Abstract

Background

Poor neoplastic differentiation contributes to the rapid progression of uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC). Thus, it is essential to identify candidate genes, clarifying the carcinogenesis and progression of UCEC.

Methods

We screened genes that affect differentiation and prognosis in UCEC. Least absolute selection and shrinkage operator (LASSO) regression, univariate Cox, and multivariate Cox proportional risk regression analyses were performed to screen out γ-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) as the candidate gene. The clinical value of GGH on prognosis was evaluated. The relationship between GGH and immune infiltration was assessed by CIBERSORT, EPIC, ssGSEA, unsupervised clustering and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Additionally, we investigated the effect of GGH knockdown in vitro.

Results

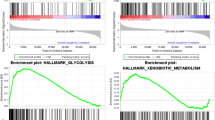

Among the GGH, CDKN2A, and SIX1 genes, the impact of GGH was predominant on immune infiltration in UCEC. A nomogram containing GGH and other clinical features showed good predictive performance via curve analysis (DCA). In the functional analysis, GGH affected differentiation, tumour proliferation, and immune regulation. The immunosuppressive components were enriched in the GGH-high group, with poor immunotherapy efficacy. The study suggests that GGH may influence the progression of UCEC by regulating the glycolytic process.

Conclusions

GGH is closely associated with various immune cell infiltrations. Our study demonstrates the prognostic role of GGH in carcinogenesis in UCEC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its additional files). The data analyzed in this study are available in public databases. TCGA and GTEx data were obtained from the UCSC XENA database (UCSC XENA: https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/, TCGA: http://www.cancer.gov/, GTEx: https://gtexportal.org/). Validation data and immunotherapy data were obtained from the GEO and TIDE databases (GEO: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, TIDE: http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/). The methylation data were obtained from MEXPRESS (http://mexpress.be).

Code Availability

The codes are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Abbreviations

- GGH :

-

Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase

- UCEC :

-

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- GO :

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG :

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- OS :

-

Overall survival

- DFS :

-

Disease free survival

- PFS :

-

Progression free survival

- DSS :

-

Disease specific survival

- TCGA :

-

The cancer genome atlas

- GTEx :

-

Genotype-tissue expression

- AUC :

-

Area under curve

- ROC :

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- WGCNA :

-

Weighted gene coexpression network

- Lasso :

-

Least absolute selection and shrinkage operator

- DNMT :

-

DNA methyltransferase

- SNP :

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- KM :

-

Kaplan-Meier

- GEO :

-

Gene expression omnibus

- PD :

-

Progressive disease

- SD :

-

Stable disease

- PR :

-

Partial response

- CR :

-

Complete response

- OCLR :

-

One-class logistic regression

- mRNAsi :

-

Gene expression-based stemness index

- DEGs :

-

Differentially expressed genes

- GSEA :

-

Gene set enrichment analysis FDR: false discovery rate

- ssGSEA :

-

Single sample GSEA

- TMB :

-

Tumor mutation burden

- MSI :

-

Microsatellite instability

- TIDE :

-

Tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion

- TMB-H :

-

Tumor mutational burden-High

- MMR :

-

Mismatch repair

- TME :

-

Tumor microenvironment

- ICIs :

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- ORR :

-

Objective response rate

- DCs :

-

Dendritic cells

- iDCs :

-

Immature dendritic cells

- aDCs :

-

Activated dendritic cells

- NKs :

-

Natural killer cells

- NK CD56dim cells :

-

Natural killer CD56dim cells

- NK CD56bright cells :

-

Natural killer CD56bright cells

- Th1 :

-

T helper 1

- Th2 :

-

T helper 2

- 5-FU :

-

5-Fluorouracil

- CTX :

-

Cyclophosphamide

- Tγδ :

-

T gamma delta

- Tcm :

-

T central memory

- Tem :

-

T effector memory

- Tfh cells :

-

T follicular helper

- ICB :

-

Immune checkpoint blockade

- ACC :

-

Adrenocortical carcinoma

- BLCA :

-

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA :

-

Breast invasive carcinoma

- CESC :

-

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CHOL :

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD :

-

Colon adenocarcinoma

- DLBC :

-

Lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA :

-

Esophageal carcinoma

- GBM :

-

Glioblastoma multiforme

- HNSC :

-

Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma

- KICH :

-

Kidney Chromophobe

- KIRC :

-

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP :

-

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- LAML :

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LGG :

-

Brain lower grade glioma

- LIHC :

-

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- LUAD :

-

Lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC :

-

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MESO :

