Abstract

The semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) is a clinical syndrome characterized by neurodegeneration and progressive loss of semantic knowledge. Unlike many other forms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), svPPA has a highly consistent underlying pathology composed of TDP-43 (a regulator of RNA and DNA transcription metabolism). Previous genetic studies of svPPA are limited by small sample sizes and a paucity of common risk variants. Despite this, svPPA’s relatively homogenous clinicopathologic phenotype makes it an ideal investigative model to examine genetic processes that may drive neurodegenerative disease. In this study, we used GWAS metadata, tissue samples from pathologically confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and in silico techniques to identify and characterize protein interaction networks associated with svPPA risk. We identified 64 svPPA risk genes that interact at the protein level. The protein pathways represented in this svPPA gene network are critical regulators of RNA metabolism and cell death, such as SMAD proteins and NOTCH1. Many of the genes in this network are involved in TDP-43 metabolism. Contrary to the conventional notion that svPPA is a clinical syndrome with few genetic risk factors, our analyses show that svPPA risk is complex and polygenic in nature. Risk for svPPA is likely driven by multiple common variants in genes interacting with TDP-43, along with cell death,x` working in combination to promote neurodegeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frontotemporal lobar dementia (FTLD) is a heterogeneous family of progressive neurodegenerative disorders characterized by degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes with corresponding clinical deficits in social processes, language, and executive functioning1. One of the most common FTLD syndromes, semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia (svPPA; also referred to as semantic dementia (SD)) preferentially affects language and semantic processing2,3. svPPA is unique amongst the FTLD spectrum disorders because the vast majority of cases have TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) positive inclusions, with a very small fraction showing other protein pathologies2,4. TDP-43 is a protein heavily involved in RNA metabolic processes including transcription, splicing, and transport5. Despite its relatively consistent clinical presentation and predictable pathological features, little is known about the genetic factors underlying risk for svPPA6.

svPPA poses a unique problem and opportunity amongst the FTLD spectrum disorders2. When contrasted to pathologically diverse syndromes within the FTLD spectrum such as behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), the relative clinical and pathological homogeneity of svPPA (typically TDP-43 Type C) could suggest a shared genetic risk profile across patients. However, very few, if any, common variants have been shown to contribute to the sporadic form of svPPA6,7. This observation is striking when compared to other forms of FTLD in which up to 40% of patients have a positive family history and there are many known, common genetic risk variants1,7,8. This conundrum suggests, among other possibilities, that svPPA risk is more strongly influenced by environmental or developmental factors such as handedness9 and/or that svPPA is by nature highly polygenic. Identifying the genetic contributions to disease is critical as it provides insight into the causal biology underlying deterministic neurodegenerative pathways.

Recent advances have enabled the analysis of multiple sub-GWAS significant loci by integrating heterogeneous risk alleles with experimentally validated outside reference data10. This not only increases statistical power, but also overcomes challenges such as locus heterogeneity to determine novel loci underlying disease risk. We have previously utilized these methods to successfully identify new risk genes and inform the pathobiology of complex diseases like multiple sclerosis11. This approach is particularly powerful because it relies upon previously validated experimental data to link disease-associated genes with one another, further corroborating the biological relevance of risk loci. In this study, we focused our analyses on svPPA not only because it is pathologically homogeneous, but also because previous efforts to identify genetic risk factors associated with svPPA have been limited by small sample sizes amongst single risk loci. Utilizing polygenic strategies to identify risk factors for svPPA presents a unique opportunity, as knowledge gleaned from these analyses could also inform other forms of FTLD resulting from TDP-43 pathology.

Results

This study utilized summary statistics of the phase-1 GWAS data from the International FTD-Genomics Consortium (IFGC), comprised of 2,154 clinically diagnosed FTD spectrum cases and 4,308 controls and a total of 6,026,384 SNPs. Of the 2,154 cases diagnosed with FTD, 361 were diagnosed with the svPPA subtype (referred to as “semantic dementia” in the original study). Cases within the cohort were diagnosed according to the Neary criteria for FTLD12. For additional cohort details, please see Ferrari et al.6.

