Abstract

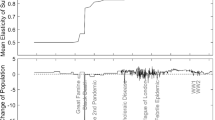

This paper builds an age-structured model of human population genetics in which explicit individual choices drive the dynamics via sexual selection. In the model, agents are endowed with a high-dimensional genome that determines their cognitive and physical characteristics. Young adults optimally search for a marriage partner, work for firms, consume goods, save for old age and, if married, decide how many children to have. In accord with the fundamental genetic operators, children receive genes from their parents. An agent's human capital (productivity) is an aggregate of the received genetic endowment and environmental influences so that the population of agents and the economy co-evolve. After calibrating the model, we examine the impact of physical, social, and economic institutions on population growth and economic performance. We find that institutional factors significantly impact economic performance by affecting marriage, family size, and the intergenerational transmission of genes. The principal novel findings are that i) genetic diversity has a nonmonotone causal impact on population size and economic performance; ii) an endogenous population threshold exists which, absent frictions, causes societies with declining populations and output to reverse course and grow; and iii) that the emotion love substantially accelerates economic growth by increasing genetic diversity ‘just enough’, which we term ‘The Goldilocks Principle’.

Similar content being viewed by others

References cited

Ackerman, Diane. 1995. A natural history of love. Vintage Books, New York.

Aiyagari, S. Rao, Jeremy Greenwood & Nezih Guner. 2000. On the state of the union. Journal of Political Economy 108(2):213–244.

Ashenfelter, Orley & Cecilia Rouse. 1998. Income, schooling, and ability: evidence from a new sample of identical twins. Quarterly Journal of Economics 452:253–284.

Azariadis, Costas. 1996. The economics of poverty traps, part one: complete markets. Journal of Economic Growth 1(4):449–486.

Azariadis, Costas. 1993. Intertermporal macroeconomics. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Bala, Venkatesh & Gerhard Sorger. 1998. The evolution of human capital in an interacting agent economy. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 36(1):85–108.

Banzhaf, Wolfgang & Frank H. Eeckman (ed.) 1995. Evolution and biocomputation: computational models of evolution. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Bartel, Ann P. & Nachum Sicherman. 1999. Technological change and wages: an interindustry analysis. Journal of Political Economy 107(2):285–325.

Becker, Gary S. 1973. A theory of marriage: part I. Journal of Political Economy 81(4):813–846.

Becker, Gary S. 1974. A theory of marriage: part II. Journal of Political Economy 82(2):S11-S26.

Becker, Gary S. 1993. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. 3rd ed. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Becker, Gary S. & Nigel Tomes. 1976. Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy 84(4):S143-S162.

Becker, Gary S. & Robert Barro. 1988. A reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Quarterly Journal of Economics 53(1):1–25.

Becker, Gary S., Kevin M. Murphy & Robert Tamura. 1990. Human capital, fertility, and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy 98(5(2)):S12-S37.

Behrman, Jere. Mark R. Rosenzweig & Paul Taubman. 1994. Endowments and the allocation of schooling in the family and in the marriage market: the twins experiment. Journal of Political Economy 102(6): 1131–1174.

Behrman, Jere & Paul Taubman. 1989. Is schooling ‘mostly in the genes’? nature-nurture decomposition using data on relatives. Journal of Political Economy 97(6):1425–1446.

Behrman, Jere, Zdenek Hrubec, Paul Taubman & Terrence. J. Wales. 1980. Socioeconomic success: a study of the effects of genetic endowments, family environment, and schooling. North-Holland Publishers, New York.

Birdsall, Nancy. 1988. Economic approaches to population growth. Pp. 477–542 in H. Chenery & T.N. Srivivasan. (ed.) Handbook of Development Economics. Vol. 1, Elsevier Science Publishers, New York.

Boccaccio, Giovanni. 1351/1989. The decameron. Mark Musa and Peter Bondanella, trans., New American Library, New York.

Brody, Nathan. 1992. Intelligence, 2nd ed. Academic Press, New York.

Burdett, Ken & Melvyn G. Coles. 1997. Marriage and class. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(1):141–168.

Burdett, Ken & Melvyn G. Coles. 1999. Long-term partnership formation: marriage and employment. Economic Journal 10(456):F307-F334.

Buss, David M. & 49 co-authors. 1990. International preferences selecting mates: a study of 37 cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 21(1):5–47.

Buss, David M. 1994. The evolution of desire. Basic Books, New York.

Buss, David M. & Michael Barnes. 1986. Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50(3):559–570.

Buss, David M. 1989. Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12:1–49.

Cooley, Thomas (ed.) 1995. Frontiers of business cycle research. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Cosmides, Leda & John Tooby. 1995. Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. Pp. 163–228 in J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides & J. Tooby (ed.) The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, Oxford University Press Paperback, Oxford.

Darwin, Charles. 1871/1981. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The selfish gene. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Diamond, Peter. 1965. National debt in a neoclassical growth model. American Economic Review 55:1026–1055.

