to the idea that regulation of energy balance is about EI, which is also in line with genetic studies in which all known causes of human obesity are related to defects in the regulation of EI.19, 20 However, taking a second look at the SGLT2-inhibition data,43 it is obvious that EI increased only by 200–250 kcal/day (Figure 1b). As urinary energy losses were between 300 and 400 kcal/day, an energy gap remained, which resulted in an involuntary weight loss of about 2 kg within the observation period.43

Schematic presentation of the energy balance paradigm. (a) Body weight follows the difference between EI (energyin) and EE (energyout). With increasing body weight energyout increases. By contrast, reducing body weight decreases energyout. Vice versa there are no effects of increases in energyout by strenuous exercise on body weight. An increase in body weight does not automatically result in a compensatory decrease in energyin. Body weight-independent feedback controls between energyout and energyin had been proposed but have only been shown for underfeeding. (b) Pharmacological inhibition of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) results in glucosuria of about 90 g/day. To test the energy balance paradigm the effects of SGLT2-inhibition on energyin and energyout has to be tested. (c) SGLT2-inhibition resulted in an increase in energyin with no changes in energyout. However, an unchanged EE the increase in energyin does not match urinary energy losses resulting in a negative energy balance. See Ferrannani et al. 43 and text for further details.

Thus, during SGLT2-inhibition EI increased but was not perfectly controlled to match urinary energy losses and EE. By contrast, EE was kept constant suggesting that it is tightly controlled (Figure 1c). It is worthwhile to remember that oxygen consumption (similar to body temperature and heart rate) is vitally important and has to be strictly controlled as a matter of survival. The SGLTs-inhibition experience also showed that there is no tight feedback control of EI by EE. This is against the idea of other authors.37 Altogether the data give evidence for the idea that EE rather than EI is under tight control and thus is the major determinant of energy balance.

It remains unclear why EE did not slow down with weight loss observed during GLT2-inhibition.43 Pharmacologically-induced glucosuria was associated with a fall in circulating insulin levels together with a shift of fuel utilization to fats and a considerable increase in the plasma concentration of ketone bodies resembling metabolic adaptation to starvation.44 It has been shown previously that adaptive thermogenesis (AT) is an immediate response to negative energy balance and the fall in insulin secretion, AT occurs even in the absence of significant weight loss.45, 46 However, (i) detailed body composition analysis to adjust EE has not been performed in the group of diabetic patients43 and (ii) AT is in the order of 70 kcal,45 which is within the precision of 3 or more than 5% of either indirect calorimetry and doubly labeled water measurements, respectively.27, 47 Thus, minor changes in EE may have been overlooked in the clinical data on GLT2-inhibition.43 Anyhow, the observed weight loss of diabetic patients points out to the energy gap reflecting that EI and EE did not exactly adapt to each other.

Putting EE into perspective

Energy balance and body weight are under biological control allowing compensatory adjustments in both, EI and EE. This idea is mainly based on animal data. In humans, intra-individual and long-term observations suggest that body weight is relatively constant, which is taken as indirect evidence for a precisely controlled set point of body weight.48 The idea is also in line with clincial observations that after weight loss most obese patients more or less return to their original fatness suggesting a pre-given target weight (or set point;48). As far as energy balance is concerned, some basic assumptions of regulation of body weight come true. For example, an increase/decrease in EI results in an increase/decrease of body weight with a subsequent increase/decrease in EE. By contrast, increasing AEE by strenuous exercise has no or only minor effects on EI and body weight, which has been explained by compensatory decreases in REE,49, 50 reflecting an exercise-induced reduction in stress, endocrine and inflammatory activities. Furthermore, increasing body weight by an increase in EI does not inhibit EI or stimulate AEE as possible compensatory mechanisms. Finally, overfeeding does not result in a weight-independent adaptation of EE, that is, energy dissipation, whereas a mass-independent reduction of EE occurs with underfeeding.51 Obviously, regulation of energy balance does not always result in a stable body weight. In fact EI is not only determined by homeostatic metabolic mechanisms (regulating EI and EE to keep body weight at a set point), but is also influenced by non-homeostatic hedonic mechanisms (related to an obesogenic environment and irrespective of body's energetics). Following that idea two different types of obesity, metabolic vs hedonic obesity have been defined.52

