Abstract

Study design:

A case report of a patient with spinal cord injury with autonomic dysreflexia and associated acute neurogenic pulmonary edema.

Objective:

To further describe autonomic dysreflexia as a potential cause of acute neurogenic pulmonary edema; specifically in a population with spinal cord injury.

Setting:

James A Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, FL, USA.

Methods:

A patient with a prior history of C5 AIS (ASIA impairment scale) B spinal cord injury was admitted for bowel preparation before a screening colonoscopy. During the 2-day bowel preparation, the patient developed severe autonomic dysreflexia. Due to persistent hypertension and acute onset respiratory failure, he required transfer to the intensive care setting.

Results:

Following a complicated course, the patient expired without a definitive cause of death. Autopsy findings showed gross and microscopic evidence of pulmonary edema.

Conclusions:

To date, the association between autonomic dysreflexia and acute neurogenic pulmonary edema is not described in the spinal cord or rehabilitation literature. The purpose of this case report is to further describe the overlooked and/or under reported incidence of acute neurogenic pulmonary edema associated with episodes of dysreflexia in a population with spinal cord injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

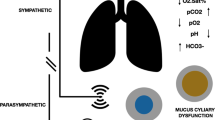

Initially described by Guttmann and Whitteridge in 1947,1 autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is an acute syndrome of excessive uncontrolled sympathetic signals. AD is a common complication found in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) with complete spinal lesions at or above the sixth thoracic (T6) neurologic level and the major splanchnic sympathetic outflow.2 As important, AD has been reported in patients with lesions below T6 and with incomplete injury.3

Clinically, the presentation of AD is associated with objective signs and subjective complaints including increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, bradycardia or tachycardia, pounding headache, cutis anserina, anxiety, flushing and sweating above the neurologic level of injury, malaise and nausea. Both noxious and non-noxious stimuli below the neurologic level of injury can result in a massive sympathetic response leading to vasoconstriction below the neurologic lesion. In patients with SCI, the descending central inhibitory pathways responsible for opposing the increased sympathetic response are disrupted; allowing unopposed peripheral and splanchnic vasoconstriction.2

Many of the complications typically associated with AD, such as headaches, seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage and atrial fibrillation, are well described in the literature.2 There is only brief mention of acute neurogenic pulmonary edema (NPE) in association with AD in the SCI and rehabilitation literature. To date, there is a single case report in the urology literature associating NPE with AD.4 This case report will present the complex management of AD and acute respiratory failure, as a result of NPE, in a patient with SCI.

Case report

A 50-year-old man with chronic C5 incomplete (ASIA impairment scale B) was admitted to the SCI ward for routine 2-day bowel preparation before a screening colonoscopy. The patient sustained his SCI as a result of a motor vehicle accident 22 years before and had no remote or current history of AD. Admission laboratory results—electrolytes, hemoglobin and white blood cell count—were unremarkable. The patient had no bowel movement at the first hospital day, and a bisacodyl suppository was added to the bowel regimen.

On the second hospital day, he had a large bowel movement and complained of abdominal cramping, headache and flushing. Hypertension (peak blood pressure: 210/110 mm Hg) and tachycardia (140 beats per min) were also documented. The patient had no prior history of AD associated with bowel movements. Abdominal discomfort and constipation were the only stimuli noted as a potential cause of AD (that is, no anal fissures, hemorrhoids or urinary obstruction was observed). This episode of AD was successfully managed within 30 min with topical and oral antihypertensive medications.

Approximately, 12 h after the first episode of AD, a second bowel movement was associated with complaints of headache, flushing and acute dyspnea. Blood pressure was 154/111 mm Hg, heart rate was 160 beats per min, and respiratory rate was 38 with a saturation of 73% on room air. Attempts were made to treat the patient's AD with oral and topical antihypertensive medication for 1 h without success. Subsequently, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for evaluation and management of acute respiratory failure and AD. Abdominal radiograph showed no evidence of obstruction/free air, chest radiographs showed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and no significant changes were noted on electrocardiogram testing. During intubation, the patient became asystolic requiring chest compressions, atropine and epinephrine. Following resuscitation, cardiology was consulted and a 2D echocardiogram was completed. Laboratory results following cardiac arrest are listed in Table 1. After neurologic consultation, the patient's family requested conservative management and the patient expired on hospital day 4.

