No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

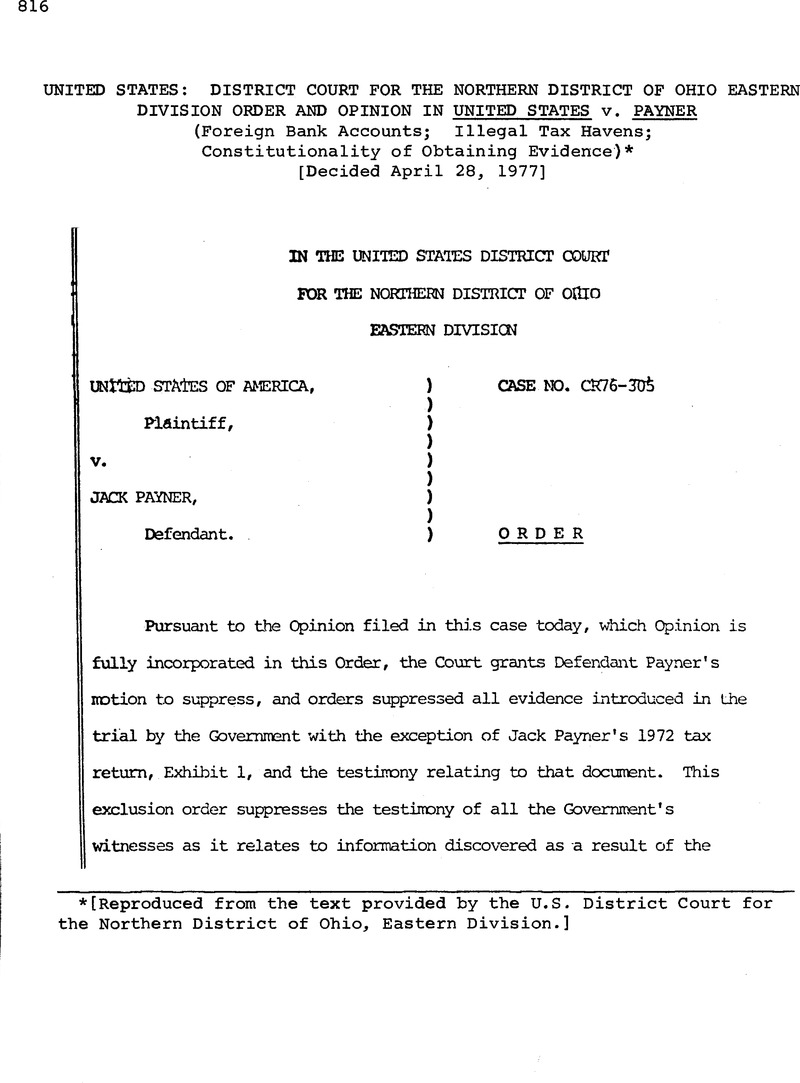

United States: District Court for the Northern District of Ohio Eastern Division Order and Opinion in United States v. Payner (Foreign Bank Accounts; Illegal Tax Havens; Constitutionality of Obtaining Evidence)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1977

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division.]

References

Endnotes

1 The question which Payner allegedly answered falsely road as follows:

“Did you, at any time during the taxable year, have any interest in or signature or other authority over a bank, securities or other financial account in a foreign country (except in a U.S. military banking facility operated by a U.S. financial institution)?” See, Exhibit 1.

2 The defendant waived his right to trial by jury. See, Jury Waiver Form. The Court consolidated the trial on the merits with consideration of the motion to suppress because it was necessary to know whether the Government’s evidence was obtained from a source or sources independent of the search. See F. R. Crim. P. 12(e).

3 See, Transcript of the Motion to Suppress [TRM] 9-10.

4 TRM 24.

5 TRM 133-135.

6 TRM 138.

7 TRM 5. See also footnote 55 infra.

8 TRM 61.

9 TRM 80-81.

10 TRM 81.

11 TRM 89.

12 Transcript [Tr.] 286.

13 TRM 88.

14 TRM 91.

15 TRM 84. On January 11, 1973 when Casper informed Jaffe of his plan, he simply advised Jaffe that he expected to obtain information from an apartment. Casper did not say that he had permission to enter the apartment. or to take the briefcase containing Castle Bank information from the apartment. TRM 105-108. Contrast Jaffe’s rendition of the events on the Thursday prior to the taking of the briefcase, at TRM 155, 172. The Court disbelieves Jaffe’s assertion that Casper told him on January 11, 1973 that he received a key from the owner of the apartment from which he expected to obtain the information. See also, fn. 40, infra.

16 TRM 87, 105, 146-147.

17 TRM 105.

18 TRM 105-106, 155.

19 TRM 108, 155. See also, fn. 40, infra.

20 The following testimony was given by Casper regarding the need for a locksmith who could be trusted:

“Q. Isn’t it a fact, Mr. Casper, you knew you were committing an illegal act, and you wanted somebody who could be trusted to keep his mouth shut about it?

