Abstract

The bone-beds of the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group in Zhucheng, Shandong, China are rich in fossil remains of the gigantic hadrosaurid Shantungosaurus. Here we report a new oviraptorosaur, Anomalipes zhaoi gen. et sp. nov., based on a recently collected specimen comprising a partial left hindlimb from the Kugou Locality in Zhucheng. This specimen’s systematic position was assessed by three numerical cladistic analyses based on recently published theropod phylogenetic datasets, with the inclusion of several new characters. Anomalipes zhaoi differs from other known caenagnathids in having a unique combination of features: femoral head anteroposteriorly narrow and with significant posterior orientation; accessory trochanter low and confluent with lesser trochanter; lateral ridge present on femoral lateral surface; weak fourth trochanter present; metatarsal III with triangular proximal articular surface, prominent anterior flange near proximal end, highly asymmetrical hemicondyles, and longitudinal groove on distal articular surface; and ungual of pedal digit II with lateral collateral groove deeper and more dorsally located than medial groove. The holotype of Anomalipes zhaoi is smaller than is typical for Caenagnathidae but larger than is typical for the other major oviraptorosaurian subclade, Oviraptoridae. Size comparisons among oviraptorisaurians show that the Caenagnathidae vary much more widely in size than the Oviraptoridae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oviraptorosauria is a clade of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs characterized by a short, high skull, long neck and short tail. Derived oviraptorosaurs can be divided into two groups: the Caenagnathidae and the Oviraptoridae. Most known caenagnathid taxa, including Anzu wyliei1, Caenagnathus collinsi2, Chirostenotes pergracilis3, Apatoraptor pennatus4 and Microvenator celer5, were collected from North America. However, several caenagnathids have been found in Asia, including Caenagnathasia martinsoni6, Elmisaurus rarus7, and the enigmatic Gigantoraptor erlianensis1,8.

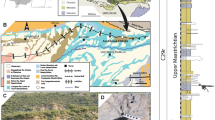

Over the last decade we have organized several major excavations in the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group at the Zangjiazhuang, Longgujian, and Kugou localities, Zhucheng, Shandong Province, China, which are in close geographic and stratigraphic proximity to each other, and produce similar dinosaur assemblages dominated by colossal hadrosaurid specimens. These excavations have yielded at least four new dinosaur taxa, including a tyrannosaurid, two leptoceratopsids, and a ceratopsid9,10,11,12,13. The tyrannosaurid, Zhuchengtyrannus magnus, represents the only documented theropod in the Zhucheng dinosaurian fauna, although some undiagnostic additional tyrannosaurid specimens were described previously under the invalid name Tyrannosaurus zhuchengensis14. Here we describe a new theropod specimen from the Kugou Locality (Fig. 1). The specimen comprises only a partial left hindlimb, but nevertheless displays a unique combination of morphological features suggesting the presence of a previously unknown caenagnathid oviraptorosaur in the Zhucheng dinosaurian fauna. This new discovery, along with previously reported fossil remains, provides strong evidence supporting a close biogeographical relationship between the Zhucheng dinosaurian fauna and contemporary North American ones.

The type locality for Anomalipes zhaoi ZCDM V0020. Upper: map showing Zhucheng, Shandong Province, China (scale bars are 1000 km for China and 250 km for Shandong Province; star represents Zhucheng). Lower left: bone-bed exposed at the Kugou Locality. Lower right: holotype exposed during excavation. The map was traced by Yilun Yu in Photoshop CS6 (www.adobe.com/photoshop), and modified from Hone et al.13.

Results

Systematic palaeontology

Theropoda Marsh 1881

Oviraptorosauria Barsbold 1976

Caenagnathidae Sternberg 1940

Anomalipes zhaoi gen.et sp. nov

Etymology

Generic name is a combination of the Latin “Anomalus” and “pes”, referring to the unusual shape of the foot. Specific name is in honour of Xijin Zhao, a Chinese palaeontologist who has made great contributions to research on Zhucheng dinosaur fossils.

Holotype

ZCDM V0020 (Zhucheng Dinosaur Museum, Zhucheng, Shandong, China), an incomplete left hindlimb, including the left femur missing the distal end, the left tibia missing the proximal end, the left fibula missing the distal and proximal ends, a complete metatarsal III and two pedal phalanges. Although these bones are disarticulated, they are inferred to be derived from a single theropod individual given that 1) they were preserved in a small area of less than 0.3 square metres within a Shantungosaurus bonebed; and 2) no other theropod skeletal elements are preserved nearby.

Locality and horizon

Kugou, Zhucheng City, Shandong Province, China. Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group.

Diagnosis

A new caenagnathid with the following unique combination of features: femoral head anteroposteriorly narrow and somewhat deflected posteriorly; accessory trochanter low; lateral ridge present on femoral lateral surface; weak fourth trochanter present; metatarsal III with triangular proximal articular surface, prominent anterior flange near proximal end, medial hemicondyle much narrower than lateral hemicondyle, and longitudinal groove on distal articular surface; and pedal phalanx II-3 with lateral collateral groove deeper and more dorsally located than medial groove.

