Abstract

The weight-based definition of anorexia nervosa (AN) can result in heavier individuals being excluded from evidence-based interventions and erroneously included in practices with negative physical and psychological consequences. Our purpose was to address the AN weight criteria limitation by expanding upon the components of disordered eating underlying membership in weight categories that are considered unhealthy. In this cross-sectional study, 733 male and female participants completed online questionnaires assessing age, gender, BMI (height and weight), and disordered eating behaviours and attitudes. Participants were grouped according to their weight status (underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese). Results indicated that BMI was positively associated with many aspects of disordered eating but was inversely associated with restricting eating, excessive exercise, and muscle building in women. Underweight men and women reported similar levels of body dissatisfaction, but compared to men, the effect was much more pronounced in women as weight increased. Taken together, lighter-weight individuals reported higher levels of AN-specific behaviour (restricting eating) compared to heavier-weight participants. In contrast, heavier-weight individuals had higher AN-related attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours, such as body dissatisfaction, cognitive restraint, and binge eating. These results support that AN attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours can be found in individuals regardless of whether they are underweight or obese. Future research is needed to develop interventions addressing anorexic symptoms in people considered overweight or obese to meet their specific needs.

Plain English Summary

Heavier-weight individuals who experience anorexic cognitions, attitudes, and behaviours are often excluded from beneficial interventions. They have commonly directed treatment goals with negative physical and psychological consequences, such as losing weight. Our purpose was to address this limitation by expanding upon the disordered eating factors associated with being underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. Participants were administered online questionnaires. Overall, underweight participants had higher levels of anorexic-specific behaviour (restricting eating). In contrast, obese respondents had greater anorexic-related attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours, such as body dissatisfaction, cognitive restraint, and binge eating. These results support that AN attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours can be found in individuals regardless of whether they are underweight or obese. Future research is needed to develop interventions addressing anorexic symptoms in people considered overweight or obese to meet their specific needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Disordered eating is characterized by irregular eating attitudes and behaviours, which include, but are not limited to, clinical feeding and eating disorder diagnoses. Although the clinical diagnosis of an eating disorder, specifically anorexia nervosa (AN), has traditionally focused on having a dangerously low body weight, more recently, researchers and clinicians have recognized that individuals at all weights are at risk of eating disorders and high severity of disordered eating. Both underweight and overweight individuals are more likely to report disordered eating than normal-weight individuals [1]. Although heavier weight status is associated with a higher risk of binge eating [2], high prevalence rates of strict dieting (21%) and binge eating (52%) are reported by obese individuals [3]. Further, a 5-year longitudinal study concluded that youth reporting disordered eating behaviours, including fasting, using diet pills, or self-induced vomiting, were three times more likely to become overweight and were at an increased risk for binge eating [4]. Although a higher body mass index (BMI) significantly predicts restrained and emotional eating [5], these behaviours are often not recognized in larger individuals. Thus, this cross-sectional study aimed to explore whether AN attitudes and behaviours are similar in individuals in different weight categories.Traditionally, only underweight individuals were considered susceptible to anorexic attitudes and behaviours; for example, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), a BMI less than 17 kg/m2 was a requirement for AN diagnosis [6]. Other diagnostic criteria focuses on restricting behaviours and cognitions, body dissatisfaction, and binge eating and purging, which are considered only if the underweight status was met. Due to the strict criteria in previous versions of the DSM [7], the DSM-5 included a diagnostic category, “atypical AN,” that focuses on individuals who experience less frequent and severe AN symptoms, including an excessive fear of gaining weight (AN Criterion B) and body image disturbance (AN Criterion C), in addition to significant weight loss without meeting the low BMI criteria [8].

Recent research supports similarities and disparities in typical versus atypical AN. Important differences between the eating disorder diagnoses support using categorical models to conceptualize AN. A systematic review of 24 studies noted that atypical AN is more commonly found in men and non-White individuals [9]. This systematic review also indicated that, generally, eating disorder-related psychopathology, including eating, shape, and weight concerns, is more prevalent in individuals with atypical AN versus typical AN. Although individuals with typical and atypical AN experience menstrual disturbance, cardiac conditions, and hospitalizations, the severity was more significant in those meeting the typical criteria. Some researchers believe that the substantiated differences between typical and atypical AN are sufficient to warrant a categorical approach that distinguishes the two diagnoses [10].

