Abstract

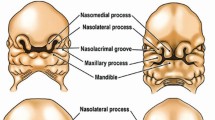

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) refer to clefts of the lip and palate, a heterogeneous group of relatively common congenital conditions that can cause mortality and significant disability if untreated, and residual morbidity even when treated with multidisciplinary care. Contemporary challenges in the field include: lack of awareness of OFCs in remote, rural and impoverished populations; uncertainties due to lack of surveillance and data gathering infrastructure; inequitable access to care in some parts of the world; and lack of political will combined with lack of capacity to prioritise research.

OFCs present clinically as either syndromic or non-syndromic, with the latter either being isolated or in conjunction with other malformations; however, many registries still do not differentiate between these fundamentally different entities and lump a spectrum of cleft types and sub-phenotypes together. This has implications for treatment, research and ultimately, quality improvement.

This paper deals with the challenges in contemporary management in terms of care and the prospects and possibilities for primary prevention of non-syndromic clefts. In terms of management and optimal care, there are also challenges in the provision of multi-disciplinary treatment and management of the consequences of being born with OFCs, such as dental caries, malocclusion and psychosocial adjustment.

Key points

-

Contemporary global challenges in the orofacial cleft field include lack of awareness, lack of data and inequitable access to comprehensive cleft care.

-

Failure to differentiate between orofacial cleft sub-phenotypes and to improve the standardisation of cleft classification has implications for treatment, research and quality improvement.

-

Prevention in the context of cleft care has a dual meaning. Primary prevention of non-syndromic clefts involves intensive research into the genetic and environmental factors implicated in the aetiology. Prevention is also applied to the management of the consequences of being born with a cleft, such as dental caries, malocclusion and psychosocial adjustment.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 24 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $10.79 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mossey P A, Little J. Epidemiology of oral clefts: an international perspective. In Wyszynski D F (ed) Cleft Lip and Palate: From Origin to Treatment. pp 127-158. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

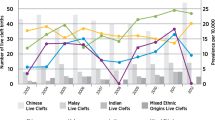

Kadir A, Mossey P A, Blencowe H et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Birth Prevalence of Orofacial Clefts in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2017; 54: 571-581.

World Health Organisation. Draft Global Oral Health Action Plan (2023-2030). 2023. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-global-oral-health-action-plan-(2023-2030) (accessed May 2023).

Rahimov F, Marazita M L, Visel A et al. Disruption of an AP-2alpha binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 1341-1347.

Houkes R, Smit J, Mossey P et al. Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2023; 60: 189-196.

Kriens O. What is a cleft lip and palate?: a multidisciplinary update: proceedings of an advanced workshop, Bremen 1987. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1989.

Zhang Z, Stein M, Mercer N, Malic C. Post-operative outcomes after cleft palate repair in syndromic and non-syndromic children: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2017; 6: 52.

McBride W A, Mossey P A, McIntyre G T. Reliability, completeness and accuracy of cleft subphenotyping as recorded on the CLEFTSiS (Cleft Service in Scotland) electronic patient record. Surgeon 2013; 11: 313-318.

Massennburg B B, Hopper R A, Crowe C S et al. Global Burden of Orofacial Clefts and the World Surgical Workforce. Plast Reconstr Surg 2021; 148: 568-580.

Frederick R, Hogan A C, Seabolt N, Stocks R M S. An Ideal Multidisciplinary Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Care Team. Oral Dis 2022; 28: 1412-1417.

Semb G, Enemark H, Friede H et al. A Scandcleft randomised trials of primary surgery for unilateral cleft lip and palate: 1. Planning and management. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2017; 51: 2-13.

Conroy E J, Cooper R, Shaw W C et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing palate surgery at 6 months versus 12 months of age (the TOPS trial): a statistical analysis plan. Trials 2021; 22: 5.

Sandy J, Williams A, Mildinhall S et al. The Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) Cleft Lip and Palate Study. Br J Orthod 1998; 25: 21-30.

