Abstract

For the structural safety to counter the wind load, the roof shape and the roof slope both the constraints play an important role. The present study demonstrates the pressure distribution on the pyramidal roofs of a pentagonal and hexagonal plan low-rise single-story building due to the wind load through CFD simulation. This type of roofed building may be considered as one of the cyclone shelters as it is shown by post-disaster studies that pyramidal roof is found better than other roof shapes to resist the wind load. The modeling of the building and the meshing of the models have been carried out in ANSYS ICEM CFD, while the simulation process has been performed in ANSYS Fluent. To obtain the results, ANSYS CFD-Post has been utilized. For the simulation of the turbulent wind flow, a realizable k–ε turbulent model is used in the present study. In the current study, ten different building models (five with pentagonal plan and five with hexagonal plan) are generated having roof angles 20°, 25°, 30°, 35° and 40°, and all are simulated for 0°–45° wind direction @15° interval. The pressure coefficient contours for different wind directions for varying roof slopes are mapped in the present study. Results show that the hexagonal pyramidal roof surface building has low-pressure coefficients and better chances of survival than the pentagonal pyramidal roof surface building.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Different types of roofed buildings are widely used in coastal areas of India as well as all around the world. All these roofed buildings are exposed to the atmospheric wind and experience a significant wind load. As the wind has both advantageous and dangerous aspect, on the one hand it is beneficial as it has huge power potential [1,2,3] and helpful for ventilation [4] and on the other hand it loads the structures which come in its way. The past cyclone reports for Bhola Cyclone 1970, Bangladesh Cyclone 1991, Cyclone Nargis 2008, Hurricane Arthur 2014 and Cyclone Hudhud 2014 have shown a huge loss of lives and properties [5,6,7,8,9]. The wind-resistant structures can save lives and prevent property damage during cyclones, and the present study is an effort in the same direction. The key objectives of the present study are to investigate the variation of pressure coefficients on the pyramidal roof surface and to compare the same with the pressure coefficients on hip roof, as the hip roof is similar to pyramidal roof.

In oldfangled roofing arrangements, suctions due to high wind can cause key destruction, and it can cause subsequent intrusion of rain water and damage of inner elements [10]. So, the consideration of the wind load for the structural design along with other types of loads seems mandatory. The roof shape, roof slope and the wind direction play an important role in structural safety of buildings to counter the wind load [11, 12]. In a wind tunnel study, it was found that changes in the wind incidence angle may induce dissimilar pressures on different outside surfaces of a structure with the “+”-shaped plan [13].

The wind load investigation of building can be performed through wind tunnel testing or wall of wind study (WOW), but these experimental studies are time-consuming and expensive and require a lot of effort. Also the availability of experimental setup, i.e., wind tunnel and WOW, is very limited. So, to overcome all these limitations of experimental study, a substitute is required for the same. At present, CFD simulations or numerical analysis is good alternative to experimental study to govern the impact of wind load on structures [14,15,16,17].

In computational fluid dynamics, i.e., CFD, numerical analysis is utilized to find solutions to various problems involving fluid flows [18, 19]. CFD is a numerical analysis which can be used for both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) problems. Similar to CFD, there are other methods too for the numerical analysis of 2D, 3D and 4D problems such as hybrid orthonormal Bernstein, block-pulse functions wavelet method, time-fractional Benjamin–Ono (BO) equation, Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation and Haar wavelet method [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Thus, CFD may be defined as the use of applied mathematics, physics and computational software to evaluate the fluid flow behavior [26]. So, the present study is carried out by using numerical simulation.

In design and research, CFD decreases both cost and time and it delivers visualized and thorough information [27], and lots of wind load studies have been carried out by numbers of researchers using ANSYS Fluent [19, 28,29,30,31,32]. This software is novice-friendly while remaining highly accurate and quick [33]. Also, in the last five decades, CFD has evolved into an influential apparatus for the research work in structural aerodynamics [34]. As an alternative to wind tunnel experiments, a reasonable amount of research studies have been performed through CFD simulation, and CFD results have shown a good agreement with the experimental outcomes [35,36,37,38,39].

