In 2017, the city council and mayor of Washington, DC, extended benefits to many Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipients who had reached the federal lifetime limit of 60 months of benefits (Duggan Reference Duggan2017). Explaining the decision to reverse the previous administration's plan to cut back the city's TANF program, Mayor Muriel Bowser's office released a statement saying, “Because we are serious about supporting families to access opportunity, we need to be willing to support them on the individualized path to get there.” Why did the mayor and city council choose to extend assistance to these welfare recipients when Americans, on the whole, do not view those who rely on public assistance favorably? (see, e.g., Gilens Reference Gilens1999).

The literature on state welfare policy points to party control (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Mink Reference Mink1998), women's representation (Cowell-Meyers and Langbein Reference Cowell-Meyers and Langbein2009; Reingold and Smith Reference Reingold and Smith2012), and race (Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Neubeck and Cazenave Reference Neubeck and Cazenave2001; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008) as the major factors shaping state welfare policies. However, this research has tended to analyze TANF as a program affecting one group of people—welfare recipients—without recognizing the differences among those recipients. In this article, I go beyond the traditional explanations of welfare policy variation and argue that perceptions of deservingness and victimhood create specific welfare rules addressing the needs of subgroups within the larger welfare recipient population. Those advocating on behalf of welfare recipients may use these perceptions of deservingness and victimhood to aid the passage of more generous policy. In some cases, the traditional racialized stereotype of the “welfare queen” who abuses the system may be less pertinent in policy making than the “deserving” qualities exhibited by the recipient.

In particular, this article focuses on how states treat survivors of domestic violence differently under TANF and examines the influence of political parties, activists, and interest groups on these welfare rules. Conducting a quantitative analysis of state welfare rules from 1997 to 2010, I find that feminist organizations, who were active in the passage of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and welfare reform at the national level, continue to fight for survivors of domestic violence. When feminist organizations constitute a larger proportion of a state's interest group community, survivors of domestic violence are more likely to be exempt from TANF work requirements. It is not only feminist organizations that are influential in the passage of these accommodations, though. In states with larger proportions of social conservative organizations, survivors of domestic violence are more likely to receive extensions to the TANF time limit and exemptions from the work requirement. That greater proportions of conservative organizations, which traditionally have been opposed to welfare expansion, are associated with more accommodations for survivors of domestic violence speaks to the perceived deservingness of this particular population of welfare recipients.

Moreover, while previous research has suggested that greater women's representation and Democratic Party control leads to more generous welfare policies, I find that neither is a significant predictor of a state adopting accommodations for survivors of domestic violence. That Democrats and female legislators do not play a significant role in the increased generosity of policies for survivors of domestic violence suggests that even policy makers who are usually opposed to generous welfare policies may perceive this subgroup as deserving of aid. In addition to the quantitative analysis, I delve deeper into the cases of Connecticut and New Jersey to examine the extent to which advocacy organizations can represent and speak for their most marginalized members, especially when facing resource constraints. In the absence of a robust relationship between a state's interest group community and its welfare policies, I find that states often provide activity and time limit exemptions to survivors of domestic violence when they are more generous in the provision of exemptions to all TANF recipients.

Both the quantitative and qualitative results in this article testify to the importance of considering perceptions of deservingness when analyzing state variations in welfare policy. The social construction of those who receive public assistance has created a perception that some individuals are deserving of government assistance, while others are undeserving. Given the connection between domestic violence and welfare and the complexities of representing those affected by both issues, those who have experienced domestic violence may be viewed as deserving. In fact, Congress included the Family Violence Option (FVO) in the larger welfare reform bill so that states could exempt survivors of domestic violence from some of TANF's stricter requirements. The provisions of the FVO fit into a larger welfare program designed to maximize state discretion and open the door for interest groups and activists to make a case to policy makers as to who is deserving of government aid.

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION, DESERVINGNESS, AND PUBLIC ASSISTANCE

As described by Schneider and Ingram (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993, 335), the target population of any policy—that is, the person or group affected by a policy—is associated with a social construction, or “the attribution of specific, valence-oriented values, symbols and images to the characteristics.” Writing about social constructions, Schneider and Ingram distinguish between positive and negative constructions, and in their typology, both mothers and children are characterized as “dependents”—those with a positive social construction, but with little political power (336). Dependents learn that they are “powerless, helpless, and needy” and their problems are only addressed because of the generosity of others (342). Feminist scholars have noted that the “family ethic” creates a “gender-based division of society into public and private spheres” that places women at the bottom of the hierarchy and in a position of dependency (Abramovitz Reference Abramovitz1996, 38). Miller (Reference Miller1990, 23) argues that women who do not conform with the family ethic—including unmarried mothers and divorced women—are punished for their manlessness, while women who follow the family ethic are viewed more sympathetically.

The sympathetic social construction of mothers and children also butts against the American value of individualism to create a dynamic in which only certain populations as seen as “deserving” of assistance (Halper Reference Halper1973; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992). The underlying assumption of American individualism is that each person is responsible for supporting himself or herself; nothing is owed anyone by society (Halper Reference Halper1973, 75). Surveys from the 1980s show that the vast majority of respondents believe that people, rather than the government, are responsible for their own well-being (Gilens Reference Gilens1999, 35). Social constructions of poverty, therefore, may portray the poor as disadvantaged people who are victims of circumstance or as lazy people who are responsible for their own poverty.

These two social constructions—of dependent mothers and the irresponsible poor—are combined in the creation of welfare policy. According to Soss, Fording, and Schram (Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008), policy makers draw from public images like the welfare queen when crafting welfare policy. Those receiving welfare are the ones expected to comply with the rules of the program; in exchange for their compliance, they are offered the benefits. When all TANF recipients are stereotyped as undeserving welfare queens, policy is formulated based on the assumptions of the target population that may or may not be viewed favorably (Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008, 539). Advocating for their interests becomes more difficult because of the implicit bias against the target population. This bias, however, is not consistent across the whole group of welfare recipients. As I will explain in the next section, survivors of domestic violence are one such group that may be viewed rather sympathetically among a group that is largely stigmatized for receiving public assistance.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND WELFARE

Women experiencing domestic violence face tremendous obstacles in leaving their abusive environment. A perpetrator of domestic violence may withhold information from the victim, isolate the victim from friends and family, and undermine the victim's confidence and sense of self-worth (NCADV 2015). This psychological abuse contributes to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and may be more harmful than direct aggression. Women are taught to be caretakers, and many feel they are responsible for holding their families together (Poorman Reference Poorman1990). They may fear retaliation from their abuser if they leave or worry that there is no other option for them.

Economically, a perpetrator may control all financial decisions or take away a woman's ability to earn money (Postmus et al. Reference Postmus, Plummer, McMahon, Murshid and Kim2011). Domestic violence occurs in homes of all socioeconomic classes, though research suggests that women living in poverty are more likely to encounter domestic violence than those of a higher socioeconomic status. About 60% of poor women have experienced domestic violence at least once (Browne and Bassuk Reference Browne and Bassuk1997; Kurz Reference Kurz1998), and a similarly high percentage of welfare recipients have experienced domestic violence (Allard 1997; GAO 1998; Postmus Reference Postmus2004). Persistent welfare recipients, defined as those receiving welfare at least 75% of the year, are more likely to experience domestic violence than those who receive assistance less frequently (Danziger and Seefeldt Reference Danziger and Seefeldt2002).

