Abstract

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation drives the net production of tropospheric ozone (O3) and a large fraction of particulate matter (PM) including sulfate, nitrate, and secondary organic aerosols. Ground-level O3 and PM are detrimental to human health, leading to several million premature deaths per year globally, and have adverse effects on plants and the yields of crops. The Montreal Protocol has prevented large increases in UV radiation that would have had major impacts on air quality. Future scenarios in which stratospheric O3 returns to 1980 values or even exceeds them (the so-called super-recovery) will tend to ameliorate urban ground-level O3 slightly but worsen it in rural areas. Furthermore, recovery of stratospheric O3 is expected to increase the amount of O3 transported into the troposphere by meteorological processes that are sensitive to climate change. UV radiation also generates hydroxyl radicals (OH) that control the amounts of many environmentally important chemicals in the atmosphere including some greenhouse gases, e.g., methane (CH4), and some short-lived ozone-depleting substances (ODSs). Recent modeling studies have shown that the increases in UV radiation associated with the depletion of stratospheric ozone over 1980–2020 have contributed a small increase (~ 3%) to the globally averaged concentrations of OH. Replacements for ODSs include chemicals that react with OH radicals, hence preventing the transport of these chemicals to the stratosphere. Some of these chemicals, e.g., hydrofluorocarbons that are currently being phased out, and hydrofluoroolefins now used increasingly, decompose into products whose fate in the environment warrants further investigation. One such product, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), has no obvious pathway of degradation and might accumulate in some water bodies, but is unlikely to cause adverse effects out to 2100.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The protection of stratospheric ozone (O3) has had important consequences for the chemical composition of the lower atmosphere (the troposphere) and the quality of the air that humans and many other organisms breathe. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation plays an essential role in the generation of photochemical smog, exposure to which is associated with widespread health effects, reductions in life expectancies, damage to forests, and smaller agricultural yields. Given the number of populations and ecosystems currently affected by photochemical smog, even small changes in UV radiation are important, such as those associated with the few percent depletion of stratospheric O3 that occurred at mid-latitudes over 1980–2000. By limiting the depletion of stratospheric O3, the Montreal Protocol has avoided large increases in tropospheric UV radiation that would have exacerbated photochemical air pollution in urban areas.

On the global scale, UV-B radiation (280–315 nm) controls the self-cleaning capacity of the troposphere by generating hydroxyl radicals (OH). These radicals react with many chemicals emitted to the troposphere, including greenhouse gases such as methane, facilitating their removal from the atmosphere and essentially determining their atmospheric lifetime. The Montreal Protocol has maintained the troposphere’s self-cleaning capacity at near natural levels, but future changes remain a concern, especially if the intensity of UV-B radiation decreases substantially due to increasing stratospheric ozone under some future scenarios.

Actions under the Montreal Protocol have led to the introduction of new chemicals to the atmosphere as replacements to some of the ozone-depleting substances, including hydrofluorochlorocarbons (HCFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), hydrofluoroethers (HFEs), hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) and hydrochlorofluoroolefins (HCFOs). However, their atmospheric photo-degradation can lead to persistent secondary pollutants such as trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), whose ultimate fate in the environment remains unclear, requiring continued monitoring and assessment relative to other natural and/or anthropogenic sources.

We have reported on these issues in our previous assessments [1,2,3,4,5,6] and our objective here is to provide an updated overview and assessment of the scientific evidence. As will be presented in the following sections, our previous conclusions remain qualitatively unchanged and consistent with increasingly available observations and numerical simulations. This assessment consists of two parts: The first part (Sect. 2) focuses on the effects of depletion of stratospheric ozone, solar UV radiation (particularly UV-B), and interactions with climate change on tropospheric air quality and how changes in tropospheric air quality affect human health and ecosystems. The second part (Sect. 3) assesses the known sources of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), including those related to the replacement chemicals under the purview of the Montreal Protocol, and their potential risk to humans and ecosystems.

In conducting this assessment, we have searched the literature through PubMed®, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect®, and relevant journals to obtain peer-reviewed papers from the recent literature (2018–2022) as well as reports from recognized international agencies (e.g., World Health Organization) and government agencies (e.g., US Environmental Protection Agency). We have critically evaluated these papers and reports before including information from them in this Quadrennial Assessment.

2 UV-dependent air pollutants and their effects on human health, plants, and the self-cleaning capacity of the troposphere

The importance of UV radiation to the formation of some types of air pollution has been known at least since the studies of photochemical smog in Los Angeles in the 1950s, when it was shown that ambient O3 was generated by UV-induced reactions involving nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [7]. Since then, many details of these photochemical reactions have been elucidated, such as the central role of UV-generated OH radicals in controlling the overall reactivity; and the formation of O3, peroxides, acids, and other harmful gaseous intermediates, including some that can condense to form particulate matter (PM). This gas- and condensed-phase chemistry is complex, involving hundreds of different chemicals, often with rapidly changing emissions and different environmental conditions.

A brief overview/summary of tropospheric chemistry, with emphasis on the distinct roles of UV-B and UV-A radiation, is provided in Sect. 2.1. The formation of photochemical smog, specifically its ground-level O3 and UV-sensitive PM components, is discussed in Sects. 2.2 and 2.3, including an assessment of the possible effects of changes in UV radiation related to the recovery of stratospheric ozone over the coming decades. Exposure to photochemical smog can have large impacts on human health, particularly in vulnerable populations even at low concentrations of pollutants (Sect. 2.4). Tropospheric O3 and PM can also affect plant health (Sect. 2.5). UV-B radiation has beneficial effects by causing the formation of OH, the cleaning agent of the troposphere (Sect. 2.6). Finally, changes in atmospheric circulation and the transport of pollutants affect the tropospheric air quality (Sect. 2.7). A summary of our assessment is provided in Sect. 2.8.

2.1 Background: the UV photochemistry of tropospheric air

The most important UV-induced processes that control air quality in the troposphere are shown in Fig. 1. UV-B radiation is responsible for the formation of the OH radical, the major oxidizing agent in the troposphere. This occurs through the photolysis of O3 and subsequent reaction of an electronically excited oxygen atom with water (H2O). Hydroxyl radicals are lost by reaction with reduced chemicals, including carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), VOCs, sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) (Fig. 1). Hydroxyl radicals control the atmospheric amounts of these chemicals as well as those of many other important trace gases, e.g., HFCs, HCFCs, HFOs, and very-short-lived substances (VSLSs, e.g., halo-organics with a lifetime of less than or equal to 6 months). Chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that do not react with OH have the potential to reach the stratosphere in large amounts; the CFCs were, therefore, replaced with chemicals that react with OH (HCFCs, HFCs, HFOs, etc.).

Simplified schematic of tropospheric photochemistry. UV-C radiation (100–280 nm) in the stratosphere generates ozone, O3, some of which is transported to the troposphere. UV-B radiation initiates tropospheric chemistry by photo-dissociating O3 and generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH). These react with many compounds emitted by human activities and natural processes, e.g., carbon monoxide, methane, volatile organic compounds including halocarbons, and others, all generalized in the figure as RC (reduced compounds). By removing these compounds, the concentration of OH controls the self-cleaning capacity of the atmosphere. Nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) catalyze the photo-oxidation by regenerating OH via reaction of NO with HO2. This coupling of the NOx and HOx (OH + HO2) cycles also leads to autocatalytic production of O3, often in amounts larger than lost initially via its UV-B photolysis, since NOx and HOx molecules can cycle many times before being removed. The cycles are terminated by reaction with OH to make nitric acid, (HNO3) or by reaction of HO2 to inorganic or organic peroxides, e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Other products, depending on the reduced compounds being oxidized by OH, could include partly oxidized organics, secondary organic aerosols (SOA), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

UV-B and UV-A radiation are together responsible for the net production of O3 in the troposphere. This occurs via photo-dissociation of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) to NO and O, mainly by UV-A radiation, and subsequent reaction of the oxygen atom with molecular oxygen (Fig. 1). Nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) are emitted primarily as NO, and the NO2 is produced via the re-cycling of the hydroxyl radical (OH) generated from the UV-B photolysis of O3. Due to this autocatalytic production of O3 involving OH, the net production of O3 depends not only on UV-A radiation but also on UV-B radiation. The different effects of UV-B and UV-A radiation are discussed in more detail in Box 1. Note that Fig. 1 is restricted to reactions occurring in the gas phase, while heterogeneous, UV-induced processes involving aerosols are discussed in Sect. 2.3.

