Abstract

Hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites have attractive optoelectronic properties including exceptional solar cell performance. The improved properties of perovskites have been attributed to polaronic effects involving stabilization of localized charge character by structural deformations and polarizations. Here we examine the Pb–I structural dynamics leading to polaron formation in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite by transient absorption, time-domain Raman spectroscopy, and density functional theory. Methylammonium lead iodide perovskite exhibits excited-state coherent nuclear wave packets oscillating at ~20, ~43, and ~75 cm−1 which involve skeletal bending, in-plane bending, and c-axis stretching of the I–Pb–I bonds, respectively. The amplitudes of these wave packet motions report on the magnitude of the excited-state structural changes, in particular, the formation of a bent and elongated octahedral PbI64− geometry. We have predicted the excited-state geometry and structural changes between the neutral and polaron states using a normal-mode projection method, which supports and rationalizes the experimental results. This study reveals the polaron formation via nuclear dynamics that may be important for efficient charge separation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites (HOIP) composed of an organic cation and inorganic framework are one of the most promising new solar cell materials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. These materials are exciting because of their high power conversion efficiency (PCE) as well as their low-cost and facile fabrication11. Their efficiency has reached ~23% which is now comparable with single crystalline silicon-based solar cells12. However, understanding the underlying mechanisms of this high PCE is still a significant challenge.

Polycrystalline HOIP fabricated at low temperatures (~100 °C) has significant crystalline inhomogeneity: defects and grain boundaries typically introduce multiple energy-loss trap sites that may significantly lower the PCE13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. This inhomogeneity is surprising because most other inorganic solar cell materials require pure crystalline composition for high PCEs21,22. Altogether these observations suggest that the inhomogeneity in the polycrystalline HOIP does not greatly influence the performance by protecting free charge carriers from ultrafast thermal relaxation, although these defects do accumulate in humidity-degraded materials23,24,25. Associated with the high PCE, polycrystalline HOIP exhibits a long lifetime (τ~1−3 μs) and a long diffusion length (LD~1−3 μm), as well as modest mobility (μ~30−100 cm2 V−1 S−1) for the free charge-carriers26,27,28. These characteristics indicate the efficient suppression of unfavorable ultrafast charge-recombination and suggest that unique excited-state dynamics may enable the longer charge-carrier lifetime and their impunity to thermal relaxation29.

The formation of a polaron, a charged quasi-particle, may account for the unique excited-state photo-physical properties in HOIP30,31. In principle, the charge-localized polaron state is energetically unstable without further stabilization. Once it is formed in a higher energy state, it should quickly relax via high energy phonon scattering32. However, polaron formation in HOIP can be favorable; electric dipole reorientation of the nearby organic cations not only minimizes the Gibbs free energy of the polaron but also protects the charges from other ultrafast thermal relaxations according to Zhu and coworkers29,32,33. They have successfully measured femtosecond time-resolved fluorescence of the hot electron–polaron in methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) and shown that after a few hundred femtosecond relaxation, which is related to the methylammonium (MA) cation reorientation time, the polaron lives as long as ~100 ps24.

We have recently reported a theoretical prediction on the structure of the small electron polaron of MAPbI3, which exhibits not only MA dipole reorientations toward the charge but also the structural distortion of the inorganic Pb–I framework to stabilize the isolated charge34. In particular, the structural distortion associated with a polaron suggests that ground and excited-state potential energy surfaces (PES) have different energy minima along nuclear coordinates that are related to the distortion. Thus, coupled electron–phonon dynamics can be coherently excited on the polaron PES by impulsive excitation, where the associated reorganization energies (λ) and displacements (Δ) determine the polaron formation pathways35,36. These coherent dynamics have been detected by using femtosecond time-resolved spectroscopies37,38. For example, Wang et al.39 recently observed a single coherent wave packet oscillating at ~23 cm−1 in a MAPbI3 film using femtosecond transient absorption. However, additional experimental studies of excited-state dynamics in HOIP are necessary to resolve higher frequency vibrations disclosing the structural dynamics of polaron formation.

Herein, we report the production and analysis of coherent nuclear wave packets in MAPbI3 that oscillate at low frequencies ( < 100 cm−1) as measured by femtosecond impulsive stimulated-Raman spectroscopy (ISRS). We also present first principles density functional theory (DFT) simulations of the structural distortions associated with polaron state. The PbI64− octahedral charge-state geometry changes based on the experimental excited-state Raman displacements and the theoretical simulation are then compared. These results reveal coherent Pb–I vibrational normal mode dynamics that lead to the stabilized polaron state.

