1 Introduction

Reconstructing the spoken language of the past has been of perennial interest to English historical linguists and scholars of related fields (see e.g. Culpeper & Kytö Reference Culpeper and Kytö2010; Schneider Reference Schneider, Chambers and Schilling2013). Whether the focus is on phonology, morphology, syntax, or some other aspect of the language, this pursuit of historical speech has involved negotiating the well-known problem of having recourse to written sources only (until the early twentieth century or so). As has been pointed out in present-day research on speech representation (e.g. Vandelanotte Reference Vandelanotte2009: 118–30), the written language cannot fully and straightforwardly capture the spoken language. Inevitably, then, the reconstruction is also – or should also be – concerned with the mechanisms and dynamics of the representation itself. That is, we cannot hope to understand what the representation of speech entails without understanding the linguistic tools that language users employ to represent speech in writing and the varying functions and implications of the choices at the users’ disposal. These mechanisms cannot simply be dismissed or peeled away to reveal the essence of the spoken language; rather they have to be analyzed, described and theorized as a vital part of reconstructing the spoken language of the past. While there is a growing body of research concerned with these features in the history of English, much remains unknown about historical-synchronic and diachronic aspects of speech representation (for an overview, see Grund & Walker Reference Grund and Walker2020b).

In this article, I explore one aspect of this mediation of speech: how language users integrate evaluation of the speech they represent in the representation of the speech itself. Specifically, I explore how speech reporters (whether witnesses, the scribes taking down the records, court officials or others) evaluate, frame and position the speech that they represent in the court records in the Old Bailey Corpus, which covers the late Early Modern English and especially the Late Modern English periods (1720–1913). In this article (as part of a broader interest and project), I investigate speech descriptors (Grund Reference Grund2017, Reference Grund2018), which are metalinguistic features of the kind seen in (1) and (2).

(1) It was said exultingly (t18210411-64)Footnote 2

(2) he used most disgusting language (t18460706-1443)

Here exultingly and most disgusting add the speech reporters’ evaluation of the delivery or the nature of the original speaker's language. The type illustrated in (2) is the focus of my analysis, where the lemma language refers to a previous speech event, and the adjective or adjective phrase (most disgusting) supplies an evaluative component to the speech representation.

So far, as regards mechanisms and functions, speech representation in Late Modern English has primarily been studied in literary works, while other genres remain understudied (see section 2). This article begins to fill that generic gap, and it complements the angles taken in other contributions to this special issue, which focus not on the mechanisms of representation (that is, the features used to signal, frame or convey language as spoken) but on how the spoken language can be traced in written representations. My discussion also provides scholarly attention to pragmatic and discoursal features of Late Modern English, which remain relatively unexplored (Lewis Reference Lewis, Bergs and Brinton2012: 911).

In section 2, I provide a background to the study of speech representation in the history of English and of speech descriptors in particular. Section 3 is devoted to the material (the Old Bailey Corpus) and the methodology of the article. Section 4 covers the overall quantitative patterns of the data as well as more qualitative analyses of examples and contexts. I pay special attention to the sociopragmatic goals of language users in deploying speech descriptors in their representation of other people's speech. I summarize and discuss the broader significance of the results in section 5.

2 Background

Research into speech representation in the history of English has focused on a number of overlapping topics, including the mechanisms used to mark language as reported speech (speech reporting verbs, quotation marks, etc.), the categories of speech representation (direct speech, indirect speech, free indirect speech, etc.), and the functions of speech representation for users in various contexts and genres (see Grund & Walker Reference Grund and Walker2020a; Grund Reference Grund and Bealforthcoming). In all of these different areas, we see continuity, variation and change in the history of English. As Moore (Reference Moore2011, Reference Moore2020) and Vandelanotte (Reference Vandelanotte2020), among others, have shown, our convention of using quotation marks to signal direct speech is a much-negotiated development, and we do not see the convention firming up until well into the nineteenth century. Speech reporting verbs (such as say, answer, retort) show a variety of developmental trends: while some verbs more or less disappear over time (such as queþan/quethen, most commonly found in the forms quoth and quod), the overall number increases across the history of English, new members being added especially in the Early and Late Modern English periods, including the quotative be like (e.g. D'Arcy Reference D'Arcy2017; Cichosz Reference Cichosz2019; Walker & Grund Reference Walker and Grund2020a). Throughout the history of English, redeploying speech has frequently (always?) involved more than simply repeating in writing (or conversation) what someone has said; rather, speakers ‘revoice’ the language or ‘reanimate’ the voices for specific social and pragmatic purposes (see Collins Reference Collins2001). Scholarship on genres ranging from early news writing to letters and witness depositions has outlined functions such as adding credibility and authority to speakers and speech reporters, foregrounding and backgrounding of voices and speakers, as well as delineating voices and structuring reported speech (e.g. McIntyre & Walker Reference McIntyre and Walker2011; Evans Reference Evans2017, Reference Evans2020; Walker & Grund Reference Walker and Grund2017).

Aspects of speech representation have been studied for all periods, but we lack a clear overarching narrative of change and stability over time and a picture of the usage within specific periods. In Late Modern English – the focus of this article and this special issue – attention has mainly been paid to literary texts. This is to some extent understandable. Major developments appear to have taken place in this period in the representation of voices and speakers in fiction, especially as part of the development of the novel in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Notably, these developments include the adoption and solidification of so-called ‘free indirect speech’ as a separate speech representation mode (e.g. Lambert Reference Lambert1981; Page Reference Page1988; Sotirova Reference Sotirova, Hoover and Lattig2007; Busse Reference Busse2020; Grund Reference Grund, Kytö and Smitterberg2020a,Reference Grundb; Vandelanotte Reference Vandelanotte2020). Newspaper writing and letters have also been studied to some extent (e.g. Jucker & Berger Reference Jucker and Berger2014; Nevala & Palander-Collin Reference Nevala, Palander-Collin, Tanskanen, Helasvuo, Johansson and Raitaniemi2010; Palander-Collin & Nevala Reference Palander-Collin, Nevala, Pahta, Nevala and Nurmi2010), but, to my knowledge, other genres remain unexplored, including legal records, as discussed in this article.