We generated gene-based p-values for 17,466 genes with data available in the svPPA cohort using the tool versatile gene-based association study (VEGAS). We next generated protein interaction networks (PINs) for the significant genes (VEGAS p < 0.05) using the protein interaction network-based pathway analysis (PINBPA) package. The background PIN database used in our analyses contained 8,960 proteins and 27,724 interactions. The largest network generated (in terms of both nodes and edges) contained 64 nodes (genes) and had 81 edges (protein interactions) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). We evaluated only the largest and most significant network to avoid false positive findings. Notably, TARDBP (the gene encoding TDP-43) was absent from our network, but many genes implicated in cell death (e.g. SMAD3, SMAD4), nuclear trafficking (e.g. RANGAP1), and stress responses (e.g. HNF4A) were present. The svPPA network was within the top 10th percentile for both nodes and edges based on permutation testing.

svPPA Network. Network results are shown for protein interaction network based pathway analysis (PINBPA) in the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia compared to controls. The network genes are color coded according to their respective p-value (see Methods), with warmer colors indicating p-values closer to the minimum value of 1.89E-4 and cooler colors indicating p-values closer to the maximum p-value of 0.05. The size of a node corresponds to closeness centrality (a metric that describes a node’s nearness to other network nodes). The thickness of edges in the network corresponds to edge betweenness (a metric that describes the number of paths going through an edge in the network).

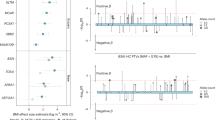

We next explored the gene expression patterns of the svPPA network genes in pathologically confirmed cohorts of FTLD cases versus controls. Fifty-eight of 64 svPPA genes in the dataset (GSE13162) had expression data available. Fifteen of the svPPA network genes (HNF4A, NR5A1, TAL1, SLC2A4, PSEN1, KRT81, MYBL2, UBE2I, EBI3, BATF, ARFRP1, NR6A1, PACS1, PELP1, and TEF) were significantly differentially expressed at an FDR-corrected p < 0.05 in cases when compared to controls (Table 1, Supplementary Table S2). For each gene in the svPPA network we provide a detailed summary of our results with respect to VEGAS results, the top 3 regions expressing each gene in healthy human brain tissue (from the Braineac cohort, http://braineac.org), OMIM biological process implicated for each gene, and known neurodegenerative disease associations in Supplementary Table S3.

To better understand the biological and functional implications of the svPPA gene network, we performed two separate ontological analyses. The first analysis utilized two common and publicly available databases of gene ontologies (Reactome and Gene Ontology [GO] portals)13,14. For the second analysis, we used a recently developed and independent analytical pipeline called weighted protein-protein interaction network analysis (W-PPI-NA) pipeline, which was recently developed by our group15,16.

Sixty-four genes were included in the first svPPA ontological pathway analysis (Supplementary Table S1); genetic enrichment was seen in pathways involved in RNA metabolism, development, immunity, and cell signaling (Table 2 and Supplementary Data S1). Reactome pathways highlighted in our enrichment analysis included broad classifications at the nucleotide level such as nucleotide excision repair, as well as more specific processes including SMAD signaling proteins (fold enrichment = 56.11, p = 1.65 × 10−3), NOTCH (fold enrichment = 66.75, p = 9.56 × 10−7), and Activin (fold enrichment = 74.46, p = 1.79 × 10−2) (summarized in Table 2, full results in Supplementary Table S4).