Downey, Douglas B. 1995. When bigger is not better: family size, parental resources, and children's educational performance. American Sociological Review 60:746–761.

Edelman, Gerald M. 1992. Bright air, brilliant fire: on the matter of the mind. Basic Books, New York.

Emlen, John Merritt. 1984. Population biology: the coevolution of population dynamics and behavior. Macmillian Publishing, New York.

Feng, Yi, Jacek Kugler & Paul J. Zak. 2000. The politics of fertility and economic development. International Studies Quarterly 44(2):667–694.

Forbes, Kristin. J. 2000. A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth. American Economic Review 90(4):869–887.

Flynn, James R. 1987. Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: what IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin 101(2):171–191.

Frank, Robert J. 1988. Passions within reason: the strategic role of the emotions. Norton, New York.

Galor, Oded & Joseph Zeira. 1993. Income distribution and macroeconomics. Review of Economic Studies 60:35–52.

Galor, Oded & David Weil. 1996. The gender gap, fertility, and growth. American Economic Review 86(3):374–387.

Galor, Oded & Daniel Tsiddon. 1997a. The distribution of human capital and economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth 2:93–124.

Galor, Oded & Daniel Tsiddon. 1997b. Technological progress, mobility, and economic growth. American Economic Review 87(3):363–382.

Gazzaniga, Michael S. 1992. Nature's mind: the biological roots of thinking, emotions, sexuality, language, and intelligence. Basic Books, New York.

Geddes, Rick & Paul J. Zak. 2002. The rule of one-third. Journal of Legal Studies, forthcoming.

Ginzberg, Lev R. 1983. Theory of natural selection and population growth. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing, Menlo Park.

Graefen, Alan. 2000. The biological approach to economics through fertility. Economics Letters 66:241–248.

Graefen, Alan. 1998. Fertility and labour supply in femina economica. Journal of Theoretical Biology 3:383–407.

Greenwood, Jeremy, Nezih Guner & John Knowles. 1999. More on marriage, fertility, and the distribution of income. Working paper. University of Rochester.

Grossbard-Shechtman, Amyra. 1984. A theory of allocation of time in markets for labour and marriage. Economic Journal 94(376):863–882.

Grossbard-Shechtman, Shoshana A. & Shoshana Neuman. 1988. Women's labor supply and marital choice. Journal of Political Economy 96(6):1294–1302.

Hamer, Dean & Peter Copeland. 1998. Living with our genes. Doubleday Books, New York.

Hammermesh, Daniel S. & Jeff E. Biddle. 1994. Beauty and the labor market. American Economic Review 84(5):1174–94.

Hendricks, Lutz. 2000. Do taxes affect human capital? The role of intergenerational persistence. Working paper. Arizona State University.

Hirshleifer, Jack. 1987. On the emotions as guarantors of threats and promises. Pp. 307–326 in J. Dupre (ed.) The Latest on the Best: Essays on Evolution and Optimality. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Johnston, Victor S. & Melissa Franklin. 1993. Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Ethology & Sociobiology 14(3):183–199.

Kauffman, Stuart. 1995. At home in the universe: the search for laws of self-organization and complexity. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Keyfitz, Nathan (ed.) 1984. Population and biology. Ordina Editions, Liege, Belgium.

Lam, David. 1988. Marriage markets and assortative mating with household public goods: theoretical results and empirical implications. Journal of Human Resources 23:462–87.

Lamarck, J.B.P.A. de Monet. 1809/1963. Zoological philosophy: an exposition with regard to the natural history of animals. H. Elliot, trans. Hafner, New York.

Leslie, P. H. 1945. On the use of matrices in certain population mathematics. Biometrika 33:183–212.

Little, Michael A. & Jere D. Haas (ed.) 1989. Human population biology: a transdisciplinary science. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Lucas, Robert E. Jr. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22:1–42.

Lucas, Robert E. Jr. 1993. Making a miracle. Econometrica 61(2):251–72.

Lundberg, Shelly & Robert A. Pollak. 1996. Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives 10(4):139–158.

Lundberg, Shelly & Robert A. Pollak. 1993. Separate spheres: bargaining and the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy 101(6):988–1010.

McClearn, Gerald E., Boo Johansson & Stig Berg. 1997. Substantial genetic influence on cognitive abilities in twins 80 or more years old. Science 276:1560–1563.

Miller, Geoffrey F. 2000. The mating mind: how sexual choice shaped the evolution of human nature. Anchor Books/Doubleday, New York.

Mueller, William H. 1976. Parent-child correlations for stature and weight among school-aged children: a review of 24 studies. Human Biology 48(2):379–397.

Mulligan, Casey B. 1997. Parental priorities and economic inequality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Park, Kwang Woo & Paul J. Zak. 2001. Population genetics, unstable households, and economic growth. Working paper, Claremont Graduate University.

Perotti, Roberto. 1996. Growth, income distribution, and democracy: what the data say. Journal of Economic Growth 1:149–187.

