Abstract

The article presents the concept of postdigital collective memory—a proposal that opens possible research fields for postdigital science and education. Postdigital collective memory is co-created between human and nonhuman beings and technological media, with the latter treated as sensitive sensors. In order to exemplify this concept, the article presents research results from field practices and design workshops conducted by the Humanities/Art/Technology Research Center at Lake Elsensee-Rusałka in Poznań and the prototype of the Sensitive Data Lake (SDL)—a digital environment project incorporating human and nonhuman actants and attempting to restore a shared narrative about a place whose history has been suppressed and has faded from public memory. This lake is one of many examples of what Tony Fry calls ‘total design’: it was created during World War II, through the forced labor of Jewish prisoners, as part of the Nazi expansion into the East; and the project attempted to redesign the environment and remove the local inhabitants. Following the theories that analyze the long duration of ‘total design’ (Fry) and the concepts of transitions design (Escobar), the author’s own Critical Media Design (CMD) method was applied to develop various experimental strategies for design and educational work related to the history and memory of the Elsensee-Rusałka site in the postdigital reality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The article introduces the concept of postdigital collective memory as design practices for a new approach to the remembrance of an environment affected by violence. It is situated within the postdigital paradigm, with its critical reflection on technology and design (Jandrić 2019b; Peters 2015), research on historical archives, and the posthumanist approach, which offers the possibility of organizing narratives as a co-creation of human and nonhuman beings (Haraway 2008; Tsing 2015). Designing practices and methods in this approach are closely related to critical thinking about historical forms of design in their local and translocal dimensions. The text tries to indicate how, using empirically grounded practices, it becomes possible to design the understanding of the complex structures of the past as part of activities based on collaboration and participation (Lindström et al. 2021). In this way, design practices serve as, on the one hand, a communal and social tool for conducting responsible criticism, and on the other hand, they participate in creating mechanisms for sharing memory in postdigital futures.

The first part presents the research results from field practices and design workshops conducted by the Humanities/Art/Technology Research Center at Lake Elsensee-Rusałka in Poznań. The aim of these workshops was to develop design practices for a place affected by violence, where the memory of that violence has faded, is repressed, or lacks a way to manifest itself in that location. In order to understand the ways in which this place functions within the structure of the modern city, the second part of the text reconstructs the history of its emergence. The lake was created during World War II through the forced labor of Jewish prisoners, as part of the Nazi expansion into the East. This colonization project attempted to redesign the environment and remove the local inhabitants. Elsensee-Rusałka is one of many examples of the violent practices of designing cities, landscapes, and infrastructures that Tony Fry calls ‘total design’ (Fry 2015, 2020). Thus, the case of Elsensee-Rusałka is situated in this text in a broader perspective of Nazi design strategies that were tied up with the expansion and subjugation of people, territories, and landscapes. At the same time, however, by focusing on this specific location, the text provides an opportunity to investigate the set of problems that this place and its functionality currently generate for the inhabitants of Poznań in the context of social memory.

Following the theories that analyze the long duration of ‘total design’ (Fry 2020) and the collaborative concepts of designing (Escobar 2018), the Critical Media Design (CMD) method (Jelewska and Krawczak 2022; Krawczak 2022) was applied to develop various experimental strategies for designing practices and educational work related to the history and lack of its memory at the Elsensee-Rusałka site. The presented workshop methods serve as a basis for proposing a project of a digital environment that aims to demonstrate the possibilities of creating narratives about the memory of this place.

Hence, the third part of the text presents the prototype of the Sensitive Data Lake (SDL)—a digital environment project involving human and nonhuman actants and attempting to restore a shared narrative about the history and contemporary aspects of site. The prototype simultaneously becomes a model that allows us to examine the shaping of postdigital collective memory, in which technology serves as a sensitive medium connecting human and nonhuman beings in the narratives focused on this place. It also reveals the mechanisms of memory operation and formation in the postdigital reality. As ‘memory is never just a servant of the past, a given. … It is a key to liberation from forms of oppression lodged in, and continued from, the past. Likewise, forgetting is not overcoming what has passed: the future, directional choice, demands remembrance.’ (Fry 2015:12).

Postdigital collective memory and the Sensitive Data Lake—the system designed for narrating the history of this lake—also become a design tool for transforming the elements of total design already present here, without physically interfering with the space, without erecting monuments or other forms of commemorating the past.

The Long Duration of the Total Design

In his essay, 'Whither Design/Whether History', the design theorist and philosopher Tony Fry analyzes aspects and historical manifestations of a concept he refers to as ‘total design’. He traces the direct origins of this practice back to the totalitarian regimes that emerged in the first half of the twentieth century (Fry 2015: 104). According to him, however, in order to understand the ways in which total design imposes functionalities on societies, it is worth seeing it in terms of long-term processes.