An alternative view on the biology of energy balance is that EE rather than body weight is under tight control. Physiologically, EE is maintained within a target range suggesting that there is an EE-set point, which has been proposed by Pontzer et al.42, 49 Intra-individual variations of EE are below 10% with between subject variation between 10 and 20%.3, 42, 53 Among human populations, EE is similar and independent of lifestyles and cultural or socioeconomic conditions.50 EE increases with low and moderate physical activity but plateaus at long-term high activities to maintain EE within the target range (that is, EE is constraint with respect to physical activity49). EE does not increase with high EI.51 As a first concept, intra-individual changes in body weight follow the missmatch between (imperfectly controlled) EI and (tightly regulated) EE. When EI is outside the target range of EE, a missmatch between EI and EE occurs.

To understand changes in body weight, the EE-set point model has to be extended because there is an additional (and may be to some degree independent of the EE-set point) regulation of allocation or partitioning of energy to (during overfeeding) or from (during underfeeding) fat mass and FFM, respectively. Partitioning of either fat mass and FFM or organ and tissue masses within FM and FFM or FM and FFM between different regions of the body or at the molecular level within cells explains the variance in individual weight changes at a given energy balance.54 Besides energy balance and macronutrient intake partitioning is determined of fat mass, age, gender, physical activity, inactivity, growth and reproduction, it is controlled by endocrine determinants (for example, insulin, IGF-1, testosterone, cortisol and T3) and during chronic inflammation.

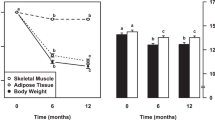

Energy transfer is central in physiology, EE is a physiological trait. FFM is it's major determinant accounting for 50–75% of the variance in EE between subjects living in Western societies.3, 42, 53 Correlation coefficients between body mass (or FFM) and REE or TEE are high (Figure 2; refs 53, 55). Concomitantly, REE per unit weight (or REE on FFM) decreases with increasing weight or FFM documenting that in addition to FFM composition (and thus the specific metabolic activity of FFM, which is explained by the proportion of high to low metabolic rate organs within FFM) adds to the variance of REE (Figure 2; ref. 55). Comparing these associations in different age groups the confounding effect of age becomes evident too (Figure 2).

Associations between FFM and REE in grandparents (a), parents (b) and children (c) of 149 nuclear families of the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study. In addition, the corresponding associations between REE per FFM and FFM (reflecting specific metabolic activities of FFM) are shown (d–f). Data are from Bosy-Westphal et al.69 Detailed characterization of the study population is shown in Table 1. See text for further details.

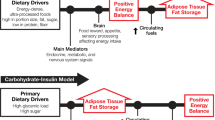

Figure 3 illustrates the view of a putative EE-set point. This extends Pontzer’s hypothesized concept on ontogenetic responses in body size and EE to environmental signals, food availability and physical activity in different populations.42, 49 During normal daily life conditions, shifts in EE with food intake and/or physical activity are mostly body mass-dependent. Changes in the EE–FFM relationship occur within a narrow target range. During short-term, the boundaries of that range are under biological control, whereas environmental and ecological factors may shift that boundaries over longer periods of time. Following a ‘dual intervention point model’,56 the lower and upper limits are EE-set points where biologic control occurs. Between these boundaries EE is passively regulated following cellular ATP demand, which is given by ADP availability plus mitochondrial carbon load. For a given upper EE-set point a mass-independent increase in EE (that is, going beyond the upper boundary) with overfeeding does not occur in humans, whereas minor energy sparing (that is, going below the lower boundary) is seen with caloric restriction. This may be taken as evidence for regulation at the lower EE-set point, whereas there is no defense against weight gain.51 This idea points to a possible asymmetry in the control of EE.51 If this is true, regulation differs at both boundaries and is efficient in response to weight loss only.

Hypothesized responses of body size and EE to physical activity and food availability. This graph has been modified according to the original idea published by Pontzer et al.49, 50 Pontzer proposed that physical activity and food availability are inversely correlated among human populations. Then populations vary along the axis given by the arrow in the center. Body weight and EE are high at high food availability and EI. Vice versa body weight and EE are low at low EI and high physical activity. At strenuous exercise EE is constrained. Contrary to Pontzer, we propose that EE is controlled within a relatively narrow range (characterized by an upper and a lower boundary) reducing the slope of the arrow in the original graph.49 Then, obese subjects may be considered to be outside the EE control range, that is, at chronically high EI EE cannot increase above the upper boundary and match for EI. By contrast, during caloric restriction EI is below the lower boundary of EE. In this situation, EE can be slightly reduced below the lower boundary (that is, AT). However after considerable weight loss with drastic dieting together with heavy exercising (as shown in the ‘biggest looser competition’, see Speakmen et al.56) AT becomes more pronounced and may persist for years carrying the risk of weight regain.28, 51 This situation may reflect a damage of the biologic control of EE at the lower boundary. Our model assumes that tight biological control of EE results in a missmatch between EI and EE and thus changes in body weight.