2.2 UV radiation and ground-level ozone

Ground-level O3 continues to be a major environmental problem, with costly impacts on human health and vegetation. Most ground-level O3 is produced by the UV photochemical processing of pollutants (see Sect. 2.1), with occasional contributions from downward transport of ozone-rich stratospheric air (see Sect. 2.7). It is generally accepted that concentrations of O3 have increased throughout the global troposphere over the past century, due to increasing emissions of VOCs and NOx. This is borne out in numerical simulations with chemistry-climate models, as shown in Fig. 2. Contributions from stratospheric ozone depletion (1980 to current) and the associated increases in UV-B radiation have been negligible by comparison, at least for the global scale. Future projections tend to show an increasing global burden of tropospheric O3, although the details depend on the assumed scenario of greenhouse gas emissions (only one shown in the figure, SSP370).

Global tropospheric ozone (Tg) estimated by multi-model assessments (MMM, ACCMIP, TOAR) and observations (OBS, for the year 2000). Future projections are for one Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP370 scenario). From IPCC 2021 Ch. 6 [11]

Trends in local and regional concentrations of tropospheric O3 vary greatly as shown in Fig. 3. Over the past few decades, concentrations of O3 at ground-level and in the lower atmosphere have been generally decreasing in most developed countries, while increasing greatly in some locations including East and South Asia, in response to changes in emissions of NOx and VOCs. Reductions in emissions of NOx and VOCs will be necessary to reverse the observed increasing trends, but any substantial future changes in UV radiation could modify the effectiveness of such reductions.

Regional and local trends in tropospheric ozone at the surface and lower atmosphere. From IPCC 2021 Ch. 6 [11]

The possibility that ground-level O3 can be affected by changes in UV related to depletion of stratospheric ozone was first pointed out by Liu and Trainer [12] and has since been confirmed by several studies using numerical models [13,14,15,16,17], as well as observations at the South Pole [18] and at mid-latitudes [19]. More intense UV-B irradiation generally induces faster chemical reactivity in air parcels (Box 1), leading to faster removal of primary chemicals, but also more rapid and intense build up (and removal) of intermediate or secondary pollutants, such as hetero-organics (e.g., aldehydes, ketones, and organic nitrates) and other by-products including O3, peroxides, and secondary PM. Conversely, reductions in UV radiation decrease chemical reactivity, causing slower production of O3 and other photochemical pollutants near source regions, e.g., urban areas, while slowing the destruction on regional and global scales.

The decreases in UV radiation at the surface, expected from the recovery of stratospheric O3, to 1980 levels are estimated to have only a small impact on ambient O3, as reported previously [14, 15], since reductions of O3 at mid-latitudes have been limited to only a few percent (relative to a 1980 baseline). For the United States, the recovery to 1980 levels will increase the O3 column by 4–6%, and the resulting lower levels of UV radiation will tend to lower ambient O3 over a few large urban areas, while raising it slightly elsewhere, consistent with an overall slower chemical reactivity. However, recent climate model simulations [20,21,22], also reviewed by Bernhard et al. [23], suggest that under some scenarios of increasing greenhouse gas emissions, stratospheric O3 could exceed the 1980 baseline (the so-called “super-recovery”). By 2100, stratospheric O3 could increase by an additional 10% (above the 1980 levels) under high emission scenarios (SSP3-7.0, SSP4-6.0 and SSP5-8.5; see Fig. 3 of Bernhard et al. [23]). This would decrease tropospheric JO3 by about 14% (Box 2), like the changes used in the sensitivity calculation shown in Box 3. Under these scenarios, the changes in tropospheric O3 (urban declines and regional increases) would be about three times greater than those estimated for recovery limited to 1980 levels [14, 15]. Even at current levels (see Figs. 2 and 3), ground-level O3 damages vegetation and causes economically significant reductions in crop yields (see Sects. 2.4 and 2.5). Additional increases due to the recovery (or super-recovery) of stratospheric O3 are of concern but could be offset by more stringent reductions in emissions of NOx and VOCs.

Much larger changes would have occurred without the implementation of the Montreal Protocol (the “world avoided”), where unabated growth of emissions of CFCs would have resulted in catastrophic global loss of stratospheric O3 [24], with major impacts on UV radiation [25], incidence of skin cancer [26, 27], and reduction of the global carbon sink by damage to vegetation [28]. However, to our knowledge, calculations of the impacts of such large increases in UV radiation on air quality, particularly ambient O3 and secondary aerosols, have not been carried out.

While large changes in UV-B radiation have been avoided by the Montreal Protocol [23], trends and variability in UV radiation exist also for other reasons (especially due to aerosols and clouds), and these changes provide ongoing opportunities to better understand and quantify the representation of UV-driven chemical processes in models for air quality. Reduced emissions have systematically improved air quality in many locations, but this has increased UV radiation near the surface, potentially negating some of the benefits of the reduced emissions. For example, aerosol haze in China was reduced substantially during the last decade due to lower emissions of NOx and SO2. This has led to surface brightening (e.g., by 0.70–1.16 W m−2 year−1 in eastern China over 2014–2019) [29] but also to undesirable increases in ambient O3 [30,31,32,33] (e.g., by 2–6 µg m−3 year−1 in megacity clusters of Beijing and Shanghai over 2013–2017) [34]. Simulations with numerical models show several possible reasons including increases in UV radiation [31, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39], shifts in the VOC/NOx chemical regime resulting in increased production of O3 efficiency [35, 40], higher emissions of biogenic VOC due to rising temperatures [30], and decreased competition for gas-phase radicals by aerosol surfaces [34, 40], with reality likely being a combination of these factors.

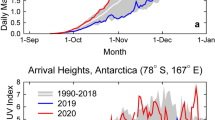

Long-term increases in UV radiation at the surface due to improved local air quality have been recorded in many other locations. For example, increasing trends in UV radiation over 1996–2016 were found [41] for stations in Japan and Greece, and were attributed to reductions in absorbing aerosols. More recently, Ipiña et al. [42] found that the UV Index in Mexico City increased by ca. 20% over 2000–2019 (due to reductions in PM, SO2, O3, and NO2) and estimated that such increases in UV radiation would require an additional 10% reduction in VOC emissions to meet the same ground-level O3 concentrations had the UV remained constant. Brief increases in UV radiation at the surface have been observed during the economic slowdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g., in Brazil [43], East Asia [44], India [45], and likely in many other locations. Analysis of these data is ongoing and should yield insights on how atmospheric pollution responds to changes in UV radiation under different conditions.

2.3 UV radiation and particulate matter

Particulate matter is a major component of air pollution, and particles smaller than about 2.5 µm (PM2.5) are believed to be particularly damaging due to their ability to penetrate deeply into lungs. A large fraction of PM2.5 is formed by UV-initiated photochemistry. While “primary” PM is emitted directly (e.g., dust, black carbon, or sea spray) “secondary” PM is produced in the atmosphere, typically by condensation of gases having low saturation vapor pressures. These condensable gases are mostly produced by reactions of OH with pollutants such as SO2, NO2, or VOCs, to yield sulfate, nitrate, or secondary organic aerosols (SOA), respectively:

where the last two reactions involve several intermediate steps. The rate-limiting step in the production of these particles is the reaction of OH with the precursors (NO2, SO2, or VOCs), so that the dependence of OH on UV radiation (see Sect. 2.1) applies directly to the rate of formation of secondary PM as well. Decreases (increases) in stratospheric O3 lead to increases (decreases) in tropospheric UV-B radiation and concentrations of OH radicals, and therefore to faster (slower) formation of these PM. The Montreal Protocol, through its influence on the amount of UV radiation reaching the troposphere, has direct consequences for the formation of secondary PM. Primary PM, on the other hand, is not expected to depend strongly on UV irradiation.

The relative amounts of primary and secondary PM vary greatly in time and space, and estimates exist only for regions where reliable emission inventories exist. For the contiguous United States (Fig. 4) modeling studies indicate that more than half of the PM2.5 is secondary in origin, and thus directly sensitive to variations in UV radiation [46]. Globally, major contributors to PM2.5 are sulfate, nitrate, organics, ammonium, and black carbon (see Fig. 6.7 of IPCC 2021 [11]). While sulfate and nitrate PM are of secondary origin, for organics the relative global contribution of primary and secondary PM is less clear. Satellite-based observations of aerosol optical properties provide only very limited information about chemical composition [47, 48]. A better understanding of the secondary/primary ratio of PM2.5 in all populated regions is required to fully assess the role of UV radiation and, hence, the relevance of the Montreal Protocol to this global air pollution problem.

