Abstract

Chlamydia pneumoniae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia psittaci were detected at low frequencies (<20%) among 69 pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, 30 other lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) and 44 non-LPD. The incidence of individual Chlamydiae was generally higher in MALT lymphoma than non-LPD, although not reaching statistical significance. Mycoplasma pneumoniae DNA was not detected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma arises from the MALT acquired as a result of chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorder (Isaacson and Du, 2004). The inflammatory process and the accompanying immunological responses provide a microenvironment essential for malignant transformation and for the subsequent expansion of the transformed clone. This is best exemplified in gastric MALT lymphoma, which is caused by chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and can be effectively treated by eradication of the organism with antibiotics (Wotherspoon et al, 1993). Growing evidence indicates that the development of non-gastric MALT lymphoma is also associated with infection by microbial pathogens. Borrelia burgdorferi and Campylobacter jejuni are associated with cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and immunoproliferative small intestinal disease, respectively (Cerroni et al, 1997; Lecuit et al, 2004). Recent studies show that Chlamydia psittaci is variably associated with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in different geographical regions (Ferreri et al, 2004; Chanudet et al, 2006) and eradication of the organism results in complete regression of the lymphoma in some cases (Ferreri et al, 2005).

The aetiological factors underlying the development of pulmonary MALT lymphoma are unknown. Nonetheless, Chlamydia sp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae can cause chronic pulmonary diseases such as chronic bronchitis and adult-onset asthma (Bjornsson et al, 1996; Daian et al, 2000), and chronic infection with C. pneumoniae or M. pneumoniae has been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer (Pehlivan et al, 2004; Littman et al, 2005). C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis infections, particularly the former, are also associated with an increased risk of lymphoma although their specific association with pulmonary MALT lymphoma is unclear (Anttila et al, 1998). The present study was thus designed to examine the potential association of Chlamydiae and Mycoplasma infection with pulmonary MALT lymphoma.

Materials and methods

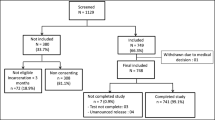

Archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lung biopsies (mainly parenchymal biopsies, occasionally biopsies of the bronchial mucosa) of 159 patients from 3 geographical areas, obtained between 1983 and 2006, were analysed. In all cases, the lung was the primary site of the disease. Local ethical guidelines were followed for the use of archival paraffin-embedded tissues for research and such use was approved by the local ethics committees of the author's institutions.

DNA was purified from whole tissue sections, and checked for integrity by multiplex PCR amplification of variously sized human gene fragments (100, 200, 300 and 400 bp) (Chanudet et al, 2006). Of the 159 cases, 143 had adequate materials as judged by quality control PCR and were thus suitable for PCR-based screening of microbial pathogens. These included 69 primary pulmonary MALT lymphomas, 30 pulmonary cases with other lymphoproliferative disorders (other-LPD), and 44 lung biopsies without any histological evidence of an LPD (non-LPD) (Table 1).

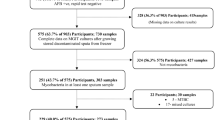

The detection of C. psittaci, C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis was carried out separately using a previously described Touchdown PCR (Chanudet et al, 2006). Mycoplasma pneumoniae was detected by PCR of the Mycoplasma-associated P1 adhesion protein gene as described previously (Hardegger et al, 2000). Stringent laboratory procedures for PCR set-up and product analysis were carefully followed to avoid any potential cross-contamination. PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gels. Positive PCR products were purified and sequenced using an ABI 377 DNA sequencer (ABI PRISM Perkin Elmer) to confirm the specificity of PCR. In each case, three independent PCRs were carried out for each microbial species and only cases with positive PCR results in at least two of the three independent reactions were regarded as positive (Ferreri et al, 2004; Chanudet et al, 2006).

Differences in the prevalence of infectious agents among various lymphoma subtypes and controls were analysed using Fisher's exact test (‘stats Package’ in R version 2.1.1).

t(11;18)(q21;q21) and t(1;14)(p22;q32) were screened in 33 cases of MALT lymphoma by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation in previous investigations (Ye et al, 2003).