As evidenced also by other contributions to this special issue, the reconstruction of Late Modern spoken English is attracting increasing interest, including aspects of regional and social dialect (e.g. Cooper Reference Cooper2023; Gardner Reference Gardner2023; Hodson Reference Hodson and Hodson2017, Reference Hodson2023; Ruano-García Reference Ruano-García2023), and phonological variation and developments (e.g. Beal, Sen, Yáñez-Bouza & Wallis Reference Beal, Ranjan, Yáñez-Bouza and Wallis2020; Beal Reference Beal2023; Wiemann Reference Wiemann2023). The Old Bailey Corpus, which provides the data for my investigation, has been a popular source for research of Late Modern English speech, in large part because of the assumed proximity of the court materials to the actual voices of speakers from all walks of life, including people of the lower social classes (see Huber Reference Huber2007). These studies have explored a variety of speech-related, sociolinguistic and interactional features in Early and Late Modern English (e.g. Traugott Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011, Reference Traugott2015; Archer Reference Archer2014; Säily Reference Säily2016; Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016, Reference Huber2017; Claridge Reference Claridge2020; Claridge, Jonsson & Kytö Reference Claridge, Jonsson and Kytö2020a,Reference Claridge, Jonsson and Kytöb; see section 3).

In this article, I take an approach to speech representation in Late Modern English that extends beyond current approaches and areas of concentration. I focus on a fairly neglected feature of speech representation in general – speech descriptors – and their functions and implications for how we understand speech representation dynamics in this period. These descriptive and evaluative features are mostly mentioned only in passing in secondary literature (e.g. Caldas-Coulthard Reference Caldas-Coulthard and Coulthard1987: 165–6; Brown Reference Brown1990: ch. 6; Oostdijk Reference Oostdijk1990: 239; de Haan Reference de Haan1996: 36–7; Urban & Ruppenhoffer Reference Urban and Ruppenhofer2001: 84–5; Ruano San Segundo Reference Ruano San Segundo2016: 117; Eberhardt Reference Eberhardt2017: 239–41; cf. also Lippman & Tragesser Reference Lippman and Tragesser2005). In their exploration of swear words and taboo language in the OBC, Widlitzki & Huber (Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016: 320) refer to disgusting language as a ‘metalinguistic comment’ on reported language, but do not pursue the significance of these types of comments.

The lack of focused scholarly attention to speech descriptors does not accurately reflect the important work they perform in speech representation. Indeed, they are not infrequent and have various social and pragmatic functions (Grund Reference Grund2017, Reference Grund2018, Reference Grund, Kytö and Smitterberg2020a,Reference Grundb). Examples (3) and (4) provide illustrations of prototypical speech descriptors.

(3) she said faintly, yes, I have got it (t17920113-24)

(4) He refused to satisfy us, but damn'd us, and gave us very opprobious Language (t17350116-6)

As shown in (3) and (4), speech descriptors come in different forms, but they are usually adjective, adverb or prepositional phrases attached to or modifying a noun, verb or other structure that signals the reporting of a speech event. Faintly in (3) gives an indication of how the speech reporter assesses the speech to have been delivered. In (4), very opprobrious signals more of an evaluation about the nature or intent of the language used by the original speaker. Importantly, speech descriptors give us access to more intangible aspects of the speech that are otherwise difficult or impossible to convey in writing (and to some extent in speech), including aspects of the (perceived) social and pragmatic characteristics of the representation.

3 Material and methodology

My data comes from the Old Bailey Corpus 2.0 (OBC), drawn from the larger source of Old Bailey Online: The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674–1913, available at www.oldbaileyonline.org. The corpus covers 637 of the proceedings from the Old Bailey Court (later renamed the Central Criminal Court) in London; it amounts to 24.4 million of what the compilers consider ‘spoken’ words from the end of the Early Modern English period and especially the Late Modern English period, 1720–1913 (Huber, Nissel & Puga Reference Huber, Nissel and Puga2016a).Footnote 3 Most of my data is not surprisingly from the nineteenth century, as the proceedings are particularly plentiful from that period (Huber, Nissel & Puga Reference Huber, Nissel and Puga2016b: 5–7).

The records (and hence the corpus) present a complex textual product. They include various kinds of legal records as part of the regular trial process at the time, such as indictments, witness testimonies and defense statements. However, the proceedings do not provide complete records of the trials. At certain points, aspects of the trials were ‘routinely omitted’ from the published records, including opening statements, legal arguments, discussions among legal counsel and the presiding judge, and summations by judges (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2008: 571–2; Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. a). The ways the trials were conducted changed over time as did the way the records were produced and published. The corpus is based on contemporaneous commercial publications of the court proceedings stemming from notes taken down by one or more short-hand writers present at the time. Especially in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, these publications were sensationalist, aiming to cover only the most salacious trials and only the parts that were deemed interesting to a broad public. That approach changes over time so that the proceedings become more comprehensive in terms of the trials covered and more formal in tone, especially after the 1780s, but even then not all the aspects of the trial proceedings were necessarily recorded (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2008; Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. b). Of the various materials, the testimonies are the most important for this study, as the speech representation and evaluation mostly (though not exclusively) occur in witness statements.

Despite these complex publication issues, the proceedings and hence the OBC have been claimed to be as close as we can get to the spoken language of the time (e.g. Huber Reference Huber2007; Archer Reference Archer2014; Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016). For my purposes, whether the language accurately represents the original speech is less important; I focus on how the reporters take charge of the language they represent and evaluate and frame it in various ways.

As noted in section 1, I explore how speech descriptors occur with the lemma language. I chose this particular lemma as my previous studies of court language in Early Modern English have shown it to be a site of negotiation and evaluation of speech (e.g. Grund Reference Grund2017). I searched the corpus using the CQPWeb interface (http://corpora.clarin-d.uni-saarland.de/cqpweb/) with a ‘Word lookup’ search of ‘language*’ (capturing both language and languages; no spelling variations were detected). This search resulted in 948 instances of language. Of these instances, some pertain to written language and are obviously not relevant for my focus here on the representation of spoken language. Of those instances that refer to spoken language, we see three basic patterns, only one of which is relevant for this study. Examples such as (5) and (6) are not included in this study: (5) includes no modification or evaluation, and (6) uses a descriptor of language variety. Although this use can be seen as a speech descriptor (see e.g. Grund Reference Grund2020b: 122), I do not consider it here, as I focus on the sociopragmatic evaluation.

