Abstract

Lithium treatment, initially considered specific for bipolar disorder, has since been shown to provide additional benefits in affective and other disorders. This variety of benefits should be taken into account when interpreting recently reported lower efficacy during lithium prophylaxis, as well as early relapses and loss of efficacy after lithium discontinuation. There are particularly striking parallels between these recent reports and earlier observations of “antipsychotic” lithium effects. Other factors, such as the accumulation of atypical, treatment-resistant patients in academic centers and, in particular, the broadening of diagnoses of affective disorders, further complicate the interpretation of the recent reports. Lithium, however, continues working well for patients with typical bipolar disorders, for whom it was originally proved effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It has been nearly 50 years since John Cade (1949) first reported on the specific treatment of acute mania with lithium salts and about 25 years since lithium was widely accepted as an effective long-term treatment. When lithium treatment first achieved wide acceptance, it was welcomed as a treatment that had the best demonstrated efficacy among psychiatric treatments. A series of double-blind as well as large open studies (as reviewed, for example, in Schou and Thomsen 1975; Schou 1982) demonstrated uniformly lithium's usefulness, as well as its superiority over a placebo and antidepressants in the long-term treatment of affective disorders. The double-blind discontinuation study of Baastrup et al. (1970) presented particularly robust findings, unparalleled in psychiatry, which showed that when bipolar and unipolar patients stabilized on lithium were randomly allocated to lithium and placebo, only the placebo patients subsequently relapsed.

In addition to its demonstrated efficacy, lithium was also thought to be a specific drug for manic-depressive illness. Cade was so struck by the specificity that he entertained the possibility of lithium deficiency in his patients. Later, the conviction about specificity was drawn mainly from the initial observations that lithium could prevent recurrences of primary affective disorders but not of other psychiatric conditions, and at the same time, had only negligible effects on normal moods. Lithium seemed to be a substance with a specific benefit, when compared with the broad spectrum of applications of other psychotropic agents. For example, tricyclic antidepressants could treat conditions as varied as mental depression, chronic pain, and nocturnal enuresis. This tenet of lithium's specificity was so mighty that clinicians often tended to conclude ex iuvantibus; when patients treated with lithium benefited, it was resolved that they must be suffering from some form of bipolar illness. In hindsight, it would have been more productive to question lithium's absolute specificity.

Over the years, however, the initially narrow scope of lithium's caliber in affective disorders has quickly expanded, adding to its well-established antimanic and prophylactic benefits antiaggressive effects (particularly studies of Sheard 1978, 1984), antipsychotic potential (e.g., investigations of Garver et al. 1988; Garver Hutchinson 1988; Lenz et al. 1987, Lenz et al. 1989), antisuicidal and mortality-reducing ability (specifically, studies of Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 1992; Coppen et al. 1992), and possibly also antidepressant Mendels 1976, 1982) and antidepressant-augmenting effects (de Montigny et al. 1983).

Surprisingly, while quickly expanding therapeutic horizons, lithium has also been reported to be gradually less and less effective (Grof et al. 1993; Guscott and Taylor 1994), particularly in clinical practice. Recent literature certainly paints a rather pessimistic picture; it seems now that only a fraction of patients actually benefit from lithium prophylaxis (Prien and Gelenberg 1989), and a sizeable proportion of patients may lose the benefit altogether over time (Post et al. 1992). Furthermore, discontinuation of lithium is often followed by a prompt recurrence of the illness (Suppes et al. 1991), and later possibly by a loss of efficacy (Post et al. 1992). In brief, recent literature suggests that although lithium treatment does not help much anymore, after its discontinuation, many patients may now suffer even more.

Thus, during the past two decades, the earlier perception of lithium as an effective and specific treatment has been changing from that of a highly valued, long-term treatment to a questionably useful substance of fleeting benefit. It is important to explore the nature of this shift and the possible misunderstandings that surround it. We suggest that a combination of several factors has contributed to this controversy, in particular a lack of recognition that lithium treatment offers more than one distinct clinical benefit; a broadening of the diagnoses of affective disorders; the need to differentiate between efficacy and effectiveness; and an accumulation of difficult-to-treat affective disorders in academic research centers.