Description and comparisons

The left femur is well preserved, lacking only its distal end. The preserved part of the shaft is 277 mm long. Comparisons with the distal portions of the femora of other oviraptorosaurs (e.g. Nomingia gobiensis)15, based on such features as the presence of an intercondylar groove on the posterior surface of the distal portion of the preserved femoral shaft, suggest that the original length of the femur must have been approximately 300 mm. The femoral shaft is straight in anterior view and only slightly bowed anteriorly in lateral view, as in other derived Oviraptorosauria1,8,16,17,18,19,20.

The femoral head is anteroposteriorly narrow, unlike its more robust counterparts in other oviraptorosaurs1,4,5,6,8,17,18,21,22. It projects dorsomedially, forming an angle of 100° with the long axis of the shaft in anterior view, and also is strongly posteriorly deflected as in Gigantoraptor erlianensis8. The shape and orientation of the femoral head are almost certainly morphologically genuine because the femur in general has undergone little deformation during fossilization, though the posterior surface of the middle portion of the shaft is crushed inward. A circular fovea seems to be present on the medial surface of the femoral head (Fig. 2d), but this might be a preservational artefact. There is a wide oblique ligament sulcus on the posterior surface of the femoral head. A wide concavity separates the femoral head from the trochanteric crest to define a distinct femoral neck, which is also slightly constricted in proximal view (Fig. 2e) as in Anzu wyliei1, Chirostenotes pergracilis3, Caenagnathasia martinsoni6, Nankangia jiangxiensis18, Caenagnathus collinsi2, Khaan mckennai17, Gigantoraptor erlianensis8, Ajancingenia yanshini19, Microvenator celer5, Nomingia gobiensis15 and Avimimus portentosus21. The ventral margin of the femoral neck is straight in anterior view as in Caenagnathasia martinsoni6, rather than curved as in Chirostenotes pergracilis3, Khaan mckennai17, Nankangia jiangxiensis18, Anzu wyliei1 and Caenagnathus collinsi2 (Fig. 2a). The greater trochanter is anteroposteriorly expanded and has fused at least partially with the lesser trochanter and posterior trochanter to form a trochanteric crest, which is anteroposteriorly much wider than the femoral head as in other oviraptorosaurs1,3,5,6,8,15,17,18,19,21. The trochanteric crest is thicker and higher anteriorly than posteriorly, as in Gigantoraptor erlianensis8. However, the trochanteric crest is lower than the femoral head, due to the dorsal inclination of the latter. The posterior trochanter is prominent as in Khaan mckennai17, Nankangia jiangxiensis18, Ajancingenia yanshini19 and Gigantoraptor erlianensis8, whereas this structure is more subtly developed in Anzu wyliei1 and Caenagnathasia martinsoni6. The lesser trochanter is probably fully continuous with the greater trochanter, but this needs further confirmation because the proximal end of the lesser trochanter is broken. Nevertheless, the lesser trochanter is unlikely to be a broad wing-like structure deeply separated from the greater trochanter as in most non-pennaraptoran theropods, except derived therizinosauroids22 and derived alvarezsauroids23, but is probably cylindrical in cross section as in other pennaraptorans.

Preserved left femur, tibia, and fibula of Anomalipes zhaoi ZCDM V0020. Left femur in anterior (a), posterior (b), lateral (c), medial (d) and proximal (e) views. Left tibia in anterior (f), posterior (g) and distal (j) views. Shading indicates the articular facet for the ascending process of the astragalus. Left fibula in lateral (h) and medial (i) views. Abbreviations: act, accessory trochanter; dg, distinct groove; fc, fibular crest; fh, femoral head; ft, fourth trochanter; gt, greater trochanter; if, iliofibularis tubercle; ig, intercondylar groove; lm, lateral malleolus; lr, lateral ridge; lt, lesser trochanter; mm, medial malleolus; pt, posterior trochanter; taf, triangular articular facet. Scale bar 1 cm.

An accessory trochanter is present at the base of the lesser trochanter, and extends distally to a level about one-fourth of the way to the distal end of the femur (Fig. 2a,c,d). A prominent accessory trochanter has also been reported in the basal oviraptorosaurs Caudipteryx zoui24 and Avimimus portentosus21, and in several caenagnathids including Microvenator celer5, Caenagnathus collinsi2, Anzu wyliei1 and Chirostenotes pergracilis3. Posterior to the accessory trochanter, on the lateral surface of the femur, is situated a thick lateral ridge that extends further distally than the accessory trochanter (Fig. 2c). Such a ridge is not known in other oviraptorosaurs1,2,5,6,8,15,17,18, but is present in troodontids25,26 and dromaeosaurids27,28,29. The proximal end of this lateral ridge forms a slight expansion, which might represent a weak trochanteric shelf (posterolateral trochanter of some authors). Unlike in most oviraptorosaurs, but as in Avimimus portentosus21 and Caenagnathasia martinsoni6, a fourth trochanter is present along the posteromedial margin of the femoral shaft. Although the distal end of the femur is broken away, the intercondylar groove is continuous with a depression on the distalmost preserved portion of the posterior surface, which is probably a part of the popliteal fossa.