(5) Barwell, when he heard this language, shook his head (t17970920-31)

(6) I looked upon it, and said to my Son in the Hebrew Language, I am afraid that Watch is not honestly come by (t17431207-24)

With these exclusions, the dataset consists of 521 instances of language with an evaluative marker indicating the nature or character of the speech. At 17.25 instances per million words, this is overall a low-frequency feature. But as we shall see, it is an important tool for some speech reporters as they negotiate their roles in the trials and present their evidence. Examples are provided in (7)–(11).

(7) The prisoner felt himself agrieved, and made use of very bad language (t18161204-93)

(8) Mrs. Avery depos'd, That in the Pastry-Cook's Shop the Deceased gave the Prisoner very insulting language (undefined in the OBC)

(9) she called him names, and used shameful language about his sleeping with his sister (t18320705-108)

(10) Williams came up and spoke to me three times in indecent language (t18991120-24)

(11) she became violent, and used violent and obscene language (t18950722-563)

Most examples represent what Semino & Short (Reference Semino and Short2004: 43–5, 52–3) would term ‘narrator's representation of voice’ (NV) or ‘narrator's representation of speech acts’ (NRSA). These types involve minimal representation of the previous speech itself, simply indicating that speech took place (NV) or that speech amounting to a particular speech act occurred (NRSA). In (7), we see an NV example where we simply get a sense that ‘the prisoner’ said something and that the reporter evaluates it as bad, but not what the actual formulation or content was. In (8), on the other hand, the designation of the language as insulting suggests that the speech expressed the speech act of insult (at least in the speech reporter's estimation). The exact cutoff point for the two types is not always clear, however. In (9), we see more detail about what was said (according to the reporter), and the representation could be seen as pointing to the speech act of a claim, statement or assertion, but it is short on detail.

The evaluation of language may not be the focus of the actual representation; in some cases, illustrated in (10), the descriptor + language occurs in a prepositional phrase that modifies another speech representation expression. Here the prepositional phrase as a whole functions as a speech descriptor for spoke. These structural differences are not considered further in this article.

Finally, there are nineteen instances of multiply-modified instances of language, as in (11). In these cases, I count each of the descriptors separately, which means that the total dataset considered is 541 instances.

4 Results

4.1 Quantitative overview

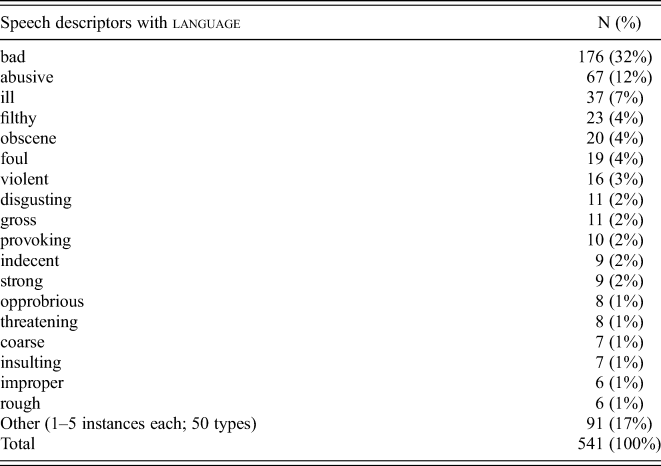

Table 1 gives an overview of the results of the study. A few results stand out from the table. The speech description is dominated by a few adjectives, most notably bad and abusive. There are some adjectives with middling frequencies (from filthy and obscene to improper and rough), and then a large number of adjectives with low frequencies, especially with a single instance (such as affronting, civil, quarrelsome, ugly). This kind of distribution is not unusual in linguistic studies and indicates the kind of A-curve that Kretzschmar (Reference Kretzschmar2010: 276–9) has theorized in language variation and change. The top adjectives are all negative in nature; in fact, about 98 percent of the adjective instances are negative. For criminal court records, it is not unexpected that there should be a focus on negative evaluation, but the predominance is notable (yet explainable, as we see below).

Table 1. Speech descriptors with language

The use of speech descriptor+language increases over time, as seen in table 2. The table excludes thirty examples that are given as ‘undefined’ in terms of period and other information in the OBC.

Table 2. Diachronic pattern of speech descriptor+language

There is an overall increase between the eighteenth and the following centuries (nineteenth and twentieth). A breakdown of the data according to decade shows a great deal of fluctuation across decades (table 3). These fluctuations require more detailed study than is possible here. While there is no clearly linear development, we see an overall difference between the period up to and including the 1830s and the 1840s and after. The average normalized frequency for the former period is 9.57 and for the latter 26.17.

Table 3. Decade breakdown

It is not clear how to interpret this diachronic trend. Part of the reason may lie in the nature of the OBC materials. As we saw in section 3, the proceedings from the Old Bailey were not uniformly recorded over time, and the differing publication circumstances may affect temporal patterns. McEnery (Reference McEnery2006: 99–100) has pointed to the impact of a developing standard of language ‘purity’ in the eighteenth century, tied closely to morality and pushed by a number of religious societies in particular (see also Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016: 321–2). This push seems to have had a long-term effect. One such effect may be reflected in the temporal trend in speech descriptor+language, where reporters stay away from repeating ‘impure’ language, and instead focus on the description of the language and hence their stance towards the language and the speaker (see section 4.3.3).

Why there should be a dividing line in the 1830s and 1840s on this score is unclear, and the reason for the change may lie elsewhere. The court and the publication of the proceedings did see some changes at this approximate time. Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker (Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. b) note that ‘[t]he Central Criminal Court Act of 1834 changed the name of the court and enlarged its jurisdiction’, and that ‘the Proceedings were now essentially a publicly funded publication for the use of judicial officials’. However, I have not been able to trace convincingly a connection between this shift and the use of speech descriptor+language.

There may also be larger linguistic dynamics at play. Other related speech representation choices may impact overall patterns of speech descriptor+language, including closely aligned choices such as speech descriptor+word or speech descriptor+expression, as in (12) and (13). Possible interchangeability among these expressions (and/or others) could thus affect the result (see Grund Reference Grund2020b).

