Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy associated with dermatological manifestations are a well-recognized complication. These skin disorders can be associated with infiltration and proliferation of a malignant plasma cells or by a deposition of the monoclonal immunoglobulin in a nonmalignant monoclonal gammopathy. These disorders include POEMS syndrome, light chain amyloidosis, Schnitzler syndrome, scleromyxedema and TEMPI syndrome. This article provides a review of clinical manifestations, diagnostics criteria, natural evolution, pathogenesis, and treatment of these cutaneous manifestations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The monoclonal gammopathies are a spectrum of disorders characterized by clonal proliferation of plasma cells or lymphoid cells resulting in secretion of a monoclonal protein with clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to serious and even life-threatening disease. This secreted monoclonal protein (M-protein) is typically an intact immunoglobulin but can also be present as light chains unbound to any heavy chain (free light chain, FLC) and can be detected in the blood and/or urine [1].

The clone may remain indolent over a prolonged period, as in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). MGUS is asymptomatic and consistently precedes the development of smoldering myeloma and multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma represents the most common symptomatic and typically fatal part of the disease spectrum, with increasing tumor burden resulting in a multitude of clinical features like hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone disease (CRAB). However, the toxicity of secreted M-protein, alteration of the host immune system, secretion of cytokines, and plasma cell infiltration can produce severe manifestations even with a very small and quiescent clone. The kidney, peripheral nerves, and skin are the principal organs that can be involved [2]. Thus, monoclonal gammopathy associated with dermatological manifestations, grouped along with monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance (MGCS) is a well-recognized complication. According to Daoud & al., monoclonal gammopathy of skin significance can be divided into four different groups (Table 1) [3]. In Group I, infiltration, extension, and proliferation of malignant plasma cells are associated with cutaneous manifestations. In Group II, a nonmalignant monoclonal gammopathy is strongly associated with cutaneous disease. This can be caused by deposition of all or part of the monoclonal immunoglobulin, autoantibody activity, cytokine-mediated, and by an unknown mechanism. Group III are miscellaneous cutaneous manifestations anecdotally associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Small studies or case series should have clearly shown the correlation between Group III cutaneous manifestations and monoclonal gammopathy. Group IV are cutaneous conditions, symptoms, and complications related to M proteins, but not specific for monoclonal gammopathy. This may include adverse reactions to therapy used for the treatment of plasma cell disorders. Hyperviscosity-related gum bleeding in Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) and cutaneous infection associated with immunodeficiency are other examples of Group IV cutaneous conditions. Group III and IV cutaneous manifestations will not be discussed further in this review.

Investigation of unexplained cutaneous lesions should be carried out by a hematologist and dermatologist working together. Rheumatology, internal medicine, and ophthalmology consultation may also be relevant in certain situations. As described in the management algorithm (Fig. 1), every patient with a monoclonal gammopathy (or MGUS) with new unexplained cutaneous lesions should be investigated. In these cases, we recommend skin biopsy and bone marrow examination in addition of the standard laboratory evaluation of plasma cell dyscrasia. Additionally, patients with chronic unexplained cutaneous lesions associated with a monoclonal gammopathy should be investigated. In patients with plasma cell malignancies, investigations should be considered if cutaneous lesions are persistent despite treatment of the underlying condition. Finally, in patients with worsening or recalcitrant skin eruptions (particularly in the Group II category) that do not respond to skin-directed therapy, treatment of the underlying monoclonal gammopathy/malignancy could be considered as a primary treatment for the skin condition (since the skin condition may be “reactive” to the underlying monoclonal gammopathy). In this article, we summarize the clinical manifestations, diagnosis criteria, histopathological finding, and management of these uncommon cutaneous manifestations.

Group I

POEMS

POEMS syndrome is a rare monoclonal plasma cell disorder and refers to polyradiculoneuropathy (P), organomegaly (O), endocrinopathy (E), monoclonal gammopathy (M), and skin changes (S). Additional features include sclerotic bone lesions, Castleman disease, papilledema, pleural effusion, ascites, erythrocytosis, and thrombocytosis [4]. The diagnostic criteria for POEMS are shown in Table 2. The heavy chains in POEMS syndrome can be IgA, IgG, or more rarely IgM. However, the light chain is almost always lambda [5]. In patients without serum or urine M-protein (less than 12% of cases), a monoclonal lambda plasma cell is usually found [6]. There is a Castleman variant POEMS syndrome that does not have a monoclonal gammopathy [4].

The skin lesions associated with POEMS syndrome include hyperpigmentation, acrocyanosis, plethora, telangiectasia, hypertrichosis, and skin thickening [7]. Glomeruloid hemangioma, red-purple lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities are also present in many patients [8]. Patients can exhibit Raynaud phenomenon, flushing, and white nails. Sclerodermoid change characterized by skin thickening, facial lipoatrophy [9], and calciphylaxis may also occur [7, 10, 11].

Some studies have suggested a causative relationship between VEGF and skin lesions. Pihan & al. clearly demonstrated that raised VEGF seems to correlate with a high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome [12]. Indeed, elevated VEGF may lead to hypertrichosis by stimulating local vascularization and hyperpigmentation by increasing melasma lesions [13, 14]. Stromal and vascular change present in digital clubbing may be explained by VEGF when released with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) on platelet aggregation [15]. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR-1) by VEGF seems to play a central role in the development of hemangiomas [16].

In patients with 1 or 2 bone lesions and no bone marrow involvement, radiation therapy is the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy in limited disease can be curative and even improve cutaneous lesions [17]. If there are more than 2 bone lesions and/or a clonal plasma cell on bone marrow biopsy, systemic therapy can be considered despite no randomized trial available. Lenalidomide-based therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation is associated with a favorable prognosis [18,19,20].

Waldenström macroglobulinemia cutis

WM is defined as a clonal proliferation of lymphoplasmatic cells producing a monoclonal IgM protein. WM can be associated with small, pearly flesh-colored papules on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. These lesions are asymptomatic and may appear before or at the diagnosis of the WM. On histopathology, there are IgM deposits in the dermis without associated amyloid or cellular infiltration. Specimens are periodic acid-Schiff positive and show hyaline amorphous and granular eosinophilic deposits involving the upper and mid dermis [21].

Several cases of WM with bullous involvement have been reported [22, 23]. The typical clinical manifestations are blisters, erosions, or papules on the dorsum of the hands. The location of the vesicles was generally subepidermal with dermal deposits of IgM [24]. Some authors hypothesized that the pathogenesis can be similar to epidermolysis bullosa acquisita or bullous systemic lupus erythematous [25]. In a case report, a patient with hyperkeratotic colored papules achieved complete response with rituximab while the second rapidly progressed and died of disease progression [26]. Another patient with subepidermal bullae was successfully treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone [27].

Light chain amyloidosis (AL)

Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL) is due to an aberrant production of monoclonal kappa or lambda light chain that forms the substrate for amyloid fibril formation, and its deposition in different organs leading to organ damage and consequent clinical manifestations [28].

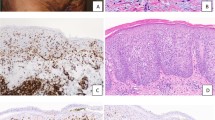

The dermatological manifestations in AL can be myriad (Fig. 2). Periorbital and facial purpura are classical signs of AL amyloidosis [29]. Petechia, scattered non-traumatic ecchymoses, nodules, alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes of the skin are seen. Papules with dome-shaped, waxy, translucent appearances are common. Oral involvement includes macroglossia, induration of the tongue, and gum bleeding. A case of uvula AL amyloidosis has also been reported [30]. Purpura may be the result of amyloid infiltration of blood vessels, acquired factor X deficiency, and increased fibrinolysis [31,32,33].

