INTRODUCTION

Across much of Africa, corruption has become so deeply entrenched and widespread that African governments are often seen to be under the influence of venal politicians and officials (Bayart et al. Reference Bayart, Ellis and Hibou1999; Chabal & Daloz Reference Chabal and Daloz1999; Yeboah-Assiamah et al. Reference Yeboah-Assiamah, Asamoah, Bawole and Musah-Surugu2016). Anti-corruption law enforcement, in turn, suffers from the same problems affecting African governments at large: it is overwhelmed, underfunded and compromised by political influence. Therefore, its capacity to curb corruption has been questioned (Kpundeh Reference Kpundeh, Kpundeh and Hors1998; Riley Reference Riley1998; Heilbrunn Reference Heilbrunn2004; Tangri & Mwenda Reference Tangri and Mwenda2006; Lawson Reference Lawson2009; Persson et al. Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2012; Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa 2017). Perhaps because of these low expectations, scant scholarly attention has been paid to anti-corruption law enforcement's potential for deterrence in Africa. In general, African criminal justice systems since independence have only attracted limited scholarly attention. Among the principal studies covering aspects of law enforcement in Africa are Coldham (Reference Coldham2000), Brown & Sriram (Reference Brown and Lekha Sriram2012) on Kenya, Comaroff & Comaroff (Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2004) and Plessis & Louw (Reference Plessis and Louw2005) on South Africa, Robins (Reference Robins2009) on Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia, and Ng'ong’ola (Reference Ng'ong’ola1988) on Malawi, but none of them examines law enforcement's impact on corruption deterrence.

This article addresses this lacuna. By drawing on mixed-methods evidence from Malawi, we aim to understand law enforcement's potential for corruption deterrence in spite of the weak legal framework, lack of resources, frequent delays, selective justice and uneven sentencing (Kanyongolo Reference Kanyongolo2006). We offer a novel perspective on anti-corruption law enforcement in Africa by probing perceptions of deterrence from the perspective of serving government officials. Considering deterrence perceptions among government officials enables us to understand how law enforcement efforts shift perspectives of the risks of breaking the law (Williams & Hawkins Reference Williams and Hawkins1986; Paternoster Reference Paternoster2010).

The article focuses on the impact of the law enforcement response to a large-scale corruption scandal in Malawi, known as ‘Cashgate’. Since 2013, the country has been in the throes of this scandal: the centrally organised theft of government funds characterised by large amounts of cash discovered in the possession of government officials, politicians and businesspeople.

The research combines the findings of two methodologies: (1) a qualitative study employing in-depth semi-structured interviews with 51 officials in key positions between November 2016 and January 2017 and follow-up visits to Malawi in May and August 2019, and (2) a quantitative conjoint experiment with 524 randomly selected government officials across Malawi's three regions in January and February 2017. In line with what Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite1993) calls an ‘integrated strategy’ this study combines quantitative and qualitative research in a mixed-methods approach. The quantitative conjoint experiment provides a causal test of how various aspects of the law enforcement response shape officials’ perceptions of the potential for deterrence. While precise, this methodology is abstract, asking officials to consider hypothetical situations rather than their current environment. To complement this test, the qualitative research provides a context-specific and nuanced understanding of the mechanisms and dynamics underpinning the effect of law enforcement on corruption deterrence in the context of the Cashgate scandal. In combination, we use these two methodologies to assess whether government officials perceive, based on their insider knowledge, that the response of law enforcement to corruption can deter future corruption.

Our research shows that Malawian government officials perceive that law enforcement can deter future corruption, even in spite of gaps in the legal framework, insufficient resources available, frequent delays, threat of selective justice and inconsistent sentencing. Drawing on the mixed-methods evidence, we find that certainty and swiftness in detecting and punishing corruption are critical in maximising law enforcement's potential for corruption deterrence. While encouraging for those involved in anti-corruption efforts, it should be noted that our study represents the perceptions of one set of officials at a particular point in time. Deterrence depends on sustained law enforcement. As soon as certainty and swiftness of punishment are perceived to decrease, any deterrent effect is likely to diminish.

The article proceeds as follows. First, it examines the enabling and inhibiting factors shaping law enforcement in Malawi and presents the methodologies employed by the study. The analysis is split in two sections. The first one presents the survey findings on the extent of corruption in the Malawi civil service. The second section examines in detail the findings with regard to the three elements of deterrence – certainty, swiftness and severity of the law enforcement response – from the perspective of the government officials in Malawi.

THE MALAWI CONTEXT

In Malawi, the growth of corruption is a relatively recent phenomenon that has been linked to the introduction of multiparty representative democracy and the liberalisation of the economy during the mid-1990s (Anders Reference Anders2010). The need for campaign funds and the weakening discipline of government employees who exploited the newly available economic opportunities have fuelled the increase in corrupt practices (Anders Reference Anders2010: 124–5). An important influence on the spread of political corruption in particular has been the weak regulatory framework for political party financing, as Dulani (Reference Dulani and Amundsen2019) shows. Since the 1990s, there have been a number of high-level corruption scandals involving ministers and directors of parastatal companies (Anders Reference Anders2010: 122–5) but in contrast to Cashgate, these scandals remained limited to specific ministries and did not trigger sustained law enforcement efforts.

