Abstract

Natural soils are host to a high density1 and diversity2 of microorganisms, and even deep-earth porous rocks provide a habitat for active microbial communities3. In these environments, microbial transport by disordered flows is relevant for a broad range of natural and engineered processes, from biochemical cycling to remineralization and bioremediation4,5,6,7. Yet, how bacteria are transported and distributed in the subsurface as a result of the disordered flow and the associated chemical gradients characteristic of porous media has remained poorly understood, in part because studies have so far focused on steady, macroscale chemical gradients8,9,10. Here, we use a microfluidic model system that captures flow disorder and chemical gradients at the pore scale to quantify the transport and dispersion of the soil-dwelling bacterium Bacillus subtilis in porous media. We observe that chemotaxis strongly modulates the persistence of bacteria in low-flow regions of the pore space, resulting in a 100% increase in their dispersion coefficient. This effect stems directly from the strong pore-scale gradients created by flow disorder and demonstrates that the microscale interplay between bacterial behaviour and pore-scale disorder can impact the macroscale dynamics of biota in the subsurface.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Additional data that support the plots within this Paper and other findings of this study are available at the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3926720). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The algorithms and simulation codes are described in the Methods and Supplementary Information.

References

Whitman, W. B., Coleman, D. C. & Wiebe, W. J. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6578–6583 (1998).

Torsvik, V., Øvreås, L. & Thingstad, T. F. Prokaryotic diversity—magnitude, dynamics and controlling factors. Science 296, 1064–1066 (2002).

Chivian, D. et al. Environmental genomics reveals a single-species ecosystem deep within earth. Science 322, 275–278 (2008).

McClain, M. E. et al. Biogeochemical hot spots and hot moments at the interface of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Ecosystems 6, 301–312 (2003).

Tebo, B. M. et al. Biogenic manganese oxides: properties and mechanisms of formation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 32, 287–328 (2004).

Or, D., Smets, B. F., Wraith, J. M., Dechesne, A. & Friedman, S. P. Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media—a review. Adv. Water Resour. 30, 1505–1527 (2007).

Grathwohl, P. et al. Catchments as reactors: a comprehensive approach for water fluxes and solute turnover. Environ. Earth Sci. 69, 317–333 (2013).

Olson, M. S., Ford, R. M., Smith, J. A. & Fernandez, E. J. Quantification of bacterial chemotaxis in porous media using magnetic resonance imaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 3864–3870 (2004).

Wang, M. & Ford, R. M. Transverse bacterial migration induced by chemotaxis in a packed column with structured physical heterogeneity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 5921–5927 (2009).

Strobel, K. L. et al. Chemotaxis increases vertical migration and apparent transverse dispersion of bacteria in a bench-scale microcosm. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108, 2070–2077 (2011).

Blackburn, N., Fenchel, T. & Mitchell, J. Microscale nutrient patches in planktonic habitats shown by chemotactic bacteria. Science 282, 2254–2256 (1998).

Stocker, R. Marine microbes see a sea of gradients. Science 338, 628–633 (2012).

Szurmant, H. & Ordal, G. W. Diversity in chemotaxis mechanisms among the bacteria and archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 301–319 (2004).

Abraham, E. R. The generation of plankton patchiness by turbulent stirring. Nature 391, 577–580 (1998).

Tél, T., de Moura, A., Grebogi, C. & Károlyi, G. Chemical and biological activity in open flows: a dynamical system approach. Phys. Rep. 413, 91–196 (2005).

Taylor, J. R. & Stocker, R. Trade-offs of chemotactic foraging in turbulent water. Science 338, 675–679 (2012).

de Anna, P. et al. Mixing and reaction kinetics in porous media: an experimental pore scale quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 508–516 (2014).

de Anna, P., Quaife, B., Biros, G. & Juanes, R. Prediction of the low-velocity distribution from the pore structure in simple porous media. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 124103 (2017).

Long, T. & Ford, R. M. Enhanced transverse migration of bacteria by chemotaxis in a porous T-sensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 1546–1552 (2009).