In contrast, both diagnoses share similarities in terms of social factors; parents of AN and atypical AN patients often set examples of disordered eating behaviours [11]. Psychological factors, including obsessive–compulsive symptom frequency and severity, are proportionately reported by typical and atypical AN participants [12]. Both diagnoses include the DSM-5 criterion of engaging in excessive weight control behaviours [13], and despite having different body weights, both atypical and typical AN patients experience significant weight loss and can have similar medical outcomes [14]. In the above-mentioned systematic review [9], some comparisons were not statistically significant, including similar levels of non-eating disorder-related psychopathology (e.g. depression, anxiety). Despite the improvements in the DSM-5 and similarities between typical and atypical AN, the weight-based definition of AN excludes heavier-weight individuals from relevant interventions that address attitudes and behaviours typically associated with AN and can result in the denial of insurance coverage [11]. Simultaneously, larger individuals who experience AN behaviours but do not meet the weight criteria for diagnosis are as likely as underweight individuals to experience physical health limitations such as bradycardia (i.e. slower than average heart rate) and disturbances in their menstrual cycle [15]. Future research validating the relationship between AN attitudes and behaviours and heavier BMI status may broaden the perspectives of healthcare providers and stakeholders in addressing AN.

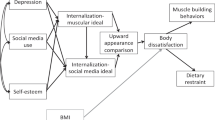

The DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses are biased towards women [16, 17]. The diagnostic criteria do not adequately represent males because the weight and shape concerns more commonly found in men are not properly included in the criteria for eating disorders [16, 18]. For example, body dissatisfaction among males is generally driven by the “muscular ideal” rather than the “thin ideal;” however, the drive for muscularity is not included in the criteria for eating disorder diagnoses in the DSM-5 [18]. Instead, the drive for muscularity falls under the “obsessive–compulsive and related disorders” category as “muscle dysmorphia.” Thus, rather than focusing on specific diagnostic criteria, a general methodological approach that more accurately encompasses eating pathology is the examination of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours indicative of particular symptoms [19].

Taken together, the lack of distinction between underweight and overweight individuals with anorexic attitudes and behaviours, which can lead to treatment practices causing counterproductive effects [20]. Using a categorical approach to eating pathology can result in excluding heavier-weight individuals with similar disordered eating patterns from research and treatment [11]. Thus, the primary purpose of this study was to examine attitudes and behaviours associated with disordered eating in a non-clinical sample of males and females who report being normal weight, underweight, overweight, and obese.

1 Methods

As increasing number of empirical studies support dimensional models in conceptualizing mental disorders, the DSM-V includes an emerging model of personality disorders, characterized as a hybrid dimensional-categorical model (Section III) [22]. The current study contributes to this movement by providing additional evidence for dimensional conceptualizations of eating disorders, specifically across the weight spectrum. Using comparative analyses to contrast the frequency and severity of AN attitudes and behaviours across weight categories while considering age and gender were central to the purpose of this study To ensure that our sample was representative of the wide range of AN presentations, a dimensional approach was used in which participants were contrasted based on varying levels of disordered eating; only weight was categorized using self-reported weight and height converted to BMI (BMI = kg/m2). Classification of BMI has been empirically supported as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI = 18.5–24.99 kg/m2), and overweight (BMI = 25–29.99 kg/m2), obese I (BMI = 30–34.99 kg/m2), obese II (BMI = 35–39.99 kg/m2), and obese III (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) [21].

To ensure that our sample was representative of the wide range of AN presentations, a dimensional approach was used in which participants were contrasted based on varying levels of disordered eating; only weight was categorized using self-reported weight and height converted to BMI (BMI = kg/m2). Classification of BMI has been empirically supported as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI = 18.5–24.99 kg/m2), and overweight (BMI = 25–29.99 kg/m2), obese I (BMI = 30–34.99 kg/m2), obese II (BMI = 35–39.99 kg/m2), and obese III (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) [21].