Our second svPPA ontological pathway analysis – through the W-PPI-NA pipeline – enabled the independent topological characterization of our 64 svPPA network genes. Provided that one svPPA network risk gene – TH1L – did not survive after applying the W-PPI-NA method, the (second) network was ultimately generated using 63 proteins as seeds. We merged the annotations reported in multiple protein-protein interaction (PPI) databases within the IMEX consortium17. After filtering and scoring the protein network, the interactome was composed of 1,495 nodes and 2,407 edges where all but 4 nodes (FSTL3, MRPL30, NR6A1 and EBI3) were interconnected (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S1). Since one protein in the network, UBC, tags protein targets for degradation, it might non-specifically bind any protein in the sub-cellular environment and not necessarily represent a specific functional pathway. We thus excluded UBC from the network’s statistics. We identified the inter-interactome hubs (IIHs) (n = 7) as the core of the network with the highest interconnectivity (Fig. 2D); these nodes were able to bridge over 15% of the entire interactomes (Fig. 2B,C). By comparing the core of the network with randomly sampled parts of the network, we verified that the IIHs-driven network was indeed the most densely connected (Supplementary Fig. S2). The core of the network was made of 37 nodes (7 IIHs and their interactors) and 93 edges. These were strongly interconnected (average number of neighbors = 4.7). We next functionally annotated the interactomes, focusing on GO-BPs (biological processes) using g:Profiler. The first functional enrichment aforementioned in this paragraph was followed by a second iteration of the same procedure but only applied on the densely connected core of the network (Fig. 2D). Our results (Supplementary Data S1) indicated a list of semantic classes that were a subset of the former. Interestingly the subset terms (percentage of retention >12%, i.e. an arbitrary yet robust threshold that takes into account the functions containing the largest number of replicated BP terms in our experimental setting (Fig. 3)) pointed to the following functional blocks: i) ‘RNA metabolism’ and ii) ‘stress’ (Fig. 3) as the common functions characterizing that part of the protein network with strongest cohesion among the initial seeds. Of note, key players within these functional blocks were members of the SMAD protein family. We were thus able to replicate the results obtained through the Reactome analyses using a completely independent and different approach, further supporting the biological roles of svPPA network risk genes.

svPPA Interactome Analyses. (A) Results from the weighted protein-protein interaction network analysis (W-PPI-NA) pipeline are shown for the 64 genes identified using protein interaction network based pathway analysis (PINBPA). Seeds in the results are shown in pink while interactors are shown in blue. (B) The inter-interactome degree distribution curve illustrates the quantity of nodes on the x-axis that bridged to the quantity of seeds (shown on the y-axis). The inter-interactome hubs (IIHs) are marked by a rectangle. (C) The IIHs with their associated number of bridged seeds and percent bridging are shown. *The protein UBC is reported but ignored given that it could indicate nonspecific ubiquitin binding to unrelated proteins marked for degradation (see15 for further information). (D) The network core (depicted in yellow) around the IIHs.

g:profiler Biological Pathway Analyses. Comparison of the g:Profiler functional enrichment performed for the entire weighted protein-protein interaction network analysis (W-PPI-NA) network (blue bars) and the core network (red bars). Gene ontology (GO) terms are reported on the y-axis and functional blocks are reported on the x-axis. The number on top of the bars indicates the percentage of overlap for each single functional block; the numbers in red indicate more than 12% of conservation (significant conservation). Each significant functional block is made of the semantic classes reported below the graph.

Discussion

Our analyses revealed a polygenic network of 64 svPPA risk genes which interact at the protein level. Many of these genes are differentially expressed in pathologically confirmed cases of FTLD with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (the same pathology most commonly seen in svPPA). Finally, we examined the biological pathways seen in this network and found significant enrichment in processing and metabolism of RNA as well as cell stress and apoptosis. These findings show that svPPA risk variants cluster in biological pathways representing processes closely tied to the primary protein pathology (TDP-43) seen in svPPA. Furthermore, our results suggest that further study of common genetic variation in svPPA could prove useful in the identification of individuals at risk for disease.

