Neihan Duanzi 内涵段子 was a seemingly harmless social media portal for videos, memes and jokes in China, similar to Reddit or 4chan. It rarely hosted criticisms of the government or calls for collective action. However, as the site gained in popularity, users began to form offline communities, meeting up and identifying each other in public, sometimes by honking their car horns in a secret code at intersections. In April 2018, the government surprised many by shutting the site down. We argue that this decision reflects the regime's strategy of maximally shrinking non-official public spaces that could threaten the CCP's authority or compete with it ideologically in the future. Neihan Duanzi's large and growing community was not a clear threat to the CCP when it was closed, but it had the potential to transform into one. Using the example of another platform, Sina Weibo (Xinlang weibo 新浪微博), we argue that the key to shrinking this space is the careful targeting of individuals who are influential within counter-hegemonic spaces such as Neihan Duanzi.

While the state could reassert control over these spaces by shuttering all private social media platforms, it benefits from a well-maintained and constrained private media ecosystem. Once at odds with capitalism, the Chinese state is now using it as a source of stability. Drawing on tech firms’ expertise and continual innovation in social networks, digital payments and targeted advertising analytics, the government can reserve real-world and violent repression for those flagged by algorithms predicting future acts of state subversion. These systems are already in development.Footnote 1 Through the co-optation of technology companies, the state enforces information control and repression with a scalpel rather than a hammer.

The Chinese state has carefully constructed its repression regime to tame citizens via impersonal censorship algorithms, calibrating and customizing its tactics for different individuals and contexts. For many, state security's intrusion into their lives is merely virtual and often covert and unobserved. For a select few who dare to push the boundaries, online censorship may be more explicit and threatening. It may also move from the virtual realm to real-world interaction – home visits, invitations to “drink tea,” interrogations, detentions in a black jail, or worse.

We analyse when delegated, sometimes automated, censorship of online content shifts back to the state's repressive apparatus. The Chinese government delegates online censorship to private internet content producers (ICPs) like Sina and Tencent and compels them to satisfy the government's demand for information control. While much of the delegated censorship work involves deleting or hiding sensitive content, ICPs also selectively report certain content and users back to the government. We seek to understand this reporting system's logic by examining who and what are targeted for handling by the state itself.

We find that “reporting up,” which likely results in direct state repression or co-optation, is targeted towards influential public opinion leaders whose standing and influence may threaten the Party's hegemonic presence in China's online public sphere. Substantive topics, although relevant, matter less than user influence and virality in state efforts to “guide opinion” through direct repressive interventions. Many topics, including topics that have an apparent collective action threat (a political dissident, a workers’ strike), are not reported up unless they achieve a certain degree of virality or influence. By contrast, many viral discussions that challenge the legitimacy of the regime in more indirect and oblique ways (elite defection, ridicule of top leaders) are reported up.

Work by Herbert Franz Schurmann speaks to the state logic of “who not what.”Footnote 2 In his work on the early years of CCP rule, he emphasizes the importance the CCP attached to ideology and organization in its social revolution, which he conceptualizes as a process of destruction and replacement of former elites. Communist control had both ideational and spatial dimensions. Ideology replaced other values and norms of China's old society. Communist organization embedded the Party in all social, economic and political structures and eliminated the old elite, from landlords to factory owners. However, in the second edition of his Ideology and Organization, Schurmann's analysis of the Maoist state during the Cultural Revolution is instructive for understanding how Maoism approached challenges of a new, emerging elite. In Schurmann's analysis, social mobilization, especially of students in the Cultural Revolution, challenged the CCP's organizational dominance. “If power is the key element in organization, authority is the key element in a social system.”Footnote 3

The contemporary context is quite different from that in the late 1960s. However, the emergence of a dynamic private sector, new social classes and independent sources of wealth and social status poses similar challenges to the CCP's organizational dominance. The CCP has attempted to establish and strengthen the role of Party cells in private firms, especially recently. In social media, however, organizational dominance is not possible. Instead, the CCP has developed tactics to reduce the authority of new voices, limit their virality and eliminate or co-opt alternate sources of leadership and influence. The battle for online public opinion dictates an ambitious approach that seeks to allow for online expression while also suppressing the rise of influential voices and viral discussions. Although the government is concerned about the internet being used as a tool to facilitate social movements and protests, it also worries simply if a large number of people online talk about the same thing, a situation it describes as “a public opinion emergency” (gonggong yulun weiji 公共舆论危机) or an “internet opinion emergency” (wangluo yulun weiji 网络舆论危机). Schurmann notes that in the context of an evolving social system in which Communist organization is either not complete or weakened, authority is crucial. Controlling, managing and co-opting authoritative voices online is critical.

In social movement theory, authoritative actors can play the role of broker in the diffusion of social mobilization, protest and other forms of collective action. These influential actors serve as nodes in networks that may then connect. In his study of transnational activism, Sidney Tarrow defines brokerage as the “linking of two or more previously unconnected social actors by a unit that mediates their relations with one another and/or with yet other sites.”Footnote 4 On social media, “big V-users” can easily link up users with no previous connection to each other, spawning information cascades and viral discussions of hot topics.Footnote 5 As we show below, the government is especially worried about viral discussions sparked by influential thought leaders.

The state's evolving response to social grievances since the violent suppression of the student movement in 1989 can help us to understand the tension between increased openness of communication and the state's goal of maintaining hegemony over discourse. In response to the mistakes of 1989, the Chinese state developed a new toolkit, often called “responsive authoritarianism,” which combines targeted repression and broad responsiveness. It has become more tolerant of narrowly expressed, localized and economistic protests and grievances. At the same time, its ability to target and isolate political dissidents and to use repression to silence the regime's most vociferous opponents has improved. With the explosion of social media since 2009, however, it has become more challenging for the state to prevent online publics from broadening beyond initially narrow grievance articulation. The networked and rapid nature of discussion online can unite similarly aggrieved individuals across time, space, class and even language. For example, local scandals in food safety, wage arrears or corruption can be more easily linked to systemic problems in the authoritarian political system, such as the lack of a free press, independent trade unions or close relations between political and business elites. Social media has the potential to transform narrow, local problems to broad, system-challenging threats.