1.1 Participants

The cross-sectional non-probability sample was recruited from February–May 2020 and included a total of 1,034 responses. After data conditioning and excluding incomplete responses, the final sample included 733 participants. Participants were categorized as underweight (n = 52), normal weight (n = 364), overweight (n = 181), and obese I, II, and III (n = 136). BMI as a determinant of weight status was validated using one-tailed correlations with subjective figure rating scales: Female Body Scale (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), Female Fit Body Scale (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), Male Body Scale (r = 0.44, p < 0.001), and Male Fit Body Scale (r = 0.22, p = 0.039) [23, 24]. The men and women in our sample had similar BMI means of 25.08 and 25.86, respectively. Individuals who were overweight (M = 30.54) or obese (M = 30.90) were significantly older than those who were underweight (M = 24.69) or normal weight (M = 26.37).

1.2 Measures

1.2.1 Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire administered collected participants’ age (“What is your age in years?”), gender (“What is your gender?”), height (“What is your current estimated height?”), and weight (“What is your current estimated weight?”)

1.2.2 Eating pathology symptoms inventory

The Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI) was derived from the DSM-5 and is a reliable measure to assess disordered eating within the past month [25]. The EPSI includes eight subscales: Body Dissatisfaction (α = 0.87), Binge Eating (α = 0.88), Cognitive Restraint (α = 0.72), Purging (α = 0.89), Restricting (α = 0.86), Excessive Exercise (α = 0.86), Negative Attitudes Toward Obesity (α = 0.88), and Muscle Building (α = 0.79). The 45 items are answered with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

1.3 Procedure

This study was approved by the University of University of New Brunswick Saint John Research Ethics Board (REB File #056-2020). The participants were recruited from social media and SONA, an online participant recruitment tool. Social media participants responded to a post in which they were informed on the general purpose of this study, as well as administration details. All participants completed the questionnaires through Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). After providing informed consent, participants completed the questionnaire package. The demographic questions were presented first, followed by the randomized set of questionnaires. Debriefing information and the opportunity to enter a draw prize were presented after the completion of the questionnaire package.

2 Results

Prior to data analyses, a power analysis was conducted to ensure that the number of participants in each weight category was sufficient to conduct inferential analyses. Further, the assumptions underlying the statistical analyses were examined. To assess the research objective, correlations between BMI and disordered eating components measured by the EPSI were examined for men and women (see Table 1). In both men and women, BMI was positively associated with Body Dissatisfaction and Binge Eating. In men, having a higher BMI was correlated with Cognitive Restraint and Negative Attitudes Toward Obesity. In contrast, women with a lower BMI reported experiencing greater Restricting, Excessive Exercise, and Muscle Building. An r-to-z transformation was conducted to examine if the strength of the correlations were different for men and women. Overall, there were few gender differences; the correlations between BMI and Restricting and Excessive Exercise were stronger for women than for men.

Overall, among women, the inverse correlations indicated that Restricting, Excessive Exercise, and Negative Attitudes towards Obesity, and Muscle Building were associated with being younger (see Table 1). Interestingly, the correlations between age and Body Dissatisfaction, Cognitive Restraint, Purging, and Binge Eating were not statistically significant, suggesting that women of all ages reported similar levels of these aspects of DE. Interestingly, no statistically significant correlations between age and disordered eating variables were found among males. Overall, r-to-z transformations indicated that the inverse correlations between age and Restricting and Muscle Building were stronger for women than for men. As expected, BMI significantly increased with age in both men (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) and women (r = 0.19, p < 0.001).

A two-way MANOVA was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between gender and BMI categories across the disordered eating subscales. There was a statistically significant interaction effect between gender and BMI categories, as well as significant main effects of gender and BMI categories (see Table 2). The significant interaction, F(16, 1408) = 1.93, p = 0.014, Pillai’s Trace = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.02, indicated that the effect of BMI categories on the combined disordered eating scales differed for men and women. An examination of the univariate effects indicated a statistically significant interaction between gender and BMI on Body Dissatisfaction subscale. Post hoc comparisons, with Bonferroni corrections, indicated that underweight, normal weight, and overweight males had similar levels of body dissatisfaction; obese men reported higher Body Dissatisfaction (all ps < 0.01). Among females, underweight and normal weight individuals had lower Body Dissatisfaction than those who were overweight and obese (all ps < 0.01).