The Cashgate scandal is remarkable for two reasons. On the one hand, it was the biggest corruption scandal ever uncovered in MalawiFootnote 1 and, on the other hand, the scale of the law enforcement response was unprecedented. The latter was mainly due to the political landscape at the end of 2013 that created a favourable climate for sustained law enforcement efforts. It is estimated that within a six-month period between April and September 2013 over US$32 million were stolen and it is possible that more than US$280 million have been stolen since 2009 (Baker Tilly Reference Tilly2014; RSM 2016). The large-scale theft of public funds was discovered in September 2013 when the country was in the middle of the run-up to the May 2014 elections. As the extent of the corruption racket was revealed, President Joyce Banda ordered a forensic audit, which was funded by the British government (Baker Tilly Reference Tilly2014). By 2014, one hundred suspects had been arrested (the overwhelming majority were released on bail).

The forensic report on Cashgate by the auditing firm Baker Tilly (Reference Tilly2014) covers ‘the extraction of ‘cash’ (with the main currency being that of Malawi Kwacha) using systematic money laundering activities through commercial organizations’ (Baker Tilly Reference Tilly2014: 4). The report confirms that more than 13 billion Malawi Kwacha (~US$32 million) were stolen over a six-month period between April 2013 and end of September 2013. Drawing on the forensic audit (Baker Tilly Reference Tilly2014) and the interviews we conducted in the qualitative study, our study differentiates three types of corruption. The first type is centrally organised theft of government funds, largely facilitated via the Integrated Financial Management Information System (IFMIS) and organised by a relatively coherent group in key positions. The second type is high-level procurement fraud involving ‘overvalued and high value transactions, payment for goods not received and funding transferred internationally’ (Baker Tilly Reference Tilly2014: 5), which appears to be less centralised, but tends to include a number of networks of senior managers in strategic relationships with junior staff – especially accountants and IT-staff. These two types of high-level corruption are differentiated from smaller, localised corruption rackets mainly involving senior and mid-level managers (and sometimes elected councillors) at the district level focusing on bribery, theft of government property as well as allowance and procurement fraud.

At the end of May 2014, Joyce Banda was succeeded in office by Arthur Peter Mutharika and the law enforcement effort gathered steam, resulting in the arrest of dozens of suspects, far-reaching criminal investigations and a series of high-profile criminal trials. Thirteen cases had been concluded at the time of writing in April 2020. The first judgment was handed down against the Principal Secretary in the Ministry of Tourism, who was sentenced in October 2014 to three years in prison for money laundering. Only a month later, an accounts assistant who had been found with US$66,000 in cash was sentenced to nine years in prison. Several other government officials were also found guilty of money-laundering and received prison sentences. One of them, an Assistant Director in the Ministry of Tourism, was sentenced to imprisonment for seven years. In September 2015, a wealthy businessman and functionary in Joyce Banda's People's Party was sentenced to 11 years in prison. In a related case, the Minister of Justice was found guilty of plotting the murder of the Budget Director in the Ministry of Finance and was sentenced to 13 years in prison. At the time of writing, the Budget Director is facing trial for money laundering and theft with 17 co-accused including the former Accountant General and other government officials.

The events described above highlight several factors that created favourable conditions for the sustained law enforcement effort. The Cashgate scandal hit the headlines during the election campaign for the May 2014 elections and President Banda was compelled to take action to minimise the fallout for her bid for the presidency. By commissioning the forensic audit and calling for prosecutions she clearly sought to distance herself from the scandal. The international development partners put Banda under considerable pressure by suspending budget support, which had severe consequences on the government budget. Faced with a massive cut in available funding in the midst of the election campaign (Malawi's government budget relies to a large extent on foreign development assistance) she had no other option than to take action. After Banda lost the elections, her successor exploited the opportunity to support the law enforcement efforts against individuals that were mainly associated with his predecessor. Malawi's development partners led by the UK and the EU continued to demand decisive action against corruption. They provided financial and logistical support to the law enforcement agencies that launched a large number of investigations and prosecutions.

Despite these enabling factors in favour of stronger law enforcement there have also been inhibiting factors at work. Malawi's legal framework is characterised by the coexistence of statutes dating back to the colonial period and more recent anti-corruption legislation. The layering of new laws such as the 1995 Corrupt Practices Act and the 2006 Money Laundering Act on top of colonial statutes mainly reproducing English law of the 1950s has not been matched by efforts to address inconsistencies, gaps and ambiguous provisions. This had direct effects on the prosecutions and trials targeting the perpetrators of the Cashgate corruption racket. Since the offences mainly concerned the unauthorised drawing of government cheques and money transfers to private banks, the prosecutors struggled to charge the accused with theft, which requires the perpetrator to take possession of property. Consequently, they mainly relied on money laundering charges, drawing on the untested 2006 Money Laundering Act. However, according to senior law enforcement officials we interviewed, this law ‘was not up to the task’ and it was indeed replaced in 2018 by the Financial Crimes Act. The inadequacies in the law became apparent when one of the main suspects of the Cashgate scandal, a government accountant, was acquitted on appeal. In 2015, the High Court in Lilongwe had sentenced the accountant to eight years in prison for theft and money laundering. In 2018, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction for theft. The conviction for money laundering, in turn, was also overturned because the Supreme Court judges considered theft as predicate offence for money laundering. Thus, without a conviction for theft the conviction for money laundering was void.

