Abstract

The simultaneous intravenous (i.v.) administration of heroin and cocaine, called a “speedball,” is often reported clinically, and identification of effective pharmacotherapies is a continuing challenge. We hypothesized that treatment with combinations of a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, indatraline, and a mu partial agonist, buprenorphine, might reduce speedball self-administration by rhesus monkeys more effectively than either drug alone. Speedballs (0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin) and food (1 g banana pellets) were available in four daily sessions on a second-order schedule of reinforcement [fixed ratio (FR)4; variable ratio (VR)16:S]. Monkeys were treated for 10 days with saline or ascending dose combinations of indatraline (0.001-0.032 mg/kg/day) and buprenorphine (0.00032–0.01 mg/kg/day). Two combinations of indatraline (0.32 and 0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.10 and 0.18 mg/kg/day) significantly reduced speedball self-administration in comparison to the saline treatment baseline (p < .01– .001), whereas the same doses of each compound alone had no significant effect on speedball-maintained responding. Daily treatment with 0.56 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine produced a significant downward shift in the speedball dose-effect curve (p < .01) and transient changes in food-maintained responding. These findings suggest that medication mixtures designed to target both the stimulant and opioid component of the speedball combination may be an effective approach to polydrug abuse treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Cocaine and heroin abuse continue to be major drug abuse problems in the United States (NIDA 1999). Treatment admission reports, emergency ward mentions, and mortality data indicate that among primary heroin abusers, cocaine is usually the most common secondary drug of abuse (NIDA 1999). The simultaneous intravenous administration of cocaine and heroin, often called a “speedball,” is one common form of polydrug abuse (NIDA 1999; Schütz et al. 1994). Crack cocaine is sometimes dissolved with vinegar or lemon juice to permit intravenous injection alone, or in combination with heroin (NIDA 1999). It is obvious that multiple drug use presents a formidable challenge for medication-based treatment approaches. The currently approved pharmacotherapies for opioid abuse have been only moderately effective in reducing polydrug abuse, and continued opioid and cocaine abuse by methadone-maintained patients is often reported (Condelli et al. 1991; Kosten et al. 1989b; Schottenfeld et al. 1993, 1997). Treatment of concurrent cocaine and heroin abuse is further complicated by the fact that there is no effective pharmacotherapy for cocaine abuse alone (Mendelson and Mello 1996).

The ways in which cocaine and heroin interact to maintain speedball abuse are poorly understood, but most clinical studies suggest that opioids enhance the subjective effects of cocaine. For example, methadone-maintained subjects (50 mg/day, p.o.) had greater positive subjective responses (liking, good effect, rush) and cardiovascular responses to acute i.v. doses of cocaine (12.5–50 mg, i.v.) than opioid abusers who were not maintained on methadone (Preston et al. 1996). Similarly, subjects maintained on high methadone doses (70–80 and 90–100 mg/day, p.o.) reported significantly greater subjective responses (stimulated, liking, quality, good drug) to acute doses of i.v. cocaine (8 or 16 mg/70 kg) than subjects maintained on lower methadone doses (20–60 mg/day, p.o.) (Foltin et al. 1995).

In clinical studies of speedballs, the subjective effects of cocaine and opioid (morphine or hydromorphone) combinations were usually greater than the subjective effects of either drug alone (Foltin and Fischman 1992; Walsh et al. 1996). The maximum response for subjective effect measures was similar after cocaine alone and cocaine and opioid combinations, and occurred within 1 to 2 min (Walsh et al. 1996). Although positive mood scores were higher after speedball administration than after either component drug alone, these effects were less than additive (Foltin and Fischman 1992; Walsh et al. 1996). In human polydrug abusers, speedball combinations usually produced a compound stimulus that included aspects of both component drugs (Foltin and Fischman 1992).

Preclinical studies also suggest that opioids may increase the abuse-related effects of cocaine. For example, opioids usually increase the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys (Rowlett and Spealman 1998; Spealman and Bergman 1992, 1994) and in rhesus monkeys (Mello et al. 1995; Negus et al. 1998a). Cocaine and heroin combinations produce robust reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects in rats and rhesus monkeys (Hemby et al. 1996, 1999; Mello and Negus 1998; Mello et al. 1995; Negus et al. 1998a; Rowlett et al. 1998; Rowlett and Woolverton 1997). Moreover, cocaine and heroin may enhance each other's reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects when administered in a speedball (Negus et al. 1998a; Rowlett and Woolverton 1997). Neurochemical findings suggest that self-administration of cocaine and heroin in combination has synergistic effects on extracellular dopamine release at the nucleus accumbens in rats (Hemby et al. 1999). Dopamine levels measured by microdialysis remained at baseline levels during heroin self-administration, increased by 400% during cocaine self-administration and increased by 1000% during speedball self-administration (Hemby et al. 1999). Cocaine dialysate levels were equivalent during cocaine alone and speedball self-administration, and therefore could not account for the increases in dopamine release during speedball self-administration (Hemby et al. 1999).

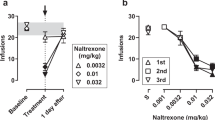

Treatment with opioid antagonists or dopamine antagonists alone has not been effective in reducing speedball self-administration in preclinical studies. The long-acting opioid antagonist naltrexone (3.2–1600 μg/kg, i.m.) dose-dependently decreased self-administration of heroin alone (6.4 or 13 μg/kg/inj) and some speedball combinations, but these effects were surmounted by increasing the dose of heroin (Rowlett et al. 1998). Acute treatment with naltrexone had no effect on cocaine (100 μg/kg/inj) self-administration (Rowlett et al. 1998), and this finding was consistent with earlier studies of the effects of naltrexone on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys (Mello et al. 1990, 1993b) and in rats (Corrigall and Coen 1991). The effects of naltrexone alone, and the dopamine D2 antagonist eticlopride alone, on speedball self-administration were compared in rats (Hemby et al. 1996). Naltrexone (3.0–30 mg/kg) antagonized the rate-suppressant effects of the speedball combination, but the resulting speedball dose-effect curve was not significantly different from that for cocaine alone (Hemby et al. 1996). Acute administration of eticlopride (0.03–0.3 mg/kg) produced a downward shift in the speedball dose-effect curve that was more pronounced at high (18 μg) than low (5.4 μg) doses of heroin in combination with cocaine (Hemby et al. 1996). The authors concluded that antagonism of both dopamine and opioid receptors may be necessary to significantly reduce speedball self-administration (Hemby et al. 1996).