Women who are able to work while experiencing domestic violence often miss work because of the abuse or find that their work performance suffers. Women who experience abuse are also more likely to be unemployed when they would prefer to be working (Lloyd Reference Lloyd1997, 153). An abuser will try to take away the victim's independence and leave her feeling helpless; it is perhaps no surprise, then, that one of the best predictors of whether a woman will leave her abuser is whether she is economically self-sufficient (Kurz Reference Kurz1998, 108). For a woman in an abusive situation, government cash assistance can provide the financial stability necessary to leave.

In this sense, survivors of domestic violence may be perceived as having a different social construction than other welfare recipients. While the stereotypical welfare recipient is associated with the “welfare queen” (described in further detail later), a survivor of domestic violence generates more positive attributions. A domestic violence survivor also more closely aligns with the original intended welfare recipient. When cash assistance to low-income families began during the New Deal with Aid to Dependent Children (later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC]), the primary recipients were families in which the father was absent; aid was intended to keep families together. Though eligibility for welfare programs has expanded over the years, Americans are still more likely to support welfare programs when recipients are perceived to be deserving of the aid or are trying to “improve their lot in life” (Will Reference Will1993; see also Tagler and Cozzarelli Reference Tagler and Cozzarelli2013). A woman who is taking her children out of an abusive situation, therefore, may be perceived as deserving of government aid because it furthers the safety of her and her children. Both policy makers and citizens may look on survivors of domestic violence with sympathy and see government assistance as their only solution.

Advocates against Domestic Violence and for Welfare Reform

Two years prior to welfare reform, Congress passed VAWA as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (Sacco Reference Sacco2015, 1). Since the 1970s, grassroots organizations had been raising awareness of domestic violence to bring what was then considered a private issue into the public sphere. At the outset of the antiviolence movement, activists stressed that violence against women “can happen to anyone” (Purvin Reference Purvin2007; Richie Reference Richie2000). It was antithetical to the cause to point out that certain demographics—including minorities or those of lower socioeconomic status—may be at greater risk of domestic violence. In one respect, this approach was beneficial to the movement, as prominent women's organizations, including the YWCA and the Junior League, advocated for the passage of VAWA (Palley Reference Palley2001). Similarly, during the battle over welfare reform, feminist organizations such as the National Organization for Women's Legal Defense Fund fought in favor of the FVO (Reese Reference Reese2005, 204). Grassroots supporters of the women's movement continued to express their concern about domestic violence; in 2002, survey respondents were asked about the top priority of the women's movement, and in both years, more than 90% of respondents said that reducing domestic violence should be a top priority (Center for the Advancement of Women 2002).

Advocacy continued at the state level, as many states worked with organizations to implement policies supporting poor women who had experienced domestic violence. For example, the Women's Center of Rhode Island—a member of the state's coalition against domestic violence—facilitated assessments and counseling for domestic violence survivors (Stern Reference Stern2003, 61). One of the challenges in implementing the FVO was screening recipients; many were reluctant to disclose their experiences to a government agency (Postmus Reference Postmus2004). Through the Women's Center's partnership with the Rhode Island Department of Human Services, women who participated in the center's advocacy program received a domestic violence waiver (Stern Reference Stern2003, 61). Similarly, in Washington, DC, recipients seeking a work exemption under the FVO were referred to a social services provider to receive a comprehensive assessment (Stern Reference Stern2003, 65).

It is important to recognize, however, that welfare recipients are a disadvantaged subgroup within the context of all women and all those who have experienced domestic violence (Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007). They are, by definition, low-income; therefore, they are less likely to have the financial resources, or the time, to participate in feminist organizations that advocate on these issues. Writing about recipients of early mothers’ pensions during the Progressive Era, Skocpol states that these women were “too busy with struggles of daily life” to place demands on policy makers (1992, 478). These same barriers exist for welfare recipients 100 years later. Citizens receiving means-tested benefits are less likely to report voting (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). They are also less likely to participate in other political activities, such as joining an organization, attending protests, and contacting public officials (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995, 284). Thus, when interest groups are faced with competing pressures, including fundraising struggles and demands from other subgroups, the needs of their most marginalized members may fall by the wayside.

In addition to being low-income, many welfare recipients are also racial or ethnic minorities, which further marginalizes them.Footnote 1 The stereotype of the “welfare queen” is a poor, unmarried, African American mother whose poverty stems from her own laziness and irresponsibility (Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Luther, Kennedy, and Combs-Orme Reference Luther, Kennedy and Combs-Orme2005). Mink argues that many welfare policies are rooted in the stereotype of “reckless breeders who bear children to avoid work” (Reference Mink1998, 22). Reingold and Smith (Reference Reingold and Smith2012, 132) emphasize that welfare policy is not a racial policy or a gendered policy but an intersectional policy drawing from both identities simultaneously. Advocacy organizations and descriptive representation may be especially important in scenarios when policymakers have to confront long-held stereotypes.

Activists during the welfare rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s experienced this same marginalization, as the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) worked with African American and women's organizations. For example, while both the NAACP and NWRO represented predominantly black populations, the NAACP was seen as a moderate, middle-class organization in comparison with the more militant, liberal NWRO (West Reference West1981). Among women's organizations, both the League of Women Voters and the National Organization for Women were active during the 1960s and 1970s in promoting welfare reform (West Reference West1981). These organizations clashed with the NWRO, though, because of disagreements over guaranteed income plans and whether women should be seeking employment outside the home. Even at the height of their advocacy efforts, welfare recipients were not fully integrated into larger interest groups.

In his study of three areas of social policy, Hays (Reference Hays2001) finds little evidence of low-income recipients of government aid advocating on their own behalf but discovers that other types of interest groups—including public and private service providers and intergovernmental groups—provide surrogate representation for the poor. This surrogate representation will never be as true to the preferences of welfare recipients as direct representation because it is biased by the experiences and backgrounds of the surrogates. In some instances, the surrogate's policy preferences may not align with what is in the best interest of the poor (Hays Reference Hays2001, 66), but regardless of how closely the preferences align, the surrogates do have a voice in policies that affect welfare recipients.

Schlozman, Verba, and Brady (Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012, 386) find little evidence of surrogate advocacy for women, minorities, or the economically disadvantaged in their study of economic organization websites. They do find, however, that religious groups as well as liberal public interest organizations are more likely to mention these underrepresented populations on their websites (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012, 388). Schlozman and colleagues conclude that “disadvantaged constituencies should not count on organizations representing other groups or interests to advocate on their behalf” (392). While this may certainly be the case for welfare recipients, it is quite possible that these organizations are involved in narrow provisions of welfare policy out of self-interest.