-

Mesothelioma

- OV :

-

Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

- PAAD :

-

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG :

-

Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma

- PRAD :

-

Prostate adenocarcinoma

- READ :

-

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- SARC :

-

Sarcoma

- SKCM :

-

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- STAD :

-

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TGCT :

-

Testicular germ cell tumors

- THCA :

-

Thyroid carcinoma

- THYM :

-

Thymoma

- UCS :

-

Uterine Carcinosarcoma

- UVM :

-

Uveal Melanoma

References

Crosbie EJ, Kitson SJ, McAlpine JN, Mukhopadhyay A, Powell ME, Singh N. Endometrial cancer. Lancet (London, England). 2022;399(10333):1412–28.

Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel P, Martinez A, Kempson R. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a highly malignant form of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(2):93–108.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33.

Panetta JC, Wall A, Pui CH, Relling MV, Evans WE. Methotrexate intracellular disposition in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a mathematical model of gamma-glutamyl hydrolase activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2423–9.

Kim SE, Hinoue T, Kim MS, Sohn KJ, Cho RC, Cole PD, et al. γ-Glutamyl hydrolase modulation significantly influences global and gene-specific DNA methylation and gene expression in human colon and breast cancer cells. Genes Nutr. 2015;10(1):444.

Shubbar E, Helou K, Kovács A, Nemes S, Hajizadeh S, Enerbäck C, et al. High levels of γ-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) are associated with poor prognosis and unfavorable clinical outcomes in invasive breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:47.

Rots MG, Pieters R, Peters GJ, Noordhuis P, van Zantwijk CH, Kaspers GJL, et al. Role of folylpolyglutamate synthetase and folylpolyglutamate hydrolase in methotrexate accumulation and polyglutamylation in childhood leukemia. Blood. 1999;93(5):1677–83.

Vivian J, Rao AA, Nothaft FA, Ketchum C, Armstrong J, Novak A, et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):314–6.

Sun D, Wang J, Han Y, Dong X, Ge J, Zheng R, et al. TISCH: a comprehensive web resource enabling interactive single-cell transcriptome visualization of tumor microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1420–30.

Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2016;32(18):2847–9.

Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565–74.

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47.

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–7.

Walter W, Sánchez-Cabo F, Ricote M. GOplot: an R package for visually combining expression data with functional analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2015;31(17):2912–4.

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–50.

Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559.

Langfelder P, Horvath S. Fast R functions for robust correlations and hierarchical clustering. J Stat Softw. 2012;46(11):i11-37.

Csárdi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems. 2006;1695(5):1–9.

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28(11):1747–56.

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–4.

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):l1.

Koch A, De Meyer T, Jeschke J, Van Criekinge W. MEXPRESS: visualizing expression, DNA methylation and clinical TCGA data. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):636.

Koch A, Jeschke J, Van Criekinge W, van Engeland M, De Meyer T. MEXPRESS update 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W561–5.

Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2011;27(12):1739–40.

Thienpont B, Steinbacher J, Zhao H, D’Anna F, Kuchnio A, Ploumakis A, et al. Tumour hypoxia causes DNA hypermethylation by reducing TET activity. Nature. 2016;537(7618):63–8.

Danaher P, Warren S, Lu R, Samayoa J, Sullivan A, Pekker I, et al. Pan-cancer adaptive immune resistance as defined by the Tumor Inflammation Signature (TIS): results from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):63.

Wei J, Huang K, Chen Z, Hu M, Bai Y, Lin S, et al. Characterization of glycolysis-associated molecules in the tumor microenvironment revealed by pan-cancer tissues and lung cancer single cell data. Cancers. 2020;12(7):1788–810.

Malta TM, Sokolov A, Gentles AJ, Burzykowski T, Poisson L, Weinstein JN, et al. Machine learning identifies stemness features associated with oncogenic dedifferentiation. Cell. 2018;173(2):338-54.e15.

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612.

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7.

Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4):782–95.

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1550–8.

Lánczky A, Győrffy B. Web-based survival analysis tool tailored for medical research (KMplot): Development and implementation. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e27633.

Wilkerson MD, Hayes DN. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2010;26(12):1572–3.

Makker V, MacKay H, Ray-Coquard I, Levine DA, Westin SN, Aoki D, et al. Endometrial cancer. Nat Revi Dis Prim. 2021;7(1):88.

Ventriglia J, Paciolla I, Pisano C, Cecere SC, Di Napoli M, Tambaro R, et al. Immunotherapy in ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;59:109–16.