Results

Of the 143 cases screened for the presence of Chlamydia and Mycoplasma (Figure 1), quality control PCR did not show any differences in the quality of DNA samples from MALT lymphoma or control groups, or from different geographical regions. Sequencing of PCR products confirmed specific amplification of all PCR primer sets.

PCR detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia psittaci DNA in pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma specimen (10% polyacrylamide gel). M=molecular weight marker; +=positive control; −=negative control; S1–S5=different MALT lymphomas; S2=positive for both C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis.

Overall, 24 of 69 (35%) MALT lymphomas were positive for at least one of the three Chlamydia species, a frequency significantly higher than that in non-LPD (18%, P=0.043) but not other-LPD (27%, P=0.29). With the exception of two cases of MALT lymphoma (one from Italy and the other from UK), the presence of three Chlamydia species was mutually exclusive.

When the prevalence of individual Chlamydia species in various groups was examined within the same geographical region, no significant difference in the prevalence of each Chlamydia species was found between MALT lymphoma and other- or non-LPD group in all the three regions examined (Table 2). Nonetheless, the prevalence of C. trachomatis in MALT lymphoma (19%) was higher than those in other-LPD (5%) and non-LPD (4%) in Germany. Chlamydia pneumoniae was also detected more frequently in MALT lymphoma (23%) than other-LPD group (10%) in Italy. Chlamydia psittaci was found at low frequencies in MALT lymphoma, but absent in control groups in all three geographical regions. There was no correlation between Chlamydia positivity and age or sex of the patients. There was also no correlation between Chlamydia positivity and presence of t(11;18)(q21;q21) and t(1;14)(p22;q32) in 33 cases of MALT lymphoma from the United Kingdom and Germany, in which the translocation status was available from previous investigations. Remarkably, the four cases of DLBCL positive for a Chlamydia infection (three with C. pneumoniae and one with C. trachomatis) were all de novo. Mycoplasma pneumoniae was not detected in any MALT lymphoma and control cases despite the high sensitivity of the PCR, which was capable of detecting as few as three copies of M. pneumoniae genome.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the presence of infectious agents in pulmonary MALT lymphoma. Our results show low frequencies of C. pneumoniae, C. trachomatis and C. psittaci infection in pulmonary MALT lymphomas. The prevalence of the individual Chlamydiae was in general higher in pulmonary MALT lymphoma than non-LPD group. Nonetheless, this is not statistically significant; larger series of both MALT lymphomas and appropriate controls are required to assess the possible association of Chlamydia infection with pulmonary MALT lymphoma.

The low frequencies of Chlamydiae infection observed in pulmonary MALT lymphoma are analogous to the low prevalence of B. burgdorferi in cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and C. psittaci in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma (Cerroni et al, 1997; Chanudet et al, 2006). Together, these observations highlight an important issue for the study of microbial pathogens associated with non-gastric MALT lymphomas. The microbial pathogens associated with MALT lymphoma may reflect the spectrum of infectious agents that are capable of colonising and causing chronic infections at the respective mucosal sites. Unlike stomach where only H. pylori and its related species can survive the hostile acidic environment, lung is susceptible to a wide range of infectious agents. While gastric MALT lymphomas are invariably associated with Helicobacter species, pulmonary MALT lymphoma, similarly to other non-gastric MALT lymphomas, might be associated with several infectious agents. A recent study from Italy showed that 6 of the 13 C. psittaci negative ocular MALT lymphomas also responded to antibiotic treatment, suggesting the presence of other bacteria (Ferreri et al, 2006).

Remarkably, all cases tested in this study were negative for M. pneumoniae despite the high sensitivity of the PCR detection. This, together with the absence of Chlamydia infection in the majority of pulmonary MALT lymphomas, suggests the presence of other aetiological factors in the development of this lymphoma.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Anttila TI, Lehtinen T, Leinonen M, Bloiqu A, Koskela P, Lehtinen M, Saikku P (1998) Serological evidence of an association between chlamydial infections and malignant lymphomas. Br J Haematol 103: 150–156, doi:10.1046/j.1365–2141.1998.00942.x

Bjornsson E, Hjelm E, Janson C, Fridell E, Boman G (1996) Serology of Chlamydia in relation to asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Scand J Infect Dis 28: 63–69