With the onset of the twentieth century, total design became a crucial component of the following developments: technologically advanced military projects that facilitated combined offensive warfare, the mass production of goods, and extremely intensive urban development. However, it was precisely war conditions and the military needs associated with conquest and destruction (during both World Wars in particular) that generated the numerous ideological assumptions associated with systemic design. Many of these concepts endure to this day, determining—often implicitly or in a deliberately concealed manner—certain socio-economic-political relations. Total design, with its military provenance, is therefore a strategy aimed not only at restructuring or redesigning not only specific places, buildings, or objects but also at introducing profound social changes and reconfiguring epistemic modes, values, and cultural practices (Fry 2009, 2015). In the broader sense, total design is also characterized by a deeply violent and anthropocentric perspective (Fry 2009), in which the ideology of one country and nation seeks to subdue others—through changing living spaces, transforming the territory and environment, and taking them over for their own needs, and by means of these actions, to establish new hierarchies of power and subjugation. It, therefore, has a colonial and racist dimension at its roots (Mbembe 2021; Tunstall 2023). From this perspective, total design is at the core of the onto-epistemic development of European modernity and its colonial drive, which unfolded over the course of hundreds of years (Fry 2015; Mbembe 2019; Woodham 1995; Mrozowski 1999; Mignolo 2011; Tunstall 2013). Later, total design became a key component of the continuation of this expansion—within the framework of accelerated techno-modernity (Fry and Tlostanova 2021). Fry also draws attention to the process of the successive development of total design elements in the contemporary capitalist doctrine, where design functions as an integral part of the processes of social engineering, algorithmization, and individuation (Fry 2015; Harrison et al. 2011).

Total design has taken various forms throughout history, from colonial and plantation systems, through totalitarian policies in which every aspect of people’s lives and the environment was subordinated to certain overarching goals, all the way to more limited forms of design, such as the development of highway networks in American cities in the 1950s, which transformed neighborhoods and ghettoized them, or geo-engineering projects that deformed the environment of the indigenous inhabitants of given areas in order to subordinate them to exploitation and extraction. Today, we can find elements of total design in many urban and landscape functions. Therefore, there is a constant and pressing need to develop situated practices that can critically engage with these projects while also revealing their history and the strategies embedded within them. Such an example of the element of Nazi total design is Elseensee-Rusałka.

Designing as a Process of Activating Knowledge

Although total design is usually depicted as a manifestation and execution of the programmatic coherence of the imposed aesthetic-political regime (visualized in entire systems, and structures), ultimately, as Fry demonstrates, it can only be presented and analyzed in a fragmentary form, wherein the intersections of places, objects, or images can be observed (Fry 2020: 124–125). Therefore, investigating and analyzing particular situations, events, objects, or structures can reveal the interacting determinants of real forces of pressure and violence operating behind this design. It is also important to take into consideration the fact that design is always a process (Escobar 2018, 2021) and an event (Fry 2017: 35–49). It constitutes an accumulating, dynamic, and open system of relationships that includes people, histories, spaces, practices, economies, and politics. Therefore, it is worth focusing on smaller elements, situations, and places and trying to find new ways to work with them in order to reveal the long-term strategies of the total design ideology. And as Clive Dilnot argues, comprehension is essential to this process (Dilnot 2020). As Arturo Escobar advocates, it must be a practice in action, a critical design that regains an understanding of complex and layered problems over the years (Escobar 2018, 2021). ‘What we lack is active knowledge’, Dilnot points out, adding:

‘comprehension’ is a key term here. It does not mean merely passive understanding … To comprehend sense is therefore to seek to face, but also to seek to face down, without evasion, what unavoidably and unprecedently is in its dimensions of implication and consequence. (Dilnot 2020: XIII)

On the other hand, Fry emphasizes the importance of prototyping and experimental implementation for critical practices:

we have very little comprehension of the complexity, on-going consequences, and transformative nature of our impacts; we do not understand how the values, knowledges, worlds and things we create go on designing after we have designed and made them. (Fry 2020:10)

Referring to the aspects outlined above, Arturo Escobar proposes a critical and collaborative mode of thinking implemented in practical designing solutions as a remedy for total and oppressive forms of design and planning. As he writes, designing is about ‘actively engaged participation in world-making … and needs to be brought to the fore again and widely discussed’ (Escobar 2021: 171). This conception of design Escobar calls—following Terry Irwin (Irwin et al. 2015), Cameron Tonkinwise (2015), and Ezio Manzini (2015)—‘transitions design’ (Escobar 2004, 2015, 2018: 144–151). It is based on taking an active part in dealing with political, economic, social, and ecological issues. Design in this sense is therefore not only the creation of new forms and objects, but it also becomes an important tool for thinking and conceptualizing the problem as the need to produce active and engaged knowledge.

The practices that we use in our research and educational work in workshops can also be situated with the perspective outlined by Escobar. The method we developed at the Humanities/Art/Technology Research Center is called Critical Media Design (CMD) (Krawczak 2022; Jelewska and Krawczak 2021, 2022). It stems from the conviction that we function in a technoculture, in which digital media co-create social epistemic apparatuses that shape not only knowledge of the present but also influence the memory of the past. We therefore ground our thinking about critical design in the postdigital paradigm. This allows us to treat digital media as objects of design rather than simply as tools. And moreover, by acting in this way, we can analyze more closely the postdigital (analogue–digital, material-media) nature of cognitive processes (Williamson 2018; Jandrić 2019a; Peters et al. 2021, 2023; Means et al. 2022).