The representation of welfare recipients by advocates against domestic violence will not be perfect, just as the representation of welfare recipients by feminist organizations will not be perfect. Welfare recipients who are victims or survivors of domestic violence cannot count on outside groups to truly represent their interests, though these groups may certainly be interested in welfare policy as it pertains to domestic violence. Advocacy organizations may help in crafting the social construction of welfare recipients. They can provide examples of how assistance has changed lives and describe their interactions with welfare recipients. If an organization is trying to balance the needs of several subgroups or fighting to stay afloat though, they may spend more time securing funding than telling the stories of those who need help. In a similar way, female and minority representatives may empathize with the struggle of welfare recipients and amplify the voices of marginalized populations, which, in turn, may help create policy change.

Policy Components of the Family Violence Option

With the passage of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), welfare transformed from a system in which a recipient could theoretically receive benefits for life—as under AFDC—to one that placed strict restrictions on the amount of time recipients could receive aid and the conditions under which they would receive that aid, called TANF. Recipients would be cut off after receiving 60 months of federal aid, and during those 60 months, they would be required to participate in work activities or risk being sanctioned. Policy makers and the public alike perceived welfare recipients to be lazy, promiscuous, and dependent on the state; these reforms were seen as necessary to wipe out what was perceived as widespread fraud and abuse within the welfare system.

TANF also provided unprecedented discretion to the states, which resulted in widely different welfare programs across the states. Some states, for example, chose to adopt time limits that were shorter than the 60-month federal lifetime limit, while others chose to exempt some recipients from the time limit. This discretion allowed policy makers to acknowledge that some recipients would not be able to meet these requirements and would need more flexibility. One group of recipients seen as requiring flexibility was victims of domestic violence. To reconcile the competing needs of states to promote economic self-sufficiency with the recognition of the barriers faced by some recipients, Congress included the Family Violence Option in welfare reform, which allowed states to exclude survivors of domestic violence from time limits, work requirements, and child support enforcement.

One of the primary concerns over welfare reform was ending the “culture of dependency” that contributed to poor families remaining on government assistance for their entire lives. Even the name TANF—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families—confronts this lifelong dependency, with a focus on the temporary nature of welfare. The federal lifetime limit on TANF benefits is 60 months, with states having the option of making the time limit shorter or using their own funds to provide benefits past the federal limit. Between 1997 and 2010, the shortest lifetime limit was in Connecticut—21 months—while several other states had time limits of 36 or 48 months. If a state adopts the FVO, the federal time limit can be made more flexible for recipients with a domestic violence waiver.

States can either use exemptions or extensions to provide recipients with extra time on TANF. With an exemption, a state can discount some months from the recipient's total number of months. This in effect “stops the clock” until the exemption is lifted. States may grant exemptions if the recipient is caring for an ill or incapacitated child or spouse or for a few months following the birth of a new child. States can also grant extensions; in this situation, the recipient has already received assistance for 60 months (or the state's lifetime limit). Extensions may be granted in cases when the recipient is elderly and cannot work or is seeking mental health treatment when the time limit is reached. States can also use their discretion to grant extensions to individuals who have complied with all the program requirements but are unable to find work, perhaps because of poor economic conditions in their area.

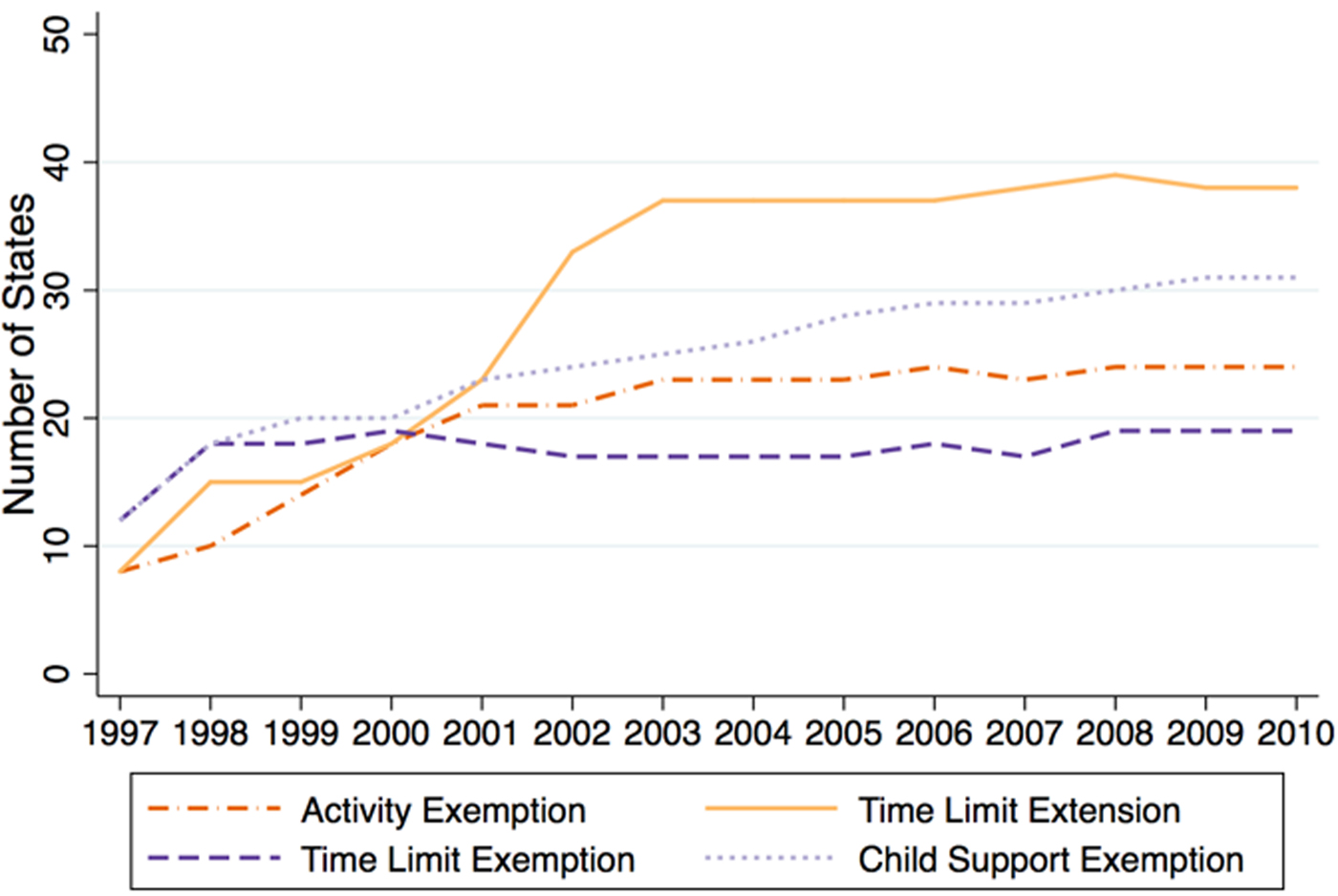

In 1997, seven out of 31 states with lifetime limits granted extensions to those with domestic violence waivers, and 10 states with lifetime limits granted time limit exemptions (see Figure 1). Time limit extensions, however, come into play only when a recipient has reached the time limit, and in 1997 recipients were not at risk of being pushed off the rolls because they had reached the federal or state time limit. By 2002, those who had started receiving TANF in 1997 were reaching their federal 60-month limit. Faced with the prospect of domestic violence survivors being pushed off the rolls, many states adopted time limit extensions. More than 70% of states (30 out of 41) with lifetime limits granted time limit extensions to recipients with domestic violence waivers by 2002. The number of states with lifetime limits granting time limit exemptions only increased to 13 during the same time span.

