Abstract

The paper analyzes subjective poverty in St. Louis County, Minnesota, with the methods of systematic data collection in 2020 and makes a diachronic comparison using the results of a similar survey from 2010. The paper identifies the most important poverty-related items and compares the precise meanings of the results of the 2010 and 2020 surveys. It also aims to find out how the recovery after the recession of 2008 modified perceptions of poverty. It is revealed that poverty in 2020 is mainly associated with items related to material needs. Many of the items mentioned in relation to poverty are related to financial issues, to basic human needs, or to physical safety. The paper concludes that in spite of the economic recovery, subjective poverty did not change significantly in the examined period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of poverty lacks a universally accepted definition. It is difficult to define and measure. The measurement of poverty has been in the focus of both researchers and policy-makers in working out strategies towards the mitigation of poverty. They have lately shown an increasing interest towards subjective poverty, arguing that poverty is not exclusively an objective condition based on the income level needed to satisfy human needs but depends also on people’s values and perceptions (Goedhart et al. 1978; Van Praag et al. 1971; Guagnano et al. 2015).

This study compares poverty interpretation over time in St. Louis County, Minnesota, focusing on how the perception of poverty changed during significant economic changes. The economic crisis started in 2008 had significant effects on social processes as well. As subjective poverty reflects social and cultural values (Samman 2007) and economic development is proved to be associated with cultural changes (Inglehart and Baker 2000), a relevant question is to examine how the recovery from the economic crisis started in 2008 affected the evolution of subjective poverty. By comparing the perception of poverty right after the recession of 2008 (in 2010) and more than a decade after the recovery (in 2020), it becomes possible to reveal whether economic performance has any significant effect on the perception of poverty. Examining the effect of economic conditions on poverty perception is a relevant question also because of the so-called “Minnesota paradox”, which refers to the significant discrepancy between the overall high level of well-being and the large racial differences (Barr 2018). In 2018, Minnesota turned out to be the second best state in the USA to live in according to U.S. News and World Report, while it ranked 47th in employment gap by race, and 38th in income gap by race (Nanney et al. 2019). Employment rates for racial minorities have been among the lowest in the country (Myers and Ha 2018). In addition, racial disparities are transparent in economic indicators (like median income level or poverty rate) and health outcomes (like more lower birthweight), and education attainment.

The study uses the methods of systematic data collection (Weller and Romney 1988) and cultural consensus theory (Weller 2007) to gain information about subjective poverty.

The paper first introduces subjective poverty and explains how it is related to economic performance. Next, the methodology applied to collect primary data about the perception of poverty is described. The “Results” section presents the main findings of the research. The Discussion draws conclusions and makes recommendations for specialists of poverty and decision-makers.

The paper aims to answer the following questions:

-

1.

How was poverty identified and what were the most important poverty-related items in St. Louis County, Minnesota, in 2020, a decade after the recovery from the economic recession of 2008?

-

2.

In 2020, a decade after the recovery from the economic recession of 2008, what are the precise meanings of poverty-related items in cases where there are ambiguities?

-

3.

With recovery after the recession of 2008, how did the perception of poverty change in Minnesota from 2010 to 2020?

Poverty perception

The widely used objective concepts of poverty [like the absolute, the relative measures, or the “capability poverty” defined by Sen (2009)] have several drawbacks (Thorbecke 2013). They do not take into account the psychological dimension of well-being, even when this dimension is important for explaining the phenomenon of poverty and for developing successful poverty reduction strategies (Kakwani and Stiber 2007). Objective poverty concepts often also ignore the heterogeneities of the individuals’ well-being (Wang et al. 2020) as well as non-material needs (Townsend 1979).

Because of the abovementioned limitations of objective poverty, the subjective definition of poverty has become increasingly important. It is also beneficial to use it for identifying the poor and to elaborate poverty reduction strategies because individuals can provide reliable information about their well-being. (Zhou and Yu 2017; Deaton 2018; Wang et al. 2020).

Two interpretations exist in the literature for subjective poverty. On the one hand, subjective poverty expresses the individual's beliefs of his or her own financial situation and where s/he is situated in the system of income inequalities. On the other hand, it expresses what the individual thinks about poverty and social exclusion. Although the subjective concept of poverty cannot directly form the basis of government decisions, it can and should play an important role in understanding social values, beliefs, and behaviors (Samman 2007).