The left tibia is 325 mm long as preserved, and only the proximal end is missing. Comparisons with the proximal portions of the tibiae of other oviraptorosaurians (e.g. Nomingia gobiensis)15, based on such features as the relative position of the fibular crest, suggest that the original length of the tibia was about 360 mm. Combined with the estimated femoral length of 300 mm given earlier, this measurement would suggest a tibial length to femoral length ratio of approximately 1.20, similar to the value for Chirostenotes pergracilis3 but lower than those for Anzu wyliei1, Microvenator celer5, Caudipteryx zoui24, and Nomingia gobiensis15. The tibial shaft is slightly curved in anterior view, being convex in the lateral direction. The shaft is much greater in mediolateral width than in anteroposterior thickness, and the proximal half of the shaft has a sub-semilunate cross section due to the convexity of the posterior surface and relative flatness of the anterior surface. A semi-circular cross section seems to characterize the oviraptorosaurian tibia (Gregory F. Funston, personal communications). A 47-mm-long, straight-edged fibular crest is located on the lateral surface of the shaft, and does not continue to the proximal end of the tibia (Fig. 2f,g). The fibular crest trends slightly anteriorly as it extends distally. The transverse width of the tibial distal end is greater than that of the midshaft part of the bone. Immediately proximal to the distal end, the anterior surface of the tibial shaft bears a distinct large, triangular articular facet to accommodate the ascending process of the astragalus. This facet is proximodistally tall, and shifted laterally from the midline of the anterior surface of the shaft (Fig. 2f). The lateral and medial malleoli extend distally to nearly the same level (Fig. 2f,g), and a similar condition is present in Anzu wyliei1, Chirostenotes pergracilis3, Caudipteryx zoui24 and the Oviraptoridae. The distal surface of the tibia is sub-rectangular (Fig. 2j).

The left fibula is missing the proximal articular surface and the distal portion, and has a preserved length of 170 mm. The proximal portion of the fibula is somewhat D-shaped in cross section, with a convex lateral surface and a flat medial surface. A prominent iliofibularis tubercle, which is about 20 mm long proximodistally, projects anterolaterally from the shaft (Fig. 2h,i). Distal to the iliofibularis tubercle, the fibular shaft gradually tapers. The medial surface of the distalmost portion of the fibular shaft bears a distinct groove.

The left metatarsal III is completely preserved (Fig. 3a–f), with a measured length of 167 mm. Based on the estimated femoral length of 300 mm, the ratio of the length of metatarsal III to that of the femur is 0.56, a value comparable to those for most caenagnathids but greater than those for most oviraptorids. The proximal end of metatarsal III is transversely strongly compressed, the ratio of maximum anteroposterior thickness to maximum transverse width being about 2.1. The compression is greatest at the anterior margin of the proximal end, so that the proximal articular surface of metatarsal III is triangular in outline (Fig. 3e). A transversely pinched proximal end of metatarsal III is also seen in other caenagnathids and in some basal oviraptorosaurs3,7,21,24, and in some cases (e.g. Chirostenotes pergracilis, Elmisaurus rarus and Avimimus portentosus) the compression is sufficiently extreme to produce an arctometatarsalian pes. However, the more distal portion of the shaft is transversely much wider than anteroposteriorly deep in some caenagnathids30,31, as in some theropods with a proximally pinched metatarsal III such as the troodontid Sinovenator (IVPP V12583). The compressed proximal portion of the anterior surface of metatarsal III forms a prominent flange (Fig. 3a,b,d). The proximalmost part of the medial surface of the shaft bears a triangular articular facet for metatarsal II. The shaft of metatarsal III is anteroposteriorly deeper than transversely wide, and has a sub-rectangular cross-section proximally and a triangular one more distally. Gigantoraptor erlianensis has a similar metatarsal III: the proximal end is about twice as anteroposteriorly deep as transversely wide; an anterior flange, albeit a proximodistally shorter one than in Anomalipes zhaoi, is present; and the shaft is sub-rectangular proximally (though slightly transversely wider than anteroposteriorly deep) and sub-triangular distally in cross section8. The posterior surface of the shaft bears a longitudinal ridge, whose proximal half is situated along the posteromedial edge of the shaft but whose distal half curves laterally as it extends distally. Near the distal end of the metatarsal, the ridge meets centrally along the shaft with the proximolaterally oriented medial hemicondyle (Fig. 3c). A second ridge, albeit an extremely weak one, runs along the posterolateral edge of the proximal part of the shaft but terminates about halfway along the shaft’s length. The distal articular surface of metatarsal III is slightly ginglymoid (Fig. 3c,d). The distal end of metatarsal III is more deeply grooved in Gigantoraptor erlianensis than in the present specimen8, but is non-ginglymoid in all other oviraptorosaurs. The anteroposterior thickness of the distal end is about 1.2 times the mediolateral width, and the anterior margin of the distal end is narrower than the posterior margin in distal view. The posterior hemicondyles of the distal end take the form of thick ridges and are both oriented obliquely, with the medial one extending proximolaterally and the lateral one proximomedially. The condyles converge on the central part of the shaft as they extend proximally, a feature also seen in some other caenagnathids30,31. The medial condyle is transversely wider and much more prominent in the posterior direction than the lateral condyle. A prominent, oblique, ridge-like medial hemicondyle is also seen at the distal end of metatarsal III in Gigantoraptor erlianensis8 and a similar, but much less strongly developed, medial hemicondyle is probably present in many other caenagnathids30,31. In Elmisaurus rarus7, Chirostenotes pergracilis3, Avimimus portentosus21 and Elmisaurus elegans16, the medial hemicondyle is slightly larger than the lateral one. Both medial and lateral collateral ligament fossae are present, and are large and deep (Fig. 3f).