Composition of PM2.5 over the contiguous United States calculated with a chemistry-transport model. Particles produced by UV photochemical reactions (secondary aerosols) include sulfate (SO4), ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) and secondary organic aerosols (SOA) from anthropogenic or biogenic precursors (SOAAVOC and SOABVOC, respectively), and account for more than half of the total PM2.5, compared to directly emitted particles (primary aerosols) such as dust, soot, and sea spray. VOC, volatile organic compounds. From Pye et al. [46]

An emerging and rapidly evolving topic is the effect of UV radiation on chemical reactions within and on the surface of aerosol particles. These heterogeneous processes are extremely complex and still poorly understood, at least in part because aerosols may be composed of many different chemicals, often mixed within the same particle, and each with different UV-absorbing properties and different photolytic fragments. Depending on the specific particle, several UV-mediated processes have already been identified: (a) photolysis of particle-bound organic chemicals into volatile gases (e.g., CO and CO2), leading to loss of particle mass [49,50,51,52,53,54]; (b) photolysis of particle-bound inorganic and organic nitrogen into gaseous NO, NO2, or HONO, potentially increasing the oxidizing capacity of the atmosphere [55,56,57,58]; (c) conversion of SO2 gas on the surface of particles to particulate sulfate (thus, increasing the mass of the particle) [59,60,61]; (d) formation of molecular chlorine (Cl2) leading to enhanced reactivity of a daytime suburban atmosphere [62], (e) increased absorption of shortwave radiation (from formation of brown carbon) with consequences for radiative forcing of climate [63,64,65,66,67]; and (f) formation of various reactive oxygen species (ROS), some of which (e.g., peroxides) are sufficiently long-lived that they may persist during inhalation and play a major role in deleterious health effects of air pollution [61, 64, 68,69,70,71,72].

Ultraviolet-induced photo-processes within and on the surface of aerosols can also increase the ability of aerosols to act as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) [73, 74], which can change cloud properties and therefore indirectly impact climate. UV-B irradiation (~ 4.5 days solar radiation equivalent) of dissolved organic matter (DOM, used as a surrogate for organic aerosols) from freshwaters resulted in an increase of hygroscopicity by up to 2.5 times [73]. This is a result of the photo-degradation of DOM into hydrophilic low molecular weight chemicals, a process that has been reported in sunlit surface waters [75, 76]. A similar effect on CCN was also observed upon UV-B irradiation of SOA formed from the oxidation of α-pinene and naphthalene [74], which are biogenic and anthropogenic SOA precursors, respectively. Considering that CCN are central to the lifecycle of clouds, this represents a newly recognized and potentially important dependence of the hydrological cycle (and climate in general) on UV radiation.

In most cases, the spectral dependence of these heterogeneous photo-processes is still unknown, so that it is not yet possible to assess reliably how much they would be influenced by changes in UV-B radiation resulting from changes in stratospheric ozone. As more spectral data become available, our understanding of the multiple ways in which UV radiation influences aerosol properties and lifetimes will increase and illuminate what role this plays in the natural and perturbed atmosphere.

In summary, changes in UV radiation affect the formation, transformation, and destruction of PM. Quantification of these effects of UV radiation is still somewhat problematic because it involves complex chemical feedbacks that depend on specific physical and chemical variables, such as temperature, humidity, and the amounts of VOCs and NOx present. However, despite this uncertainty, even small changes in UV radiation should be of concern, because of the large number of people currently exposed to poor air quality and its significance to human health.

2.4 Health impacts of photochemical smog

Air pollution is a major public health concern. Estimates of the impacts vary but are consistently large. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 4.2 million deaths every year occur because of exposure to ambient (outdoor) air pollution which includes particulates and gases, such as O3, NOx, etc. [77]. These values are somewhat higher than the values reviewed in our previous assessment, which ranged from 1.75 to 4.3 million depending on year and source of estimates [6]. Regular reports on concentrations of tropospheric O3 and its effects on humans and the environment are published in Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Reports, e.g., [78]. Our previous Quadrennial Assessment [6] provided an overview of the effects of air pollution on human health with much of the information focusing on respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, although reproductive and neurological effects were also briefly addressed. Information on these and other effects from exposure to air pollution continues to accumulate.

An umbrella review (a review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [79] evaluated 548 meta-analyses derived from 75 systematic reviews on non-region-specific associations between outdoor air pollution and human health. Of these meta-analyses, 57% (313) were not statistically significant. Of the 235 nominally significant meta-analyses, all but 5 indicated an adverse effect on human health. Analyses were graded as strong (13), highly suggestive (23), suggestive (67) or weak (132). Strong evidence for an association between outdoor air pollution exposure and cardiorespiratory diseases was found for:

-

(1)

an increased risk of stroke-related mortality per 10 µg m−3 increase of PM10 and PM2.5 (short-term exposure; relative risk (RR): 1.005 95% CI 1.003–1.007 and RR: 1.014, 95% CI 1.009–1.020, respectively);

-

(2)

hypertension per 10 µg m−3 increase of PM2.5 (short-term exposure; odds ratio (OR) 1.097, 95% CI 1.060–1.136);

-

(3)

asthma-related admissions per 10 µg m−3 increase of PM2.5 and NO2 levels (short-term exposure; OR: 1.022, 95% CI 1.014–1.031 and OR: 1.019, 95% CI 1.1013–1.024, respectively);

-

(4)

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma-related admissions of the elderly per 10 µg m−3 increase of NO2 (24 h average; RR: 1.386%, 95% CI 1.110–1.661%);

-

(5)

mortality due to pneumonia per 10 µg m−3 increase NO2 levels (long-term exposure; Hazard Ratio (HR): 1.077, 95% CI 1.060–1.094).

2.4.1 Health impacts at low concentrations of air pollution

New studies, assessed here, indicate that even relatively low levels of pollution may be detrimental [80,81,82]. Many countries have acted by regulating concentrations of key pollutants and there has been a remarkable decrease in air pollution levels in almost all countries with developed economies leading to levels below the air pollution standards. With the decrease in concentrations of key pollutants, studies now show the detrimental effects on health at relatively low levels of air pollution. Many show effects at concentrations lower than the current annual average standard. In response to this, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its 2005 Global Air Quality Guidelines (AQG) in September 2021 [83, 84]. These new air quality guidelines [83] set ambitious goals, which will be difficult to achieve in most countries. They reflect the large impact that air pollution has on health globally. The new guidelines are aiming for annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 not exceeding 5 µg m−3 and NO2 not exceeding 10 µg m−3, and the peak season mean 8-h O3 concentration not exceeding 60 µg m−3 [83]. For comparison, the corresponding 2005 WHO guideline values for PM2.5 and NO2 were 10 µg m−3 and 40 µg m−3 with no recommendation issued for long-term concentrations of O3 [85]. Table 1 presents the new WHO guidelines in comparison to standards from the European Union, the EPA (USA) and China. Note that UV radiation is involved in the formation of many of these pollutants, including O3, NO2, and a large fraction of PM10 and PM2.5, including sulfate, nitrate, and secondary organic aerosols. Furthermore, UV radiation may make PM10 and PM2.5 more toxic by generating ROS (Sect. 2.3).

Evidence continues to accumulate demonstrating that exposure to air pollution can have serious effects on nearly all organ systems of the human body. As outlined in our earlier assessment, the health effects of air pollution include cardiovascular and respiratory disease, cancer, effects on the brain and the reproductive system including adverse birth outcomes [6]. Much of the more recent support documenting the effects of low-level exposure has come from the study of large cohorts in Canada [80], Europe [81] and the United States [82], where regulatory efforts have reduced the average level of exposure. These studies have consistently shown that the adverse effects of air pollution are not limited to high exposures; harmful health effects can be observed at very low concentrations (see below), with no observable thresholds below which exposure can be considered safe.