Maintaining responsiveness while containing the threat of the online public sphere is a delicate balancing act. To maintain its responsiveness, a tack which seems to have vastly improved the government's legitimacy,Footnote 6 the central government uses social media discussion to monitor its local agents and mitigate the severe principal-agent problems inherent in China's top-down system. Ever concerned with information cascades that may lead to collective action,Footnote 7 the government seeks to prevent social media from acting as the “single spark that ignites a prairie fire” by controlling public opinion leaders’ virality influence online. CCP training manuals for internet censors specifically reference this problem as the “butterfly effect” (hudie xiaoying 蝴蝶效应), the need to control information before it gets out of (their) control.Footnote 8

This article has four parts. In the first section, we examine control dynamics over time, arguing that the regime has moved from broad-based repression to targeted repression coupled with responsiveness to a broader swathe of the population. The second section uses government manuals and documents on opinion guidance as well as internal censorship logs from a social media company to analyse what triggers commercial censors to report users and information back up to the government. These sources allow us to quantitatively test our model and supplement our results with additional transcript evidence from government sources.Footnote 9 The third and final section discusses the findings.

The Rise of Responsive Authoritarianism and the Challenge of Virality

The Chinese Communist Party's approach to socio-political control has shifted over time. With the acceleration of economic reforms in the 1990s, the government became far more tolerant of protests it viewed as rooted in the socio-economic grievances that accompanied market reform. Small, focused protests multiplied during this time, with protestors limiting their claims and often hiding organizations and leaders. These protests differed not only in their participants but also in their claims, targets and tactics. On the other side, the government began to overhaul the state's repressive apparatus to improve its ability to pre-empt significant challenges while placating reasonable grievances.Footnote 10

Protesters often framed their grievances around economic deprivation and loss precipitated by the disruptive and destabilizing economic restructuring and often unregulated growth. They overwhelmingly, and perhaps even intentionally, articulated their targets as bad local actors, such as corrupt local officials, greedy enterprise bosses or compromised local bureaucrats who failed to enforce central laws strictly when such laws interfered with growth. These lower-level targets were best attacked using tactics that were wholeheartedly moralistic and normative but also, at times, legalistic. As Kevin O'Brien and Lianjiang Li describe, invocation of resistance was rooted in support for the legitimate policies and laws of the central government, and anger that local governments did not enforce them.Footnote 11 Demands were for better rule, not for a new set of rulers.

The shift towards increased state–society dialogue has been labelled variously as bargained authoritarianism,Footnote 12 responsive authoritarianismFootnote 13 and contentious authoritarianism.Footnote 14 Although they emphasize different aspects of the phenomenon, these terms hone in on the notion of protest as an accepted mode of political participation in contemporary China.Footnote 15 Both state and society have adopted new tactics to make high levels of protest in an authoritarian regime sustainable, yielding neither to mass repression or a tipping point towards revolution.Footnote 16 In this game of cat and mouse between state and society, citizens have become adept at constrained escalation, normative morality plays and hiding the degree to which protests had leaders or the organizational capacity to avoid the most severe repression.Footnote 17

The Chinese state has not eliminated repression from its toolkit during this period of responsive authoritarianism. Instead, repressive tactics have become more targeted, hidden, pre-emptive and psychologically sophisticated.Footnote 18 Yanhua Deng and Kevin O'Brien report the use of “psychological coercion” and “relational repression” as strategies deployed by state agents who find it harder to dominate through sheer physical coercion or who have lost the ability to withhold resources, especially from citizens with superior market power. Aggrieved citizens might be persuaded to drop their protest actions at the insistence of colleagues or relatives.Footnote 19 O'Brien and Deng note that “protest control is taking on a person-by-person quality” made possible by the vast increase in state resources dedicated to internal security and stability.Footnote 20

China's progression towards more sophisticated repressive strategies is not unique. In many parts of the world, the use of non-physical, hidden or delegated repression is widespread.Footnote 21 Christian Davenport shows how high-capacity states can disable social movements without overt violence.Footnote 22 Erica Frantz and Andrea Kendall-Taylor find that an authoritarian government's ability to co-opt potential opposition leaders can determine the need for widespread repression as well as enhance its ability to target opponents of the regime.Footnote 23 Sophistication and “person-to-person” contact are not cheap. Observers noted in 2011 that China's internal security budget exceeded its spending on the military. Yuhua Wang and Carl Minzner detail the “rise of the security state” and its multiple tasks of bargaining, compensation, surveillance and repression.Footnote 24

Escalation incentives are baked into the model of responsive authoritarianism.Footnote 25 This is evident from a pithy saying used by protesters: “Do nothing and get no results, do something small and get small results; do something big, and get a big result.”Footnote 26 With the rise of social media, escalation has become far easier at lower cost and with more immediate impact. Online discussions can aggregate narrow and limited grievances (for example, environmental degradation, food safety or lapses in public safety) into encompassing demands for greater transparency, freer media or bottom-up accountability for political elites. Netizens with large followings and influence on social media can rapidly bring these encompassing demands into the public discourse.

The government also has clearly benefited from responsive authoritarianism and has gained legitimacy from its more accommodating stance towards protest and grievances since 1989.Footnote 27 In addition, social media provide the central government with easier access to “real” public opinion, thereby solving the “dictator's dilemma” of not having a true sense of how people feel about a repressive regime.Footnote 28 If people feel they can be open and honest on social media, the regime also benefits informationally. But can the government have its cake and eat it too? How can it sustain high levels of protest and response/bargaining within the context of extensive social media use? And can responsive authoritarianism survive the onslaught of virality?

Empirical Analysis

We draw upon two sources of data: government documents and manuals about “opinion guidance,” and leaked internal documents from the social media company, Sina Weibo. The opinion guidance material serves as transcript evidence, as a record from the government of its logic of control. Our analysis of these documents clearly shows that government outreach to social media “thought leaders” involves a combination of carrots and sticks. We use the leaked internal censorship documents from Sina Weibo to test our theory on information control and to understand what kind of online content and users are relayed back to the government by media companies.

Our findings suggest that the state is most worried about controlling the virality of content, the influence of individuals and the ability of discussion on social media to mobilize and incite. To shape the course of a discussion or to reduce the virality of a discussion, the state eliminates certain types of posts, reduces the influence of leaders and gives a freer rein to the “nobodies” (for example, by allowing small users greater leeway than big users).

Evidence from Government Documents

This section presents transcript evidence of the state's logic of information control which focuses on repressing influential users rather than clamping down on certain categories of content. We draw on data from dozens of Party and government-produced books, documents and manuals about “opinion guidance,” “thought work” and information control whose intended audience is government leadership cadres. The authors of these sources are high-level propaganda and public security officials as well as government-affiliated academics.