VARIETY OF LITHIUM EFFECTS

A variety of distinct effects of lithium treatment have been described, along with their clinical characteristics.

“Prophylactic,” Normal Mood Stabilizing Effect

The important clinical characteristics of this most widely utilized, well-documented benefit have been outlined, in particular, in the large series of the studies of lithium in the late 1960s and early 1970s. First, the recurrences of abnormal moods were significantly reduced in about three-quarters of the patients, either suppressed completely or reduced substantially in frequency. Second, both expected manias and expected depressions were significantly reduced. Third, the prophylactic effect was dependent upon therapeutic lithium concentrations, and toxicity was observed only with elevated lithium levels. Fourth, when lithium treatment was discontinued in remission, subsequent recurrences developed gradually, and no rebound was observed. The benefit was generally reproducible by reinstituting lithium treatment.

Antimanic Effect

The value of lithium as an antimanic drug has been well established against a placebo and neuroleptics; therefore, lithium is now considered the standard antimanic drug. Similar to the current controversy about lithium's prophylactic efficacy, recent findings about the antimanic effects of lithium have been less uniform, some confirming (Bowden et al. 1994) and others questioning lithium's superiority over placebo. The issue of whether the prophylactic and antimanic benefits are of the same nature and exert themselves in the same patients has not yet been systematically investigated. Clinically, there seems to be an association. However, the antimanic effect at times seems to act with a wider range, as if there were at least two possible mechanisms involved: a relatively specific effect in bipolar mania; and a nonspecific, overactivity-reducing effect in some pathological states of other provenience. Further understanding of lithium's antimanic activity may surface from the emerging comparative studies with such antiepileptics as valproic acid and lamotrigine.

Antiaggressive Effect

The antiaggressive effects of lithium have been demonstrated amply in a series of studies, in particular, Sheard (1978, 1984). The effects were documented in several different populations: psychiatric patients, mentally retarded populations, and penitentiary subjects. Sheard and other investigators who studied the antiaggressive effects of lithium argued convincingly that subjects who benefited did not suffer from bipolar illness: the effect was distinctly different.

“Antipsychotic” Effect

In terms of lithium's specificity, probably one of the most perplexing effects of lithium has been its “antipsychotic” capacity. Both acute and long-term “antipsychotic” effects have been described best by Garver and his group (Garver et al. 1984, 1988) in schizophrenias and schizophreniform psychoses, and illustrated on schizoaffective psychoses by many others (e.g., Angst et al. 1970; Lenz et al. 1987; Lenz et al. 1989) and can commonly be seen clinically. During treatment with lithium alone, a dramatic clearing of psychotic symptoms has been seen in acute psychoses (schizoaffective and schizophreniform), even in mood incongruent ones, and in many patients, continued treatment with lithium alone could prevent further episodes. Garver et al., for example, treated a large consecutive series of mood incongruent psychotic episodes with lithium only. These patients were diagnosed as having DSM-III affective, mood-incongruent psychoses, schizoaffective disorders, schizophreniform disorders, and schizophrenias. None had received depot neuroleptics within 6 weeks of admission. Each patient underwent a systematic trial with lithium carbonate alone, with plasma levels in the range of 1.0 to 1.2 mEq. Excellent responses with remission were seen in 29% of patients. Lithium responders fared well, without the introduction of neuroleptics at any time during the course of hospitalization and could be discharged on lithium alone, essentially symptom free. Of the lithium-responsive patients who were readmitted, about half showed a concordant lithium response on readmission. Unlike the generally reproducible response to lithium in typical affective disorders, in only half of these atypical patients could the response be replicated. Using the terminology of recent years, we could say that the initially well-proved response “was lost” in one-half of the patients.