Nail dystrophy characterized by onychorrhexis, onychoschizia, and nail splitting has been reported. The distal nail plate involvement is generally more important than the proximal nail. Nail dystrophy may be misdiagnosed as trachyonychia and a careful evaluation of nail lesions must be done [34].

The diagnosis of amyloidosis is based on histopathological examination of tissues. Electron microscopy or Congo red may confirm the presence of amyloid deposits [35]. Skin biopsy usually demonstrates faintly eosinophilic amorphous masses of amyloid deposits in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues [3]. Mass spectrometry is the gold standard to confirm the amyloid protein composition and to distinguish AL amyloidosis from other forms [36,37,38].

In low-risk patients, autologous stem cell transplantation with high-dose melphalan is recommended with or without bortezomib or daratumumab-based induction [39,40,41,42]. Bortezomib consolidation should also be considered [43]. In intermediate-risk and high-risk patients, daratumumab in combination with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DARA-CyBorD) should be the first option [44, 45].

Cryoglobulinemia

Cryoglobulinemia is a disorder characterized by the presence of cryoglobulins which precipitate at temperatures below 37 degrees Celsius. Cryoglobulinemia has been classified into three different types. The type 1 cryoglobulinemia occurs in monoclonal gammopathies including MGUS, multiple myeloma, WM and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [46, 47].

In type II cryoglobulinemia, the cryoglobulins are a mixture of monoclonal immunoglobulin (typically IgM or otherwise IgG or IgA) in combination with rheumatoid factor (RF) and polyclonal IgG. Type II cryoglobulins are associated with hepatitis C infection, systemic lupus erythematous, Sjogren’s syndrome, or less frequently infection (hepatitis B virus or HIV) [48, 49]. Type III cryoglobulins have exclusively polyclonal IgG and polyclonal IgM with RF activities. They are associated with autoimmune disease and infections, mainly hepatitis C virus [50].

Cohen et al. published a description of cutaneous lesions found in 72 patients with cryoglobulinemia. Many patients had inflammatory macules or papules, hemorrhagic crusts, scarring, acrocyanosis, and livedo reticularis (Fig. 3). Hyperpigmentation of the leg after repeated episodes of purpura is frequent [51]. Ulcers and infarctions were also much more frequent in type I cryoglobulinemia than in type II and III [52]. Monoclonal cryoglobulins with high thermal insolubility may cause more severe ulceration [53]. The histopathological finding includes erythrocyte extravasation, hyaline thrombosis, non-inflammatory sequelae, and rarely vasculitis features. Type I cryoglobulinemia classically presents with non-inflammatory retiform (net-like) purpura with microscopic changes of microvascular occlusion; while types II and III cryoglobulinemia typically present with palpable purpura and microscopic changes of leukocytoclastic vasculitis [54]. The treatment should be directed against the underlying plasma cell disorder. In patients with acute kidney injury, bortezomib is the first choice of treatment for type 1 cryoglobulinemia, while in patients with neuropathy lenalidomide may be considered. If there is hyperviscosity, rituximab introduction should be delayed and plasmapheresis should be used [55]. In mixed cryoglobulinemia, treatment should include antiviral therapy with or without rituximab and corticosteroids according to the severity of the disease [56, 57].

Plasmacytoma

Plasmacytoma is defined as a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells and can involve skin. Skin plasmacytoma may be characterized by one or more skin lesions and can be associated with monoclonal gammopathy. This can take three different forms: (1) in association with multiple myeloma, (2) without association with multiple myeloma, and (3) direct extension from an underlying bone lesion. WM, heavy-light chain disease can develop skin plasmacytoma [58, 59]. IgD multiple myeloma would also present an increased risk for skin plasmacytoma in comparison with other isotypes [60].

Patients with skin plasmacytoma usually present with red, violaceous, non-tender nodules and occasionally with diffuse erythematous rash (Fig. 4). An erythematous patch overlying a solitary bone plasmacytoma and associated with local adenopathy (AESOP syndrome) has also been described [61]. Histopathological studies demonstrate clonal infiltration by plasma cells [51, 62, 63]. Current treatment options include localized radiation therapy, local surgery, and systemic treatment according to the number of tumors and their characteristics [64], but typically would require systemic therapy when part of myeloma.

Group II

Schnitzler syndrome

Schnitzler syndrome is a chronic urticaria associated with monoclonal gammopathy. This late onset acquired autoinflammatory disease was described by Liliane Schnitzler in 1972 [65]. Typically, an IgM gammopathy is found (mainly kappa). However, some cases of IgG are also reported (variant Schnitzler syndrome). The pathogenesis of Schnitzler syndrome is poorly understood and the role of the paraprotein is unclear. NLRP3-related autoinflammatory disease (NLRP3-AID), previously called Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are due to a gain-of-function mutation in NLRP3. Patients with NLRP3 presented similar clinical manifestations to patients with Schnitzler syndrome and both conditions show good response to IL-1 inhibition [66]. However, no study has reported a NLRP3 mutation in patients with Schnitzler syndrome [67, 68]. This mutation, therefore, does not seem to play a role in Schnitzler pathogenesis. Other studies found an increase of IL-1 beta and IL-6 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells [69, 70]. However, the mechanism of these chemokine upregulations remains unclear. High CCL2 levels have been found in Schnitzler patients and may be important in the pathogenesis of the disease [71]. More studies are needed to elucidate the pathogenesis of Schnitzler syndrome.

The urticarial rash (which may be non-pruritic) is described by rose or red macules or gently raised papules. The rash can be associated with dermographism and is mostly present on the trunk and extremities. Skin biopsy demonstrates neutrophilic perivascular and interstitial inflammation. Fibrinoid necrosis of vessels, endothelial swelling, and dermal hemorrhage are generally not present [72]. The term “neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis” has been used to describe the characteristic cutaneous clinical and histopathologic findings of Schnitzler syndrome, although similar findings can be seen in other systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, adult-onset Still disease, and periodic fever syndromes [72, 73] Many patients present with joint pain, bone pain, myalgia, and asthenia. The Strasbourg criteria must be fulfilled to confirm the diagnosis (Table 3) [74].

The treatment of choice for Schnitzler syndrome is IL-1 inhibition with anakinra, canakinumab, or rilonacept. Several studies show that anakinra relieves symptoms in only a few hours after administration [75,76,77,78]. A phase II randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that canakinumab, an IL-1 beta monoclonal antibody, significantly reduced clinical manifestations and inflammatory markers [79]. Rilonacept, in a prospective trial, was also effective to induce a rapid clinical response and reduced inflammation [80]. However, IL-1 inhibition does not reduce M-protein and has no impact on the natural history of the disease.

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is a non-Langerhans histiocytosis characterized by firm yellow or red-orange papules, plaques, and nodules. NXG is strongly associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of type IgG-kappa [81]. No M-proteins are found in 9–19% of cases with NXG. Some cases of IgA or IgG-lambda have been reported [82, 83]. Periorbital skin lesions are the most common site of involvement, but it can occur on the trunk and extremities in the absence of facial lesions [84]. Ocular changes include proptosis, blepharoptosis, scleritis, enlargement of lacrimal glands, and restricted ocular mobility [85]. Atrophy, telangiectasia, ulceration, and violaceous borders are reported. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and leukopenia are common findings. Histopathological findings include granulomatous inflammation in the dermis extending into subcutaneous fat. The granulomas are alternating with foci of collagen necrobiosis and are associated with epithelioid and foamy histiocytes in addition to lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells, also called Touton cells [86].