The width between the two boundaries of EE may vary between individual subjects, which again may relate to inter-individual differences in the propensity of weight gain or weight loss. Regulation of EE may fail in very obese patients (Figure 3). They live in a ‘low activity high food-availability setting’49 and their EE is at or above the upper boundary of the body mass–EE relationship. If this is true the proposed upper EE-set point fails to match EI in obese patients. As far as the lower boundary is concerned, drastic weight loss (due to severe dietary restriction plus excessive exercise) in very obese patients (as seen in the participants of the ‘biggest looser’ competition) may ‘destroy’ the lower set point resulting in persistent ‘very low REE’ as observed in the ‘biggest looser’ competition during re-gaining weight over a 6-year follow-up period (ref. 57; Figure 3).

Energy allocation to the brain controls body EE

Within the body, allocation of available energy follows basal needs of individual organs and tissues with additional needs during growth, pregnancy, lactation or diseases. The brain has a hierarchical position in whole-body energy metabolism. Although brain mass accounts for 2% of body weight only, it’s EE contributes to about one-fifth of REE, that is, in normal weight subjects 20% of the energy is allocated to the brain (ref. 58; Figure 4). Energy allocation differs by weight status and during changes of body weight. When compared with normal weight subjects the proportion brain EE to whole-body EE is 23% in underweight subjects, whereas obese subjects are down to 17% (Figure 4). Energy allocation to peripheral organs (like skeletal muscle) is relatively higher during growth and adolescence.59 As brain is the only organ, which does not lose weight with weight loss,60 its position within whole-body energy allocation is unique. Comparing humans and apes the larger brain size of humans explains their greater EE.58, 61, 62 As correlations between human brain mass and FFM were low and FFM explained 5–6% of the variance in brain mass only,58 EE of the brain and the rest of body mass have to be discussed separately.

Association between FFM and total, brain and body REE in 267 subjects (55.8% females, 44.2% males) at a mean age of 28.9 years (range: 18–39.4 years). Brain REE was calculated from MRI-derived masses times-specific metabolic rate (for details see Müller et al.63). Body REE was then calculated as the difference between total REE (as measured by indirect calorimetry) and brain REE. For further details of the study population see Müller et al.,74 Bosy-Westphal et al.,75 Geisler et al.76

Brain REE can be calculated from MRI-derived brain masses times brain’s specific metabolic rate (see Müller et al.63 for details). Both, brain EE and body EE increase with increasing FFM (Figure 4). However there is a 10-fold difference in the slopes of the EE–FFM relationships reflecting a relatively narrow range in brain mass and metabolism at different body masses (Figure 4). At a mean mass of 1.5 kg, brain REE accounted for 21.2% of whole-body REE, this number decreased with increasing FFM. For comparison, 27.5 kg of skeletal muscle mass contributed to 20.7% of REE with higher values at higher FFM (that is, specific metabolic rates of muscle and brain differ by a factor of 18). However, in a multiple linear regression analysis the proportion of brain to FFM explained 46% of the variance in REE, whereas the proportion of muscle mass to FFM explained 8% only.

These data may add to the idea that the brain demands a constant energy budget and thus keeps whole-body EE within a tight range to preserve its own energy supply. The brain tries to keep neuronal ATP concentrations constant and a constant energy supply from the body occurs by a so-called ‘brain pull mechanism’.64 This is obvious during food shortage where allocation of energy from body periphery towards the brain is brought about by a decrease in insulin secretion at concomitant increases in the pituitary and adrenal stress response reflected by an increased cortisol release and increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system.64 Brain size and brain EE are preserved at the cost of peripheral metabolism.

Is EE a heritable trait?