The multivariate main effect of BMI was statistically significant, F(24, 2109) = 4.78, p < 0.001, Pillai’s Trace = 0.16, ηp2 = 0.05. There were statistically significant differences in all components of disordered eating, except for Excessive Exercise, Purging, Negative Attitudes towards Obesity, and Muscle Building. Post hoc analyses indicated that individuals who were overweight and obese had significantly higher Body Dissatisfaction and Binge Eating than normal weight and underweight individuals (all ps < 0.001). On the Cognitive Restraint subscale, obese individuals had higher scores than the underweight (p = 0.022) and normal weight (p = 0.009) individuals; post hoc analyses indicated no additional statistically significant comparisons on this subscale. On the Restricting subscale, underweight individuals had higher scores than individuals in the other weight categories (all ps < 0.001); further, normal weight individuals reported higher Restricting than overweight individuals (p < 0.001). The multivariate main effect of gender was statistically significant, F(8, 701) = 19.58, p < 0.001, Pillai’s Trace = 0.18, ηp2 = 0.18. Regardless of BMI, men reported statistically higher levels of Purging (p = 0.036), Excessive Exercise (p = 0.002), Negative Attitudes towards Obesity (p < 0.001), and Muscle Building (p < 0.001) than women.

3 Discussion

The objective of this study was to expand upon AN attitudes and behaviours associated with underlying weight membership to support recent literature suggesting that attitudes and behaviours typically associated with AN are also reported by individuals with higher BMIs. In addition, we were interested in examining differences in components of DE as a function of age and gender. Comparative analyses were used on survey data collecting on the frequency and severity of disordered eating symptoms. The current findings revealed that lighter-weight individuals reported higher levels of AN-specific behaviour, restricting eating, compared to heavier-weight participants. In contrast, heavier-weight individuals had higher AN-related attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours, such as body dissatisfaction, cognitive restraint, and binge eating. The DSM-5 criteria for AN include a "disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced,” “intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat,” and, in the binge-eating/purging type, “recurrent episodes of binge-eating” [13, p. 382]. Importantly, although these results support that AN attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours can be found in individuals regardless of if underweight or obese, these disordered eating components are not exclusive to AN and can be found in other eating disorder requirements for diagnosis. Therefore, this study’s findings do not support using a categorical model to distinguish individuals with typical and atypical AN, and any eating disorder category.

Individuals with heavier BMIs are constantly preoccupied with concerns about their eating and weight/shape [26]. Considering that underweight participants reported the highest levels of restricting eating, the current findings support that heavier-weight individuals may be faced with conflicting variables that prevent maintaining restricting behaviours, thus, resulting in significant weight fluctuations [27]. Further, individuals who are obese reported higher levels of body dissatisfaction and bingeing than individuals in lower weight categories, further compounding their struggles with disordered eating.

Furthermore, gender is important to consider in disordered eating research [28]. Having a high BMI was related to experiencing greater body dissatisfaction and binge eating, regardless of gender. Significant associations between higher BMI and experiencing cognitive efforts to restrict eating and negative attitudes toward obese individuals were only found in the male sample. In contrast, women with lower BMI tended to engage in higher levels of restricting eating, excessive exercise, and muscle building. When directly comparing the two genders amongst each other, women with higher BMIs were significantly less likely to exercise excessively compared to men; men with lower BMIs tended to have greater negative perceptions toward individuals presenting with an overweight or obese weight status.

Gender and BMI category membership interact with one another to influence the frequency and severity of disordered eating. Underweight men and women have similarly low levels of body dissatisfaction; however, body dissatisfaction increases with BMI much more significantly in women compared to men. Specifically, the current results suggest that underweight, normal weight and overweight men have similar and lower levels of body dissatisfaction than obese men. Other researchers support that higher BMI in women is strongly associated with body dissatisfaction because the media and society strongly attend to physical appearance in women, as well as emphasize the relation between beauty and thinness [29]. Previous research [30] shows that young women are more vulnerable to these social and media pressures than older women, which is consistent with the present findings.