NXG is a chronic disease characterized by the progression of existing lesions if not treated. There is no existing randomized clinical trial considering its low prevalence. Alkylating agents chlorambucil and melphalan are the first line agents and retrospective studies have suggested their efficacy with or without corticosteroids [86,87,88]. High-dose dexamethasone and intravenous immunoglobulin can also be beneficial for NXG [89,90,91,92,93]. Lenalidomide, dapsone, and plasmapheresis are reserved for refractory cases [94,95,96].

Plane xanthoma

Diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma associated with monoclonal gammopathy is characterized by xanthelasma (periorbital plane xanthoma) and diffuse plane xanthoma of the head, neck, trunk, shoulders, or extremities. Xanthomas normally occur in hyperlipidemic patients, however, in rare cases it can occur in patients with normal lipid profiles. Normolipemic plane xanthoma can be associated with MGUS, multiple myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia, lymphoma, and Castleman disease. The skin lesions are described as yellowish-orange plaques [97]. The pathogenesis is unknown, but immune complex formation between antibodies and lipoproteins seems to cause accumulation of lipids in macrophages [98]. Plane xanthoma should be differentiated from necrobiotic xanthogranuloma by their diffuse and plane patches. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma are more polymorphic and tend to be described as red-brown, violaceous, or yellowish cutaneous plaques, papules, or nodules [99]. In patients with limited lesions, surgical resection or ablative laser therapy can be done [97, 100]. Otherwise, systemic treatment with bortezomib, melphalan, and/or high-dose corticosteroids can be done to achieve hematologic and cutaneous remission [98, 99].

Scleromyxedema

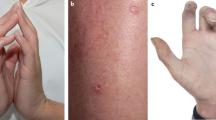

Scleromyxedema, a primary dermal diffuse mucinosis, was first described by Dubruilh and Reitmann as a skin disease similar to scleroderma [101, 102]. Mucinoses are characterized by mucin deposits in connective tissue. The skin demonstrates dense, firm, waxy, reddish or skin-colored, dome-shaped or flat-topped papules of 2–3 mm in size. It typically involves the hands, head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figs. 5 and 6). Scleromyxedema can lead to longitudinal furrows in the glabella, also called facies leonina. Deep furrowing on the trunk or limbs associated with redundant skin folds is also observed (Shar-Pei sign). Few patients also present with a central depression with a raised margin over the proximal interphalangeal joints (donut sign), sclerodactyly and Raynaud syndrome. Typically, patients do not have telangiectasia and cutaneous calcinosis in contrast with systemic sclerosis. Major complications of scleromyxedema are contractures of joints and articulations [103].

A monoclonal spike is found in 90% of patients with scleromyxedema, usually IgG lambda. However, IgA kappa, IgA lambda, and IgM kappa monoclonal spikes can also be found. Many neurological complications may arise with scleromyxedema: carpal tunnel syndrome, peripheral sensory and/or motor neuropathy, gait disorder, stroke, seizures, psychosis, and dermato-neuro syndrome [104]. The dermato-neuro syndrome is a flu-like prodrome followed by seizures and coma [105]. Other complications include dysphagia, scleroderma renal crisis-like, arthralgia, inflammatory myopathy, and severe destructive polyarthritis [106, 107]. Cardiovascular manifestations including heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, myocardial ischemia and pericardial may occur [108]. The pathogenesis of cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations is unknown. Many authors hypothesize that M-protein may stimulates the proliferation of fibroblasts and increase mucin formation [103, 109]. However, there is no correlation between M-protein levels and clinical manifestations.

Diagnostic criteria that should be fulfilled to confirm scleromyxedema [110]:

-

1.

Generalized papular and sclerodermiform eruption

-

2.

Mucin deposits, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis on histopathology

-

3.

Monoclonal gammopathy

-

4.

Absence of thyroid disease

Without adequate treatment, scleromyxedema tends to progress, may result in death, and spontaneous regression is exceptional [111]. Two prospective non-randomized trials showed that intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) 2 grams/kilogram each month are associated with significant clinical improvement [112, 113]. In a systemic review, Haber & al. showed cutaneous improvement in 69% of patients (n = 47) with immunoglobulin as single therapy. In addition, systemic corticosteroids, thalidomide, and autologous stem cell transplantation were respectively associated with 73, 69, and 100% improvements of cutaneous manifestations of scleromyxedema [114]. In context of dermato-neuro syndrome, the combination of IVIg and systemic corticosteroids are the treatment of choice according to European guidelines [115]. Lenalidomide [116] or bortezomib therapy [117,118,119] may achieve rapid improvement of cutaneous and systemic manifestations of scleromyxedema [120]. However, more studies addressing these issues are warranted.

Scleredema

Scleredema, also known as scleredema adultorum of Buschke, is a rare sclerotic skin disease occurring with diabetes mellitus, streptococcal infection, and monoclonal gammopathy. The M-protein is usually an IgG, with predominance of kappa light chain over lambda [121,122,123]. An excessive dermal mucin and collagen accumulation lead to a symmetrical widespread, thickening, and non-pitting induration of the skin [124]. Some patients also have a peau d’orange appearance and ulcers (Fig. 7). The condition tends to be chronic and slowly progressive. The skin lesions generally involve the neck, upper trunk, and upper extremities [125]. The histopathology demonstrates thickened reticular dermis with swelling of collagen bundles. The epidermis is usually normal and there is an absence of fibroblast proliferation in contrast to scleromyxedema. There is a lack of evidenced-based treatment of scleredema. Skin-directed therapy can include ultraviolet (UV) light phototherapy (including narrowband UVB or UVA-1). A case report showed significant improvement with bortezomib and intravenous immunoglobulin [126]. In two other cases report, the combination of cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) led to a marked clinical and hematological improvement [127, 128].

TEMPI syndrome

TEMPI syndrome is defined by telangiectasia (T), erythrocytosis with elevated erythropoietin (E), monoclonal M-protein (M), perinephritic fluid collection (P), and intrapulmonary syndrome (I). This is a rare syndrome, described for the first time in 2011 by Sykes & al in four men and two women [129]. The IgG kappa monoclonal protein predominated. However, cases of IgA lambda, IgG lambda, and IgE lambda are also reported. Usually, patients have less than 30 g/L of M-protein spike [130].

The main skin changes associated with TEMPI syndrome are telangiectasias characterized by persistence of dilated capillary vessels with spider-like appearance or small maculopapular red lesions. Telangiectasias are more prominent on the trunk, face, and upper extremities. Erythrocytosis and extremely elevated serum erythropoietic are present in almost all patients. The JAK2 V617F is absent and allows the exclusion of polycythemia vera. The pathogenesis of TEMPI syndrome is poorly understood. It has been hypothesized that erythrocytosis could be explained by renal damage related to monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition resulting in local hypoxia and elevated EPO levels. Plasma cells might also stimulate bone marrow erythroid progenitor cells and thus exacerbate erythrocytosis [130, 131].

Perinephritic fluid collection is associated with palpable abdominal mass, bilateral flank fullness, and hypertension. However, acute renal injury and proteinuria are uncommon manifestations. Kidney biopsy may demonstrate hypertensive vascular change, light chain deposits, and/or amyloidosis [132, 133]. The presence of lymphangiectasia and interstitial edema is less common [133, 134].

Right-to-left intrapulmonary shunt and hypoxemia (oxygen saturation < 90%) are commonly found in patients with TEMPI syndrome. The degree of shunting must be demonstrated with 99mTc macroaggregated albumin scintigraphy. Echocardiography using saline contrast shows late appearance of left-sided bubbles. Patients have progressive dyspnea on exertion and will ultimately need supplemental oxygen [135].