This “antipsychotic” effect of lithium superficially resembles both the prophylactic and antimanic effects, although closer observation exposes a different profile. First, patients benefiting from the antipsychotic effect of lithium experience a reduction of manias but no reduction in their depressive episodes (Grof 1994). Second, when these patients are readmitted for mania, the antimanic effect is reproducible in only about half of the patients (Garver et al. 1988; Garver and Hutchinson 1988), as if there had been a loss of efficacy over time or a loss of efficacy on discontinuation. It would seem that, for a satisfactory long-term effect, in about half of these initial responders, lithium treatment must eventually be combined with, or replaced by, other psychotropic drugs. Third, lithium toxicity may develop, even with therapeutic lithium levels. Fourth, when lithium is discontinued, patients with atypical affective or mood-incongruent disorders frequently present with early relapses (Lenz et al. 1988, Grof 1994).

These observations strongly suggest that the prophylactic, normal mood-stabilizing effect in typical affective disorders and the “antipsychotic” effect in atypical disorders are two different benefits, with possibly connected, but different, underlying mechanisms. It may be prudent to consider these two lithium benefits separately, both at the clinical and the basic science level.

Reduction of Suicidal Behavior and Mortality

There now exists a large body of data compatible with the conclusions that long-term lithium treatment markedly reduces mortality and suicidal behavior and that the mortality of affective disorders is diminished to a level indistinguishable from that of the general population (e.g., Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 1992, Coppen et al. 1992). The antisuicidal effect is also supported by findings from a comparative, long-term study of lithium and carbamazepine, in which only lithium-treated patients remained completely free of suicides (Greil et al. 1997). In patients with a history of suicide attempts, a reduction was observed both in responders and nonresponders to lithium treatment, indicating that this distinct antisuicidal benefit takes place over and above lithium's prophylactic effect.

Antidepressive Effect and Lithium Augmentation

The antidepressive effect of lithium was first reported by Vojtechovsky and later documented (in particular, (Mendels 1976, 1982). This effect can be prompt and quite marked in depressed patients who suffer from some form of bipolar illness, but it has not yet been studied systematically enough. There seems to be clinical agreement that the antidepressive effect of lithium is infrequent, which is in contrast with the commonly observed antimanic effect.

Since 1981, de Montigny et al. (e.g. 1983) have developed the concept of augmenting antidepressants by adding lithium. The idea of such a combination has been supported by other observations in the literature and found clinically useful, although the evidence for a “rapid augmentation” (acting within 48 hours) seems less clear. One of the interesting features of augmentation is that it may work even in the absence of therapeutic lithium levels. Thus, this clinically useful phenomenon may require additional investigations of the underlying mechanisms.

Implications

Lithium may possibly still be considered more specific than other psychotropic drugs; however, it clearly exhibits more than one clinically distinct, qualitatively different effect. To wit, prophylactic effect (stabilizing normal mood) and “antipsychotic” effect are each linked with different clinical characteristics. Some of the effects may have a common denominator in improved serotonergic function, but the clinical effects have distinguishing features and may reflect different mechanisms of action and differences in the pathophysiology of treated conditions. It would be prudent to study these phenomena separately for each effect, in particular for the prophylactic and “antipsychotic” effects, and separately in patients with typical affective disorders for whom the efficacy of lithium was originally proved. Averaging from heterogeneous groups can only blur any findings.

So far, we have focused on the variety of benefits lithium administration can offer. The other factors that confound the evaluation of lithium's prophylactic value are mentioned only briefly, because they have already been described elsewhere: the need to differentiate between efficacy and effectiveness; accumulation of treatment-resistant patients in academic centers; and broadening of the diagnosis of affective disorders.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN EFFICACY AND EFFECTIVENESS

When interpreting the reports on the low success of lithium therapy, it is very important to keep in mind the difference between evaluating efficacy and effectiveness, as Guscott and Taylor (1994) tellingly related. When evaluating efficacy in the initial clinical trials, patients are selected according to strict criteria. The procedure should optimize detection of the putative efficacy of the evaluated new substance. This is neither the case in clinical practice, nor in clinical trials during the later stages.

ACCUMULATING TREATMENT-RESISTANT PATIENTS

Academic centers, which have become the main performer of clinical trials, tend to accumulate more than their share of difficult, atypical, treatment-resistant patients with affective disorders who then enter clinical trials (e.g., Gershon 1996 and other investigators).