The perception of poverty is usually measured with questionnaire surveys. Four types of questionnaires have been used when analyzing subjective poverty:

-

Van Praag (1968, 1982) used the Income Evaluation Question (IEQ) in his analysis for European countries;

-

Goedhart et al. (1977) developed the Minimum Income Question (MIQ) for their analysis in the USA. This questionnaire was later modified by Garner and Short (2005) to Minimum Spending Questions (MSQ).

-

Deleeck and Van den Bosch (1992) developed the Social Policy Question to study subjective poverty.

-

Siposne Nándori (2011, 2014, 2022) applied cultural consensus theory and the methods of systematic data collection to develop a survey to analyze subjective poverty.

Relationship between economic development and poverty perception

The relationship between economic development and the perception of poverty can be described with set-point theory and modernization theory.

Set-point theory, which originated from dynamic equilibrium modeling and became again popular after 2008 due to the economic crisis (Cummins et al. 2014), posits that the subjective well-being of individuals depends on their social, economic, and cultural backgrounds, which are influenced by external positive and negative effects. These effects are generated by either macro processes (like being promoted or laid off) or by individual events (like getting married or having children). These events can deviate average well-being in the short run, but it will return to its typical range in the long run due to adaptation (Headey et al. 2014; Ivony 2018). Headey et al. (2014) analyzed subjective well-being using long-running panel data from Europe and Australia (the German Socio-Economic Panel, the British Household Panel Survey and the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics Survey in Australia) and concluded that life satisfaction of the majority of the adults did not change in the long run. Kubiszewski et al. (2020) analyzed life satisfaction of adults from Australia and used panel data from Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics Survey. They examined the standard deviation of year-on-year life satisfaction of individuals, and concluded that the life satisfaction of the individuals return to a certain level even after major life events. They found that set-point theory applies more to individuals with a higher level of life satisfaction. When analyzing subjective poverty in Hungary before and after the economic recession of 2008, Ivony (2018) used pooled cross-sectional data from the European Social Surveys and a multidimensional quality of life index and applied difference-in-difference method. She found that the average subjective quality of life did not change significantly from 2007 to 2012. Her findings also support set-point theory.

The relationship between economic background and poverty perception can also be derived from the relationship between economic and cultural values, taking into account that the perception of poverty is dependent on values and beliefs. Modernization theory posits that economic and cultural changes are correlated with each other. Inglehart and Baker (2000, p. 21) says that “economic development is linked with coherent and, to some extent, predictable changes in culture”. Evidence from the World Value Surveys supports the fact that economic development is associated with changes in cultural values, and beliefs. In their analysis, Inglehart and Baker (2000) used two indices to measure economic development: annual per capita gross national product, and the survival/self-expression (associated with the rise of the service economy) and the traditional/secular dimensions (linked with the transition from agricultural societies where traditional values are dominant to industrial societies associated with secular values). Inglehart (2000) argued that with growing real-income level, post-materialist values became dominant in advanced societies. He differentiates two hypotheses. The scarcity hypothesis posits that the value priorities of the individuals largely depend on their socioeconomic environment: growing real-income level strengthens post-materialist values, while economic recession is associated with an increased importance of materialist values. According to the socialization hypothesis, however, adjusting cultural values to socioeconomic environment is not possible in the short run as adults’ fundamental values rarely change and a new generation needs to be grown up to make the changes of values, and beliefs possible. Li and Shi (2019), analyzing data from 2010 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) and conducting multi-factor, multi-level dynamic framework, also argued that subjective well-being did not change with economic growth in the short run.

Methodology

According to the methodology generally applied in the literature (Wang et al. 2020), subjective poverty was measured with questionnaire surveys, often supplemented with a preliminary interview. Data were collected in St. Louis County, Minnesota.

The applied methodology was elaborated within the framework of cultural consensus theory and the methods of systematic data collection. These methods were used to examine subjective poverty in Minnesota because:

-

Methods of systematic data collection, referring to the same set of questions asked from each informant, decrease the sample size required in social science research in a revolutionary way, while maintaining the reliability of the results as high as in the case of traditional research techniques.

-

These methods make the comparison over time possible as subjective poverty was examined with the same methods in 2010 and 2020 (for details of the 2010 data collection refer to Siposne Nandori 2014).

