Key summary points

This clinical review summarizes the current evidence on the risks of antipsychotic-related falls in older adults, including aspects of pharmacokinetics and -dynamics to assist clinicians in (de)prescribing antipsychotics in older people.

AbstractSection FindingsAntipsychotics are widely used for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium and insomnia in older adults despite off-label indications. Antipsychotics increase the risk of falls due to anticholinergic and extrapyramidal effects, sedation, and cardio- and cerebrovascular adverse effects.

AbstractSection MessageConsider deprescribing of antipsychotics in older adults at risk of or with falls if there is no current indication, or if safer alternatives are available, or if antipsychotics are prescribed for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, insomnia, or delirium.

Abstract

Purpose

Because of the common and increasing use of antipsychotics in older adults, we aim to summarize the current knowledge on the causes of antipsychotic-related risk of falls in older adults. We also aim to provide information on the use of antipsychotics in dementia, delirium and insomnia, their adverse effects and an overview of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms associated with antipsychotic use and falls. Finally, we aim to provide information to clinicians for weighing the benefits and harms of (de)prescribing.

Methods

A literature search was executed in CINAHL, PubMed and Scopus in March 2022 to identify studies focusing on fall-related adverse effects of the antipsychotic use in older adults. We focused on the antipsychotic use for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, insomnia, and delirium.

Results

Antipsychotics increase the risk of falls through anticholinergic, orthostatic and extrapyramidal effects, sedation, and adverse effects on cardio- and cerebrovascular system. Practical resources and algorithms are available that guide and assist clinicians in deprescribing antipsychotics without current indication.

Conclusions

Deprescribing of antipsychotics should be considered and encouraged in older people at risk of falling, especially when prescribed for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium or insomnia. If antipsychotics are still needed, we recommend that the benefits and harms of antipsychotic use should be reassessed within two to four weeks of prescription. If the use of antipsychotic causes more harm than benefit, the deprescribing process should be started.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antipsychotics have been in use for about 70 years for the management of psychotic disorders, mainly schizophrenia [1]. The first typical antipsychotics developed, such as levomepromazine and later haloperidol, mainly block dopamine D2 receptors [1, 2]. Newer atypical antipsychotics like risperidone may also block dopamine D1 and D4 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors. According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis antipsychotics increase the risk of falling by about 50% in older adults [3].

The use of antipsychotics in the USA varies by age groups, reaching 1.5% in adults between 60–64 years old and rising to 2.1% in those aged 80–84 years [4]. In European countries, the use of antipsychotics in home-care patients varies from 3.0 to 12.4% [5], rising to 26.4% in the nursing home setting [6] and to 35.6% if only considering residents with severe cognitive impairment [7]. According to the recent Canadian Institute for Health Information report, 22% of residents in long-term care homes were treated with antipsychotics without a proper indication [8].

The most common (off-label) indications for antipsychotic use among older adults, especially those with cognitive decline, are neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia and delirium. Over 55 million people –mainly older adults– are diagnosed with dementia globally [9]. More than 90% of persons with cognitive disorders experience neuropsychiatric symptoms at least at some point during their disease process [10]. The three most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with cognitive impairment initiating antipsychotics were agitation/aggressiveness (27%), irritability (23%) and depression (16%) [11]. Antipsychotics are commonly given for the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in older people with dementia despite the known potential risk of adverse events and mainly with off-label indications [12]. Antipsychotic use is common in community-dwelling people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (24%) [13], rising 2–3 years before formal diagnosis [14]. Risperidone (54%), quetiapine (30%) and haloperidol (6%) were the three most frequently used long-term antipsychotics in people with AD [15]. Dementia itself is associated with a higher rate of falling [16], and incident hip fracture risk is over two-fold in the AD population [17].

Delirium is a serious health condition, and its prevalence varies from 7 to 35% in older adults in the emergency department [18] to 49% in hospitalized older people with dementia in intensive care units and surgical departments [19]. Delirium increases the risk of falling [20] and other serious outcomes, and it is also associated with an increased risk of death and institutionalization [21]. Symptoms of delirium have been commonly treated with antipsychotics in a variety of care settings [22,23,24]. However, according to a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis, nor was it associated with changes in duration or severity of delirium, length of hospital or intensive care unit stay, or mortality [24].

Nguyen et al. summarize in their review that the prevalence of insomnia symptoms among older adults reaches up to 75% [25]. Insomnia increases the risk of falling [26]. Of people with dementia or cognitive impairment, 60% to 70% have sleep disturbances [27]. Antipsychotics are not a first-line treatment for sleeping problems, but these drugs are used for insomnia [28]. In a Canadian population-based retrospective study focused on community-dwelling older adults with sleep disorders, it was found that 2.4% of the subjects included received antipsychotics, such as quetiapine (88%) or risperidone (9%) [28].