Preserved pedal elements of Anomalipes zhaoi ZCDM V0020. Left metatarsal III in lateral (a), medial (b), posterior (c), anterior (d), proximal (e) and distal (f) views. Dark lines indicate ridges on the posterior surface of the shaft. Phalanx IV-1 in lateral (g), medial (h), proximal (i), and distal (j) views. Phalanx II-3 in lateral (k) and medial (l) views. Abbreviations: fl, flexor tubercle; lc, lateral condyle; lgf, ligament fossa; pdc, proximal dorsal crest; pdl, proximal dorsal lip; vr, ventral ridge; ptaf, proximal triangular articular facet; rlmh, ridge-like medial hemicondyle; vr, ventral ridge (extending to medial hemicondyle). Scale bar 1 cm.

Two left pedal phalanges are preserved, including one proximal phalanx and one ungual. The proximal phalanx, which probably represents pedal phalanx IV-1, is robust, the proximodistal length of the bone being only about 1.8 times the transverse width at the proximal end (Fig. 3g,h). The proximal articular surface is a deep concavity (Fig. 3i). In dorsal view, the mid-length portion of the shaft is mediolaterally constricted, and there is a moderately well developed extensor fossa close to the distal end. In medial view, the proximal half of the ventral surface of the phalanx can be seen to protrude ventrally as a prominent, block-like heel. The lateral surface of the shaft is convex along its length, and the medial surface is slightly concave. The distal end is strongly ginglymoid, with the medial hemicondyle larger than the lateral hemicondyle (Fig. 3j). The medial collateral ligament fossa is deeper than the lateral one (Fig. 3g,h).

The preserved ungual, possibly that of digit II, is robust and moderately recurved ventrally (Fig. 3k,l). When the ungual is held so that the proximal articular facet is vertical, the tip of the ungual is directed nearly ventrally. The proximal articular surface is sub-oval in outline, with a vertical ridge at the midline. Close to the proximal end is an extremely weak flexor tubercle, which is proximally bounded by ventral branches of the collateral groove on both the medial and the lateral sides. There is a proximodorsal lip, but the original size of this feature is uncertain due to breakage. The lateral surface of the ungual is more convex than the medial surface. Collateral grooves are present on both the medial and lateral surfaces of the ungual, and they each bifurcate proximally into a dorsal branch extending close to the proximodorsal corner of the ungual and a ventral branch extending to the ventral margin near the proximal end. The collateral grooves are proximally wide and shallow, but distally narrow and deep. The lateral collateral groove is deeper and more dorsally positioned than the medial groove, and its distal portion nearly contacts the ungual’s dorsal margin.

Methods

Phylogenetic analyses

In order to determine the systematic position of Anomalipes zhaoi, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of a matrix derived from a recently published comprehensive dataset for coelurosaurian theropod phylogeny32, but with the addition of Anomalipes zhaoi and 13 new characters (see Supplementary Information). The matrix was analysed using a “New technology search” in TNT version 1.1. Default settings were used for most parameters, but the value for “Find min. length” was changed from 1 to 10. The analysis produced 73 most parsimonious trees, each with a tree length of 3516, a CI of 0.311, and an RI of 0.775. Because the strict consensus of these 73 trees was poorly resolved in several areas, we calculated their reduced consensus following a previous study32. The reduced consensus is shown in Fig. 4a, and places Anomalipes zhaoi within the Oviraptorosauria.

Systematic position of Anomalipes zhaoi among the Coelurosauria. (a), Simplified reduced strict consensus of 73 most parsimonious trees resulting from phylogenetic analyses of dataset derived from Brusatte et al. (2014), with Anomalipes zhaoi and 13 new characters added in. (b), Simplified strict consensus of 3 most parsimonious trees resulting from phylogenetic analysis of dataset derived from Funston and Currie (2016), with 14 new characters and Anomalipes zhaoi added in.

We performed additional phylogenetic analyses in order to more precisely investigate the position of Anomalipes zhaoi within the Oviraptorosauria. The analyses were based on two recently published datasets for evaluating oviraptorosaurian phylogeny, respectively compiled by1 and Funston and Currie (2016), but the datasets were used with some modifications (see Supplementary Information). The two matrices (here termed the Lamanna Matrix and Funston and Currie Matrix, respectively) were analyzed in TNT version 1.1, using a traditional search (1000 replicates, 1000 random seeds, 10 trees saved per replication). Analysis of the Lamanna Matrix produced 860 most parsimonious trees, each with a tree length of 552, a CI of 0.524 and a RI of 0.687. Analysis of the Funston and Currie Matrix produced 3 most parsimonious trees, each with a tree length of 620, a CI of 0.497 and a RI of 0.675. Both analyses posited Anomalipes zhaoi as the sister taxon to Gigantoraptor erlianensis8 within the Caenagnathidae, and Fig. 4b shows the strict consensus of the most parsimonious trees produced by the analysis of the Funston and Currie Matrix (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