The preliminary interview, called “free listing” in the literature, aimed at eliciting a list of poverty-related items (Weller and Romney 1988) so that the first research question could subsequently be answered. The preliminary interview included questions like: “What do you think poverty means?” “Who do you think are poor?” “Do you know any poor people?” “Why do you think they are poor?”.

Weller (2007) states that the sample size is required to be at least 30 and the minimum number of informants needed for free listing depends on the cultural competence of the informants. Accordingly, the sample size for free listing was 30 in 2010 and 40 in 2020. Multistage sampling with stratification was used to select the informants. Details of sampling methods and sample size parameters are discussed in Siposne Nandori (2022).

The poverty-related items elicited in the preliminary interview can be used in the final step of the data collection that aims to order these items from the one most often related to poverty to the one less often related to poverty and to find the precise meaning of these items in cases where there are any ambiguities. Based on the free listing results, the sample size needed for further research was defined using the guidelines of the consensus theory. Using a binomial test, random answers were first distinguished from strong beliefs so that they can be excluded from the calculation of the informants’ average competence level. Applying Boster’s (1983) guidelines, the average competence level turned to be around 0.7 in 2010 and 0.6 in 2020. Taken into account that 0.99 confidence level was applied and at least 99% of the questions should have been classified correctly, the necessary sample size was 13 in 2010 and 20 in 2020, with reference to Weller and Romney (1988, p. 77). Informants were selected in the same way as for free listing (for details refer to Siposne Nandori 2022) (Table 1).

The frequencies of the poverty-related items mentioned by the informants were used to find the most important poverty-related items in St. Louis County, Minnesota. This gives the answer for the first research question.

In the final step of the data collection, formal interviews were conducted, during which each informant was asked the same set of questions. Quicksort was used to order the poverty-related items. To find the perceived precise meaning of the items where there can be ambiguities, rating scales were applied (Weller and Romney 1988). Based on the results of the rating scales, statistical estimations (with 95% confidence interval) were carried out to find the answer for the second research question.

Free listing was conducted in January and February 2020, and formal interviews were carried out in February and March 2020. Data from Wave 2 were compared to the results of Wave 1 (carried out in 2010). Both Waves of data collection were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines applicable when human participants are involved (Declaration of Helsinki).

To answer the third research question, a comparison of the results of the two Waves was necessary. To do so, F test was used to test the equality of variances and t test was used to test the equality of means. Subjective poverty in 2010 and in 2020 was compared following the idea of modernization theory by assigning poverty-related items into materialist and post-materialist values. To do so, the Maslow (1943) hierarchy was used, which represents the needs of human beings in a pyramid with the basic human needs at the bottom and the esteem needs at the top:

-

Self-actualization (beauty, faith, love);

-

Ethical needs (justice, reasonableness, respectability, reliability);

-

Social needs (belonging, care, respect, self-esteem, respect by others);

-

Material needs (air, water, food, reproductivity, physical safety).

He argues that to rise to the next stage of human needs, lower–level needs must be satisfied. Post-materialist values associated with economic development create higher–level needs, while economic decline is associated with an increased focus on needs at the lower level of the hierarchy.

Results

Subjective poverty in 2020

The research first aimed to find out the public perception of poverty in St. Louis County, Minnesota. To answer the first research question, free listing was used that elicited a total of 47 items, which was shortlisted to 18 (Table 2) following the guidelines of de Munck and Sobo (1998). “Addiction” was mentioned as “drug” or “alcohol” by some informants. The term “addiction” was used for all these items because this is the broader term that incorporates the others. “Born into poverty” was also expressed as “perpetuated poverty” or “generational poverty”. In the final stage of the research, the term “born into poverty” was applied as it was considered to be the most easily understandable for anyone. “Crime” or “violence” were also called “breaking the law”. “In debt” incorporates items like “no savings”. “Lazy to work” was expressed as “no work ethic” by some of the informants. “Living from paycheck to paycheck” was also called “cannot make ends meet”. Informants referred to “poor health” in many ways like “struggling with physical health” or “mental illness”. “Poor diet” refers to “problems with food” and “malnutrition” as well. “Problems with shelter” includes the problem of “homelessness”. “Problems with transportation” was also mentioned as “no vehicle” or “no bus access to education”. “Social benefits” was sometimes called as “food stamps” or “relying on government assistance”. Most citizens still used the term “food stamps” in spite of the fact that the name changed to The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in 2008 (A Short History of SNAP). “Unfavourable circumstances” gather items like “less buying power”, and “inflated costs of living”.