Treatment with bortezomib-based regimens led to eradication of monoclonal gammopathy and complete resolution of all the symptoms associated with the TEMPI syndrome [133, 136, 137]. Bortezomib-based induction followed by autologous stem cell transplantation with high-dose melphalan might be a viable option [138]. Promising responses have been observed with lenalidomide [139] and daratumumab [140].

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak-syndrome (SCLS), also known as Clarkson syndrome, is characterized by generalized edema/anasarca associated with hypovolemia and leakage of intravascular fluid into extravascular space. Less than 260 cases have been reported.

The SCLSC diagnosis criteria are composed of the “3Hs”:

-

1.

Hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg)

-

2.

Hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 49–50% in men and 43–45% in women)

-

3.

Hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 30 g/L).

Episodes of edema are typically recurrent with a quiescent phase [141]. Between 68 and 85% of SCLS patients will have a persistent monoclonal protein, usually IgG or IgA kappa [142]. Pulmonary edema, acute kidney injury, pleural and pericardial effusion are frequent complications. The initial evaluation includes the exclusion of sepsis, anaphylaxis, hereditary angioedema, and proteinuria. In addition, rapid spontaneous recovery in combination with aggressive fluid resuscitation can worsen hypervolemic state and pulmonary edema. Few patients developed compartment syndrome with rhabdomyolysis necessitating fasciotomies [143].

Treatment of acute SCLC includes conservative fluid resuscitation with crystalloids, albumin, and intravenous vasopressors [144]. Intravenous immune globulin (IVIg) may be used in refractory hypotensive patients [145]. Few studies have shown that terbutaline and theophylline administered orally reduced frequency and severity of SCLC episodes. Increasing cyclic AMP activities might reduce inflammatory signal pathways while attenuating endothelial permeability [146,147,148]. Few studies described successful prevention of SCLC episodic frequency with prophylactic IVIG 2 grams/kilogram every month tapered to 1 gram/kilogram every month after achieving remission [149, 150]. No data support the combination of IVIg and terbutaline or theophylline, but this can still be effective.

Acquired Cutis laxa

Acquired cutis laxa is a connective tissue disorder resulting in loose, wrinkled, and redundant skin due to inelastic skin. It can be associated with MGUS, myeloma, lymphoproliferative syndrome, and heavy chain deposition disease [21, 151].

Deposition of immune complexes cause release of inflammatory cytokines which destroy the elastic fibers. Excess of light chains may also alter elastin production by activation of the alternative complement pathway. However, the presence or not of immunoglobulin deposition on elastin fibers in unclear [152, 153]. The generalized form is characterized by hound dog facies following lax skin of the trunk and extremities (Fig. 8). Some localized forms also exists, including distal extremity involvement associated with systemic amyloidosis or multiple myeloma [154]. Very few studies describe stabilization or amelioration of cutis laxa following treatment of the underlying monoclonal gammopathy. Early management with plastic surgery with reconstructive procedures is usually required [155].

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as solitary or multiple lesions. The first description of PG was done by Brunsting, Goeckerman, and O’Leary in 1930 [156]. They believed that a skin infection was the cause of the PG. However, this was a misnomer since PG is not a skin infection nor a classic gangrenous condition. PG can be associated with trauma, inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory arthritis, hematological malignancy, MGUS, and solid malignancy [157, 158]. There is a predominance of IgA gammopathy in patients with monoclonal gammopathy and PG [159].

There are six major clinical variants of pyoderma gangrenosum: ulcerative, bullous, pustular, vegetative, peristomal, and postoperative. The ulcerative PG is the most frequent variant associated with monoclonal gammopathy [160]. PG is generally characterized initially by a pustule with or without peripheral erythema and/or reddish-violaceous appearance. The initial lesion can also be an inflammatory nodule or pustule and it tends to rapidly evolve to erosion and/or necrotic ulcers with violaceous borders and undermined edges [161]. Diagnostic criteria require exclusion of other diagnoses including infection (Table 4) [162].

Achieving remission of the primary hematological malignancy does not always lead to resolution of PG. Combination of systemic and topical corticosteroids is the first line therapy [163]. Cyclosporine is used as an alternative first-line therapy in cases where corticosteroids are contraindicated or as second-line treatment in patients whose disease did not respond to corticosteroids [158, 164]. Biological agents, like infliximab, show promising efficacy with PG. However, their use should be restricted in patients with monoclonal gammopathy since biological agents may promote flare-up of M-protein [165, 166]. Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, danazol, IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra and canakinumab), and azathioprine are options for patients with refractory PG [167,168,169].

Sweet syndrome

Sweet syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is an inflammatory condition associated with autoimmune disease, infections, hematologic malignancies, and solid malignancies. Lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloid leukemia, and hairy cell leukemia are some possible hematologic etiologies. Studies also reported MGUS and multiple myeloma as etiologies of Sweet syndrome [170,171,172,173,174,175,176].

The cutaneous lesions are usually tender, edematous, and erythematous plaques with a symmetric distribution. The lesions are typically localized to the face, trunk, neck, and upper extremities. In patients with malignancies, the lesions may be ulcerated and vesicular (at times localizing to the dorsal hands), or characterized by flaccid bullae and mimic the morphology of pyoderma gangrenosum (bullous variant) [177]. Less common presentations include erythematous nodules (subcutaneous Sweet syndrome) and pustular lesions of the dorsal hands [178, 179].

The major diagnostic criteria of classical Sweet syndrome are shown in Table 5 [180, 181]. Histopathology shows infiltration of neutrophils in the dermis and subcutaneous fat with endothelial swelling, and prominent edema in the superficial dermis. There is an absence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. First-line treatments are high-potency topical or systemic corticosteroids. Potassium iodide, dapsone, and colchicine may also be used due to their anti-neutrophilic activity [182].

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED)

EED is a rare chronic dermatosis. The skin lesions are described as red-brown, violaceous or yellow papules, plaques, or nodules (Fig. 9). EED mostly involves the extensor surfaces of joints, axilla, posterior auricular area, buttocks, soles, larynx, and acral sites. Atypical presentations as annular lesions or verrucous plaques are also seen [183,184,185,186,187,188].

EED is associated with monoclonal gammopathy, more frequently IgA MGUS [185] or multiple myeloma [189, 190]. EED is also found with HIV infection [191, 192], tuberculosis [193], hepatitis B infection [192], myelodysplastic syndrome [194], lymphoma [195], and autoimmune disease [190].

Some patients with EED will have extracutaneous manifestations, including arthralgia, scleritis, panuveitis, ulcerative keratitis, neuropathy, and ulceration. On histopathology, early lesions demonstrate neutrophilic infiltration and typical leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the upper dermis to the mid-dermis [190]. With the progression of the disease, the papillary and periadnexal dermis become involved. Granulation tissue, xanthomatization, and storiform fibrosis are also seen [185, 196, 197]. Dapsone is the preferred first-line treatment and is associated with improvement of cutaneous and extracutaneous symptoms (although late nodular cutaneous lesions may be more recalcitrant to treatment).

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (SPD) is a neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by a relapsing asymptomatic eruption of superficial pustules occurring predominantly in intertriginous sites. SPD involves the trunk, axillae, groin, abdomen and flexural aspect of the proximal extremities. The pustules normally measure a few millimeters in diameter, but can be larger and become flaccid bullae, called “half-half” blisters (with clear fluid on the superior portion and pus on the inferior portion, also known as “hypopyon”) [198].

SPD frequently is a chronic benign disease. However, SPD is also found in patients with monoclonal gammopathy, usually IgA gammopathy [199,200,201,202]. The treatment of choice for SPD is dapsone [203].