“A. There is that possibility, yes.

“Q. Isn’t that the fact.

“A. Yes.” TRM 112-113. See also, TRM 149-150.

21 TRM 149-150.

22 Although testimony from Sﺢol Kennedy would have been very helpful to the Court in resolving the factual issue of the propriety or impropriety of the Government’s conduct, with respect to Wolstencroft, counsel for the Government never called her as a witness, and the record fails to indicate that she was unavailable. It appears to the Court that it is peculiarly within the power of the Government to produce her, since she worked for its agent and she is totally unknown to the defendant. Therefore, the Court infers from her unexplained failure to testify that her testimony would be unfavorable to the Government by further delineating the improprieties of what Casper himself characterized as the “briefcase caper.” See, TRM 117.

23 TRM 95.

24 TRM 96. See also, TRM 111.

25 TRM 97, 154, 157. Jaffe selected the home of an IRS agent which was located eight blocks away from where Casper met the locksmith. TRM 96. Jaffe selected this location because he knew that Casper needed to hurry and it was located close to the apartment from which the documents were purloined. TRM 155-157. For the number of documents photographed, see, TRM 130.

26 TRM 148-149, 154.

27 Jaffe was asked, “What was the necessity for your being hurried?” He replied, “Mr. Casper had to get the documents and the briefcase back to the apartment prior to the return of the owner.” TRM 154-155.

28 TRM 154.

29 TRM 158.

30 Jaffe in answer to a question stated, “I don’t know who the person was, but he (Casper] had arranged for somebody to observe the lady who owned the apartment and her date, and let them know when they were finished eating dinner, to give him some idea when they would be returning.” Tr. 158.

31 TRM 98-99, 157-158, 174-177.

32 TRM 118, 126-129, 160.

33 TRM 117-118.

34 Jaffe was asked by defense counsel, “Did you care how he obtained it?” and he answered, “I don’t recall thinking that at the time, no sir.” Defense counsel then asked, “... all you wanted was the information, and you did not care how it was obtained?” To which Jaffe responded, “Well, I certainly didn’t expect him to murder anybody for it.” TRM 161. Casper testified that when he handed Jaffe the rolodex file stolen from Wolstencroft’s desk Jaffe “was rather elated.” TRM 119.

35 TRM 116.

36 TRM 115, 123.

37 It is important to note that the seizure was conducted in order to obtain information about depositors in Castle Bank; it was not to gain information about Wolstencroft. Jaffe was asked, “So you had no interest in taking action against Mr. Wolstencroft.” He answered, “Yes, sir.” TRM 165.

38 This conclusion is reached by weighing the demeanor and reliability of each witness who testified and then accepting all, part, or none of what the witness has asserted. See, United States v. Gargotto, 510 F.2d 409, 411, fn. 1 (6th Cir., 1974).

39 TRM 145.

40 Jaffe testified, “Whatever I knew, he [Register] knew.” TRM 172-173. See also, Casper’s responses to questions put to him by defense counsel at TRM 106-110.

“Q. Did you testify, Mr. Casper, before the hearings of the Rosenthal Committee?

“A. Yes.

“Q. And were you under oath when you testified?

“A. Yes.

“Q. Do you recall making these statements:

’I think that the memorandum was January, 1973. The memo said in effect a banker coming through would be coming through the Miami area and there might be some provision that I might have a way of obtaining the information that Mr. Jaffe and I had previously discussed.

‘Now, approximately two days prior to this it really began to jell as to what I might be able to do, and I did something which was inadvertent, and that was that I told Mr. Jaffe that I would be entering an apartment and taking the briefcase out at the time.’

Do you remember that?

“A. Yes, I do.

“Q. Do you remember further on testifying then that:

‘After Mr. Jaffe told me that he had been in touch with his immediate supervisor or superior, and I assumed that to be Troy Register, and I asked him about it, and he said yes, and it has been cleared.’

Do you remember making that statement?

“A. Yes.

“Q. What was cleared?

“A. To the best of my knowledge, that it was permissible to go into the apartment and get a briefcase.

“. . . .

“Q. Had he asked you how you were going to get into the apartment, Mr. Casper?

“A. At that time, no.

“Q. And you didn’t tell him how you were going to get into the apartment?

“A. To the best of my recollection, no. ....

“. . . .

“Q. Mr. Casper, you have indicated that what you stated in the Rosenthal hearings was correct, that Mr. Jaffe told you, ‘Yes,’ and, ‘It has been cleared.’ Is that correct?

“A. Yes.

“Q. Did he tell you what had been cleared?

“A. No.

“Q. Did you ask him what had been cleared?

“A. No.

“Q. Did you ask him to get something cleared?

“A. No.

“Q. Do you remember testifying in this manner, Mr. Casper? You were asked by Mr. Moffitt:

‘Q. What was inadvertent about your statement?