Results

Coherent wave packet measurement and analysis

We probed the transient excited-state absorption (ESA) band of MAPbI3 perovskite in the near infrared (NIR) wavelength (830−940 nm) region which is distinct from the ground-state absorption (GSA), stimulated emission (SE) and other bleach bands (see Methods). Fig. 1a presents the contour plot of the ESA band centered at ~855 nm. There are no dynamic peak growths or shifts after the response-limited appearance; the ESA simply shows an exponential intensity decay in the observation window. Three representative time-profiles in the 840–855, 860–875, and 885–900 nm region are presented in Fig. 1b–d. The rise times are all resolution limited and each decay is well fit by a biexponential decay with constants of ~240 fs and 3.8–5.1 ps. Especially, the fits to the red and blue traces suggest that these data also contain underlying temporal oscillations. The difference residuals between the exponential fits and the experimental data in Fig. 1 confirm the existence of these temporal oscillatory components that are likely due to coherent nuclear wave packet dynamics.

Transient excited state absorption spectrum shown in the 830–940 nm region of MAPbI3 perovskite excited by a ~40 fs FWHM pulse at 560 nm. a Contour plot of excited state absorption band centered at ~855 nm. b–d Time profiles measured at 840–855 (blue), 860–875 (green), and 885–900 nm (red) fit to the sum of two exponentials with the indicated constants. The residual profiles are also shown revealing underlying oscillations especially in the 840−855 and 885−900 nm regions

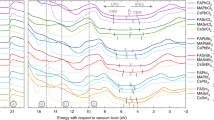

Fast Fourier transform (FFT) and linear prediction with singular value decomposition (LPSVD) analyses were performed to quantitate the oscillatory components in the NIR ESA band. The FFT spectra are presented from the residuals extracted from the exponential fittings at each wavelength (Fig. 2a), which mostly exhibit Raman modes lower than 150 cm−1. The FFT spectral intensities exhibit a bi-lobed pattern with strong components below 860 nm and above 880 nm but weak amplitudes around 865 nm near the ESA maximum (Supplementary Fig. 1). This result is consistent with the expectation that when a spectral band position is oscillating in time, the largest signal differences are on the red and blue sides, where the slope is highest and the lowest amplitude oscillations are near the peak center40,41. Figure 2b, c presents FFT and LPSVD results extracted in the indicated blue and red regions, which both exhibit common low frequency modes at ~20, ~43, and ~75 cm−1, supporting our wave packet analysis. In addition, the FFT spectra reveal very small 110 and 150 cm−1 Raman peaks which were also found in our previous resonance Raman studies42, but we were unable to perform a more detailed analysis of the latter bands here because of their weak intensities.

FFT spectra of Fig. 1. a Contour plot of FFT spectra measured in the entire probe pulse range for MAPbI3 perovskite (830–940 nm). b, c FFT and LPSVD spectra measured at 840–855 nm (blue) and at 885–900 nm (red). d Display of the relative phases of the three principal LPSVD peaks fit on the red and blue sides of the band

To examine whether these oscillatory signals are indeed due to band position oscillation of the ESA band we examined the relative phase of these oscillations. In principle, for the band position shift model they should be ~180° out of phase. However, it is sometimes difficult to extract the ideal phases and frequencies when there are highly damped and mixed oscillations with other frequencies. This ambiguity may result in serious overestimation using LPSVD analysis. In order to avoid this error, we cross-checked both the FFT and LPSVD results, as shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3d presents the phase parameters for the ~20, ~43, and ~75 cm−1 modes from the LPSVD results. The most intense wave packet at ~20 cm−1 has the largest phase shift from 150° to 0° which is nearly out of phase as expected. The 45 and 75 cm−1 modes exhibit relative phases of 240/170 and 140/80 on the red/blue sides that are roughly 60–70° out of phase. The deviation from the expected 180° phase differences might result from the somewhat larger errors in these phase determinations than for the 20 cm−1 mode. Especially, the ~180° out of phase features of the strongest ~20 cm−1 mode together with the amplitude pattern in Fig. 2a, support the idea that these signals are due to coherent nuclear wave packets which are propagating on the excited-state PES.

DFT calculated vibrational modes of MAPbI3. a Skeletal I–Pb–I bending motion of the PbI64− octahedron at 25.6 cm−1. b I–Pb–I bending motion on the ab-plane at 49.3 cm−1. c Pb–I c-axis stretching motion at 82.0 cm−1. Red arrows on the atoms indicate the direction and relative amplitude of displacements in the given vibrational modes

