Abstract

Aims

To investigate potential factors associated with the presence of myopia in a cohort of young adult men carrying out their military service in Greece.

Methods

A nested case–control study of 200 conscripts (99 myopes and 101 non-myopes). The cohort consisted of approximately 1000 conscripts in compulsory national service. All cohort members had been screened for refractive errors by Snellen visual acuity measurement at presentation to military service; individuals not achieving visual activity 6/6 underwent noncycloplaegic refraction. The study sample consisted of the first 99 myopic and 101 nonmyopic conscripts who attended the study. In-person interviews of these 200 conscripts were conducted to obtain information on family history, occupation, level of education, near-work activities, and sleeping behaviour. χ2 and Mann–Whitney tests were used as univariate analysis methods to identify the potential factors associated with the presence of myopia. Multiple logistic regression was used to estimate the adjusted relative risk of myopia.

Results

Univariate analysis showed that parental family history (P<0.001), older age (P<0.001), tertiary education (P<0.001), hours of reading per day (P<0.001), hours of computer use per day (P<0.001), and higher social classes (P<0.001) were associated with myopia. Sleeping in artificial or ambient light was not associated with myopia (P=0.75). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that older age (OR=1.25, 95% CI 1.05–1.49), tertiary education (OR=12.67, 95% CI 3.57–44.88) and parental family history (OR=3.39, 95% CI 1.56–7.36) were independently associated with myopia.

Conclusion

In young Greek conscripts, parental family history, older age, and education level are independently associated with myopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

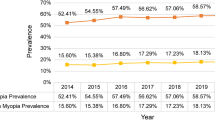

Myopia is the most common refractive error among young adults.1, 2 The aetiology of myopia is considered multifactorial with a tight interaction between genetic and environmental factors.3 Twin studies have shown that myopia has a major genetic component and many studies have linked myopia to near work and years of education.2, 4, 5, 6, 7 Reduced daily exposure to darkness has also been identified as a potential risk factor in both adults and children under the age of 2 years.8, 9

Data concerning risk factors of myopia in Greek individuals is limited. Medline search of the literature showed only one study on the epidemiology and risk factors of myopia in Greece.10 This had been carried out on 15–18-year-old students. The aim of our study was to investigate potential factors associated with the presence of myopia in a slightly older cohort of young adult men carrying out their compulsory military service in Greece.

Materials and methods

Study population

A nested case–control study was carried out between March 2002 and May 2003 at a military camp in Northern Greece. The cohort consisted of approximately 1000 conscripts who were carrying out their compulsory national service in the Greek army. At their initial presentation to the camp, all conscripts were invited to participate in the study. Interested individuals subsequently attended the surgery for an interview. Our study sample consisted of the first 99 individuals with myopia and the first 101 with no myopia who attended for the purposes of the study. Informed consent and approval from the appropriate military board were obtained. All conscripts were Caucasian's of a random social mix and came from either urban or rural areas of Greece.

At their initial health assessment, all cohort members, about 1000 conscripts, were screened for refractive errors by an ophthalmologist; those not achieving Snellen visual acuity 6/6 underwent noncycloplaegic refraction. At this stage, individuals with significant ocular problems were excluded from military service and, therefore, from our study. The exclusion criteria applied include refractive error greater than 18 dioptres sphere (DS) in both eyes or greater than 9 DS in both eyes if associated with significant maculopathy, and best-corrected visual acuity less than 6/18 in both eyes or less than 6/60 in one eye if greater than 6/15 in the other eye.

Questionnaire

An in-person interview was carried out and a standard questionnaire used. Questions concerning family history, social class, education level, amount of near-work activity (number of hours per day), and sleeping behaviour (number of hours per day and whether in absolute darkness) were included. Near-work activity and sleeping behaviour concerned the previous 4 years of the individual. The refraction recorded was the most up to date provided by the conscript and his records. The lower cutoff point for inclusion in the myopic group was set at a mean spherical equivalent of –0.50 DS for the two eyes. Individuals achieving unaided Snellen visual acuity 6/6 in both eyes at the initial screening were allocated to the nonmyopic group.

Data analysis

Social class was recorded according to the UK Registrar General's class scheme.11 In order to facilitate data analysis, social classes I, II, and III nonmanual (IIIN) were grouped together as higher social classes, whereas III manual (IIIM), IV, and V as lower social classes. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version 9). The outcome of interest was the presence of myopia. χ2 and Mann–Whitney tests were used to identify the potential factors that can be associated with the presence of myopia and multiple logistic regression analysis to identify the independent factors.

Results

The results are detailed in Table 1. The median age of myopes was 23 years compared to 19 years of nonmyopes (P<0.001). In the group of myopes, 45.5% had at least one parent with myopia, compared to only 17.8% in the nonmyopes (P<0.001). The presence of two myopic parents was not significantly different in myopes and nonmyopes (7.1 vs 3.0%, P=0.20). A significantly larger proportion of myopes belonged to the upper social classes compared to nonmyopes (58.6% vs 16.8%, P<0.001).