(12) he swore and made use of bad expressions (t17770910-19)

(13) Buckingham said that the defendant used abusive words to him (t18961214-91)

Trends for individual speech descriptors are difficult to discern, especially since most of them do not occur in large numbers. The two most common speech descriptors, bad and abusive, occur across the centuries, and both are represented in all decades. At the same time, their representation in the speech descriptor+language context differs. Abusive represents 14% of the examples in the eighteenth century, 13% in the nineteenth and 9% in the twentieth, while bad mirrors (and probably substantially influences) the general increase and leveling shown in the overall distribution in table 2: 15%, 36% and 37%. This increasing dominance of bad in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is not directly correlated with a straightforward decrease of types in those centuries, as we see 25 types in the eighteenth century, 52 types in the nineteenth and 12 types in the twentieth. In the twentieth century, there is a clear preference for bad, with just a sprinkling of other types. The relatively small size of the corpus in this century (c. 2.5m words) may be a factor in these results.

In terms of other adjectives, many types are only or predominantly found in the nineteenth century, again perhaps partly because of the larger size of this part of the corpus (c. 16.9m words), including threatening, violent, foul and improper (a breakdown according to decade is mostly unhelpful here since there are overall few instances). Two words show trends that cannot be accounted for by corpus size, however. Ill represents 24 out of 91 instances (or 26%) in the eighteenth century, 11 out of 365 (or 3%) in the nineteenth (and none after the 1850s) and 0 instances in the twentieth. Part of this drop may be correlated with the rise of bad. It is not always clear what ill language means (see e.g. example (15) below); the OED (s.v. ill) records a number of related meanings, from ‘evil’ and ‘depraved’ to ‘malicious’ and ‘hurtful’. Frequently it seems to mean something ‘bad’ in general in the OBC records and may thus be increasingly replaced by bad over time. This development may also, of course, be related to broader changes in the semantics of ill, where, perhaps, the predominant meaning shifted over time to be more closely associated with a person's health condition.

Obscene is only used once in the eighteenth century, 9 times (or 2%) in the nineteenth (7 of 9 examples in the 1880s and 1890s), but represents 19% in the twentieth century (or 10 instances). It is not clear what is behind this trend. Larger language trends and preferences may of course be behind this and other choices. These adjectives are not always (or perhaps never) exactly in variation in the sense that language users choose one or the other to express the same thing. The variation and change may thus simply be attributable to speech reporters (or others) evaluating slightly different aspects of the content of the speech or the verbal behavior, or expressing slightly different evaluations over time (see also the discussion of recorders in section 4.3.2.).

4.2 Qualitative groupings

From a qualitative perspective, a few, partly overlapping, semantic-functional groupings of speech descriptors emerge. The most prominent group involves evaluations that focus on the inherent value or nature of the represented language (in the speech reporter's estimation). Here we find adjectives such as bad, coarse, dirty, gross, ill, indecent, vile, vulgar and filthy, illustrated in (14) and (15).

(14) he used very filthy language (t18990912-611)

(15) on Monday the 16th of May, between 11 and 12 at Night, he, with his Father was going home, when over against Suffolk-street they met with Mr. Clifton; who gave them very ill Language, which his Father could not take (undefined in the OBC)

Although these evaluations ostensibly focus on the language itself, there are often hints, and sometimes not so subtle ones, that these evaluations also apply to the original speaker. That is, it is not only the language that is filthy or coarse, but, by extension, also the original speaker (see section 4.3.3).

The second group of evaluative adjectives overlaps in some ways with the first. However, in this category, the usage is more explicitly concerned with evaluating how the language reflects on or relates to the original speaker, as in the use of blackguard, civil, uncivil, disgraceful, scurrilous, unbecoming and shameful in (16) and (17).

(16) he then used most shameful language – I told him it was not fit language to use in female company (t18410920-2512)

(17) the woman was using unbecoming language (t18520614-626)

The way the language is evaluated as reflecting speaker characteristics varies: some speech reporters concentrate on perceived correlations between the speech and criminal behavior, whereas others appear more related to social mores or gender constructions. Both (16) and (17) hint at gender expectations in the nineteenth century, but from slightly different angles. The reporter in (16) suggests that the original speaker broke conventions regarding appropriate language around women. Example (17), on the other hand, points to inappropriate language used by a woman (according to the reporter), suggesting clear gender-related language standards: this is not language that is unbecoming for anyone, man or woman – if so, that would presumably have been clarified by a more explicit evaluative term, such as filthy or abusive. Instead, the choice of unbecoming in the context of reporting the woman's language was clearly seen as significant and weighty to give a sense of the social impropriety of the language and the damning nature of it. As McEnery (Reference McEnery2006: 199) notes, in the nineteenth century, from which both examples derive, women were seen as ‘guardians of the nation's morality’, and ‘immodest behaviour such as using bad language became the negation of womanhood’.

While different from the first two categories, the final two groups also overlap. Though not very common in terms of types, the group that focuses on the effect of the language on a hearer or the target of the language has some frequent adjective members, especially abusive, but also offensive and shocking, as in (18) and (19).

(18) he followed me and behaved in a very indecent manner, and made use of very abusive language, pulling me by the arm, and said he would not leave me till he had something from me; he made use of very abusive language, calling me b—r, and those names (t17921031-33)

(19) She made use of shocking language in the coach, both to me and my wife that at last I said she should not come to my place again. (undefined in the OBC)

In examples of this kind, speech reporters often appear to put themselves at the center of the language negotiation rather than focus on the inherent nature of the language. In (18), the language was abusive (or insulting) to the speech reporter and target of the language; in (19), on the other hand, the reporter (and again target) of the represented language stresses the reaction or effect of the language on the reporter and his wife, hinting at the breach of social decorum.

Similar dynamics are evident in the final group, where speech descriptors specify the language as belonging to particular speech acts. These speech acts affect a hearer or target, and are, not surprisingly, inherently negative in the sense that they are connected with verbal behavior that is deemed transgressive in terms of social norms. Here we find examples such as threatening, provoking, affronting, insulting and taunting, as in (20) and (21).