Vibrational Raman mode calculation

To identify the vibrational modes associated with the observed wave packets, DFT calculations of vibrational normal modes in the room temperature tetragonal (I4/mcm) phase of MAPbI3 were performed using periodic boundary conditions (see Methods)42. Figure 3 presents the vibrational displacements (red arrows) calculated for the 25.6, 49.3, and 82.9 cm−1 modes of ground state MAPbI3 perovskite energetically lying in the region of interest. These vibrational modes are mostly composed of I−Pb−I bond bending and stretching motions unlike other higher frequency Raman modes above ~100 cm−1 which involve MA motion42. Figure 3a depicts a large I–Pb–I bending motion at 25.6 cm−1 which can be described as a B1g mode in \({\mathrm{D}}_{4{\mathrm{h}}}^{18}\) symmetry group (I4/mcm) space group, while Fig. 3b presents another I–Pb–I bending motion in the ab-plane at 49.3 cm−1 (A1g mode in \({\mathrm{D}}_{4{\mathrm{h}}}^{18}\)). On the other hand, the 82.9 cm−1 mode in Fig. 3(c) displays the c-axis Pb–I stretching displacement (A1g in \({\mathrm{D}}_{4{\mathrm{h}}}^{18}\)) that effectively modulates the height of the octahedral cell. Based on the reasonable assumption that low frequency skeletal modes are similar in the ground and excited state, these three vibrational modes can be assigned to the experimentally measured wave packet modes at 21, 43, and 75 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 2) and used to depict distortion pathways of the octahedral PbI64− structure in the excited-state. Some disagreement between the DFT simulations and experiment is expected for low-frequency vibrational modes (here ~18, 9.0, and 9.0% for three modes in question) due to the shallow potential energy surface and the harmonic approximation used for analysis. For example, a recent study compared IR absorption and DFT results showing ~20% deviations in < 100 cm−1 region43. Thus, to reduce the discrepancy, we previously considered several additional effects that need to be taken into account to properly compare calculations with experiments which improved the reliability of our assignments42.

Polaron state geometry calculation

To theoretically simulate the structural changes of excited PbI64− DFT simulations of finite clusters of MAPbI3 perovskites were performed following procedures previously outlined in our recent work34. The subsequent analysis is based on CAM-B3LYP functional (see our previous work34 and Methods). Specifically, we obtained geometries of a MAPbI3 neutral cluster and a cluster with an extra electron mimicking negative polaron generation. The computationally determined ground state structure was previously verified by XRD experiments, and is therefore more reliable compared to the geometry of charged states34. Figure 4 shows the structurally optimized clusters of the simulated neutral and negative polaron states of MAPbI3 perovskite. In the polaron structure, the methylammonium counterions reorient their electric dipoles (indicated by red arrows) toward the center Pb atom to minimize the free energy of the localized electron density in the center Pb atom34. In addition, the Pb–I bonds, especially in the central PbI64− octahedra, also experience substantial structural changes, when an electron is added. Figure 4c compares the central PbI64− octahedron structure of the neutral (Sneu, red sphere) and the polaron (Spol, blue sphere). The most unique structural difference between Sneu and Spol is the octahedron height along z-axis; the polaron PbI64− has a Pb–I(5) distance of 4.2 Å which is considerable longer than 3.3 Å for the neutral one. In addition, the neutral PbI64− has a nearly right angle (89°) for the I(5)–Pb–I(4) bond, while in the polaron the bond angle is 84°. Thus, the polaron has a distorted and bent octahedral structure, while the neutral geometry forms a nearly regular octahedron. These differences are indicated by the displacement vectors (green arrows) in Fig. 4c, which are composed of bending and stretching motions of the I–Pb–I bond.

Theoretically predicted cluster structures of MAPbI3 perovskite. a Neutral cluster. b Polaron (−1) cluster. c Various perspective comparisons of the neutral (red sphere) and polaron (blue sphere) PbI64− octahedral structures centered in the clusters. The structural comparison shows that the polaron state geometry is more bent and elongated than the neutral, indicated by displacement vectors (green arrows)

The structural differences predicted for the excited polaron state geometry should be related to the vibrational relaxation toward the charge state minimum that occurs after Franck–Condon (FC) excitation of the neutral form. Thus, the measured vibrational modes oscillating in the ESA should be the modes that trigger the nuclear reorganization that forms the excited polaron state. In order to test this hypothesis, we quantitatively investigated the relation between the experimental excited-state vibrational oscillation intensities (Figs. 1–3) and the polaron structural predictions (Fig. 4).

Experimental and theoretical displacement analysis

The key part of our analysis is relating the oscillatory signals in the ESA in Figs. 1 and 2 with the displacement of the excited state of perovskite along the observed vibrational modes. In the time-dependent picture of Raman intensities, these excited state oscillations are precisely the nuclear motions that give rise to the resonance Raman scattering process. Since the Raman scattering cross-sections (σR) are approximately proportional to ∆2ω2 in the short-time limit, where ∆ and ω are the ground-to-excited state displacement of the potential minima and the vibration frequency, respectively44,45,46, the relative displacement ratio for each Raman peak can be determined. Using this relationship, the relative displacement ratio (∆Exp) is found to be ±4.3, ±1.4, and ±1.0 for the ~20, ~45, and ~75 cm−1 modes in the impulsive stimulated Raman spectra (ISRS) in Fig. 2. The absolute phases cannot be determined from the experimental data alone because of the ∆2 relationship. The ∆Exp result shows that the I–Pb–I bending motion at ~20 cm−1 is the most highly displaced vibrational normal mode, and thus, the most responsible for the excited-state PES deformation that we have probed in the TA. The other bending and stretching modes provide lower displacement contributions to the excited-state PES. Thus, using the ∆Exp, we can experimentally estimate a polaron state structure (SExp) given by