Further, law enforcement efforts in Malawi have been significantly affected by a lack of resources. A recent study (Chingaipe Reference Chingaipe2017) found that the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) is understaffed, especially in the prosecution and investigation departments which have significant staff shortages (Chingaipe Reference Chingaipe2017: 162–3). Another major factor affecting the agency's effectiveness is the lack of financial resources. According to the report, ‘the ACB faces acute resource constraints which [are] compounded by erratic funding’ (Chingaipe Reference Chingaipe2017: 154). The situation is similar at the other law enforcement agencies: The Fiscal and Fraud Unit, the Directorate of Public Prosecutions and the Financial Intelligence Authority are all understaffed and under-resourced.

Finally, prosecutions and trials have been hampered by frequent and sometimes lengthy delays. For example, the trial at the High Court in Lilongwe against 18 of the main suspects including the former Budget Director at the Ministry of Finance and the former Accountant General started in December 2015 and had not been concluded at the time of writing in April 2020. One of the main reasons for the slow progress were the frequent adjournments and the small number of sitting days per month. For example, in 2019, the court sat on only three days per month with months of adjournments in between. Similarly, of the initial 60 Cashgate-related cases in 2014, only 13 had been concluded by 2019. About 40 cases never made it to the trial stage. For instance, in August 2019 the Magistrate's Court in Lilongwe ordered the Anti-Corruption Bureau to appear in court to explain why 14 accused charged with Cashgate-related offenses should not be discharged. These accused including high-ranking officials and the former Inspector General of the police were heard in court for a plea in October 2014 but after almost five years the trials had not even started. The backlog of cases and frequent delays are by no means unique to the Cashgate prosecutions. They affect all aspects of the justice system in Malawi (Kanyongolo Reference Kanyongolo2006: 101, 140–1).

METHODS EMPLOYED IN THE STUDY

The research builds on the in-depth anthropological study on the Malawi civil service by Anders (Reference Anders, Blundo and Lemeur2009, Reference Anders2010) and the mixed-methods research by Seim (Reference Seim2014) and Robinson & Seim (Reference Robinson and Seim2018) focusing on motivations, rationalisations and practices of Malawian public officials who perpetrate corruption. The secretive and illegal nature of corruption is a considerable barrier to rigorous empirical research on this topic (Blundo Reference Blundo, Nuijten and Anders2007; Anders Reference Anders, Blundo and Lemeur2009). The researchers addressed these challenges by designing a mixed-methods research approach that factors in the sensitive nature of the information sought and triangulates the different data sources to understand the potential for corruption deterrence in Malawi comprehensively.

The sociocultural context of Malawi provides a compelling environment to examine the effect of law enforcement on government officials’ perception of deterrence. As in the rest of Africa, the modern state in Malawi is a product of the colonial encounter resulting in a disconnect between the moral values promoted by the state apparatus and prevalent moral values in society (Ekeh Reference Ekeh1975). In Malawi, as in other African societies (Olivier de Sardan Reference Olivier de Sardan1999; Blundo & Olivier de Sardan Reference Blundo and Olivier de Sardan2006; Smith Reference Smith2008), there is a lack of deeply entrenched moral values and social sanctions that compel compliance with the law of the modern state (Anders Reference Anders, Blundo and Lemeur2009). In contrast, there is a heavy emphasis on the norm of sharing with others, a social obligation felt in particular by the more affluent members of society who are expected to share their wealth. Specifically with regard to Cashgate, it seems those who were involved in the theft of government funds often made a point of being generous to improve their social standing in the community. These values and the lack of social sanctions lend support to the assumption that any perceived subjective deterrent effect can be mainly attributed to the impact of law enforcement.

The qualitative research consists of 51 interviews with government officials on Capital Hill, the area in Lilongwe where most of the government ministries are located, and key informants in the law enforcement agencies and the judiciary, conducted between 25 November 2016 and 12 January 2017. In addition, the qualitative research included observations and informal conversations at key sites relevant to Cashgate and two follow-up visits to Malawi in May and August of 2019. All interviews were semi-structured, allowing the interviewees to expand on issues or introduce themes they deemed important and enabling the researchers to adapt to specific topics that came up in conversation.Footnote 2

To determine the perception of government officials working with IFMIS, sampling specifically focused on controlling officers in senior management roles, the Common Accounting Service and junior accountants. Sampling covered most government ministries including the Office of the President and the Cabinet, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture.Footnote 3 Thanks to the personal introductions, assurances of anonymity and the team members’ familiarity with the Malawi context, the team was able to build rapport with the interviewees who were all willing to openly discuss the Cashgate scandal, corruption and the impact of the law enforcement response.Footnote 4