Since we started our research in 2017, we have conducted five workshops on the Elsensee-Rusałka lake for interdisciplinary groups consisting mostly of designers, young researchers, artists, activists, and officials responsible for urban policies.Footnote 1 During these sessions, we used the CMD methods (Krawczak 2022) within the framework of the postdigital ecopedagogies (Jandrić and Ford 2022). As Jandrić and Ford put it: ecopedagogies are not just educational forms of learning but a new mode of critical thinking and practicing focused on understanding ‘ecosystems of humans, postdigital machines, nonhuman animals, minerals, objects, and more; ecosystems that are overdetermined by new forms of ontological hierarchies and capitalism, imperialism, and settler-colonialism’ (Jandrić and Ford 2022: 1). Of particular importance is the speculative approach to design and research in the field (Meskus and Tikka 2022; Dunne and Raby 2013; Johannessen et al. 2019), taking into account human-nonhuman relations, on the basis of which a critical analysis of the actants’ relationships in space is possible (Tsing 2015; Haraway 2008, 2016; Escobar 2021). The vast majority of our analytical methods, cooperation principles, data collection, and discussion were created and conducted specifically for researching this particular space. And each of the workshops in this place had a slightly different character, with the format and course depending on the people who formed the group with whom we were working at the time. Depending on the participants’ competencies and research questions, we focused on slightly different issues.

All of these collaborative work experiences allowed us to develop a prototype of the Sensitive Data Lake system, which aims to restore memory to this place as a form of postdigital narrative that is transformative and co-created between human and nonhuman beings.

Elsensee-Rusałka—Archival History

Each workshop began with a walk around the lake, combined with deep listening techniques (Oliveros 2005, 2022), followed by archival work, which involved analyzing the history of this place and its contexts. Elsensee-Rusałka is an artificial lake that was dug as part of the forced labor of Jewish prisoners during World War II (at that time under the name Lake Elsensee). The lake is one of many examples of the Nazi geopolitical modernization project, guided by the ideology of total design. Its history starts in the spring of 1941, when work began on digging in the mud and manually excavating the entire reservoir. For this purpose, about 11,000 people of mainly Jewish origin were resettled in Poznań and incarcerated in 29 forced labor camps located within the then-limits of Poznań. The lake’s construction involved reinforcing the bottom and banks with tombstones, mainly taken from nearby Jewish cemeteries, which were completely destroyed. This action was also aimed at exterminating the memory of Jewish culture in the area and erasing all of its traces.

The conditions in the labor camps and during the forced labor were dire (Matusik 2021). Executions were commonplace. The atrocious hygiene, diseases, especially typhus, and the debilitating work, combined with hunger, meant that death was part of the day-to-day reality for the prisoners. The forced labor camps in Poznań were liquidated in August–October 1943. The surviving prisoners who had endured the horrors of the labor camps and forced labor were transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp (Matusik 2021).

This is the archival history of the Elsensee. However, first, it must be seen in the wider perspective of the Nazi total design ideology, which aimed to recreate the German landscape in the conquered parts of Europe. Second, it should be noted that this history exists mainly in the archives of Poznań or Berlin and in the scholarly dissertations written by historians (Matusik 2021; Praczyk and Tereszewki 2020; Witkowski 2012; Grzeszczuk-Brendel 2021; Fabiszak and Brzezińska 2018). However, it has not become fully incorporated into the socially shared memory and stories about Poznań. It can be said that this history of the total design is forgotten and is sometimes recalled in completely different historical realities and contexts.

Green Total Design

In the Nazi project of expansion, colonialism, and exploitation, design played a crucial role, and there were several important issues at stake. It was used as ‘a designed organizational and management system; as a design system of mass production (of death, supported by specifically designed technologies); and as a designed architectural project’ (Fry 2015: 79). In this article, I focus on the latter aspect, narrowing it down to the design of landscape architecture.

For the Nazis, the physical conquest of the enemy, their destruction, or the takeover of territories were not the only things that mattered—the complete redesign of the place was also necessary. They used the term Neugestaltung (redesign) (Grzesczuk-Brendel 2021: 612; Brüggemeier et al. 2005), ‘the aim of which was to create effective forms of colonization by designing a landscape (Kulturlandschaft) that was made familiar for the settlers’ (Gröning and Wolschke-Bulman 2021). Neugestaltung thus involved moving the colonizer’s landscape into the colonized area and creating suitable conditions for sustainable settlement (Giaccaria and Minca 2016). The functions of these areas were supported the modernist cult of the strong and healthy body (Brüggemeier et al. 2005) and established their own hierarchies of species (human and nonhuman) (Jelewska and Krawczak 2022). As Peter Fritzsche writes in the book Life and Death in Third Reich, the Nazis intended to violently remake ‘lands and peoples’ into ‘spaces and races’ (Fritzsche 2008: 220). Geopolitical and racist expansion into the Eastern territories was developed and described by the Nazis as part of the so-called Generalplan Ost. It had various dimensions, but was primarily focused on gradually clearing the areas of their indigenous population in order to restore the 'original' nature. ‘With the Nazis’ triumph in 1933, volk, racism, and nature conservation were integrally linked’ (Brüggemeier et al. 2005: 6; Gröning and Wolschke-Bulman 2021). This was thus a form of expansion of biopolitical and racist ideology, which also involved the transfer of plant and animal species considered to be inherently German. An important element of this vision was also the concept of Lebensraum—a term that the geographer Friedrich Ratzel borrowed from nineteenth-century ecological theories—which was also a key conceptual element of the project of re-urbanization and revitalization of cities.