ANSYS CFD has a few number of methods or turbulent models for the simulation of geometric models such as SST model, k–ε model, LES model and k–ω model. And for the present study which is an atmospheric boundary-layer study, a realizable k–ε model has been used because of its suitability [40,41,42]. The past studies show the efficiency of the method.

When it comes to analytical study of wind load, there are wind codes too to get the wind pressure coefficients for various roof shapes directly. Different countries have their wind codes for evaluating wind loads such as Indian wind code IS 875 (Part 3), Australian and New Zealand wind code AS/NZS 1170.2:2011 [43], Japanese wind code AIJ Recommendations for Loads on Buildings, British wind code BS 6399-2: 1997 and American wind code ASCE/SEI 7-10 [44,45,46,47,48]. These code provisions include the pressure coefficients on gable roof, hip roof, multi-span gable roof, canopy roof, saw-tooth roof and mono-slope roof. None of the codes mentioned above has the information regarding pyramidal roofed buildings with varying heights.

This review of the literature shows that the maximum studies till date are related to low-rise buildings with gable roof, hip roof, multi-span gable roof, canopy roof, saw-tooth roof, mono-slope roof and dome-shaped roofs. So, the research work related to the pyramidal roofed buildings is very limited till the date.

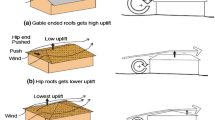

As past studies have been carried out on different type of roofs and wind standards of various nations includes the wind pressure coefficient values for different roof shapes except pyramidal roof as mentioned earlier. And few past studies show that pyramidal roof is better than the gable and hip roof and has the lowest uplift due to wind load. And that is why the pyramidal roof has more chances of survival during a cyclone, and the same is shown in Fig. 1 [11, 49].

Comparison between three different types of roofs for the over wind behavior [50]

As the similar studies on pyramidal roofed buildings have already been carried out in the past but in all those studies, the building models were with square or rectangular base, while in the present study the base has a shape of regular polygon. And by doing this, the effect of change in base shape has been investigated for pentagonal and hexagonal pyramidal roofed building models.

The pressure coefficient on both the pyramidal roofs from existing study has been compared with the pressure coefficient on hip roof from European Wind Standard and Indian Wind Standard, and both the pyramidal roofs are found better than hip roof again. So, the present study recommends the pyramidal roof for the construction in cyclone-prone regions. When it comes to wind pressure variation on pitched roofs, the roof slope play an important role, and the same may be noticed in wind standards of various countries. In the current study too, the suction decreases with the increase in roof slope.

Hence, in the present study, the influence of the roof slope on wind pressure distribution on roof surface of pyramidal roofed single-story buildings is examined thorough CFD simulation. In the existing study, the simulation is performed by using realizable k–ε turbulent model and the authentication has been carried out with earlier printed wind tunnel experimental data from the study carried out by David et al. [27].

Firstly, the wind tunnel experimental data used in the present study are described in Sect. 2. Then, the setting of computational domain, model dimensions, mesh type and mesh quality, boundary conditions and solver setting all are presented in Sect. 3. The outcomes which mainly include pressure coefficients and a comparison between pressure coefficients for different roof slopes are discussed in Sect. 4. Afterward, a comparison of pressure coefficient values with codal values is given in Sect. 5. And at the end of this manuscript, in Sect. 6 there is a conclusion for the existing study.

2 Wind tunnel experimental data used

David et al. [51] carried out wind tunnel experiments in an open-circuit ABL wind tunnel at IIT Roorkee, India. The ABL wind tunnel with a trial section of 15 m length has area of cross section 2.1 × 2.0 m2, and the wind velocity of 18 m/s can be attained. From this experimental study, the mean wind velocity and the turbulence intensity profile along wind direction has been utilized for the CFD simulation and validated.

With a power-law exponent (α = 0.14) for the velocity profile, the present study has 18% turbulence intensity along wind direction and 8 m/s mean velocity values at the model’s eave height (H). The linear length scale of turbulence (Lux) was obtained by computing the area under the autocorrelation curve of the oscillating velocity component, and Lux is nearly 0.45 m at a height H of 195 mm, which is almost 45 m as the corresponding full-scale Lux.