During each interview, the interviewer discussed the interviewee's understanding of the two key concepts employed by the study: corruption and deterrence. Across Africa, there are rich vernaculars of corruption and widely shared indigenous moral norms that justify corrupt practices by invoking social and moral obligations to kith and kin (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2001; Smith Reference Smith2001; Hasty Reference Hasty2005; Blundo & Olivier de Sardan Reference Blundo and Olivier de Sardan2006; Anders Reference Anders, Blundo and Lemeur2009). However, the existence of multiple moral discourses of corruption does not imply that government officials’ definition of corruption is at odds with the legal definition of corruption and corruption-related offences. Even though officials might justify some corrupt practices by invoking social and moral obligations, especially with regard to petty corruption (Anders Reference Anders, Blundo and Lemeur2009; Blundo & Olivier de Sardan Reference Blundo and Olivier de Sardan2006), they usually do not condone high-level corruption on moral grounds. This was confirmed by our study. No government official we interviewed offered a cultural interpretation of the high-level and centralised theft of government funds. In each interview the interviewer confirmed that deterrence referred to the omission of corrupt practices due to the fear of punishment. The interviews unpacked the concept by differentiating certainty, swiftness and severity of punishment.

A large-scale survey conducted in January and February of 2017 provided a test of causal relationships between dimensions of law enforcement and perceived corruption deterrence.Footnote 5 The survey was executed among a random sample of 524 government officials across Malawi. The survey sampled 444 government officials posted in the headquarters of government agencies in Lilongwe, Blantyre and Zomba, and 80 government officials posted in decentralised agencies in eight randomly selected districts: two districts in the Northern Region (Mzimba and Nkhata Bay), three districts in the Central Region (Mchinji, Salima and Ntcheu), and three districts in the Southern Region (Blantyre, Phalombe and Zomba).Footnote 6 This multi-level sampling strategy facilitates the comparison of corruption patterns and perceptions across centralised and decentralised government offices.Footnote 7

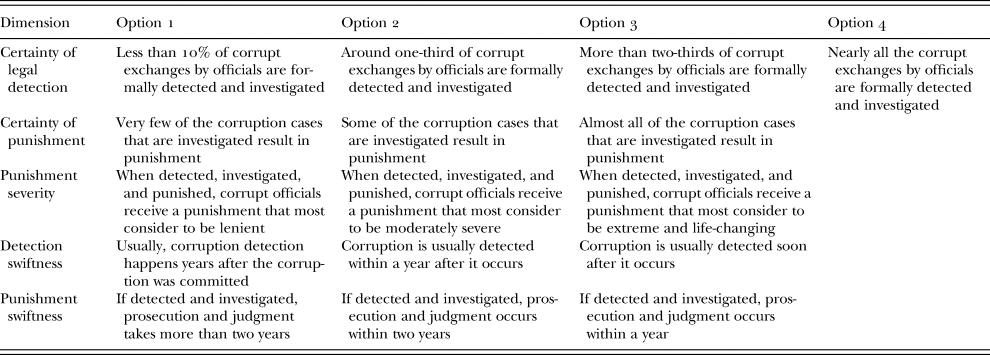

Embedded in the survey was a conjoint experiment to test how aspects of the law enforcement response affect officials’ perceptions of corruption deterrence. We followed the procedure laid out in Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2013) in designing and analysing the conjoint experiment. In such an experiment, the participant is asked to examine two hypothetical law enforcement environments (aka profiles) that differ along the law enforcement dimensions identified above as possible drivers of deterrence: the certainty and swiftness of detection and punishment, and punishment severity.Footnote 8 In this article, we focus on a subset of the dimensions varied in the conjoint experiment, presented in Table I, along with the text for the profile descriptions. In each profile, the description of each dimension was randomly selected from the options displayed in Table I.

Table I Conjoint experiment dimensions and values.

After examining the two environments, the respondent was asked to evaluate them on a set of outcomes: which one of the two environments would result in higher corruption, or harder working government officials, or a more respected judiciary, for example. Because each environment's descriptions of the dimensions are randomly selected from a set of options (see Table I), the researcher was able to empirically identify the causal effect (specifically, the average marginal component effect, or AMCE) of each dimension on the respondent's choice of one environment over the other.Footnote 9 In total, the conjoint experiment documented 17 outcomes that group into three areas: bureaucratic performance, accountability and the effectiveness of anti-corruption systems, though we focus only on a subset of the outcomes within bureaucratic performance in this article.Footnote 10

The conjoint experiment captured the respondents’ perceptions of what would happen in the hypothetical law enforcement environments presented to them, rather than their perceptions of what has actually happened in a real-world scenario (e.g. post-Cashgate). By adapting the features of the hypothetical law enforcement environments, the conjoint experiment is a more malleable method but is also more abstract, thereby providing a complement to the more concrete but also more context-specific interviews. Further, by disaggregating the analysis of the conjoint experiment according to salient characteristics of the government officials (e.g. level of seniority or type of role), we can assess patterns of corruption deterrence perceptions within different sub-groups. We include such sub-group analysis in the following two sections.