A combination of the dopamine antagonist flupenthixol and the opioid antagonist quadazocine was more effective in reducing the discriminative stimulus effects of speedballs by rhesus monkeys than either antagonist alone (Negus et al. 1998a). These findings led us to examine the effects of the same flupenthixol and quadazocine combination on speedball self-administration by rhesus monkeys (Mello and Negus 1999). We found that 10 days of treatment with a combination of flupenthixol and quadazocine reduced speedball self-administration significantly in comparison to saline treatment, whereas the same doses of each antagonist alone had no significant effect on speedball-maintained responding. These findings are consistent with the notion that medication combinations may be a useful approach to polydrug abuse treatment. However, the effects of this dopamine antagonist + opioid antagonist combination on speedball self-administration were not sustained over 10 days of treatment (Mello and Negus 1999). Dopamine antagonists usually have transient effects on cocaine self-administration, and these effects are not prolonged by increasing the antagonist dose (Kleven and Woolverton 1990; Negus et al. 1996; Richardson et al. 1994). One important limitation of antagonist medications for clinical treatment of drug abuse has been problems with patient retention (Mendelson and Mello 1996). Naltrexone has been relatively ineffective in outpatient treatment because it could be discontinued without precipitating withdrawal signs or symptoms, and it had no positive mood modulating effects (National Research Council Committee on Clinical Evaluation of Narcotic Antagonists 1978; Schecter 1980).

Agonist-substitution type pharmacotherapies such as methadone and buprenorphine have been more effective than naltrexone in maintaining opioid-dependent patients in treatment (Mello and Mendelson 1995; O'Brien 1996). Given the transient effects of the flupenthixol + quadazocine combination described above (Mello and Negus 1999), we postulated that the combination of a long-acting monoamine reuptake inhibitor indatraline, and a mu opioid partial agonist buprenorphine, might be more effective in producing sustained decreases in speedball self-administration. The potential ability of this drug combination to reduce speedball self-administration was suggested by our recent studies of the effects of indatraline on cocaine self-administration and discrimination (Negus et al. 1999) and our previous studies of the effects of buprenorphine on cocaine, heroin and speedball self-administration (Mello and Mendelson 1995; Mello and Negus 1998).

The purpose of the present study was to compare the effects of chronic treatment with indatraline and buprenorphine alone, and in combination, on speedball self-administration by rhesus monkeys. Indatraline was selected because it directly competes with cocaine for binding sites on the dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters and because it has a long duration of action (Rothman and Glowa 1995; Negus et al. 1999). Moreover, some monoamine reuptake inhibitors produce some cocaine-like behavioral effects and alter cocaine self-administration in a manner consistent with the conclusion that they may substitute for cocaine's reinforcing effects (Glowa et al. 1995a,b; Kleven and Koek 1998; Negus et al. 1999; see Rothman and Glowa 1995 for review). Indatraline (0.1–0.56 mg/kg/day) produced dose-dependent and sustained decreases in cocaine (0.0032–0.1 mg/kg/inj) self-administration by rhesus monkeys (Negus et al. 1999). Indatraline (0.1–1.0 mg/kg) also produced cocaine-appropriate responding in monkeys trained to discriminate cocaine from saline. Insofar as indatraline produced cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects, it may prove useful as a substitute agonist medication for cocaine abuse treatment (Negus et al. 1999; Rothman and Glowa 1995).

The long-acting mu opioid partial agonist buprenorphine was selected for study because it has been shown to reduce heroin abuse in inpatient and outpatient clinical studies (Johnson et al. 1992; Mello and Mendelson 1980), and to reduce cocaine abuse by persons dually dependent on cocaine and opioids (Gastfriend et al. 1993; Kosten et al. 1989a,b; Schottenfeld et al. 1993). In rhesus monkeys, chronic treatment with buprenorphine selectively reduced self-administration of cocaine alone (Mello et al. 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993a,b) and heroin alone (Mello et al. 1983; Mello and Negus 1998). However, in monkeys trained to self-administer speedballs, the effectiveness of buprenorphine varied as a function of the unit dose of cocaine in the speedball (Mello and Negus 1998). Buprenorphine (0.237 mg/kg/day) was most effective when heroin was combined with a low (0.001 mg/kg/inj) or a high (0.10 mg/kg/inj) unit dose of cocaine on the ascending or descending limb of the cocaine dose-effect curve. These findings are consistent with our earlier reports that buprenorphine (0.237–0.70 mg/kg/day) reduced self-administration of relatively high unit doses of cocaine (0.05 and 0.10 mg/kg/inj) by rhesus monkeys (Mello et al. 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993a,b). Buprenorphine was least effective when heroin was combined with an intermediate unit dose of cocaine (0.01 mg/kg/inj) that was at the peak of the dose-effect curve for cocaine alone (Mello and Negus 1998).

We now report that chronic treatment with an indatraline and buprenorphine combination reduced self-administration of a speedball combination of 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin more effectively than the same doses of either indatraline or buprenorphine alone. Moreover, a combination of indatraline and buprenorphine produced a significant downward shift in the speedball self-administration dose-effect curve. These findings extend our previous study of speedball treatment with a dopamine and opioid antagonist combination and further suggest that medication combinations may be a useful approach to the treatment of speedball abuse.

METHODS

Subjects

Five rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), one male (12241) and four females (075F, 89B211, 89B157, Ch701) were studied. Monkeys weighed between 6 and 12 kg and all had self-administered cocaine for at least one year before cocaine + heroin speedball combinations were made available. Speedball-maintained responding was studied for at least six months before these studies began. Monkeys received multiple vitamins, fresh fruit and vegetables and Lab Diet Jumbo Monkey Biscuits (PMI Feeds Inc., St. Louis, MO) to supplement a banana-flavored pellet diet, fortified with vitamin C (P.J. Noyes Co., Lancaster, NH). Food supplements were given between 5:00 and 5:30 p.m. Water was continuously available. A 12-hr light-dark cycle was in effect (lights on 7 a.m.-7 p.m.), and the experimental chamber was dark during food and drug self-administration sessions.

Animal maintenance and research were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (ILAR-NRC 1996). The facility is licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Monkeys were observed at least twice every day. Any changes in general activity were noted. The observer was not blind to the treatment condition. In addition, the health of the monkeys was periodically monitored by consultant veterinarians trained in primate medicine. Operant food and drug acquisition procedures provided an opportunity for enrichment and for monkeys to manipulate their environment (Line 1987). Monkeys had visual, auditory and olfactory contact with other monkeys throughout the study.

Surgical Procedures

Double lumen Silicone® rubber catheters (I.D. 0.028 in, O.D. 0.088 in) (Saint Gobain Performance Plastics, Beaverton, MI) were surgically implanted in the internal jugular or femoral vein and exited in the mid-scapular region. All surgical procedures were performed under aseptic conditions. Monkeys were initially sedated with ketamine (5–10 mg/kg, i.m.), and anesthesia was induced with sodium thiopental (10 mg/kg, i.v.). Atropine (0.05 mg/kg, s.c. or i.m.) was administered to reduce salivation. Following insertion of an endotracheal tube, anesthesia was maintained with isofluorane (1–2% mixed with oxygen). After surgery, monkeys were given procaine penicillin G at 20,000 units/kg, i.m. twice daily for five days, or cephalexin 20 mg/kg, p.o. twice daily for five days. An analgesic dose of buprenorphine (0.032 mg/kg, i.m.) was administered twice daily for three days.