One of the main architects and planners involved in landscaping as a tool of ethnic cleansing was Heinrich Friedrich Wiepking-Jurgensmann, chair of the Institute of the Landscape Design of the University of Berlin. In late 1939, shortly after the invasion of Poland, he published an article in the journal Die Gartenkunst, entitled 'Der Deutsche Osten. Eine vordringliche Aufgabe für unsere Studierenden' ('The German East: A Priority Task for our Students'), in which he predicted a golden age for the German landscape and garden design that would surpass everything that even the most enthusiastic had previously dreamed of (Wiepking-Jürgensmann 1939; Gröning and Wolschke-Bulman 2021). Wiepking-Jurgensmann also puts forward plans for redesigning the conquered territories, including Poznań (German. Posen). The city was at the center of the so-called Warthenland, an area that was intended to be an integral part of the Third Reich and to be inhabited exclusively by Germans. Throughout the Nazi expansion project, the Warthenland was to be a paradise for fascist landscape planners, who could implement and experiment with new forms of urban landscaping based on the principles of Stadtlandschaft (city landscape) (Grzeszczuk-Brendel 2021: 614; Brüggemeier et al. 2005: 5). Therefore, analyzing the architecture and green planning of this city allows for a detailed tracking of the development and implementation of total design.

Lake Elsensee was a space that was supposed to fulfill the function of a location that would realize the ideal of the model Aryan citizen. It was one of the key elements of the extensive recreational system that was supposed to characterize the city as a whole. Wiepking-Jürgensmann designed a green axis oriented from east to west across Poznań, based on a system of watercourses and supplemented by artificial water reservoirs. He also planned urban recreational and sports areas and green sections separating numerous residential estates on the outskirts of Poznań (Grzeszczuk-Brendel 2021: 614).

The cult of a healthy lifestyle, and contact with ideologized and redesigned nature, was meant to contribute to the rapid development of a strong and expansive society and encourage Germans to settle in these areas in large numbers. In this aspect of planning, not only spatial relations between green and built-up areas were subject to planning; so too were citizens’ modes of behavior in these new spaces. The essence of these projects was ocularcentrism and the idea of designing was subordinated to thinking about shaping an attractive landscape. In this sense, this project almost perfectly fulfilled the basic ideological assumptions of total design, including the fact that it represented an abstract vision of a beautiful artificial landscape. As a product of total design, Elsensee was thus a visualization of ‘an ocularcentric force that strove to mobilize, via an aesthetic determinism’ (Fry 2020: 125).

The Long Duration of Total Design: Elsensee Becomes Rusałka

In the post-war years, after the communist regime took power, all the functions of the lake were preserved. The authorities did not carry out any denazification in terms of spatial planning and development; they only changed the name in the mid-1970s from Elsensee to Rusałka. From the perspective of Slavic culture and mythology, the name Rusałka in the context of the lake’s origin is somewhat peculiar. In mythological tales, Rusałka is a water nymph, a spirit who dies violently and before her time, such as young women who commit suicide because they have been jilted by their lovers (Zelenin 1927). Coming from the afterlife, driven by revenge, she seduces young boys and kills them, dragging them into the lake. The implicit hauntological and necrological narrative is intensified by the fact that there are two monuments—places of remembrance—located by the lake, in places where the Nazis executed over 2000 people in 1940. They were mainly Poles from the first concentration camp in the area, called Fort VII, located less than 2 km from the lake.

In the first decades after World War II, the recreational functions of the lake were expanded, with the completion of beaches and a sports center. The period from the 1960s to the 1980s was a time of extraordinary popularity for this place. Later, due to a lack of investment in recreational infrastructure, Poznań’s residents began to lose interest in the lake and its environs. This situation was particularly noticeable in the 1990s, after the political transformation. However, in recent years, the lake area has been intensively developed. Not only have the recreational functions been restored, but the sports infrastructure has been expanded, and an ecological education program has been established. A walking trail around the lake has been equipped with informational signs and directions, and even a waterbird observatory has been built.

The lake has been rather informally divided into two culturally distinct shores, even though both are subject to the same cultural policy. The northern shore serves an official function and has been strongly adapted to meet recreational needs, with a sandy beach, a restaurant, and a facility for water equipment rental (see Fig. 1). The southern shore appears to be subject to a different policy, with no tourist infrastructure other than walking paths, benches, and bike racks. This shore is located in close proximity to the site where Polish prisoners from a concentration camp were shot, and occasionally—when, as a result of a dry summer, the level of the water in the lake falls—the tombstones from Jewish cemeteries that the Nazis used to reinforce the lake bottom and shoreline become visible (see Fig. 2). This shore is also home to the 'wild beach'. This part is much less attractive, due to greater noise, as a railway line and a fast traffic route run nearby. Around the lake, a system of ecological education imposed by the city authorities is also being developed. It involves the somewhat arbitrary and schematic placement of signs informing about a few plant and animal species present in this area, which lacks depth and context, considering the nature of the place. This is exemplified by the signs informing about aquatic plants—such as curly pondweed (lat. Potamogeton crispus)—supplemented with the telling slogan: 'Beneficial for the environment, safe for people.'

The recreational infrastructure of Lake Rusałka (Visit Poland Online 2023)

Hence, this small body of water provides an illusory sense of contact with nature: it neutralizes and naturalizes its slave and necropolitical origins, embodies nature’s culturalization and commercialization, while at the same fostering a belief in ecological being (Jelewska and Krawczak 2021).