CORRUPTION IN GOVERNMENT AGENCIES: SURVEY RESULTS

While the primary goal of the survey was to probe perceptions of corruption deterrence, it also provided an opportunity to document patterns and trends in corruption pre- and post-Cashgate from the perspective of government officials in Malawi. This in-depth focus on the perceptions of government officials supplements previous surveys on corruption in Malawi by Chinsinga et al. (Reference Chinsinga, Dulani, Mvula and Chunga2014) and Chunga & Mazalale (Reference Chunga and Mazalale2017).

The officials in the survey estimated that the average corrupt official in their institution obtains 24% of his or her income from corruption.Footnote 11 Answers to this question are highly correlated with answers to a question asking respondents to estimate the percentage of officials in their institution who have engaged in corruption in the last year (correlation coefficient: 0.80, P = 0.0000). This suggests that highly corrupt institutions in terms of the proportion of officials involved are also highly corrupt in terms of the monetary impact. To understand the prevalence of various corrupt practices, officials were also asked whether they had committed various forms of corrupt acts in the six months preceding the interview. Three forms of corruption were examined: the acceptance of bribes, the issuance of false receipts, and the favouritism of friends and family in awarding them government contracts or jobs. These three questions represented the low-level, routinised corruption, the mid-level, more sophisticated corruption and the most organised and high-level corruption, respectively. Table II compiles the information provided by officials in response to direct questions about their own behaviour.

Table II Per cent of officials who acknowledged engaging in corruption.

On average, 28% of all officials accepted a bribe in the past six months (Table II, first column, first row). On average, 25% of officials stated they have falsified a document in order to pocket some funds (Table II, second column, first row). Finally, on average, 27% of the sampled officials have selected a friend or family member for a government job or contract (Table II, third column, first row).

These results were less pronounced among senior officials across all three types of corruption (Table II, second row). Non-HQ officials report higher rates of corruption than those in headquarters in terms of accepting bribes (representative of low-level corruption), falsifying documents (representative of mid-level corruption), and favouritism for family or friends in government jobs and contracts (representative of the high-level, organised corruption endemic in Cashgate) (Table II, fourth and fifth rows).Footnote 12 In other words, low-level government officials and those working outside of headquarters report higher rates of corruption. This should not come as a surprise as staff outside of the headquarters tend to have more interaction with members of the public who might be tempted to pay bribes. By contrast, bribery is less likely to occur in the ministerial headquarters, where officials have only limited interaction with the public. At the ministerial headquarters, it is more likely to find corruption requiring a high level of organisation such as Cashgate.

Another set of questions in the survey asked specifically about trends in corruption rates pre- and post-Cashgate. Eighty-five per cent of officials state that corruption in their institution had remained the same or increased since 2012 (immediately before Cashgate). This perception is consistent regardless of post, employer location or level in the public-sector hierarchy. While one interpretation of this finding is that the law enforcement efforts responding to Cashgate were unsuccessful, it is equally possible that these efforts simply ‘shone a light’ on corruption in Malawi such that the survey responses merely reflect the intensity of the public debate about corruption when actually it remained the same or even decreased. Unfortunately, the survey data do not allow us to adjudicate between these two plausible explanations, so this will remain an avenue for future research. In sum, the survey data indicate that corruption in Malawi is still prevalent after Cashgate. Probing the deterrent effect of the law enforcement response, we examine perceptions of deterrence among government officials.

PERCEPTIONS OF DETERRENCE

One important aspect of deterrence is publicity and communication (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1983: 6). Without knowledge of the sanctions and information about punishment meted out, no deterrent effect can be expected, as likely perpetrators need to be aware of the threat of punishment. Our research shows that government officials were well-informed about the extent of corruption and the law enforcement efforts. All interviewees stated that the perpetrators of Cashgate and other high-level corruption scandals knew that what they were doing was illegal and against regulations. As one of them put it: ‘They knew. People know the law. They know there are protocols. They know the three Ps: The Public Audit Act, the Public Finance Management Act and the Public Procurement Act.’ Another one pointed out that ‘there is no excuse’ as ‘in terms of government procedures everything is in black and white’.

The findings present a nuanced picture of government officials’ perceptions of the effect of the law enforcement efforts. The analysis of the 51 interviews of the qualitative study paints a detailed picture of the potential for corruption deterrence. According to 32 interviewees, the law enforcement response to Cashgate had a deterrent effect on the civil service but the interviews also highlight the problem of selective justice due to political interference and the ability of corrupt government officials to remain undetected. For example, a mid-level manager in the Ministry of Trade stated:

Yes, it has had a deterrent effect, there have been a lot of arrests. When you hear about cases and you see them being sent to prison, you see the difference: ‘Gentlemen, let's not get rich through crooked means, don't get rich by stealing.’ We discuss such things. It makes people think twice, it really makes you think.

The remaining 19 interviewees stated that the law enforcement effort had no or only a limited deterrent effect whilst also highlighting that the arrests and punishment of corrupt government officials and businesspeople did have an effect on government officials who became ‘very cautious’. However, six of the 19 government officials who had a more pessimistic outlook denied any deterrent effect and claimed that corrupt officials merely have become more adept at avoiding detection. According to one of them, a mid-level official in the Office of the President and Cabinet, ‘people have become more shrewd’ rather than deterred due to the law enforcement effort.