Plomin, Robert. 1994. Genetics and experience: the interplay between nature and nurture. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Plomin, Robert & C.S. Bergeman. 1991. The nature of nurture: genetic influence on ‘environmental’ measures. Behavior and Brain Science 14(3):373–427.

Plomin, Robert & Stephen A. Petrill. 1997. Genetics and intelligence: what's new? Intelligence 24(1):53–77.

Plomin, Robert, John C. DeFries, Gerald E. McClearn & Peter McGuffin. 2000. Behavioral genetics, 4th ed. W.H. Freeman, New York.

Purtilo, David T. Christine K. Cassel, James P. Yang & R. Harper. 1975. X-linked recessive progressive combined variable immunodeficiency (Duncan's disease). Lancet 1(1793):935–940.

Qureshi, Salman T., Emil Skamene & Danielle Malo. 1999. Comparative genomics and host resistance against infectious diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases 5(1):36–47.

Regan, Pamela C. & Ellen Berscheid. 1997. Gender differences in characteristics desired in a potential sexual and marriage partner. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality 9(1):25–37.

Regalia, Ferdinando & Jose-Victor Rios-Rull. 1999. What accounts for the increase in single households and the stability in fertility. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Romer, Paul. 1986. Increasing returns and long run growth. Journal of Political Economy 94(5):1002–1037.

Romer, Paul. 1990. Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy 98(5):71–102.

Rubinstein, Yoram & Daniel Tsiddon. 1999. Coping with Technological progress: the role of ability in making inequality so persistent. CEPR Discussion Paper #2153.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1956. Social indifference curve. Quarterly Journal of Economics 70(1):1–22.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1958. An exact consumption-loan model of interest with or without the social contrivance of money. Journal of Political Economy 66:467–482.

Seger, Jon & Robert Trivers. 1986. Asymmetry in the evolution of female mating preferences. Nature 319:771–773.

Seitz, Shannon N. 2000. Employment and the sex ratio in a two-sided model of marriage. Working paper, University of Western Ontario.

Simon, Herbert A. 1997. Models of bounded rationality: empirically grounded economic reason. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Singer, Irving 1984. The nature of love. v.3. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Singer, Irving 1994. The pursuit of love. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Solomon, Robert C. 2001. About love. Madison Books, Lanham MD.

Stokey, Nancy. 1996. Free frade, factor returns, and factor accumulation. Journal of Economic Growth 1:421–447.

Strickberger, Monroe W. 1985. Genetics 3rd Edition. Macmillan, New York.

Takahata, Naoyuki & Andrew G. Clark. (ed.) 1993. Mechanisms of molecular evolution. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo.

Trivers, Robert. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. Pp. 136–179 in Bernard Campbell (ed.) Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, Aldine-Atherton, Chicago.

Tamura, Robert. 1996. From decay to growth: a demographic transition to economic growth. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 20:1237–1261.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1998. Current population reports. December.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1999. Statistical abstract of the United States.

Weiss, Yoram. 1997. The formation and dissolution of families: why marry? Who marries whom? And what happens upon marriage and divorce. Pp. 81–123 in Mark R. Rosenzweig and Oded Stark (ed.) Handbook of Population and Family Economics, North-Holland Publishers, New York.

Weiss, Mark L. & Alan E. Mann. 1985. Human biology and behavior. 4th ed. Little, Brown and Co, Boston.

Weitzman, Martin L. 1998. Recombinant growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(2):331–360.

Westermarck, Edvard A. 1891/1997. The history of human marriage. Omnigraphics, Detroit.

Wills, Christopher. 1998. Children of Prometheus: the accelerating pace of human evolution. Perseus Books, Reading.

Wilson, Edward O. 1984. Conversation with Richard C. Lewontin at the Harvard University Conference on Biology and Demography, February 9–11, 1981, reported on p. 17 in Nathan Keyfitz (ed.) Population and Biology. Ordina Editions, Belgium.

Wilson, Edward O. 1998. Consilience: the unity of knowledge. Vintage Books, New York.

Wolf, Arthur P. 1995. Sexual attraction and childhood association: a Chinese brief for Edvard Westermarck. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Zak, Paul J. & Arthur Denzau. 2001. Economics is an evolutionary science. Pp. 31–65 in A. Somit and S. A. Peterson (ed.) Evolutionary Approaches in the Behavioral Sciences: Toward a Better Understanding of Human Nature. JAI Press, New York.

Zak, Paul J. & Stephen Knack. 2001. Trust and growth. The Economic Journal 111:295–321.

Zak, Paul J., Yi Feng & Jacek Kugler. 2002. Immigration, fertility, and growth. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 26:547–576.

Zak, Paul J. 2002. Genetics, family structure, and economic growth. Journal of Evolutionary, forthcoming.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zak, P.J., Park, K.W. Population Genetics and Economic Growth. Journal of Bioeconomics 4, 1–38 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020604724888

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020604724888