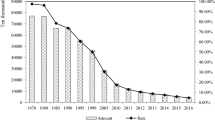

The rank order for each subject ranges from 1 (item most closely or most often related to poverty) to 18 (item least closely or least often related to poverty). The 21 scores elicited by the 21 informants for each item were added up. The highest score belongs to the item less closely related to poverty, while lower scores belong to items more closely related to poverty. Figure 1 shows the final rank order of the items. The name of the items are the ones from Wave 1. Accordingly, “cannot make ends meet” refers to „living from paycheck to paycheck” in 2020, “cycle of poverty” refers to “born into poverty”, “racism” is included in “discrimination”, the item “social benefits” is considered the same as “eligibility for the welfare system”, and “laziness” and “lazy to work” are considered the same. Moreover, “limited opportunities” refer to “lack of opportunities”, while “loss of work” and “no job” are considered the same. The item “poor economy” is considered the same as “unfavourable circumstances (like high prices)”.

“Low income level”, “cannot make ends meet”, “no job”, and “cycle of poverty” are among the items most closely related to poverty, while “poor diet”, “discrimination”, “crime”, and “laziness” are the least closely related to it. The figure shows that 11 items were part of the list in 2010 as well. Some of the joint items (like “no job”, “poor health”, or “addiction”) have similar score values. To test whether the score values are significantly different between 2010 and 2020, t tests are used in Sect. 4.2.

In the case of the items where there could be any ambiguities about their perceived precise meaning [low income level, number of connections (people they could count on), number of children, and education level] rating scales were used to answer the second research question. Number of connections, and number of children were not listed in quicksort. They were used in rating scales because these two items were examined in Wave 1 and checking whether their meanings had changed was possible in this way.

Based on the questionnaire (Fig. 2) results, the perceived meaning of the poverty-related items could be determined. To do so, 0.05 significance level was applied (Table 3). In the case of education level, the scale used in 2020 had 14 points, while the scale of 2010 had 15 points, separating 10th grade and 11th grade. When interpreting the results, this should have been taken into consideration.

As for income, the subjective poverty line was between $ 9 and $ 11 in 2010 and between $ 13 and $ 17 in 2020 in per capita hourly net income. The increase seems to be considerable. In the case of connections, most people were considered poor if they could count on fewer than two people in 2010. This threshold was increased to between two and four persons. This increase is also remarkable. As far as large families are concerned, people thought that most of the large families were poor because of the high number of children when they were raising more than two to four children in 2010. This poverty line was lowered to one to three children by 2020. It implies that having only one or two children contributed to impoverishment in 2020, while bringing up at least two children were necessary to have a great probability of impoverishment ten years earlier. In the case of educational attainment, people with a less than 9th grade level to high school graduate were most likely to become poor in 2010. This threshold only slightly changed by 2020 as the lower limits referred to 9th grade and the upper limits referred to 11th grade in both Waves (refer to Table 3). If you had not graduated from high school (that is, you only finished 11th grade or less), you were more likely to become poor in 2020 than in 2010.

Changes in subjective poverty from 2010 to 2020

To answer the third research question and to find out how the perception of poverty changed in Minnesota from 2010 to 2020 with recovery after the recession of 2008, the results of the two Waves were compared. A total of 21 items were ranked in 2010 and 18 in 2020. Most of the items can be categorized as items related to material needs. This group of items includes money-related items (“low income level”, “eligibility for the welfare system”, “in debt”, “expensive health care”, “cannot make ends meet”), items related to child rearing (“parents low interest in their kids” or “large family”), to physical safety (“crime”), and to basic human needs (“no access to basic needs”, “illness”, “disability”, “poor diet”, “problems with shelter”, and “problems with transportation”). One item (“no connections”) is grouped as related to social needs, while another item (“discrimination”) is classified as ethical need. Three items (“no plans for the future”, “lack of ability to improve culturally or spiritually”, and “lack of opportunities”) were interpreted as needs for self-actualization. Provided that the remaining items (“no job”, “addiction”, “minimal education”, “laziness”, “cycle of poverty”, “poor economy”, and “not using some of your resources”) cannot be assigned to one of the needs unambiguously, they were not taken into consideration in this part of the analysis.