The interviews revealed significant changes in perception since 2012. The interviewees in the qualitative study stated that in 2013 the perpetrators were quite confident that they would not face punishment. They were assured protection by the key conspirators and were tempted by greed to benefit from the illegal transactions. As one interviewee put it succinctly: ‘Maybe they were deceived. They thought their bosses would protect them. It was pure self-interest, greed, to get the posh lifestyle.’ However, the impunity they were hoping for did not materialise due to the efforts pushing for prosecutions under both Joyce Banda and Arthur Peter Mutharika. It seems government officials who became involved in the illegal activities benefitted and acquired large amounts of cash, which they typically spent on vehicles and real estate. According to 23 officials interviewed in the qualitative study, political influence greatly affected the fraudulent transactions until September 2013, with certain officials being fast-tracked and promoted to strategic positions. According to a senior official in the Ministry of Education, ‘it was like a virus which was bound to spread across many Ministries’. All interviewees pointed out that the enrichment was conspicuous and unchecked, resulting in a feverish atmosphere around the government offices on Capital Hill in Lilongwe with lavish consumption, new cars and unexplained wealth openly displayed. According to our interviewees, the perpetrators felt very confident indeed. They were ‘very generous’ and explained their wealth was acquired by doing ‘business’, a common source of income for government officials (Anders Reference Anders2010: 70–98). They expected to enjoy impunity and wealth from what one interviewee dubbed ‘the Fountain’.

One of the interviewees, a senior lawyer in the Ministry of Justice, drew a comparison with the situation in 2010/11 when large-scale procurement fraud estimated at roughly 400 million Kwacha was discovered in several government agencies including the Malawi Police Service and the Accountant General's Office. However, the discovery by the Financial Intelligence Unit did not lead to any significant investigations and prosecutions at the time. He pointed out that participants in this scheme felt encouraged by the lack of sanctions and had a sense of impunity that directly fuelled the large-scale theft using the Integrated Finance Management Information System (IFMIS) in 2013. It is noteworthy that some of the key actors had also been implicated in the procurement fraud discovered in 2011.Footnote 13 This is backed up by several interviewees in the qualitative study who highlighted the low certainty of punishment in 2011 as a major contributing factor to the palpable sense of impunity in the government quarter on Capital Hill in 2013.

The mixed-methods evidence surrounding perceptions of deterrence among the government officials enrolled in our study in Malawi complements the findings of the qualitative study. As discussed previously, the conjoint experiment presented participants with hypothetical law enforcement scenarios and asked them to evaluate the potential for corruption deterrence in these scenarios. By randomly assigning the characteristics of the law enforcement scenarios, we were able to identify which characteristics make a perceived deterrent effect more or less likely. However, this approach is also quite abstract. To facilitate a more context-specific analysis of law enforcement and corruption deterrence, we compare the results from the conjoint experiment to the findings from the in-depth interviews.

Before we examine in detail the government officials’ perceptions with regard to certainty, swiftness and severity, we display the results of the conjoint experiment in Figure 1. In this figure, the horizontal lines represent the effect of each dimension on the outcome variable listed above the plot (point estimate with 90% confidence interval).Footnote 14 Lines below zero indicate lower corruption, and therefore a perceived deterrent effect, whereas lines above zero indicate higher corruption, and therefore the opposite of a perceived deterrent effect. Panel (A) shows how the various dimensions of the law enforcement environment affect perceived deterrence of corruption specifically among government officials, and Panel (B) shows how the various dimensions of the law enforcement environment affect perceived deterrence of corruption more generally (not only among government officials). In the discussion below, we will refer back to Figure 1 as we discuss certainty, swiftness and severity one by one.

Figure 1 Law enforcement causes of corruption deterrence in the conjoint experiment.

Certainty of punishment

The qualitative study highlighted the importance of certainty of punishment for government officials’ subjective deterrence. According to 61% of the officials we interviewed, the arrests and convictions of officials who expected to enjoy protection constituted an important step in increasing the perceived certainty of punishment. Similarly, in the conjoint experiment, the certainty of corruption detection increased perceived deterrence of corruption among government officials, as can be seen in line 1 of Figure 1, Panel (A), as well as of corruption more generally (i.e. not only among government officials), as can be seen in line 1 of Figure 1, Panel (B). The certainty of punishment also increased perceived deterrence of corruption among government officials (line 2, Figure 1, Panel A) as well as of corruption more generally (line 2, Figure 1, Panel B). Combining the findings of the interviews and the conjoint experiment, the results suggest that officials perceived certainty of punishment to be particularly important for corruption deterrence.

However, there is an important caveat to this encouraging finding. Among the interview participants, the sense that there is a much higher likelihood of punishment due to the law enforcement response is coupled with concerns about selective justice due to political influence. This view is exemplified in this statement by one of the interviewees, a mid-level official in the Ministry of Finance: ‘In a broad sense, the law enforcement response to Cashgate has a deterrent effect. Now people have to be more careful. At the same time, there is a perception that it is selective. That is the challenge for deterrence to be effective.’ This sentiment was echoed by a senior official in the Ministry of Finance who observed that ‘civil servants who are affiliated with the political authorities know that they will be protected as long as they keep placating the gods – sharing the benefits of fraud with their political masters.’