(20) he used other taunting language in the street (t18300218-73)

(21) I stood there two or three minutes, while he was making use of the most awful and threatening language – he said if I called anybody to my assistance, he would serve them as he did me – (t18481218-357)

In (21), we get at least a partial sense of what it is that the speech reporter considers threatening, while (20) provides no context for the evaluation of taunting (see section 4.3.1).

Overall, the descriptors are concerned with various overlapping aspects of the original speech. They put the spotlight on the words, the original speaker and/or the hearer or target of the language.

4.3 The sociopragmatics of speech descriptor+language

4.3.1 What is evaluated?

A central aspect of the use of speech descriptor+language in the OBC is that the original language to which the construction refers is not usually available in the record. That is, it is mostly impossible to see exactly what the speech reporter interpreted and evaluated as gross, abusive, insulting and the like. We do see some glimpses in some records, as in (22).

(22) the prisoner had used threatening language to him – I think it was, “I will give you something to quiet you,” (t18680504-480)

Here the speech reporter gives the representation as direct speech (indicated in the printed version of the record with quotation marks), which suggests that the record is somehow faithful to what was originally said. However, the reliability of the record can often be questioned, for a variety of reasons (section 4.3.2). In (22), the speech reporter even hedges the representation with I think, leaving open the degree of accuracy of the representation.

In some cases, the representation structure in the record renders it ambiguous whether a particular string of representation is the object of the evaluation expressed in speech descriptor+language. Examples (23) and (24), which come from different witness statements from the same trial, are illustrative cases.

(23) then the prisoner came to the kitchen with his barrow – the deceased was there, she used bad language to him, she called him a f—g ponce. (t18980913-640)

(24) afterwards Alice Loft-House came in — she made use of bad language — she said, “You dirty ponce” (t18980913-640)

Both witnesses evaluate some language usage as bad, and they follow up with more specifics about what was said. It seems reasonable to assume that the name calling and verbal abuse here represents the ‘bad language’,Footnote 4 but it could also be that the bad language refers to something else or some additional language not specified; that is, she used bad language and she made use of the language reported more explicitly. The language reported in the two examples is also not the same. This may partly be because of the different reporting structures used. Example (24) is reported in direct speech, with quotation marks and direct address (you), while (23) can be interpreted in different ways, as an indirect speech structure with fucking directly quoted or perhaps even as a type of free indirect speech.Footnote 5

The records often ‘bleep’ out words that were seen as particularly offensive or unacceptable with the help of hyphens and dashes, as seen in (23). This is a common strategy for taboo words in the OBC (Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016: 316–17). The convention may seem surprising considering the fact that the Old Bailey Proceedings represent legal records where accurately recording what the speech reporter said would seem to be paramount. In this context, it is important to remember that the Old Bailey Proceedings were also commercial products, intended for a broad audience. Authorities tried to strike a balance where the ‘trial accounts should not be presented in such detail that either morals were corrupted or judicial authority was jeopardized’ (Devereaux Reference Devereaux1996: 491). It is thus tempting to see speech descriptor+language formulations as another device of suppressing actual offensive language but at the same time retaining some of the detail needed to reflect content that was legally necessary (see section 4.3.3).

However the words are treated in the speech representation, it is unclear whether this language represents what the original speaker said, since it is filtered through witnesses, the court recorders, court officials and the publisher of the proceedings (cf. Walker & Grund Reference Walker and Grund2017; see section 4.3.2). The upshot is that most of the time we cannot tell what it is that the reporter considers bad, abusive, shocking or threatening. The lack of reliable access to the original speech is perhaps disappointing and slightly surprising, as we would expect the language to be central in the trials. However, as I argue in section 4.3.3, there are several reasons why we see these patterns, and exploring those reasons will give us some purchase on the kind of social and pragmatic functions that these speech representation structures and evaluations had.

For the most part, judging by the contexts of speech descriptor+language, this reporting structure and evaluation was acceptable to the court, unless substantial portions of language negotiations have been left out of the published records (see section 4.3.2). The acceptability perhaps partly stems from the fact that the language is never the central point of the case. Defamation cases, for example, were never heard at the Old Bailey, but would have been handled in other court systems. The Old Bailey did have purview over written libel (Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. c), but since speech representation is not involved there, such cases are not relevant here. ‘Seditious words’ (that is, ‘[s]peaking scandalous, seditious, and traitorous words against the King’) were prosecuted at the Old Bailey, but no examples of this type appear to be part of my dataset (Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. c).

On rare occasions there are follow-ups from a court official that lead to specification. The example in (25) illustrates such a case, where the witness, Roberts, notes the use of ill language but is questioned (‘Q’) about its nature, and he provides further, though not exact, detail.

(25) and there were some ill language given to them.

Q. What about ?

Roberts.

About spitting in their faces, such words were mentioned, and shitting in their mouths very indecent expressions. (t17611021-30)

Notably, the court (presumably the judge or judges) does not ask for specifications of exactly what was said but a specification of content. The witness gives a paraphrase, but a graphic one focusing on particular words reflecting the ‘ill’ nature of the language. This focus on content is in keeping with what previous studies have shown about the focus on substance and lexical content rather than exact formulations in speech representation in historical legal contexts (see section 4.3.2).

4.3.2 Who is the evaluator?

The instances of speech descriptor+language are predominantly found in statements from witnesses and victims: 463 of the 541 instances occur in their statements.Footnote 6 Since these instances predominate, I discuss them in particular detail in section 4.3.3, as I analyze the purpose of the evaluation. Here I focus on the less common speaker roles and broader considerations of how to gauge who the evaluator is.

In addition to victim and witness statements, we also find instances in statements from defendants, judges and lawyers.Footnote 7 Evaluative remarks by judges (six instances) and lawyers (eleven instances) are infrequent, but they do occur in contexts such as those represented in (26)–(28).

(26) Here's a Parcel of Whores and Bands that will swear any thing against me.

Court.

If you have any thing to say in your Defence the Court will hear you, but you must not be suffer'd to give such abusive language. (t17330628-7)

(27) she hit him a Slap o’ th’ Face, and spit in his Face, and pull'd him by the Breeches, and said, You Son of a Bitch, you want to go to your Whores, do you?

And at 11 a Clock I left ’em good Friends.