Perspective on cutaneous manifestations of gammopathy

Cutaneous manifestations of monoclonal gammopathy are an oftentimes overlooked manifestation of clonal proliferative dyscrasia. These cutaneous manifestations are associated with heterogeneous clinical manifestations and prognosis (Table 6). The treatment depends mainly on the severity of the cutaneous disease (Table 7). We sought to clarify the classification and cutaneous manifestations of monoclonal gammopathy, while extending the concept of monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance. Additional studies are needed to investigate the pathogenesis of monoclonal gammopathy-associated skin disease and therapy options.

References

Kyle RA, Larson DR, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Cerhan JR, et al. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:241–9.

Fermand JP, Bridoux F, Dispenzieri A, Jaccard A, Kyle RA, Leung N, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance: a novel concept with therapeutic implications. Blood. 2018;132:1478–85.

Daoud MS, Lust JA, Kyle RA, Pittelkow MR. Monoclonal gammopathies and associated skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:507–35.

Dispenzieri A. POEMS Syndrome: 2019 Update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:812–27.

Abe D, Nakaseko C, Takeuchi M, Tanaka H, Ohwada C, Sakaida E, et al. Restrictive usage of monoclonal immunoglobulin lambda light chain germline in POEMS syndrome. Blood. 2008;112:836–9.

Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Lacy MQ, Rajkumar SV, Therneau TM, Larson DR, et al. POEMS syndrome: Definitions and long-term outcome. Blood. 2003;101:2496–506.

Miest RY, Comfere NI, Dispenzieri A, Lohse CM, el-Azhary RA. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with POEMS syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1349–56.

Tsai CY, Lai CH, Chan HL, Kuo T. Glomeruloid hemangioma-a specific cutaneous marker of POEMS syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:403–6.

Barete S, Mouawad R, Choquet S, Viala K, Leblond V, Musset L, et al. Skin manifestations and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in POEMS syndrome: impact of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:615–23.

Yoshikawa M, Uhara H, Arakura F, Murata H, Kubo H, Takata M, et al. Calciphylaxis in POEMS syndrome: A case treated with etidronate. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:98–9.

Araki N, Misawa S, Shibuya K, Ota S, Oide T, Kawano A, et al. POEMS syndrome and calciphylaxis: An unrecognized cause of abnormal small vessel calcification. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:35.

Pihan M, Keddie S, D’Sa S, Church AJ, Yong KL, Reilly MM, et al. Raised VEGF: High sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5:e486.

Lachgar S, Moukadiri H, Jonca F, Charveron M, Bouhaddioui N, Gall Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine growth factor for hair dermal papilla cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:17–23.

Kim EH, Kim YC, Lee ES, Kang HY. The vascular characteristics of melasma. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;46:111–6.

Atkinson S, Fox SB. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) play a central role in the pathogenesis of digital clubbing. J Pathol. 2004;203:721–8.

Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flt-1, in glomeruloid haemangioma associated with Crow-Fukase syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:417–9.

Humeniuk MS, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Kyle RA, Witzig TE, Kumar SK, et al. Outcomes of patients with POEMS syndrome treated initially with radiation. Blood. 2013;122:68–73.

Nozza A, Terenghi F, Gallia F, Adami F, Briani C, Merlini G, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with POEMS syndrome: Results of a prospective, open-label trial. Br J Haematol. 2017;179:748–55.

Dispenzieri A, Klein CJ, Mauermann ML. Lenalidomide therapy in a patient with POEMS syndrome. Blood. 2007;110:1075–6.

Zhao H, Huang XF, Gao XM, Cai H, Zhang L, Feng J, et al. What is the best first-line treatment for POEMS syndrome: Autologous transplantation, melphalan and dexamethasone, or lenalidomide and dexamethasone? Leukemia. 2019;33:1023–9.

Alegría-Landa V, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, Requena L. Paraprotein deposits in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1145–58.

Cobb MW, Domloge-Hultsch N, Frame JN, Yancey KB. Waldenström macroglobulinemia with an IgM-kappa antiepidermal basement membrane zone antibody. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:372–6.

Whittaker SJ, Bhogal BS, Black MM. Acquired immunobullous disease: A cutaneous manifestation of IgM macroglobulinaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:283–6.

Pech JH, Moreau-Cabarrot A, Oksman F, Bedane C, Bernard P, Bazex J. Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia with antibasement membrane activity of monoclonal immunoglobulin. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1997;124:325–8.

West NY, Fitzpatrick JE, David-Bajar KM, Bennion SD. Waldenström macroglobulinemia-induced bullous dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1127–31.

Gressier L, Hotz C, Lelièvre J-D, Carlotti A, Buffet M, Wolkenstein P, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: A report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:165–9.

Chattopadhyay M, Rytina E, Dada M, Bhogal BS, Groves R, Handfield-Jones S. Immunobullous dermatosis associated with Waldenström macroglobulinaemia treated with rituximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:866–9.

Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2020 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:848–60.

Agarwal A, Chang DS, Selim MA, Penrose CT, Chudgar SM, Cardones AR. Pinch purpura: A cutaneous manifestation of systemic amyloidosis. Am J Med. 2015;128:e3–4.

Galvez-Cardenas KM, Varela DC. Uvula amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:577.

Merlini G, Seldin DC, Gertz MA. Amyloidosis: Pathogenesis and new therapeutic options. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1924–33.

Liebman HA, Carfagno MK, Weitz IC, Berard P, Diiorio JM, Vosburgh E, et al. Excessive fibrinolysis in amyloidosis associated with elevated plasma single-chain urokinase. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98:534–41.

Liebman H, Chinowsky M, Valdin J, Kenoyer G, Feinstein D. Increased fibrinolysis and amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:678–82.

Jo G, Shin DY, Mun JH. Systemic amyloidosis-induced nail dystrophy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:1057–9.

Glenner GG. Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis. The beta-fibrilloses (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1283–92.

Brambilla F, Lavatelli F, Di Silvestre D, Valentini V, Rossi R, Palladini G, et al. Reliable typing of systemic amyloidoses through proteomic analysis of subcutaneous adipose tissue. Blood. 2012;119:1844–7.

Klein CJ, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Dyck PJ, Dyck PJ, Spinner RJ, et al. Mass spectrometric-based proteomic analysis of amyloid neuropathy type in nerve tissue. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:195–9.

Vrana JA, Gamez JD, Madden BJ, Theis JD, Bergen HR 3rd, Dogan A. Classification of amyloidosis by laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis in clinical biopsy specimens. Blood. 2009;114:4957–9.

Huang X, Wang Q, Chen W, Zeng C, Chen Z, Gong D, et al. Induction therapy with bortezomib and dexamethasone followed by autologous stem cell transplantation versus autologous stem cell transplantation alone in the treatment of renal AL amyloidosis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2014;12:2.

Scott EC, Heitner SB, Dibb W, Meyers G, Smith SD, Abar F, et al. Induction bortezomib in Al amyloidosis followed by high dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation: a single institution retrospective study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:424–30.e1.

Cornell RF, Fraser R, Costa L, Goodman S, Estrada-Merly N, Lee C, et al. Bortezomib-based induction is associated with superior outcomes in light chain amyloidosis patients treated with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation regardless of plasma cell burden. Transpl Cell Ther. 2021;27:264.e1–.e7.

Oke O, Sethi T, Goodman S, Phillips S, Decker I, Rubinstein S, et al. Outcomes from autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation versus chemotherapy alone for the management of light chain amyloidosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:1473–7.