In this paper, we conducted a literature search focusing on the clinical dilemma of deprescribing antipsychotics in older people at risk of falling. We aim to provide an overview of the current knowledge on the causes for antipsychotic-related risk of falling in older adults. We aim to summarize the benefits and adverse effects for specific indications focusing on neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium, or insomnia. In addition, we collected information on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics related to the risks of falling due to antipsychotics as well as information to assist clinicians to consider the benefits and harms of (de)prescribing antipsychotics.

Search strategy

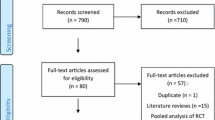

The literature search was conducted in March 2022 via CINAHL, PubMed and Scopus. The exact search terms can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Studies that focused on the reasons behind the antipsychotic-related fall risk in older adults were searched for. Included studies needed to focus on delirium, dementia and insomnia and were written in English language. Studies that focused on psychosis, schizophrenia, and psychotic symptoms, depression, mania and bipolar disorder, intractable hiccups, and post-traumatic stress disorder were excluded, unless these conditions were related to neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium, or insomnia. Studies focusing on lithium were also excluded. Studies were included if the age of the patients was 65 years or older or the mean age was 70 years or older. Only original articles, reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were included. There were no time limits for the studies. Book chapters, case reports, conference papers, congress abstracts, editorials, letters, notes, and posters were excluded. We selected all discovered studies based on title, abstract and furthermore full text to meet the aims of this study. A total of 1,287 studies were identified, and 943 studies remained after removal of 344 duplicates. Finally, 540 studies were identified as meeting the aims after title screening and furthermore 52 studies after abstract and full text screening. In addition, we included articles based on additional literature searches of papers listed in the references to find more information.

Medication review and reconciliation

It is recommended that older adults are assessed annually for fall risk, and a medication review is suggested annually for all older adults and every six months for frail or vulnerable adults [29, 30]. A medication review is based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment or a holistic examination done by a physician or an interdisciplinary team [31]. In medication review, it is important to check that all medications including antipsychotics have a current and appropriate indication and dose for their use.

Matching antipsychotic use to an appropriate indication

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the indications for antipsychotics in adults are psychotic disorders, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, treatment-resistant depression, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, agitation, generalized nonpsychotic anxiety, severe behavioural problems, hyperactivity and Tourette’s syndrome [32]. Indications vary between different drug substances. In Europe, only risperidone has an official indication for persistent aggression in patients with moderate or severe dementia of AD [33]. The use of other antipsychotics for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia and all antipsychotic use for delirium and insomnia is therefore off-label use.

Although antipsychotics are commonly prescribed for delirium, the current evidence does not support this practice [24]. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis, which included 19 studies and focused on the use of antipsychotics for the prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults found that antipsychotic use was not associated with changes in the duration or severity of delirium. As well, when considering seven studies that compared antipsychotics with placebo or no treatment for the prevention of delirium after surgery, there was no significant effect on delirium incidence [24]. Although there are conflicting studies on the usefulness of antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium [34], the first-line treatment of delirium is non-pharmacological interventions and identification and treatment of the possible underlying cause of the delirium [35]. Medications that increase the risk of delirium should be reviewed, and if possible, and deprescribed.

Atypical antipsychotics are not recommended for insomnia in older adults [36]. Although some antipsychotics, such as quetiapine and olanzapine, have sedative effects via their antagonism of the histamine H1 receptor [37], there is limited evidence on the use of antipsychotics for insomnia in older adults and their use is not recommended for the treatment of insomnia [36,37,38]. The first-line treatment for insomnia is an effective cognitive behavioural therapy [39], in addition to deprescribing drugs that may cause insomnia and treating chronic diseases and symptoms such as pain as well as possible to maintain sleep.

The first-line management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia is to identify by comprehensive clinical examination possible diseases, triggers, or other causes for these neuropsychiatric symptoms and then treatment should focus on the causes [40]. Antipsychotics are often used for neuropsychiatric symptoms, although non-pharmacological treatment options such as psychosocial interventions are first-line treatments [11, 12, 40]. Antipsychotics should be considered as a last resort when other treatment options have not been successful, in severe agitation, or when the risk of harm to self or others outweighs the potential secondary effects of the medication used [33, 40]. If antipsychotics are needed, their use should be limited to the shortest possible duration and lowest effective dose [40].