The intravenous catheter was protected by a tether system consisting of a custom-fitted nylon vest connected to a flexible stainless-steel cable and fluid swivel (Lomir Biomedical, Inc., Malone, NY). This flexible tether system permits monkeys to move freely. Catheter patency was evaluated periodically by administration of either a short-acting barbiturate, methohexital sodium (3 mg/kg), or ketamine (5 mg/kg) through the catheter lumen. If muscle tone decreased within 10 sec after drug administration, the catheter was considered patent.

Behavioral Procedures and Apparatus

Monkeys were housed individually in stainless steel chambers (64 × 64 × 79 cm) equipped with a custom-designed operant response panel (28 × 28 cm), a pellet dispenser (Gerbrands Model G5210, Arlington, MA), and two syringe pumps (Model 981210, Harvard Apparatus, Inc., South Natick, MA), one for each lumen of the double-lumen catheter. During food self-administration sessions, the response key on the operant panel was illuminated with a red light, and responding under an FR4 (VR16:S) schedule resulted in presentation of a 1 g banana-flavored pellet (P.J. Noyes Co.). During drug self-administration sessions, the response key was illuminated with a green light, and responding under an FR4 (VR16:S) schedule resulted in delivery of 0.1 ml of saline or a drug solution over 1 sec through one lumen of the double-lumen catheter. A 10-sec time-out followed delivery of each drug or saline injection or food pellet. Schedules of reinforcement were implemented using custom-designed software and IBM-compatible computers and interface systems (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Additional details of this apparatus have been described previously (Mello et al. 1995).

Four food sessions and four drug sessions were conducted during each experimental day. Food sessions began at 6 a.m., 11 a.m., 3 p.m., and 7 p.m., and drug sessions began at 7 a.m., 12 noon, 4 p.m,. and 8 p.m. At all other times, responding had no scheduled consequences. The experimental room was dark during all food and drug sessions. Each food and drug session lasted for one hour or until 25 food pellets or 20 injections had been delivered. Monkeys could earn a maximum of 100 food pellets per day and 80 injections per day.

Drug Self-Administration Procedures

All monkeys were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.032 mg/kg/inj, i.v.) and subsequently given access to speedball combinations of cocaine and heroin. During speedball self-administration, cocaine and heroin were prepared in a single solution and delivered through one catheter lumen as in our previous studies (Mello and Negus 1998, 1999; Mello et al. 1995). Each cocaine or speedball injection was delivered in a volume of 0.10 ml over 1 sec. The simultaneous administration of cocaine and heroin combinations was designed to simulate one type of speedball self-administration reported by humans (Schütz et al. 1994).

Heroin and Cocaine (Speedball) Dose Combinations

The speedball combination selected for our initial studies consisted of 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine in combination with 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin. In our previous studies, these unit doses of cocaine alone and heroin alone each maintained high rates of drug self-administration at or near the peak of the cocaine and heroin dose-effect curves (Mello and Negus 1998; Mello et al. 1995). Our rationale for selecting a 3:1 ratio of cocaine to heroin was based on preliminary studies in which unit doses of 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine and 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin alone were the lowest doses that reliably maintained drug self-administration in all monkeys under these experimental conditions. Thus, cocaine was approximately 3-fold less potent than heroin as a reinforcer in rhesus monkeys.

Indatraline, Buprenorphine, and Saline Administration Procedures

Saline, indatraline, and buprenorphine alone, and indatraline and buprenorphine in combination, were administered by slow infusion (0.10 ml/min) in a volume of 5 ml through one lumen of the double lumen catheter from 9:30 to 10:20 each morning. These procedures were identical to those used in our previous studies of indatraline's effects on cocaine self-administration (Negus et al. 1999), buprenorphine's effects on cocaine self-administration (Mello et al. 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993a,b), and buprenorphine's effects on heroin and speedball self-administration (Mello and Negus 1998). For the remaining 23 hr of each experimental day, 0.10 ml saline were delivered every 20 min to maintain catheter patency.

Sequence of Indatraline + Buprenorphine Treatment Conditions

The effects of daily treatment with saline or indatraline and buprenorphine alone or in combination on speedball- and food-maintained responding were studied. Each treatment condition was in effect for 10 days to evaluate the time course of any effects observed (see Mello and Negus 1996 for discussion). At the end of each treatment condition, monkeys were returned to saline control treatment and the maintenance dose of cocaine for at least four days and until responding for cocaine and food returned to baseline levels. This interval of saline treatment was designed to prevent any effects of one treatment condition from influencing the effects of a subsequent treatment condition. Cocaine (0.032 mg/kg/inj) was used as the maintenance drug to ensure high baseline rates of drug-maintained responding before each treatment condition began. The same procedures were used in our previous reports of treatment medication effects on speedball self-administration (Mello and Negus 1998, 1999). Speedball combinations were substituted for the maintenance dose of cocaine in an irregular order.

In Experiment 1, the effects of indatraline alone, buprenorphine alone, and indatraline + buprenorphine combinations on responding maintained by food and a single dose of speedball (0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin) were examined in five monkeys. Indatraline + buprenorphine were administered in combinations consisting of a 3:1 ratio of indatraline to buprenorphine (0.10 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.032 mg/kg/day buprenorphine to 0.56 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine). These relative and absolute doses of indatraline + buprenorphine were based on our previous studies that examined the potency of indatraline in decreasing cocaine self-administration (Negus et al. 1999) and the potency of buprenorphine in decreasing heroin self-administration in rhesus monkeys (Mello and Negus 1998). The effects of the highest doses of indatraline alone (0.32–0.56 mg/kg/day) and buprenorphine alone (0.18 mg/kg/day) on speedball self-administration were also examined.

In Experiment 2, a dose-effect curve for speedball self-administration was determined. The speedball dose-effect curve consisted of the following cocaine and heroin combinations: 0.001 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.00032 mg/kg/inj heroin; 0.0032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.001 mg/kg/inj heroin; 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin; 0.032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.01 mg/kg/inj heroin. Each speedball dose combination was studied for 10 days during saline treatment. Then, the effects of treatment with combinations of indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) on the speedball dose-effect curve were evaluated in three monkeys in an own-control design. Each of three speedball dose combinations (0.001 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.00032 mg/kg/inj heroin; 0.0032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.001 mg/kg/inj heroin; 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin) was available for 10 days during indatraline + buprenorphine treatment.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl, heroin (3,6-diacetylmorphine HCl), and buprenorphine HCl were obtained in crystalline form from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH. The purity of cocaine and heroin was certified by Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, to be greater than 98%. Indatraline HCl (also known as Lu19-005) was purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA). All drugs were dissolved in sterile saline or sterile water, filter-sterilized using a 0.22 micron Millipore filter, and stored in sterile, pyrogen-free vials. All doses are expressed for the salt forms of the drugs described above.