The Lake as a Place on the Internet

An integral part of our workshops was the close research into, and critical analysis of, the relationships produced by the politics of power structures in the contemporary approach to the history of the lake. One such power structure is the Rusałka project resulting from Google Maps, which we also investigated as a currently significant sphere of constructing the digital representation of place. The analysis of reactions from Google Maps users evaluating, commenting on, and reviewing Lake Rusałka shows primarily that it is considered to be 'an excellent place for relaxation and sports'. It should be emphasized that the number of comments, photos, and reactions left by users who evaluated the lake is significant when compared to other places with similar functions in the city. It was given a rating of 4.6 by users (based on 693 ratings and reviews, and 12 questions; as of 3 March 2023). A content analysis of all the reviews written by users shows that only 1.3% of the comments refer to the origin of the lake. Specifically, there are only eight comments and one question (left unanswered). Moreover, the content of these comments only refers directly to the use of forced labor of Jewish prisoners in one case. In other cases, only the fact that the lake was created as an artificial reservoir during World War II is mentioned. Identifying the structure of knowledge production about the Elsensee-Rusałka space on the Internet is important, because for many people the information contained on platforms such as Google Maps is the first source of information about the history of places and functionalizes their attitude to a particular urban space.

Therefore, one of the forms that our practices during workshops take was designing media diagrams, which allowed us to approach the problem of the displaced history of Elsensee.

Media diagrams assume the possibility of experimental use of any type of medium in their architecture, not limited only to the visual representation of the issue and information about it. The diagrams prepared by the participants took various forms, some used material objects found during field sessions (such as plant fragments, stones, garbage, and objects left or lost by users of the space), others were based on a hybrid architecture—combining personal notes and graphics with digital elements (like videos with interviews, gathered sounds of the lake environment, links to websites, and blogs with information about the lake), and still others took advantage of the possibility of precise contextualization of issues by creating very large mind maps open to the development of new entanglements. These kinds of diagrams can be situated in the postdigital paradigm, as a critique of solely using data from systems based on top-down designed GIS tools, such as the aforementioned Google Maps, and focus—as advocated by feminist geographers—‘on the construction of place through digital literary geographies, histories and memories …’ (Pavlovskaya 2016; Dear 2015; Cresswell et al. 2015).

The aim of creating media diagrams of the place was to identify the elements of space, objects, phenomena, human and nonhuman beings, etc., between which relationships of dependencies are built according to specific orders of analyses: ocular-centric, visual, and kinetic. Data obtained during fieldwork with media tools was also important, as they enabled experimental forms of slow observation (Tishman 2018) and deep listening. Since this is a place with a designed visuality, sound seemed to us a significant medium through which it can be experienced differently. During the listening sessions, it turned out that at certain times of the day this place is incredibly loud, while it becomes quieter at other times. The character of the soundscape in this location is also significantly influenced by the seasons and weather conditions.

To compare our sonic data, we examined the official acoustic maps of the city developed by the city authorities, which in reality are not based on collected data but on averaged forecasts of the type of noise emission that specific urban infrastructures generate.Footnote 2

Based on the analysis of the collected material (almost one hundred diagrams), recurring elements were identified. Some of the selected categories are internally complex (referring to a larger set of phenomena and problems), and some are also specifically dependent on the time and circumstances in which field research was conducted. The most frequently identified categories organizing the core of the diagrams were noise, waste, and disturbing functions of recreational infrastructure. So, they were not the same as those from Google Maps or digital travel platforms.

Speculative media diagrams were used to distort the envisioned “perfect recreation place” created by city guides and Google Maps. They also helped identify locations that hold historical and contemporary significance, allowing us to pinpoint significant spots around the lake for storytelling in the Sensitive Data Lake prototype.

Sensitive Data Lake (SDL): The Concept

The conducted research and analysis of various media materials collaboratively produced during workshops, which we tested in the lake area, led us to search for the possibility of creating a postdigital project that would enable the recovery of the lake space for collective shared social memory (Halbwachs 1992; Barash 2020; Anastasio 2012). In the process of designing an environment entitled Sensitive Data Lake, we are using the architecture of a data repository named as ‘data lake’ (Singh 2019) and the concept of ‘alien AI’ based on nonhuman consciousness (Shanahan 2016; Sloman 1984).

We use the term 'data lake' in two senses. Firstly, it refers to a repository format that allows storing various types of data in a non-hierarchical architecture. In this system, different types of files can be stored without the need for organizing, sorting, and categorizing them. As a result, large collections of diverse data can be used for machine learning development without prior limitation as to data types. In the environment we are designing, this enables the construction of open, complex narratives. Secondly, the data lake serves as a functional metaphor, allowing us to perceive the lake as an already existing living archive or 'ready-made archive' that aggregates data and memory forms from human and nonhuman beings. This type of approach, dealing with physical places as archives, is also an important concept of contemporary research practices implemented as part of the environmental history methodology (Turkel 2006).

In designing the system’s operational functions, we are using the concept of nonhuman AI described in the text The structure of the space of possible minds by Aaron Sloman (1984) and later extended as ‘alien AI’ by Murray Shanahan (2016). Working with potential other forms of intelligence, other cognition and perception, as Aaron Sloman writes, must be based on ‘performing inferences, including not only logical deductions but also reasoning under conditions of uncertainty, including reasoning with non-logical representations, e.g., maps, diagrams, models’ (Sloman 1984: 41). Following the concept of Sloman, Murray Shanahan suggests that this kind of approach to designing AI could be based on different forms of nonhuman consciousness, embedded, among other things, in ‘conscious exotica’ cognition radically different from ours (Shanahan calls them forms of complex alien consciousness) (Shanahan 2016). It is seeking new forms of design beyond purely human cognitive modes. In addition, the use of unstructured and non-hierarchical data repositories, such as the data lake in our project, opens up possibilities for working with large numbers of diverse media objects.