Court.

Tho’ she had spit in his Face, and given him such gross language! (t17330912-56)

(28) Mr. Oliver was talking with Mrs. Young at the bar; the watchman came, the prisoner did not say any thing that I heard; I picked up the pocket-book under the tap-room table, about a yard and a half from the prisoner.

Q. Did any abusive language pass?

A. Not to my knowledge. (t18000528-128)

In (26), the ‘court’ responds to actual language used in the court room, turning against the verbal abuse that a defendant levels against witnesses in her case, and calling on the defendant to limit herself to appropriate language. Example (27), on the other hand, suggests that the court is skeptical about the report provided by the witness, either regarding the language represented or regarding the account that the witness provides (how could the husband and wife be so quickly reconciled after the woman's verbal and physical abuse?). Finally, example (28) represents the court's framing of language in a particular way, perhaps drawing on earlier evaluation provided by another witness in the case.

Defendants also make use of speech descriptor+language (twenty-seven instances). Most of the instances concern language that the defendants attribute to others. But they also address their own language, usually in the negative, as in (29).

(29) I have never pleaded being drunk.

I was not using obscene language.

It was an elderly man who was drunk was using obscene language when Stevens came up.

He was swearing at me and I swore back. (t19060430-64)

Example (29) comes from a cross-examination of a defendant. Here the defendant may be pushing back against a number of claims or accusations from others. The string of negated statements (only a couple of which are cited here) may also have been triggered by specific cross-examination questions that are not explicitly given here. If that is the case, the framing of some alleged language as obscene was possibly that of the examiner (whether a lawyer or a judge). These negated statements are not only found in defendant statements, but also occur when witnesses push back against other witness statements or when they make clear that they did not hear verbal behavior that has been ascribed to an accused (see section 4.3.3).

As is obvious from these examples, we see representation from many different parties in the trial process. But there are yet more complex issues involved in the evaluation provided in speech descriptor+language sequences that pertain to the production and the textual state of the OBC material. The records from the Old Bailey were taken down by scribes in short-hand (at least from 1749, but probably earlier; Huber Reference Huber2007: 3.2.2; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2008: 563). The transcripts they produced (possibly after expansion from short-hand and editing) were handed over to a printer and associated staff for publication (Huber Reference Huber2007: 3.2.1). The details of this process are not known, including what procedures were used during typesetting and possible proofreading (Traugott Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011: 72), and they changed somewhat over time, for example, with the Criminal Appeal Act of 1907 when ‘taking of full shorthand notes of trials … became a statutory requirement, with the appointment of the shorthand writer made by the Lord Chancellor, and their fees paid by the Treasury’ (Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. b).

In a complex situation of textual production and transmission, the question is whether some of the speech descriptor+language examples are provided by the recorder or at least whether the choice of the particular speech descriptor deployed was that of the recorder. We know from other contexts that language provided in historical court documents rarely represents the type of verbatim recording that we expect from present-day court records.Footnote 8 Often, even when a string of represented speech is given as direct speech (with features resembling actual spoken language), what we get is a court-sanctioned representation of speech based on a particular legal understanding of what it means to represent speech directly. Courts in the early modern period, for example, were concerned with content or substance and hence a kind of lexical or meaning-related accuracy rather than exact accuracy and verbatimness in terms of formulations and grammar (cf. Kytö & Walker Reference Kytö and Walker2003; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2008: 566; Moore Reference Moore2011: 88–98; Grund Reference Grund2017: 63–4).

Indeed, in the context of the OBC, there is evidence that the language was manipulated in various ways by the recorders of the documents. Thomas Gurney, who was active in the second half of the eighteenth century, indicates that his recording strategy was not necessarily focused on the exact words used, but on the substance of what was said (Huber Reference Huber2007: section 3.2.2.2). Traugott (Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011) has shown that the OBC recorders (or ‘reporters’ in her terminology) added often highly evaluative commentary, sometimes explicitly addressed to the reader (see also Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2008: 568). Such overt reader address declines in the eighteenth century and appears to be absent after the late eighteenth century, as the reporting and publication standards of the proceedings were transformed (Traugott Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011: 77; see section 3).

Considering the flagged intrusions identified by Traugott (Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011), it is also possible that the recorders made less overtly signaled changes (as also indicated by Gurney's approach to recording). This may have involved taking away the exact language and replacing it with more expressive, evaluative or legally more important language (depending on the time period of the proceedings): in the early publications of the proceedings in the eighteenth century, the focus was on the shocking or sensational aspect of the proceedings, which may have led recorders to highlight such aspects of the trial with particular speech evaluations. On the other hand, by the late eighteenth century, the record was supposed to represent a ‘true, fair, and perfect narrative’ of the trial proceedings (Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. b), and the focus may have been on the legal formalities. Recorders may thus have replaced particular evaluative adjectives from witnesses (or others) with similar, near-synonyms, such as replacing provoking with the less common, but perhaps more technical aggravating. That would follow the principle of retaining substance.

Revealing such potential dynamics is not straightforward of course. Enabling the exploration of possible scribal manipulation, the OBC gratifyingly includes information on recorders involved in initially taking down the records; their names are often specified in the front matter of the published proceedings (Traugott Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011: 72; see also Huber Reference Huber2007). If we first focus on the specific adjective usage, correlating the usage of specific speech descriptor adjectives and recorders does not highlight any particular pattern. No recorder appears to have applied a favorite adjective indiscriminately; rather, all recorders reveal a number of different types. Not surprisingly, some adjectives are more commonly used by some recorders than others. For example, six out of seven instances of coarse and three out of four examples of blackguard appear in records written by Henry Buckler, who was active in the first half of the nineteenth century. But such patterns may be influenced by the uneven time coverage and the different sizes of the corpora over time as well as the uneven time the recorders were operating. Particular language phenomena may also have been the focus of evaluation at different times or in different cases. Indeed, as noted in section 4.1, it is important to remember that many of the adjectives are not substitutable in the sense that they express exactly the same evaluation and sentiment.