Our ontological pathway analysis showed the greatest degree of enrichment in pathways related to transcription and RNA metabolism. Converging evidence from multiple studies supports the role of RNA dysmetabolism in the pathogenesis of svPPA2,18,19,20. The most common protein pathology seen in svPPA is TDP-43 Type C2. TDP-43 is a protein heavily involved in RNA metabolic processes including transcription, splicing, and transport5. Thus, our finding of ontology enrichment in pathways related to RNA metabolism may be particularly relevant to svPPA which, in contrast to many other FTLD-spectrum disorders, is associated with a relatively low frequency of pathological accumulations of tau4. Recent work has shown that the RNA ribonuclear protein hnRNP E2 is associated specifically with TDP-43 immunoreactive neurites in svPPA, but not with other pathological FTLD subtypes21. Interestingly, 11 of our 64 genes for svPPA have been previously reported to have statistically significant co-expression profiles associated with hnRNP E2 (AKT1, GTF2B, MAML1, MDH1, RAD23A, RANGAP1, SMAD3, STAT6, TFDP1, UBE21, ZNHIT3)21. A number of these genes have been previously implicated in other TDP-43 proteinopathies without an svPPA syndrome. For example, in Drosophila RANGAP1 is a suppressor of neurotoxicity due to C9ORF72 pathogenic hexanucleotide repeat expansion22. Lastly, many of the genes in our svPPA network have been previously shown to be targets of neuronal TDP-43 ribonucleoprotein complexes, including AKT1, NOTCH1, and PSEN123.

Other biological pathways enriched in our analysis provided further support for a TDP proteinopathy-mediated mechanism of disease. For example, we observed enrichment in SMAD signaling pathways. SMAD proteins regulate the expression of target genes critical for regulating neuronal stability and apoptosis24. Previous work in mouse models has shown that TDP-43 aggregates co-localize with phosphorylated Smad proteins, which mediate downstream signaling in the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) pathway25. TGF-beta acts through the TGF-beta type II receptor that forms a complex with Activin, another pathway highly enriched in our Reactome pathway analysis. This pathway plays a role in a number of biological functions including neuronal development and homeostasis26,27. Furthermore, activation of TGF-beta and SMAD signaling has been shown to reduce mislocalized TDP-43 aggregate formation in human cell culture28. Lastly, Notch signaling pathways, including the gene NOTCH1, a key molecule regulating neuronal health and homeostasis, were significantly overrepresented in our svPPA risk gene network. Notch dysregulation has been previously reported as a mechanism of neurodegeneration seen in cases with PSEN1 mutations resulting in an FTD-like syndrome, though the pathology associated with these mutations is unreported29.

Our study benefits from its use of multiple publicly available, well-validated cohorts. The network analysis techniques used in this study rely upon previously validated experimental protein interaction data, which means the network interactions shown are ripe targets for cellular and molecular studies. This study is limited by a lack of additional GWAS data in which to replicate our genetic findings, but the anticipated release of IFGC phase III data will provide a suitable cohort for future confirmation and elaboration of these findings. The protein interaction analyses in our study rely heavily upon preexisting data and could therefore bias our findings towards the most studied biological pathways and processes. Additional studies focused on alternative ontological categories such as cellular components and molecular function may prove informative in future studies, but in our study the results of these ontological categories were judged as too general to be informative (data not shown). Unfortunately, the results of our VEGAS analyses do not facilitate the calculation of each gene’s, or the overall network’s, percent contribution to svPPA risk. Further molecular and model-organism studies will be required to validate and prove the importance of our svPPA network genes as modifiers of disease risk in svPPA and other TDP-43 proteinopathies. We attempted to replicate the protein interaction network results from our VEGAS analysis using differential expression data from GSE13162. The network generated using differential expression from GSE13162 was not significant after multiple testing correction (data not shown). This study focused on one of the FTLD phenotypes. Ongoing work in our group focuses on the other IFGC phenotypes30 as well as the work of other groups which will help to elucidate the genetic and biochemical pathways that make svPPA distinct from the other FTLD phenotypes and may further highlight which processes are shared across FTLD subtypes.

In summary, this study identified and bioinformatically characterized a network of 64 svPPA risk genes with interacting protein products. Many of these genes were differentially expressed in pathologically confirmed FTLD cases. Common variation in svPPA risk genes is implicated in RNA metabolism and cell death signaling. These findings are an important step towards a genetic understanding of what was previously considered a disease largely due to environmental and other risk factors.