These recognitions about the technological side of the SDL project resonate with the concept of friction, established in ethnographic research by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, and can be described in SDL as an attempt to create ‘zones of cultural friction’ that ‘arise out of encounters and interactions’ (Tsing 2005: xi). As Tsing puts it, frictions are ‘the awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interconnection across difference’ (Tsing 2005: 4) and, therefore, can serve ‘as a reminder of the importance of interaction in defining movement, cultural form, and agency,’ (…) and inflection of ‘historical trajectories, enabling, excluding, and particularizing’ (Tsing 2005: 6). Table 1 presents some possible stories for the SDL project.

Sensitive Data Lake: The Prototype

The Sensitive Data Lake prototype is the result of considering the lake space as a 'ready-made archive'—one that only requires finding methods and tools to initiate a collective work on understanding the many years of traces that have accumulated in this place.

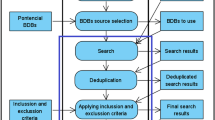

What is important in our concept is that the functionality of the code and the utilization of the gathered digital data can only be accessed within the physical space of the lake. In other words, participants must be present in situ to 'connect' to the data lake. Additionally, the responsive structures and behaviors of the designed system will be negotiated between human and nonhuman beings inhabiting the lake ecosystem. The nonhuman activity will be represented through data collected by several measuring stations, which will analyze factors such as atmospheric conditions, temperature, air, and water pollution levels, noise, water oxygenation, and soil humidity (see Diagram 1). The decision-making power of the entire system will be interdependent with alien AI. The design basis of this prototype is the idea of creating a space for shared postdigital memory, where memory elements are spread in physical and technological artifacts and shared by human and nonhuman beings. SDL thus enables new forms of experiencing the physical space of the lake and forming a postdigital memory of the history and present of the place.

The prototype does not alter the recreational function of the space, nor does it introduce visible architectural or visual interventions into the environment. The interaction of participants with the SDL may go unnoticed by other 'unconnected' individuals present in the lake area. The experience of connected participants will rely solely on auditory interaction, using smartphones with the SDL application installed and connected headphones. In this way, the individuals 'connected' to the SDL will not be distinguishable from other space users, such as walkers, beachgoers, joggers, or cyclists. The available narratives, soundscapes, and stories will depend on the precise location of participants around the lake (GPS tracking), their behavior analyzed based on movement data within the lake area (geostamp), as well as the specific date, time, and season (timestamp). Over time, these collected metadata will form 'behavioral patterns' that, in relation to environmental measurement data, can serve as a basis for developing interaction forms.

The soundscapes that participants will be able to hear will depend on environmental data, and the stories will have many variants, intertwining with other layers of sound. This process will be dependent on the location, interaction with other participants, current environmental data, and decisions made by alien AI. Thus, the structure of interaction with the data lake will reflect the mechanisms of memory, which are often devoid of rational rigor and are susceptible to sensory and kinetic stimuli, as well as mutual interactions among different levels and layers of shallow and deep memory.

Soundscapes and stories may undergo not only changes and distortions but also mutations introduced by alien AI. For example, in situations of anomalies related to significant deviations from ecological norms due to pollution or extreme weather conditions, more unpredictable changes may occur in the sound and narrative layers.

The strategy designed within SDL can be also perceived as a form of postdigital pedagogy. It goes beyond social educational functions and focuses on sharing memory about a place seen as a living phenomenon that must be constantly evoked, recreated, and prevented from becoming solely a historical sediment. The unpredictability and difficult-to-define course of narrative emergence involves shared and dynamic awareness of history, transformations, and the endurance of deep structures of total design in this place.

Conclusions: Postdigital Collective Memory

With regard to postdigital studies, the issue of postdigital collective memory could become a new research field, adding to, for example, the cognitive aspects of memory (Peters 2015) and the influence of digital media on its form (Neiger et al. 2011), biodigital philosophy (Peters et al. 2021), and critical theories related to existing media infrastructures (Parks and Starosielski 2015). Multimedia, multi-structural, indefinite storytelling becomes also a socially engaging mechanism here; participants can independently find themselves in multi-layered structures and establish relationships with various entities of the stories (see Jelewska and Krawczak 2022).

The SDL project described in this text is not only a prototype of an experimental environment that makes possible interactions with implicit structures of total design, but is also a tool for exploring possible spectral forms of memory in the postdigital paradigm. This is an open mechanism of transitions design (Escobar) in shaping postdigital collective memory where ‘unexpected alliances can arise’ (Tsing 2005:12). This memory takes shape between history, the weather, the environment, people, and past and present events, as a speculative narrative. The inclusion of AI as an actant co-generating friction is also another attempt to escape total design. As Sloman argued in the context of nonhuman AI, ‘by mapping the space of possible mental mechanisms we may achieve a deeper understanding of … how they fit into a larger realm of possibilities’ (Sloman 1984: 42).

The prototype that is being developed would not be possible without the entire workshop process, which combines archival research, field research, academic theories, and the search for new methods and counter-diagramming strategies suitable for such a complex space. The collectivity of this project is not exhausted in a closed data loop, as it is open to newcomers, as well as unexpected situations and environmental conditions that can co-create narratives associated with this place. Being aware that total design is systemic, ideological, and closed to randomness or errors, we have decided not only to open the archives of Elsensee-Rusałka but also to reveal the entanglement of the temporal and spatial aspects of this place. We do not propose erecting more monuments, cementing, or filling the lake to create a static place of memory. Instead, we intend to weave a media as sensitive tissue that will enable the complicated relations that shape and define this place to be co-experienced.