BROADENING THE DIAGNOSIS OF AFFECTIVE DISORDER

There is now substantial evidence that during the past two decades, affective disorders have been diagnosed more liberally. In the 1950s, during the days of enthusiastic psychotherapy of schizophrenia, there was concern about the “disappearing manic depressive.” Conversely, during the fervent use of lithium and antidepressants, investigators (e.g., Baldessarini 1970; Grof and Fox 1987; Stoll et al. 1993) documented a strong opposite trend favoring the diagnoses of affective disorders, at the expense of other psychiatric conditions.

Because of different circumstances, 25 years ago, patients were placed on long-term lithium according to narrower diagnostic criteria and after a much longer period of diagnostic observation. For example, before lithium treatment, Baastrup and Schou's (1967) patients experienced nine episodes of illness on the average. At present, many patients with only two episodes of mood disorder will be considered appropriate for lithium prophylaxis. Making an accurate diagnosis and estimating recurrence risk becomes much more challenging. Thus, as a result of the shorter observation period combined with an expanded diagnostic approach, many patients who would not have been placed on lithium 25 years ago are now entering clinical investigations. An especially confusing element of this tendency has been the addition of the mood-incongruent psychoses to affective disorders in DSM-III.

As we have shown recently (Grof et al. 1995), compared to 25 years ago, the patients included in many recent studies of affective disorder differ not only in lower treatment responsiveness, but in many other characteristics as well: pre-existing psychopathology; age at onset; clinical course; comorbidity; and so forth. For example, in family studies, the proportion of relatives diagnosed with affective disorders has increased five to six times over the past 20 years, and a review indicates that this increase may have taken place at the expense of other diagnostic categories. Clearly, the recent studies deal with different populations of affective disorders, diagnosed more broadly than 25 years ago, including those in whom prophylactic lithium effects were not demonstrated.

DISCUSSION

Since the original studies of lithium in the late 1960s and early 1970s, several noteworthy changes have occurred. In the wider use of lithium, a variety of other benefits has been described. Opinions may vary about the actual specificity of lithium, but such effects as prophylactic, antiaggressive, and antipsychotic exhibit distinct clinical features. Furthermore, for several reasons, the populations researched and treated with lithium today differ from those for whom lithium was proved effective. As a result, the earlier perception of lithium as an effective and specific treatment has been markedly changing. If correct, this mutation would be a sad state of affairs — rather tragic for clinical practice, confusing for research, and certainly, a source of medicolegal problems, because lawyers now bring suits for either prescribing lithium, or discontinuing it or not prescribing it.

Parenthetically, clinical and medicolegal concerns about tardive dyskinesia have often led to overemphasizing mood abnormalities and treating patients with lithium in place of, or in combination with, a low dose neuroleptic. In some jurisdictions, a psychiatrist now must provide special justification for prescribing a neuroleptic but not for such other psychotropic drugs as lithium. As recent statistics indicate, lithium has been given, alone and in combination, to a majority of inpatients in several U.S. hospitals (Baldessarini et al. 1995). Such statistics make sense only if lithium is given widely outside of its proved indications.

While we are exploring what seem to be new phenomena in lithium prophylaxis — markedly reduced long-term efficacy, and after discontinuation, both early relapses and a frequent loss of efficacy — it may be useful to keep in mind that several important ingredients have changed since the initial studies, and phenomena similar to the newly reported ones have already been observed in connection with the antipsychotic effect of lithium. These new phenomena are real, but the question remains whether they are expandable to those patients for whom lithium was demonstrated as effective prophylactic treatment more than two decades ago.