Inter-individual differences in EE are partly influenced by the genotype. The genetic effect may reach 40% of the variance in EE.65 However there are only few studies, which had addressed this issue limiting the present evidence on the genetics of EE. In monozygotic and dizygotic twins heritability estimates of REE were 42% but most of the effect was explained by the heritability of FFM.65, 66 Heritability estimates were lower based on the calculation of parent–offspring associations.65, 67, 68, 69 When compared with twin studies heritability of REE (adjusted for FFM, age and sex) was about 30% in family studies.

In a three generation study on 149 nuclear families, which was part of the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS70), heritability (as calculated over three generations) was 33% for FFM and 30% for REE adjusted for FFM.69 Re-calculation of the data of this study population (Table 1) revealed a generation effect (Table 2). Heritability of FFM was 73% in the older generation (that is, the grandparent–parent relationship) compared with 43% in the younger generation (that is, the parent–child relationship). By contrast, there was no difference in heritabilities between generations either in REE, REE adjusted for FFM and residuals of REE on FFM. After suitable adjustments for FFM, heritabilities of REE reached 38–45%, which is slightly higher than was previously assumed.65, 67 These data suggests that REE is moderately heritable and there is a genetic effect on REE, which is independent of the genetic effect on FFM. As heritability estimates (i) vary during childhood and adulthood,71 (ii) do not differentiate between genetic effects, the effects of shared environments and a possible gene-by-environment interaction and (iii) are affected by body composition methodology,72 the ‘true’ genetic effect on REE remains to be calculated.

The present heritability estimates do not really address the conceptual model shown in Figure 3. Following the ‘dual intervention point model’ of the EE-set point,56 the genetic effect is not about one EE value but about a range of EEs and its boundaries, which are assumed to be under biological control. To address this issue intra-individual variations of EE in response to various controlled conditions (for example, during over- and underfeeding as measured for example, in the setting of a respiration chamber) are to be characterized in greater groups of twins or nuclear families.73

Conclusions

EE is a classical issue of nutrition research. Most of our knowledge about EE dates back to research done 20 and more years ago. As assessment of EE did not add much to explain weight gain and overweight most scientists had moved to the issue of EI. After a nearly 20 year period of intensive research on EI, EE is now coming back into the focus of research on body weight regulation. The present evidence suggests that EE is a vital sign, thus, it is under tight biological control. There is evidence for an EE-set point. By contrast, EI is not perfectly controlled. This is also reflected by the population-wide prevalence of weight gains and overweight. To get further insights suitable protocols for assessment of EE (that is, assessing EE in subjects during varying and controlled conditions) are warranted taking into account suitable concepts and methods for assessment of body composition.73 In future, changes in the EE–FFM relationship rather than EE-values alone will give rise to appropriate phenotyping.

Change history

08 March 2017

Updated online 8 March 2017: This article was originally published under a standard EJCN license, but has now been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. The PDF and HTML versions of the paper have been modified accordingly.

References

Woo R, Daniels-Kush R, Horton ES . Regulation of energy balance. Ann Rev Nutr 1985; 5: 411–433.

Jéquier E . Energy utilization in human obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1987; 499: 73–83.

Ravussin E, Bogardus C . Relationship of genetics, age, and physical fitness to daily energy expenditure and fuel utilization. Am J Clin Nutr 1989; 49, 968–975.

Saltzman E, Roberts SB . The role of energy expenditure in energy regulation: Findings from a decade of research. Nutr Rev 1995; 53: 209–220.

Griffiths M, Payne PR . Energy expenditure in small children of obese and non-obese parents. Nature 1976; 260: 698–700.

Ravussin E, Lillioja S, Knowler WC, Christin L, Freymond D, Abbott WG et al. Reduced rate of energy expenditure as a risk factor for body-weight gain. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 467–472.

Roberts SB, Savage J, Coward WA, Chew B, Lucas A . Energy expenditure and energy intake in infants born to lean and overweight mothers. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 461–466.

Grifiths M, Payne PR, Stunkard AJ, Rivers JPW, Cox M . Metabolic rate and physical development in children at risk of obesity. Lancet 1990; 336: 76–78.

Roberts SB, Leibel RL . Excess energy intake and low energy expenditure as predictors of obesity. Int J Obes 1998; 22: 385–386.

Cambpell LV . A change of paradigm: obesity is not due to either ‘excess’ energy intake or ‘inadequate’ energy expenditure. Int J Obes 1998; 22: 1137.