‘A. I blurted it out. He didn’t need to know about this. All I am going to do is supply information. I kind of kicked the bucket anyway, but that was his reaction to this, because immediately he drew up the warning flag, the red flag, and wanted to get clearance on this obviously before anything was done.’

“. . . .

“Q. You said he drew up the warning flag, the red flag. You stated that, did you not?

“A. Yes, I did.

“Q. What did you mean by that when you made that statement?

“A. Mr. Jaffe at that tune said to roe, ‘I have to get clearance.’

” . . . .

“Q. Did he tell you what he had to get clearance about?

“A. No.

“Q. Nor did you inquire?

“A. No.

“Q. And before he got the clearance, you didn’t do anything; is that correct?

“A. That is correct.” See also footnote 20 supra.

41 TRM 3-4.

42 TRM 5. See footnote 55 infra.

43 TRM 26-27, 31.

44 TRM 33.

45 TRM 44.

46 Tr. 221-222, 225.

47 Tr. 232-233, and Exhibit D.

48 TRM 19-20.

49 The Government introduced Exhibit 300 as being the subpoena that produced Exhibit 4. However, the Government’s witnesses were unable to confirm this. See, TRM 20.

50 TRM 36.

51 TRM 18-19, 56.

52 TRM 22. See also, TRM 34.

53 TRM 33-34.

54 TRM 33-34.

55 TRM 164-170. See also footnote 69 infra. This court specifically finds that the investigation of Allen Palmar produced information concerning a connection between the Castle Bank and the Bank of Perrine. The Palmer investigation, along with Casper’s comment to Jaffe in June of 1972 that he (Casper) had once seen what might be a list of the Castle Bank clients, sharply intensified the I.R.S. interest in the Castle Bank. TRM 137-145. However, the Court finds that this information was insufficient to issue a subpoena to the Perrine Bank in 1972, and, for that obvious reason, the I. R. S. issued no such subpoena at that time. See F. R. Crim. P 17(c); United States v. Mitchell, et al., 377 F.Supp. 1326, 1329-1330 (D.D.C. 1974), aff’d in United States v. Nixon, et al., 418 U.S. 683, 698-703 (1974) ["Good cause” required for issuance of a subpoena]. The interest generated by this information caused the August, 1972 meeting of representatives from four regional IPS districts, at which further intelligence gathering plans were made. TRM 144, 62-63, 80-81. However, the IRS still had insufficient data with which to obtain a subpoena from the Perrine Bank at the time of the August, 1972 meeting and therefore in late October, 1972, Jaffe asked Casper to obtain the names and addresses of individuals holding accounts with the Castle Bank. TRM 81. After October, 1972, Casper and Jaffe concocted the briefcase scheme which ultimately furnished the information used to issue the April or May, 1974 subpoena on the Perrine Bank.

56 This Court shall not deal with the seizure of the roloaex. There is no evidence that the information contained on the rolodex has bean used by the Government in any way in the presentation of its case against Jack Payncr. As was made clear in the Court’s Findings of Fact, it was the briefcase material that led to the subpoenas on the Bank of Perrine and thereby the discovery of Exhibit 4, the guarantee. It is the exclusion of the guarantee as the fruit of the unlawful seizure which is the gravamen of the defendant’s motion to suppress. The rolodex was not shown to play any part in uncovering the guarantee, since there was no evidence that the rolodex contained information showing a connection between the Castle Bank and the Bank of Perrine.

See TRM 31.

57 The result of the use of the exclusionary doctrine is often as Justice Cardozo puts it that “[t]he criminal is to go free because the Constable has blundered.” People v. DeFore, 242 N.Y., at 21.

58 It must be remembered that society has a considerable interest in the effective prosecution of criminals. See, Michigan, v. Tucker, 417 U.S. 433, 451 (1974). As the Supreme Court stated in Nardone v. United States:

“Any claim for the exclusion of evidence logically relevant in criminal prosecutions is heavily handicapped. It must be justified by an over-riding public policy expressed in the Constitution or the law of the land. In a problem such as that before us now, two opposing concerns must be harmonized: on the one hand, the stern enforcement of the criminal law; on the other, protection of the realm of privacy left free by Constitution and laws but capable of infringement either through zeal or design.” Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338, 340 (1939).

59 Chief Justice Burger states, “In evaluating the exclusionary rule, it is important to bear in mind exactly what the rule accomplishes. Its function is simple - the exclusion of truth from the fact finding process.” Stone v. Powell, U.S. , , 96 S.Ct. 3037, 3053 (1976) (C.J. Burger, concurring).

60 There are a number of other areas in which courts have excluded evidence. For example, see, Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966); Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 95 S.Ct. 2254 (1975) [Fifth Amendment right to remain silent]; Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967) [Sixth Amendment].