where p is a proportional factor and \({\mathbf{C}}_{{\mathrm{neu}}}\) is a matrix containing the Cartesian-coordinate vibration eigenvectors of each atom of the neutral state. Notably, Eq. (1) does not rely on the less accurate theoretical Spol for excited state structure. Figure 5a presents the comparison of Sneu (red), Spol (blue), and SExp (green) with p = 1.6 from the best nonlinear square fit toward Spol (\({\boldsymbol{\chi }}_r^2\)~1.43) when 4.3, 1.4, and −1.0 are used for \({{\Delta }}_{{\mathrm{Exp}}}\). We determined the phases of the \({{\Delta }}_{{\mathrm{Exp}}}\) from inspection of the theoretical polaron geometry in Fig. 4b. It is evident that the green atoms of the reconstructed SExp move toward the blue (Spol) from the red (Sneu) locations, thus affirming the successful simulation of the theoretically observed polaron state structure using the relative displacement ratio, ∆Exp.

Structural comparisons between experiment and theory. a Reconstructed PbI64− octahedral structure (green) from ∆Exp and Eq. (1) compared with the theoretically predicted neutral (red) and polaron (blue) state structures. b Displacement comparisons between the experiment (∆Exp) and theory (∆Theo)

A complementary approach for analyzing these geometric changes is to perform a normal mode projection from the Sneu to Spol by relying solely on theoretical predictions47. The theoretical displacement (∆Theo) is given by

where l is a diagonal matrix containing \(l_{ii} = \left( {\frac{\hbar }{{2\pi \nu _i}}} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\), and \(\nu _i\) is the ith vibration frequency. ΔTheo are determined to be +2.8, +0.3, and −5.1 for the 20, 45, and 75 cm−1 vibration modes, respectively. In addition, the excited-state reorganization energy (λ) is calculated to be 145 meV (~1170 cm−1) given by \({\mathit {\lambda }} = \frac{h}{2}{\sum} {\nu _i{{\Delta }}_i^2}\), where h is Planck constant. This value is very consistent with the band gap stabilization energy (~160 meV) found in a periodic boundary condition (PBC) DFT calculation34, indicating that our observed vibration modes represent the majority of polaron stabilization dynamics.

Figure 5 shows that the combined ∆Exp and ∆Theo results are in good qualitative agreement; both experimental and theoretical displacements show that the 20 cm−1 displacement is larger than the 45 cm−1 displacement, both confirming that the whole octahedral I–Pb–I bending motion at ~20 cm−1 provides strong displacements toward the polaron state. However, the displacement −5.1 of 75 cm−1 mode of ΔTheo is larger than the experimentally observed ΔExp at 75 cm−1. This inconsistency principally results from the different heights of Spol (4.2 Å) and SExp (3.6 Å) which result from an overestimation of Spol due to the use of limited atom numbers in the calculation and an underestimation of Sexp due to the limited time-resolution of the experiment which damps the oscillatory signal strength for the higher frequency mode. However, both our methods (Eqs. (1) and (2)) present a consistent picture about the elevated octahedral heights from Sneu. Thus, the theoretically predicted polaron geometry is nicely supported by the experimentally resolved vibrational displacements, showing that I–Pb–I bending and stretching motions are the key displacements stabilizing polaron formation.

Discussion

Our nuclear wave packet results and theoretical simulations on MAPbI3 perovskite show how the polaron state is coherently generated on the displaced PES. Electronic excitation above the band gap (~1.65 eV) of MAPbI3 produces the coherences as determined in the current study, ultimately leading to the separation of an initial excitation into free charges in view of weak excitonic effects in MAPbI348,49. The observed dynamic vibrational excitations facilitate this relaxation toward different structures, where a localized charge is further stabilized through the structural deformation of the Pb–I framework (Fig. 4) and the MA electric dipole reorientation; this is the polaron state hypothesis34. The reorientation time (τ) of the solvated MA was measured to be ~150 fs by using optical Kerr-gate spectroscopy and ultrafast IR spectroscopy; this time is most relevant for ultrafast coherent solvation in solutions33,50. In this context, we have found small FFT peaks at ~150 cm−1 (see Figs. 1 and 2) which are likely due to MA’s libration motion42. However, the MA coherence is found to be much smaller than the Pb–I coherences, showing that the Pb–I motions present the principal FFT peaks at low frequencies. This suggests that the MA reorientational motion is likely to be a more continuous (incoherent) solvent-like movement stabilizing the localized polaron50, while the measured Pb–I vibrations are coherent processes which trigger the Jahn–Teller distortion.

Pb and I atoms are covalently bonded to form the sturdy perovskite framework. However, once more charge character is introduced (especially, into the Pb atom), this Pb–I framework becomes more ionic51 and the transition is facilitated by Pb–I structural distortions shown as the bending and elongations of the Pb–I bonds mirrored in our theoretical studies (Fig. 4). Our key finding is that this distortion is effectively performed by Pb–I coherent vibrational motions over a few picosecond time scale. Interestingly, both experiment and theory agree that the 21 cm−1 mode (I–Pb–I bending) should be the principal nuclear distortion motion for polaron formation, in good agreement with the strong electron–phonon coupling at 0.65 THz (22 cm−1) probed by femtosecond terahertz emission51 and the light-induced I–Pb–I angle displacement measured by electron scattering52.