Figure 1. States Adopting Family Violence Option Rules, 1997–2010

While receiving benefits, able-bodied adults are also expected to participate in work activities. While the federal government defined 12 “core” work activities, states have flexibility in this area as well. Activities include those directly related to employment, including job training and subsidized and unsubsidized work. Other activities are education oriented and include English as a second language classes for recipients who are not proficient in English and basic or high school education so that recipients can obtain a high school equivalency diploma. Finally, there are other activities that are less well defined in their purpose; some activities help recipients overcome personal barriers, such as mental health treatment or drug rehabilitation, while others encourage recipients to become more involved in their community, by participating in community service or providing child care for other recipients.

Similar to time limit exemptions, states may exempt recipients from participating in work activities. Activity exemptions may be provided for pregnant women (how far along a woman must be in her pregnancy in order to be exempt varies by state), ill or incapacitated recipients, or recipients who cannot find child care, among other reasons. The FVO allows states to exempt survivors of domestic violence from work activity requirements; advocates argue that this exemption is necessary because forcing women to go back into the workforce opens the possibility for their abuser to stalk or harass them at work (Mink Reference Mink1998). Many states have embraced this exemption; in 1997, eight states allowed activity exemptions for recipients with domestic violence waivers. By 2000, that number had more than doubled, to 18; as of 2010, 24 states offered work exemptions to domestic violence survivors.

Finally, the FVO provides flexibility in the child support enforcement requirements of TANF. Most single mothers receiving TANF have to comply with state child support requirements—which may include a variety of actions ranging from identifying the father to testifying in court—or risk losing their benefits (Stern Reference Stern2003, 48). When child support enforcement was first incorporated into the welfare system, it was seen as a way to target the “deadbeat dads” who refused to support their children. In the case of domestic violence survivors, however, a woman may not want child support from an abusive partner. Providing information that would allow an abusive partner to legally contact her would ignore “the dynamics of power and control that are at the center of patterns of domestic violence” (Stern Reference Stern2003, 55). Moreover, pursing child support may provoke the abuser's anger against the mother and increase the risk of violence. In 1997, 12 states provided child support exemptions for recipients who had experienced domestic violence. By 2010, the number of states had grown to 31.

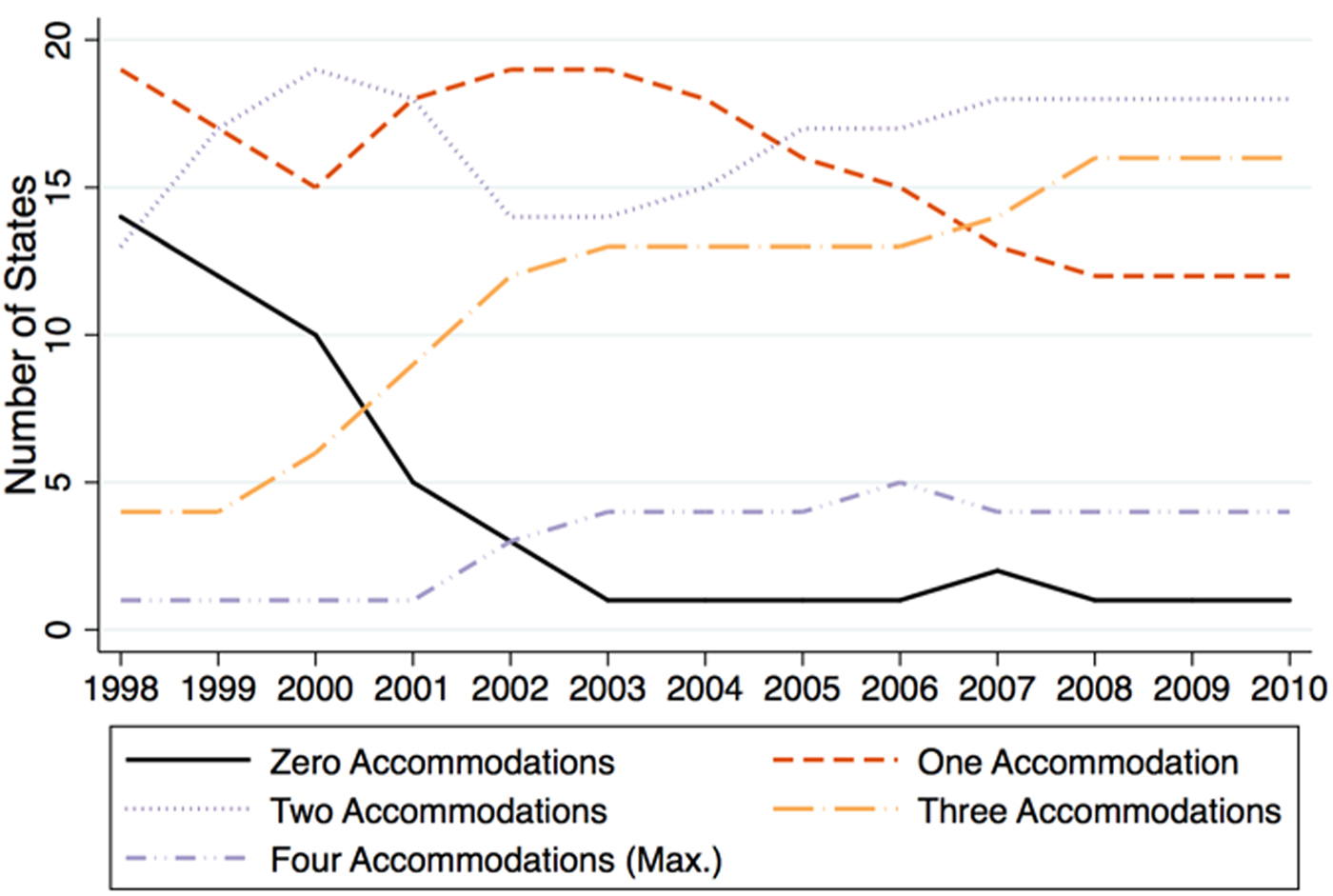

Overall, states became more generous towards recipients over time. In 1997, the year after welfare reform was passed, states allowed, on average, fewer than one policy accommodation for recipients who had experienced domestic violence. By 2010, states provided, on average, more than two accommodations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Domestic Violence Accommodations Adopted, 1997–2010

For all of these policies—time limit extensions and exemptions, activity exemptions, and child support exemptions—I anticipate that organizations advocating against domestic violence will be in favor of policies that accommodate the needs of recipients who have experienced abuse. Similarly, I expect feminist organizations to be supportive of more lenient policies, which leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis:

As domestic violence and feminist advocacy organizations comprise a greater percentage of a state's interest group population, the state will be more likely to adopt policy accommodations (activity exemptions, time limit exemptions and extensions, and child support reporting exemptions) for recipients who have experienced domestic violence.