61 It has been argued that the Supreme Court in Jones v. United States, supra and Alderman v. United States, supra did not intend to preclude an accused who was the target of an illegal search but who, as here, was not the person who was actually searched, from having standing! to raise the Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule. See, United States v. Lisk, 522 F.2d 228, 231 (7th Cir., 1975)(Swygert, concurring); United States v. Alewite, 532 F.2d 1165, 1167 (7th Cir., 1976); United States v. Roger S. Boskes, F.Supp. , Case No. 76CR535 (N.D. Ill., March 23, 1977). This Court is convinced from its reading of Jones, Alderman, and Mancusi v. DeForte, 392 U.S. 364, 367-372 (1968), as well as the more recent Supreme Court decisions of United States v. Miller, U.S. , , 96 S.Ct. 1619, 1622-1624 (1976), and California “ankers Association v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21, 41 (1974), that only a party whose expectation of privacy has been violated may raise the unconstitutionality of a search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment.

62 The approval of the exclusion of coerced confessions in Jackson was not solely because of their unreliability but was also because the manner of obtaining the confessions violated principles of Due Process. See, Jackson v. Donno, supra, 378 U.S., at 385-386; Lego v. Twonev, supra, 404 U.S., at 485, fn. 13.

63 There is one more case that bears reviewing. In Irvine v. California, 347 U.S. 128 (1954) the Supreme Court refused to extend the Rochin concept of a Due Process exclusionary rule to a fact situation in which evidence was introduced that the police had entered the defendant’s home without permission on a number of occasions and planted microphones. The Suprecourt in Irvine was split, four Justices joining in an opinion rejecting the use of Rochin, one Justice, Justice Clark, concurring in the judgment only because he felt bound by the court’s decision in Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949), and four Justices dissenting on the basis that the evidence must be excluded because it violated Due Process. See, Irvine v. California, supra, 347 U.S., at 142-149. Since Wolf has been overruled by Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 654, 644 (1961), the vitality of Irvine is questionable.

64 Neither a technical violation of the law, nor police conduct which is entered into in good faith, but which in fact proves to be illegal would be basis for the exclusion of evidence on Due Process grounds. See, Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 607-612, 95 S.Ct. 2254, 2265 (1975)(J. Powell, concurring); Brewer v. Williams, U.S. , , 97 S.Ct. 1232, 1250-1251 (1977)(C.J. Burger, dissenting).

65 There is no standing problem in this case in regard to the Fifth amendment Due Process question. In the Fourth Amendment area, exclusion deters violations of the core Fourth Amendment interest, an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy. The Fourth Amendment expectation of privacy of a defendant such as Jack Payner was not violated by the IRS breaking and entering into Wolstencroft’s briefcase and Kennedy’s theft of Wolstencroft’s rolodex file. In the normal case, where officers acting in good faith, technically violate an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy, third persons, such as Payner, are not accorded standing to exclude the fruits of the illegally obtained evidence because such third persons are not asserting an intrusion into their own expectation of privacy and the police conduct is not outrageous. In such a situation the Janis balance of interests test favors admissibility because no party’s constitutional interest is vindicated by exclusion, and the character of the police behavior, i.e., unconscious, unintentional violation of the Fourth Amendment, cannot be deterred by exclusion. However, under the Due Process concept, the Janis balancing test shifts markedly in favor of extending standing to third parties, such as Payner, to raise the exclusionary rule because an element of the Due Process violation is outrageous j official conduct which violates the constitutional rights of an individual, situated like Wolstencroft, in a fashion which is knowing, purposeful, and with a bad faith hostility toward the right violated. Such intentional bad faith conduct is as susceptible of deterrence as any crime committed purposefully by an ordinary civilian. Compare, the balancing approaches discussed in Stone v. Powell, U.S. ", , 96 S.Ct. 3037, 3049-3052 (1976); United States v. Martinez-Fuerte, __ U.S. __, __, 96 S.Ct., 3074, 3031-3087 (1976); United States v. Janis, U.S. , , 96 S.Ct. 3021, 3031-3035 (1976); United States v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338, 348 (1974); United States v. Peltier, 422 U.S. 531, 537-533 (1975). Furthermore, in a case such as this, were the Court finds that the person who is the object of the outrageous governmental conduct, was never himself the ultimate target of the governmental investigation, then the Court must furnish those persons who are the ultimate targets with standing to raise the exclusionary rule in order to insure that some party is available to litigate the question of the Government’s outrageously unconstitutional activity. Without such an expanded Due Process exclusionary rule standing theory, the Government could repeatedly contain outrageous constitutional violations with impunity against citizens, in order to obtain convictions of other citizens, so long as the government agents accept the speculative possibility of defending civil damage actions initiated by the few primary victims hardy and knowledgeable enough to file such an action. Thus, if the Court did not extend the Due Process exclusionary rule to persons situated in Payncr’s position, purposeful, bad faith constitutional violations by the Government might well be capable of repetition, and evade review. Seo, Jones v. United States, 362 U.S. 257, 261 (1960); Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388, 396-398 (1971); Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 430, 485 (1927) (Mr. Justice Brandeis, dissenting) ; Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 125 (1973); Southern Pacific Terminal Company v. I.C.C., 219 U.S. 498, 515 (1911); United States v. W. T. Grant Company, 345 U.S. 629, 632-633 (1953); Compare and contrast, McNea v. Carey, et al. F.Supp. , , fn. 7, Case No. C76-920, Slip Op., p. 7, fn. I (N.D. Ohio, September 30, 1976); United States v. Perez, _ F. Supp. _, _fn. 32 (N.D. Ohio, 1977).