The government's logic of opinion guidance described in these manuals is consistent with our theory of “who not what.” The documents show that the state targets its opinion guidance efforts towards users with large followings or viral posts: “opinion leaders” (yijian lingxiu 意见领袖). Most opinion guidance manuals include at least one small section devoted to managing “opinion leaders.” Below, we illustrate this logic with excerpts from government manuals and documents.

The manuals suggest that the Party is concerned that it has ceded too much discourse power to voices outside the system. One manual suggests that “the mechanism for public opinion formation online has changed [as the] means of digital dissemination has broken the [state's] traditional monopoly of discourse.” It laments the fact that social media have “brought about a change of position, from strong to weak among elites, and from weak to strong among the grassroots,” and continues by stating that “because cyberspace has no systemic barriers or binding ideological constraints, all kinds of thoughts, ideas and values have a platform. Different classes, areas and types of media can exchange, integrate or confront these ideas, making the public opinion environment increasingly complex.”Footnote 29 In the excerpts presented below, the state appears fearful of opinion leaders’ ability to organize individuals around counter-hegemonic ideas. The passages suggest that in order to confront the expanded space for counter-hegemonic discourse brought by the internet, cadres must engage with opinion leaders who occupy the most social real-estate in the online opinion field. Manuals direct cadres to pay particular attention to “‘big V’ users who have many fans and followers, [because they] decide the development of online opinion events or the formation of topics of discussion.”Footnote 30

Manuals consistently stress the importance of opinion leaders in the state's opinion guidance efforts; they also agree on the metrics cadres should use to track and identify such leaders. One suggests the importance of two key metrics: re-post counts and fan/friend counts. According to this manual, “Weibo's special model for information dissemination makes it much easier for social media surveillance workers to identify opinion leaders and the root source of opinions.”Footnote 31 Another manual elaborates on the logic behind targeting users based on these variables, citing internal government research on Weibo:

[In] over 30 viral opinion incidents on Weibo between 2011 and 2012, there were only 7,584 viral posts where the number of retweets surpassed 500; a mere 305 Weibo users authored 5,047 of these posts. Moreover, these 5,047 posts [were the root source of] 66.5 per cent of all total posts and 80 per cent of all retweets and comments. Although the public opinion space seems complex and untenable, in reality, it is largely controlled and led by a small number of “big V” users.Footnote 32

The authors of this manual suggest that the state should balance its dual goals of responsiveness and control by regularly approaching opinion leaders, guiding them towards consensus and learning from their perspectives:

We must communicate with them, seek consensus and let them make suggestions from a rational and constructive perspective instead of publishing aggressive and inflammatory extreme speech as they please … it is necessary to maintain close contact with them, through regular or irregular meetings or online exchanges, to take the initiative to invite them to visit major public projects.Footnote 33

The manuals indicate that the state is keenly aware of the agenda-setting power and social import of celebrities, intellectuals and artists online.Footnote 34 Such individuals can “set a new agenda to lead the public to focus their attention elsewhere, resulting in a change in the overall direction of public opinion.”Footnote 35 One manual discusses the case of a high-rise apartment fire that killed 58 people in Shanghai in 2010. It records that “changes in the agenda of discussion of this event were closely related to the actions of opinion leaders.” In the aftermath of the disaster, celebrity blogger Han Han 韩寒 and other famous journalists brought to light systemic issues behind the fire on social media platforms. Public outcry reached a fever pitch after a popular blogger organized a “public mourning event that attracted 100,000 participants in Shanghai.” This protest was organized around the systemic problems articulated by Han.Footnote 36 The state, in turn, increased pressure on Han Han, who has since ceased his once prolific and acerbic blog writing.Footnote 37 At the end of his blogging career, he famously remarked that “influence belongs only to those with power … they own the theatre, and they can always bring down the curtain, turn off the lights, close the door, and turn the dogs loose inside.”Footnote 38

To prevent opinion leaders from fomenting challenges to the state, manuals stress the importance of “institutionalizing specially selected opinion leaders” as well as “discovering, cultivating, training opinion leaders and encouraging leadership cadres to act as opinion leaders.”Footnote 39 One source stresses that opinion guidance should prioritize co-optation rather than repression, even when users are posting inflammatory information, a concept with revolutionary CCP origins – the “united front” (tongzhan 统战). As Schurmann notes, united front tactics take precedence when the organizational dominance of communist parties is not sufficient, as is the case in the online public sphere.Footnote 40 One manual calls on cadres to “take advantage of united front work with new media individuals” by “unifying with those outside of the Party and outside of the system,” “supporting those with good political values, who are familiar with online rules, and who are influential and popular ‘big V’ users.”Footnote 41 Another manual expands on this:

Develop an online “united front” … do not fight. Look instead for areas of greatest agreement. Maintain the relative independence of opinion leaders, seek common ground on important issues while reserving differences on minor ones, gather and co-opt those with different points of view, deal with individuals on a case-by-case basis, support [those with the] “correct” [opinion] and repress [those with the] “wrong” [opinion].Footnote 42

A different manual similarly stresses that the state should not only focus on co-opting and persuading opinion leaders but it should also tolerate and learn from a plurality of views:

When we identify [grassroots] opinion leaders on Weibo, we must strive to guide them in the right direction through [opinion leaders with the correct opinion]. In particular, we must pay attention to the role of network opinion leaders who are close to the identity of netizens, encourage their positive suggestions and tolerate their radical speech.Footnote 43

These documents seldom instruct users to deploy content-based mechanisms to monitor online speech. Instead, social metrics such as re-post counts and fan/friend counts are viewed as the key inputs to “public opinion early warning systems.” Similarly, public opinion emergency management reports published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences recommend using aggregate search volume and other measures of public attention to identify “hot topics.” These reports suggest that the virality of a post and its author's influence are more important than the content in the state's systems for pre-empting the spread of “harmful information.” One manual confirms this, suggesting that “using suitable technological methods, real-time monitoring of information with high re-post counts can be implemented to contain crises at the first sign of danger.”Footnote 44

Evidence from Sina Weibo Censorship Logs

To supplement the transcript evidence gathered from government sources, we draw on leaked censorship logs from social media company Sina Weibo. These data allow us to test our theoretical claims with actual records on censorship implementation at a social media company.