Comparison was possible for the 14 items mentioned in the preliminary interviews to both Waves. Six of these items belong to material needs, one for ethical needs, and one for self-actualization. The only item related to social needs and two items belonging to self-actualization were ranked only in Wave 1. To compare “no access to basic needs”, three items (“poor diet”, “problems with shelter”, and “problems with transportation”) were averaged from the 2020 list. Similarly, “poor health” and “disability” were aggregated from the 2010 list to get one single item comparable with the “poor health” from 2020.

Renumbering scores of the 14 items using numbers from 1 to 14 allowed comparison with F and t tests (Table 4). At the 5% significance level, the position of two items changed significantly from 2010 to 2020. “Low income level” became more closely linked to poverty as its score fell from seven to three. “No access to basic needs”, however, became less closely linked to poverty (its ranking increased from five to eight). The extent to which other items are linked to poverty did not change significantly. It does not support the scarcity hypothesis and suggests that the socialization hypothesis could be true.

When comparing the rating scale results of the two Waves (Table 5), significant changes could be found at the 5% significance level in the income level, and in the number of connections. The income level considered to be a poverty threshold significantly increased. So did the number of connections necessary to avoid poverty. While the presence of two friends who were willing and able to help could protect the individual from becoming poor in 2010, having only three such persons on average still posed a significant risk of poverty in 2020. For the two other examined indicators, the equality of means could be assumed between the two Waves.

Discussion

Subjective poverty was analyzed with cultural consensus theory and the methods of systematic data collection in St. Louis County, Minnesota.

Related to the first research question, we found that poverty in 2020 was mainly associated with items related to material needs. Many of the items mentioned in connection with poverty related to financial issues (like low income level, indebtedness, social benefits, cannot make ends meet, or expensive health care), to basic human needs (like problems with shelter, poor diet, problems with transportation, or poor health), or to physical safety (like crime).

The perceived precise meanings of some poverty-related items needed further specification (second research question). Rating scales were used to identify them. A survey carried out ten years earlier with the same methodology made it possible to examine how the perception of poverty changed over time. The subjective poverty line in terms of income level was $ 15 per capita hourly net income on average. This significantly increased since 2010 when its value was $ 10. The number of connections necessary to protect individuals from becoming poor also increased remarkably. In 2010, two friends who were able and willing to help were enough for an individual to avoid impoverishment. By 2020, however, the limit increased to three persons on average. It implies that the perceived protecting power of connections had decreased in the examined decade.

The analysis comparing the poverty-related items (third research question) in the two Waves revealed that in spite of the economic growth and the recovery after the global economic crisis from 2010 to 2020, the importance of the needs of human being at the different levels did not change. In both Waves, many poverty-related items belonged to material needs. Only some of the poverty-related items can be categorized as higher level needs of human beings (the needs of human being with the poverty-related items belonging to each of them in both Waves of data collection can be seen in Fig. 3). This finding supports the socialization hypothesis. The time which passed between the two Waves might not have been long enough to change the basic values of the population and therefore to modify the perception of poverty.

The time which passed between the two Waves, however, was long enough to test set-point theory. The findings of the research affirmed that individuals’ well-being were close to the „set-point” range in the long run. These results are in line with set-point theory.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barr K (2018) Addressing the Minnesota Paradox. https://www.propelnonprofits.org/blog/addressing-minnesota-paradox/. Accessed 30 Jan 2023

Cummins RA, Li N, Wooden M, Stokes M (2014) A Demonstration of set-points for subjective wellbeing. J Happiness S 15(1):183–206

de Munck VC, Sobo EJ (1998) Using methods in the field: a practical introduction and casebook. Altamira Press, Walnut Creek

Deaton A (2018) What do self-reports of well-being say about life-cycle theory and policy? J Pub Econ 162:18–25

Deleeck H, Van den Bosch K (1992) Poverty and adequacy of social security in Europe: a comparative analysis. J Eur Soc Pol 2:107–120

Garner TI, Short KS (2005) Personal assessments of minimum income and expenses: What do they tell us about ‘minimum living’ thresholds and equivalence scales? Working Papers 379, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Goedhart T, Halberstadt V, Kapteyn A, van Praag B (1977) The Poverty Line: Concept and Measurement. The J Hum Resources, 12(4):503-520.