Melling N, Rashed M, Schroeder C, Hube-Magg C, Kluth M, Lang D, et al. High-level γ-glutamyl-hydrolase (GGH) expression is linked to poor prognosis in ERG negative prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):286–300.

Garnis C, Buys TP, Lam WL. Genetic alteration and gene expression modulation during cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:9.

Vanderstraeten A, Tuyaerts S, Amant F. The immune system in the normal endometrium and implications for endometrial cancer development. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;109:7–16.

Kondratiev S, Sabo E, Yakirevich E, Lavie O, Resnick MB. Intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocytes as a prognostic factor of survival in endometrial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(13):4450–6.

Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science (New York, NY). 1956;123(3191):309–14.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant from Anhui Natural Science Foundation Youth Program (2008085QH424). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cheng Zhu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Yishan Du, Qian Huai and Nana Fang: Validation, Software, Methodology. Jing Yang: Validation, Writing—review & editing. Xingyu Li, Wentao Xu and Yanyan Zhang: Writing—review & editing. Xu Zhang and Hanren Dai: Validation, Methodology. Xiaolei Li, Hua Wang and Ying Dai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval number: PJ2023-01-15). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

43032_2023_1363_MOESM2_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 2 Enrichment analysis of differential genes in different degrees of differentiation in UCEC. (a) Volcano plot of DEGs between highly differentiated and poorly differentiated patients. (b) GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in poorly differentiated patients. (c) GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in highly differentiated patients. (d–g) GSEA enrichment analysis of all genes in highly differentiated and poorly differentiated patients. (JPG 548 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM3_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 3 Prognostic analysis of genetic signature models for supplementary materials. (a) Risk score, survival time and expression profile heat map for 3-gene prognosis. (b) Prognostic model for KM survival analysis. (c) Time-dependent ROC analysis of predictive models. (JPG 388 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM4_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 4 Association of GGH, CDKN2A and SIX1 with immune infiltration. (a) Correlation of GGH expression with stromal scores. (b) Correlation of SIX1 expression with stromal scores. (c) Correlation of CDKN2A expression with stromal scores. (d) Heat map of immune infiltration in GGH high expression versus low expression groups (CIBERSORT algorithm). (e) Heat map of immune infiltration in SIX1 high expression versus low expression groups (CIBERSORT algorithm). (f) Heat map of immune infiltration in SIX1 high expression versus low expression groups (CIBERSORT algorithm). (g) Heat map of immune infiltration in CDKN2A high expression versus low expression groups (CIBERSORT algorithm). (i) Immune infiltration abundance of each endometrial cancer sample in TCGA (CIBERSORT algorithm). (JPG 869 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM5_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 5 Relationship between GGH expression and clinical characteristics of patients with endometrial cancer. (a) clinical stage, (b) histological type, (c) histological grade, (d) race, (e) Tumor Invasion, (f) BMI, (g) age, and (h) Menopause status. (JPG 559 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM6_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 6 Single-Cell Analysis of GGH in Cancers. (a) Heat map of GGH expression in different single cell datasets. (b) Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE149652 BLCA dataset. (c) Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE139555 CRC dataset. (d)Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE149771 CRC dataset. (e) Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE118056 MCC dataset. (f) Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE121636 KIRC dataset. (g) Distribution of different cell types and GGH expression in the GSE150430 NPC dataset. (JPG 482 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM7_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 7 Prognostic analysis of GGH in pan-cancer. (a-c) Forest plots showing the prognostic analysis between GGH expression levels and pan-cancer PFS (a), DFS (b) and DSS (c). (d) PFS in patients with high versus low GGH expression in endometrial cancer. (e) DFS of patients with high versus low GGH expression in endometrial cancer. (f) DSS in patients with high versus low GGH expression in endometrial cancer. (g) Time-dependent ROC curves of PFS in patients with endometrial cancer. (h) Time-dependent ROC curves between DFS in patients with endometrial cancer. (i)Time-dependent ROC curves of DSS in patients with endometrial cancer. (JPG 841 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM8_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 8 Relationship between GGH expression and prognosis in subgroups with different clinical