More broadly, whether speech descriptor+language formulations were part of censoring carried out by the recorders (or by authorities or publishers) is more difficult to determine. We would perhaps expect to find a more streamlined and systematic usage (equivalent to ‘bleeping’ of swear words in the OBC; Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016) if that were the case. And, of course, the fact that individual words or parts of words in strings of abusive language were left out but not the whole string shows that authorities and publishers were willing to leave explicit language in the records, perhaps in order not to have ‘judicial authority … jeopardized’ (Devereaux Reference Devereaux1996: 491) or in order to appeal to a readership that was looking for salacious detail (see section 3).

Overall, then, it is likely that we are seeing the evaluation of the speech reporter (whether the witness, defendant or the court), although the influence upon the usage from previous testimony, from the court, publishers or the recorders of the statements cannot be discounted.

4.3.3 What is the goal of the evaluation?

The function of speech descriptor+language was clearly not the same across the board for different users. Here I focus on the use by witnesses and victims, whose usage predominates in the data (463 out of 541 instances). There are strong reasons to think that not providing the actual language is a strategic move for many of the speech reporters. One reason for using speech descriptor+language would be to avoid repeating words and formulations that are deemed generally inappropriate, offensive and/or a sign of lower class. As noted in section 4.1, throughout the period covered by the OBC, using bad language had clear social connotations: it was seen as ‘irreligious’, indicative of ‘a lack of education’ and a sign of lower class (McEnery Reference McEnery2006: 99). What we see in the use of speech descriptor+language, then, may be an avoidance strategy. Minimal indication of the actual original language allows the language reporter not to have to use language that was associated with undesirable qualities. Even if the language is not the speech reporters’ originally, using the language verbatim – or even using particular terms – may have been seen as ‘tainting’ the reporting speaker as well. At the same time, the speech descriptor+language also enables the speaker to express their (mostly) negative evaluation of and stance toward the speech and hence to distance themselves from the speaker and the connotations of the ‘bad’ language (cf. Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007: 163).

Another reason that is tied more closely to the legal context is that, by not citing the language as such, the speech act or evaluation becomes the focus. In other words, the reporter assumes interpretive authority and does not give interpretive opportunity to the reader or hearer (Collins Reference Collins2001: 6, 70–1, 125, 273; Walker & Grund Reference Walker and Grund2017: 15, 17). This means that the reporter does not allow the court officials and jury to weigh and interpret the words for themselves, perhaps suspecting that they would miss the point, or miss the impact that the language had for the speech reporters or other targets of the language. Perhaps the jury would have missed that the language was shocking to the witnesses or a threat unless that was pointed out to them.

Speech reporters use various mechanisms to further frame the represented speech in this way, especially by modifying the speech descriptors or in framing the speech descriptor+language sequence as a whole. In around 170 instances, the adjectival speech descriptor is scaled up with a boosting intensifier (such as most, rather, exceedingly, grossly and especially very), as in (30). The amount of bad language can also be stressed with a number of quantifiers, such as a good deal of, a great deal of, a lot of, a volley of, all manner of and much, as in (31). There are around 40 instances of such quantity-modifying phrases. Finally, perhaps related to the avoidance strategy outlined above, more infrequent modifications stress that the language was so bad that it cannot be repeated, as in (32) (cf. Widlitzki & Huber Reference Widlitzki, Huber, López-Couso, Méndez-Naya, Núñez-Pertejo and Palacios-Martínez2016: 319). Such examples are in some ways related to the boosting uses we see in (30), but they scale up the ‘badness’ even further.

(30) he went about twenty yards, and uttered very ugly language (t17910216-26)

(31) he gave me a great deal of abusive language (t17911207-29)

(32) but she was using such filthy language I can not repeat it (t19070108-30)

Again, in most of these cases, the witness does not reveal the actual content and formulation of the original speech. This strategy, then, gives additional focus to the speech descriptor and hence the evaluation and the impact of the words on the speech reporter. Emphasizing the severity, the abusive and threatening nature, or the indecency of the wording matters for how the witnesses position themselves and others (for the use of intensifiers more broadly and speaker positioning in the OBC, see Claridge, Jonsson & Kytö Reference Claridge, Jonsson and Kytö2020a: 866–8; Reference Claridge, Jonsson and Kytö2020b: 79–80). The witnesses were not only victims of a regular string of abuse, but of language that was more abusive than ‘ordinary’ in terms of quantity and/or severity, and hence the abuser is the more reprehensible. At the same time, these kinds of upscaling devices also have a textual effect for readers of the proceedings (whether court officials or a broader audience): they bring attention to and put the spotlight on the evaluative adjective and its implications (cf. Grund Reference Grund2021: 134). This is not only indecency or abuse, but INDECENCY and ABUSE in (metaphorical) capital letters.

Another goal that is intimately tied to the legal context is to mitigate, deflect or disprove an accusation or guilt. As I noted in section 4.3.1, language is rarely (if ever) the central component of Old Bailey trials. At the same time, language use appears to be seen as a powerful factor in cases that revolved around violence, battery and even murder, even to the extent that provoking language could be seen as a mitigating circumstance (cf. Langbein Reference Langbein2003: 303; Emsley, Hitchcock & Shoemaker Reference Emsley, Hitchcock and Shoemakern.d. c). In this context, we find references especially to the kind of evaluation that had an effect on the hearer or another target (see section 4.2), as is evident in examples (33)–(35).

(33) My passion, by her grossly abusive, provoking language was wrought to an ungovernable pitch (t18110403-46)

(34) he insisted upon fighting him, and gave him a great deal of abusive language, which was what a gentleman or officer could not put up with (t17510703-18)

(35) I had not heard them use any abusive language to provoke the soldier (t18430130-622)

Example (33) is from a case where the victim, the original speaker of the ‘grossly abusive, provoking language’, was killed by the speech reporter. The speech reporter was her husband, and he appears to claim that the language at least partially triggered his violent response. In (34), the case revolves around what triggered a fight between two men, and the speech reporter suggests a social connection: the language was such that someone who has a particular standing and rank would not be able to suffer the language without retaliating. In these and similar examples, it is arguably key that the actual language is not quoted. That allows the speech reporter to focus on the nature and effect of the language, and those aspects can be underscored with the help of intensifiers (grossly) and quantifiers (a great deal of) (as we saw above). Reporting the specific language used would have opened up the possibility for interpretation whether the language was indeed provoking and abusive as claimed by the speech reporters. Sometimes the claimed original language is cited, but even then the speech reporter tries to put their stamp on the interpretation by following up with the speech descriptor+language.