Resource constraints reinforce perceptions of selective justice. If funding and staff focus on specific cases the question arises whether there is a specific agenda behind resource allocation. The interviewees in the qualitative study highlighted how the logistical challenges faced by the law enforcement agencies can easily undermine the deterrent effect. Whilst the majority of the officials we interviewed perceived a deterrent effect of the law enforcement effort they were worried that it could easily be undone if corrupt officials, especially the ‘big fish’, would be allowed to escape justice. The politicisation of punishment was an important concern for the participants in the quantitative survey as well; 92% of respondents in the survey expressed concern about attempts to influence law enforcement from outside, shielding the ‘big fish’ with political connections. Further, in response to a question asking survey participants to evaluate various contributing factors to the highly conducive corruption environment in Malawi, the second most commonly cited identified issue was that the ‘anti-corruption response has not been adequate because it is biased in who is affected’.

The threat of selective justice is closely tied to Malawi's political system. Generally, representative democracy with regular alternation of power is seen to strengthen governance (Rose-Ackerman & Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). In Malawi specifically, the change of government following the 2014 election likely removed some political protection for government officials involved in Cashgate. Losing political protection, in turn, probably raised officials’ perception of punishment certainty, which further heightens the potential for deterrence.

Swiftness

Since Beccaria (Reference Beccaria1995 [1764]), speedy and proportionate punishment is considered to be key to deterrence and the rule of law. In Malawi, frequent delays and adjournments have been one of the main obstacles to the swift delivery of justice since the country's democratisation in 1994. Corruption cases are particularly prone to become drawn out affairs. For example, the main Cashgate trial against former Budget Director Paul Mphwiyo, former Accountant General David Kandoje and 16 other accused has been adjourned for long periods of time. Although the accused were formally charged at the High Court in Lilongwe in November 2015, pleas were not entered until November 2016, and the first witness was heard in January 2017. Frequent adjournments and a limited number of sitting days per month considerably slowed down the trial. These factors affecting swiftness are not limited to the Cashgate trials. Judges use broad discretion to adjourn trials, often interrupting them for weeks or even months. Further, the exercise of fair trial rights, including the right to secure legal representation, the right to appeal against any decision and ruling of the trial court, and the right to cross-examine all witnesses and alleged accomplices is time-consuming, especially in a system as poorly resourced as Malawi's (Kanyongolo Reference Kanyongolo2006).

In the eyes of the government officials we interviewed, the protection of fair trial rights is exploited by defence lawyers who aim to delay the legal proceedings. For example, one of the interviewees complained ‘that there are so many loopholes in the system. People are using the law to delay everything, there are too many injunctions’. Of course, it should be noted that this article does by no means suggest to limit fair trial rights of accused in corruption cases. It merely reports a common perception among government officials about the effectiveness of the judicial process.

According to the government officials we interviewed, the first wave of trials in 2014 and 2015 resulted in swift punishment of a number of people involved in Cashgate but they voiced concerns that since 2016 the trials had slowed down considerably. This development highlights the precarious nature of deterrence that can easily be undermined if the law enforcement effort is seen to be flagging. Similarly, in the conjoint experiment, swiftness in detection and punishment of corruption increased perceived corruption deterrence. Delays in either detecting or punishing corruption decreased perceived deterrence of corruption among government officials, as shown in lines 3 and 4 of Figure 1, Panel (A), and to hinder deterrence of corruption more generally, as shown in lines 3 and 4 of Figure 1, Panel (B). As with the conjoint experiment results regarding certainty, swiftness in detection appears to affect perceptions of deterrence more than does swiftness in punishment.

Severity of punishment

The interviewed officials were in favour of long prison sentences for maximum deterrent effect. It is important to note that several interviewees highlighted the need for long prison sentences regardless of the deterrent effects. They emphasised the important symbolic function of punishment for strengthening the rule of law in a context of weak institutions and only limited political support for law enforcement.

More specifically, the interviewees were positive about the long prison sentences handed down to some of the accused in Cashgate. In 2015, Maxwell Namata, a government accountant, was sentenced to eight years for money laundering and theft and Oswald Lutepo, a businessman and functionary in Joyce Banda's People's Party, received 11 years. By contrast, most of the interviewees criticised the punishment for Tressa Senzani, a former Principal Secretary in the Ministry of Wildlife and Tourism, as too lenient. She was sentenced to three years for money laundering and nine months for theft that were served concurrently. She was released early for good behaviour in October 2016 after serving a third of her sentence. Her early release was seen by participants in the study as evidence of selective justice benefiting those with political connections (Senzani's sister is a Member of Parliament and former Cabinet Minister). One of the interviewees voiced his concerns about what he saw as too lenient sentences:

People get the feeling they are getting away with it. One Principal Secretary [Senzani] was convicted and given three years. This is making a mockery of the whole system. If you steal a chicken you may face up to five years imprisonment but here is somebody who stole so many millions and is released after one and a half years! This sends out the wrong signal, we need punishment.