Anomalipes zhaoi is clearly a maniraptoran theropod, based on the presence of some distinctive maniraptoran hindlimb features. A distinct femoral neck, defined dorsally by an anteroposteriorly oriented concavity, separates the greater trochanter from the femoral head. This feature is seen in Oviraptorosauria, Therizinosauroidea33,34,35, Troodontidae36,37,38, and Alvarezsauroidea39,40. A similar groove is absent in basalmost theropods41, ceratosaurs42, basal tetanurans43,44,45, tyrannosauroids46,47,48,49, and ornithomimosaurs50,51,52. The greater trochanter is also expanded anteroposteriorly to the point of being considerably wider than the femoral head, as in Oviraptorosauria1,3,4,5,6,8,17,18,21,24,53, Troodontidae26,36,37,38, Dromaeosauridae27,28,54,55, and Therizinosauroidea33,34,35. In more basal theropods, the greater trochanter is anteroposteriorly narrower than the femoral head45,48,49,50. The distal end of the tibia has a sub-rectangular outline in distal view, resembling the equivalent structure in many other maniraptorans; in non-maniraptoran theropods such as ornithomimosaurs, tyrannosaurids, sinraptorids, carcharodontosaurids and abelisaurids, the distal articular surface is sub-triangular in distal view56.

In the context of Maniraptora, Anomalipes zhaoi displays several features suggesting pennaraptoran affinities. For example, the femoral lesser trochanter is finger-shaped and adheres to the greater trochanter. This stands in stark contrast to the condition in most non-pennaraptoran theropods, in which the lesser trochanter is separated from the greater trochanter by a deep cleft and is either alariform or spike-like. The only known non-pennaraptoran theropods with a finger-shaped lesser trochanter closely adhering to the greater trochanter are derived alvarezsauroids23,39, which are consistently much smaller than Anomalipes zhaoi, and derived therizinosauroids22, which dramatically differ from Anomalipes zhaoi in other hindlimb features.

Among the major pennaraptoran groups, Anomalipes zhaoi shows the clearest morphological resemblances to the Oviraptorosauria. For example, an elongate accessory trochanter is present, as in many basal oviraptorosaurs and caenagnathids. An accessory trochanter is not known in troodontids or in most dromaeosaurids, although this feature occurs in some small microraptorines. Anomalipes zhaoi has a small fourth trochanter as in the oviraptorosaurians Caenagnathasia martinsoni6 and Avimimus portentosus21. A fourth trochanter is absent in troodontids and many dromaeosaurids, though several dromaeosaurids such as Velociraptor mongoliensis do have an extremely small fourth trochanter28. A prominent mound-like trochanteric shelf is widely present in maniraptorans, including troodontids and dromaeosaurids, but is absent in Anomalipes zhaoi as in derived oviraptorosaurs.

The limited material, and particularly the lack of cranial material, in the holotype and only known specimen of Anomalipes zhaoi makes it difficult to identify striking caenagnathid features in this species. However, some recent studies provide significant new information on caenagnathid hindlimb morphology1,4,30,31, which can be used to confirm the caenagnathid affinities of Anomalipes zhaoi. In general, caenagnathids possess an elongated hindlimb with a particularly long tibia, a fused astragalocalcaneum, coossified distal tarsals and metatarsals, and an arctometatarsalian foot with a proximally strongly pinched metatarsal III1,31. In Anomalipes zhaoi the lower segments of the hindlimb appear relatively elongated (e.g. the tibia is about 1.2 and 2.1 times as long as the femur and metatarsal III, respectively, based on length estimates for the femur and tibia given above; the ratio of metatarsal III length to estimated femur length is 0.56), more closely resembling the condition in caenagnathids than that in oviraptorids. Anomalipes zhaoi lacks a typical arctometatarsalian foot, but its metatarsal III has a transversely strongly compressed proximal end, suggesting that the foot was incipiently arctometatarsalian. The compactness of the foot in Anomalipes zhaoi, which is typical of caenagnathids but not of oviraptorids, is further indicated by the relative slenderness of metatarsal III, which displays a ratio of length to midshaft transverse width of about 14.0. The Anomalipes zhaoi hindlimb lacks some fusion features normally seen in caenagnathids, but this is also true of a few previously described caenagnathids such as Gigantoraptor erlianensis. Furthermore, a prominent accessory trochanter and weak fourth trochanter are features widely present in basal oviraptorosaurians and caenagnathids, but not in oviraptorids. Most strikingly, Anomalipes zhaoi seems to possess cruciate ridges on the posterior surface of metatarsal III, a feature that has been recently identified to be unique to some caenagnathids30, in incipient form. In general, the hindlimb morphology of Anomalipes zhaoi is consistent with and suggestive of a phylogenetic position among basal caenagnathids.

The fact that phylogenetic analysis of both the Lamanna Matrix and the Funston and Currie Matrix recovered Anomalipes zhaoi and Gigantoraptor erlianensis as an endemic Asian oviraptorosaurian clade deserves special note. Despite their very different sizes, Anomalipes zhaoi and Gigantoraptor erlianensis share many similarities, including several that are unique among the Oviraptorosauria. These shared unique features include: femoral head with strong posterior deflection; trochanteric crest thicker and higher anteriorly than posteriorly; posterior trochanter prominent; and metatarsal III with anterior flange near proximal end, longitudinal groove on distal articular surface, and prominent oblique, ridge-like medial hemicondyle at distal end. To determine whether these hindlimb features imply any locomotor peculiarities would require a strict biomechanical analysis, but they nevertheless indicate the presence of an unusual endemic oviraptorosaurian group in the Late Cretaceous of Asia.