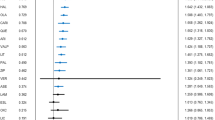

There are parallels between the new observations and some of the features of the earlier described “antipsychotic” effects of lithium. Naturally, a parallel is not a proof; however, these analogies between the recent findings about lithium prophylaxis and the earlier reports in atypical and schizophreniform disorders are rather striking; in both cases only less than 30% of patients benefited from prophylaxis (22% Prien and Gelenberg 1989 vs. 27–29% Garver et al. 1988); in both cases, there is no beneficial effect on depression (Prien and Gelenberg 1989; Grof 1994) after lithium discontinuation, a rebound and early relapses have been reported often in both (e.g., Lenz et al. 1988, 1989; Suppes et al. 1991; Grof 1994), and, finally, in both groups, after lithium discontinuation, reintroducing lithium has been helpful only in about half the cases (46% Post et al. 1992 vs. 50% Garver et al. 1988).

Lithium continues working well for patients for whom it was proved effective (Berghöfer et al. 1996; Greil et al. 1994). In a recently completed study, when patients were carefully divided into typical (unipolar and bipolar) and atypical (schizoaffective), lithium was clearly prophylactically superior to carbamazepine in bipolar patients and to amitriptyline in unipolar ones, while being poorly effective, less so than carbamazepine, in schizoaffective disorders (Greil et al. 1994). Furthermore, in typical affective disorders treated in specialized clinics, there was no evidence of a loss of efficacy after discontinuation (e.g., Berghöfer et al. 1996) and no evidence for rebound (Grof 1994). We must assume, however, that if typical and atypical patients were mixed in one study, the result would depend primarily on the proportion of each group. Thus, the trends mentioned above pose a considerable challenge for the interpretation of research findings and for the development of useful guidelines for clinical practice.

References

Angst J, Weis P, Grof P, Baastrup PC, Schou M . (1970): Lithium prophylaxis in recurrent affective disorders. Brit J Psychiat 116: 604–614

Baastrup PC, Schou M . (1967): Lithium as a prophylactic agent. Its effect against recurrent depressions and manicdepressive psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiat 16: 162–172

Baastrup PC, Poulsen JC, Schou M, Thomsen K, Amdisen A . (1970): Prophylactic lithium: Double-blind discontinuation in manic-depressive and recurrent-depressive disorders. Lancet 2: 326–330

Baldessarini RJ . (1970): Frequency of diagnosis of schizophrenia versus affective disorders from 1944 to 1968. Am J Psychiat 127: 759–763

Baldessarini RJ, Kando JC, Centorrino F . (1995): Hospital use of antipsychotic agents in 1989 and 1993. Am J Psychiat 152: 1038–1044

Berghöfer A, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Ahrens B . (1996): Loss of efficacy after discontinuation? Paper presented at the International Lithium Conference, Malta, November 1995.

Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, Garza-Trevino ES, Risch SC, Goodnick PJ, Morris DD . (1994): Efficacy of divalproex vs. lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 271: 918–922

Cade J . (1949): Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitment. Med J Australia 2: 349–352

Coppen A, Bailey J, Houston B, Silcocks P . (1992): Lithium and mortality: A 15-year follow-up. Clin Neuropharmacol 15: 448A–449A

de Montigny C, Cournoyer G, Morisette R, Langlois R, Cailler G . (1983): Lithium carbonate addition in tricyclic antidepressant-resistant unipolar depression: Correlations with the neurobiologic actions of tricyclic antidepressant drugs in lithium ion on the serotonin system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 40: 1327–1333

Garver DL, Hirschowitz J, Fleishmann R, Djuric PE . (1984): Lithium response and psychoses: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychiatry Res 12: 57–68

Garver DL, Hutchinson LJ . (1988): Psychosis, lithiuminduced antipsychotic response, and seasonality. Psychiatry Res 26: 279–286

Garver DL, Kelly K, Fried KA, Magnusson M, Hirschowitz J . (1988): Drug response patterns as a basis of nosology for the mood-incongruent psychoses (the schizophrenias). Psycholog Med 18: 873–885

Gershon S . (1996): Comments at the John Cade Symposium, 20th CINP, Melbourne, Australia.