Notes

So far, we have conducted 5 workshops. Three were organized by municipal organizations in Poznań, and the remaining two were conducted by the Humanities/Art/Technology Research Center at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland as part of research carried out under the NPRH grant. All workshops had an open call, with an average of 20 to 25 participants. In the workshops sponsored by municipal organizations, approximately 70% of the participants were residents of Poznań and the surrounding areas. In the two workshops organized by the HAT Research Center, about 70% of the participants were from outside Poznań. The average age of the participants ranged from 24 to 40, mainly consisting of artists, activists, young researchers, and city officials. The workshops did not survey the participants’ gender or ethnic background. They lasted from 7 to 10 days. Three workshops took place during the summer months, when the lake area experiences high traffic and usage, while one occurred in spring and one in autumn, when it is less used.

References

Anastasio, T. J. (Ed.). (2012). Individual and Collective Memory Consolidation: Analogous Processes on Different Levels. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Barash, J. A. (2020). Collective Memory and the Historical Past. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Brüggemeier, F. J., Cioc, M., & Zeller, T. (Eds.). (2005). How Green Were the Nazis? Nature, Environment, and Nation in the Third Reich. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Cresswell, T., Dixon, D. P., Bol, P. K., & Entrikin, J. N. (2015). Editorial. GeoHumanities, 1(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2015.1074055.

Dear, M. (2015). Practicing Geohumanities. GeoHumanities, 1(1), 20-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2015.1068129.

Dilnot, C. (2020). Tony Fry’s Defuturing: A New Design Philosophy. In T. Fry, Defuturing: A New Design PhilosophyLondon: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Dunne, A., Raby F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA & London, UK: The MIT Press.

Escobar, A. (2004). Other Worlds Are (Already) Possible: Self-Organisation, Complexity, and Post-capitalist Cultures. In J. Sen, A. Anad, A. Escobar, & P. Waterman (Eds.), The World Social Forum: Challenging Empires (pp. 349–358). Delhi: Viveka.

Escobar, A. (2015). Transiciones : A Space for Research and Design for Transitions to the Pluriverse. Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2015.1085690.

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Escobar, A. (2021). Afterwards. In K. M. Murphy & E. Y. Wilf (Eds.), Designs and Anthropologies. Frictions and Affinities (pp. 169–191). Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press; Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Fabiszak, M., & Brzezińska, A. W. (2018). Cmentarz, Park, Podwórko: Poznańskie Przestrzenie Pamięci. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Fritzsche P. (2008). Life and Death in the Third Reich. Cambridge, MA & London, UK: The Belknap Press.

Fry, T. (2009). Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics, and New Practice. Oxford, UK & New York, NY: Berg.

Fry, T. (2015). Whither Design/Whether History. In T. Fry, C. Dilnot, & S. C. Stewart (Eds.), Design and the Question of History (pp. 1–111). London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Fry, T. (2017). Remaking Cities. An introduction to Urban Metrofitting. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Fry, T. (2020). Defuturing: A New Design Philosophy. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Fry, T., & Tlostanova, M. V. (2021). A New Political Imagination: Making the Case. London and New York: Routledge.

Giaccaria, P., & Minca, P. (Eds.). (2016). Hitler’s Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Gröning, G., & Wolschke-Bulman, J. (2021). The Concept of “Defense Landscape” (Wehrlandschaft) in National Socialist Landscape Planning. In A. Tchikine & J. D. Davis (Eds.), Military Landscapes (pp. 201–220). Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Grzeszczuk-Brendel, H. (2021). Heim and Heimat — Poznań during the Second World War as a Starting Point for Possible Paths of Interpretation. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung, 70(4), 609–627. https://doi.org/10.25627/202170411053.

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On Collective Memory. Trans. C. A. Lewis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2008). When Species Meet. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Harrison, S., Sengers, P., & Tatar, D. (2011). Making Epistemological Trouble: Third-Paradigm HCI as Successor Science. Interacting with Computers, 23(5), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2011.03.005.

Irwin, T., Kossoff, G., & Tonkinwise, C. (2015). Transition Design Provocation. Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2015.1085688.

Jandrić, P., & Ford, D. R. (Eds.). (2022). Postdigital Ecopedagogies: Genealogies, Contradictions, and Possible Futures. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97262-2.

Jandrić, P. (2019). The Postdigital Challenge of Critical Media Literacy. The International Journal of Critical Media Literacy, 1(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1163/25900110-00101002.

Jandrić, P. (2019). We-Think, We-Learn, We-Act: the Trialectic of Postdigital Collective Intelligence. Postdigital Science and Education, 1(2), 257-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00055-w.

Jelewska, A., & Krawczak M. (2021). Elsensee-Rusałka. Spektrokartografie środowiska. In B. Koncewicz & A. Mądry (Eds.), Podróżować, mieszkać, odejść… (pp. 217–238). Poznań: Poznańskie Studia Polonistyczne. https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/26789/1/Jelewska%2c%20Krawczak%2c%20Elsensee-Rusałka%20spektrokartografie%20środowiska.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Jelewska, A., & Krawczak M. (2022). Spectrograms of the environment: entangled human and nonhuman histories. In A. Pau, I. Vila, & S. Tesconi (Eds.), Possibles: Proceedings of 27 international Symposium on Electronic Art (pp. 376–382). https://doi.org/10.7238/ISEA2022.Proceedings.