Taken together, similarities were found across the weight status spectrum, including comparable levels of disordered eating components that are generally associated with AN, such as purging, excessive exercise, and negative attitudes toward obesity. In addition, the differences found between the weight categories, such that individuals who are overweight or obese had higher body dissatisfaction cognitive restraint, support that AN is not a diagnosis exclusive to lighter-weight individuals. The findings from this study support the movement toward conceptualizing eating disorders in a dimensional way. Yet, the weight-based criteria (e.g. DSM-5) for diagnosing AN can harm these individuals by excluding them from evidence-based practices [11]. Despite having anorexic cognitions, attitudes, and behaviours, higher-weight individuals may be erroneously encouraged to lose weight as their treatment goal [20]. Attributing weight to be the problem instead of the disordered eating thoughts and behaviours can lead to weight cycling, which has harmful effects on a person’s health [20]. These results support that future research is needed to develop interventions addressing anorexic symptoms in people who are considered overweight or obese to meet their specific needs. Future research should also use clinical samples to explore differences between typical and atypical AN amongst the subtypes (restricting versus binge-eating/purging type).

3.1 Limitations

As is typical of survey research, the current data was collected using non-probability, cross-sectional sampling. Although this method allowed us to collect a large, diverse sample, the current results do not allow inferences about causality or generalization to the larger population of individuals with disordered eating behaviours, thoughts, or attitudes. Further, although self-reported weight can also be inaccurate which would also affect the validity of the BMI, many studies have reported on the accuracy of self-reported height and weight when compared to actual body measures in younger adults (18–24 years old) and older adults (30–75 years-old) [31, 32]. Moreover, despite the strong validity and reliability of the EPSI, the lack of cut-off scores prohibited the comparisons between clinical levels of eating pathology across weight categories, which would have further realized the purpose of this study. Lastly, our data was collected during the first year of the coronavirus pandemic (January–April 2021), which may have influenced the outcomes.

3.2 Conclusion

Atypical AN is a diagnosis introduced in the DSM-5 to address the strict weight criteria in typical AN, which resulted in the exclusion of heavier-weight individuals from beneficial interventions. Although weight is generally a reliable predictor of health outcomes, the findings support other literature indicating that it does not necessarily imply that overweight and obese individuals do not experience typical AN symptoms, even to a lesser degree. Future research should validate these findings using clinical samples of typical and atypical AN patients.

Data availability

Supporting data is available from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition

- DSM-IV-TR:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision

- EPSI:

-

Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of variance

References

Bilali A, Galanis P, Velonakis E, Katostaras T. Factors associated with abnormal eating attitudes among Greek adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42(5):292–8.

Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: Could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? Int J Eating Disord. 2003;34(S1):S117.

Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, Quirk F, Buttner P, Kennedy L. The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(2):104–8.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M. Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):244–51.

Heaven PCL, Mulligan K, Merrilees R, Woods T, Fairooz Y. Neuroticism and conscientiousness as predictors of emotional, external, and restrained eating behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(2):161–6.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2000.

Fisher M, Gonzalez M, Malizio J. Eating disorders in adolescents: how does the DSM-5 change the diagnosis? Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27(4):437–41.

Forney KJ, Brown TA, Holland-Carter LA, Kennedy GA, Keel PK. Defining “significant weight loss” in atypical anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(8):952–62.

Walsh BT, Hagan KE, Lockwood C. A systematic review comparing atypical anorexia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23856.

Silén Y, Raevuori A, Jüriloo E, Tainio VM, Marttunen M, Keski-Rahkonen A. Typical versus atypical anorexia nervosa among adolescents: clinical characteristics and implications for ICD-11. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(5):345–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2370.

Moskowitz L, Weiselberg E. Anorexia nervosa/atypical anorexia nervosa. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Car. 2017;47(4):70–84.