Figure 6 displays a schematic two-dimensional PES diagram for the polaron state formation. The PES for the neutral and polaron states have different potential minima which are Sneu(0, 0) and Spol(ΔStr, ΔBend), respectively. The geometry changes are determined predominantly by an I–Pb–I bending normal mode at 21 cm−1 (Fig. 3a) and an I–Pb–I c-axis stretching normal mode at 75 cm−1 (Fig. 3c). After excitation to the Franck–Condon state, SFC(0, 0), the displacements cause the excited-state nuclear wave packets to evolve along these multi-dimensional I–Pb–I vibration coordinates coherently propagating excited-state population toward the polaron state minima Spol(ΔStr, ΔBend) in the first few picoseconds. Thus, we suggest that coherent polaron formation dynamics is linked to the efficient charge-separation of MAPbI3 perovskite by directing the phase–space evolution to the polaron state faster than competing relaxation mechanisms. Other reports have suggested the subsequent dynamics of charge carriers as large polarons, where limited charge–carrier mobility was linked to coupling to LO phonon branches with frequency of 88 cm−1 53,54.

Excited-state potential energy surface diagram. The diagram displays the atomically displaced (∆Str, ∆Bend) polaron state surface relative to the ground state (0, 0) neutral surface after excitation. A coherent nuclear wave packet oscillates along the I–Pb–I stretching coordinate and propagates toward ∆Bend along the I–Pb–I bending coordinate. SFC, Sneu, and Spol are relative structures of Franck–Condon state, neutral, and polaron states

In summary, we performed femtosecond TA and DFT simulations to probe the excited-state dynamics of MAPbI3 and found evidence for coherent skeletal vibration dynamics that lead to formation of a polaron state underscoring charge separation. The low frequency wave packet modes are observed principally for the Pb–I bending and stretching vibrations resulting from the different geometry of the polaron state compared to the neutral state. We analyzed the experimental and theoretical displacements and confirmed that the theoretical negative polaron state structure is supported by the experimental Raman intensity analysis results. Thus, the distorted octahedral geometry of the PbI64−polaron state structure is characterized, and its initial formation dynamics are demonstrated to be dominated by the coherent nuclear wave packet motion. The high efficiency of MAPbI3 perovskite solar cells may be yet another example of the importance of vibrational coherence in efficient photochemical dynamics55,56,57.

Methods

Sample preparation

Samples were prepared by dissolving 0.76 mmol PbI2 (99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich) and 2.28 mmol CH3NH3I (Dyesol Inc.) in 1 mL anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF, Sigma-Aldrich), and stirred overnight. The prepared solution was spun on O2-plasma treated glass substrates at 1500 rpm for 60 s, and then annealed at 120 °C for 60 min in a N2-filled glovebox. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) was coated on the fresh MAPbI3 layer to protect it from the atmosphere. We have checked powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measured by using a Bruker AXS D8 Advance diffractometer with a Cu Kα source. (Supplementary Fig. 2)

Pump-probe spectroscopy

A home-built Kerr lens mode-locked Ti:sapphire oscillator (~20 fs FWHM, 5.3 nJ/pulse, 91 MHz) seeded a Ti:sapphire regenerative amplifier (B.M. Industries, Alpha 1000 US, 991 Hz, 70 fs, 780 μJ/pulse, λmax = 790 nm) pumped by a Q-switched Nd:YLF (B.M. Industries, 621-D). The fundamental at 790 nm was used to generate visible pump pule (~35 fs FWHM, 150 nJ/pulse, λmax=560 nm) by a non-collinear optical parametric amplifier (NOPA). A negatively chirped mirror pair (Layertec GmbH) was used to compress the pump pulse. A small portion of the fundamental is focused onto a 3 mm thick sapphire plate to generate a broadband continuum probe pulse (~10 fs FWHM, ~3 nJ/pulse). The probe pulse was temporally compressed in the 830–940 nm region with a pair of BK7 dispersion prisms (Supplementary Fig. 3). The cross-correlation function was measured to be a Gaussian function with ~44 fs FWHM by using the optical Kerr effect in cyclohexane (Supplementary Fig. 4). The power of the pump pulse was reduced to ~6 nJ to avoid thermal and photochemical damage to the sample. A custom-made N2 gas-flow chamber was used to prevent humidity-degradation of the MAPbI3 sample. A monochromator (Instruments SA, HR320), a laser-synchronized CCD (Princeton Instruments, PIXIS), and an optical chopper (Newport, 3501) were used to measure the optical density (OD) differences in every pump/probe cycle (Supplementary Fig. 3). Python and Matlab software were used to control the experimental instruments and analyze data, respectively.