In the group of myopes, 56.6% had attended tertiary education, compared to only 4% in the nonmyopes (P<0.001). Myopes spent more hours per day reading than nonmyopes (P<0.001); mean spherical equivalent correlated poorly with hours of reading per day (correlation coefficient 0.07). Myopes also used a computer significantly more (P<0.001). Total TV viewing per day, use of TV video games, and sleeping behaviour were not significantly different in the two groups.

We used multiple logistic regression analysis to model myopia predicted by parental family history, tertiary education, amount of reading per day, computer use per day, social class, and age. Age, parental family history, and tertiary education maintained an independent association (Table 2).

Discussion

National military service is required for all Greek men, either before or upon completion of their tertiary education. Conscript allocation to camps is random via a process that aims to avoid discrimination against conscripts from rural areas of Greece or from lower socioeconomic classes. Individuals with significant health problems, including ocular conditions, are excluded from national service.

We found that older age was independently associated with myopia. It has shown that up to the age of 25 years, the prevalence of myopia increases with age.12 Exposure to factors potentially associated with myopia, such as reading, over a prolonged period of time may lead to the development of myopia, explaining the association of myopia with older age. This may be particularly true for adults of the age group in our study, as at this age the eye can still elongate. Axial elongation of the globe has been shown to be the basic oculometric event in myopia of adult onset.13 In addition, in longitudinal cohort studies of university students, all exposed to similar environmental stimuli, the prevalence of myopia increased significantly during the course of the degree.8, 14

A positive parental family history, with at least one myopic parent, was also independently associated with myopia. The presence of at least one myopic parent was significantly higher in myopes compared to nonmyopes (45.5 vs 17.8%). The presence of two myopic parents was also higher in myopes (7.1 vs 3.0%), but the difference was not statistically significant. This could be due to the small sample size. Both factors, at least one myopic parent and two myopic parents, were approximately 2.5 times more common in the myopic group. The influence of genetic factors on the development of myopia has been supported by twin studies.4, 15, 16 The only other study on myopia carried out in Greece also supported the association of parental family history with myopia.10 However, Saw et al17 showed that, although parental myopia was significantly related to offspring myopia, the relationship became nonsignificant when adjusted for educational level and other environmental factors.

In our study, tertiary education was independently associated with the presence of myopia. Many studies have linked myopia to the years of education.2, 5, 7 Wensor et al5 found a significant relationship between education level and myopia, with the prevalence of myopia increasing with higher degrees of education. In Singapore military conscripts, education and educational variables have been shown to correlate with myopia, with a multivariate adjusted odds ratio of 4.1 for myopic conscripts with preuniversity or tertiary education.17 The effect of tertiary education in our study appears to be larger than previously published.2, 17 Educated myopes may have been overrepresented in our study sample compared to the cohort. An explanation for this possible bias could be that, owing to the voluntary attendance for the study, educated myopes were more likely to volunteer and attend the study than noneducated myopes. Educated individuals have a better understanding of the concept of research and are possibly more likely to turn up for a study in their free time rather than participate in ongoing leisure activities.

Education level could be considered a surrogate of factors associated with myopia, such as socioeconomic background, intelligence, and near-work activity.17 Our study showed that, although myopes did read significantly more per day than non-myopes, the amount of reading per day did not remain an independent association. The degree of myopia also correlated poorly with hours of reading per day. An actual association of myopia with near work has repeatedly been difficult to prove.18 In Singapore conscripts, close-up work activity has been shown not to be different in high, low, and nonmyopes.17 A possible explanation could be that retrospective recall and assessment of near-work activity by self-reported questionnaires may not be accurate enough. Alternatively, the total amount of near work per day may not be the most crucial risk factor for development of myopia. Other aspects of near work, such as duration of activity without a ‘significant’ period of break and relaxation of accommodative effort, may be more important. Factors not assessed in this study, such as intelligence, may also be affecting the relationship of myopia to near-work activity and tertiary education. But retrospective estimates of such parameters are difficult and possibly inaccurate.

TV viewing, TV console games, and computer use were not independently associated with the presence of myopia. Although myopes did use the computer for more hours per day than nonmyopes, this association did not persist when confounders were controlled for. Most studies have found no relationship between the development of myopia and computer use or TV viewing.19, 20

Our study did not show an association of myopia with exposure to artificial or ambient light overnight. Reduced exposure to darkness, and thus prolonged exposure to light is considered a potential risk factor for myopia. Loman et al,8 looking at adult students, found that reduced daily exposure to darkness was significantly associated with myopia progression. A positive association has also been described in children. Quinn et al,9 looking at children, showed that the prevalence of myopia during childhood was strongly associated with ambient light exposure during sleep at night in the first 2 years after birth. However, this study did not control for potential confounding factors such as parental myopia and near-work activity. More recent studies that looked into such factors did not support such an association.21, 22

A larger proportion of myopes belonged to the upper social classes than nonmyopes. In an Australian study, professionals and clerks were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of myopia than other occupational groups.5 Shimizu et al2 showed that the presence of myopia was associated with management occupations in men, and with clerical and sales/service occupations in women. Although in our study higher social class was associated with myopia, social class did not remain an independent association when other factors were controlled for. The strong link of tertiary education with higher social class could possibly explain this.