Finally, example (35) comes from a trial that contains a great deal of negotiation between two parties whether abusive and provoking language was indeed used and whether the language led to the accused committing the alleged violent act. The accused, a soldier, appears to have claimed mitigating circumstances from provoking language, and the witness pushes back. This negotiated use is clearly part of a larger set of strategies of stance whereby the witness aligns or disaligns with the accused or accusers and their respective claims (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007: 163).

A fourth, equally important function of speech descriptor+language appears to be to provide character portrayal or characterological evidence. In this context, the evaluation of the language is tied to the type of person the defendant or some other person is perceived or purported to be. This kind of evaluation has both legal and social underpinnings, as illustrated in examples (36)–(39).

(36) The prosecutor said, before the magistrate, that in consequence of some ill language made use of, it gave rise to the suspicion that we were bad characters (t18130113-60)

(37) she went into her own house, he followed, and dashed her down again with violence, using violent language (t18481218-314)

(38) he began his blackguard language — I went into the shop — he came and placed the steps in front of the door — I went to take them from him, and he threw them with all his violence at me, and bruised my knuckles (t18500408-768)

(39) she began to swear and curse, and to use language not fit for a woman (t18520614-626)

In example (36), the connection between language and character is spelled out as the speech reporter notes how the ‘prosecutor’ (which here means the plaintiff rather than an officially designated member of the legal system) equated ‘ill’ language with the speaker and another person being ‘bad characters’. In other words, language is seen as indicative of character or group traits, here of course in a very negative sense (cf. Traugott Reference Traugott, Pahta and Jucker2011: 75).

This kind of connection is rarely made explicit in the records; instead it seems frequently to be implied, as in (37) and (38). In (37), the defendant is described as violent and the language is also said to be violent. Exactly what violent language would entail is unclear and presumably not important: we just get a sense of an all-around violent offender in language as well as behavior. In (38), the deponent seems to suggest indirectly through the language that the person is a criminal, lower class or generally depraved, without saying so directly. Blackguard is of course a multivalent term, with various social and moral connotations (OED, s.v. blackguard). Whether connected specifically to criminality, lower class or immorality (or perhaps some combination of those qualities), blackguard as an attribute of language could be used to intimate that his attacker is a ‘blackguard’ (in some sense of the term) without actually calling him such explicitly (which may have been seen as possible grounds for a defamation suit). Indeed, while not spelled out, many of the descriptors of the nature of the language, such as coarse, filthy, indecent and disgusting, also seem to be used to imply something about the speaker using the words: who would employ words of this kind other than someone who is criminal, depraved or generally disgusting?

We find infrequent examples that focus on gender, as in (39) (see also section 4.2). Here the evaluation is slightly different. It is more social than legal, and the speech reporter's focus is on how a person does not fit into a particular group based on their language. It is clear that the witness disapproves of the woman's behavior in general and seems to underscore this evaluation by making a gender-related determination in terms of her language. These explicitly gendered comments are rare, but the explicit ones are always about women and always found in witness statements by men; they stress the language as unfit or unbecoming of a woman. We do not get the same policing of men's language with gender highlighted in speech descriptor+language.

There is no explicit connection to social class or region. We get a sense that the speech reporter considers something outside societal norms when they mark something as uncivil or improper. There are also references to low, base, inferior or vulgar language, as in (40), but it is not clear that these are necessarily references to social hierarchies, and these instances are overall rare.

(40) the prosecutrix used very low language indeed — the prosecutrix hit the first blow (t18390513-1579)

But again, the understanding of the language described as lower class, as uneducated and as ‘irreligious’ is likely implied. As noted above and in section 4.1, ‘bad’ language was overall viewed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and later) as associated with such qualities and characteristics (McEnery Reference McEnery2006: 99–100). So, by ascribing these descriptions to the language, the reporters may also be suggesting the original users’ status (and value) in society and, for women, their ‘fit’ for what it means to be a woman.

5 Conclusion

We have seen that speech descriptors can be a powerful tool for investigating the dynamics of speech representation and the evaluation of speech in late Early Modern English and especially Late Modern English. I have focused on a constrained slice of the evaluation; speech descriptors can occur with a range of other speech expressions beyond language. But clearly, as indicated by speech descriptor+language sequences, speech descriptors are part of calculated strategies of framing evidence and positioning the witness as well as defendants and others. The speech reporters frequently put the evaluation at the center of the statement rather than the actual words and thus constrict the interpretation of the words. By focusing on evaluation rather than the actual speech, speech reporters can use the evaluation for larger legal and social purposes, such as to underscore or mitigate guilt or cast the original speaker in a particular light (as lower class or unwomanly). In other words, even when what was said is not the central component of legal negotiation, witnesses strategically manipulate the voices of others to put the spotlight on spoken language and frame it for their own pragmatic and social purposes.

More broadly, the study shows that, when we investigate the spoken language of Late Modern English in general or of the OBC in particular, we need to pay attention to various means of speech representation at speech reporters’ disposal. A sequence such as speech descriptor+language referring to a more explicit or detailed representation of the speech obviously provides a clear evaluation of how the speech was perceived or received by the reporter. It is a kind of metalinguistic commentary, which, in the case of the OBC, clearly had important sociopragmatic functions in this legal context; these comments can cue us into expectations related to social and moral behavior. There is potentially important sociolinguistic information in such commentary that can be tied to specific formulations of spoken language. At the same time, when more detail about the speech is not available and speech descriptor+language is the representation, we get a sense of the larger dynamics of speech representation as a tool that is part of the nature of the spoken language of the past. Taking charge of the speech of others by suppressing or backgrounding their voices serves important functions for speech reporters in the situational role they are performing. In the OBC, this role is clearly legal, but also interpersonal and social, depending on relationships between speech reporters and original speakers and attitudes among speech reporters. The speech descriptor+language shows that representing speech is not simply a question of transferring previous speech into a spoken report or straightforwardly translating speech into writing. It is a negotiated process, full of strategic decisions. Paying attention to the decisions and who makes them will give us a more nuanced and deeper sense of what speaking English in the late modern period was like.