3 CFD simulation: setting of computational domain and criterion

The settings of computational domain and criterion for the present study are illustrated in this section. These criterion and settings have been utilized for the sensitivity evaluation (mesh resolution, turbulence model, inlet turbulent kinetic energy), which are given in Sect. 4.

3.1 Computational domain and meshing

A reduced scale (1:25) has been used in the present study for the construction of the computational domain as mentioned in Sect. 2. The building model is shown in Fig. 2a, b and computational domain is displayed in Fig. 2c as per the recommendations of Franke et al. [52] and Revuz et al. [31]. The dimensions of the domain are 2.725 × 5.225 × 1.5 m3 (W × L × H) which resemble 68.125 × 130.625 × 37.5 m3 in a full scale. The ultimate stretching ratio is used as 1.20 and the initial cell height is taken as 4.00 mm at the building wall. A grid sensitivity investigation is done based on three mesh types, i.e., coarse, elementary and fine grid, and the outcomes of the grid sensitivity investigation are incorporated. The elementary mesh is a suitable mesh for the present study shown in Fig. 3, and this grid is used in all the CFD simulations in the present study.

ANSYS ICEM CFD tool is used to produce advanced geometry and mesh of the model. An additional advantage of ICEM CFD is that it can create its own geometry or can import geometry via external CAD software. In this study, since our structural design was relatively simple, we have created geometry using ICEM CFD [53]. Two separate single-story building models with a pyramidal roof are generated in ICEM CFD. The base area of the building model is identical to the one in the study carried out at CBRI, Roorkee (India) [54]. The dimensions of the building models and domain geometry are shown in Fig. 2. Once the domain of the model is defined, the next step is to create the geometry of the building model within the domain in ICEM CFD.

For simulation work, it is necessary to distribute the whole domain volume into small cells also known as meshing. A hexahedral type of mesh is simple to generate and also gives good results. So, a structured hexahedral grid was used for meshing. The mesh was created with refined grid near the model as shown in Fig. 3 for getting more accurate results.

To get good results and a simpler simulation process, the mesh quality should be more than 0.5, which is considered as good. The mesh quality must be checked thoroughly for each and every model. The mesh quality for all the models was found above 0.6 in each case. On a scale of 0.0–1.0 in ICEM CFD, the mesh quality can be checked as shown in Fig. 3 (lower side). The bottom part of figure shows a bar chart for quality check. After the quality check, the mesh was converted into unstructured mesh, since the simulation is carried out using ANSYS Fluent in the current study, and it supports only unstructured mesh.

3.2 Boundary condition

For the demonstration of actual physical fluid flow, appropriate boundary conditions are necessary for the true simulation of the authentic flow. It is difficult all the time to state the detailed boundary setting at the inlet and outlet of the flow domain, which seem essential for an accurate solution. For the along-wind component of velocity with the subsequent expressions, a velocity inlet is used at the upwind boundary. The mean velocity, U, is similar to the velocity in wind tunnel study. In the ABL wind tunnel, the standard description of the velocity profile is given as follows:

The velocity profile and turbulence intensity profile are utilized from the wind tunnel experimental study by John et al. [55] performed at IIT Roorkee. With the help of experimental results, the validation of the numerical results is necessary, and for the same purpose, validation of both velocity profile and turbulence intensity profile is displayed in Fig. 4.

Experimental results a for velocity profile and b for turbulence intensity profile [55]

From Fig. 4, it can be seen that the wind tunnel velocity and the turbulence intensity profiles represent two different trend lines with equations y = 1.0559ln(x) + 4.7636 and y = 0.7554x − 0.297, respectively, and are used as user-defined function (UDF) at the inlet boundary to generate the boundary-layer flow throughout the domain. The computational domain’s top and the side walls are demonstrated as slip walls (nil normal wind velocity and nil normal gradients of entire variables). The static pressure is stated as zero at the outlet.