Data Analysis

The dependent variables were the number of saline or speedball injections per day and the number of food pellets per day. Statistical analyses were based on the mean (± S.E.M.) number of injections and food pellets per day delivered over the entire 10 days of each treatment condition. Changes in drug- and food-maintained responding during treatment with indatraline and buprenorphine administered alone or in combination were statistically compared with the saline treatment baseline with an ANOVA for repeated measures and Contrast tests or Fishers post-hoc tests. Huynh-Feldt Epsilon factors were used to adjust for degrees of freedom of within-group means (Super ANOVA Software Manual, Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA; 1989). In addition, the mean numbers of injections and food pellets delivered each day during a 10-day medication or saline treatment condition are shown graphically for each speedball combination. Daily patterns of speedball- and food-maintained responding were compared with ANOVA for repeated measures on corresponding days during saline treatment and indatraline + buprenorphine treatment.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Effects of 10 Days Indatraline + Buprenorphine Treatment on Speedball- and Food-Maintained Responding

Figure 1 shows the effects of 10 consecutive days of treatment with saline, combinations of indatraline + buprenorphine, and indatraline and buprenorphine alone on speedball- (row 1) and food-maintained responding (row 2). During the saline baseline treatment, monkeys self-administered an average of 71 (±4) (mean ± S.E.M.) speedball injections per day and 61 (±7) (mean ± S.E.M.) food pellets per day. Treatment with a combination of 0.10 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.032 mg/kg/day buprenorphine produced no change in speedball-maintained responding and an increase in food-maintained responding. When 0.32 mg/kg/day indatraline was administered in combination with 0.10 mg/kg/day buprenorphine, speedball injections decreased significantly in comparison to saline treatment baseline levels (p < .01).

Effects of 10 days of treatment with saline, ascending doses of indatraline + buprenorphine combinations, and indatraline or buprenorphine alone on speedball- and food-maintained responding. Speedball- and food-maintained responding are shown as open rectangles during saline treatment, as closed rectangles during treatment with indatraline + buprenorphine combinations, as grey rectangles during treatment with indatraline alone and as a striped rectangle during treatment with buprenorphine alone. Saline and doses of indatraline and buprenorphine (mg/kg/day) are shown on the abscissae. The average number of speedball injections per day (row 1) or food pellets per day (row 2) are shown on the left ordinates. Speedballs consisted of a unit dose of cocaine (0.01 mg/kg/inj) and heroin (0.0032 mg/kg/inj) in combination. Each data point represents the average number of injections or food pellets (± S.E.M.) during 10 consecutive days of saline or drug treatment in a group of four or five monkeys (left panel), or three monkeys (right panel). The asterisks indicate a significant change from the saline treatment baseline (* = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001).

Food-maintained responding also decreased, but this change was not significantly different from saline treatment baseline levels. When 0.056 mg/kg/day indatraline was given in combination with 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine, speedball and food self-administration both decreased significantly in comparison to the saline treatment baseline (p < .05–.001). In contrast, when the same doses of indatraline alone (0.32 or 0.056 mg/kg/day) or buprenorphine alone (0.18 mg/kg/day) were administered, speedball and food self-administration did not decrease significantly relative to saline treatment baseline levels. Although speedball-maintained responding was higher during treatment with 0.32 mg/kg/day indatraline alone and 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine alone than during combined indatraline and buprenorphine treatment, these differences were not statistically significant. Food-maintained responding did not differ significantly from the saline treatment baseline during treatment with indatraline alone and tended to increase during treatment with buprenorphine alone.

Figure 2 shows the average number of speedball injections and food pellets delivered each day during the 10 days of treatment with saline, or combinations of indatraline (0.10, 0.32, 0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.032, 0.10, 0.18 mg/kg/day). During saline treatment, speedball-maintained responding averaged between 66 ± 5 and 78 ± 2 injections per day and food-maintained responding averaged between 53 ± 7 and 68 ± 13 pellets per day. Patterns of both speedball- and food-maintained responding were relatively stable across the 10 days of saline treatment. Speedball- and food-maintained responding during saline treatment were compared with corresponding days during treatment with indatraline + buprenorphine. When 0.10 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.032 mg/kg/day buprenorphine were administered in combination, there was an initial decrease in both speedball- and food-maintained responding that was not sustained.

Effects of chronic treatment with saline or indatraline + buprenorphine combinations on daily speedball- and food-maintained responding. Consecutive days of treatment are shown on the abscissae. Speedball injections per day are shown on the left ordinate and food pellets per day are shown on the right ordinate. Speedballs consisted of a unit dose of cocaine (0.01 mg/kg/inj) and heroin (0.0032 mg/kg/inj) in combination. Average speedball and food self-administration per day (± S.E.M.) during 10 days of saline treatment are shown as open circles and during combined indatraline + buprenorphine treatment are shown as closed symbols. Indatraline + buprenorphine doses are shown as follows: closed triangles, 0.10 + 0.032 mg/kg/day; closed squares, 0.32 + 0.10 mg/kg/day; closed circles, 0.56 + 0.18 mg/kg/day. Each data point is based on four or five monkeys.

Food-maintained responding gradually increased and was significantly higher on days 4-10 than on corresponding days during the saline treatment baseline (p < .05–.001). A higher dose of 0.32 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine reduced both speedball- and food-maintained responding significantly below saline treatment levels (p < .05–.001). The decreases in speedball-maintained responding were sustained throughout the 10-day treatment period, but food-maintained responding returned to baseline levels after two days. At the highest dose studied (0.56 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine), speedball- and food-maintained responding decreased significantly below baseline throughout the 10-day treatment period (p <.05–.001). After two days of indatraline + buprenorphine treatment, speedball self-administration decreased to 0 injections per day in two monkeys. After five days of indatraline + buprenorphine treatment, speedball self-administration decreased to between 0 and 5 injections per day in four of the five monkeys studied.

Experiment 2: Effects of 10 Days of Treatment with Indatraline + Buprenorphine Combinations on the Speedball Dose-Effect Curve

Saline Treatment

Figure 3 shows the effects of treatment with saline or with a combination of indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) and buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) on the speedball dose-effect curve [left panel] and concurrent food-maintained responding [right panel]. During saline treatment, when saline was available for self-administration, monkeys took an average of 20 ± 4 (mean ± S.E.M.) injections per day and 87 ± 7 (mean ± S.E.M.) food pellets per day. When a 3:1 cocaine/heroin speedball combination was available during saline control treatment, the speedball dose-effect curve had an inverted-U shape. Speedball doses of 0.0032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.001 mg/kg/inj heroin to 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin each maintained significantly more responding than saline (p < .05–.001). A unit dose of 0.0032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.001 mg/kg/inj heroin was at the peak of the speedball dose-effect curve and maintained 74 ± 4 (mean ± S.E.M.) speedball injections per day. During saline treatment, there was a speedball dose-dependent decrease in food-maintained responding. At the highest speedball doses (0.32 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.01 mg/kg/inj heroin), food-maintained responding was significantly below levels during saline self-administration (p < .05).