Commonly used international guidelines, such as the European Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions (STOPP) and the North American Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults, recommend avoiding antipsychotics in older adults with neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia unless the symptoms are severe and other non-pharmacological treatment options have failed [41, 42]. The Beers Criteria also include delirium and advice not to prescribe antipsychotics unless the older adult is at the risk of significant harm to self or others [42]. If there is a risk of harm, both The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and The American Geriatrics Society recommend that haloperidol for delirium can be used for a short duration, e.g., for one week or less [43, 44]. The Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk (STOPPFall) also recommends considering withdrawal of antipsychotic if they are prescribed for insomnia or for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia [45]. Usually, the doses of antipsychotics for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium and insomnia are just a minor part (such as 0.5–1.0 mg of risperidone /day) of the dose recommended for the treatment of psychosis, nevertheless the risk of adverse drug events remains high in older people, even at lower doses [24, 37, 40].

Pharmacodynamics, pharmacogenetics and drug–drug interactions

The main metabolic routes of the most used antipsychotics are described in Table 1. Additional prescribing recommendations for different types of metabolizers are also listed. Additional prescribing recommendations are given for risperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, aripiprazole, and haloperidol. There are recommendations for CYP2D6 poor and/or ultrarapid metabolizers and one for CYP3A4 poor metabolizers. In Europe, 1.2% to 12% are CYP2D6 poor metabolizers and up to 9.1% are CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers [46]. The main drug-drug interactions of the most used antipsychotics in older adults are also described in Table 1.

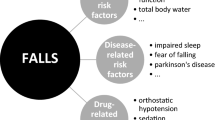

Fall-related adverse effects of antipsychotics

Antipsychotics increase the risk of falling [3]. According to a recent Delphi study by the European Geriatric Medicine Society Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs, the fall risk associated with antipsychotics is caused by several mechanisms such as their anticholinergic, sedative and extrapyramidal effects, as well as their cardio- and cerebrovascular effects and orthostatic hypotension. The prevalence of fall-related adverse effects of antipsychotics is shown in Table 2. The information is based on summaries of product characteristics.

Sedation and anticholinergic effects

Antipsychotics have sedative effects [Table 2, 50, 51] through several mechanisms [2, 37]: antagonism of histamine H1 receptors, muscarinic receptors and adrenergic α1-receptors. The typical antipsychotics haloperidol and chlorpromazine act as antagonists on all three receptors [2]. The atypical antipsychotics quetiapine and olanzapine cause sedation by antagonising the histamine H1 receptor [39]. Quetiapine is also a weak antagonist of adrenergic α1-receptors, and olanzapine is an antagonist of both muscarinic and adrenergic α1-receptors [2]. A network meta-analysis comparing the safety and efficacy of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia found no differences in sedative effects between aripiprazole, olanzapine and quetiapine. However, risperidone was found to be less sedating than quetiapine and olanzapine [50]. This has also been reported elsewhere [51].

Antipsychotics have anticholinergic adverse effects, both central (worsening of cognition, delirogenous potential) and peripheral, such as blurred vision, dry mouth, urinary retention or constipation, due to their antagonism of muscarinic receptors [Table 2, 51]. Both typical and some atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine and clozapine are associated with antagonism of muscarinic receptors [2]. However, the exact mechanism underlying the anticholinergic adverse effects of some atypical antipsychotics like risperidone and quetiapine, is still unclear.

Cardio- and cerebrovascular adverse outcomes

The FDA required a boxed warning for atypical antipsychotics in 2005, partially due to the death-risk increasing cardiovascular adverse outcomes, e.g., heart failure in people with dementia-related psychosis [52]. In 2008, the FDA extended the boxed warning requirement were extended to typical antipsychotics and the EMA made a similar recommendation [53, 54].

The use of typical [55,56,57] and atypical antipsychotics [55,56,57,58] is associated with serious cardio- and cerebrovascular adverse events, such as stroke and myocardial infarction and higher mortality. Reasons for these cardio- and cerebrovascular adverse effects include affinity to multiple receptors as described at the beginning of Sect. "Fall-Related Adverse Effects of Antipsychotics" as well as an adverse event profile including orthostatic hypotension, QTc prolongation, tachycardia, and metabolic effects. In a Welsh cohort study people with dementia receiving typical and atypical antipsychotics had a higher risk of having stroke and venous thromboembolism compared to nonusers of antipsychotics [59]. A recent Finnish register-based cohort study among people with AD who were new users of antipsychotic and matched with nonusers showed a different result [55]. There was no overall association between antipsychotic use and the risk of stroke for longer durations of antipsychotic use compared with non-use. However, during the first 60 days of use, antipsychotic initiators had a higher age-standardized incidence rate of stroke and an increased risk of stroke, as well for ischaemic stroke. In this study, risperidone (63%) and quetiapine (30%) were the most commonly used antipsychotics and there was no difference between these drugs in the risk of any stroke or ischaemic stroke. A previous Korean cohort study compared the risk of ischaemic stroke between older people taking risperidone and haloperidol and reported higher a incidence rate of ischaemic stroke among haloperidol users (6.43 /1000 person-years) than in the risperidone users (2.88/1000 person-years) [60].