66 The facts surrounding the IRS appropriation of the bank records from Wolstencroft’s briefcase appear to satisfy a prima facie case of criminal larceny under Florida law. Section 812.011 of the Florida Statutes defines “property” as “anything of value, including, but not limited to - real estate, tangible and intangible personal property, . . . Section 812.021(a) of the Florida Statutes states, “A person who, with intent unlawfully to . . . deprive the true owner of his property .... or to appropriate the same to the use of the taker or of any other person: . . . takes from the possession of the true owner, or of any person . . . or appropriates to his own use, or that of any other than the true owner, any property “is guilty of either a misdemeanor or a felony. Significantly, the Florida courts hold that, “In order to convict a person under § 811.021, Fla. Stat., F.S.A., it is not necessary that the elements of common law larceny be proven. . . . It is enough to prove that the defendant secrets, withholds, or appropriates to his own use, or that of any other person, other than the true owner, . . . the property in question.” Thomas v. State 216 So.2d 780, 781 (Fla. App., 1968); see also, F.S.A. §812.021(5). Certainly the list of a foreign bank’s customers, which list is secret under the law of a foreign state, constitutes intangible personal property which has value. In fact Casper was paid §8,000 for that list. TRM 116. The record also clearly shows that Casper took the Castle Bank’s secret customer list, an item of intangible personal property from Wolstencroft and appropriated it to his “own use or that of any other than the true owner” by selling it to the Internal Revenue Service. See, fn. 20, supra.

Jaffe’s active participation in Casper’s crime, as evidenced by his arranging for a place in which to photograph the Wolstencroft documents, and his appropriation of the Wolstencroft materials for his own use as well as the use of the IRS, probably renders him guilty of a Section 812.021(a) violation as a principal in the first degree under F.S.A. §777.011 which pertinently provides:

“Whoever commits any criminal offense against the state, whether felony or misdemeanor, or aids, abets, counsels, hires, or otherwise procures such offense to be committed, and such offense is committed, ... is a principal in the first degree arid may be charged, convicted and punished as such, whether he is or is not actually or constructively present at the commission of such offense."

The type of conduct which the government agents exhibited in connection with the “briefcase caper” was so outrageously improper that it probably satisfies the elements of F.S.A. §812.081 criminalizing the unauthorized appropriation of trade secrets such as secret “lists of customers,” by copying such lists without permission of the owner. See, §812.081(1)(c), (3). Section 812.081 carries a different penalty than a larceny violation under Section 812.021(a). See, Sections 812.081(2), 775.082(4)(a) 775.083(1)(d) and contrast those provisions with the punishment proscribed under Section 812.021(2), (3), 775. 082(3) (d), 775.083(1) (c). See also, fn. 75, infra.

The criminal activity by the government’s agents is this case is particularly distressing because the briefcase information which they seized by means which were violative of Florida’s criminal law, could probably have been obtained both constitutionally and without violating Florida criminal law, if the officers simply obtained a search warrant. From the record as currently constituted in this proceeding it certainly appears that the information which the IRS possessed regarding Allan Palmer’s alleged use of the Castle Bank to hide illegal income from the IRS combined with the information from Casper, clearly a reliable informant, that Wolstencroft would enter the United States with Castle Bank depositors’ records, might well have furnished the Government with probable cause to suspect that the records in Wolstencroft’s possession constituted evidence of criminal tax evasion by sont? American depositors of the Castle Bank. See, United States v. Manufacturers National Bank of Detroit, 536 F.2d 699, 702-703 (6th Cir., 1976). Thus it appears likely that government officers chose to do illegally that which they could have achieved through lawful, constitutionally recognized, processes See TRM 168.

67 As the Supreme Court nas stated: “The Government cannot make such use of an informer and then claim dissociation through ignorance.” Sherman v. Uniteci States, 356 U.S. 369, 375 (1958).

68 Casper admitted on the witness stand that he knew he was “committing an illegal act, and [he] wanted somebody who could be trusted to keep his mouth shut about it. . . . “ TRM 112-113.

69 At trial the following colloqui took place between Mr. Jaffe and ?n attorney for the defendant:

“Q. And didn’t Mr. Hyatt [a Justice Department attorney) in a memorandum to you of April, 1974, indicate that no one had standing to object legally in court to the use of the briefcase matter except Mr. Wblstencroft?

“A. The memorandum was not directed to me, sir.

Q. Who was it directed to?

“A. I believe it was directed to his superiors in the Department of Justice.