Effects of 10 days of treatment with saline or an indatraline + buprenorphine combination on speedball dose-effect curves. Dose-effect curves for speedball combinations of cocaine (0.001–0.10 mg/kg/inj) and heroin (0.00032–0.032 mg/kg/inj) are shown for a group of three monkeys (left panel). The unit doses of each cocaine and heroin combination are shown on the abscissa. Injections per day are shown on the left ordinate. Points above “Saline” show data from saline treatment sessions when saline was the solution available for self-administration. Self-administration of each cocaine-heroin combination during saline treatment (open circles) is shown at the left. Speedball self-administration during treatment with an indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) combination is shown as black circles. Each data point is the average of 10 days of speedball or food self-administration (± S.E.M.). Food-maintained responding during saline self-administration and self-administration of speedball cocaine and heroin combinations during saline treatment (open circles) is shown in the right panel. The number of food pellets self-administered per day is shown on the right ordinate. Food-maintained responding during treatment with indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) is shown as black circles. The daggers indicate a significant difference from saline self-administration during saline treatment († = p <.05; †† = p < .01). The asterisks indicate that the number of speedball injections self-administered at the same speedball dose combinations were significantly different during saline treatment and indatraline + buprenorphine treatment (** = p < .01).

Indatraline + Buprenorphine Treatment

Treatment with the 0.56 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine combination produced a downward shift in the peak of the speedball self-administration dose-effect curve. The two speedball unit doses that were at the peak of the dose-effect curve during saline treatment maintained significantly lower levels of speedball self-administration during indatraline + buprenorphine treatment (p < .02). Moreover, responding for these two speedball doses during indatraline + buprenorphine treatment was equivalent to or lower than saline-maintained responding during saline treatment. Food-maintained responding during treatment with indatraline + buprenorphine did not differ significantly from levels of food-maintained responding during saline treatment. There was a similar speedball dose-dependent decrease in the average number of food pellets per day during indatraline + buprenorphine and saline treatment.

Figure 4 shows daily patterns of speedball- and food-maintained responding during 10 days of treatment with saline or a combination of 0.56 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.18 mg/kg/day buprenorphine. The two speedball doses are from the ascending limb of the speedball dose-effect curve shown in Figure 3. During saline treatment, the lowest speedball dose studied (0.001 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.00032 mg/kg/inj) did not maintain responding significantly above saline levels. Figure 4 shows that speedball-maintained responding decreased from 69 ± 7 injections on day 1 to 26 ± 7 injections on day 10 (row 1, left panel). During treatment with indatraline + buprenorphine, speedball injections were significantly lower than during saline treatment on days 1, 3, 4, and 6 (p < .05). Speedball self-administration decreased to 1 injection per day by the third day of treatment and remained low throughout the remainder of the treatment period (Figure 4, row 1, left panel). During saline treatment, food-maintained responding averaged between 85 and 93 pellets per day (Figure 4, row 1, right panel). On the first day of indatraline + buprenorphine treatment, food-maintained responding was significantly below saline treatment levels (p < .05). After five days of treatment, food-maintained responding gradually returned to baseline levels (Figure 4, row 1, right panel).

Effects of chronic treatment with saline and an indatraline + buprenorphine combination on daily speedball- and food-maintained responding. The unit doses of each cocaine and heroin speedball combination are shown in the grey boxes in the center of each row. Speedball injections per day are shown on the left ordinate and food pellets per day are shown on the right ordinate. Speedball-maintained responding during 10 days of saline treatment is shown as open circles. Speedball-maintained responding during 10 days of indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) treatment is shown as closed circles (left panel). Food-maintained responding during 10 days of saline treatment is shown as open squares. Food-maintained responding during 10 days of indatraline (0.56 mg/kg/day) + buprenorphine (0.18 mg/kg/day) treatment is shown as closed squares (right panel). Consecutive days of treatment are shown on the abscissae. Each data point is based on the same three monkeys studied as their own control across treatment conditions. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in speedball- or food-maintained responding on corresponding days during saline treatment and indatraline + buprenorphine treatment (* = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001).

Responding maintained by 0.0032 mg/kg/inj cocaine + 0.001 mg/kg/inj heroin, the speedball dose that was at the peak of the dose-effect curve, varied between 80 and 62 injections per day during saline treatment (Figure 4, row 2, left panel). Speedball-maintained responding decreased significantly below saline treatment levels on the first day of indatraline + buprenorphine treatment (p < .001) and remained significantly below saline treatment levels for 10 days (p < .001) (Figure 4, row 2, left). Food-maintained responding was also significantly below saline treatment baseline levels for the first three days of indatraline + buprenorphine treatment (p < .01–.001), then gradually returned towards baseline levels (Figure 4, row 2, right panel).

Other Effects of Chronic Indatraline and Buprenorphine Treatment

Chronic administration of indatraline alone and the highest doses of indatraline + buprenorphine was associated with some hyperactivity (stereotypic grooming, scratching, visual checking) in all five monkeys. No sedation or hyperactivity was observed during treatment with buprenorphine alone or lower doses of indatraline + buprenorphine combinations (0.10 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.032 mg/kg/day buprenorphine to 0.32 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.10 mg/kg/day buprenorphine).

DISCUSSION

Effects of Indatraline + Buprenorphine Combinations on Speedball Self-Administration

Although cocaine and opioids produce some interacting effects, the abuse-related effects of cocaine and opioids appear to remain functionally independent of each other when combined in a speedball (Hemby et al. 1996, 1999; Mello and Negus 1999; Negus et al. 1998a). Accordingly, we hypothesized that a combination of medications targeted at both the stimulant and opioid components of the speedball might be effective in attenuating the reinforcing effects of this type of multiple drug self-administration (Mello and Negus 1999).

This is the first evaluation of the combined effects of two potential agonist substitution medications, the dopamine reuptake inhibitor indatraline and the mu opioid partial agonist buprenorphine, on speedball (cocaine + heroin) self-administration by rhesus monkeys. Our major finding was that chronic administration of an indatraline + buprenorphine combination produced significant and sustained decreases in self-administration of speedballs at the peak of the dose-effect curve. Moreover, an indatraline + buprenorphine combination produced a significant downward shift in the speedball self-administration dose-effect curve. In contrast, 10 days of treatment with the same doses of indatraline alone and buprenorphine alone did not reduce speedball self-administration significantly. Indatraline + buprenorphine combinations also did not increase self-administration of speedballs that maintained low rates of responding during saline control treatment. These data suggest that indatraline + buprenorphine combinations did not enhance the reinforcing efficacy of low doses of speedballs, but rather reduced the reinforcing effects of speedballs across a broad dose range.