Ness A, Wills A K, Waylen A et al. Centralization of cleft care in the UK. Part 6: a tale of two studies. Orthod Craniofac Res 2015; DOI: 10.1111/ocr.12111.

World Health Organisation. Global strategies to reduce the health-care burden of craniofacial anomalies: Report of WHO Meetings on International Collaborative Research on Craniofacial Anomalies. 2002. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42594 (accessed May 2023).

World Health Organisation. Global registry and database on craniofacial anomalies: Report of a WHO Registry Meeting on Craniofacial Anomalies. 2003. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42840 (accessed May 2023).

Allori A C, Kelley T, Meara J G et al. A Standard Set of Outcome Measures for the Comprehensive Appraisal of Cleft Care. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2017; 54: 540-554.

Galloway J, Davies G, Mossey P A. International Knowledge of Direct Costs of Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment. J Arch Paediatr Surg 2017; 1: 10-25.

Mossey P A, Clark J D, Gray D. Preliminary investigation of a modified Huddart/Bodenham scoring system for assessment of maxillary arch constriction in unilateral cleft lip and palate subjects. Eur J Orthod 2003; 25: 251-257.

Woodsend B, Koufoudaki E, Lin P et al. Development of intra-oral automated landmark recognition (ALR) for dental and occlusal outcome measurements. Eur J Orthod 2022; 44: 43-50.

Johnson C Y, Little J. Folate intake, markers of folate status and oral clefts: is the evidence converging? Int J Epidemiol 2008; 37: 1041-1058.

Little J, Cardy A, Munger R G. Tobacco smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2004; 82: 213-218.

Sabbagh H J, Hassan M H, Innes N P, Elkodary H M, Little J, Mossey P A. Passive Smoking in the Etiology of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Clefts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116963.

Mossey P A, Davies J A, Little J. Prevention of orofacial clefts: does pregnancy planning have a role? Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2007; 44: 244-250.

Cinar A B, Freeman R, Schou L. A new complementary approach for oral health and diabetes management: health coaching. Int Dent J 2018; 68: 54-64.

Sabbagh H J, Hassan M H, Innes N P, Baik A A, Mossey P A. Parental Consanguinity and Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefts in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2014; 51: 501-513.

Mangold E, Ludwig K U, Birnbaum S et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Nat Genet 2009; 42: 24-26.

Birnbaum S, Ludwig K U, Reutter H et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 473-477.

Ludwig K U, Mangold E, Herms S et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 968-971.

Leslie E J, Carlson J C, Shaffer J R et al. A multi-ethnic genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on 2p24.2, 17q23 and 19q31. Hum Mol Genet 2016; 25: 2862-2872.

Butali A, Mossey P A, Adeyemo W L et al. Genomic analyses in African populations identify novel risk loci for cleft palate. Hum Mol Genet 2019; 28: 1038-1051.

Awotoye W, Mossey P, Hetmanski J B et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals de-novo mutations associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 11743.

Grosen D, Chevrier C, Skytthe A et al. A cohort study of recurrence patterns among more than 54,000 relatives of oral cleft cases in Denmark: support for the multifactorial threshold model of inheritance. J Med Genet 2010; 47: 162-168.

Abirami S, Panchanadikar N, Muthu M S et al. Effect of Sustained Interventions from Infancy to Toddlerhood in Children with Cleft Lip and Palate for Preventing Early Childhood Caries. Caries Res 2021; 55: 554-562.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mossey, P. Global perspectives in orofacial cleft management and research. Br Dent J 234, 953–957 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5993-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5993-4

This article is cited by

-

COVID-19 vaccine and non-syndromic orofacial clefts in five arab countries. A case-control study

Clinical Oral Investigations (2024)

-

Knowledge assessment on cleft lip and palate among recently graduated dentists: a cross-sectional study

BMC Oral Health (2023)