Discussion

Neurogenic pulmonary edema is described as a common and under diagnosed entity, classically defined by the presentation of acute pulmonary edema secondary to a central neurologic insult. NPE is associated with head injury, seizures, intracranial hemorrhage and stroke among other injuries to the central nervous system.5 There are many proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms implicated in the presentation of NPE, including increased sympathetic activity resulting in constriction of the pulmonary veins leading to elevated pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure.6

Focusing upon the case presented here, the patient had no prior diagnosis of cardiac or pulmonary disease. The abnormal echocardiographic findings of an ejection fraction of 15%, akinetic anterior and anterolateral walls, and hypokinetic remaining walls were observed after the AD episode. Of note, a reduced ejection fraction and stunned myocardium have both been described in association with NPE.6 Postmortem examination of the heart showed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, no valvular disease, no significant coronary atherosclerosis, no atrial dilatation, no evidence of myocarditis and no evidence of myocardial infarct. The findings supporting the diagnosis of NPE include acute onset respiratory failure, bilateral pulmonary edema on chest radiography, reduced ejection fraction and stunned myocardium, no significant gross or microscopic postmortem cardiac pathology to indicate ischemia or myocarditis and increased lung weights and congestion (supporting a diagnosis of pulmonary edema).

The elevation in cardiac markers (Table 1) and white blood cell count noted after cardiopulmonary resuscitation complicates this case presentation. An elevation in white blood cell count has been described in association with administration of epinephrine and acute stress response. At the same time, all blood, lung and urine cultures were negative, further disproving infection. Studies have also shown elevations of cardiac markers in association with mechanical and chemical cardiopulmonary resuscitation.7 Without a prior history of ischemic heart disease or significant postmortem cardiac findings, it is possible that the elevation in cardiac markers was secondary to more global cardiac insult and not focal myocardial infarction. Although the elevated white blood cell count, left ventricular heart failure and elevated cardiac enzymes require a consideration of viral myocarditis as a potential cause of death, this diagnosis was ruled out postmortem. On the basis of the acute presentation of pulmonary edema without angina and the aforementioned clinical and postmortem findings, the authors attribute the patient's rapid decline to NPE.

The purpose of this case presentation is to further describe and emphasize the association between AD and NPE. The only reported case of AD as an etiology of NPE is in the urology literature.4 Further case presentations and studies are needed in the area of spinal cord medicine and rehabilitation to better understand the mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management of AD and NPE, as they relate to one another.

Conflicts of interest

No financial support was received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no commercial/conflict of interest to declare.

References

Silver JR . The history of Guttmann's and Whitteridge's discovery of autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 581–596.

Karlsson AK . Autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 383–391.

Moeller Jr BA, Scheinberg D . Autonomic dysreflexia in injuries below the sixth thoracic segment. JAMA 1973; 224: 1295.

Kiker JD, Woodside JR, Jelinek GE . Neurogenic pulmonary edema associated with autonomic dysrefelxia. J Urol 1982; 128: 1038–1039.

Ducker TB . Increased intracranial pressure and pulmonary edema. J Neurosurg 1968; 28: 112–123.

Baumann A, Audibert G, McDonnell J, Mertes PM . Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007; 51: 447–455.

Lin C, Chiu T, Fang J, Kuan J, Chen J . The influence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation without defibrillation on serum levels of cardiac enzymes: A time course study of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 2006; 68: 343–349.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calder, K., Estores, I. & Krassioukov, A. Autonomic dysreflexia and associated acute neurogenic pulmonary edema in a patient with spinal cord injury: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 47, 423–425 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.152

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.152

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Colorectal cancer screening in patients with spinal cord injury yields similar results to the general population with an effective bowel preparation: a retrospective chart audit

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Cardiovascular response during urodynamics in individuals with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2017)

-

Anästhesiologisches Vorgehen bei Patienten mit spinalem Querschnitt

Der Anaesthesist (2016)

-

Iatrogenic urological triggers of autonomic dysreflexia: a systematic review

Spinal Cord (2015)

-

Boosting in Elite Athletes with Spinal Cord Injury: A Critical Review of Physiology and Testing Procedures

Sports Medicine (2015)