These findings are consistent with our earlier reports that pretreatment with combinations of a non-selective dopamine antagonist flupenthixol and an opioid antagonist quadazocine dose-dependently antagonized both the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of speedballs, whereas administration of the same doses of flupenthixol alone or quadazocine alone was less effective (Mello and Negus 1999; Negus et al. 1998a). Speedball self-administration was maintained by a 3:1 cocaine-heroin combination in that study (Mello and Negus 1999) and in the present study. However, the effects of indatraline + buprenorphine combinations on speedball self-administration in the present study differed from those of flupenthixol + quadazocine in our previous study in several respects (Mello and Negus 1999). First, the effects of indatraline + buprenorphine on speedball-maintained responding were usually sustained across 10 days of treatment, whereas the effects of flupenthixol + quadazocine were usually transient (Mello and Negus 1999). Sustained reductions in the self-administration of cocaine alone have been observed for periods up to four months during buprenorphine treatment (Mello et al. 1992) and for up to seven days (the longest period evaluated) during treatment with indatraline alone (Negus et al. 1999). The transient effects of the flupenthixol + quadazocine combination probably reflect the fact that dopamine antagonists often have transient effects on cocaine self-administration alone (Kleven and Woolverton 1990; Negus et al. 1996; Richardson et al. 1994).

A second major difference between the effects of treatment with indatraline + buprenorphine combinations and flupenthixol + quadazocine combinations on speedball-maintained responding was in the direction of changes in the speedball dose-effect curve. Flupenthixol + quadazocine treatment produced a 3-fold rightward shift in the speedball dose-effect curve and slightly increased self-administration of high speedball doses (Mello and Negus 1999). In contrast, indatraline + buprenorphine decreased speedball self-administration across the range of speedball doses examined. We have suggested elsewhere that a downward shift in a drug self-administration dose-effect curve may have the greatest therapeutic utility, because there is a decrease in drug-taking behavior across a broad range of unit doses (Mello and Negus 1996). In contrast, medications that produce a rightward shift in the drug dose-effect curve simply alter the potency of the abused drug. Thus, increases in the unit dose of the abused drug, or increases in the rate of drug self-administration, could negate the effect of the medication on drug-maintained responding (Mello and Negus 1996). The effects of indatraline + buprenorphine on self-administration of high speedball doses on the descending limb of the speedball dose-effect curve were not examined in the present study. However, it is likely that indatraline + buprenorphine would also have decreased high dose speedball self-administration because indatraline decreases high dose cocaine self-administration and buprenorphine decreases high dose heroin self-administration (Mello and Negus 1998; Negus et al. 1999).

A third difference between the behavioral effects of indatraline + buprenorphine combinations and the flupenthixol + quadazocine combinations was in the type and severity of adverse side effects produced during chronic treatment. Indatraline + buprenorphine produced hyperactivity reflected in stereotypic grooming, scratching and visual checking; behaviors similar to those previously observed during chronic treatment with indatraline alone (0.32–1.0 mg/kg/day) (Negus et al. 1999). In contrast, flupenthixol + quadazocine produced transient mild sedation reflected in decreased locomotor activity and unresponsiveness to preferred foods (Mello and Negus 1999). Sedation usually accompanies administration of dopamine antagonists to rhesus monkeys (Negus et al. 1996; Winger 1994; see Mello and Negus 1996 for review). The implications of these adverse side effects for the clinical treatment of polydrug abuse remain to be determined.

Effects of Indatraline and Buprenorphine on Food-Maintained Responding

Treatment with 0.32 mg/kg/day indatraline + 0.10 mg/kg/day buprenorphine selectively decreased speedball self-administration with no significant decrease in food-maintained responding, whereas a higher dose of indatraline + buprenorphine decreased both speedball- and food-maintained responding. However, decreases in food-maintained responding were usually transient and began to return toward baseline levels after five days of treatment whereas decreases in speedball-maintained responding were sustained. These findings suggest that indatraline + buprenorphine combinations selectively decreased speedball self-administration. However, interpretation of the relative selectivity of indatraline + buprenorphine effects on speedballs and food is complicated by the fact that there was also a speedball dose-dependent decrease in food-maintained responding during saline treatment. These results are consistent with our previous reports that self-administration of various speedball combinations, as well as cocaine alone and heroin alone, produced dose-dependent decreases in food-maintained responding under experimental conditions identical to those reported here (Mello and Negus 1998; Mello et al. 1995; Negus et al. 1995). Although indatraline + buprenorphine treatment appeared to reduce the reinforcing effects of speedballs, it did not significantly alter the direct rate-decreasing effects of speedballs on food-maintained responding.

We previously reported that treatment with a flupenthixol + quadazocine combination also did not attenuate speedball-induced decreases in food-maintained responding (Mello and Negus 1999). However, quadazocine appeared to antagonize the rate-decreasing effects of the heroin component of the speedball, because the highest rates of food-maintained responding were observed during treatment with quadazocine alone (Mello and Negus 1999). In the present study, buprenorphine also appeared to antagonize the rate-decreasing effects of heroin because food-maintained responding was highest during treatment with buprenorphine alone. Similarly, chronic treatment with buprenorphine alone often attenuated the rate-decreasing effects of heroin and speedball self-administration on food-maintained responding (Mello and Negus 1998). Taken together, these findings suggest that opioid partial agonists and antagonists readily antagonize the rate-decreasing effects of opioid agonists, whereas dopamine reuptake inhibitors and dopamine antagonists are less effective in blocking the rate-decreasing effects of cocaine and may also produce rate-decreasing effects of their own (Mello and Negus 1998, 1999; Negus et al. 1999; see Mello and Negus 1996 for review).

Effects of Indatraline and Buprenorphine Alone on Speedball Self-Administration

Indatraline alone did not significantly reduce speedball-maintained responding, whereas in our previous study, indatraline produced dose-dependent and sustained decreases in cocaine self-administration across a broad range of cocaine doses (Negus et al. 1999). Moreover, indatraline produced downward shifts in cocaine self-administration dose-effect curves (Negus et al. 1999). Indatraline is a relatively non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitor (Bogeso et al. 1985; Hyttel and Larsen 1985), and it is possible that more selective dopamine reuptake inhibitors in combination with buprenorphine might be even more effective in reducing speedball self-administration. For example, it has been reported that more selective dopamine reuptake inhibitors produce downward shifts in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve with minimal effects on food-maintained responding (Dworkin et al. 1998; Glowa et al. 1995a,b, 1996). However, dopamine reuptake inhibitors also produce non-selective behavioral effects such as hyperactivity and stereotypies, which may decrease operant responding maintained by both drug and non-drug reinforcers (Negus et al. 1999). These non-selective behavioral effects may have contributed to the reductions in speedball self-administration observed at the beginning of indatraline treatment. We are unaware of any studies of the effects of dopamine reuptake inhibitors on opioid self-administration.