Goedhart T, Halberstadt V, Kapteyn A, Van Praag B (1978) The poverty line: concept and measurement. J Hum Resour 12(4):503–520

Guagnano G, Santarelli E, Santini I (2015) Can social capital affect subjective poverty in Europe? An empirical analysis based on a generalized ordered logit model. Soc Ind Res 128(2):881–907

Headey B, Muffels R, Wagner GG (2014) National panel studies show substantial minorities recording long-term change in life satisfaction: implications for set-point theory. In: Sheldon KM, Lucas RE (eds) Stability of happiness, theories and evidence on whether happiness can change. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 101–126

Inglehart R (2000) Globalization and Postmodern Values. Washington Q 23(1):215–228

Inglehart R, Baker WE (2000) Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am Soc Rev 65:19–51

Ivony É (2018) Changes in subjective quality of life after the economic crisis in Hungary. Corvinus J Sociol Soc Policy 9(2):157–178

Kakwani N, Stiber J (2007) The many dimensions of poverty. United Nations development programme. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Kubiszewski I, Zakariyya N, Costanza R, Jarvis D (2020) Resilience of self-reported life satisfaction: a case study of who conforms to setpoint theory in Australia. PLoS ONE 15(8):e0237161

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 50(4):370–396

Myers SL Jr, Ha IR (2018) Neutrality rationalizing remedies to racial inequality. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham

Nanney MS, Myers SL Jr, Xu M, Kent K, Durfee T, Allen ML (2019) The Economic benefits of reducing racial disparities in health: the case of Minnesota. Int J Env Res Public Health 16(5):742–755

Samman E (2007) Psychological and subjective well-being: a proposal for internationally comparable indicators. Oxford Dev Studies 35(4):459–486

Sen A (2009) The idea of justice. Allen Lane, London

A Short Story of SNAP. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/short-history-snap#. Accessed 20 Oct 2022

Siposne Nandori E (2011) Subjective poverty and its relation to objective poverty concepts in Hungary. Soc Ind Res 102(3):537–556

Siposne Nandori E (2014) Interpretation of poverty in St. Louis County. Minnesota App Res Quality Life 9:479–503

Siposne Nandori E (2022) Individualism or structuralism-differences in the public perception of poverty between the United States and East-Central Europe. J Pov 26(4):337–359

Thorbecke E (2013) Multidimensional poverty conceptual and measurement issues. In: Kakwani N, Silber J (eds) The many dimensions of poverty. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 3–19

Townsend P (1979) Poverty in the United Kingdom: a survey of household resources and standards of living. University of California Press, Berkeley

Van Praag BMS (1968) Individual welfare functions and consumer behavior: a theory of rational irrationality. North-Holland Pub. Co., Amsterdam

Van Praag BMS (1971) The welfare function of income in Belgium: an empirical investigation. Eur Econ Rev 2:337–369

Van Praag BMS, Hagenaars AJM, van Weern H (1982) Poverty in Europe. Rev Inc Wealth 28(3):345–359

Wang H, Zhao Q, Bai Y (2020) Poverty and subjective poverty in rural China. Soc Indic Res 150:219–242

Weller SC (2007) Cultural consensus theory: applications and frequently asked questions. Field Methods 19(4):339–368

Weller SC, Romney AK (1988) Systematic data collection. Qualitative Res methods. Volume 10, Sage Publications, Newbury Park

Zhou S, Yu X (2017) Regional heterogeneity of life satisfaction in urban China: evidence from hierarchical ordered logit analysis. Soc Ind Res 132:25–45

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Miskolc. This work was supported by Tempus Public Foundation (Tempus Közalapítvány) under Hungarian State Eötvös Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed to the whole process of the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable when human participants are involved (Declaration of Helsinki).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians for participation in the study. They had the opportunity to ask questions before deciding to take part in the survey. They understood that their participation was voluntary. Their answers were collected anonymously.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siposné Nándori, E., Roufs, T.G. The effect of economic conditions on poverty perception in Minnesota. SN Soc Sci 3, 189 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00773-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00773-w