Calculation of vibration frequencies

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using VASP58,59. Our VASP calculations use the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)59, and projected augmented-wave pseudopotentials60,61. Structural and electronic properties were computed using a plane-wave energy cut-off of 500 eV and a 4 × 4 × 4 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid62, including spin–orbit interactions (SOI). Lattice constants and internal atomic positions were relaxed starting from the experimental structure, without symmetry constrains, until forces were smaller than 1 meV/Å. Phonon eigenfrequencies and eigenvectors were calculated in the harmonic approximation, neglecting SOI. Our phonon calculations use density functional perturbation theory and a finer 6 × 6 × 6 k-point grid. Selected phonon modes and electronic orbitals were plotted using VESTA. The room temperature tetragonal (I4/mcm) phase of (CH3NH3)PbI3 is simulated in a \(\sqrt 2\) × \(\sqrt 2\) × \(2\) perovskite unit cell. The tetragonal structure consists of a PbI6 octahedral rotation around the z-axis (a0a0c− in Glazer notation) and an antiparallel orientation of the CH3NH3 (MA) molecules42,63,64.

Optimization of polaron structure

All calculations of HOIP isolated clusters were performed using the CAM-B3LYP functional combined with the LANL2dz (for Pb and I) and 6-31 G* (for N, C, and H) basis sets using Gaussian 09 software package65. In addition, we include a polar solvent (ε = 78) via the conductor-like polarizable continuum model66.

Several considerations were taken into account when designing the isolated HOIP structures. We started with the low temperature cubic lattice parameters that were derived from variable temperature powder x-ray diffraction experiments67. In order to minimize dangling bonds, the cluster was terminated on all sides with MAI. Equations 1 and 2 ensure that the system is overall neutral

Here \(n_{\rm Pb},\;n_{\rm {MA}},\;{\rm and}\;{\it n}_{\rm I}\) are the number of Pb, MA, and I atoms, respectively. I1 corresponds to an atom on the surface and is only bonded to one Pb atom, while I2 corresponds to an I atom that is bonded to two Pb atoms. The cluster needs to be large enough to include at least 8 MA cations surrounding the central Pb atom. To fulfill all conditions, we end up with a cluster having the following stoichiometry: MA54Pb27I108 (I1=I2=54). A cube fully terminated by MA and I would require 64 MA molecules. In order to realize charge balance between the ions and maximize symmetry, MA’s were removed from the 8 corners and on two opposite edges.

In addition, the polaron geometry in HSE hybrid potential was checked. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the optimized geometries from CAM-B3LYP (19 to 60% HF) and HSE (25 to 0% HF) functionals. The arrows point in the direction the atoms move in the formation of the polaron. This shows that the trend (I–Pb–I bending & c-axis elongation) still holds although the amplitude changes slightly.

Raman mode assignment

Since we measured the excited-state Raman signals originated from the structural displacements (Δ) between the ground and excited states in MAPbI3, we considered Rashba band splitting and polaron formation for the reason of the excited-state displacements. The former one is related to IR-active vibration modes, because the splitting is promoted with directional structural strains. Meanwhile the latter, the polaronic PbI64− is rather induced by symmetric structural changes from the neutral PbI64− of the ground state, because a negative charge (−1) is localized in 6p orbital of the center Pb. Thus, this polaronic structure shows the Pb-centered symmetric distortion shown in Fig. 4. Based on this idea, our Raman mode assignments have been done with the octahedral PbI64− Raman modes in the D4h Raman mode pool43. Thus, the Pb-centered Raman modes are easily discriminated from other IR-active and Pb-moving Raman modes (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 50). Prog. Photo.: Res. Appl. 25, 668–676 (2017).

Wang, H. & Kim, D. H. Perovskite-based photodetectors: materials and devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 5204–5236 (2017).

Shin, S. S. et al. Tailoring of electron-collecting oxide nanoparticulate layer for flexible perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1845–1851 (2016).

Seo, G. et al. Microscopic analysis of inherent void passivation in perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1705–1710 (2017).

Kim, Y. C. et al. Beneficial effects of PbI2 incorporated in organo-lead halide perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502104 (2016).

Lai, M. et al. Structural, optical, and electrical properties of phase-controlled cesium lead iodide nanowires. Nano Res 10, 1107–1114 (2017).

Tsai, H. et al. High-efficiency two-dimensional Ruddlesden–Popper perovskite solar cells. Nature 536, 312–316 (2016).

Pedesseau, L. et al. Advances and promises of layered halide hybrid perovskite semiconductors. ACS Nano 10, 9776–9786 (2016).

Buriak, J. M. et al. Virtual issue on metal-halide perovskite nanocrystals—a bright future for optoelectronics. Chem. Mater. 29, 8915–8917 (2017).

Xing, J. et al. High-efficiency light-emitting diodes of organometal halide perovskite amorphous nanoparticles. ACS Nano 10, 6623–6630 (2016).

Yang, S., Fu, W., Zhang, Z., Chen, H. & Li, C.-Z. Recent advances in perovskite solar cells: efficiency, stability and lead-free perovskite. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 11462–11482 (2017).