Singh, R. & Olson, M. S. Transverse mixing enhancement due to bacterial random motility in porous microfluidic devices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 8780–8787 (2011).

Duffy, K. J., Ford, R. M. & Cummings, P. T. Residence time calculation for chemotactic bacteria within porous media. Biophys. J. 73, 2930–2936 (1997).

Ebrahimi, A. N. & Or, D. Microbial dispersal in unsaturated porous media: characteristics of motile bacterial cell motions in unsaturated angular pore networks. Water Resources Res. 50, 7406–7429 (2014).

Adadevoh, J. S., Triolo, S. C., Ramsburg, C. A. & Ford, R. M. Chemotaxis increases the residence time of bacteria in granular media containing distributed contaminant sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 181–187 (2016).

Adadevoh, J. S., Ostvar, S., Wood, B. & Ford, R. M. Modeling transport of chemotactic bacteria in granular media with distributed contaminant sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 14192–14198 (2017).

Wang, M., Lanning, L. & Ford, R. M. Enhanced retention of chemotactic bacteria in a pore network with residual NAPL contamination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 165–172 (2016).

Porter, M. L., Valdés-Parada, F. J. & Wood, B. D. Multiscale modeling of chemotaxis in homogeneous porous media. Water Resour. Res. 47, W06518 (2011).

Datta, S. S., Chiang, H., Ramakrishnan, T. S. & Weitz, D. A. Spatial fluctuations of fluid velocities in flow through a three-dimensional porous medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 064501 (2013).

Kang, P. K. et al. Pore-scale intermittent velocity structure underpinning anomalous transport through 3-D porous media. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6184–6190 (2014).

de Anna, P. et al. Flow intermittency, dispersion and correlated continuous time random walks in porous media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 184502 (2013).

Holzner, M., Morales, V. L., Willmann, M. & Dentz, M. Intermittent Lagrangian velocities and accelerations in three-dimensional porous medium flow. Phys. Rev. E 92, 013015 (2015).

Rusconi, R., Garren, M. & Stocker, R. Microfluidics expanding the frontiers of microbial ecology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 43, 65–91 (2014).

Hol, F. J. H. & Dekker, C. Zooming in to see the bigger picture: microfluidic and nanofabrication tools to study bacteria. Science 346, 1251821 (2014).

Bear, J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media (Elsevier, 1972).

Yawata, Y. et al. Competition–dispersal trade-off ecologically differentiates recently speciated marine bacterioplankton populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5622–5627 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Hydrodynamic effects on bacterial biofilm development in a microfluidic environment. Lab Chip 13, 1846–1849 (2013).

Taylor, G. I. Dispersion of soluble matter in solvent flowing slowly through a tube. Proc. R. S. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 219, 186–203 (1953).

Squires, T. M. & Quake, S. R. Microfluidics: fluid physics at the nanoliter scale. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 977–1026 (2005).

Sahimi, M. Flow phenomena in rocks: from continuum models to fractals, percolation, cellular automata and simulated annealing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 1393–1534 (1993).

Keller, E. F. & Segel, L. A. Model for chemotaxis. J. Theor. Biol. 30, 225–234 (1971).

Tuval, I. et al. Bacterial swimming and oxygen transport near contact lines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2277–2282 (2005).

Lazova, M. D., Ahmed, T., Bellomo, D., Stocker, R. & Shimizu, T. S. Response rescaling in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13870–13875 (2011).

Wang, M., Atencia, J. & Ford, R. M. Quantitative analysis of chemotaxis towards toluene by Pseudomonas putida in a convection-free microfluidic device. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 112, 896–904 (2015).

Crank, J. Mathematics of Diffusion 2nd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 1975).

Park, S. et al. Influence of topology on bacterial social interaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13910–13915 (2005).

Galajda, P. et al. Funnel ratchets in biology at low Reynolds number: choanotaxis. J. Mod. Opt. 55, 3412–3422 (2008).