“Q. Well, you were familiar with the contents of the memorandum?

“A. Yes.

“Q. And isn’t what I said substantially the contents of the memorandum?

“A. I believe that is substantially the position he took on the memorandum, yes, sir.

“Q. In fact, wasn’t there some discussion, either by written memorandum or otherwise, indicating that they were not concerned with Mr. Wolstencroft because they were only after the other people that were named in the briefcase?

“A. I don’t remember any such discussion.

“Q. Well, do you remember testifying before the Rosenthal Committee; do you remember?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. You did testify?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. Do you remember in a discussion between you and Mr. Mezvinsky, in a question-and-answer session between you and Mr. Mezvinsky - and tell us whether or not this question was asked and whether this was your answer:

‘Q. You have the Hyatt memo stating the activity would not be viewed as illegal or that it should not restrict your future activity, Mr. Jaffe?

‘A. The context he put it was that none of the individuals on the list would have any standing to object legally in court to the use of our information.’

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. And then do you recall this:

‘The particular individual who had the briefcase might be able to assert that defense, but not the individuals themselves.’

“Do you remember that being said?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. And do you remember your saying this:

‘That is right. We had no interest in taking action against him.

“A. That is true.

“Q. So you had no interest in taking action against Mr. Wblstencroft?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. And from what Mr. Hyatt told you, Mr. Wolstnocroft was the only person who had legal standing to object to the material being taken from his briefcase?

“A. I believe he mentioned the bank also had standing.

“Q. And the bank?

“A. Yes, sir.” TRM 162-165.

70 In the context of civil tax litigation this Court has recognized the need to permit the Internal Revenue Service wide latitude in order to thwart taxpayers from engaging in disengenuous practices that shelter income from taxation. See, M.S.D. Incorporated, et al. v. United States of America, F.Supp. , , Case No. C74-498, Slip Op., pp. 10-15 (N.D. Ohio, March 25, 1977). However the balance of interests shifts markedly when the Internal Revenue Service seeks judicial authorization to purposefully intrude upon the fundamental interests secured by the Constitution. In G.M. Leasing Corporation v. United States, U.S. _, , 97 S.Ct. 619, 629-631 (1977), the Government asserted that its taxing interest in conducting warrantless probable cause entries into buildings to seize property subject to tax assessments outweighed the constitutional protections secured by the Fourth Amendment. The High Court expressly rejected the Government’s assertion of a constitutionally recognized tax interest which outweighed the “core” Fourth Amendment interest in premises privacy. See, Silverman v. United States,. 365 U.S. 505, 509-512, fn. 4 (1961). The G.M. Leasing court at __, 97 S.Ct., at 629-630, wrote:

“Rather, the intrusion is claimed to be justified on the ground that petitioner’s assets were seizable to satisfy tax assessments. This involves nothing more than the normal enforcement of the tax laws, and we find no justification for treating petitioner differently in these circumstances simply because it is a corporation.

“The respondents [the Government] argue that there is a broad exception to the Fourth Amendment that allows warrantless intrusions into privacy in the furtherance of enforcement of the tax laws. We recongize that the ‘Power to lay and collect Taxes’ is a specifically enunciated power of the Federal Government, Const., Art. I, §8, cl. 1, and that the First Congress, which proposed the adoption of the Bill of Rights, also provided that certain taxes could be levied by distress and sale of goods of the person or persons refusing or neglecting to pay.’ Act of March 3, 1791, c. 15, §23, 1 Stat. 204. This, however, relates to warrantless seizures rather than to warrantless searches. It is one thing to seize without a warrant property resting in an open area or seizable by levy without an intrusion into privacy, and it is quite another thing to effect a warrantless seizure of property, even that owned by a corporation, situated on private premises to which access is not otherwise available for the seizing officer.

“Indeed, one of the primary evils intended to be eliminated by the Fourth Amendment was the massive intrusion on privacy undertaken in the collection of taxes pursuant to general warrants and writs of assistance. As Madison argued, urging the adoption of a Bill of Rights to restrain the Federal Government:

‘The General Government has a right to pass all laws which shall be necessary to collect its revenue; the means for enforcing the collection are within the direction of the Legislature: iray not general warrants be considered necessary for this purpose, as well as for some purposes which it was supposed at the framing of their constitutions the State Governments had in view? If there was reason for restraining the State Governments for exercising this power, there is like reason for restraining the Federal Government.’ 1 Annals of Congress 438 (1834 ed.).

“The respondents urge that the history of the common law in England and the laws in several States prior to the adoption of the Bill of Rights support the view that the Fourth Amendment was not intended to cover intrusions into privacy in the enforcement of the tax laws. We do not find in the cited materials anything approaching the clear evidence that would be required to create so great an exception to the Fourth Amendment’s protections against warrantless intrusions into privacy.” (emphasis added).

The G.M. Leasing court also noted at, 97 S.Ct., at 631.