Research conducted as part of the ‘Effects of Low-Level Air Pollution: A Study in Europe’ (ELAPSE) [81, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92] examined the mortality and morbidity effects of exposure to low concentrations of four air pollutants: PM2.5, NO2, black carbon (BC), and tropospheric warm season O3, with some of the research also investigating the importance of elemental components of PM2.5 [88, 92,93,94]. The ELAPSE study consisted of two sets of cohorts: The first was a pooled cohort of up to 15 conventional research cohorts, most of which were in a region with at least one large city with an associated smaller town. This resulted in a rich amount of individual data for up to 325,000 participants. The second set of cohorts comprised seven large administrative cohorts, which were formed by linking census data, population registries, and death registries. These were analyzed individually, and, in some cases, meta-analyses were conducted to produce overall results. The key strength of the administrative cohorts was their large sample size (about 28 million) and national representativeness.

The effect of low-level air pollution exposure in 22 cohorts (a combination of research and administrative cohorts) across Europe was associated with several health outcomes and mortality [81]. Almost all participants had annual average exposures below the European Union guidance values (Table 1) for PM2.5 and NO2, and about 14% had mean annual exposures below the United States National Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM2.5 (12 µg m−3). In the pooled analysis of the research cohorts, participants had been exposed to 15 µg m−3 PM2.5, 1.5 × 10–5 m−1 black carbon (BC), 25 µg m−3 NO2, and 67 µg m−3 O3 on average. Among the cohorts, mean concentrations of PM2.5 ranged from 12 to 19 µg m−3, except for the Norwegian cohort (8 µg m−3). The study followed 325,367 adults and found significant positive associations between even low exposure to PM2.5, BC, and NO2 and mortality from natural-causes as well as cause-specific mortality such as cardiovascular and ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, COPD, diabetes, cardiometabolic disease, and lung cancer mortality [91]. An increase of 5 µg m−3 in PM2.5 was associated with 13% (95% CI 10.6–15.5%) increase in natural deaths. For participants with exposures below the United States standard of 12 µg m−3, an increase of 5 µg m−3 PM2.5 was associated with nearly a 30% [29.6% (95% CI 14–47.4%)] increase in natural deaths. For NO2, hazard ratios remained elevated and significant when analyses were restricted to observations below 20 μg m−3.

Liu and colleagues [95] analyzed the association between the incidence of asthma and low concentrations of air pollution using three large cohorts from Scandinavia (n = 98,326). They found a hazard ratio of 1.22 (95% CI 1.04–1.43) per 5 µg m−3 increase in PM2.5, 1.17 (95% CI 1.10–1.25) per 10 µg m−3 for NO2 and 1.15 (95% CI 1.08–1.23) per 0.5 × 10–5 m−1 for BC. Hazard ratios were larger in cohort subsets with exposure levels below the annual average limits for the European Union and United States (Table 1) and proposed World Health Organization guidelines for PM2.5 and NO2 (Table 1) compared to the hazard ratios in cohorts exposed to levels above the annual limits.

A meta-analysis [96] of 107 studies on the effect of long-term exposure to air pollution on mortality showed that there was strong evidence that exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 is associated with increased mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and lung cancer. The combined Hazard Ratios (HRs) for natural-cause mortality were 1.08 (95% CI 1.06, 1.09) per 10 µg m−3 increase in PM2.5, and 1.04 (95% CI 1.03, 1.06) per 10 µg m−3 increase in PM10. This study also indicated that associations with PM2.5 remained relevant below the current WHO standards of 10 µg PM2.5 m−3.

2.4.2 Health impacts due to components of particulate matter

Studies are only beginning to link health effects to specific chemicals identified in aerosols. Current guidelines and standards for PM are based on the mass of PM2.5, without consideration of chemical composition of the particles. Although it stands to reason that the chemical composition would be an important determinant of health impacts, relatively few studies have examined this specific issue. In the context of the Montreal Protocol, UV-dependent secondary PM (sulfate, nitrate, and secondary organics) is chemically distinct from primary, UV-independent, PM. Thus, the relative health impacts of secondary vs. primary PM are central to this assessment.

Several groups have examined exposure to elemental constituents of aerosols, e.g., Cu, Fe, K, Ni, S, Si, V and Zn in PM2.5 [92, 93, 97]. While most show increases in HRs with increasing atomic abundances, they cannot identify the contribution of secondary particulates, such as secondary organics, sulfates, and nitrates, that depend on UV radiation.

The composition of PM across the United States was modeled recently by Pye et al. [46], using the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model with improved representation of aerosol composition, and was analyzed for associations with mortality data (for 2016) for cardiovascular and respiratory disease. The median county-level cardiovascular and respiratory disease age-adjusted death rate was 320 per 100,000 population across 2708 counties, while the average concentration of PM2.5 was 6.5 μg m−3, with organic aerosols (OA) being the most abundant component at 2.9 μg m−3. They estimated that, across the United States, for every 1 μg m−3 increase in PM2.5, 'there is an increase of 1.4 (95% CI 0.5–2.3) cardiovascular and respiratory deaths per 100,000 people. The sensitivity appears much greater for OA, with increases of 1 μg m−3 leading to an increase of 8.1 (95% CI 5.4–11) cardiovascular and respiratory deaths per 100,000 people. Subdivision of OA into primary and secondary types showed greater sensitivity for the latter, especially for PM formed by the OH-initiated oxidation of natural VOCs, such as isoprene and terpenes, commonly emitted by vegetation. The importance of secondary organic PM is consistent with a likely role of ROS in tissue damage (Sect. 2.3).

In conclusion, early indications are that secondary aerosols, including SOA, may be particularly damaging. This is of direct relevance to the Montreal Protocol, since secondary aerosols are generated by UV-driven photochemistry. In many locations (e.g., the contiguous United States, see Fig. 4), secondary aerosols may be the largest and the most detrimental fraction of PM2.5.

2.4.3 Interactions of air pollution and temperature on health

Episodes of air pollution frequently occur in combination with extremes in temperature with synergistic effects on health depending on the pollutant(s) involved, the degree and direction of temperature change, and the characteristics of the geographic area and the populations affected. Reviews and meta-analyses of the adverse health effects from extremes of temperature (both highs and lows) have proliferated in recent years indicating just how much research in this area is being done due to concerns about climate change [98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106].

A study from nine European cities by Analitis et al. [107] reported that the daily number of deaths increases by 2.20% (95% CI 1.28–3.13) on days with high O3 per 1 °C increase in temperature. The interaction of temperature with PM10 was significant for cardiovascular causes of death for all ages (2.24% on days with low PM10 (95% CI 1.01–3.47), while it was 2.63% (95% CI 1.57–3.71) on days with high PM10.

In a recent meta-analysis, Areal et al. [108] showed that effects of air pollutants were modified by high temperatures, leading to higher mortality from respiratory diseases and an increase in hospital admissions. The effect of PM10 during higher temperatures increased the risk of mortality by 2.1%, and for hospital admissions the effects increased by 11%. The effects of ground-level O3 during high temperatures were similar [108].

2.4.4 Health impacts of air pollution in vulnerable populations

Air pollution affects people from the beginning to the end of life, causing a wide range of acute and chronic diseases. Sensitive populations include, among others, children, the elderly, and people with existing chronic diseases. Accordingly, people with cardiovascular diseases are more likely to suffer a heart attack, stroke, or death when exposed to air pollution [109].

Ambient air pollution not only contributes to adverse health outcomes in individuals after birth, but it may also have immediate adverse impacts on reproductive processes. Animal and epidemiological evidence demonstrates that air pollution may influence fertility. A large Danish study investigated 10,183 participants between 2007 and 2018 [110] who were trying to conceive. The study showed that higher concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 were associated with small reductions in fecundability, for example, the reductions in fecundability ratios from a one interquartile range (IQR) increase in PM2.5 (IQR = 3.2 µg m−3) and PM10 (IQR = 5.3 µg m−3) during each menstrual cycle were 0.93 (95% CI 0.87–0.99) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.84–0.99).

In another study on exposure to air pollution and the risk of pre-term birth, the authors investigated 2.7 million births across the state of California from 2011 to 2017 [111]. This study found an increased risk of pre-term birth with higher concentrations of PM2.5 [adjusted relative risks (aRR) (per interquartile increase)] = 1.04, (95% CI 1.04–1.05) and particulate matter from diesel exhaust, aRR = 1.02 (95% CI 1.01–1.03). Similar results were observed in another study from California, where the authors investigated 196,970 singleton pregnancies between 2007 and 2015. These authors found that, during cold seasons, increased exposure to PM2.5 during the three days prior to the premature birth was associated with 5–6% increased odds of very-early pre-term birth (ORlag3 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.11). These studies confirm results from human and other animal studies that air pollutants can enter a pregnant female’s circulatory system and exert many deleterious health effects in multiple body organs including the placenta and the developing fetus [111].