In our previous studies, buprenorphine alone reduced cocaine self-administration (Mello et al. 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993a,b) as well as opioid self-administration (Mello et al. 1983; Mello and Negus 1998) under the same schedule of reinforcement and sequence of daily drug and food sessions as in the present study. However, buprenorphine alone (0.18 mg/kg/day) did not reduce responding maintained by a speedball combination of 0.01 mg/kg/inj cocaine and 0.0032 mg/kg/inj heroin in the present study. These data are consistent with our previous report that buprenorphine (0.075 or 0.75 mg/kg/day) also did not decrease self-administration of the same speedball cocaine + heroin dose combination (Mello and Negus 1998). As noted earlier, chronic treatment with buprenorphine alone (0.237 mg/kg/day) shifted dose-effect curves for speedball combinations of cocaine (0.001 mg/kg/inj) and heroin (0.0001–0.032 mg/kg/inj) downwards and approximately 1 log unit to the right (Mello and Negus 1998). However, the same dose of buprenorphine was less effective in decreasing responding maintained by speedball combinations of heroin (0.0001–0.10 mg/kg/inj) and higher doses of cocaine (0.01 and 0.1 mg/kg/inj) (Mello and Negus 1998).

Implications for Polydrug Abuse Treatment

The reinforcing and the discriminative stimulus effects of speedballs appear to reflect some aspects of both the opioid and stimulant component drugs. Our finding that speedball self-administration was reduced more effectively by a combination of indatraline and buprenorphine doses than by either drug dose alone confirms and extends our previous finding with flupenthixol and quadazocine (Mello and Negus 1999). Taken together, these data suggest that medications targeted at the cocaine and heroin components of the speedball may reduce speedball self-administration with higher potency or greater efficacy when they are administered in combination than when they are administered alone. This approach is consistent with the fact that cocaine and opioid components are primarily mediated by different receptor mechanisms. The contribution of dopaminergic activity to the abuse-related effects of cocaine is well documented (Koob and Bloom 1988; Kuhar et al. 1991; Ritz et al. 1987; Woolverton and Johnson 1992) but dopamine's role in the reinforcing effects of opioids has not been clearly established (Hemby et al. 1995, 1999). Similarly, mu opioid receptor activity is important for the reinforcing effects of opioids, but not of cocaine (Negus and Dykstra 1989).

Studies with receptor-selective antagonists indicate that dopamine antagonists usually alter the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine but not of opioids, whereas mu opioid antagonists alter the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of opioids but not of cocaine (Mello et al. 1995; Negus et al. 1996; Platt et al. 1999; see Mello and Negus 1996 for review). The present study indicates that combinations of drugs with primarily dopaminergic or mu opioid activity are relatively effective in reducing speedball self-administration. These data encourage further exploration of medication combinations as a new strategy for polydrug abuse treatment.

References

Bogeso KP, Christensen AV, Hyttel J, Liljefors T . (1985): 3 Phenyl-1-indanamines: Potential antidepressant activity and potent inhibition of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin uptake. J Med Chem 28: 1817–1828

Condelli WS, Fairbank JA, Dennis ML, Rachal JV . (1991): Cocaine use by clients in methadone programs: Significance, scope, and behavioral interventions. J Subst Abuse Treat 8: 203–212

Corrigall WA, Coen KM . (1991): Cocaine self-administration is increased by both D1 and D2 dopamine antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 39: 799–802

Dworkin SI, Lambert P, Sizemore GM, Carroll FI, Kuhar MJ . (1998): RTI-113 administration reduces cocaine self-administration at high occupancy of dopamine transporter. Synapse 30: 49–55

Foltin RW, Christiansen I, Levin FR, Fischman MW . (1995): Effects of single and multiple intravenous cocaine injections in humans maintained on methadone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275: 38–47

Foltin RW, Fischman MW . (1992): The cardiovascular and subjective effects of intravenous cocaine and morphine combinations in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 261: 623–632

Gastfriend DR, Mendelson JH, Mello NK, Teoh SK, Reif S . (1993): Buprenorphine pharmacotherapy for concurrent heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Addict 2: 269–278

Glowa JR, Wojinicki FHE, Matecka D, Rice KC, Rothman RB . (1996): Sustained decrease in cocaine-maintained responding in rhesus monkeys with 1-[2-[bis (4-fluorophenyl)methoxy]ethyl]-4-(3-hydroxy-3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropyl) piperaxinyl decanoate, a long-acting ester derivative of GBR 12909. J Med Chem 39: 4628–4691

Glowa JR, Wojnicki FHE, Matecka D, Bacher JD, Mansbach RS, Balster RL, Rice KC . (1995a): Effects of dopamine reuptake inhibitors on food- and cocaine-maintained responding. I. Dependence on unit dose of cocaine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 3: 219–231

Glowa JR, Wojnicki FHE, Matecka D, Rice KC, Rothman RB . (1995b): Effects of dopamine reuptake inhibitors on food- and cocaine-maintained responding. II. Comparisons with other drugs and repeated administrations. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 3: 232–239

Hemby SE, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE . (1999): Synergistic elevations in nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine concentrations during self-administration of cocaine/heroin combinations (Speedball) in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288: 274–280

Hemby SE, Martin TJ, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE . (1995): The effects of intravenous heroin administration on extracellular nucleus accumbens dopamine concentrations as determined by in vivo microdialysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273: 591–598

Hemby SE, Smith JE, Dworkin SI . (1996): The effects of eticlopride and naltrexone on responding maintained by food, cocaine, heroin and cocaine/heroin combinations in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277: 1247–1258

Hyttel J, Larsen JJ . (1985): Neurochemical profile of Lu 19-005, a potent inhibitor of uptake of dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin. J Neurochem 44: 1615–1622

ILAR-NRC. (1996): Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC, National Academy Press

Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ . (1992): A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. J Am Med Assoc 267: 2750–2755

Kleven MS, Koek W . (1998): Discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine: Enhancement by monoamine reuptake blockers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 284: 1015–1025

Kleven MS, Woolverton WL . (1990): Effects of continuous infusions of SCH 23390 on cocaine- or food-maintained behavior in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 1: 365–373

Koob GF, Bloom FE . (1988): Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science 242: 715–723

Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C . (1989a): Role of opioid antagonists in treating intravenous cocaine abuse. Life Sci 44: 887–892

Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C . (1989b): Treatment of cocaine abuse with buprenorphine. Biol Psychiatry 26: 170–172

Kuhar MJ, Ritz MC, Boja JW . (1991): The dopamine hypothesis of the reinforcing properties of cocaine. Trends Neurosci 14: 299–302

Line SW . (1987): Environmental enrichment for laboratory primates. JAMA 90: 854–859