Yang, W. S. et al. Iodide management in formamidinium-lead-halide-based perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Science 356, 1376–1379 (2017).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 897–903 (2014).

Yang, W. S. et al. High-performance photovoltaic perovskite layers fabricated through intramolecular exchange. Science 348, 1234–1237 (2015).

Park, N.-G. Methodologies for high efficiency perovskite solar cells. Nano Converg. 3, 15 (2016).

Heo, S. et al. Deep level trapped defect analysis in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells by deep level transient spectroscopy. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1128–1133 (2017).

Gélvez-Rueda, M. C. et al. Effect of cation rotation on charge dynamics in hybrid lead halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 16577–16585 (2016).

Leblebici, S. Y. et al. Facet-dependent photovoltaic efficiency variations in single grains of hybrid halide perovskite. Nat. Energy 1, 16093 (2016).

Thu Ha, Do. T. et al. Optical study on intrinsic exciton states in high-quality CH3NH3PbBr3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075308 (2017).

Venkatesan, S. et al. Tailoring nucleation and grain growth by changing the precursor phase ratio for efficient organic lead halide perovskite optoelectronic devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 5, 10114–10121 (2017).

Jonathan, D. M. Grain boundaries in CdTe thin film solar cells: a review. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 31, 093001 (2016).

Rißland, S. & Breitenstein, O. Evaluation of recombination velocities of grain boundaries measured by high resolution lock-in thermography. Energy Procedia 38, 161–166 (2013).

Yang, J., Siempelkamp, B. D., Liu, D. & Kelly, T. L. Investigation of CH3NH3PbI3 degradation rates and mechanisms in controlled humidity environments using in situ techniques. ACS Nano 9, 1955–1963 (2015).

Zhu, X. Y. & Podzorov, V. Charge carriers in hybrid organic–inorganic lead halide perovskites might be protected as large polarons. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4758–4761 (2015).

Kang, B. & Biswas, K. Shallow trapping vs. deep polarons in a hybrid lead halide perovskite, CH3NH3PbI3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 27184–27190 (2017).

Stranks, S. D. et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science 342, 341–344 (2013).

Oga, H., Saeki, A., Ogomi, Y., Hayase, S. & Seki, S. Improved understanding of the electronic and energetic landscapes of perovskite solar cells: high local charge carrier mobility, reduced recombination, and extremely shallow traps. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13818–13825 (2014).

Wehrenfennig, C., Liu, M., Snaith, H. J., Johnston, M. B. & Herz, L. M. Charge-carrier dynamics in vapour-deposited films of the organolead halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3−xCl x . Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2269–2275 (2014).

Miyata, K. et al. Large polarons in lead halide perovskites. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701217 (2017).

Ivanovska, T. et al. Long-lived photoinduced polarons in organohalide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 3081–3086 (2017).

Welch, E., Scolfaro, L. & Zakhidov, A. Density functional theory+U modeling of polarons in organohalide lead perovskites. AIP Adv. 6, 125037 (2016).

Niesner, D. et al. Persistent energetic electrons in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15717–15726 (2016).

Zhu, H. M. et al. Screening in crystalline liquids protects energetic carriers in hybrid perovskites. Science 353, 1409–1413 (2016).

Neukirch, A. J. et al. Polaron stabilization by cooperative lattice distortion and cation rotations in hybrid perovskite materials. Nano. Lett. 16, 3809–3816 (2016).

Lee, G., Kim, J., Kim, S. Y., Kim, D. E. & Joo, T. Vibrational spectrum of an excited state and Huang–Rhys factors by coherent wave packets in time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. Chemphyschem 18, 670–676 (2017).

Hoffman, D. P. & Mathies, R. A. Femtosecond stimulated Raman exposes the role of vibrational coherence in condensed-phase photoreactivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 616–625 (2016).

Park, M., Im, D., Rhee, Y. H. & Joo, T. Coherent and homogeneous intramolecular charge-transfer dynamics of 1-tert-Butyl-6-cyano-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (NTC6), a rigid analogue of DMABN. J. Phys. Chem. A 118, 5125–5134 (2014).

Dietze, D. R. & Mathies, R. A. Femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. Chemphyschem 17, 1224–1251 (2016).

Wang, H., Valkunas, L., Cao, T., Whittaker-Brooks, L. & Fleming, G. R. Coulomb screening and coherent phonon in methylammonium lead iodide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 3284–3289 (2016).

Pollard, W. T., Lee, S. Y. & Mathies, R. A. Wave packet theory of dynamic absorption-spectra in femtosecond pump-probe experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 4012–4029 (1990).

Musser, A. J. et al. Evidence for conical intersection dynamics mediating ultrafast singlet exciton fission. Nat. Phys. 11, 352–357 (2015).

Park, M. et al. Critical role of methylammonium librational motion in methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) perovskite photochemistry. Nano. Lett. 17, 4151–4157 (2017).