Greil W, Ludwig-Mayerhofer W, Erazo N, Schochlin C, Schmidt S, Engel RR, Czernik A, Giedke H, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Osterheider M, Rudolf GA, Sauer H, Tegeler J, Wetterling T . (1997): Lithium versus carbamazepine in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders—a randomized study. J Affect Disord 43: 151–161

Grof P, Fox D . (1987): Admission rates and lithium therapy. Brit J Psychiat 150: 264–265

Grof P, Alda M, Grof E, Fox D, Cameron P . (1993): The challenge of predicting response to stabilizing lithium treatment: The importance of patient selection. Brit J Psychiat 163: 16–19

Grof P . (1994): Lithium discontinuation in typical and atypical affective disorders. Abstracts, 19th CINP, Washington, June 1994.

Grof P, Alda M, Ahrens B . (1995): Clinical course of affective disorders. Were Emil Kraepelin and Jules Angst wrong? Psychopathology 28: 73–80

Guscott R, Taylor L . (1994): Lithium prophylaxis in recurrent affective illness. Efficacy, effectiveness, and efficiency. Br J Psychiat 164: 741–746

Lenz G, Lovrek A, Thau K, Topitz A, Denk A, Simhandl C, Wancata J, Wolf R . (1987): Lithiumprophylaxis of schizoaffective disorders (in German). Wien Med Wochenschr 137: 5

Lenz G, Lovrek A, Thau K, Topitz A, Denk A, Simhandl C, Wancata J, Wolf R . (1988): Lithium withdrawal study in schizoaffective patients. In Birch N J (ed), Lithium; Inorganic Pharmacology, and Psychiatric Use. Oxford, IRL Press Ltd

Lenz G, Wolf R, Simhandl C, Topicz A, Berner P . (1989): Long-term progosis and recurrence prophylaxis of schizoaffective psychoses (in German). In Marneros, A (ed), Schizoaffektive Psychosen (Tropon Symposium, vol IV). Berlin, Springer, pp 55–66

Mendels J . (1976): Lithium in the treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatr 133: 373–378

Mendels J . (1982): Role of lithium as an antidepressant. Mod Prob Pharmacopsychiat 18: 138–144

Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Ahrens B, Grof E, Grof P, Alda M, Schou M, Thau K, Wolf R, Lenz G . (1992): The effect of long-term lithium treatment on the mortality of patients with manic-depressive illness and schizoaffective illness. Acta Psychiat Scand 86: 218–222

Post RM, Leverich GS, Altschuler L, Mikalauskas K . (1992): Lithium discontinuation-induced refractoriness: Preliminary observations. Am J Psychiat 149: 1727–1729

Prien R, Gelenberg AJ . (1989): Alternatives to lithium for the preventative treatment of bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiat 146: 840–848

Schou M, Thomsen K . (1975): Lithium prophylaxis of recurrent endogenous affective disorders. In Johnson FR (ed), Lithium Research and Therapy. New York, Academic Press, pp 3–85

Schou M . (1982): Trends in lithium treatment and research during the last decade. Pharmacopsychiatria. 15: 128–130

Sheard MH . (1978): The effect of lithium and other ions on aggressive behavior. Mod Prob Pharmacopsychiatry 13: 53–68

Sheard MH . (1984): Clinical pharmacology of aggressive behavior. Clin Neuropharmacol 7: 173–183

Stoll AL, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ, Goodwin DC, Stein S, Katz S, Greenens D, Swinson RP, Goethe JW, McGlahan T . (1993): Shift in diagnostic frequencies of schizophrenia and major affective disorders at six North American psychiatric hospitals 1972–1988. Am J Psychiat 150: 1668–1673

Suppes T, Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Tohen M . (1991): Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat 48: 1082–1088

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grof, P. Has the Effectiveness of Lithium Changed? Impact of the Variety of Lithium's Effects. Neuropsychopharmacol 19, 183–188 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00023-2

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00023-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Virtual controls as an alternative to randomized controlled trials for assessing efficacy of interventions

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2021)

-

Stability of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder - long-term follow-up of 346 patients

International Journal of Bipolar Disorders (2013)

-

Increased extracellular serotonin level in rat hippocampus induced by chronic citalopram is augmented by subchronic lithium: neurochemical and behavioural studies in the rat

Psychopharmacology (2003)