Wells JCK . Is obesity due to high energy intake or low energy expenditure? Int J Obes 1998; 22: 1139–1140.

Carneiro IP, Elliott SA, Siervo M, Padwal R, Bertoli S, Battezzati A et al. Is obesity associated with altered energy expenditure? Adv Nutr 2016; 7: 476–487.

Dugas LR, Harders R, Merrill S, Ebersole K, Shoam DA, Rush EJ et al. Energy expenditure in adults living in developing compared with industrialized countries: a meta-analysis of doubly labeled water studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93: 427–441.

Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Wood BM, Mabulla AZP, Racette SB, Marlowe FW . Hunter-gatherer energetics and human obesity. PLoS One 2012; 7: e40503.

Westerterp KR, Speakman JR . Physical activity and energy expenditure has not declined since the 1980 s and matches energy expenditures of wild mammals. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1256–1263.

Tataranni PA, Harper IT, Snitker S, Del Parigi A, Vozarova B, Bunt J et al. Body weight gain in free-living Pima Indians: effect of energy intake vs energy expenditure. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 1578–1583.

Plasqui G, Westertero KR . Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: an evaluation against doubly labeled water. Obesity 2007; 15: 2371–2379.

Jéquier E, Tappy L . Regulation of body weight in humans. Physiol Rev 1999; 79: 451–480.

Friedman JM . Leptin at 14 y of age: an ongoing story. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 973S–979S.

Schwartz GJ, Zeltser LM . Functional organization of neuronal and humoral signals regulating feeding behavior. Ann Rev Nutr 2013; 33: 1–21.

Schoeller DA, Thomas D, Archer E, Heymsfield SB, Blair SN, Goran MI et al. Self-report-based estimates of energy intake offer an inadequate basis for scientific conclusions. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 97: 1413–1415.

Dhurandhar NV, Schoeller D, Brown AW, Heymsfield SB, Thomas D, Sørensen TI et al. Energy balance measurement: when something is not better than nothing. Int J Obes 2015; 39: 1109–1113.

Dhurandhar NV, Brown AW, Thomas D, Allison DB, Energy Balance Measurement Working Group. We agree that self-reported energy intake should not be used as a basis for conclusions about energy intake in scientific research. J Nutr 2016; 146: 1141–1142.

Sanghvi A, Redman LM, Martin CK, Ravussin E, Hall KD . Validation of an inexpensive and accurate mathematical method to measure long- term changes in free-living energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102: 353–358.

Thomas DM, Schoeller DA, Redman LA, Martin CK, Levine JA, Heymsfield SB . A computational model to determine energy intake during weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 1326–1331.

Hall KD . Estimating human energy intake using mathematical models. Am J Clin Nutr 2014; 100: 744–745.

Dulloo AG, Jaquet J, Montani JP, Schutz Y . Adaptive thermogenesis in human body weight regulation:more a concept than a measurable entity. Obes Rev 2012; 13: 105–121.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A . Adaptive thermogenesis with weight loss in humans. Obesity 2013; 21: 218–228.

Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 2003; 300: 1140–1142.

Lowell BB, Shulman GI . Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science 2005; 307: 384–387.

Kelley DE . Skeletal muscle fat oxidation: timing and flexibility are everything. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 1699–1702.

Muoio DM . Metabolic inflexibility: When mitochondria indecision leads to metabolic gridlock. Cell 2014; 159: 1253–1262.

Ritov VB, Menshikova EV, Azuma K, Wood R, Toledo FG, Goodpaster BH et al. Deficiency of electron transport chain in human skeletal muscle mitochondria in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010; 298: E49–E58.

Petersen KF, Morino K, Alves TC, Kibbey RG, Dufour S, Sono S et al. Effect of aging on muscle mitochondrial substrate utilization in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015; 112: 11330–11334. (Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015; 112: E5762).

Koliaki C, Roden M . Alterations of mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity in human obesity and diabetes mellitus. Annu Rev Nutr 2016; 36: 337–367.

Apostolopoulou M, Strassburger K, Herder C, Knebel B, Kotzka J, Szendroedi J et al. Metabolic flexibility and oxidative capacity independently associate with insulin sensitivity in individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 2203–2207.

Blundell JE, Caudwell P, Gibbons C, Hopkins M, Naslund E, King N et al. Role of resting metabolic rate and energy expenditure in hunger and appetite control: a new formulation. Dis Models Mech 2012; 5: 608–613.

van Marken Lichtenbelt, WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, Drossaerts JM, Kemerink GJ et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1500–1508.