3.3 Solver settings

The principal equations and the related problem-specific boundary circumstances are solved through the finite volume method in Fluent. The basic principle behind the use of finite element method is that the model is subdivided into minor isolated parts which are called finite elements. The stiffness matrix size is determined by only the numeral of nodes and the outcomes are amended by increasing the nodes amount and collocation points [56]. The elements collectively make an overall matrix, and each element of the matrix has governed equations in Fluent.

As it is specified previously, the solutions are steady state, and the second-order differencing is used for the momentum, turbulence equations and pressure, and because of the robustness for steady-state and single-phase flow problems, the “coupled” pressure–velocity coupling method has been used. For the convergence state, the residuals must be fallen below the usually applied benchmarks of falling to 10−4 from their preliminary values afterward more than a few hundred iterations.

4 Outcomes and discussion

In the current study, pyramidal roofed structure models with pentagonal and hexagonal plan have been simulated through CFD by varying roof slopes. To determine the effect of roof slope on wind pressure distribution on roof surface is the key objective of the existing study. And this is carried out by plotting the wind pressure coefficient contours in ANSYS Fluent.

4.1 Contours of pressure coefficients

Contours of pressure coefficients of a pyramidal roof for various wind incidence angles were extracted using ANSYS Fluent and are shown in Fig. 5. The variation in magnitude of pressure coefficients has been indicated by a combination of colors. In the simulation process, the wind direction is taken along the X-axis.

In all the pressure coefficient contours, red color shows the highest positive pressure coefficients and the values lie between 0.54 and 0.57, while the highest negative pressure coefficient is shown by dark blue color and it lies between − 1.3 and − 2.0. Yellow color displays the contours of pressure coefficients lower than the highest positive pressure coefficient, and similarly, sky blue color represents the contours of pressure coefficients lower than highest negative pressure coefficient. And the values of pressure coefficients between the values shown by yellow and sky blue colors are represented by green color.

From pressure coefficients contours in Fig. 5, it can be observed that the negative pressure coefficient or suction increases with the increase in roof slope, while positive pressure coefficient has little fluctuation due to the change in roof slope for both the plan shapes. The highest suction was found near the ridge line (that separates windward face and leeward face) of the roof surface for all roof slopes.

As the roof slope increases, the region of roof surface where wind strikes directly also increases, and this results in larger positive pressure region. The same thing happens with the negative pressure coefficient, and the value increases with the increase in roof slope.

Figure 6 shows a comparison between maximum pressure coefficients for various roof slopes (θ) for varying wind directions (α). Figure 6a, b shows a different pattern for positive pressure coefficients for both pentagonal and hexagonal roof surfaces, while there is almost the same pattern for negative pressure coefficients for both the plan shapes as shown in Fig. 6c, d.

The highest maximum positive pressure coefficient and negative pressure coefficient for the pentagonal roof surface are found for 20° roof slope for 30° wind angle and for 40° roof slope for 45° wind angle, respectively, while the lowest maximum positive pressure coefficient is found for 30° roof slope for 0° wind angle and the lowest maximum negative pressure coefficient (suction) is found for 20° roof slope for 15° wind angle.

In case of hexagonal roof surface, the highest maximum positive and negative pressure coefficient was found for 20° roof slope for 15° wind angle and for 40° roof slope for 0° wind angle, respectively. And the lowest maximum positive and negative pressure coefficient was found for 40° roof slope for 30° wind angle and for 20° roof slope for 0° wind angle, respectively.

5 Comparison with codal values

As the pressure coefficients for pyramidal roofs are not given in Indian standard for wind loads and in European standard, the pressure coefficients on pyramidal roof from this study are compared with the pressure coefficients on hip roof. The area-weighted average values are estimated (Table 1) from given values of pressure coefficients and other details of roof in both the wind standards [44, 57].

From Table 1, it is clear that pyramidal roofs with the pentagonal and hexagonal plan are better than hip roof. We can see that the numerical values computed for pyramidal roofs differ to varying extents from the standard values obtained from the Indian Standard IS875 (part 3) and European Standard EN1991 for hip roof [10, 26]. These differences are mostly due to the fact that there are no standard data about pyramidal roof structures. The magnitude of pressure coefficients decreases with increasing roof slope for pentagonal pyramidal roofed building, while in case of hexagonal pyramidal roof pressure coefficient values are almost same for all three roof slopes. It may be observed that the pentagonal pyramidal roof with a slope of 40° is optimal from a wind load point of view.