His view was widely shared by the government officials who were interviewed for the study. From their perspective, sentencing was inconsistent, for example ranging from three years for Senzani to 11 years for Lutepo for similar offences. Several officials specifically mentioned considerable discrepancies between the punishment for ‘normal’ offences such as ordinary theft versus punishment for Cashgate-related offences. It should be noted that Senzani received a reduced sentence because of her guilty plea but this was not seen as a factor by the government officials we interviewed. Striking the balance between rewarding defendants who plead guilty and provide important information, on the one hand, and punishment severe enough to have a deterrent effect, on the other, constitutes one of the principal challenges to effective law enforcement against corruption, as Rose-Ackerman & Palifka (Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016: 206) point out.

Surprisingly, the conjoint experiment indicates that the causal relationship between severity of punishment and deterrence is more of a mixed picture, in that more severe penalties for the corrupt actually decreased perceived corruption deterrence (line 5, Figure 1, Panel A and line 5, Figure 1, Panel B). This pattern holds across all sub-samples examined: junior vs. senior officials; and district-based vs. headquarters-based officials. We interpret this finding as indicative that harsh punishments may result in demoralisation and a sort of ‘panic’ within the civil service, rather than compelling government officials to refrain from corruption. This finding aligns with that of Kugler et al. (Reference Kugler, Verdier and Zenou2005) who use a formal theoretical model to demonstrate that harsher punishment in the context of weak government institutions can serve as a catalyst for criminal activity.

While we are unable to definitively reconcile the differing findings regarding punishment severity across the qualitative and quantitative evidence, we posit two possible explanations. One possible explanation pertains to the differing samples. The qualitative interviews only involved participants working on Capital Hill, where the headquarters of the principal line ministries are located, whereas the quantitative conjoint experiment involved participants outside of Capital Hill and at decentralised government offices in the districts. Perhaps those in the ministerial headquarters on Capital Hill perceived a closer link between punishment severity and corruption deterrence than those working elsewhere in government offices. A second possible explanation pertains to the differing questions about deterrence across the qualitative and quantitative research activities. In the qualitative interviews, participants were asked specifically about corruption deterrence after Cashgate, whereas in the quantitative conjoint experiment, Cashgate was never mentioned and the participants evaluated hypothetical law enforcement scenarios. Perhaps the abstract nature of the conjoint experiment made the link between punishment severity and corruption deterrence less salient than it was for those evaluating real examples drawn from the Cashgate context. As discussed below more extensively, probing the generalisability of our findings will be a promising avenue for future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Malawi has struggled to contain the spread of corruption since the introduction of multi-party democracy and economic liberalisation during the 1990s. Our findings highlight the extent of corruption in government departments in Malawi from the perspective of government officials. Levels of corruption in government departments remain high, with more than a quarter of officials who participated in the survey reporting involvement in corrupt practices.

Our findings indicate that Malawian government officials hold a realistic view of the shortcomings of the country's criminal justice system. However, government officials have keenly observed the law enforcement effort targeting the Cashgate scandal and our interviews suggest that it has had a deterrent effect on high-level corruption. Drawing on our mixed-methods evidence, we identify several factors as critical in maximising law enforcement's potential for corruption deterrence: the certainty of corruption detection and punishment; and swiftness in corruption detection and punishment; and punishment severity albeit less clearly and more ambiguous. With regard to the certainty of punishment, officials perceive that the law enforcement response to Cashgate has broken the pattern of almost complete impunity and the perceived likelihood of punishment has increased significantly. However, selective justice is viewed as a countervailing factor dampening any gains of more certain punishment. With regard to swiftness, our research reveals that swiftness in detection and punishment of corruption is a particularly strong deterrence driver.

We acknowledge that our research does not substitute for a full-fledged criminological deterrence study, which is currently not feasible in Malawi, but we nonetheless view these findings as indicative of the potential for deterrence in the Malawi context. We also note that our study was conducted with a specific sample at a particular point in time, and one avenue for future research would be to replicate our study over time, both in Malawi and elsewhere, to see how variations in law enforcement efforts influence perceptions of deterrence.

The case of Malawi speaks to broader debates about anti-corruption strategies and criminal justice in developing countries. It shows that even under-resourced and inconsistent law enforcement can have an impact on corruption. While concerned about the spread of corruption, government officials in Malawi in our study were positive about the potential for corruption deterrence by law enforcement even though they were keenly aware of the system's shortcomings. They also emphasised the symbolic importance of the law enforcement response to corruption in an environment where corrupt officials are generally neither shamed nor shunned by their communities and peers. We would anticipate that our findings would generalise to similar contexts, implying that even weak anti-corruption law enforcement is worth supporting, especially where corruption is culturally acceptable.

From a policy perspective, our findings highlight the importance of law enforcement efforts within a comprehensive anti-corruption strategy, in both addressing specific instances of corruption and challenging the perception that corrupt officials enjoy impunity. Without the perception of a credible threat of certain, swift and proportionate punishment, there is little hope that entrenched corruption can be curbed.