Mello NK, Bree MP, Mendelson JH . (1983): Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone effects on opiate self-administration in primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 225: 378–386

Mello NK, Kamien JB, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH, Drieze JM, Sholar JW . (1993a): Effects of intermittent buprenorphine administration on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264: 530–541

Mello NK, Lukas SE, Kamien JB, Mendelson JH, Drieze J, Cone EJ . (1992): The effects of chronic buprenorphine treatment on cocaine and food self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 260: 1185–1193

Mello NK, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH, Drieze J . (1993b): Naltrexone-buprenorphine interactions: Effects on cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 9: 211–224

Mello NK, Mendelson JH . (1980): Buprenorphine suppresses heroin use by heroin addicts. Science 27: 657–659

Mello NK, Mendelson JH . (1995): Buprenorphine treatment of cocaine and heroin abuse. In Cowan A, Lewis JW (eds), Buprenorphine: Combating Drug Abuse with a Unique Opioid. New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp 243–287

Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Lukas SE . (1989): Buprenorphine suppresses cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkey. Science 245: 859–862

Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Lukas SE . (1990): Buprenorphine and naltrexone effects on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 254: 926–939

Mello NK, Negus SS . (1996): Preclinical evaluation of pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine and opiate abuse using drug self-administration procedures. Neuropsychopharmacology 14: 375–424

Mello NK, Negus SS . (1998): The effects of buprenorphine on self-administration of cocaine and heroin “speedball” combinations and heroin alone by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285: 444–456

Mello NK, Negus SS . (1999): Effects of flupenthixol and quadazocine on self-administration of speedball combinations of cocaine and heroin by rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 21: 575–588

Mello NK, Negus SS, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH, Sholar JW, Drieze J . (1995): A primate model of polydrug abuse: Cocaine and heroin combinations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274: 1325–1337

Mendelson JH, Mello NK . (1996): Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. N Engl J Med 334: 965–972

National Research Council Committee on Clinical Evaluation of Narcotic Antagonists. (1978): Clinical evaluation of naltrexone treatment of opioid-dependent individual. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35: 335–340

Negus SS, Brandt MR, Mello NK . (1999): Effects of the long-acting monoamine reuptake inhibitor indatraline on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 60–69

Negus SS, Dykstra LA . (1989): Neural substrates mediating the reinforcing properties of opioid analgesics. In Watson RW (ed), Biochemistry and Physiology of Substance Abuse, Vol. 1. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, pp 211–242

Negus SS, Gatch MB, Mello NK . (1998a): Discriminative stimulus effects of a cocaine/heroin “speedball” combination in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285: 1123–1136

Negus SS, Mello NK, Lamas X, Mendelson JH . (1996): Acute and chronic effects of flupenthixol on the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278: 879–890

Negus SS, Mello NK, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH . (1995): Diurnal patterns of cocaine and heroin self-administration in rhesus monkeys responding under a schedule of multiple daily sessions. Behav Pharmacol 6: 763–775

NIDA. (1999): Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse, NIH Publication No. 00–4529. National Institute on Drug Abuse, pp 187

O'Brien CP . (1996): Drug addiction and drug abuse. In Goodman and Gilman (eds), The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York, McGraw Hill Co., pp 557–577

Platt DM, Grech DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD . (1999): Discriminative stimulus effects of morphine in squirrel monkeys: Stimulants, opioids, and stimulant-opioid combinations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 1092–1100

Preston KL, Sullivan JT, Strain EC, Bigelow GE . (1996): Enhancement of cocaine's abuse liability in methadone maintenance patients. Psychopharmacology 123: 15–25

Richardson NR, Smith AM, Roberts DCS . (1994): A single injection of either flupenthixol decanoate or haloperidol decanoate produces long-term changes in cocaine self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Dep 36: 23–25

Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ . (1987): Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237: 1219–1223

Rothman RB, Glowa JR . (1995): A review of the effects of dopaminergic agents on humans, animals, and drug-seeking behavior, and its implications for medication development: Focus on GBR 12909. Molecular Neurobiology 10: 1–19

Rowlett JK, Spealman RD . (1998): Opioid enhancement of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine: Evidence for involvement of μ and δ opioid receptors. Psychopharmacology 140: 217–224

Rowlett JK, Wilcox KM, Woolverton WL . (1998): Self-administration of cocaine-heroin combinations by rhesus monkeys: Antagonism by naltrexone. J Pharm Exp Ther 286: 61–69

Rowlett JK, Woolverton WL . (1997): Self-administration of cocaine and heroin combinations by rhesus monkeys responding under a progressive-ratio schedule. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 133: 363–371

Schecter A . (1980): The role of narcotic antagonists in the rehabilitation of opiate addicts: A review of naltrexone. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 7: 1–18

Schottenfeld RS, Pakes J, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR . (1993): Buprenorphine: Dose-related effects on cocaine and opioid use in cocaine-abusing opioid-dependent humans. Biol Psychiatry 3: 66–74

Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR . (1997): Buprenorphine vs. methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 713–720

Schütz CG, Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Graham NMH . (1994): Comparison of self-reported injection frequencies for past 30 days and 6 months among intravenous drug users. J Clin Epidemiol 47: 191–195

Spealman RD, Bergman J . (1992): Modulation of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine by mu and kappa opioids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 261: 607–615

Spealman RD, Bergman J . (1994): Opioid modulation of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine: Comparison of μ, κ and δ; agonists in squirrel monkeys discriminating low doses of cocaine. Behav Pharmacol 5: 21–31

Walsh SL, Sullivan JT, Preston KL, Garner J . (1996): The effects of naltrexone on response to i.v. cocaine, hydromorphone and their combination in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279: 524–538

Winger G . (1994): Dopamine antagonist effects on behavior maintained by cocaine and alfentanil in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 5: 141–152

Woolverton WL, Johnson KM . (1992): Neurobiology of cocaine abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci 13: 193–200

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicolas Diaz-Migoyo, Ashton Koo, and Rebecca Callahan for their technical assistance. We are grateful to Beth Moseley, D.V.M., for veterinary assistance and to Bruce Stephen for his contributions to the data analysis. Preliminary data were reported at the 1999 annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. This research was supported in part by KO5 DA-00101, P50 DA-04059, and RO1 DA-02519 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mello, N., Negus, S. Effects of Indatraline and Buprenorphine on Self-Administration of Speedball Combinations of Cocaine and Heroin by Rhesus Monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacol 25, 104–117 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00247-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00247-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of d-Amphetamine and Buprenorphine Combinations on Speedball (Cocaine+Heroin) Self-Administration by Rhesus Monkeys

Neuropsychopharmacology (2007)

-

Agonist-Like or Antagonist-Like Treatment for Cocaine Dependence with Methadone for Heroin Dependence: Two Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials

Neuropsychopharmacology (2004)

-

Second-order stimuli do not always increase overall response rates in second-order schedules of reinforcement in the rat

Psychopharmacology (2004)