A whistle-blower at Sina Weibo shared these data with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and they have been made available by CPJ at our request.Footnote 45 These data are logs of censorship implementation that record government directives from various bureaucracies to remove content, report statistics during crises and inform on individuals to the government through Beijing-based government affairs liaisons. Each log can include information on users who have been reported to higher levels, quotations or paraphrased content the government wants to have removed, reports on changes in the perceived level of government monitoring, or the general political situation at a given time. In the logs, managers include decisions and instructions on censorship to be used by Sina's content moderators. These logs are used to share information between employees working on different shifts.

Logs sometimes give instructions to employees to “report up” or “report data” to government affairs liaisons in Beijing who cooperate with supervising Beijing propaganda and public security bureaucracies. Although we cannot wholly disambiguate between “reporting up” to facilitate repression and “reporting up” to facilitate co-optation, we know online speech and activity are often invoked by state security agents when they engage (“drink tea”) with citizens. Reports by NGOs show online activity can be the trigger for government repression through “drinking tea” visits, arbitrary detention and arrest.Footnote 46 However, our analysis only covers the first step of reporting back to the government.

In total, there are 8,427 individual logs in our data. Logs can comprise notes related to government directives, management censorship decisions, work guidelines, employee duties and other administrative instructions. Logs disseminate management decisions about how or when to implement government directives to the large team of content moderators employed by Sina. A log will usually include descriptions or excerpts of content along with instructions to employees on how to proceed with content moderation. While many datasets related to censorship capture only keyword-based censorship or manual content review, these data include logs about both. This dataset includes the complete set of logs from 2011 to 2014. For this paper, we analyse only logs from 2012. We do so to limit the analysis to a single year under the Hu and Wen administration. In other research, we explore the full range of data and the changes in censorship behaviour that occurred in the early Xi Jinping 习近平 administration.Footnote 47

Limitations and scope conditions of logs

Because these logs are from a single social media company, there are limits to the external validity of our inferences. We do, however, have reason to believe our inferences can generalize to other social media companies, particularly Tencent (Tengxun 腾讯). Several logs indicate that Sina Weibo's competitor Tencent receives the same directives from the State Council Information Office, Shenzhen-based regulators and the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Tencent, like Sina, delays implementation or even disobeys directives when doing so gives them a competitive edge.Footnote 48 Additionally, the market capitalizations of Sina and Tencent were similar when these logs were written, which means both had similar leverage when it came to negotiating government directives.

The logs indicate that tech companies in China cooperate and influence each other's censorship decisions. For example, a log from 7 May 2013 discusses how Sina Weibo cooperates with Baidu (Baidu 百度) when developing content filtering keywords.

Even a conservative approach to inferences drawn from these logs does not diminish their significance. Sina Weibo is a large and popular social media company in China. During the time of the logs, it was the most popular microblogging platform and was ranked in the top three of all domestic social media companies by monthly active user statistics. During the time of the analysis, Sina Weibo boasted over half a billion registered users.

Although we cannot fully verify the integrity of the source of the leak, we have been assured by the source and the CPJ that the logs comprise a comprehensive set of internal orders of Weibo censorship departments between 2011 and 2014. Although we are confident of the integrity of the data, our additional analysis of state discourse in “opinion guidance” manuals and documents guards against the possibility of results that are confounded by idiosyncrasies of the log data.

Content-coding and variable definitions

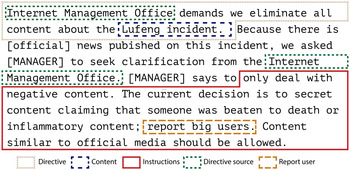

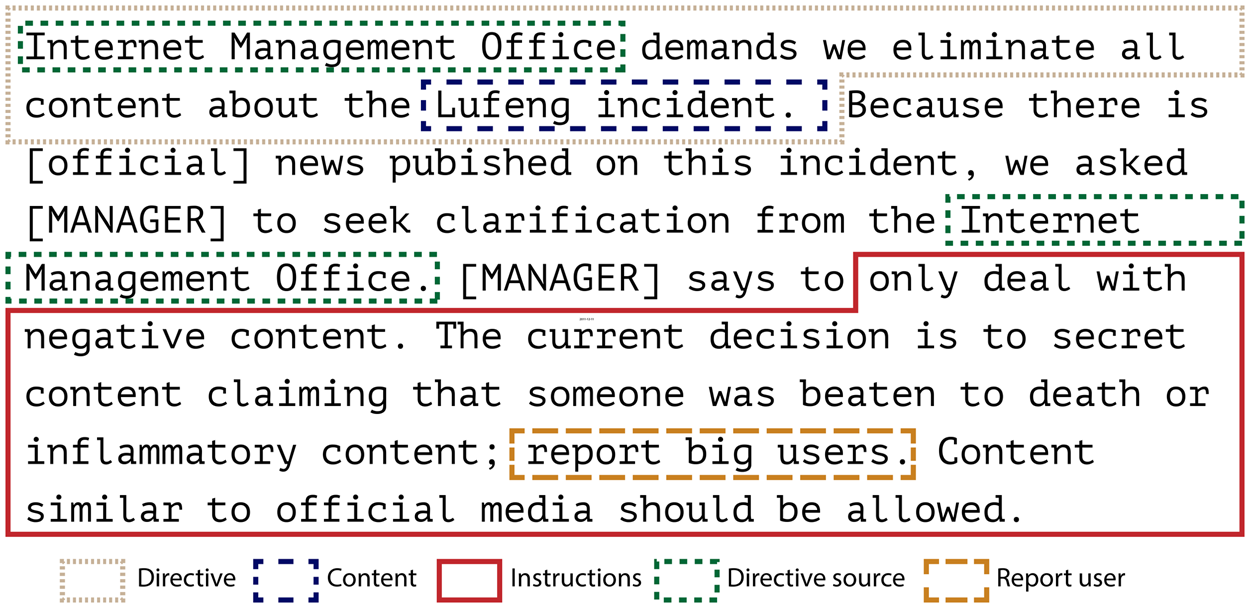

We code each log according to several content and instruction variables, defined in Table 1.Footnote 49 Content variables reference the category of content targeted for censorship. Instruction variables refer to instructions on how to handle content rather than the topic category itself. Instructions refer to conditional statements in the logs, for example: “delete content that is attacking the Party and government” or “report users with more than 10,000 followers.” See Figure 1 for an example of a censorship log and the coding of the log's raw text. The three content variables used in this analysis – collective action, government criticism and local government corruption – are drawn from findings in the existing literature. Gary King, Jennifer Pan and Margaret Roberts together contend that the Chinese state tolerates government criticism while targeting threats of collective action.Footnote 50 Martin Dimitrov and Peter Lorentzen argue separately that the government allows for social grievances to be aired so that higher levels of government may collect accurate information about their lower-level agents.Footnote 51

Figure 1: Example of a Censorship Log and Variable Types

Table 1: Variable Descriptions

We calculate instruction variables using inductively developed keyword dictionaries. The detailed descriptions of variables used in this analysis are presented in Table 1.