Methods

Ethics, consent and permissions

This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the University of California, San Francisco Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board. The data collection from the original GWAS used in this analysis was overseen by the relevant institutional review boards, and ethics committees approved the research protocol of all individual studies used in the current analysis. Participants of those studies provided written informed consent.

svPPA gene network generation

To generate the svPPA network, we first calculated gene-level significance values using VEGAS10. This tool uses location information from the UCSC Genome Browser (hg18) assembly to assign individual SNPs to their respective gene. Gene boundaries were defined as 50 kb beyond the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of each gene to ensure we captured the effects of regulatory regions and SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD). VEGAS accounts for background LD patterns between markers within a gene using data from individuals of northern and western European descent (HapMap2 CEU)31. Monte-Carlo simulations use these LD patterns to generate a multivariate normal distribution which is used to calculate an empirical p-value for each gene. For additional details on VEGAS, please see Liu et al. and Baranzini et al.10,32.

We derived PINs from the iRefIndex database, a collection of 15 human PIN data sets from different sources33. The combined dataset from these PINs contained over 400,000 interactions among approximately 25,000 proteins. To minimize the number of false positives in our PIN, we limited our PIN to interactions described in at least two independent publications. The resulting network used as a background network in our analyses contained 8,960 proteins and 27,724 interactions. The PIN was uploaded into Cytoscape34 version 2.8.2 and used PINBPA to label each entry with genomic position, gene p-value, association block membership, and gene name (node attribute).

We computed significant first-order interactions by filtering the main network so that only the genes (and their protein products) with a VEGAS p-value less than 0.05 were retained. Following this, the number of resulting nodes and edges along with the size of the largest connected component were computed in Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/). We evaluated the network strength using permutations. The p-values from our VEGAS analyses were mixed randomly amongst genes and permuted networks to create a null distribution. The results of our svPPA network were compared against this null distribution. We evaluated the largest and most significant network to avoid false positive findings.

Gene expression in pathologically confirmed FTLD cases

We hypothesized that genes from our network analysis would be dysregulated in pathologically confirmed cases of FTLD as compared to controls. Given that svPPA is primarily associated with ubiquitinated inclusions composed of TDP-43, we chose to use a publicly available dataset of individuals diagnosed with FTLD with ubiquitinated inclusions and comparable control cases. Ten of the participants were pathologically diagnosed with sporadic FTLD and 11 diagnosed as controls (Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset GSE13162)35. In linear regression models we controlled for sex, post mortem interval, and age.

svPPA biological pathway enrichment analysis

We performed enrichment analyses on our genes of interest using the Reactome and GO annotation databases. Reactome (v60, released April 20th, 2017) is a curated pathway database that aggregates human pathways and reactions from UniProt, Ensembl, KEGG, GO, and PubMed, among others (http://www.reactome.org). We restricted the analysis to comparisons within the Homo sapiens annotations and ran the statistical enrichment tests for biological pathways under the default settings (which corrects for multiple testing using the Bonferroni technique).

To replicate the findings of our primary ontological analysis, we next applied the recently developed W-PPI-NA pipeline15 to increase resolution on the candidate proteins isolated by PINBPA. Specifically, we generated a second independent network using the svPPA genes prioritized by the PINBPA analysis by extracting (12 May 2017) their protein interactors (PPIs) from the following databases within the IMEX consortium17: APID Interactomes, BioGrid, bhf-ucl, InnateDB, InnateDB-All, IntAct, mentha, MINT, InnateDB-IMEx, UniProt, and MBInfo by means of the “PSICQUIC” R package (version 1.15.0 by Paul Shannon, http://code.google.com/p/psicquic/). PPIs were harmonized by converting Protein IDs to UniProt and Entrez IDs thus allowing merging of all databases. We removed TrEMBL, non-protein interactors (e.g. chemicals), obsolete Entrez, and Entrez matching to multiple Swiss-Prot identifiers. All PPIs underwent quality control and filtering leading to removal of: i) all the non-human taxid annotations, and ii) all the annotations with multiple or no PubMed identifiers or no description of Interaction Detection Method. The interactions were then scored as follows: (i) evaluation of the number of different publications reporting the interaction and (ii) evaluation of the number of different methods reporting the interaction. All the interactors with a final score ≤2 were discarded to reduce false positive rate. The final network was visualized using Cytoscape and analyzed through the network analysis plug-in. The inter-interactome degree distribution curve was drawn considering all the nodes within the network and the number of seeds they connect (number of node edges/number of network seeds = connection degree). We defined IIHs as any node connecting more than 15% of the seed’s interactomes.