Size evolution has been explored previously in dinosaurs as a whole, and in dinosaurian sub-groups57,58,59,60,61,62. Some studies have revealed oviraptorosaurs and many other coelurosaurian clades, such as Tyrannosauroidea, Ornithomimosauria, Therizinosauroidea, Dromaeosauridae, and Troodontidae, to have been ancestrally relatively small in body size62,63,64. One study further explored size evolution in several herbivorous theropod sub-groups, including oviraptorosaurs, and found no evidence for directional size evolution in these groups57. Although we are not attempting to quantitatively assess trends in oviraptorosaur body size evolution in the present paper, the considerable size disparity existing within Oviraptorosauria8 prompted us to compile a dataset containing body mass estimates for as many oviraptorosaurian species as possible (see Supplementary Information), using an empirical equation based on femoral length65. Although this equation probably produces estimates that are less accurate than those generated by recently developed empirical equations relying on other parameters66, we nevertheless consider the equation we have chosen appropriate for our study given that length measurements are readily available and that our central objective is to reveal size differences among oviraptorosaurian taxa rather than necessarily to produce maximally precise absolute size estimates. Our body mass estimates for basal oviraptorosaurs range from 5–18 kg, whereas those for caenagnathids range from 3 to 3234 kg (most species >49 kg) and those for oviraptorids from 11 to 85 kg (most species >30 kg). Although these values are subject to uncertainty, they demonstrate clearly that in general basal oviraptorosaurs are relatively small and derived oviraptorosaurians relatively large, with typical caenagnathids larger than typical oviraptorids (Fig. 5). Furthermore, our data indicate much less size disparity within Oviraptoridae than within Caenagnathidae. For example, the largest known oviraptorid, Nankangia jiangxiensis18, is 85 kg in body mass, whereas the smallest, Khaan mckennai17, has a mass of 11 kg. For comparison, the largest known caenagnathid is Gigantoraptor erlianensis with a mass of 3234 kg, whereas the smallest is Microvenator celer5 with a mass of only 3 kg. The largest oviraptorid is thus about 8 times as large as the smallest, whereas for caenagnathids the largest exceeds the mass of the smallest by a factor of about 1078. These differences suggest a wider range of growth strategies and ecological niches in caenagnathids as opposed to oviraptorids, which should be considered further in future studies.

Simplified oviraptorosaurian phylogenetic tree, showing size ranges for basal oviraptorosaurs, the Caenagnathidae, and the Oviraptoridae. Grey boxes represent body mass ranges for three oviraptorosaurian groups: basal oviraptorosaurs, oviraptorids, and caenagnathids. See the electronic supplementary material for estimated body masses of various oviraptorosaurian species. Abbreviations: Caud: Caudipteryx zoui; Avim: Avimimus portentosus; Conc: Conchoraptor gracilis; Micr: Microvenator celer; Wula: Wulatelong gobiensis; Citi: Citipati osmolskae; Nank: Nankangia jiangxiensis; Anom: Anomalipes zhaoi; Neme: Nemegtia barsboldi; Anzu: Anzu wyliei; Giga: Gigantoraptor erlianensis.

References

Lamanna, M. C., Sues, H. D. & Schachner, E. R. A new large-bodied oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur from the latest Cretaceous of western North America. Plos One 10, e0125843 (2014).

Funston, G. F., Persons, I. W. S., Bradley, G. J. & Currie, P. J. New material of the large-bodied caenagnathid Caenagnathus collinsi from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Cretaceous Research 54, 179–187 (2015).

Currie, P. J. & Russell, D. A. Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 25, 972–986 (1998).

Funston, G. F. & Currie, P. J. A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36, e1160910 (2016).

Makovicky, P. J. & Sues, H.-D. Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of the theropod dinosaur Microvenator celer from the Lower Cretaceous of Montanta. American Museum Novitates 3240, 1–27 (1998).

Sues, H. D. & Averianov, A. New material of Caenagnathasia martinsoni (Dinosauria: Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan. Cretaceous Research 54, 50–59 (2015).

Osmólska, H. Coossified tarsometatarsi in theropod dinosaurs and their bearing on the problem of bird origins. Palaeontologia Polonica 42, 79–95 (1981).

Xu, X., Tan, Q.-W., Wang, J.-M., Zhao, X.-J. & Tan, L. A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the late Cretaceous of China. Nature 447, 844–847 (2007).

Xu, X., Wang, K., Zhao, X., Sullivan, C. & Chen, S. A New Leptoceratopsid (Ornithischia: Ceratopsia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Shandong, China and Its Implications for Neoceratopsian Evolution. Plos One 5, e13835 (2010).

Xu, X., Wang, K.-B., Zhao, X.-J. & Li, D.-J. First ceratopsid dinosaur from China and its biogeographical implications. Chinese Science Bulletin 55, 1631–1635 (2010).