Empirical Strategy

We measure the correlation between content and instruction variables and the “reporting up” of users to the authorities with a logistic regression model of log data from 2012. According to our theory of “who not what,” we do not expect content variables to correlate with “reporting up” and instead expect attributes of the user and perceptions of virality to correlate with “reporting up.” Although content does matter in the state's information control efforts, we argue the state intervenes in information control efforts when a user is influential or if the content goes viral. These attributes are strongly associated with whether Sina will report a user to the authorities. The model's dependent variable captures whether logs instruct employees to report individual users to the authorities.

In addition to our regression model, we illustrate these relationships using high profile cases from the logs. These cases are broadly representative of our interpretation of the dynamic between commercial censors and the state, but they vary in their level of political sensitivity and potential for collective action. The first case is a viral story about the citizenship of a high-profile journalist. This case is less politically sensitive and has little collective action threat. The second case examines a civil society activist attempting to mobilize supporters to join his movement. This case is politically sensitive and includes explicit calls for anti-regime collective action. Finally, the third case – the Bo Xilai 薄熙 来 incident – is a highly sensitive political case of intra-elite factional struggles, with low potential for collective action.

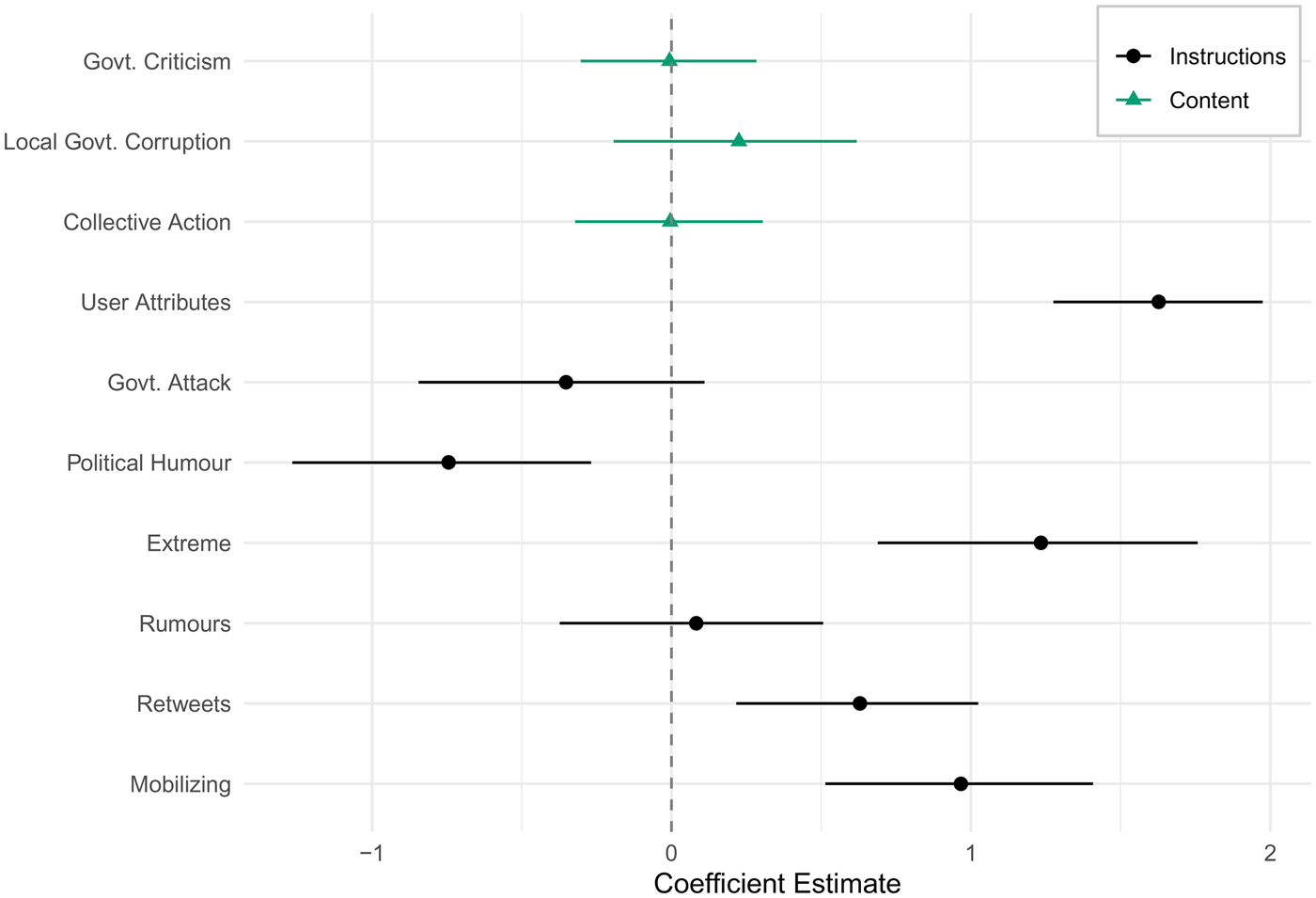

We examine how the content and instruction text in logs are associated with the decision to “report users” or to send information about an individual user to a Beijing-based government affairs liaison who is responsible for coordination with provincial-level bureaucracies, the State Council Information Office and the Cyberspace Administration of China. We present the results of our model in Figure 2 and a regression table in the Online Appendix.