In the umbrella review discussed above, Markozannes et al. [79] also found strong associations for a number of pregnancy/birth related outcomes. These included:

-

(1)

a 10 µg m−3 increase in PM2.5 for various durations of exposure was associated with an increased risk of having an infant born small for gestational age, (a) long-term exposure entire pregnancy OR: 1.151, 95% CI 1.104–1.200; (b) long-term exposure first trimester: OR: 1.074, 95% CI 1.046–1.103; (c) long-term exposure last trimester: OR: 1.062, 95% CI 1.042–1.083;

-

(2)

a 13 µg m−3 increase in SO2, (24 h average) was associated with an increased risk of low birthweight OR: 1.035, 95% CI 1.031–1.049, as was

-

(3)

a 10 µg m−3 increase in PM10 (long-term exposure; mean difference 7.42 g, 95% CI 8.10–6.75;

-

(4)

a 10-µg m−3 increase in PM2.5 for the third trimester was associated with an increased risk for hypertension during pregnancy OR: 2.177 95% 1.710–2.773.

There is also growing evidence that exposure to air pollutants maybe detrimental to the central nervous system and contribute to deficits in cognitive development, neurodegenerative diseases and dementia [112, 113]. A recent review [113] found that, despite a substantial increase in publications, there is only suggestive evidence that air pollution may influence late-life cognitive health as there is still substantial heterogeneity of findings across the studies. The strongest effect found was with respect to PM2.5 and cognitive decline. The review included two different outcomes, namely, incidence of dementia and abnormal neuroimaging. Since then, a large Canadian study investigated the effect of exposure to air pollution and incidence of dementia in ~ 2.1 million individuals [114]. The study identified 257,816 incident cases of dementia and found a positive association between an interquartile range (IQR) increase in PM2.5 of 4.8 µg m−3 and incidence of dementia, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.04 (95% CI 1.03–1.05) and an IQR increase of 26.7 μg m−3 in NO2 HR = 1.10 (95% CI 1.08–1.12) over a 5-year period, respectively. A similar large study using data from Medicare from the United States examined ~ 2.0 million incidences of dementia cases [115]. Per IQR increase in the 5-year average PM2.5 (3.2 µg m−3) and NO2 (22 µg m−3), they found an association with the development of dementia HR = 1.060 (95% CI 1.054–1.066) and with exposure to NO2 HR = 1.019 (95% CI 1.012–1.026), respectively. The authors also observed significant associations between exposure to PM2.5 and the development of Alzheimer’s disease HR = 1.078 (95% CI 1.070–1.086) and NO2 exposure HR = 1.031 (95% CI 1.023–1.039). The results of these new studies lend support to the theory that there is an association between air pollution and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

2.5 Effects of tropospheric ozone and particulates on plants

Photochemical air pollution can damage plants, with potentially adverse effects on agriculture and other natural resources. Ground-level ozone is a particular concern, since numerous studies have demonstrated significant damage [78, 116]. Other air pollutants co-produced with O3, e.g., peroxyacetyl nitrate (CH3C(O)O2NO2) are also phytotoxic, although their specific effects are difficult to separate from those of O3 [117]. The understanding of mechanisms and mitigation of these effects has improved, and some effects of particulates on plants are assessed below.

2.5.1 Effects of tropospheric ozone on health and yields of plants

In the previous Quadrennial Assessment [6], we evaluated the adverse effects of O3 on crop and other plants. We noted that tropospheric O3 could contribute to significant losses in quality and yield of crops, e.g., 10–36% for wheat and 7–24% for rice. The adverse effects of O3 on plants continue to be documented in the literature. A metanalysis of 48 studies on the exposure of soybeans to tropospheric O3 conducted between 1980 and 2019 showed increases in degradation of chlorophyll and foliar injury. Leaf-area was reduced by 21%, biomass of leaves by 14%, shoots by 23%, and roots by 17% [118]. Chronic exposure to O3 of about 150 μg m−3 caused a decrease in yield of seed by 28%. In a study in Argentina [119], exposures of soybeans (a sensitive crop) to O3 at a concentration of 274 μg m−3 for 7 days resulted in a reduction in below-ground biomass of 25%, a 30% reduction of nodule biomass, and a 21% reduction of biological nitrogen fixation. Effects were more severe in tests with soils of low fertility where production of seed and seed protein was reduced by 10% and 12%, respectively. These effects in soybean exposed to O3 at 160 μg m−3 for 7 days were linked to decreases in metabolism of carbon and capacity for detoxification in the roots of soybean [120]. A study on the historical losses to air pollutants in maize and soybean grown in the United States showed that improvements in the control of O3, SO2, PM, and NO2 have improved yields by an average of 20% [121]. Of these pollutants, PM and NO2 appeared to cause more damage than O3 and SO2. Overall, the improvement in yields was equivalent to ca US$ 5 billion.

Observations between 2015 and 2018 in the province of Henan in China [122] showed that annual losses in yield of wheat exposed to O3 at concentrations above 80 μg m−3 were 12.8, 8.9, 10.8, and 14.1%. These were equivalent to annual losses of US$ 2.14, 1.32, 1.68, and 2.16 billion, respectively. A model was developed to extrapolate these losses to other crops in China [123]. Based on a 4-year average of tropospheric concentration of O3, estimated losses in wheat were 50 million tons per year, mostly in winter wheat (48 million tons); 21 million tons in rice; 18 million tons in maize and 1.6 million tons in soybeans [123]. A separate modeling study estimated that current concentrations of O3 reduced yield by 6.9% for rice and 10.4% for wheat [124]. Clearly, tropospheric O3 has significant adverse effects on food security in some countries and this might be exacerbated in the event of super-recovery of stratospheric ozone.

A modeling study on the effects of measured concentrations of O3 on grapes in the Demarcated Region of Douro in Portugal indicated that, in 2 years of high levels of O3, productivity of grapes was reduced by 27% and sugar content by 32% [125]. Similar effects were echoed in other grape-growing regions across the globe [126].

Crops are not the only class of plants to suffer reductions in yields from exposure to air pollutants. Forests are important sources of wood and fiber and can be affected by tropospheric air pollutants such as O3. In an analysis of the impacts of O3 on production of forests in Italy, Sacchelli et al. [127] calculated that the average cost of potential O3 damage to forests in Italy in 2005 ranged from 31.6 to 57.1 million € (i.e., 10–17 € ha−1 year−1). This damage resulted in a 1.1% reduction in the profitable forest areas. Estimated decreases in the annual national production of firewood, timber for poles, roundwood and wood for pulp and paper were 7.5, 7.4, 5.0, and 4.8%, respectively. A study on the effects of O3 on trees in Mediterranean forests in Istria and Dalmatia showed that current levels cause inhibition of growth for two species of oak (Quercus pubescens and Q. ilex) as well as pine (Pinus nigra) [128]. A climatological modeling study in European forests has shown that climate change has lengthened the growing season by ca 7 days decade−1 [129]. Because of this, the total phytotoxic dose of O3 taken up by trees over the season has increased and outweighs the benefits of a decrease in concentration of tropospheric O3 (1.6%) that resulted from measures to control pollution between 2000 and 2014.

Because of their sensitivity, the potential effects of O3 in the environment have been more extensively studied in plants than in animals. However, a recent study has focused on the effects of O3 in amphibians [130]. The authors exposed tadpoles of the midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) to air-borne O3 at concentration up to 180–220 µg m−3 for 8 h per day from an early stage of development (limbs not yet formed) to metamorphosis. This is equivalent to the maximum concentrations observed in the Sierra de Guadarrama Mountains over a period of 10 years. The measured responses were successful development and infection of the developing tadpoles with the aquatic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which causes the disease known as chytridiomycosis. Airborne concentrations of O3 were measured in the exposure chambers but not in the water containing the tadpoles, so that actual dose could not be calculated. Results suggested that, at the greatest air-borne exposure, development of the tadpole was delayed and that susceptibility to Bd was increased. This study is preliminary and further work is needed to elucidate potential effects.