Landau H, Hassoun H, Rosenzweig MA, Maurer M, Liu J, Flombaum C, et al. Bortezomib and dexamethasone consolidation following risk-adapted melphalan and stem cell transplantation for patients with newly diagnosed light-chain amyloidosis. Leukemia. 2013;27:823–8.

Palladini G, Kastritis E, Maurer MS, Zonder J, Minnema MC, Wechalekar AD, et al. Daratumumab plus CyBorD for patients with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis: safety run-in results of ANDROMEDA. Blood. 2020;136:71–80.

Palladini G, Milani P, Merlini G. Management of AL amyloidosis in 2020. Blood. 2020;136:2620–7.

Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, Aucouturier F, Galicier L, Asli B, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: A study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671–8.

Dammacco F, Sansonno D, Piccoli C, Tucci FA, Racanelli V. The cryoglobulins: An overview. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:628–38.

Trejo O, Ramos-Casals M, García-Carrasco M, Yagüe J, Jiménez S, de la Red G, et al. Cryoglobulinemia: Study of etiologic factors and clinical and immunologic features in 443 patients from a single center. Medicine. 2001;80:252–62.

Saadoun D, Sellam J, Ghillani-Dalbin P, Crecel R, Piette JC, Cacoub P. Increased risks of lymphoma and death among patients with non-hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2101–8.

Morra E. Cryoglobulinemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;1:368–72.

Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, Alapat D, Usmani SZ. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395–400.

Cohen SJ, Pittelkow MR, Su WP. Cutaneous manifestations of cryoglobulinemia: Clinical and histopathologic study of seventy-two patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:21–7.

Letendre L, Kyle RA. Monoclonal cryoglobulinemia with high thermal insolubility. Mayo Clin Proc. 1982;57:629–33.

Mattuci-Cerinic M, Furst D, Fiorentino D, Wetter DA. Skin manifestations in rheumatic disease. Darent Valley Hospital, Dartford, United Kingdom: Springer; 2014. p. 427.

Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289–98.

Quartuccio L, Soardo G, Romano G, Zaja F, Scott CA, De Marchi G, et al. Rituximab treatment for glomerulonephritis in HCV-associated mixed cryoglobulinaemia: efficacy and safety in the absence of steroids. Rheumatology 2006;45:842–6.

Roccatello D, Baldovino S, Rossi D, Mansouri M, Naretto C, Gennaro M, et al. Long-term effects of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment of cryoglobulinaemic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:3054–61.

Kanoh T, Takigawa M, Niwa Y. Cutaneous lesions in gamma heavy-chain disease. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1538–40.

Mozzanica N, Finzi AF, Facchetti G, Villa ML. Macular skin lesion and monoclonal lymphoplasmacytoid infiltrates. Occurrence in primary Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:778–81.

Hobbs JR, Corbett AA. Younger age of presentation and extraosseous tumour in IgD myelomatosis. Br Med J. 1969;1:412–4.

Marzolf G, Lenormand C, Michel C, Cribier B, Lipsker D. Adenopathy and extensive skin patch overlying a plasmacytoma (AESOP): Two morphologic variants can be outlined. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1286–7.

Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, Calonje E, Requena C, Pérez G, et al. Cutaneous involvement in multiple myeloma: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic study of 8 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:475–86.

Jorizzo JL, Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Cutaneous plasmacytomas. A review and presentation of an unusual case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:59–66.

Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V, Sun A. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: A case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:e630–e46.

Schnitzler L. Lesions urticariennes chroniques permanentes (erytheme petaloide?). Cas cliniques n. 46 B. Jounee Dermatologique d’Angers. 1972.

Kacar M, Pathak S, Savic S. Hereditary systemic autoinflammatory diseases and Schnitzler’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 2019;58:vi31–vi43.

de Koning HD. Schnitzler’s syndrome: Lessons from 281 cases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:41.

Pathak S, Rowczenio DM, Owen RG, Doody GM, Newton DJ, Taylor C, et al. Exploratory study of MYD88 L265P, rare NLRP3 variants, and clonal hematopoiesis prevalence in patients with Schnitzler syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:2121–5.

Ryan JG, de Koning HD, Beck LA, Booty MG, Kastner DL, Simon A. IL-1 blockade in Schnitzler syndrome: Ex vivo findings correlate with clinical remission. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:260–2.

de Koning HD, Schalkwijk J, Stoffels M, Jongekrijg J, Jacobs JF, Verwiel E, et al. The role of interleukin-1 beta in the pathophysiology of Schnitzler’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:187.

Krause K, Sabat R, Witte-Händel E, Schulze A, Puhl V, Maurer M, et al. Association of CCL2 with systemic inflammation in Schnitzler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:859–68.

Sokumbi O, Drage LA, Peters MS. Clinical and histopathologic review of Schnitzler syndrome: The Mayo Clinic experience (1972–2011). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1289–95.

Kieffer C, Cribier B, Lipsker D. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis: a variant of neutrophilic urticaria strongly associated with systemic disease. Report of 9 new cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2009;88:23–31.

Simon A, Asli B, Braun-Falco M, De Koning H, Fermand JP, Grattan C, et al. Schnitzler’s syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Allergy. 2013;68:562–8.

Dybowski F, Sepp N, Bergerhausen HJ, Braun J. Successful use of anakinra to treat refractory Schnitzler’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:354–7.

Cascavilla N, Bisceglia M, D’Arena G. Successful treatment of Schnitzler’s syndrome with anakinra after failure of rituximab trial. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:633–6.

Besada E, Nossent H. Dramatic response to IL1-RA treatment in longstanding multidrug resistant Schnitzler’s syndrome: A case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:567–71.

Néel A, Henry B, Barbarot S, Masseau A, Perrin F, Bernier C, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in Schnitzler’s syndrome: a French multicenter study. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1035–41.

Krause K, Tsianakas A, Wagner N, Fischer J, Weller K, Metz M, et al. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in Schnitzler syndrome: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1311–20.

Krause K, Weller K, Stefaniak R, Wittkowski H, Altrichter S, Siebenhaar F, et al. Efficacy and safety of the interleukin-1 antagonist rilonacept in Schnitzler syndrome: An open-label study. Allergy. 2012;67:943–50.

Inthasotti S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Manonukul J. A 7-year history of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma following asymptomatic multiple myeloma: A case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:927852.

Finan MC, Winkelmann RK. Histopathology of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:92–9.

Fortson JS, Schroeter AL. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with IgA paraproteinemia and extracutaneous involvement. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:579–84.

Lopes S, Gomes N, César A, Barros AM, Pinheiro J, Azevedo F. An exuberant case of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:83–6.

Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1–10.

Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, Reeder CB. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471–9.

Ryan E, Warren LJ, Szabo F. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: Response to chlorambucil. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:e23–5.

Miguel D, Lukacs J, Illing T, Elsner P. Treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma—A systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:221–35.

Plotnick H, Taniguchi Y, Hashimoto K, Negendank W, Tranchida L. Periorbital necrobiotic xanthogranuloma and stage I multiple myeloma. Ultrastructure and response to pulsed dexamethasone documented by magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:373–7.

Chave TA, Chowdhury MM, Holt PJ. Recalcitrant necrobiotic xanthogranuloma responding to pulsed high-dose oral dexamethasone plus maintenance therapy with oral prednisolone. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:158–61.

Hallermann C, Tittelbach J, Norgauer J, Ziemer M. Successful treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with intravenous immunoglobulin. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:957–60.

Rubinstein A, Wolf DJ, Granstein RD. Successful treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:347–50.

Pedrosa AF, Ferreira O, Calistru A, Mota A, Baudrier T, Sarmento JA, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with giant cell hepatitis, successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:68–70.