DATA

The state welfare policies come from the Urban Institute's Welfare Rules Database (WRD). The WRD contains more than 1,000 variables covering welfare rules of all 50 states and the District of Columbia from 1996 to the present. The rules are continually updated, and state administrators are asked to verify their state's policies on a yearly basis. Using rules from 1997 to 2010, I created four binary variables to indicate whether a state makes an accommodation for a victim of domestic violence in the following areas: time limit exemption, time limit extension, activity requirement exemption, and child support enforcement exemption. All are coded so that 1 indicates a more lenient policy and a 0 indicates a stricter policy.

To collect a sample of advocacy organizations, I used Gale's Associations Unlimited.Footnote 2 This online data set contains information on more than 456,000 organizations at the international, national, state, and local levels. To create my data set of more than 11,000 organizations, I limited my search to regional, state, and local organizations and searched based on subject descriptor. I organize the groups into 19 categories; some of these categories include groups that are centered around an identity (separate categories for women's groups, African American groups, Hispanic groups, etc.), others around a policy issue (such as domestic violence groups and antipoverty groups), and still others represent a variety of business interests (e.g., chambers of commerce, agriculture groups, retail groups). The subject descriptors and examples of all 19 categories can be found in the supplementary appendix in the online version of this article.

The data set of interest groups is used to create two measures of interest group influence. Both measures come from the population ecology literature, which theorizes that the absolute number of interest groups in a state and the relative size of a given category of interest groups depends on the state's political and economic environment and affect policy outcomes (Gray and Lowery Reference Gray and Lowery1996). The first measure of influence is the total number of interest groups within a state, or the interest group density. I anticipate that the absolute size of a state's interest group population will affect its propensity to adopt more generous (or stringent) welfare rules. The second measure of influence is the diversity of interests, or “how numbers of organizations are distributed across some relevant typology of interests” (Gray and Lowery Reference Gray and Lowery1996). Diversity is calculated as the number of groups in a given category over the total number of interest groups within a state.

Stated simply, the interest groups within my dataset can be broken down into organizations in favor of changing a state's welfare program and those who prefer the status quo. The balance between these two sides should determine whether a state changes welfare rules as they concern recipients who have experienced domestic violence. Interest groups representing welfare recipients constitute a small percentage of interest groups within most states; as a result, politicians face little pressure to address their policy grievances. In contrast, business interests often make up a large proportion of a state's interest group population and are thus assumed to wield influence over policymakers (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Schlozman and Tierney Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986).

I do not anticipate that all interest groups within the state will be concerned with whether a state offers accommodations to welfare recipients who have experienced domestic violence. I primarily anticipate that domestic violence advocacy organizations and feminist organizations take an interest in these policies given the demographics of welfare recipients and the history of these groups advocating for similar policies, so I include the diversity measures for these two types of interest groups. I also include several other types of interest groups that may have a stake in state welfare policy.

The proportion of African American groups in a state is included because of the racialized perception of welfare recipients. Historically, there has been disagreement about whether African American organizations have adequately represented the interests of black women (West Reference West1981, 214). Issues of economic insecurity are of concern to African American groups, though, which may inspire them to get involved in welfare policy. A state that allows for activity exemptions and time limit extensions, for instance, may provide recipients with a better chance of achieving economic self-sufficiency than one without such accommodations.

The proportion of social welfare groups (groups that advocate on behalf of child welfare, poverty, and food scarcity) is also included because these organizations often directly interact with welfare recipients and individuals who have experienced domestic violence. One survey found that 75% of faith-based organizations served welfare recipients, with services ranging from food assistance to treatment for mental health and substance abuse (Allard Reference Allard2007, 317). Catholic groups in particular have been vocal in their opposition to some tenets of welfare reform (Cammissa and Manuel Reference Cammissa and Manuel2016, 14). I anticipate that service-based organizations will be in favor of welfare rules that make accommodations for recipients who have experienced domestic violence.

Social conservative groups, such as pro-life organizations and groups promoting traditional family values, are included in the analysis as well. Groups interested in maintaining traditional gender roles may be in favor of activity exemptions that keep women in the home but opposed to time limit exemptions or extensions for fear that it promotes welfare dependency. These organizations may also be in favor of requiring absent fathers to support their families through child support payments, which may conflict with allowing for exemptions to child support reporting requirements.

Finally, I include the proportion of industry groups in a state. Industry groups include those sectors that employ a large number of current or former welfare recipients (agriculture, construction, food and beverage, and retail) (Parrott Reference Parrott1998). Industries that rely on low-wage labor may be opposed to more flexible welfare policies because they keep recipients out of work; for instance, if a woman experiencing domestic violence is granted an activity exemption, she does not have to find a job (Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008). Similarly, if she is granted a time limit extension, she can delay her return to the labor force.

Measuring interest group density and diversity is one way of gauging interest group influence, and it comes with both advantages and disadvantages. As Lowery (Reference Lowery2013) notes, researchers have identified influence in several ways, including focusing on who possesses the resources that should enable the exercise of power, who has the reputation for being powerful, and who “wins” on a particular policy decision. Regardless of the approach taken, however, the majority of interest group research captures only “a snapshot of influence” (Lowery Reference Lowery2013, 7).

One problem in defining influence is that we do not know what would have happened in the absence of lobbying. In studying state adoption of the FVO, however, an absence of organizations lobbying on behalf of domestic violence survivors would have resulted in no policy accommodations. For states that have adopted at least one FVO provision, we may assume that some interest was lobbying for a change from the status quo. It is also possible, however, that an interest group lobbied on behalf of the status quo (not adopting the FVO). In this case, a success for that organization—an indicator of their influence—would show up as a lack of change in the data. Non-adoption of the FVO may not indicate the lack of influence among organizations lobbying for policy changes but perhaps a greater influence of those who want to maintain the status quo.

Interest group density and diversity standardize the influence of interest groups; the influence of an organization with an engaged membership is deemed equal to the influence of an organization that exists in name only. In this sense, the measure overlooks the importance of mobilization efforts and organization effectiveness; these influences are better captured through case studies. By using measures of density and diversity, however, there is also less emphasis on the role of money in lobbying. Within this model, a number of smaller grassroots organizations can theoretically place similar amounts of pressure on policymakers as one well-funded interest group.

Focusing on a state's interest group population also does not account for the anticipated reactions of interest groups to change in public policy. As Lowery (Reference Lowery2013, 6) notes, organized interests stake their positions in anticipation of the reactions of those being lobbied. Similarly, the actor being influenced—in this case, state policy makers—takes an initial stance in anticipation of the lobbying of the organized interest. As a result, it becomes difficult to parse out the sincere preferences of the actors. There are limitations to this research design, but it also provides for a greater understanding of influence because it utilizes the variation in the 50 states and the federal guidelines that act as a type of counterfactual.