Figure 2: Logistic Regression Coefficient Plot

The biggest predictors of whether content or users are “reported up” are the presence of words that describe the influence of the user mentioned in the log (User) and, to a lesser degree, how “extreme” the content is (Extreme). This includes content that is making exaggerated moral and emotional appeals or advocating extremist positions. Mentions of retweets and the degree to which a post “incites” (shandongxing 煽动性) are also significantly and positively associated with whether a user is “reported up.” As we discuss in the cases below, this category includes posts that incite, even if only abstractly, and can include explicit exhortations for real-world social mobilization, but only if these exhortations incite or stir up strong emotions. By contrast, measured and journalistic statements of fact about collective action incidents do not fall into this category.

No content-based independent variables were significant. The censors instead appear to focus on the framing of content, for example content that “incites” rather than simply content about collective action events. For instance, during an August 2012 taxi strike in the city of Hangzhou, the censors note, “Hangzhou taxis are on a collective stoppage today, protesting the rise in gas prices and the state of the roads. This news can be circulated, but any posts that incite or appeal to other cities should be ‘made secret.’ Report the original poster.”Footnote 52 Similarly, in logs about the 2013 arrest of the 12-year-old daughter of a Tiananmen activist, Zhang Anni 张安妮, who wrote a letter to Barack Obama, the censors allow for discussion of the case, but not “incitement”:

Netizens expressing support for the Zhang Anni incident in Hebei, deal with any inciting content on Weibo, there is no need to delete general discussion at this point.

– Log entry from 10 April 2013.The censors may realize that these are hot button topics and that deletion is not in their commercial interest. It is also possible the state itself is tolerant of more open discussion because while some will sympathize with the striking taxi drivers or young activists, others will criticize them for inconveniencing customers or being insufficiently patriotic. Rongbin Han argues that the state benefits from a more open online atmosphere because it allows “discourse competition” between the government's supporters and opponents.Footnote 53 These posts reveal the delicate path commercial censors must tread. Sina tolerates discussion of collective action and political dissidents up to a point, but reports it to the authorities if the discussion “incites.”

The commercial censors “report up” information about influential “big V” users and viral, inciting news. Online information control is deployed alongside real-world physical repression for the die-hard activists, as we see below in the case of Xu Zhiyong 许志永, the civil society activist.

Selected Cases

In this section, we discuss three emblematic cases of the phenomenon of “reporting up,” selected because they represent three areas of government concern: government legitimacy (the citizenship of Yang Lan 杨澜), political dissidence (Xu Zhiyong's arrest) and elite defection (Bo Xilai's trial). Only the second case involves a clear call for collective mobilization against the state. As such, these cases demonstrate the significance of user characteristics across diverse areas of political sensitivity.

Yang Lan's citizenship

As the censors at Weibo were approaching the end of their night shift on 7 March 2012, they wrote up guidance and instructions for the next shift: “Saying that Yang Lan is a US citizen has already been declared a rumour, directly delete posts of small users, report up big users.” A few days later, they repeated the command: “[Suggesting] ‘Yang Lan is a US citizen’ should be considered fake news; if it is seen on Weibo, delete it, report big users.”

The censors were attempting to shut down a debate raging on Weibo about whether US citizenship was still valuable. On 6 March, there were more than 1.5 million posts on the topic. Some of the discussion focused on the post-global financial crisis state of the US economy, but other netizens took aim at their compatriots: “If you say China isn't good, you are a Western slave. If you say America is good, you are an American bitch. If you say you don't want to be Chinese, you are a wretch and a traitor … If you get a green card and stand on the corner of American streets shouting, ‘I love you, China,’ you are a ‘patriot’.”Footnote 54

Yang Lan, a celebrity journalist and TV host – “China's Oprah Winfrey” – was alleged to be this kind of person. She appeared to be patriotic and had a strong political background (her father was a translator for Zhou Enlai 周恩来), but after making a fortune in China's media market, she had taken citizenship elsewhere. Yang tried to rebut the accusations. Later, she and her wealthy husband, Bruno Wu, threatened to sue.

In the Yang Lan case, the censors treated users differently based on their degree of importance and influence. Sina deleted normal users’ posts when they gossiped about or criticized Yang Lan; they deleted the accounts and reported opinion leaders who did the same. While collective action may have been a concern in this case, it is more likely that the government was concerned about its legitimacy. If someone like Yang Lan, who is well-connected, wealthy, successful and “within-the-system,” is seeking foreign citizenship, it reflects poorly on the CCP. Are elites losing faith in the country's future? Do even the well-connected and wealthy have an exit option should the future take a turn for the worse? The crackdown on the Yang Lan case shut down such questions.

The arrest and trial of Xu Zhiyong

In cases involving well-known political activists, however, the concern with influence is more directly connected to social mobilization and collective action. For example, Xu Zhiyong, a well-known political activist and liberal reformer, first came to prominence in 2003 as part of a group of intellectuals who challenged the state's “custody and repatriation system” under which rural migrants without legal documentation to live in cities were detained. He later opened an NGO, Open Constitution Initiative (Gongmeng 公盟), which championed the rights of migrants to education access in cities and investigated other scandals. He was detained in 2009 and Gongmeng was accused of tax evasion. At the time, Xu was representing families affected by the tainted milk scandal which had caused several infants’ deaths. In May and August 2012, Xu Zhiyong used Weibo to ask for citizen support for Gongmeng, appealing for donations online and calling for unity among Chinese citizens. Instructions were issued for the posts to be “made secret” and for “big V” users who posted such material to be “reported up”:

On May 23rd, Xu Zhiyong used domestic sites (Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo) and foreign sites (Twitter) to incite Netizens to join Gongmeng, to purchase a “citizen” badge. Even calling for people to sign a “citizen promise” … If this content is seen on Weibo, make it secret. Report big users to the authorities.

– Log entry from 26 May 2012.If 10,000 citizens each give Gongmeng 100 yuan, we could do so many things! We earnestly request support for Gongmeng; please believe we will use the money for the places that are most in need of justice. Legal aid assistance account: Xu Zhiyong, China Industrial Bank Beijing Branch, [BANK INFO] Secret posts calling for donations to Gongmeng.

– Log entry from 8 October 2012.In 2013, activists, including Xu Zhiyong, called for greater disclosure of government salaries and wealth. Xu Zhiyong championed this initiative as part of his “New citizens’ movement.”Footnote 55 Demonstrations took place in several cities and many participants were arrested. After being under house arrest for three months, Xu Zhiyong was finally taken into custody in July 2013, charged with “attempting to disturb public order” in August, and then sentenced to four years in prison following a trial in January 2014. (He was released from prison in July 2017.)