Betz MJ, Enerbäck S . Human brown adipose tissue: what we have learned so far. Diabetes 2015; 64: 2352–2360.

Celi FS, Le TN, Ni B . Physiology and relevance of human adaptive thermogenesis response. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015; 26: 238–247.

Tseng Y-H, Cypress AM, Kahn CR . Cellular bioenergetics as a target for obesity treatment. Nat Rev 2010; 9: 465–481.

Pontzer H . Energy expenditure in humans and other primates: a new synthesis. Ann Rev Anthropol 2015; 44: 169–187.

Ferrannini G, Hach T, Crowe S, Sanghvi A, Hall KD, Ferrannini E . Energy balance after sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1730–1735.

Ferrannini E, Baldi S, Frascerra S, Astiarraga B, Heise T, Bizzotto R et al. Shift to fatty substrate utilization in response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in subjects without diabetes and patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2016; 65: 1190–1195.

Müller MJ, Enderle J, Pourhassan M, Braun W, Eggeling B, Lagerpusch M et al. Metabolic adaptation to caloric restriction and subsequent refeeding: the Minnesota starvation experiment revisited. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102: 807–819.

Müller MJ . Adaptive thermogenesis: do we need new thinking? Obesity 2016; 24: 160–1611.

Bader N, Bosy-Westphal A, Dilba B, Müller MJ . Intra- and interindividual variability of resting energy expenditure in healthy male subjects—biological and methodological variability of resting energy expenditure. Br J Nutr 2005; 94: 843–849.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Heymsfield SB . Is there evidence for a set point that regulates human body weight? F1000 Med Rep 2010; 2: 59.

Pontzer H . Constrained total energy expenditure and the evolutionary biology of energy balance. Exerc Sports Sci Rev 2015; 43: 110–116.

Pontzer H, Durazo-Arvizu R, Dugas LR, Plange-Rhule J, Bovet P, Forrester TE et al. Constrained total energy expenditure and metabolic adaptation to physical activity in adult humans. Curr Biol 2016; 26: 410–417.

Müller MJ, Enderle J, Bosy-Westphal A . Changes in energy expenditure with weight gain and weight loss in humans. Curr Obes Rep 2016; 5: 413–423.

Yu Y-H, Vasseli JR, Zhang Y, Mechanick JI, Korner J, Peterli R . Metabolic vs. hedonic obesity: a conceptual distinction and its clinical implication. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 234–247.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Klaus S, Kreymann G, Lührmann PM, Neuhäuser-Berthold M et al. World Health Organization equations have shortcomings for predicting resting energy expenditure in persons from a modern, affluent population: generation of a new reference standard from a retrospective analysis of a German database of resting energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80: 1379–1390.

Bosy-Westphal A, Kahlhöfer J, Lagerpusch M, Skurk T, Müller MJ . Deep body composition phenotyping during weight cycling: relevance to metabolic efficiency and metabolic risk. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 36–44.

Heymsfield SB, Thomas D, Bosy-Westphal A, Shen W, Peterson CM, Müller MJ . Evolving concepts on adjusting human resting energy expenditure measurements for body size. Obes Rev 2012; 13: 1001–1014.

Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, Bray MS, de Castro JM, Clegg DJ et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4: 733–745.

Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, Kerns JC, Knuth ND, Brychta R et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after ‘The Biggest Loser’ competition. Obesity 2016; 24: 1612–1619.

Heymsfield SB, Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Thomas D, Shen W . Human brain mass: similar composition associations as observed across mammals. Am J Hum Biol 2012; 24: 479–485.

Kubera B, Bosy-Westphal A, Peters A, Braun W, Langemann D, Neugebohren S et al. Energy allocation between brain and during ontogenic development. Am J Hum Biol 2013; 25: 725–732.

Peters A, Bosy-Westphal A, Kubera B, Langemann D, Goele K, Later W et al. Why doesn’t the brain lose weight, when obese people diet? Obes Facts 2011; 4: 151–157.

Peters A, Hitze B, Langemann D, Bosy-Westphal A, Müller MJ . Brain size, body size and longevity. Int J Obes 2010; 34: 1349–1352.