He, Y. et al. A New Leptoceratopsid (Ornithischia, Ceratopsia) with a Unique Ischium from the Upper Cretaceous of Shandong Province, China. PLoS ONE 12, e0144148 (2015).

Zhao, X. J., Wang, K. B. & Li, D. J. Huaxiaosaurus aigahtens. Geological Bulletin of China 30, 1671–1688 (2011).

Hone, D. W. E. et al. A new, large tyrannosaurine theropod from the Upper Cretaceous of China. Cretaceous Research 32, 495–503 (2011).

Hu, C.-Z., Cheng, Z.-W., Pang, Q.-Q. & Fang, X.-S. Shantungosaurus giganteus. (Geological Publishing House, 2001).

Barsbold, R., Osmolska, H., Watabe, M., Currie, P. J. & Tsogtbaatar, K. A new oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Mongolia: the first dinosaur with a pygostyle. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 45, 97–106 (2000).

Currie, P. J. The first records of Elmisaurus (Saurischia, Theropoda) from North America. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 26, 1319–1324 (1988).

Balanoff, A. M. & Norell, M. A. Osteology of Khaan mckennai (Oviraptorosauria: Theropoda). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 372, 1–77 (2012).

Lü, J., Yi, L., Zhong, H. & Wei, X. A New Oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Southern China and Its Paleoecological Implications. Plos One 8, e80557 (2013).

Barsbold, R. Toothless carnivorous dinosaurs of Mongolia. Trudy Sovm Sov Mong Paleont Eksped 15, 28–39 (1981).

Xing, X. U. & Corwin, M. A. A new oviraptorid from the Upper Cretaceous of Nei Mongol, China, and its stratigraphic implications. Vertebrata Palasiatica 51, 85–101 (2013).

Kurzanov, C. M. Avimimids and the problem of the origin of birds. Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition Transactions 31, 1–92 (1978).

Clark, J. M., Maryanska, T. & Barsbold, R. In The dinosauria (second eidtion) (eds D. B., Weishampel, P., Dodson, & H., Osmolska) 151–164 (Univeristy of California Press, 2004).

Chiappe, L. M., Norell, M. A. & Clark, J. M. The Cretaceous, short-armed Alvarezsauridae: Mononykus and its kin. Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs, 87–120 (2002).

Zhou, Z. H., Wang, X. L., Zhang, F. C. & Xu, X. Important features of Caudipteryx—Evidence from two nearly complete new specimens. Vertebrata Pal Asiatica 38, 241–254 (2000).

Xu, X., Tan, Q.-W., Sullivan, C., Han, F. L. & Xiao, D. A short-armed troodontid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia and its implications for troodontid evolution. PLoS ONE 6, 1–12, e22916. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022916 (2011).

Zanno, L. E., Varricchio, D. J., O’Connor, P. M., Titus, A. L. & Knell, M. J. A new troodontid theropod, Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America. PLoS ONE 6, e24487, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024487 (2011).

Depalma, R. A., Burnham, D. A., Martin, L. D., Larson, P. L. & Bakker, R. T. The First Giant Raptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Hell Creek Formation (2015).

Norell, M. A. & Makovicky, P. J. Important features of the dromaeosaurid skeleton II: information from newly collected specimens of Velociraptor mongoliensis. American Museum Novitates 3282, 1–45 (1999).

Turner, A. H., Pol, D. & Norell, M. A. Anatomy of Mahakala omnogovae (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae), Tögrögiin Shiree, Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3722, 1–66 (2016).

Funston, G. F., Currie, P. J. & Burns, M. E. New elmisaurine specimens from North America and their relationship to the Mongolian Elmisaurus rarus. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 61, 159–173 (2016).

Currie, P. J., Funston, G. F. & OsmÓlska, H. New specimens of the crested theropod dinosaur Elmisaurus rarus from Mongolia. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 61, 143–157 (2016).

Brusatte, S. L., Lloyd, G. T., Wang, S. C. & Norell, M. A. Gradual assembly of avian body plan culminated in rapid rates of evolution across the dinosaur-bird transition. Current Biology 24, 2386–2392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.034. (2014).

Xu, X., Tang, Amp, Z. L. & Wang, X. L. A therizinosauroid dinosaur with integumentary structures from China. Nature 399, 350–354 (1999).

Xu, X. et al. A new therizinosauroid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol. Vertebrata Pal Asiatica 40, 228–240 (2002).

Zhang, X. et al. A long-necked therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol, People^s Republic of China. Vertebrata Pal Asiatica 39, 282–290 (2001).

Norell, M. A. et al. A review of the Mongolian Cretaceous dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda). American Museum Novitates 3654, 1–63 (2009).

Currie, P. & Peng, J. H. A juvenile specimen of Saurornithoides mongoliensis from the Upper Cretaceous of northern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 30, 2224–2230 (1993).

Xu, X. et al. The taxonomy of the troodontid IVPP V10597 reconsidered. Vertebrata Pal Asiatica 50, 140–150 (2012).

Perle, A., Chiappe, L. M., Barsbold, R., Clark, J. M. & Norell, M. A. Skeletal morphology of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda: Avialae) from the late Cretaceous of Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3105, 1–29 (1994).