Controls

Aside from the influence of interest groups, there are a number of other political, economic, and demographic variables that may account for variation in states’ implementation of policies towards survivors of domestic violence. I include several control variables found to be significant in previous welfare literature, including a state's poverty level, unemployment rate, and the black percentage of the state population (Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Neubeck and Cazenave Reference Neubeck and Cazenave2001; Sparks Reference Sparks, Schram, Soss and Fording2003).

Politically, the expansion of welfare policy is traditionally associated with the Democratic Party (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Mink Reference Mink1998). A dummy variable captures whether the state's governor is Democratic, and another measure is included to indicate party control of the legislature (1 = both houses are Democratic, 0.5 = one house is Democratic, 0 = neither house is Democratic). Past research has also shown that in states with greater women's representation, welfare policies tend to be more generous (Cowell-Meyers and Langbein Reference Cowell-Meyers and Langbein2009; Reingold and Smith Reference Reingold and Smith2012), in part because female representatives are more likely to introduce legislation on welfare than their male counterparts (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Swers Reference Swers2002). Congresswomen were heavily involved in the passage of VAWA; I expect female state legislators to be similarly involved in measures related to domestic violence (Stolz Reference Stolz1999). The percentage of the legislature that is female serves as a measure of descriptive representation.

I also control for the policies of the state's neighbors, measured as the mean value of the bordering states on the policy. The “race to the bottom theory,” as it is known, assumes that welfare recipients will move to the state with the most generous welfare benefits. Policy makers are compelled to make their programs more restrictive to prevent the state from becoming a welfare “magnet” (Bailey and Rom Reference Bailey and Rom2004; Berry, Fording, and Hanson Reference Berry, Fording and Hanson2003). Therefore, states whose neighbors choose not to implement parts of the FVO may do the same.

When looking at individual rules, it is important to recognize the context of the entire program. For that, I created indices capturing the generosity of a state's activity exemptions, and time limit exemptions and extensions.Footnote 3 States that grant time limit exemptions or extensions for domestic violence survivors offer significantly more time limit exemptions or extensions overall than states without domestic violence time limit exemptions and extensions. Moreover, states that exempt domestic violence survivors from work requirements offer significantly more activity exemptions than states without domestic violence activity exemptions. This suggests that some of the decision to grant an exemption to survivors of domestic violence may be based less on the FVO and more on the overall flexibility of the state's welfare program.

A similar measure captures the generosity of a state's child support. Cooperation with child support enforcement takes on a different meaning in every state, from requiring that recipients identify and provide information about the absent parent to establishing paternity to appearing as a witness at hearings related to child support enforcement. I compiled an index of the nine most common requirements (see Table A2 in the online appendix) as a measure of the rigor of a state's child support enforcement; on average, states have 6.5 requirements. Massachusetts has the fewest number of requirements, with only two, while Wyoming and Iowa use all nine requirements. This index is reverse coded so that higher values indicate a more lenient policy.

Qualitative Case Studies

To supplement the quantitative analysis of the relationship between welfare rules and a state's interest group community and capture some of this nuance, I compare the legislative histories of Connecticut and New Jersey. In many ways, the states are similar; between 1997 and 2010, both states had interest group populations just above the median (New Jersey ranked 19th and Connecticut ranked 22nd), and within their interest group populations, there were few organizations specifically devoted to domestic violence. Politically, both states were among the most liberal states (in the top 20%) as measured by citizen ideology. Throughout the entire time period, Connecticut had a Democratic legislature and a Republican governor, while in New Jersey, Republicans controlled both branches of government until the early 2000s, when the Democrats took control.

The states vary in their approach to welfare rules for recipients who have experienced domestic violence. While both states exempt recipients from child support requirements if they have experienced domestic violence, Connecticut did not exempt recipients from activities or time limits between 1997 and 2010. In contrast, after 2001, New Jersey provided all four accommodations for domestic violence survivors. What explains this variation?

Through the analysis of state legislative hearing testimony, I am able to address many of the nuances overlooked in the quantitative measures, such as whether one well-organized and mobilized group is exerting the same (or greater) level of pressure as several smaller groups. Second, measures of interest group density and diversity assume that each group in the category is advocating for a given policy, while the case studies provide evidence of who actually lobbied policy makers. While a domestic violence advocacy group may be the most obvious group to lobby on welfare rules as they pertain to recipients who have experienced domestic violence, interest groups have limited money and room on their agenda and may be forced to choose which policies are most important to address. Finally, these quantitative measures do not provide any insight into how interest groups convey their message. The numbers cannot speak to who is active in the organization (are they welfare recipients themselves, or others representing the interests of welfare recipients?) or how the message is framed. Examining the histories of Connecticut and New Jersey confronts these assumptions.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

To test whether states with more domestic violence advocacy organizations are more likely to implement FVO policies, I run logistic regressions on each dependent variable (the welfare rule). I include the interest group measures and control variables mentioned earlier, as well as year dummy variables. I also use robust clustered standard errors by state to control for correlated errors within a state. Prior to analyzing the multivariate results, though, I consider the bivariate relationship between the welfare rules and independent variables of interest.

Difference in means tests show that states adopting welfare rules to accommodate recipients who have experienced domestic violence have significantly more women in the legislature and a greater proportion of feminist organizations within the interest group community (see Table 1). Aligning with my expectations, states that allow for activity and time limit exemptions have, on average, a higher proportion of feminist organizations in their interest group population than states without the accommodations. States that provide child support and time limit exemptions to recipients who have experienced domestic violence also have, on average, a greater proportion of women in the state legislature than states without those exemptions. Running against my expectations, however, states with child support and activity exemptions have a smaller percentage of domestic violence organizations in the state interest group population than states without the exemptions. The following multivariate analysis provides greater detail into what may be driving these results.

Table 1. Bivariate relationship between variables of interest

Notes: A plus sign indicates that the state allowing the accommodation has a significantly greater percentage of feminist or domestic violence organizations or women in the legislature; a minus sign indicates that the state allowing the accommodation has a significantly lower percentage of organizations or women in the legislature.

Family Violence Option Results

Table 2 presents the full multivariate results. The four columns show the models predicting FVO provisions. Overall, there is no consistent pattern showing that an increase in the proportion of domestic violence or feminist organizations within a state leads to more policy accommodations for welfare recipients who have experienced domestic violence. Among FVO policies, the proportion of domestic violence groups in a state is only significantly related to the state's child support exemption, and that relationship is negative—an increase in the proportion of domestic violence groups decreases the likelihood that a state will allow a child support exemption.

Table 2. Logistic regression results

Notes: Logistic regression estimates are reported, along with clustered standard errors (state is the cluster). States excluded are Alaska, Hawaii, and Nebraska. Year dummy variables (1997–2010) are included but not reported.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05.

Even though the relationship between the proportion of domestic violence organizations in a state and the state's adoption of FVO policies does not confirm my hypothesis, testimony suggests that domestic violence advocates do speak on behalf of welfare recipients. Barbara Price of the New Jersey Coalition for Battered Women explained to the New Jersey Assembly's Policy and Regulatory Oversight Committee in 2002 the necessity for activity exemptions. Leaving an abusive situation, Price argued, could impede a woman's entry into the labor force because women are sometimes “forced to leave their job because their batterer continues to harass them at work.”Footnote 4 Without an activity exemption, a woman experiencing abuse may be forced back into an abusive situation after losing her TANF benefits because of “noncompliance” with activity requirements.