“... [W]e are unwilling to hold that the mere interest in the collection of taxes is sufficient to justify a statute declaring per so exempt from the warrant requirement every intrusion into privacy made in furtherance of any tax seizure.” The proposition upon which the Government acted in this case, i.e., that it could intentionally commit a flagrant Fourth Amendment violation against Wolstencroft in order to obtain convictions of third persons like Payner, is the type of purposeful evisceration of the fundamental privacy interests secured by the Constitution which, the G.M. Leasing court concluded, is not sufficiently justified by the Government’s need to enforce the tax laws.

71 Casper himself refers to the Wolstencroft incident on January 15, 1973 as the “briefcase caper. “ TRM 117 (emphasis added).

72 The Court is well aware of the long established doctrine that constitutional questions will be avoided when an alternate means can be employed to the same effect. Burton v. United States, 19G U.S. 283, 295 (1904)["It is not the habit of the court to decide questions of a constitutional nature unless absolutely necessary to a decision of the case."] See, e.g., Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 347 (1936). In this case the court holds that exclusion is required under Due Process and supervisory powers. Tne court deals with Due Process because the Government might well argue that supervisory power to exclude is limited to these instances specified under the federal criminal . rules. Therefore, the court sets forth the Due Process basis for exclusion.

73 In Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Con. Bd., the Supreme Court stated:

“The untainted administration of justice is certainly one of the most cherished aspects of our institutions. Its observance is one of our prudent boasts. This court is charged with supervisory functions in relation to proceedings in federal courts. Therefore, fastidious regard for the honor of the administration of justice requires the Court to make certain that the doing of justice be made so manifest that only irrational or perverse claims of its disregard can be asserted.” Communist Party, supra, 351 U.S., at 124. See also, Mesarosh, supra, 352 U.S., at 14.

74 As discussed in regard to the Due Process exclusionary rule, exclusion on the basis of supervisory power is only done as a last resort.

“The function of a criminal trial is to seek out and determine the truth or falsity of the charges brought against the defendant. Proper fulfillment of this function requires that, constitutional limitations aside, all relevant, competent evidence be admissible, unless the manner in which it has been obtained - for example, by violating some statuce or rule of procedure - compels the formulation of a rule excluding its introduction in a federal court.” Lopez v. United States, 373 U.S. 427, 440.

75 See, e.g., Nardone v. United States, supra, 302 U.S. 379 (1939); Benanti v. Uniteci States, supra, 355 U.S. 99-103; Williarruon v. United States, supra, 311 F.2d, at 444 [” . . . It becomes the duty of the courts; in federal criminal cases to require fair and lawful conduct from federal agents in the furnishing of evidence of crimes."] ; Rea v. United States, 350 U. S., 350 U.S. 214, 216-218 (1956); Wise v. Ilenkel, 22U U.S 556, 553 (1911).

Exclusion under the Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause and federal courts’ supervisory newer is particularly important where federal officers are counseled to gather evidence in a fashion which violates the criminal law of a state and they purposefully violate such criminal laws I in reliance on the erroneous counsel that their conduct is authorized by federal power. If such officers can demonstrate a subjective belief that their “conduct was necessary and proper under the circumstances,” then they are immune from state prosecution, regardless of how flagrantly their actions violate a state’s criminal law. See, Clifton v. Cox, 549 F.2d 722, 728 (9th Cir., 1977)a case in which, under the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, a federal officer who shot and killed an in armed fleeing suspect in the back during a raid on an illegal drug factory was granted a post indictment, pretrial, writ of habeas corpus blocking his prosecution in state court for second degree murder and involuntary manslaughter. Compare, ExParte Neagle, 135 U.S. 1, 75 (1890). In the case of In Re Lewis, 83 F. 159 (D. Wash., 1897) the court, applying the Neagle doctrine, granted a writ of habeas corpus blocking a state robbery prosecution at special employees of the United States Treasury Department and a United States Deputy Marshal who wrongfully seized private papers while executing a search warrant. The Lewis court observed at 160,

“In deciding this case, I do not mean to say that the warrant which Mr. Kiefer issued was a lawful warrant, nor that the proceedings under it were proper proceedings. I do not mean to say that the petitioners were lawfully discharging their official duties in what they did. In my opinion, the warrant itself was improvidently and erroneously issued, and the proceedings were all ill-advised, and conducted with bad judgment. But where an officer, from excess of zeal or misinformation, or lack of good judgment in the performance of what he conceived to be his duties as an officer, in fact transcends his authority, and invades the rights of individuals, he is answerable to the government or power under whose appointment he is acting, and may also lay himself liable to answer to a private individual who is injured or oppressed by his action; yet where there is no criminal intent on his part he does not become liable to answer to the criminal process of a different government. With our complex system of government, state and national, we would be in an intolerable condition if the state could put in force its criminal laws to discipline United States officers for the manner in which they discharge their duties."