Xu, X. et al. A basal parvicursorine (Theropoda: Alvarezsauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of China. Zootaxa 2413, 1–19 (2010).

Novas, F. E. New information on the systematics and postcranial skeleton of Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis (Theropoda: Herrerasauridae) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Upper Triassic) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13, 400–423 (1993).

Tykoski, R. S. & Rowe, T. In The Dinosauria (second edition) (eds D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, & H. Osmolska) 47–70 (University of Californai Press, 2004).

Canale, J. I., Novas, F. E. N. & Pol, D. Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas, de Valais, Vickers-Rich and Rich, 2005 (Theropoda: Carcharodontosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. Historical Biology 27, 1–32 (2015).

Holtz, T. R. J., Molnar, R. E. & Currie, P. J. In The Dinosauria (second edition) (eds D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, & H. Osmolska) 71–110 (University of California Press, 2004).

Madsen, J. H. Allosaurus fragilis: a revised osteology (1976).

Li, D., Norell, M. A., Gao, K. Q., Smith, N. D. & Makovicky, P. J. A longirostrine tyrannosauroid from the Early Cretaceous of China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 277, 183 (2010).

Brusatte, S. L., Benson, R. B. J. & Norell, M. A. The Anatomy of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and a Review of Its Tyrannosauroid Affinities. American Museum Novitates 8, 1–53 (2011).

Brusatte, S. L., Carr, T. D. & Norell, M. A. The Osteology of Alioramus, A Gracile and Long-Snouted Tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 366, 1–197 (2012).

Brochu, C. A. Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 7, 1–138 (2003).

Makovicky, P. J. et al. A giant ornithomimosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277, 191–198, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0236 (2009).

Smith, D., Galton, P., Smith, D. K. & Galton, P. M. Osteology of Archaeornithomimus asiaticus (Upper Cretaceous, Iren Dabasu Formation, People’s Republic of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 10, 255–265 (1990).

Makovicky, P. J., Kobayashi, Y. & Currie, P. J. In The Dinosauria (second edition) (eds D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, & H. Osmolska) 137–150 (University of California Press, 2004).

Osmólska, H., Currie, P. J. & Barsbold, R. In The Dinosauria 2nd edn (eds D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, & H. Osmólska) 165–183 (University of California Press, 2004).

Hwang, S. H., Norell, M. A., Ji, Q. & Gao, K. New specimens of Microraptor zhaoianus (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from northeastern China. American Museum Novitates 3381, 1–44 (2002).

Turner, A. H., Makovicky, P. J. & Norell, M. A. A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 371, 1–206 (2012).

Rauhut, O. W. M. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Palaeontology 69, 1–215 (2003).

Zanno, L. E. & Makovicky, P. J. No evidence for directional evolution of body mass in herbivorous theropod dinosaurs. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2526 (2013).

Hone, D. W., Keesey, T. M., Pisani, D. & Purvis, A. Macroevolutionary trends in the Dinosauria: Cope’s rule. J Evol Biol 18, 587–595, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00870.x (2005).

Benson, R. B. et al. Rates of dinosaur body mass evolution indicate 170 million years of sustained ecological innovation on the avian stem lineage. PLoS Biol 12, e1001853, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853 (2014).

Benson, R. B. J., Hunt, G., Carrano, M. T. & Campione, N. Cope’s rule and the adaptive landscape of dinosaur body size evolution. Palaeontology 61, 13–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12329 (2017).

Sookias, R. B., Butler, R. J. & Benson, R. B. J. Rise of dinosaurs reveals major body-size transitions driven by passive processes of trait evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 2180–2187, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.2441) (2012).

Lee, M. S. Y., Cau, A., Naish, D. & Dyke, G. Sustained miniaturization and anatomical innovation in the dinosaurian ancestors of birds. Science 345, 562–566 (2014).

Turner, A. H., Pol, D., Clarke, J. A., Erickson, G. M. & Norell, M. A. A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight. Science 317, 1378–1381 (2007).

Xu, X., Norell, M. A., Wang, X. L., Makovicky, P. J. & Wu, X. C. A basal troodontid from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 415, 780–784 (2002).

Christiansen, P. & Farin, R. A. Mass Prediction in Theropod Dinosaurs. Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology 16, 85–92 (2004).

Campione, N. E., Evans, D. C., Brown, C. M. & Carrano, M. T. Body mass estimation in non-avian bipeds using a theoretical conversion to quadrupedal stylopodial proportions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5, 913–923 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gregory F. Funston and an anonymous referee for their constructive comments, H.L. Zang for photography, Dr. S.L. Brusatte for discussion, and Drs. M.C. Lamanna and P.J. Currie for sharing data. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41688103, 91514302, 41120124002, and 41602013), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB18030504), the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No.173125), and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2017-06246) and start-up funding awarded by the University of Alberta to C.S.. Free online versions of TNT and Mesquite were provided by the Willi Hennig Society and the Free Software Foundation Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X., Y.L.Y. designed the project. All authors analysed the data. Y.L.Y., X.X. and C. S. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Wang, K., Chen, S. et al. A new caenagnathid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group of Shandong, China, with comments on size variation among oviraptorosaurs. Sci Rep 8, 5030 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23252-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23252-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.