In summary, future changes in UV-B radiation will influence ground-level O3 and other pollutants. The recovery of stratospheric O3 to 1980 levels is expected to contribute 1–2 µg m−3 to ground-level O3 outside major urban areas [14, 15, 36], but super-recovery under some future climate scenarios could lead to larger increases (Sect. 2.2, and Box 1). This could be offset by further reductions in NO and VOC emissions, so the actual O3 concentrations will depend on local and regional air quality control measures, as well as the impacts of climate change and the Montreal Protocol on stratospheric O3. These impacts could affect both food security and forests.

2.5.2 Toxicological mechanisms

Effects of ozone on plants are mediated by the formation of free radicals in the tissues of the plants. Ozone enters the leaf of the plant through the stomata and forms ROS, which include O2•−, H2O2, OH, 1O2, as well as reactive carbonyl species such as malondialdehyde and methylglyoxal [131]. These reaction products damage components of the cells but also stimulate signaling systems, such as the release of isoprene [132] to activate defense mechanisms. These defenses include physical actions, such as closure of the stomata, biochemical responses such as the release of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases to destroy the ROS, and release of chemical buffers, such as ascorbic acid, glutathione, phenolic chemicals, flavonoids, proline [133], and other amino acids, carotenoids, tocopherols, polyamines, and sugars [131].

Some adverse effects of tropospheric air pollutants on plants are indirect. For example, air pollutants can affect visual and chemical signals that mediate interaction between plants, and organisms that depend on plants or that are needed for the sustainability of plant communities [134] (see Fig. 5). For example, tropospheric O3 can destroy or change biogenic volatile chemicals and, thus, interfere with attraction of pollinators or pests to plants [135]. O3 could also interfere with sensory organs and the ability of pollinators to sense sources of nectar or the ability of biological-control organisms to sense their target hosts [134]. Also, physiological responses to damage from O3 might alter the ratios of pigments in plants, the phenology (seasonal development) of flowers and whole plants [136], or the time of flowering, thus affecting host recognition and pollinators. Pollutants may also affect reproduction in plants by directly damaging air-borne pollen through stimulating repair mechanisms and redirecting resources to cell repair rather than reproduction [137, 138]. In addition, the allergenicity of pollen can be enhanced with implications for human health [137].

Sites at which air pollution can affect interactions mediated by olfactory or visual cues between plants and their associated community. A Effects of pollutants on signal-emitting organisms. B The degradation of VOCs by air pollutants and formation of reaction products and secondary organic aerosol (SOA). C Effects on the signal receiving organisms, e.g., pollinating insects. In addition, exposure to air pollution can influence the interactions between herbivores and plants. D From [134], reproduced with permission

2.5.3 Effects of particulates on plants

The effects of PM on plants were previously assessed to be few and minor [5, 6], but new studies suggest they may be important particularly in polluted areas. In a study of water-extractable chemicals collected from PM2.5 samplers on roadsides in Hungary, 13 common roadside plants were tested for sensitivity using the OECD-227 guideline test [139]. Endpoints measured in the study were shoot weight, shoot height, visible symptoms of damage on the plants, growth rate, photosynthetic pigments, and activity of peroxidase enzyme. The authors concluded that particulate pollution derived from traffic added substantial additional stress to communities of plants found on roadsides. The study was conducted during mid-winter and near sources, implying that most of the PM was primary rather than secondary, and hence insensitive to any changes in UV radiation. It is unclear if similar plant damage would have been caused by UV-dependent secondary aerosols.

In another study, the combined effects of ambient atmospheric O3 and particulate matter on wheat were assessed [140]. The cumulative concentration of ambient O3 above the threshold of 80 μg m−3 h−1 during the 4-month study was 453 μg m−3 h−1. Concentrations of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 ranged between 45–412 μg m−3 and 103–580 μg m−3, respectively. Controls were cleaned of particulates and were protected from O3 by treatment with ethylene diurea, a mitigator of ozone-stress. Economic yield was reduced 34% in wheat exposed to O3 and PM, 44% in wheat exposed to PM only and 52% in plants exposed to O3 alone. Similar observations were reported in a modeling analysis of the effects of O3 and PM on the yields of wheat and rice in China [124]. Based on current levels of O3 and aerosols, their results indicated that anthropogenic aerosols reduced yield of rice and wheat by 4.6 and 4.7%, respectively. The authors suggested that this was because of the effect of dimming of photosynthetically active radiation by aerosols but that there were some benefits from cooling and nutrients provided via the aerosols. The losses due to both O3 and aerosols were estimated to be 11.3 for rice and 14.6% for wheat. The relative contributions of primary and secondary PM were not reported, so that the sensitivity to changes in UV radiation remains unclear.

Overall, these results indicate that aerosols and tropospheric O3 alone, or in combination, have adverse effects on plants and yields of crops. The loss from O3 is greater than that from aerosols but they do act additively. With few studies on this interaction, the potential for additive and/or synergistic effects of O3 and particulates, the significance to crop plants and human activities is uncertain. However, it is likely that these effects will be localized and could be mitigated by increased controls of tropospheric air pollutants.

2.6 Self-cleaning capacity of the atmosphere

The hydroxyl radical (OH) is the major oxidant in the troposphere and its concentration largely determines the lifetime of many tropospheric pollutants. It is produced via UV-B photolysis of O3 (see Fig. 1). Hence, increases in the tropospheric concentration of OH are, in part, a consequence of increasing emissions of ODSs. The tropospheric concentration of OH is a balance between OH production and consumption, where both rates are also affected by climate change.

Global mean concentrations of tropospheric OH have been calculated to have changed little from 1850 to around 1980 [141, 142]. However, in the period 1980–2010 the modeled global tropospheric concentration of OH has increased, mainly because of increasing concentrations of precursors of tropospheric O3, and UV radiation [141]. According to the combined output of three computer models (Fig. 6), there was a net increase in OH of about 8% (mean value of the models). The main precursor of tropospheric O3 is NOx, the tropospheric concentration of which has increased over 1980–2010 (Fig. 6). Global emissions of NOx peaked around 2012, followed by reductions [143]. In addition to NOx, also ODSs and factors underlying climate change such as rising water vapor have contributed to the net increase in modeled OH from 1980 to 2010. Increasing atmospheric CH4 was the main factor counteracting the trend of rising OH (by about − 8%, see Fig. 6) in this period.

Relative change in global concentrations of tropospheric OH from 1980 to 2020, estimated with three different Earth System Models (ESMs). The net change in OH (rightmost column) has contributions from increased emissions of nitrogen oxides and other precursors of tropospheric ozone (ΔNOx); increased emissions of methane (ΔCH4); accumulation of ozone-depleting substances now regulated under the Montreal Protocol (ΔODSs); emissions of particulate matter and its precursors (ΔPM); and other undifferentiated changes attributed to underlying climate change (e.g., water vapor), as well as interactions among these separate factors (ΔOther) (modified from [141])

Studies that infer concentrations of OH by the rate of removal of chemicals from the atmosphere have generally indicated a decreasing trend in OH after 2000 [144]. However, the interannual variability in OH from these studies was large, i.e., the difference between modeled and measured OH trends were not statistically significant [141]. For such studies, methyl chloroform (CH3CCl3) is often used [145] to infer concentrations of OH. The drawback of this method is that the emissions (almost entirely anthropogenic) of CH3CCl3 have declined substantially in the last 30 years [145], thus affecting the accuracy and precision of derived amounts of global OH.

Future trends in tropospheric concentrations of OH not only depend on solar UV-B radiation and on the concentration of precursors of OH but also on OH sinks, particularly CO and CH4. As discussed above, the increasing global concentration of CH4 was the main factor counteracting positive modeled OH trends in the period 1980–2010 (Fig. 6). Total global emissions of CH4 are currently ~ 525 Tg year−1 [146]. If emissions of CH4 from anthropogenic and natural sources continue to rise as they have since 2007, this could decrease global mean OH by up to 10% by 2050 [147], increasing the atmospheric lifetime and concentrations of CH4 in a positive feedback. Also, emissions of CO, the major sink of OH, may increase as a result of more frequent and longer lasting wildfires related to climate change. A change in the average concentration of OH in the troposphere would have large impacts on the cleaning capacity of the troposphere.