As part of the W-PPI-NA, we applied functional annotation analysis to the network built using the PINBPA-prioritized genes as seeds. We then performed Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes (BPs) enrichment analyses through g:Profiler (g:GOSt,http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/)36, which runs Fisher’s one-tailed test and uses a set counts and sizes (SCS) based technique for multiple test correction. The statistical domain size was only annotated genes; no hierarchical filtering was included. We then grouped enriched GO-BP terms into custom-made “semantic classes” (Supplementary Data S2). We removed general, thus negligible, semantic classes such as general, metabolism, enzymes, protein modification, and physiology. Semantic classes were further grouped by similarity in more general classes called functional blocks.

Data Availability

Requests for GWAS metadata should be directed to the International FTD-Genomics Consortium. The PINBPA package is available through Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org). Reactome data is available at www.reactome.org. PANTHER data is available at www.pantherdb.org. The “PSICQUIC” R package (version 1.15.0 by Paul Shannon) is available at (http://code.google.com/p/psicquic/). g:Profiler is available at(g:GOSt,http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/).

References

Olney, N. T., Spina, S. & Miller, B. L. Frontotemporal Dementia. Neurol. Clin. 35, 339–374 (2017).

Landin-Romero, R., Tan, R., Hodges, J. R. & Kumfor, F. An update on semantic dementia: genetics, imaging, and pathology. Alzheimers. Res. Ther. 8, 52 (2016).

Gorno-Tempini, M. L. et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76, 1006–14 (2011).

Spinelli, E. G. et al. Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann. Neurol. 81, 430–443 (2017).

Lagier-Tourenne, C., Polymenidou, M. & Cleveland, D. W. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: Emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19 (2010).

Ferrari, R. et al. Frontotemporal dementia and its subtypes: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 13, 686–699 (2014).

Rohrer, J. D. et al. The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 73, 1451–1456 (2009).

Po, K. et al. Heritability in frontotemporal dementia: more missing pieces? J. Neurol. 261, 2170–2177 (2014).

Miller, Z. A. et al. Handedness and language learning disability differentially distribute in progressive aphasia variants. Brain 136, 3461–3473 (2013).

Liu, J. Z. et al. A versatile gene-based test for genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 139–145 (2010).

Gibson, G. Hints of hidden heritability in GWAS. Nat. Genet. 42, 558–560 (2010).

Neary, D. et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51, 1546–1554 (1998).

Fabregat, A. et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D649–D655 (2018).

The Gene Ontology Consortium. Expansion of the Gene Ontology knowledgebase and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D331–D338 (2017).

Ferrari, R., Lovering, R. C., Hardy, J., Lewis, P. A. & Manzoni, C. Weighted Protein Interaction Network Analysis of Frontotemporal Dementia. J. Proteome Res. 16 (2017).

Ferrari, R. et al. Stratification of candidate genes for Parkinson’s disease using weighted protein-protein interaction network analysis. BMC Genomics 19, 452 (2018).

Orchard, S. et al. Protein Interaction Data Curation -The International Molecular Exchange Consortium (IMEx). Nat Methods 161819, 345–350 (2012).

Rohrer, J. D. et al. TDP-43 subtypes are associated with distinct atrophy patterns in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 75, 2204–2211 (2010).

Cohen, T. J., Lee, V. M. Y. & Trojanowski, J. Q. TDP-43 functions and pathogenic mechanisms implicated in TDP-43 proteinopathies. Trends in Molecular Medicine 17, 659–667 (2011).

Miller, Z. A. et al. TDP-43 frontotemporal lobar degeneration and autoimmune disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 956–62 (2013).

Davidson, Y. S. et al. Heterogeneous ribonuclear protein E2 (hnRNP E2) is associated with TDP-43- immunoreactive neurites in Semantic Dementia but not with other TDP-43 pathological subtypes of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0454-4 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 56–61 (2015).