6 Conclusions

The existing study is carried out by considering dissimilar roof slopes with various wind incidence angles. The foremost findings of the study are listed as follows:

-

The highest maximum positive pressure coefficient and negative pressure coefficient for the pentagonal roof surface are found for 20° roof slope for 30° wind angle and for 40° roof slope for 45° wind angle, while the lowest maximum positive pressure coefficient and negative pressure coefficient are found for 30° roof slope for 0° wind angle and for 20° roof slope for 15° wind angle, respectively.

-

In case of hexagonal roof surface, the highest maximum positive and negative pressure coefficient is found for 20° roof slope for 15° wind angle and for 40° roof slope for 0° wind angle, respectively. And the lowest maximum positive and negative pressure coefficient is found for 40° roof slope for 30° wind angle and for 20° roof slope for 0° wind angle, respectively.

-

As the roof inclination is increasing, negative pressure coefficient or suction is also increasing, while positive pressure coefficient has little fluctuation for both the plan shape.

-

The highest suction is found near the ridge line (that separates windward face and leeward face) of the roof surface for all roof slopes.

-

For low roof slope, most of the roof surface has negative pressure or suction and a small section only experiences positive pressure. This is because these low slope angles resemble a flat roof. Thus, the suction would be the major pressure in this situation. However, with increasing roof slope, the surface area under negative pressure or suction decreases, while the roof surface area under positive pressure increases.

-

Overall, the highest maximum positive pressure coefficient was found for hexagonal roof surface with 20° roof slope for 15° wind angle with a magnitude of 0.584 and the highest maximum negative pressure coefficient was found for pentagonal roof surface with 40° roof slope for 45° wind angle with a magnitude of 2.235.

-

When a pyramidal roof is compared with hip roof (from wind standards), it may be observed that the pentagonal pyramidal roof with a slope of 40° is optimal from a wind load point of view.

In the present study, it was found that the hexagonal pyramidal roof surface building has low-pressure coefficients and better chances of survival than the pentagonal pyramidal roof surface building. This may be because the hexagonal plan shape roof has more faces than pentagonal roof surface, and this causes the better distribution of wind over the roof surface.

References

Adhikari B, Kaphle B, Adhikari N, Limbu S, Sunar A, Kumar R (2019) Analysis of cosmic ray, solar wind energies, components of Earth’ s magnetic field, and ionospheric total electron content during solar. SN Appl Sci 1:453

Owoicho M, Agba A, Terwase S, Isikwue BC (2019) Investigation of wind speed characteristics and its energy potential in Makurdi, north central, Nigeria. SN Appl Sci 1:1–6

Donk P, Van Uytven E, Willems P (2019) Statistical methodology for on-site wind resource and power potential assessment under current and future climate conditions: a case study of Suriname. SN Appl, Sci

Mojtaba S, Maryam T, Najafabadi K, Shahizare B (2019) Review of common fire ventilation methods and Computational Fluid Dynamics simulation of exhaust ventilation during a fire event in Velodrome as case study. SN Appl Sci 1:685

I. Wikimedia Foundation, Cyclone Nargis, Wikipedia (2008)

I. Wikimedia Foundation, Cyclone Hudhud, Wikipedia (2014)

I. Wikimedia Foundation, 1970 Bhola cyclone, Wikipedia (1970)

I. Wikimedia Foundation, 1991 Bangladesh cyclone, Wikipedia (1991)

I. Wikimedia Foundation, Hurricane Arthur, Wikipedia (2014)

Mintz B, Mirmiran A, Suksawang N, Gan Chowdhury A (2016) Full-scale testing of a precast concrete supertile roofing system for hurricane damage mitigation. J Archit Eng 22:1–12

Jagbir Singh AKR (2019) Wind pressure coefficients on pyramidal roof of square plan low rise double storey building article. J Comput Eng Phys Model 2:1–15