The proportion of feminist groups in a state's interest group population is not significantly related to the state's likelihood of adopting a child support exemption, time limit exemption, or extension for recipients who have experienced domestic violence, going against my expectations. Adopting an activity exemption, however, is positively related to the proportion of feminist groups. Joan Pennington from the Women's Law Project in Mercer County testified before the New Jersey Task Force on Domestic Violence in 1998. Describing her experience prior to welfare reform, she said, “Three times I left and three times I was told by the local welfare agency that they weren't going to support me and my children—to go back to my husband.”Footnote 5 The public assistance she eventually received provided the financial stability necessary to continue her education and start a career in advocacy.

States are significantly more likely to exempt recipients from activity requirements and allow for time limit extensions as the proportion of socially conservative groups in the state increases, though social conservative groups do not appear in the legislative hearings in New Jersey and Connecticut. An activity exemption may allow a mother to stay home with her children instead of seeking work, which aligns with the traditional family values favored by socially conservative groups. These socially conservative organizations may also be in favor of extending time limits because a family leaving an abusive situation may need additional time to become economically self-sufficient. Social conservatives may see the welfare state as a net gain if providing benefits past the time limit prevents the breakdown of a family.

States are also more likely to allow for time limit extensions as the proportion of social welfare organizations increases. Candida Flores, director of the Empowering People for Success Program, demonstrated the importance of these organizations in her testimony before the Connecticut Human Services and Select Committee on Children in 2004. She told legislators that the Empowering People for Success program “assists current and former temporary assistance recipients to achieve self-sufficiency” and has “served approximately 10,000 families” since 1997.Footnote 6 While Flores did not advocate for the state to adopt a specific welfare rule, she did ask policy makers to consider the barriers many recipients face:

[Recipients] come to us with a multiplicity of barriers that prevent them from finding and maintaining employment. … It is not uncommon to see a family facing domestic violence, substance abuse, transportation, housing, and child care issues all at the same time.Footnote 7

Organizations that provide low-income families with services and resources may advocate for more generous welfare rules because they are more familiar with the daily struggles of welfare recipients. Furthermore, a stronger social safety net relieves some of the financial burden for charitable groups.

Aside from interest groups, the relative generosity of a state's welfare policy is significant in predicting whether a state will adopt a more generous policy towards recipients who have experience domestic violence. A state that grants more activity exemptions is more likely to grant an activity exemption for those who are dealing with domestic violence. States that provide more time limit extensions and exemptions are more likely to extend these offers to those affected by domestic violence. All of these findings suggest a state's decision to adopt the FVO is not made in isolation from the rest of the program; a state willing to accommodate recipients who have experienced domestic violence will be willing to accommodate those facing other challenges.

Neighboring state policy appears to have a limited effect on a state's decision to adopt provisions of the FVO. States are less likely to adopt an activity exemption if their neighbors have adopted the exemption. States are no less likely, however, to allow for time limit exemptions and extensions or child support reporting exemptions when their neighbors allow for the exemption. A high unemployment rate increases the likelihood that a state will adopt activity exemptions. In a state with higher unemployment, policy makers may acknowledge the difficulty in meeting work requirements, especially for those with additional barriers to employment.

After controlling for other variables, the political environment of the state appears to be largely irrelevant to a state's welfare rules regarding survivors of domestic violence. A state with a Democratic governor is not more likely to produce more generous policy. States with a Democratic legislature are more likely to allow for activity exemptions for recipients who have experienced domestic violence, but there is no significant relationship between other FVO rules and party control of the legislature.Footnote 8 Both the PRWORA and VAWA received broad bipartisan support in Congress, which may explain why party control is not significant in many of the models. During the national welfare debate, both Democrats and Republicans came out in favor of ending the “culture of dependency” associated with welfare; similarly, state legislators from both sides of the aisle may be interested in welfare reform. Moreover, survivors of domestic violence are not the “typical” welfare recipients, and thus policy makers of all political affiliations may see survivors of domestic violence as more deserving of government assistance.

In the multivariate analysis, greater women's representation is no longer significantly related to more generous policy for survivors of domestic violence. Rather than indicate that women in government do not matter, these results raise questions about whether women's representation with regard to welfare policy is less about critical mass (the number of women in the legislature) and more about critical actors (what specific actors do) (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009). In Connecticut, for instance, Mary Ann Handler, chair of the Human Services Committee, used her position to ask how child support enforcement affected women and children who had left abusive environments:

So often with the break up of marriages, and with marriages that end up with women in welfare or needing aid, there is also an issue of domestic violence. … Is there built into this system … a method to protect the women, usually, and her children from domestic violence, from further violence, which might result as, which might be the result of an effort to collect back payments.Footnote 9

In New Jersey, Assemblywoman Rose Marie Heck led the state Task Force on Domestic Violence. In one of several hearings held by the task force, Heck lamented, “Look at all the media attention we are getting. None. This is a major problem, and we need communication to the public at large, but the media is not taking us very seriously yet.”Footnote 10 At other points in the hearing, Heck mentioned organizing a field trip to a pilot counseling program within the state. Heck used her position as chair to raise awareness about the issue of domestic violence and making sure successful programs were recognized for their progress, while Handley's questions during a child support hearing gave evidence to her concern for the most marginalized citizens.

New Jersey and Connecticut provide evidence of representation through female legislators and feminist and domestic violence advocacy organizations. There is little evidence to suggest, however, that minority representation played a large role in the crafting of welfare policy.Footnote 11 The models show that the proportion of African American groups in a state is not significantly related to policy accommodations for survivors of domestic violence, and the hearings in New Jersey and Connecticut provide no evidence of African American organizations lobbying on behalf of welfare recipients. This aligns with previous research that has shown reluctance from African American organizations to align themselves with welfare recipients (Reese Reference Reese2005). Moreover, the leadership of the New Jersey and Connecticut assemblies and the committees responsible for policy related to domestic violence and welfare had few minority members. Reingold and Smith (Reference Reingold and Smith2012) note that some minority legislators were hesitant to entrust domestic violence initiatives to the states given people of color's experiences with state violence. Future research should explore how representatives address these topics in legislatures with greater minority representation.