During this period of renewed activism around transparency issues, the commercial censors were given many orders to censor information about Xu Zhiyong and, importantly, to report up “big users” and “special circumstances.” Certain users were singled out, including Xu's defence lawyer, Liu Weiguo 刘卫国, and several other rights defence lawyers. On the same day as the following instruction was issued, Liu was detained:

Regarding the issue of several lawyers going to Beijing's Third Detention House to visit the detained Xu Zhiyong, when verifying, make [this information] secret. Increase the number of keywords that are automatically “made secret.” Immediately report up any special circumstances, including the lawyers, Chen Jiangang 陈建刚 and Liu Weiguo. These two say a lot. While verifying, pay careful attention; these words have already been verified.

– Log entry from 18 July 2013With well-known political activists who openly challenge the government, the state's repressive apparatus is neither hidden nor subtle. The commercial censors are told the issue is of great importance, and online discussion is used to monitor particular people both virtually and, eventually, through physical detention and criminal charges. Many of the lawyers mentioned in these posts were later detained in the July 2015 massive crackdown on human rights lawyers across China. Many other “rights defence” lawyers have gone underground since the 2014–2014 wave of arrests.Footnote 56

The Xu Zhiyong case demonstrates the government's desire to shape and guide public opinion rather than just repress the actions of these few or to stop collective action. During the January 2014 trial of Xu, for example, censors were instructed to calibrate censorship carefully:

Tonight at the First Intermediate Court in Beijing, Wang Gongquan 王功权 admits guilt that he and Xu Zhiyong incited people to disturb public order, he has deeply reflected and awaits trial. Related content can be discussed as long as it reflects the media reports. Make secret anything that does not reflect the official line, stop small users and small media from discussing. Discussions in the big media should be verified first, posts with lots of retweets should be carefully reviewed.

– Log entry from 22 January 2014Both the Yang Lan and Xu Zhiyong cases highlight the targeting of influential users as the regime seeks to control what is said and heard about China's elite. The cases are different in the sense that Yang Lan's citizenship is an abstract threat to the CCP's standing, while Xu Zhiyong's exhortation to fellow citizens is a concrete call for social mobilization. It is no coincidence that these cases involve a famous lawyer and an even more famous journalist, both of whom form part of China's new professionalized and cosmopolitan elite. It is not just what they say and do online that is so critically important to the Party, but also what other people say about them.

The Bo Xilai scandal

The importance of external elite voices was apparent during the 2012–2013 power struggle, and potential coup, which pitted Chongqing Party secretary Bo Xilai against the incoming leader, Xi Jinping. As the scandal unfolded, influential users who expressed support for Bo were reported up to the authorities. Additionally, the government demanded that Sina Weibo monitor and report public opinion data at fixed intervals. It is clear from the log below that Sina implemented requests to report data about public opinion related to Bo Xilai. This log serves both an informational role and a repressive role:

Handling Bo Xilai-related posts: Total posts censored, among them, support for Bo (#, %), ridicule [of Bo] (#, %), re-posting foreign media (#, %), other (#, %). [Also report] whether or not there are any influential users directly supporting Bo. Also, today's Bo Xilai reporting should be calculated according to the following intervals. The reporting up schedule has been revised to the following three time slots: 10:00, 18:00, and 23:00.

– Log entry from 12 April 2012[Keep track of the] number of deleted and filtered posts about Bo Xilai and Wang Lijun, the number of deleted and filtered comments, how many of these articles oppose the way the central government has handled Bo Xilai, are unsatisfied with the results of the investigation of the case, how many are republished from foreign websites, and other related information. The reporting timeline has been changed as follows to these three times: 11:00, 16:00, and 23:00.

– Log entry from 13 April 2012The Bo Xilai scandal was what the Party calls a “sudden, unexpected emergency” (tufa shijian 突发事件). As such, immediate public opinion responses were followed with data collection and planning for more comprehensive public opinion interventions as the situation developed. More targeted interventions required information gathering, which is why Sina was asked to report data to the authorities. As the crisis unfolded, more specific topics of conversation became off limits, not because there were pre-existing procedures to target specific categories of content but because the goals of “opinion guidance” are to reduce the visibility and influence of content propagated by counter-hegemonic voices and increase the visibility of state narratives. A more specific log on the Politburo Standing Committee's inspection tour of Chongqing following the incident provides such an example:

Today [MANAGER] published content moderation instructions for the inspection tour of Chongqing by the nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC):

1. Manage all content (including news) related to the inspection tour of Chongqing by the nine members of the PSC.

2. Manage all rumours about government, the most important being: foreign reports and speculation, reports from foreign media where the size of discussion in the comment section is particularly large, content originating from sensitive individuals, commentary on Sina Online official accounts, and headline news.

3. For users who publish rumours, the public security department will investigate and deal with the person at the time, and at the same time, investigate the criminal responsibility of the person in charge of the website.

4. In mid-May, government rumours were thoroughly cleaned up, and whenever one appeared, the owner of the website was required to go to a meeting at the city bureau and rectify their errors.

Later, as Bo Xilai was tried in the Jinan Intermediate People's Court, the logs portray a more planned and carefully executed opinion guidance strategy. Many China watchers expressed surprise when the Bo Xilai trial was covered live on Weibo, but this was done carefully and with Sina Weibo's cooperation.Footnote 57 On the opening day of the trial, Weibo was instructed not only to target categories of off-limits content but also to aid the Party in its efforts to set the agenda by heavily controlling counter-hegemonic discourse from “big V” users and various non-official media accounts:

All comments discussing the matter from big media users and “big V” users are to be reviewed first before publication, one hour after the broadcast, lock comments. Directly prevent comments on small media accounts.

– Log entry from 22 August 2013In several related logs, content moderators were instructed to report up influential users and hide all content that was not exactly as reported by the Jinan Intermediate People's Court's Weibo account. By restricting discussion to official channels and focusing primarily on influential counter-hegemonic voices, the state was able to appear open, transparent and legitimate in its trial of the fallen Party secretary.