Singh J, Roy AK (2019) Effects of roof slope and wind direction on wind pressure distribution on the roof of a square plan pyramidal low-rise building using CFD simulation. Int J Adv Struct Eng 11:231–254

Chakraborty S, Dalui SK, Ahuja AK (2014) Experimental investigation of surface pressure on ‘+’ plan shape tall building. Jordan J Civ Eng 8:251–262

Roy AK, Aziz A, Singh J (2017) Wind effect on canopy roof of low rise buildings. In: International Conf. Emerg. Trends Eng. Innovations Tech Nol. Manag., vol 2, pp 365–371

Roy AK, Sharma A, Mohanty B, Singh J (2017) Wind load on high rise buildings with different configurations: a critical review. In: International Conf. Emerg. Trends Eng. Innovations Tech Nol. Manag., vol 2, pp 372–379

Roy AK, Singh J, Sharma SK, Verma SK (2018) Wind pressure variation on pyramidal roof of rectangular and pentagonal plan low rise building through CFD simulation. In: Int. Conf. Adv. Constr. Mater. Struct., pp 1–10

Roy AK, Khan MM (2016) CFD simulation of wind effects on industrial chimneys. In: Civ. Eng. Conf. Sustainable

Blocken B, Moonen P, Stathopoulos T, Carmeliet J (2008) Numerical study on the existence of the venturi effect in passages between perpendicular buildings. J. Eng. Mech. 134:1021–1028

Van Hooff T, Leite BCC, Blocken B (2015) CFD analysis of cross-ventilation of a generic isolated building with asymmetric opening positions: impact of roof angle and opening location. Build Environ 85:263–276

Ali MR (2019) A truncation method for solving the time-fractional Benjamin-Ono equation. J Appl Math 2019:1–7

Ali MR, Hadhoud AR, Srivastava HM (2019) Solution of fractional Volterra–Fredholm integro-differential equations under mixed boundary conditions by using the HOBW method. Adv Differ Equ 2019:1–14

Ma W-X, Ali MR (2019) New exact solutions of nonlinear (3 + 1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation. Adv Math Phys 2019:1–7

Ma W-X, Ali MR, Mousa MM (2019) Solution of nonlinear Volterra integral equations with weakly singular kernel by using the HOBW method. Adv Math Phys 2019:1–10

Ali MR, Baleanu D (2019) Haar wavelets scheme for solving the unsteady gas flow in four-dimensional. Therm Sci 2019:292–301

Ali MR, Hadhoud AR (2019) Hybrid Orthonormal Bernstein and Block-Pulse functions wavelet scheme for solving the 2D Bratu problem. Results Phys 12:525–530

Margaret Rouse (2014) Computational fluid dynamics, TechTarget - WhatIs.Com

T.D. Canonsburg (2013) ANSYS Fluent Tutorial Guide

Liu S, Pan W, Zhang H, Cheng X, Long Z, Chen Q (2017) CFD simulations of wind distribution in an urban community with a full-scale geometrical model. Build Environ 117:11–23

Bairagi AK, Dalui SK (2015) Optimization of interference effects on high-rise building for different wind angle using CFD simulation. Electron J Struct Eng 14:39–49

Lal S (2014) Experimental, CFD simulation and parametric studies on modified solar chimney for building ventilation. Appl Sol Energy 50:37–43

Revuz J, Hargreaves DM, Owen JS (2012) On the domain size for the steady-state CFD modelling of a tall building. Wind Struct 15:313–329

Verma SK, Roy AK, Lather S, Sood M (2015) CFD simulation for wind load on octagonal tall buildings. Int J Eng Trends Technol 24:211–216

Kuzmin D (2018) Computational fluid dynamics Wikipedia

Blocken B (2014) 50 years of Computational Wind Engineering: past, present and future. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 129:69–102

Blocken B, Carmeliet J, Stathopoulos T (2007) CFD evaluation of wind speed conditions in passages between parallel buildings—effect of wall-function roughness modifications for the atmospheric boundary layer flow. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 95:941–962

Ozmen Y, Aksu E (2017) Wind pressures on different roof shapes of a finite height circular cylinder. Wind Struct 24:25–41