Sephton, C. F. et al. Identification of neuronal RNA targets of TDP-43-containing ribonucleoprotein complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1204–1215 (2011).

Schuster, N. & Krieglstein, K. Mechanisms of TGF-β-mediated apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 307, 1–14 (2002).

Nakamura, M. et al. Phosphorylated Smad2/3 immunoreactivity in sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and its mouse model. Acta Neuropathol. 115, 327–334 (2008).

Arber, C. et al. Activin A directs striatal projection neuron differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Development 142, 1375–1386 (2015).

Rodríguez-Martínez, G., Molina-Hernández, A. & Velasco, I. Activin a promotes neuronal differentiation of cerebrocortical neural progenitor cells. PLoS One 7 (2012).

Nakamura, M. et al. Activation of transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling reduces aggregate formation of mislocalized TAR DNA-binding protein-43. Neurodegener. Dis. 11, 182–193 (2013).

Amtul, Z. et al. A Presenilin 1 Mutation Associated with Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Inhibits γ-Secretase Cleavage of APP and Notch. Neurobiol. Dis. 9, 269–273 (2002).

Bonham, L. W. et al. Protein network analysis reveals selectively vulnerable regions and biological processes in FTD. Neurol. Genet. 4 (2018).

The International HapMap Corsortium. et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449, 851–61 (2007).

Baranzini, S. et al. Network-based multiple sclerosis pathway analysis with GWAS data from 15,000 cases and 30,000 controls. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 854–865 (2013).

Razick, S., Magklaras, G. & Donaldson, I. M. iRefIndex: A consolidated protein interaction database with provenance. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 405 (2008).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2498–2504, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Chen-Plotkin, A. S. et al. Variations in the progranulin gene affect global gene expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 1349–1362 (2008).

Reimand, J. et al. g:Profiler—a web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2016 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W83–W89 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Primary support for data analyses was provided by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) RMS1741 (LWB), Larry L. Hillblom Foundation 2016-A-005-SUP (JSY), AFTD Susan Marcus Memorial Fund Clinical Research Grant (JSY), NIA K01 AG049152 (JSY), Bluefield Project to Cure FTD (JSY), Tau Consortium (JSY), NIA K01 AG046374 (CMK), U24DA041123 (RSD), National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Junior Investigator Award (RSD), RSNA Resident/Fellow Grant (RSD), Foundation of ASNR Alzheimer’s Imaging Grant (RSD), and Alzheimer’s Society Grant 284 (RF). Additional support was provided by an MRC Programme grant (MR/N026004/1; JH and PAL) and a MRC New Investigator Research Grant (MR/L010933/1; PAL). PAL is a Parkinson’s UK research fellow (grant F1002). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank the International FTD-Genomics Consortium (IFGC) for providing phase I summary statistics data for these analyses. Further acknowledgments for IFGC, e.g. full members list and affiliations, are found in the online supplementary files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

IFGC acknowledgements and full collaborator list are provided after the reference section

Consortia

Contributions

L.W.B., N.Z.R.S., J.S.Y., S.E.B., C.M.K., R.S.D., C.M. and R.F. designed the study. L.W.B., N.Z.R.S., E.G.G., I.B., N.L.W., C.P.H., J.H., R.F., P.M., I.F.G.C., Z.A.M., M.G.T., B.L.M. and W.W.S. acquired the data. L.W.B., N.Z.R.S., N.L.W., C.M.K., R.F., C.M., P.L. and P.A. analyzed the data. L.W.B., N.Z.R.S., C.M.K., R.F., C.M., P.A., W.W.S., R.S.D. and J.S.Y. interpreted the data. L.W.B., N.Z.R.S., J.S.Y., R.F., C.M. and P.A. drafted the initial manuscript and all authors were involved in critical feedback and revisions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonham, L.W., Steele, N.Z.R., Karch, C.M. et al. Genetic variation across RNA metabolism and cell death gene networks is implicated in the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Sci Rep 9, 10854 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46415-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46415-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.