Acknowledgements

P.d.A. acknowledges the Earth Resource Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the ERL fellowship that supported this research. R.J. acknowledges funding from the US Department of Energy (grant no. DE-SC0018357). R.S. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 315230_176189).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.d.A., R.S. and R.J. designed the research. P.d.A. and A.A.P. performed the research. Y.Y. contributed with chemotaxis steady experiments. P.d.A. and A.A.P. analysed data. P.d.A., A.A.P., Y.Y., R.S. and R.J. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Physics thanks Yohan Davit and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Schematic of the gradient generator used to assay chemotaxis in steady, linear chemoattractant profiles.

Schematic of the gradient generator used to assay chemotaxis in steady, linear chemoattractant profiles (adapted from ref. 34). a, Schematic of the cross-section of the assembled device (right) and top view of each layer (left). The top layer is made of PDMS, which is impermeable to solutes. The middle layer is made of agarose, which allows for the diffusion of chemoattractant used to establish the linear concentration profile. The bottom layer is a glass slide, used for structural support. Solid red arrows denote dimensions. b, Schematic of the gradient-generation mechanism. The continuous flow of chemoattractant (red) and filtered autoclaved seawater (blue) within the two irrigation channels in the PDMS layer mediates the formation of a horizontal gradient (red-blue shading) in the underlying agarose layer and therefore in the test channel.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial distribution of bacteria in the steady chemotaxis characterization experiment.

Spatial distribution of bacteria in the steady chemotaxis characterization experiment. The semi-logarithmic plot shows the average concentration of microbes along the negative-gradient direction. The linear trend indicates an exponential decay of the microbe concentration with distance from the attractant source and from the repellent sink (tryptone solution blue, spent medium red).

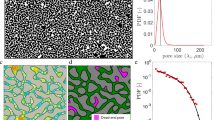

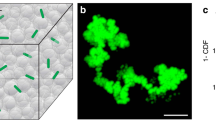

Extended Data Fig. 3 Large image of the microbes’ position at 6X magnification.

Large image of the microbes’ position at 6X magnification. The image is obtained as a composition of 2 × 6 individual pictures, using a phase contrast optical configuration. Individual microbes appear as white spots on a dark background, while larger circles and crescents are the vertical obstacles, mimicking the grains of a porous medium, which shape the flow heterogeneity in the microfluidics channel. Flow is from left to right.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measurement of the velocity field in the microfluidics flow cell.

Measurement of the velocity field in the microfluidics flow cell. a, Schematic of the spatial partition of the visible portion of the porous medium into tiles that are individually imaged and, then, analyzed with Particle Image Velocimetry. b, Fluorescent microspheres are suspended in the flow to seed the fluid and quantify its motion. c,d, Longitudinal and transverse velocity fields, respectively, in the same tile as (b).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Velocity field over the entire porous medium.

Velocity field over the entire porous medium. a,b, Longitudinal and transverse velocity fields, respectively, obtained by collecting the PIV results of each tile in which the whole medium has been partitioned. The color maps are set to obtain white color where the fluid velocity is zero, dark-red where the velocity is positive, and dark-blue where it is negative.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the signal detected from the emission of the invading fluorescent tracer at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the signal detected from the emission of the invading fluorescent tracer at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the concentration field that results from applying the calibration curve at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the concentration field that results from applying the calibration curve at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the rescaled concentration gradient field at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Results of the tracer transport/mixing experiment showing the rescaled concentration gradient field at three different times (t= 90 s, 185 s and 262 s).

Extended Data Fig. 9 The evolution of solute concentration field from the numerical model.

The evolution of solute concentration field from the numerical model for (a) the chemoattractant case, and (b) the chemorepellent case. In both cases, the concentration of solute in the medium is initially set at c(t=0) = 5 mg/mL. A higher concentration c = 50 mg/mL is injected in the chemoattractant case, whereas a lower concentration c = 0 mg/mL is injected in the chemorepellent case.