features of endometrial cancer. (a-o) GGH expression was used to predict survival in subgroups with different clinical characteristics. (a) Clinical stage: Stage I, (b) Clinical stage: Stage II & Stage III & Stage IV, (c) Age:<=60, (d) Age:>60, (e) BMI:<=30, (f) BMI:>30, (g) Histological type: Endometrioid, (h) Histological type: Serous, (i) Histologic grade: Gl, (j) Histologic grade: G2, (k) Histologic grade: G3, (l) Tumor invasion (%) :>=50, (m) Tumor invasion (%) :<50, (n)Diabetes: Yes, (o) Diabetes: No. (JPG 699 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM9_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 9 Utility evaluation of nomogram. (a) ROC curve of residual tumor. (b) ROC curve of radiation therapy. (c) ROC curve of clinical stage. (d) ROC curves of nomogram (Residual tumor, radiation therapy, clinical stage and GGH expression). (e–f) DCA to assess the clinical utility of nomogram (1, 3 and 5 year). (JPG 410 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM10_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 10 Analysis of mutation data of GGH in UCEC. (a) Waterfall plot showing the data of the 30 most common mutated genes and mutations in GGH in UCEC. (b) Cohort summary map showing the distribution of variants according to mutation classification, type and SNV category. The bottom indicates the mutation load of each sample, the type of variant classification. The bar graph shows the top ten mutated genes. (c) Mutation types and structural domains of GGH. (d) 3D structure diagram of GGH. (JPG 370 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM11_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 11 WGCNA construction and biological function enrichment analysis. (a) Sample clustering analysis. (b-c) Network topology analysis for different soft threshold powers. (d) Gene dendrograms and module colors. (e) Correlation of 33 modules with different degrees of differentiation. (f) Scatter plot of the dark green module containing GGH. (g) Visual network diagram of the dark green module containing GGH. (h) GO analysis of GGH and its highly related genes. (i) Analysis of GGH and its highly related gene KEGG. (JPG 726 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM12_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 12 Relationship between GGH expression in different immune cell subpopulations and prognosis of patients with endometrial cancer. (a) Enriched CD8+ T-cells. (b) Decreased CD8+ T-cells. (c) Enriched CD4+ memory T-cells. (d) Decreased CD4+ memory T-cells. (e) Enriched Regulatory T-cells. (f) Decreased Regulatory T-cells. (g) Enriched Regulatory T-cells. (h) Enriched Natural killer T-cells. (i) Enriched B-cells. (j) Decreased B-cells. (k) Enriched Basophils. (l) Decreased Basophils. (m)Enriched Eosinophils. (n)Decreased Eosinophils. (o) Enriched Macrophages. (p)Decreased Macrophages. (q) Enriched Type 1 T-helper cells. (r) Decreased Type 1 T-helper cells. (s) Enriched Type 2 T-helper cells. (t) Decreased Type 2 T-helper cells. (JPG 621 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM13_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 13 GEO database to validate the correlation between GGH and immune infiltration. (a) PCA analysis of the GSE17025 versus GSE106191 datasets before batch effect correction. (b) PCA analysis of GSE17025 versus GSE106191 dataset after batch effect correction. (c-j) Correlation of GGH expression with immune infiltration (MCPcounter algorithm). (c) T cells, (d) CD8+T cells, (e) Cytotoxic lymphocytes, (f) NK cells, (j) Myeloid dendritic cells, (h) Neutrophils, (i) B lineage, (j) Endothelial cells. (k) Correlation of GGH expression with immunostimulating factors. (l) Correlation of GGH expression with immunosuppressive factors. (JPG 683 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM14_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 14 Relationship between GGH expression and immune infiltration in pan-cancer. (a) Correlation of GGH expression with immune cell infiltration in pan-cancer (xCELL and EPIC algorithms). (b) Radar plot showing the relationship between GGH expression and MSI. (c) Radar plot showing the relationship between GGH expression and TMB. (d) Correlation between GGH expression and pan-cancer chemokines/receptors. (e) Correlation between GGH expression and pan-cancer MHC/Immunoinhibitor/Immunostimulator. (f) Correlation of GGH expression with TIDE score in pan-cancer. (JPG 1257 KB)

43032_2023_1363_MOESM15_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Figure 15 Correlation analysis of GGH with key genes in tumor-associated pathways. (a) G2M checkpoint, (b) Cellular response to hypoxia, (c) MYC targets, (d) P53 pathway, (e) Collagen formation, (f) EMT, (g) PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, (h) Proliferation, (i) TGFB, (j)DNA replication, (k) Inflammatory response, (l) ECM, (m) Angiogenesis, (n) DNA repair, (o) Degradation of ECM, (p) Genes up-regulated by reactive oxigen species (ROS). (JPG 1135 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, C., Du, Y., Huai, Q. et al. The Identification of Gamma-Glutamyl Hydrolase in Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma: a Predictive Model and Machine Learning. Reprod. Sci. 31, 532–549 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-023-01363-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-023-01363-0