Levinson CA, Brosof LC, Ram SS, Pruitt A, Russell S, Lenze EJ. Obsessions are strongly related to eating disorder symptoms in anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2019;34:101298.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 (R)). 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013.

Whitelaw M, Lee KJ, Gilbertson H, Sawyer SM. Predictors of complications in anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa: degree of underweight or extent and recency of weight loss? J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):717–23.

Garber AK, Cheng J, Accurso EC, Adams SH, Buckelew SM, Kapphahn CJ, et al. Weight loss and illness severity in adolescents with atypical anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):e20192339.

Hooley JM, Butler JN, Nock M, Mineka S. Abnormal psychology. 17th ed. London: Pearson; 2017.

Strother E, Lemberg R, Stanford SC, Turberville D. Eating disorders in men: underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood. Eating Disord. 2012;20(5):346–55.

Murray SB, Griffiths S, Mond JM. Evolving eating disorder psychopathology: Conceptualising muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(5):414–5.

Wu XY, Yin WQ, Sun HW, Yang SX, Li XY, Liu HQ. The association between disordered eating and health-related quality of life among children and adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0222777.

Spotts-De Lazzer A, Muhlheim L. Could your higher weight patient have atypical anorexia? J Health Serv Psychol. 2019;45(1):3–10.

Weir CB, Jan A. BMI Classification percentile and cut off points. Florida: Treasure Island; 2021.

American Psychiatric Association. Section III. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-Section-III.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Ralph-Nearman C, Filik R. New body scales reveal body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal, and muscularity-ideal in males. AM J Mens Health. 2018;12(4):740–50.

Ralph-Nearman C, Filik R. Development and validation of new figural scales for female body dissatisfaction assessment on two dimensions: thin-ideal and muscularity-ideal. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(114):1.

Forbush KT, Wildes JE, Pollack LO, Dunbar D, Luo J, Patterson K, et al. Development and validation of the eating pathology symptoms inventory (EPSI). Psychol Assess. 2013;25(3):859–78.

Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, Rodgers B, Owen C. Disordered eating behaviours and cognitions in young women with obesity: relationship with psychological status. Int J Obes. 2007;31(5):876–82.

Witt AA, Berkowitz SA, Gillberg C, Lowe MR, Råstam M, Wentz E. Weight suppression and body mass index interact to predict long-term weight outcomes in adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(6):1207–11.

Beaulieu DA. From one end of the scale to the other: The relative influence of shared and distinct factors in disordered eating and weight status [thesis]. Saint John: University of New Brunswick; 2022.

Weinberger N-A, Kersting A, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck-Sikorski C. Body dissatisfaction in individuals with obesity compared to normal-weight individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Facts. 2016;9(6):424–41.

Rohde P, Stice E, Shaw H, Gau JM, Ohls OC. Age effects in eating disorder baseline risk factors and prevention intervention effects. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(11):1273–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22775.

Nyholm M, Gullberg B, Merlo J, Lundqvist-Persson C, Råstam L, Lindblad U. The validity of obesity based on self-reported weight and height: implications for population studies. Obesity. 2007;15(1):197–208.

Quick V, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Shoff S, White AA, Lohse B, Horacek T, et al. Concordance of self-report and measured height and weight of college students. J Nutr Educ and Behav. 2015;47(1):94–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Lilly Both and Dr. Bryn Robinson for serving on Danie Beaulieu’s graduate supervisory committee. Dr. Janine Olthuis provided invaluable comments that informed the presentation of the current results.

Funding

The first author was supported by a University of New Brunswick Graduate Studentship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The data in this paper were collected as part of DB’s masters thesis. LB is her primary graduate supervisor. DB and LB contributed to the development of the project and the current data analytic plan. DB wrote the initial draft and conducted the data analysis. LB edited drafts of the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was reviewed by the University of New Brunswick Research Ethics Board (File number: #056-2020).

Consent for publication

We have both reviewed the final manuscript and consent to publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beaulieu, D.A., Best, L.A. From one end of the scale to the other: overweight and obese individuals’ experiences with anorexic attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours. Discov Psychol 3, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-023-00079-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-023-00079-1