Mahendran P, Wee J, Chong H, Natkunarajah J. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma treated with lenalidomide. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:345–7.

Wei YH, Cheng JJ, Wu YH, Liu CY, Hung CJ, Hsu JD, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: response to dapsone. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:7–9.

Klingner M, Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Wollina U. Disseminated necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Hautarzt. 2016;67:902–6.

Cohen YK, Elpern DJ. Diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Dermatol Pr Concept. 2015;5:65–7.

Szalat R, Arnulf B, Karlin L, Rybojad M, Asli B, Malphettes M, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of xanthomatosis associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Blood. 2011;118:3777–84.

Kim JG, Kim HR, You MH, Shin DH, Choi JS, Bae YK. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma coexists with diffuse normolipidemic plane xanthoma and multiple myeloma. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32:53–6.

Lorenz S, Hohenleutner S, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Treatment of diffuse plane xanthoma of the face with the Erbium:YAG laser. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1413–5.

Dubreuilh W. Fibromes miliaires folliculaires: Sclerodermie consecutive. Ann Dermatol Syph. 1906;37:569–72.

Reitmann K. Über eine eigenartige, der Sklerodermie nahestehende Affektion. Arch für Dermatologie und Syph. 1908;92:417–24.

Hoffmann JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449–67.

Rongioletti F, Hazini A, Rebora A. Coma associated with scleromyxoedema and interferon alfa therapy. Full recovery after steroids and cyclophosphamide combined with plasmapheresis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1283–4.

Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, Langley R, Corbin J, Pasternak S, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508–17.

Espinosa A, De Miguel E, Morales C, Fonseca E, Gijón-Baños J. Scleromyxedema associated with arthritis and myopathy: A case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993;11:545–7.

Jamieson TW, De Smet AA, Stechschulte DJ. Erosive arthropathy associated with scleromyxedema. Skelet Radiol. 1985;14:286–90.

De Simone C, Castriota M, Carbone A, Marini Bettolo P, Pieroni M, Rongioletti F. Cardiomyopathy in scleromyxedema: Report of a fatal case. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:852–3.

Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658–62.

Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273–81.

Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, Fausti V, Cozzani E, Cribier B, et al. Scleromyxedema: A multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66–72.

Guarneri A, Cioni M, Rongioletti F. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for scleromyxoedema: a prospective open-label clinical trial using an objective score of clinical evaluation system. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1157–60.

Mecoli CA, Talbot CC Jr., Fava A, Cheadle C, Boin F, Wigley FM, et al. Clinical and Molecular Phenotyping in Scleromyxedema Pretreatment and Posttreatment With Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72:761–7.

Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: A systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191–201.

Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, Kreuter A, Cozzio A, Mouthon L, et al. European dermatology forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, Part 2: Scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581–94.

Brunet-Possenti F, Hermine O, Marinho E, Crickx B, Descamps V. Combination of intravenous immunoglobulins and lenalidomide in the treatment of scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:319–20.

Migkou M, Gkotzamanidou M, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E. Response to bortezomib of a patient with scleromyxedema refractory to other therapies. Leuk Res. 2011;35:e209–11.

Fett NM, Toporcer MB, Dalmau J, Shinohara MM, Vogl DT. Scleromyxedema and dermato–neuro syndrome in a patient with multiple myeloma effectively treated with dexamethasone and bortezomib. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:893–6.

Yeung CK, Loong F, Kwong YL. Scleromyxoedema due to a plasma cell neoplasm: Rapid remission with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:411.

Win H, Gowin K. Treatment of scleromyxedema with lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:3043–9.

Hodak E, Tamir R, David M, Hart M, Sandbank M, Pick A. Scleredema adultorum associated with IgG-kappa multiple myeloma-a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:271–4.

Venencie PY, Powell FC, Su WP. Scleredema and monoclonal gammopathy: Report of two cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:554–6.

Ohta A, Uitto J, Oikarinen AI, Palatsi R, Mitrane M, Bancila EA, et al. Paraproteinemia in patients with scleredema. Clinical findings and serum effects on skin fibroblasts in vitro. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:96–107.

Rongioletti F, Kaiser F, Cinotti E, Metze D, Battistella M, Calzavara-Pinton PG, et al. Scleredema. A multicentre study of characteristics, comorbidities, course and therapy in 44 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2399–404.

Ng E, Rosenstein R, Terushkin V, Meehan S, Pomeranz MK. Idiopathic scleredema. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8dj6589j.

Keragala B, Herath H, Janappriya G, Dissanayaka BS, Shyamini SC, Liyanagama DP, et al. Scleredema associated with immunoglobulin A-κ smoldering myeloma: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:145.

Ibrahim RA, Abdalla NEH, Shabaan EAH, Mostafa NBH. An unusual presentation of a rare scleroderma mimic: What is behind the scenes? Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2019;15:172–5.

Szturz P, Adam Z, Vašků V, Feit J, Krejčí M, Pour L, et al. Complete remission of multiple myeloma associated scleredema after bortezomib-based treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:1324–6.

Sykes DB, Schroyens W, O’Connell C. The TEMPI syndrome-a novel multisystem disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:475–7.

Zhang X, Fang M. TEMPI syndrome: Erythrocytosis in plasma cell dyscrasia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:724–30.

Rosado FG, Oliveira JL, Sohani AR, Schroyens W, Sykes DB, Kenderian SS, et al. Bone marrow findings of the newly described TEMPI syndrome: When erythrocytosis and plasma cell dyscrasia coexist. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:367–72.

Mohammadi F, Wolverson MK, Bastani B. A new case of TEMPI syndrome. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:556–8.

Jasim S, Mahmud G, Bastani B, Fesler M. Subcutaneous bortezomib for treatment of TEMPI syndrome. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:e221–3.

Viglietti D, Sverzut JM, Peraldi MN. Perirenal fluid collections and monoclonal gammopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:448–9.

Glavey SV, Leung N. Monoclonal gammopathy: The good, the bad and the ugly. Blood Rev. 2016;30:223–31.

Kwok M, Korde N, Landgren O. Bortezomib to treat the TEMPI syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1843–5.

Schroyens WA, O’Connell CL, Lacy MQ, Attar EC, Raje N, Somer BG, et al. TEMPI: A reversible syndrome following treatment with bortezomib. Blood. 2012;120:986.

Kenderian SS, Rosado FG, Sykes DB, Hoyer JD, Lacy MQ. Long-term complete clinical and hematological responses of the TEMPI syndrome after autologous stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2015;29:2414–6.

Liang SH, Yeh SP. Relapsed multiple myeloma as TEMPI syndrome with good response to salvage lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Ann Hematol. 2019;98:2447–50.

Sykes DB, Schroyens W. Complete responses in the TEMPI syndrome after treatment with daratumumab. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2240–2.

Kapoor P, Greipp PT, Schaefer EW, Mandrekar SJ, Kamal AH, Gonzalez-Paz NC, et al. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (Clarkson’s disease): the Mayo clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:905–12.

Zhang W, Ewan PW, Lachmann PJ. The paraproteins in systemic capillary leak syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93:424–9.

Druey KM, Parikh SM. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (Clarkson disease). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:663–70.

Atkinson JP, Waldmann TA, Stein SF, Gelfand JA, Macdonald WJ, Heck LW, et al. Systemic capillary leak syndrome and monoclonal IgG gammopathy; studies in a sixth patient and a review of the literature. Medicine. 1977;56:225–39.

Lambert M, Launay D, Hachulla E, Morell-Dubois S, Soland V, Queyrel V, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins dramatically reverse systemic capillary leak syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2184–7.