Extended Data Fig. 10 The evolution of normalized bacterial biomass in time.

The evolution of normalized bacterial biomass in time. Symbols represent the mean of the four experimental realizations, and solid lines represent the simulation results. The dashed lines represent the exponential fits to the experimental data at late times.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information, appendix, Figs. 1–23.

Supplementary Video 1

Raw video (12-bit greyscale) of a sharp front of PBS displacing a suspension of B. subtilis (bright), which are suspended in their spent medium. As the invading front advances, the microorganisms’ chemotactic response to the invading water front enhances their trapping in low-velocity zones.

Supplementary Video 2

Raw video (12-bit greyscale) of a sharp front of tryptone (solution of 50 mg ml−1 in PBS) displacing a suspension of B. subtilis (bright), which are suspended in their spent medium. As the invading front advances, the microorganisms’ chemotactic response to the invading tryptone front promotes their swimming away from the micropockets of accumulation, reducing their trapping.

Supplementary Video 3

Processed Video 1 with the suspension of B. subtilis shown in green.

Supplementary Video 4

Processed Video 2 with the suspension of B. subtilis shown in green.

Supplementary Video 5

The evolution of the spatial distribution of the displaced B. subtilis shown in Video 3 is here superposed on the velocity field \(| {\bf{u}}| =\sqrt{\{{u}_{x}^{2}+{u}_{y}^{2}\}}\) measured via PIV. Microorganisms tend to accumulate where the magnitude of the velocity field is very low (light colours), while they are transported away quickly in the channels of high velocity (darker colours).

Supplementary Video 6

The evolution of the spatial distribution of the displaced B. subtilis shown in Video 4 is here superposed on the velocity field \(| {\bf{u}}| =\sqrt{\{{u}_{x}^{2}+{u}_{y}^{2}\}}\) measured via PIV. Microorganisms that accumulate in stagnation zones (low magnitude of the velocity field, light colours) tend to swim out of these micropockets and get transported away quickly in the channels of high velocity (darker colours).

Supplementary Video 7

The evolution of the spatial distribution of the displaced B. subtilis shown in Video 3 is here superposed on the gradient residence time (Fig. 2a). In the presence of strong gradients of the invading solution, microorganisms tend to swim towards the stagnant zones where the concentration of their spent medium is still high.

Supplementary Video 8

The evolution of the spatial distribution of the displaced B. subtilis shown in Video 4 is here superposed on the gradient residence time (Fig. 2a). In the presence of strong gradients of the invading solution, microorganisms tend to swim away from the stagnant zones.

Supplementary Video 9

The evolution of the chemotactic Péclet number (Pec) from the numerical simulations, showing that regions of Pec > 1 (delineated by white contour line) persist in time much longer than the characteristic diffusion timescale τD ≈ 60 s.

Supplementary Video 10

The evolution of the bacterial concentration n from the numerical simulations for chemorepellent injection, illustrating enhanced trapping of bacteria in low-velocity micropockets.

Supplementary Video 11

The evolution of the bacterial concentration n from the numerical simulations for chemoattractant injection, illustrating enhanced removal of bacteria from low-velocity micropockets.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 3

Numeric data for Fig. 3; includes README file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Numeric data for Extended Data Fig. 2; includes README file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Numeric data for Extended Data Fig. 10; includes README file.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Anna, P., Pahlavan, A.A., Yawata, Y. et al. Chemotaxis under flow disorder shapes microbial dispersion in porous media. Nat. Phys. 17, 68–73 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-1002-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-1002-x

This article is cited by

-

Spatial structure, chemotaxis and quorum sensing shape bacterial biomass accumulation in complex porous media

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Self-transport of swimming bacteria is impaired by porous microstructure

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Flow Path Resistance in Heterogeneous Porous Media Recast into a Graph-Theory Problem

Transport in Porous Media (2023)

-

Dispersive transport dynamics in porous media emerge from local correlations

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Structure induced laminar vortices control anomalous dispersion in porous media

Nature Communications (2022)