Pontzer H, Brown MH, Raichlin DA, Dunsworth H, Hare B, Walker K et al. Metabolic acceleration and the evolution of human brain size and life history. Nature 2016; 533: 390–393.

Müller MJ, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB, Schautz B, Bosy-Westphal A . Advances in the understanding of specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues in humans. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2013; 16: 501–508.

Kubera B, Hubold C, Zug S, Wischnath H, Wilhelm I, Hallschmid M et al. The brain’s supply and demand in obesity. Front Neuroenergetics 2012; 4: 4.

Bouchard C, Perusse L, Deriaz O, Després JP, Tremblay A . Genetic influences on energy expenditure in humans. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1993; 33: 345–350.

Hewitt JK, Stunkard AJ, Caroll D, Sims J, Turner JR . A twin study approach towards understanding genetic contributions to body size and metabolic rate. Acta Genet Med Gemellol 1991; 40: 133–137.

Bogardus C, Lillioja C, Ravussin S, Abbott E, Zawadzki W, Young JK et al. Familial dependence of the resting metabolic rate. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 96–106.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Geisler C, Onur S . Physiological and pathological changes in the nutritional status over life time. In: Lochs H, Thomas DR (eds). Home Care Enteral Feeding, vol. 10. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series Clinical and Performance Program, 2004, : pp 31–44.

Bosy-Westphal A, Wolf A, Bührens F, Hitze B, Czech N, Mönig H et al. Familial influences and obesity-associated metabolic risk factors contribute to the variation in resting energy expnediture: the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 1695–1701.

Bosy-Westphal A, Onur S, Geisler C, Wolf A, Korth O, Pfeuffer M et al. Common familial influences on clustering of metabolic syndrome traits with central obesity and insulin resistance: the Kiel obesity prevention study. Int J Obes 2007; 31: 784–790.

Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R, Hur YM, Yokoyama Y, Honda C et al. Genetic and environmental effects on body mass index from infancy to the onset of adulthood: an individual-based pooled analysis of 45 twin cohorts participating in the Collaborative project of Development of Anthropometrical measures in Twins (CODATwins) study. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 104: 371–379.

Elder SJ, Roberts SB, McCrory MA, Das SK, Fuss PJ, Pittas AG et al. Effect of body composition methodology on heritability estimation of body fatness. Open Nutr J 2012; 6: 48–58.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Krawczak M . Genetic studies of common types of obesity: a critique of the current use of phenotypes. Obes Rev 2010; 11: 612–618.

Müller MJ, Langemann D, Gehrke I, Later W, Heller M, Glüer CC et al. Effect of constitution on mass of individual organs and their association with metabolic rate in humans—a detailed view on allometric scaling. PLoS One 2011; 6: e22732.

Bosy-Westphal A, Braun W, Schautz B, Müller MJ . Issues characterizing resting energy expenditure in obesity and after weight loss. Front Physiol 2013; 4: 47.

Geisler C, Braun W, Pourhassan M, Schweitzer L, Glüer CC, Bosy-Westphal A et al. Age-dependent changes in resting energy expenditure (REE): insights from detailed body composition analysis in normal and overweight healthy Caucasians. Nutrients 2016; 8: 322.

Blangero J, Almasey L, Dyer T et al Sequential oligogenic linkage analysis routines. SOLAR, version 1.4.1 edn, 1999.

Acknowledgements

Our own research was supported by grants of the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 01EA1336; BMBF Kompetenznetz Adipositas Core Domain Body Composition, Körperzusammensetzung 01G1125), the German Research Foundation (DFG Mü 714/8-3 and DFG Bo 3296 1-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, M., Geisler, C. From the past to future: from energy expenditure to energy intake to energy expenditure. Eur J Clin Nutr 71, 358–364 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.231

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.231

This article is cited by

-

Discovery and preclinical efficacy of HSG4112, a synthetic structural analog of glabridin, for the treatment of obesity

International Journal of Obesity (2021)

-

SES-of-Origin and BMI in Youth: Comparing Germany and Minnesota

Behavior Genetics (2019)

-

Oncostatin M in the development of metabolic syndrome and its potential as a novel therapeutic target

Anatomical Science International (2018)

-

Prevalence of overweight and obesity among police officers in Riyadh City and risk factors for cardiovascular disease

Lipids in Health and Disease (2017)

-

Melatonin as a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant: one of evolution’s best ideas

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2017)