Johannessen, L. K., Keitsch, M.M, Nilstad Pettersen I. (2019) Speculative and Critical Design — Features, Methods, and Practices. Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, 1(1), 1623 - 1632. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsi.2019.168.

Krawczak, M. (2022). Counter-Mapping with Sounds in the Practices of Postdigital Pedagogy. Postdigital Science and Education, 5(2), 386-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00333-0.

Lindström, K., Hillgren, P.-A., Light, A., Strange, M., & Jönsson, L. (2021). Collaboration. Collaborative future-making. In C. L. Galviz, E. Spiers, M. Büscher, & A. Nordin (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Social Futures: Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429440717.

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Matusik, P. (2021). Historia Poznania. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Miejskie Posnania, Fundacja Rozwoju Miasta Poznania, Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

Mbembe, A. (2019). Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Mbembe, A. (2021). Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization. New York: Columbia University Press.

Means, A., Jandrić, P., Sojot, A. N., Ford, D. R., Peters, M. A., & Hayes, S. (2022). The Postdigital-Biodigital Revolution. Postdigital Science and Education, 4(3), 1031-1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00338-9.

Meskus, M., & Tikka, E. (2022). Speculative Approaches in Social Science and Design Research: Methodological Implications of Working in ‘the Gap’ of Uncertainty. Qualitative Research, 146879412211298. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941221129808.

Mignolo, W. (2011). The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mrozowski, S. A. (1999). Colonization and the Commodification of Nature. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 3(3), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021957902956.

Neiger, M., Meyers, O., & Zandberg, E. (Eds.). (2011). On Media Memory. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230307070.

Oliveros, P. (2005). Deep Listening: A Composers’s Sound Practice. New York and Shanghai: iUniverse.

Oliveros, P. (2022). Quantum Listening. London: Ignota Books.

Parks, L., & Starosielski, N. (Eds.). (2015). Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Pavlovskaya, M. (2016). Digital Place-Making: Insights from Critical Cartography and GIS. In C. Travis & A. von Lünen (Eds.), The Digital Arts and Humanities (pp. 153–167). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40953-5_9.

Peters, M. A. (2015). Interview with Pierre A. Lévy, French Philosopher of Collective Intelligence. Open Review of Educational Research, 2(1), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2015.1084477.

Peters, M. A., Jandrić, P., & Hayes, S. (2021). Biodigital Philosophy, Technological Convergence, and New Knowledge Ecologies. Postdigital Science and Education, 3(2), 370-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00211-7.

Peters, M. A., Jandrić, P., & Hayes, S. (2023). Postdigital-Biodigital: An Emerging Configuration. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 55(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1867108.

Praczyk, M., & Tereszewski, M. (2020). Reading Monuments: A Comparative Study of Monuments in Poznań and Strasbourg from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Berlin and New York: Peter Lang.

Salata, S., Michlewicz, M., & Szwajkowski, P. (2015). Materiały do poznania myrmekofauny Polski. Wiadomości Entomologiczne, 34(4), 57–66.

Shanahan, M. (2016). Conscious Exotica. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/beyond-humans-what-other-kinds-of-minds-might-be-out-there. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Singh, A. (2019). Architecture of Data Lake. International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 411–414. https://doi.org/10.32628/CSEIT1952121.

Sloman, A. (1984). The structure of the space of possible minds. In S. Torrance (Ed.), The Mind and the Machine: philosophical aspects of Artificial Intelligence (pp. 35-42). Sydney: Halstead Press.

Tishman, S. (2018). Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning through Observation. New York, NY and Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Tonkinwise, C. (2015). Design for Transitions—from and to What? Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1), 85–92.

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tunstall, E. (2013). Decolonizing Design Innovation: Design Anthropology, Critical Anthropology, and Indigenous Knowledge. In W. Gunn, T. Otto, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

Tunstall, E. (2023). Decolonizing Design: A Cultural Justice Guidebook. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Turkel, W. J. (2006). Every Place Is an Archive: Environmental History and the Interpretation of Physical Evidence. Rethinking History, 10(2), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520600649507.

Visit Poland Online. (2023). Poznan. https://visitpoland.online/poznan/. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Wiepking-Jürgensmann, H. F. (1939). Der Deutsche Osten. Eine vordringliche Aufgabe für unsere Studierenden. Die Gartenkunst, 52, 193.

Williamson, B. (2018). Brain Data: Scanning, Scraping and Sculpting the Plastic Learning Brain Through Neurotechnology. Postdigital Science and Education, 1(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0008-5.

Witkowski, R. (2012). Juden in Posen: Führer zu Geschichte und Kulturdenkmälern. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Miejskie Posnania.

Woodham, J. M. (1995). Resisting Colonization: Design History Has Its Own Identity. Design Issues, 11(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511613.

Zelenin, D. (1927). Russische (Ostslavische) Volkskunde. Berlin and Leipzig: de Gruyter.

Funding

The article is the result of research carried out under the NPRH grant of the Ministry of Education and Science, entitled Mediated Environments. New practices in humanities and transdisciplinary research (no: 0014/NPRH4/H2b/83/2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The concept behind the article, the material preparation, the literature review, and analysis were entirely prepared by the author.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The article includes references to the workshops and Critical Media Design methods developed together with Michał Krawczak.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jelewska, A. Postdigital Collective Memory: Media Practices Against Total Design. Postdigit Sci Educ 6, 259–278 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-023-00421-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-023-00421-9