Amoura Z, Papo T, Ninet J, Hatron PY, Guillaumie J, Piette AM, et al. Systemic capillary leak syndrome: Report on 13 patients with special focus on course and treatment. Am J Med. 1997;103:514–9.

Dowden AM, Rullo OJ, Aziz N, Fasano MB, Chatila T, Ballas ZK. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome: Novel therapy for acute attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1111–3.

Dhir V, Arya V, Malav IC, Suryanarayanan BS, Gupta R, Dey AB. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS): Case report and systematic review of cases reported in the last 16 years. Intern Med. 2007;46:899–904.

Marra AM, Gigante A, Rosato E. Intravenous immunoglobulin in systemic capillary leak syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:349–52.

Gousseff M, Arnaud L, Lambert M, Hot A, Hamidou M, Duhaut P, et al. The systemic capillary leak syndrome: A case series of 28 patients from a European registry. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:464–71.

Majithia RA, George L, Thomas M, Fouzia NA. Acquired cutis laxa associated with light and heavy chain deposition disease. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:44–6.

Gverić T, Barić M, Bulat V, Situm M, Pusić J, Huljev D, et al. Clinical presentation of a patient with localized acquired cutis laxa of abdomen: A case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:402093.

Yadav TA, Dongre AM, Khopkar US. Acquired cutis laxa of face with multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:454–6.

Vork DL, Shah KK, Youssef MJ, Wieland CN. Acral localized acquired cutis laxa as presenting sign of underlying systemic amyloidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1050–3.

Shalhout SZ, Nahas MR, Drews RE, Miller DM. Generalized acquired cutis laxa associated with monoclonal gammopathy of dermatological significance. Case Rep. Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:7480607.

Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’LEARY PA. Pyoderma (echthyma) gangrenosum: Clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743–68.

Ashchyan HJ, Butler DC, Nelson CA, Noe MH, Tsiaras WG, Lockwood SJ, et al. The association of age with clinical presentation and comorbidities of pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:409–13.

Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Li VW, Winterfield LS. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A retrospective review of patient characteristics, comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1244–50.

Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Su WPD, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum and monoclonal gammopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:468–72.

Yoon YH, Cho WI, Seo SJ. Case of multiple myeloma associated with extramedullary cutaneous plasmacytoma and pyoderma gangrenosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:594–7.

Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, Callen JP, Brüggen M-C, Guenova E, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:81.

Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, Fiorentino D, Callen JP, Wollina U, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: A Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461–6.

Romańska-Gocka K, Cieścińska C, Zegarska B, Schwartz RA, Cieściński J, Olszewska-Słonina D, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum with monoclonal IgA gammopathy and pulmonary tuberculosis. Illustrative case and review. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:137–41.

Ormerod AD, Thomas KS, Craig FE, Mitchell E, Greenlaw N, Norrie J, et al. Comparison of the two most commonly used treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: Results of the STOP GAP randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2015;350:h2958.

Shareef MS, Munro LR, Owen RG, Highet AS. Progression of IgA gammopathy to myeloma following infliximab treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:146–8.

Smale SW, Lawson TM. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and anti-TNF-alpha treatment. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36:405–6.

Wollina U. Clinical management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:149–58.

Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: A comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:191–211.

Kolios AG, Maul JT, Meier B, Kerl K, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Hertl M, et al. Canakinumab in adults with steroid-refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1216–23.

Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: A clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:503–7.

Vignon-Pennamen MD, Wallach D. Cutaneous manifestations of neutrophilic disease. A study of seven cases. Dermatologica. 1991;183:255–64.

Bunker CB. Sweet’s syndrome associated with IgG paraproteinaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:135.

Ribeiro A, Costa J, Bogas M, Costa L, Araújo D. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis—Sweet’s syndrome. Acta Reumatol Port. 2009;34:536–40.

Apted JH. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) associated with multiple myeloma. Australas J Dermatol. 1984;25:15–7.

Berth-Jones J, Hutchinson PE. Sweet’s syndrome and malignancy: A case associated with multiple myeloma and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:123–7.

Torralbo A, Herrero JA, del-Rio E, Sanchez-Yus E, Barrientos A. Sweet’s syndrome associated with multiple myeloma. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:297–8.

Voelter-Mahlknecht S, Bauer J, Metzler G, Fierlbeck G, Rassner G. Bullous variant of Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:946–7.

Guhl G, García-Díez A. Subcutaneous sweet syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:541–51.

Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, Piette WW. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and sweet syndrome: Report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57–63.

Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:918–23.

Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: Systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234–40.

Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome: A review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:117–31.

Di Giacomo TB, Marinho RT, Nico MM. Erythema elevatum diutinum presenting with a giant annular pattern. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:290–2.

Barzegar M, Davatchi CC, Akhyani M, Nikoo A, Daneshpazhooh M, Farsinejad K. An atypical presentation of erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:73–5.

Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: A clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38–44.

Mraz JP, Newcomer VD. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Presentation of a case and evaluation of laboratory and immunological status. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:235–46.

Keyal U, Bhatta AK, Liu Y. Erythema elevatum diutinum involving palms and soles: A case report and literature review. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:1956–9.

Gi AL, Aljarbou OZ, A AL, AlJasser MI. Atypical palmar involvement with erythema elevatum diutinum as a sole manifestation: A report of two cases. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:529–35.

Archimandritis AJ, Fertakis A, Alegakis G, Bartsokas S, Melissinos K. Erythema elevatum diutinum and IgA myeloma: An interesting association. Br Med J. 1977;2:613–4.

Sandhu JK, Albrecht J, Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Erythema elevatum et diutinum as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:679–83.

Smitha P, Sathish P, Mohan K, Sripathi H, Sachi G. A case of extensive erosive and bullous erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:989–91.

Soni BP, Williford PM, White WL. Erythematous nodules in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:232–3. 5-6

Doktor V, Hadi A, Hadi A, Phelps R, Goodheart H. Erythema elevatum diutinum: A case report and review of literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:408–15.

Agha A, Bateman H, Sterrett A, Valeriano-Marcet J. Myelodysplasia and malignancy-associated vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:526–31.

Futei Y, Konohana I. A case of erythema elevatum diutinum associated with B-cell lymphoma: a rare distribution involving palms, soles, and nails. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:116–9.

Shahidi-Dadras M, Asadi Kani Z, Mozafari N, Dadkhahfar S. The late stage of erythema elevatum diutinum mimicking cutaneous spindle-cell neoplasms: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:551–4.

Shi KY, Vandergriff T. Late-stage nodular erythema elevatum diutinum mimicking sclerotic fibroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:94–6.

O’Connell M, Goulden V. Images in clinical medicine. “Half-half” blisters. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:e31.

Lautenschlager S, Itin PH, Hirsbrunner P, Büchner SA. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis at the injection site of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in a patient with IgA myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:787–9.

Takata M, Inaoki M, Shodo M, Hirone T, Kaya H. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis associated with IgA myeloma and intraepidermal IgA deposits. Dermatology. 1994;189:111–4.

Vaccaro M, Cannavò SP, Guarneri B. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis and IgA lambda myeloma: A uncommon association but probably not coincidental. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:644–6.

Kasha EE Jr., Epinette WW. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson disease) in association with a monoclonal IgA gammopathy: A report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:854–8.

Cheng S, Edmonds E, Ben-Gashir M, Yu RC. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: 50 years on. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:229–33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JSC drafting the article. DW and SK critical revision of the work and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Claveau, JS., Wetter, D.A. & Kumar, S. Cutaneous manifestations of monoclonal gammopathy. Blood Cancer J. 12, 58 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00661-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00661-1