We carried out a nested case–control study based on a cohort of 1000 conscripts. A major challenge in the design of a case–control study is the appropriate selection of controls.23 The selection process in our study consisted of including the first 100 myopes and first 100 nonmyopes who presented voluntarily for the purposes of the study. As discussed above, this may have overestimated the effect of education as an association with myopia. In an ideal situation, we would have interviewed all myopes and nonmyopes in the cohort, but this was not possible.

Our study models the odds ratios associated with being a myope rather that becoming a myope. In an attempt to minimise the inaccuracies associated with recall bias, rather than question activities in childhood, we concentrated on behavioural patterns relating to the previous 4 years of the individual, as these were more likely to be estimated and recalled accurately. The results may potentially be confounded by childhood activities, but ascertaining such information retrospectively and controlling for accurately is difficult. In Singapore conscripts, childhood near-work activity, assessed by retrospective recall, was not different in myopes and nonmyopes.17 Another limitation of our study, as of most retrospective epidemiological studies, is that results may be subject to recall bias. Myopic conscripts are more likely to know whether their parents are myopic than nonmyopic conscripts.

In conclusion, our study identified older age, parental family history, and tertiary education as independent factors associated with the presence of myopia in young Greek conscripts. Our findings provide evidence to the multifactorial nature of myopia in young adult men in Greece.

References

Midelfart A, Kinge B, Midelfart S, Lydersen S . Prevalence of refractive errors in young and middle-aged adults in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2002; 80: 501–505.

Shimizu N, Nomura H, Ando F, Niino N, Miyake Y, Shimokata H . Refractive errors and factors associated with myopia in an adult Japanese population. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2003; 47: 6–12.

Feldkamper M, Schaeffel F . Interactions of genes and environment in myopia. Dev Ophthalmol 2003; 37: 34–49.

Hammond CJ, Snieder H, Gilbert CE, Spector TD . Genes and environment in refractive errors: The twin eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001; 42: 1232–1236.

Wensor M, McCarty CA, Taylor HR . Prevalence and risk factors of myopia in Victoria, Australia. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 658–663.

Katz J, Tielsch JM, Sommer A . Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in an adult inner city population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997; 38: 334–340.

Wang Q, Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE . Refractive status in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994; 35: 4344–4347.

Loman J, Quinn GE, Kamoun L, Ying GS, Maguire MG, Hudesman D et al. Darkness and near work activity: myopia and its progression in third year law students. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 1032–1038.

Quinn GE, Shin CH, Maguire MG, Stone RA . Myopia and ambient lighting at night. Nature 1999; 399: 113–114.

Mavracanas TA, Mandalos A, Peios D, Golias V, Megalou K, Gregoriadou A et al. Prevalence of myopia in a sample of Greek students. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000; 78: 656–659.

OPCS. Standard Occupational Classification, Vol 3.HMSO: London 1991.

Sperduto RD, Seigel D, Roberts J, Rowland M . Prevalence of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 1983; 101: 405–407.

Fledelius HC . Adult onset myopia-oculometric features. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1995; 73: 397–401.

Kinge B, Midelfart A . Refractive changes among Norwegian university students. A three-year longitudinal study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1999; 77: 302–305.

Teikari JM, O'Donnell J, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M . Impact of heredity on myopia. Hum Hered 1991; 41: 151–156.

Hu D . Twin studies on myopia. Chinese Med J 1981; 94: 51–55.

Saw SM, Wu HM, Seet B, Wong TY, Yap E, Chia KS et al. Academic achievement, close up work parameters, and myopia in Singapore military conscripts. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 855–860.

Mutti DO, Mitchell LG, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K . Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children's refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43: 3633–3640.

Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G, Rystad J . The influence of near work on development of myopia among university students. A three-year longitudinal study among engineering students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000; 78: 26–29.

Mutti DO, Zadnik K . Is computer use a risk factor for myopia? J Am Optom Assoc 1996; 67: 521–530.

Saw SM, Zhang MZ, Hong RZ, Fu ZF, Pang MH, Tan DTH . Near-work activity, night-lights, and myopia in the Singapore–China study. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 620–627.

Saw SM, Wu HM, Hong CY, Chua WH, Chia KS, Tan D . Myopia and night lighting in children in Singapore. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 527–528.

Wacholder S, McLaughlin JK, Silverman DT . Selection of controls in case control studies: I: principles. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 135: 1019–1028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

No proprietary interest or funding involved. Part of paper presented as poster at XXII Congress of ESCRS, Paris 2004

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konstantopoulos, A., Yadegarfar, G. & Elgohary, M. Near work, education, family history, and myopia in Greek conscripts. Eye 22, 542–546 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702693

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702693

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of reading with a mobile phone and text on accommodation in young adults

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Continuous Objective Assessment of Near Work

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Effect of pregnancy in myopia progression: the SUN cohort

Eye (2017)