Finally, we note the importance of reactions between tropospheric OH and gases that affect stratospheric ozone (Fig. 7). These include anthropogenic halogenated organics (the HCFCs and HFCs, specifically selected for their reactivity with OH so that they are removed in the troposphere), as well as gases such as CH4 and VSLSs. Hydroxyl radicals control the tropospheric lifetimes of these gases, and hence their ability to reach the stratosphere. VSLSs are important pollutants since they can reach the lower stratosphere, despite their tropospheric lifetime of less than 6 months, and contribute to depletion of stratospheric O3 [148, 149]. These chemicals are not controlled by the Montreal Protocol and include chlorinated, brominated, and iodinated VSLSs (Cl-VSLSs, Br-VSLSs, and I-VSLSs, respectively). Cl-VSLSs are mostly of anthropogenic origin, while I-VSLSs and Br-VSLSs, particularly bromoform (CHBr3) and dibromomethane (CH2Br2) are mainly produced in biotic processes and are affected by climate change, including increased coastal runoff and thawing of permafrost [148]. The contribution of BrVSLSs to the total stratospheric bromine loading was estimated to be ≈ 25% (in 2016) [150]. The mixing ratio of Br-VSLS at the tropopause has been measured to increase with latitude in the Northern Hemisphere, particularly during polar winter [149] when photochemically driven losses are smallest. This results (via troposphere-to-stratosphere transport) in higher concentrations of Br-VLSLs in the extratropical lower stratosphere, as compared to those in the tropical lower stratosphere [149].

Interacting effects of UV-B radiation and climate change on tropospheric concentrations of OH and on the lifetime of very-short-lived substances (VSLSs). Effects of climate change include more frequent wildfires and thawing of permafrost soils with the formation of thermokarst lakes, which are important sources of CO and CH4, respectively. Increased emissions of CO and CH4 tend to decrease the tropospheric OH concentration, which in turn results in longer lifetime of VSLSs and, thus, a higher probability of stratospheric ozone depletion

The major sink of halogenated VSLSs is reaction with OH. Hence, the tropospheric lifetime of VSLSs mainly depends on the tropospheric concentration of OH. For example, Rex et al. [151] found a lifetime of dibromomethane (CH2Br2) as long as 188 days inside an OH minimum zone over the West Pacific, while outside the OH minimum zone, the lifetime of CH2Br2 was 55 days. In addition to CHBr3 and CH2Br2, methyl bromide (CH3Br) is an ODS. Due to the Montreal Protocol and its Amendments, atmospheric mole fractions of CH3Br have declined considerably and, at present, emissions of CH3Br primarily stem from natural sources [152], with some anthropogenic sources related to commercial quarantine and pre-shipment applications. The production of CH3Br in seawater is a biological process mediated by phytoplankton such as diatoms [153]. The interannual variability of atmospheric CH3Br concentrations cannot be solely explained by changes in the biological production of CH3Br due to changes in sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) and stratification [152]. Also, sinks of CH3Br have to be considered, where the major atmospheric sink of CH3Br is reaction with OH. Nicewonger et al. [152] found a strong correlation between the interannual variability of CH3Br and the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) from 1995 to 2020. About 36% of the variability in global atmospheric CH3Br was explained by the variability in El Niño Southern Ocean (ENSO) during this period, with increases in CH3Br during El Niño and decreases during La Niña [152]. One reason for increases in atmospheric CH3Br concentrations during El Niño years (positive ONI) could be a global reduction in OH during El Niño years. Based on modeling studies for the period 1980 to 2010, Zhao et al. [142] found decreases in global concentrations of OH during El Niño years that were mainly driven by an elevated loss of OH via reaction with CO from enhanced burning of biomass (Fig. 7). The longer the tropospheric lifetime of halogenated VSLSs, the higher is the probability that they reach the stratosphere and contribute to depletion of stratospheric O3 with impacts on ground-level UV-B radiation. Since UV-B radiation, together with tropospheric O3 and water vapor enhance the formation of OH, increased levels of UV-B radiation could counterbalance decreasing concentrations of OH due to wildfires and thawing of permafrost soils (Fig. 7).

2.7 Changes in atmospheric circulation and transport of pollutants

2.7.1 Ozone from the stratosphere

Ozone as an air quality issue has normally been considered as a local or regional issue. However, O3 from the stratosphere is also transported to the troposphere where it contributes an important but variable fraction of O3 at ground level and represents a baseline upon which locally or regionally generated O3 is added. This is known as stratospheric–tropospheric exchange (STE). The magnitude of the contribution of stratospheric O3 to tropospheric O3 is difficult to quantify but important. A comparison of measurements and 3 different models estimated the influence of stratospheric O3 on tropospheric O3, highlighting the challenges of obtaining consistent results [154]. The study estimated the fraction of O3 near the Earth’s surface that can be attributed to O3 transported down from the stratosphere. This was found to vary between 10% year-round in the tropics increasing to greater than 50% at mid to high latitudes in winter.

The amount of O3 transported from the stratosphere to the earth’s surface is likely to change due to human activities. Stratospheric O3 is transported to the troposphere as part of the Brewer-Dobson circulation, which describes the turnover of stratospheric air (Fig. 8). Part of this is the transport of tropospheric air into the stratosphere in the tropics, and the return of (O3-rich) air in the troposphere of the subtropical regions. Recovery of stratospheric O3 because of decreasing release of ODSs would be expected to increase the amount of O3 transported into the troposphere. However, the impact also depends on the strength of the meteorology driving STE, which is sensitive to changes in climate.

Estimates of STE are poorly characterized by observations and atmospheric models. An assessment of amounts of O3 in the troposphere shows that model estimates of STE were around 1000 Tg year−1 O3 for results reported in 1995 but by 2015 models provided estimates approaching 400 Tg year−1, with a multi-model estimate of 535 ± 160 Tg year−1 for the year 2000 [155]. The IPCC AR6 assessment reports a value of 628 ± 800 Tg year−1 for 2010, with the large uncertainty highlighting how poorly this value is known [11]. Other recent estimates include 347 ± 12 Tg year−1 (2007–2010) [156] and 400 ± 60 Tg year−1 (1990–2017) [157].

Typically, the magnitude of the STE is inferred as the difference between the calculated production and loss of O3 (termed the residual) rather than modeling STE transport itself [158]. These production and loss terms are an order of magnitude larger (around 5000 Tg year−1) than the estimated transport [e.g., 159], so that their difference is highly uncertain. A second confounding factor is that models have used different definitions of the upper boundary (tropopause) of the troposphere.

The modeling of the impact of STE on tropospheric O3 for the period 1850–2100 shows a significant decrease in O3 from the stratosphere by the year 2000 [158] (see Fig. 9). A modeling study focusing on the period 1980–2010 calculated a decrease in the transport of O3 from the stratosphere to the troposphere due to the impact of ODSs on stratospheric O3 [160]. The model estimated a 4% decrease (14 Tg O3) in global tropospheric O3 resulting from ODS up until 1994. Another study using measurements of N2O to constrain the atmospheric modeling estimated an average decrease in STE due to the Antarctic ozone hole (1990–2017) of 30 Tg year−1 with a range of 5–55 Tg year−1, depending on year [157].

Drivers of tropospheric ozone concentration (redrawn with permission and assistance from Guang Zeng from Fig. 13, in [158]). The deposition amount is directly related to the concentration of O3 at the surface of the Earth. The two panels represent the output of different chemistry–climate models considered in the study. STE, stratospheric–tropospheric exchange

In contrast, the results of a modeling and observational study of the regional changes in O3 concentration in the troposphere for the period 1980–1990 through to 2000–2010 [154] suggest an increase in the concentration of O3 at the Earth’s surface, but the other studies (noted above) found that stratospheric O3 led to a small increase over this period in the Northern Hemisphere and no significant change in the Southern Hemisphere. Clearly more work is needed in this area.

For the period from 2000 to 2100, substantial increases in the amount of O3 transported from the stratosphere to the troposphere are predicted [158]. Estimates using the output from seven atmospheric models and focusing primarily on RCP6.0, [161] suggest a 10–16% increase in the amount of O3 in the troposphere from STE in the twenty-first century. When assessing the relative importance of changes in GHGs vs ODSs in driving the changes in STE, they did not obtain a consistent picture from the models, although it appears that the two factors are of similar magnitude [161]. However, there is insufficient agreement between models to quantify trends. The net change in the concentration of O3 in the troposphere by 2100 is very dependent on the magnitude of anthropogenic emissions. The decrease in net chemical production (red curve, Fig. 9) is driven by the predicted controls on the emission of air pollutants. Calculations using the RCP8.5 scenario showed a marked increase in the concentration of O3 in the troposphere, with a threefold larger amount of O3 transported from the stratosphere than the RCP6.0 scenario [161]. It is not possible to infer the magnitude of the changes in O3 at ground level from these models, as they report O3 concentrations averaged for the entire vertical extent of the troposphere, and the impact of stratospheric O3 is much larger in the upper troposphere than at the Earth’s surface.