Pérez-Osorio, M. A. et al. Vibrational properties of the organic–inorganic halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 from theory and experiment: factor group analysis, first-principles calculations, and low-temperature infrared spectra. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 25703–25718 (2015).

Hoffman, D. P., Ellis, S. R. & Mathies, R. A. Low frequency resonant impulsive Raman modes reveal inversion mechanism for azobenzene. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 11472–11478 (2013).

Gong, K., Kelley, D. F. & Kelley, A. M. Resonance Raman spectroscopy and electron–phonon coupling in zinc selenide quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 29533–29539 (2016).

Grenland, J. J., Lin, C., Gong, K., Kelley, D. F. & Kelley, A. M. Resonance Raman investigation of the interaction between aromatic dithiocarbamate ligands and CdSe quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 7056–7061 (2017).

Reimers, J. R. A practical method for the use of curvilinear coordinates in calculations of normal-mode-projected displacements and Duschinsky rotation matrices for large molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 115, 9103–9109 (2001).

Soufiani, A. M. et al. Impact of microstructure on the electron-hole interaction in lead halide perovskites. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1358–1366 (2017).

March, S. A. et al. Four-wave mixing in perovskite photovoltaic materials reveals long dephasing times and weaker many-body interactions than GaAs. ACS Photonics 4, 1515–1521 (2017).

Bakulin, A. A. et al. Real-time observation of organic cation reorientation in methylammonium lead iodide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 3663–3669 (2015).

Burak, G. et al. Terahertz emission from hybrid perovskites driven by ultrafast charge separation and strong electron–phonon coupling. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704737 (2018).

Wu, X. X. et al. Light-induced picosecond rotational disordering of the inorganic sublattice in hybrid perovskites. Sci. Adv. 3, 7 (2017).

Wright, A. D. et al. Electron–phonon coupling in hybrid lead halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 7, 11755 (2016).

Herz, L. M. Charge-carrier mobilities in metal halide perovskites: fundamental mechanisms and limits. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1539–1548 (2017).

Eames, C. et al. Ionic transport in hybrid lead iodide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7497 (2015).

Mathies, R. A. PHOTOCHEMISTRY: a coherent picture of vision. Nat. Chem. 7, 945–947 (2015).

Fang, C., Frontiera, R. R., Tran, R. & Mathies, R. A. Mapping GFP structure evolution during proton transfer with femtosecond Raman spectroscopy. Nature 462, 200–204 (2009).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab inito total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Kawamura, Y., Mashiyama, H. & Hasebe, K. Structural study on cubic-tetragonal transition of CH3NH3PbI3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 1694–1697 (2002).

Quarti, C., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Interplay of orientational order and electronic structure in methylammonium lead iodide: Implications for solar cell operation. Chem. Mater. 26, 6557–6569 (2014).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09 Revision B.01 (Gaussian Inc. Wallingford CT, 2009).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Baikie, T. et al. Synthesis and crystal chemistry of the hybrid perovskite (CH3NH3) PbI3 for solid-state sensitised solar cell applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 5628–5641 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The spectroscopic and theoretical works at University of California, Berkeley by M.P. was supported by the Mathies Royalty Fund. The work at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) by A.J.N and S.T. was supported by the LANL LDRD program and was done in part at Center for Nonlinear Studies (CNLS) and the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies CINT), a U.S. Department of Energy and Office of Basic Energy Sciences user facility, at LANL. This research used resources provided by the LANL Institutional Computing Program. LANL is operated by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396. S.E.R.-L. and J.B.N. acknowledge support from the Molecular Foundry (supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy), and the Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The material preparation work by M.L. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 within the Physical Chemistry of Inorganic Nanostructures Program (KC3103). M.L. thanks Suzhou Industrial Park for the fellowship support. S.E.R.-L. thanks Dirección General de Investigación at Universidad Andres Bello for support under Proyecto Interno Regular DI-21-18/“REG”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P. and R.A.M. conceived the project; M.P. collected and analyzed the TA data with the theoretical projection methods with contribution from S.R.E and D.D.; A.J.N undertook the polaron structure optimization with contributions from S.T.; S.E.R.-L. undertook the vibration frequency calculation with contribution from J.B.N.; M.L. prepared the sample and collected additional data with contribution from P.Y.; M.P., A.J.N., S.E.R.-L., S.T., and R.A.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions and advice from all others.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, M., Neukirch, A.J., Reyes-Lillo, S.E. et al. Excited-state vibrational dynamics toward the polaron in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. Nat Commun 9, 2525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04946-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04946-7

This article is cited by

-

Coupling to octahedral tilts in halide perovskite nanocrystals induces phonon-mediated attractive interactions between excitons

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Photocarrier-induced persistent structural polarization in soft-lattice lead halide perovskites

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Real-time observation of the buildup of polaron in α-FAPbI3

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Phonon-driven intra-exciton Rabi oscillations in CsPbBr3 halide perovskites

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Photoinduced large polaron transport and dynamics in organic–inorganic hybrid lead halide perovskite with terahertz probes

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.