Cerroni L, Zochling N, Putz B, Kerl H (1997) Infection by Borrelia burgdorferi and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol 24: 457–461, doi:10.1111/j.1600–0560.1997.tb01318.x

Chanudet E, Zhou Y, Bacon CM, Wotherspoon AC, Müller-Hermelink HK, Adam P, Dong HY, de Jong D, Li Y, Wei R, Gong X, Wu Q, Ranaldi R, Goteri G, Pileri SA, Ye H, Hamoudi RA, Liu H, Radford J, Du MQ (2006) Chlamydia psittaci is variably associated with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in different geographical regions. J Pathol 209: 344–351, doi:10.1002/path.1984

Daian CM, Wolff AH, Bielory L (2000) The role of atypical organisms in asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 21: 107–111, doi:10.2500/108854100778250860

Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Ponzoni M, De Conciliis C, Dell'Oro S, Fleischhauer K, Caggiari L, Lettini AA, Dal Cin E, Ieri R, Freschi M, Villa E, Boiocchi M, Dolcetti R (2004) Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 586–594, doi:10.1093/jnci/djh102

Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, De Conciliis C, Resti AG, Mazzi B, Lettini AA, Demeter J, Dell'Oro S, Doglioni C, Villa E, Boiocchi M, Dolcetti R (2005) Regression of ocular adnexal lymphoma after Chlamydia psittaci-eradicating antibiotic therapy. J Clin Oncol 23: 5067–5073, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.083

Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, Resti AG, Politi LS, Cortelazzo S, Demeter J, Zallio F, Palmas A, Muti G, Dognini GP, Pasini E, Lettini AA, Sacchetti F, De Conciliis C, Doglioni C, Dolcetti R (2006) Bacteria-eradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a multicentre prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 1375–1382, doi:10.1093/jnci/djj373

Hardegger D, Nadal D, Bossart W, Altwegg M, Dutly F (2000) Rapid detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in clinical samples by real-time PCR. J Microbiol Methods 41: 45–51, doi:10.1016/S0167–7012(00)00135-4

Isaacson PG, Du MQ (2004) MALT lymphoma: from morphology to molecules. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 644–653, doi:10.1038/nrc1409

Lecuit M, Abachin E, Martin A, Poyart C, Pochart P, Suarez F, Bengoufa D, Feuillard J, Lavergne A, Gordon JI, Berche P, Guillevin L, Lortholary O (2004) Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease associated with Campylobacter jejuni. N Engl J Med 350: 239–248

Littman AJ, Jackson LA, Vaughan TL (2005) Chlamydia pneumoniae and lung cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 773–778

Pehlivan M, Itirli G, Onay H, Bulut H, Koyuncuoglu M, Pehlivan S (2004) Does Mycoplasma sp. play role in small cell lung cancer? Lung Cancer 45: 129–130, doi:10.1016/j.luncan.2004.01.007

Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M (1993) Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 342: 575–577, doi:10.1016/0140–6736(93)91409-F

Ye H, Liu H, Attygalle A, Wotherspoon AC, Nicholson AG, Charlotte F, Leblond V, Speight P, Goodlag J, Lavergne-Slove A, Martin-Subero JI, Siebert R, Dogan A, Isaacson PG, Du MQ (2003) Variable frequencies of t(11;18)(q21;q21) in MALT lymphomas of different sites: significatnt association with CagA stains of H pylori in gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood 102: 1012–1018, doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3502

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Riccardo Dolcetti, IRCCS National Cancer Institute, Aviano, Italy, for providing Chlamydiae positive control samples, as well as Dr Chris Bacon and Dr Hongxiang Liu for helpful discussion. The Du Lab is supported by research grants from the Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society, USA and Leukaemia Research Fund, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chanudet, E., Adam, P., Nicholson, A. et al. Chlamydiae and Mycoplasma infections in pulmonary MALT lymphoma. Br J Cancer 97, 949–951 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603981

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603981

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

How we treat mature B-cell neoplasms (indolent B-cell lymphomas)

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2021)

-

Microbiota in cancer development and treatment

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2019)

-

Radical surgery may be not an optimal treatment approach for pulmonary MALT lymphoma

Tumor Biology (2015)

-

Bacteria and tumours: causative agents or opportunistic inhabitants?

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2013)