An Unmet Need

Independent of providing exemptions or extensions to TANF recipients with domestic violence waivers, advocates in both New Jersey and Connecticut lobbied the legislatures to focus more attention on screening and assessment. Heidi Gold of the Poverty Research Institute of Legal Services of New Jersey expressed her concerns when testifying before the New Jersey Assembly's Health and Human Services Committee in 2002. Based on her experience as a social worker, she observed that many TANF recipients “have been victims of child abuse and/or domestic violence and were in deep pain that has lasted all of their lives.” In a study conducted by her organization, 42% of long-term TANF recipients surveyed reported suffering from major depression, and more than one in 10 women reported that their mental health made working difficult. Gold had the following recommendations for the Assembly:

First, a full and comprehensive assessment, including issues of physical and mental health, should be made prior to sanction or termination from welfare to determine whether a person's physical or mental health was the barrier to participation in the Work First New Jersey Program. Two, welfare grant levels must be raised.Footnote 12

In Connecticut, the lack of financial support both for TANF recipients and for the community organizations providing social services repeatedly came up in legislative testimony. Lucy Potter of Hartford Legal Assistants criticized the state for pushing recipients with various personal barriers, including domestic violence, off the welfare rolls too soon. Testifying before the Human Services Committee in 2001, she said,

The long and short of it is that it's really unreasonable for the Governor to tell TFA [Transitional Family Assistance] recipients that as of October 2001 you should have been able to get your act together when the state has done nothing for these people despite having the resources to do it. … TANF funding was there to do this, unlike other states we have not chosen to do that, and it's incredibly unfair to now tell those people that their time is up.Footnote 13

Cheryl Kohler, an attorney at Connecticut Legal Services, spoke of her experience working with victims of domestic violence before the Human Services Committee in 2003. Kohler advocated for up-front assessments of recipients, which she described as “essential to finding out why these people are not succeeding in programs.” While the legislators were focused on physical barriers to employment, Kohler said,

I'd like to bring to your attention that there's multitudes of other barriers. The sexual abuse. The domestic violence. Substance abuse. … By identifying and addressing barriers early in the TFA process, individuals could be sent to programs that would help them successfully comply and help them to remove those barriers to get out and get a job. Right now, they get to go through the whole system without these barriers being identified and they're left with nothing.Footnote 14

In many cases, however, domestic violence organizations are asking the legislature to not only consider the financial needs of those who have been affected by domestic violence but also to protect the funding for those that provide services. At a 2009 Appropriations Committee hearing, Linda Blozie from the Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence asked the legislature to “oppose the Governor's mitigation package as it is because it will affect domestic violence services.” Even if the deficit mitigation plan did not immediately cut funding to domestic violence shelters, other funding cuts “are also vital services that most domestic violence victims and survivors seek out in Connecticut,” according to Blozie.Footnote 15 Domestic violence organizations in Connecticut may have little time to advocate on behalf of domestic violence survivors receiving TANF if there is constant conflict over funding for social services.

Even members of the bureaucracy testified to the necessity of increased funding. Speaking before the Human Services Committee in 2004, Belinda May, an eligibility supervisor in the Connecticut State Department of Social Services, expressed concern about staff shortages. Staff did not have sufficient time to “identify client barriers to employment, mental health issues, substance abuse problem and domestic violence issues”; as a result, “the client suffers and sometimes falls through the cracks.” According to May, the “cracks are becoming craters.”Footnote 16 Waivers from particular TANF rules made little difference if recipients were not given the opportunity to disclose their personal barriers. Connecticut's less generous FVO policies provide an example of how social services suffer from recurring budget problems (Dautrich, Robbins, and Simonsen Reference Dautrich, Robbins and Simonsen2010).

CONCLUSION

Welfare policy is of great interest to those studying race, gender, and state politics. Yet in most of that research, welfare (usually referring to AFDC or TANF) is generalized in both the analysis of the policy rules and the recipients that it affects. Key to understanding state welfare programs is recognizing how state discretion allows for states to recognize the individual challenges and barriers of welfare recipients.

Welfare recipients are marginalized in any number of ways. By definition, they are low-income, and thus are less likely to participate in politics, form organizations, and have their interests expressed by those in power. The stereotypical welfare recipient is a woman of color who is lazy, promiscuous, and dependent on the state. A large percentage of welfare recipients have also experienced domestic violence, which only serves to make them more vulnerable. Unlike the stereotype of the “welfare queen,” though, sympathy is more easily garnered for welfare recipients who are fleeing abuse and trying to restart their lives.

In seeking to explain why states have adopted such a wide variety of welfare programs, scholars have turned to theories about party control, descriptive representation, and the persistence of racism in policy making. These explanations fail to provide a reason why some states are more likely to adopt provisions of the FVO than others. This may largely be explained by the unique position of the TANF recipient who has survived domestic violence. She is at once part of a highly racialized population that is deemed undeserving of government help while simultaneously portraying a level of helplessness that calls for government intervention. The bipartisan support behind welfare reform and VAWA weakens the argument that in states with Democratic legislatures and governors there are more generous policies. My analysis shows that women's representation also does not have a strong relationship with more generous welfare policy, raising questions about whether critical mass or critical actors are more important in representing the interests of women. Finally, there is no significant relationship between the racial composition of a state and its adoption of FVO provisions, which suggest that policy makers may rely less on racial stereotypes when designing policies for those who have experienced domestic violence. Because survivors of domestic violence are a particularly sympathetic subset of welfare recipients, female and minority legislators may not be as essential in the adoption of policy accommodations for these recipients. Descriptive representation may play a larger role, however, when policy makers are forced to confront the stereotype of the “undeserving” welfare recipient.

Leaving behind these traditional explanations for state variation in welfare policy, what caused some states to adopt these measures and others to forgo the FVO? The results of my quantitative analysis show that the proportion of domestic violence advocacy organizations in a state's interest group community was not significantly related to whether a state made accommodations for survivors of domestic violence. The case studies suggest, however, that domestic violence organizations were lobbying policy makers to address the needs of these welfare recipients. In New Jersey, these organizations appear to have been effective in their advocacy, while in Connecticut, domestic violence organizations frequently had to lobby for basic funding at the expense of focusing on the needs of recipients. Interest groups have limited financial and human resources. When groups are struggling to remain open, they may choose to use their appearances in front of policy makers to make the case for more funding, instead of lobbying for more generous policies of those they serve. In this respect, the diversity and density measures of interest group influence fall short, because little is known about the resources available to interest groups and all interest groups are assumed to have equal pull with legislators. Large-n studies cannot answer the question of how individual organizations affect change while balancing other organizational needs. These questions will need to be answered through case studies and more in-depth analysis of individual organizations.

Domestic violence advocacy organizations are not the only force at work in the implementation of these policies though. An increased proportion of feminist organizations in the states increased the likelihood that a state would provide activity exemptions to recipients with domestic violence waivers. Furthermore, the proportion of social conservative organizations within a state was positively related to the likelihood of a state adopting an activity exemption and time limit extension for survivors of domestic violence. Advocacy organizations cannot create policy on their own, however, so future research should look into how outside groups interact with inside actors to achieve their policy goals.

Finally, the overall generosity of a state's welfare program heavily influences whether special accommodations are made for survivors of domestic violence. A state that is committed to addressing the individual obstacles of its welfare recipients will not only provide exemptions and extensions for those who have experienced domestic violence but also extend those same accommodations to others depending on their needs. While this article has focused on policy accommodations for those who have experienced domestic violence, there are many other subgroups within TANF: minor parents, those caring for disabled children or other family members, or those in need of mental health or rehabilitation services, just to name a few. Future research on welfare policy should consider that while TANF may have been created at the federal level as a “one-size-fits-all” policy, the great discretion granted to states allows for states to recognize and respond to the needs of individual recipients.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X18000429