Roy AK, Verma SK, Sood M (2014) ABL airflow through CFD simulation on tall building of square plan shape. In: Wind Eng., Patiala

Verma SK, Roy AK, Khan MM (2014) Wind tunnel modeling of wind flow around power station Chimney. In: 7th Natl. Conf. Wind Eng., Patiala, pp 185–194

Irungu P, Oboetswe M, Motsamai S, Ndeda R (2019) A comparative study of RANS—based turbulence models for an upscale wind turbine blade. SN Appl Sci 1:1–15

Hermann Knaus JB, Hofsäß M, Rautenberg A (2018) Application of different turbulence models simulating wind flow in complex terrain: a case study for the WindForS Test Site. Computation 6:1–25

Raviteja C, Rajkamal DVV (2016) Analysis of wind forces on a high-rise building by RANS-based turbulence models using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Int J Res IT Manag Eng 6:28–34

Pujowidodo H, Ramdlan GGG, Siswantara AI, Budiarso, Daryus A (2016) Turbulence model and validation of air flow in wind tunnel. Int J Technol 8:1362–1372

AS/NZS 1170.2:2011 (2016) Australian/New Zeeland Standard—Structural Design Action, Part 2: Wind Action, SAl Global Limited under licence from Standards Australia Limited, Sydney and by Standards New Zealand, Wellington

IS 875(Part 3): 2015 (2015) IS 875-3 Design loads (other than earthquake) for buildings and structures - code of practice.pdf, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi

ASCE Standard (2016) Wind loads: general requirements, wind loads on buildings, wind tunnel procedure (ASCE/SEI 7-16). In: Minim. Des. Loads Assoc. Criteria Build. Other Struct., pp 245–390

Architectural Institute of Japan (2015) Chapter 6 Wind loads. In: AIJ Recomm. Loads Build., Architectural Institute of Japan, Tokyo, pp 14–75

N.Z.S. and A. Standard (2011) Structural design actions—part 2: wind actions (AS/NZS 1170.2:2011)

B.S. Institution (1997) BS 6399-2: 1997 British Standard, Loading for buildings-Part 2: Code of practice for wind loads

Kumar D, Singh R, Keote SA (2015) Construction of low rise buildings in cyclone prone areas and modification of cyclone. J Energy Power Sources 2:247–252

Jafari SAH, Kosasih B (2014) Flow analysis of shrouded small wind turbine with a simple frustum diffuser with computational fluid dynamics simulations. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 125:102–110

John AD, Singla G, Shukla S, Dua R (2011) Interference effect on wind loads on gable roof building. Procedia Eng 14:1776–1783

Franke J, Hellsten A, Schlunzen KH, Carissimo B (2011) The COST 732 Best Practice Guideline for CFD simulation of flows in the urban environment: a summary. Int J Environ Pollut 44:419

W. Contributors, ICEM CFD, Wikibooks, Free Textb. Proj. 3477701 (2018)

Roy AK, Babu N, Bhargava PK (2012) Atmospheric boundary layer airflow through CFD simulation on pyramidal roof of square plan shape buildings. VI Natl. Conf. Wind Eng., pp 291–299

John AD, Gairola A, Mukherjee M (2009) Interference effect of boundary wall on wind loads. In: Am. Conf. Wind Eng., San Juan, Puerlo Rico

Naghian M, Lashkarbolok M, Jabbari E (2016) Numerical simulation of turbulent flows using a least squares based meshless method. Int J Civ Eng 15(1):77–87

E. Standard (2011) Eurocode 1: Actions on structures—Part 1-4: General actions—Wind actions. European Union

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my special thanks and gratitude to my institute NIT Hamirpur, HP, for providing resources as well as Ministry of Human Resource Development, India, for providing research assistantship.

Funding

For the present study the funding is provided by Ministry of Human Resource Developement (MHRD) India, in form of Ph.D. assistantship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, J., Roy, A.K. CFD simulation of the wind field around pyramidal roofed single-story buildings. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1425 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1476-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1476-2

Keywords

- Wind pressure

- Pyramidal roof

- Roof slope

- Computational fluid dynamics (CFD)

- Mean pressure coefficients

- Velocity streamlines