Folds in the tropopause have a direct impact on air quality at ground level. These folds are not uniformly distributed longitudinally [162, 163] and are common over the Eastern Mediterranean, where they have been identified as a significant cause of elevated concentrations of O3 at ground level that are greater than the European Union air-quality standards [164]. The equivalent effect is also observed in the Southern Hemisphere over the Indian and Southern Oceans. A modeling study of tropopause folds for the period 1960–2100, using emissions as specified in RCP6.0 and including stratospheric O3 recovery, suggests that folds will increase during this period. Statistically significant changes in the number of tropopause folds of around 3% have been identified in regions that coincide with a calculated increase of 6 µg m−3 in O3 near the Earth’s surface [165].

Quantifying the transport of O3 from the stratosphere is therefore important to understanding tropospheric air quality but remains difficult. The challenge in measuring and modeling STE of O3 is partially due to the mechanism by which the downward transport occurs. Air rich in O3 is injected into the troposphere at the edges of the tropics via “folds” (Fig. 8), where thin layers of air from the stratosphere are surrounded (vertically) by air from the troposphere and vice versa. These layers then mix. Methods for identifying folds within model output are being improved [e.g., [165] and showing some promising consistency among different models [162].

The modeling of STE is also hampered by the relatively few measurements of the chemical composition and physical structure of the atmosphere in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere. As a result, there is little information that can be used to constrain atmospheric models. Efforts are now underway to use measurements of the chemical composition of air on commercial aircraft to build up a robust climatology, which can help modeling [166]. Similarly, there are ongoing efforts to improve the use of measurements of O3 by satellites in atmospheric modeling [167], and potentially O3 sondes and in situ measurements. Using observations to constrain models introduces sensitivity to changes in quality and calibration of the input data and this requires careful assessment [167, 168] In future, these data should allow better quantification of the changes in tropospheric O3 that are caused by changes in stratospheric O3.

2.7.2 Effects of circulation changes on extreme weather events and air quality

Air quality is also affected by extreme weather events, such as wildfires. Changes in weather patterns, including extreme weather events, are not only caused by climate change but also by polar stratospheric ozone depletion, which strengthens the stratospheric polar vortex. Changing weather patterns due to the Antarctic ozone hole have been observed in the Southern Hemisphere [23, 169, 170]. For example, anomalies in rainfall and droughts in the Southern Hemisphere are correlated with the duration of the Antarctic Ozone hole [171]. In addition to the strength of the stratospheric polar vortex, the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole also affect weather conditions in Australia [172]. Hot and dry weather increases the risk of wildfires. The severe fire season in Australia 2019–2020 led to significant degradation of air quality within Australia and a smoke plume that was traced around the globe [173,174,175]. The likelihood of wildfires is increasing globally, a trend that is expected to continue [176]. However, the recovery of stratospheric O3 should decrease the stability of the Antarctic polar vortex, which should lead to wetter conditions in the Southern Hemisphere in the near future for this region.

Similarly to the effects of the atmospheric dynamics of the Antarctic ozone hole, Arctic stratospheric ozone depletion results in a shift of the Arctic Oscillation (AO) to more positive values (e.g., [177]) and a more zonal Northern Hemisphere jet stream. Consequences are colder than normal surface temperatures in southeastern Europe and southern Asia, but warmer than normal surface temperatures in Western Europe, Russia, and northern Asia [178]. For example, a likely consequence of the unprecedented Arctic stratospheric ozone depletion in spring 2020 was the heat wave in Siberia accompanied by wildfires in this region [179]. Whether such events will occur in the future depends on trends in the emissions of ODSs and GHGs, since GHGs affect the Arctic stratosphere via radiative cooling [180]. Hence, the frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts and therefore wildfires in both hemispheres is influenced by direct effects of climate change and by changes in atmospheric circulation and in polar stratospheric O3. Wildfires decrease tropospheric air quality with the emission of PM, CO, and other tropospheric pollutants, which impact human health.

2.8 Conclusions

Changes in stratospheric O3 concentrations, and thus in ground-level UV-B radiation, affect tropospheric air quality. Poor air quality remains a major health problem globally, despite progress in reducing emissions of primary air pollutants. Much of the impact of air pollutants is due to chemicals produced by UV-B-initiated photochemistry, including O3 and PM, i.e., secondary inorganic and organic aerosols. PM and tropospheric O3 pose a significant health risk. Overall, recovery of stratospheric O3, and hence lower intensity of ground-level UV-B radiation, is expected to slightly improve air quality in cities in mid-latitudes but slightly worsen air quality in rural areas. For PM, the impacts of changes in UV-B radiation on the amount and chemical composition of PM are still poorly understood.

Transport of O3 from the stratosphere into the troposphere adds to tropospheric O3 concentrations. This transport is expected to increase because of the recovery of stratospheric O3 and changes in global circulation driven by climate change. Given the current state of knowledge, estimating the magnitude of these changes remains a significant challenge.

UV-B radiation is also involved in the formation of OH, the major cleaning agent of the troposphere. Hence, UV-B radiation has some beneficial effects on tropospheric air quality. Reaction with OH drives the atmospheric removal of many problematic tropospheric gases including some pollutants and GHGs such as CH4, and VSLSs (noting also that GHGs and VSLSs affect stratospheric O3). Given current global CH4 emission of ~ 500 Tg year−1, a 1% decrease of the global OH concentration would result in an increase of ~ 1% in tropospheric CH4 concentrations, equivalent to a sustained increase in emissions of CH4 of ~ 5 Tg year−1.

The main sink of OH is reaction with CO. An important natural source of CO is wildfires, which have increased in frequency and intensity due to climate change. Hence, UV-B radiation and climate change affect concentrations of tropospheric OH with potential feedbacks on climate change and on stratospheric ozone.

The impact of poor air quality is not limited to human health; it affects plants and other organisms as well. This has had a substantial impact on food production and forests through exposure to ground-level O3. There is also evidence of reduced food production due to PM. The magnitude of these impacts will be altered by climate change and the future evolution of stratospheric O3.

3 Trifluoroacetic acid in the global environment with relevance to the Montreal Protocol

3.1 Background

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is the terminal breakdown product of many fluorinated chemicals, including those that fall under the purview of the Montreal Protocol and its Amendments. Its properties (discussed below) include very low reactivity, high stability, and recalcitrance to breakdown in the environment. This has raised concerns about the use of fluorinated substitutes for the ozone-depleting and the fluorinated greenhouse gases. The formation, fate, and potential effects of TFA has been the remit of the EEAP for the last two decades, and this overview is a continuation of this activity with a primary focus on new information since the last Quadrennial Assessment [6] to the Parties of the Montreal Protocol.

3.1.1 Classification of trifluoroacetic acid as a per- and poly-fluoroalkyl chemical

Trifluoroacetic acid CF3-COOH (CAS# 76-05-1) is a perfluorinated chemical, meaning that, aside from its functional group (-COOH), all hydrogen atoms in the molecule have been replaced with fluorine. The European Chemicals Agency has proposed that this chemical be included in a class, the per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) [181]. Others have suggested that the definition of PFAS should exclude TFA and chemicals that degrade to just give TFA [182]. In 2022, there were 4730 chemicals in the PFAS class, which had been expanded to include all chemicals with at least one aliphatic –CF2– or –CF3 moiety. The PFAS class includes gases (such as those under the purview of the Montreal Protocol), low boiling point liquids, high boiling point liquids and lubricants, and solid polymers used in industry, medicine, and domestic equipment. As has been pointed out [183], a small number (about 256) of these PFAS are currently used commercially and “grouping and categorizing PFAS using fundamental classification criteria based on composition and structure can be used to identify appropriate groups of PFAS substances for risk assessment.” [183] More recently, a majority of a panel of experts agreed that “all PFAS should not be grouped together, persistence alone is not sufficient for grouping PFAS for the purposes of assessing human health risk, and that the definition of appropriate subgroups can only be defined on a case-by-case manner.” [184]. In addition, the majority opinion with respect to toxicology was that “it is inappropriate to assume equal toxicity/potency across the diverse class of PFAS” [184].