In the handling of all three cases, Yang Lan's citizenship, Xu Zhiyong's trial and the intrigue over the Bo Xilai affair, commercial censors deleted or made secret information that could mobilize or incite public opinion, they reported influential users to the authorities, and they also reported up data on public opinion. Such tasks are multifaceted. Focusing solely on repressive practices would be to neglect the more sophisticated goals of guiding public opinion and delivering more accurate information to government leaders about the prevailing thoughts of opinion leaders and the masses regarding controversial topics. However, information about specific users can always be retained for future repressive activities. In an April 2011 log about a taxi- and truck-driver strike, the link between information and repression is apparent:

Strengthen handling of inciting and harmful information about the taxi and truck drivers’ strike against the rise in gas prices, especially information that mobilizes for the 1 June strike. Accumulate related news and retain the IP addresses (of users) with information that incites or mobilizes.

– Log entry from 15 April 2011In an interview, the source of the leak explained that “when some political rumour was spread widely, or during the Tiananmen Square anniversaries, police harassed people based on the information we provided.” The source also recalled a manager instructing employees at Sina Weibo's censorship office in Tianjin to “hand in your big form. The police need it to arrest people.”Footnote 58

Concluding Discussion

This paper contributes to our general understanding of the governance strategies of the Chinese party-state in the virtual public sphere of social media. Building on earlier theories that emphasize the importance of limiting social elites external to the CCP, we find the government is concerned with the power of virality and influence on the internet, a space that cannot be easily dominated simply via Party organization. Attempts to mobilize citizens collectively via online discussions, such as in the Xu Zhiyong episode, are threats to the government's hold on power. However, the government endeavours to limit “counter-hegemonic discourse” even when the threat of real-world collective action is not imminent. Work on social contention suggests that the Party targets influential thought leaders because of their large networks and their potential capacity to unleash information cascades that could undermine CCP legitimacy, encourage real-life collective action or shift public opinion on important topics. Big-V users function as brokers by connecting social media users who may previously have had no connection. Large numbers of online followers have the potential to create the authority and discourse power to challenge CCP dominance.

Maintaining responsiveness and more accurate monitoring of public opinion are essential facets of the government's strategy, however. In a sense, these findings underscore the information problems that confront dictators.Footnote 59 Social media discussion is desirable because it elucidates public opinion trends and social grievances. Nevertheless, it can also be too much of a good thing.

Returning to the exposition of the importance of Party leadership in Schurmann's work, our findings confirm that the CCP is most vociferously interested in constraining the rise of powerful alternative voices and influence.Footnote 60 Schurmann's analysis focuses on the period when the old elite of the ancien regime had been vanquished. Our focus is on a period when social media elevated new voices and allowed opinion leaders to re-emerge independent of the Party. Schurmann's perspective is, however, still helpful given its focus on the role of elites in leadership. The rise of the virtual public sphere created new challenges for the Party in maintaining its discourse power and its organizational hegemony. As the newest battleground for the hearts and minds of citizens, social media platforms are critical spaces for the CCP to inhabit and dominate. New elite voices and opinion leaders must be co-opted or repressed.

The government is intolerant of many topics once they become viral or are circulated by influential opinion leaders. A post's content is less important than who is posting it and how many people are re-posting it. The debate over Yang Lan's citizenship, for example, seems to fall into this category. It posed no immediate threat of triggering any sort of collective action or revolt; rather it was part of a gradual process during which the legitimacy of the Party was undermined and sabotaged by elites and influential opinion leaders.

Schurmann's work is instructive in part owing to its focus on the 1950s, the period immediately after the Communist Revolution when the Party was assembling the building blocks of its rule, and the 1960s (in the second edition), when social mobilization during the Cultural Revolution undermined the CCP's organizational dominance. In the realm of today's social media, the CCP is similarly limited in its capacity to take over all the space offered by the internet, nor does it wish to do so given the advantages of having more free discussion and better information about public opinion. Instead, the CCP focuses on repressing or co-opting voices that could threaten its leadership to counter what Ya-Wen Lei and Daniel Zhou term the “critical” or “contentious” public sphere found on the Chinese internet.Footnote 61 This is an arena in which citizens are exposed to and generate discussion often beyond the confines of the official government position. The critical threat is not the degree to which public opinion is representative, but rather how influential one is: “As the propaganda official put it, in the end, it is those who speak up instead of those who keep silent that influence other people and bring trouble for the Chinese government.”Footnote 62

Despite the relevance of Schurmann's conceptualization of Party governance, it cannot fully capture the complex way in which the CCP manages virtual public spaces in a far more open, diverse and vibrant context than that experienced during the Maoist period. Moreover, more information and the “appearance of freedom” have real benefits for the government, both in terms of its legitimacy and its understanding of public opinion. Maria Repnikova notes that the authorities shape media policy by carefully scouring social media.Footnote 63 She finds, “alongside control, Chinese authorities scrupulously listen to and study public opinion online, engage with and respond to public grievances, and creatively mobilize the public through interactive social media.”Footnote 64 Daniela Stockmann shows that allowing for greater media liberalization with continued content control can bolster people's trust in the news.Footnote 65 Han argues that “discourse competition” between regime supporters and opponents benefits the state by revealing that netizens are not all liberal CCP opponents: there are also true believers, emboldened by the anonymity and the network-building available online.Footnote 66 Finally, Margaret Roberts contends that censorship is more like a “tax” than a simple restriction on information.Footnote 67 Most netizens will never seek out sensitive political topics online or purchase a VPN to read foreign media. As these leaked blogs seem to indicate, the censors do indeed allow for a great deal of discussion online while systematically targeting those few users who have the influence and the public following to cause real damage.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021000345.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Martin Dimitrov, Iza Ding, Jennifer Earl, Dimitar Gueorguiev, Jeffrey Javed, Kevin O'Brien and Rachel Stern for comments on earlier drafts of this paper and to the participants of workshops at the Hertie School of Governance, the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and at Hamilton College for their feedback. This work was funded by doctoral student grants from the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies and the department of political science at the University of Michigan.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Mary GALLAGHER is a professor of political science at the University of Michigan, where she is also the director of the International Institute and a faculty associate at the Center for Comparative Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. Her research areas cover Chinese politics, comparative politics of transitional and developing states, and law and society. The underlying question that drives her research in all of these areas is whether the development of markets is linked to the sequential development of democratic politics and legal rationality. Put simply, she is interested in the relationships between capitalism, law and democracy. She uses her empirical research in China to explore these larger theoretical questions.

Blake MILLER is an assistant professor of computational social science in the methodology department of the London School of Economics. He received his PhD in political science and scientific computing from the University of Michigan in 2018, where he was also a graduate research affiliate in the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies. He was previously a post-doctoral fellow at the Dartmouth College programme in quantitative social science.