Evidently, the Supremacy Clause furnishes federal officers a broad, although perhaps not absolute, see, United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U .S. 1, 8 (1906), protection against state criminal prosecution when they violate state criminal laws while performing their federal duties. The existence of such official immunity for federal officers means that the deterrent effect of state criminal punishment for criminal conduct in their collection of evidence approaches zero. Absent the deterrent effect of state criminal prosecution, the only practical deterrent to federal officers adopting means of federal law enforcement which are criminal under state law, is often the deterrence generated by federal court suppression of the fruits of federal officials’ criminal investigative techniques. The Fifth Amendment Due Process and Supervisory Power concepts, in conjunction with the speculative possibility of civil damage judgments, are certainly appropriate instruments for administering an adequate dose of deterrence. while at the same time preserving an adequate level of criminal immunity for federal officials.

Of course 18 U.S.C. §2236(b) poses none of the deterrence effected by state criminal law against purposefully improper conduct by federal officials when they act on “reasonable grounds” to suspect the person searched committed a felony. Likewise 18 U.S.C. §241 furnishes no deterrence to purposefully unconstitutional conduct by federal officers when the person who suffers an intrusion into his reasonable expectation of privacy is not a “citizen"(perhaps Woistcncroft is not a citizen) or the federal officers do not go in disguise on the highway or on the premises of the person who’s rights are violated."

Therefore, the deterrence rationale for exclusion under either the Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause or Federal Supervisory Power is uniquely compelling when n federal court is presented with evidence which federal officers clearly obtained through their active, affirmative participation in conduct which is criminal under state law, regardless of the Fourth Amendment standing considerations. As the Court discussed above, this is precisely such a case. See, fns. 65 and 66, supra.

76 Elkins v. United States, supra, 369 U.S., at 216-217; United States v. Valencia, supra, 541 F.2d, at 621-622. The need to deter government agents’ purposeful hostility to individuals’ constitutional rights is analogous to the policy rationale for excluding evidence seized in “pretext” searches. See, South Dakota v. Opperman, U.S. , 96 S.Ct. 3092, 3103 (1976)(Mr. Justice Powell, concurring); Amador-Gonzales v. United States, 391 F.2d 308, 313-315 (5th Cir., 1968); Taglavore v. United States, 291 F.2d 262, 265-267 (9th Cir., 1961); McKnight v. United Scates, 183 F.2d 977, 978 (D.C. Cir., 1950); Blazak v. Eyman, 339 F.Supp. 40, 42-43 (D. Ariz., 1971); United States v. Carriger, 541 F. 545, 553 (6th Cir. 1976); United States v. Robinson, 414 U.S. 218, 246-248 (1973)(Mr. Justice Marshall, dissenting); United States v. Lefkowitz, 285 U.S. 452, 467 (1932); Abel v. United States, 362 U.S. 217, 226, 230 (1960); United States v. Perez, F.Supp. , fn. 40, Case No. CR76-346, Slip Op., p. 21, fn. 40 (N.D. Ohio, April 21, 1977); City of Cleveland v. Tedor, Case No. 34622, Slip Op., pp. 3-5 (Cuyahoga County Ohio Court of Appeals, March 4, 1976).

77 The standing problems associated with the Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule, see, fn. 65, supra, are not present in regard to exclusion under supervisory power. See, United States v. Valencia, supra, 541 F.2d at 621-622. Exclusion under supervisory power maintains the integrity of the federal system and deters illegal and unconstitutional police activity. These interests are the directing issue in this case. This is not a case where exclusion is invoked solely to vindicate a technically invalid intrusion into Wolstencrof’s expectation of privacy. The decision of whether to exclude or not is made by reference to the Janis balance or interests test, which test takes into account the standing question.

78 See, fn. 66, supra.

79 The Court made a finding that the government agents knew they were committing an unconstitutional search.

80 See, Government Memorandum of March 15, 1977.

81 The Court notes that the Government did not argue that the guarantee, or the information discovered after the guarantee was found, was attenuated as to dissipate the taint.” Nevertheless, the Court holds that the taint is not attenuated. See, Wong Sun v. United States, supra, 371 U.S. at 487-488.

82 As Justice Holmes stated:

“The essence of a provision forbidding the acquisition of evidence in a certain way is that not merely evidence so acquired shall not be good before the Court but that it shall not be used at all. Of course this does not mean that the facts thus obtained become sacred and inaccessible. If knowledge of them is gained from an independent source they may be proved like any others, but the knowledge gained by the Government’s own wrong cannot be used by it in the way proposed.” Silverthome Lumber Co. v. United States, supra, 251 U.S., at 32. See also, Wong Sun v. United States, supra, 371 U.S., at 416 (quoted with approval).

83 The exclusion includes the testimony of all the Government’s witnesses as it relates to information discovered as a result of the guarantee, notably the testimony of Robert Mintz, Mary Rhodenizer, Samuel Pierson, Carl Brownell, Jr., William Losner, and Susie Vrabel.