Antipsychotics can cause QT prolongation by acting on cardiac ion channels [61]. If the QT time is more than 500 ms, there is a high risk of serious adverse events such as torsade de pointes and ventricular arrythmias [62]. Ziprasidone and thioridazine have a particularly high risk of prolonging QTc, quetiapine and chlorpromazine have an intermediate risk, but risperidone, clozapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, and haloperidol have a low risk of prolonging QTc.

Antipsychotics cause orthostatic hypotension via α1-adrenoceptor blockade [63]. Blocking of α1-adrenoceptors attenuates the increase in systemic vascular resistance, a response to postural change, leading to symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia. Among the typical antipsychotics, quetiapine, olanzapine, clozapine, and amisulpride have potent orthostatic hypotensive effect (Table 2). Among typical antipsychotics, a strong (orthostatic) hypotensive effect can be found with haloperidol, chlorpromazine, levomepromazine, perphenazine, droperidol, prochlorperazine, chlorprothixene, and zuclopenthixol.

Extrapyramidal effects

Both typical and atypical antipsychotics can cause extrapyramidal effects [Table 2, 50, 51, 61, 64]. The typical antipsychotics haloperidol and chlorpromazine in particular cause extrapyramidal effects [61]. The situation is less clear for atypical antipsychotics. Yunusa and colleagues conducted a network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) with placebo or head-to-head comparisons of at least two atypical antipsychotics in older adults with neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia [50]. They found that risperidone was associated with an increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms when compared with quetiapine (OR 3.75; 95% CI 1.61–8.73), whereas quetiapine had a lower risk compared to olanzapine (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.16–0.93).

Fall-related injuries associated with antipsychotics use

Antipsychotics are associated with fall related injuries like hip fractures and head injuries as adverse effects [65,66,67]. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis, antipsychotics increase the risk of fragility hip fractures with OR 1.85 (95% CI 1.36–2.51) in the general older population [65]. Koponen et al. (2017) aimed to investigate association of antipsychotic use with the risk of hip fracture in persons with AD and to compare the risk according to the duration of use and use of quetiapine or risperidone [66]. The risk of hip fracture was about the same compared to nonusers of antipsychotics among older adults with AD (aHR 1.54; 95% CI 1.39–1.70). The risk increased from the first days of use and remained elevated thereafter and the risk of hip fracture was about the same for risperidone and quetiapine users. In addition, falls can cause head injury and traumatic brain injury. In older adults with AD the antipsychotic use was associated with an increased event rate for traumatic brain injuries and the risk was higher in quetiapine users than in risperidone users [67].

Deprescribing antipsychotics to reduce fall risk

Deprescribing of antipsychotics should always be considered if there is no current indication or if there is a safer alternative available [43]. In addition, antipsychotic withdrawal should be considered when antipsychotics are prescribed for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia or for sleep disorders, and withdrawal should be considered when antipsychotics are prescribed for bipolar disorder. Deprescription should especially be considered if extrapyramidal or cardiac adverse effects, dizziness, (signs of) sedation, or blurred vision occur with antipsychotic use.

Taper and timing of deprescribing

STOPPFall, MedStopper and Deprescribing.org are some examples of tools to assist clinicians in deprescribing medication [43, 70, 71]. The STOPPFall deprescribing tool was developed by the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) Task and Finish Group on FRIDs (fall-risk increasing drugs) in collaboration with the EuGMS Special Interest Group on Pharmacology through a European expert Delphi consensus effort [43]. The expert group has developed a decision tree for antipsychotic withdrawal [43, 72]. It focuses on the prevention of falls and includes algorithms for practical deprescribing [72]. There is also a description of deprescribing process by Scott et al. [73].

The panellists contributing to STOPPFall strongly agree that stepwise withdrawal is generally needed when deprescribing antipsychotics [43]. The deprescribing process depends on the indication for which antipsychotics are being given for and on the duration of the treatment [72]. For example, if antipsychotics are being given for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia for at least three months, it is recommended that the dose be reduced by 25–50% every 1–2 weeks. If antipsychotics are given for insomnia and the likely underlying comorbidities are treated, the antipsychotic can be stopped without tapering. The MedStopper [70] recommends a 25% dose reduction each week if antipsychotics are used daily for more than 3–4 weeks. The tapering can be extended or decreased for example to a 10% dose reduction, if necessary. However, individual countries may differ in their recommendations for the timing of medication reviews after prescribing antipsychotics, e.g. in the USA tapering and stopping of antipsychotics is recommended within 4 weeks if there is no clinically relevant response and within 4 months if the medication has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms, and in Australia reassessment of the need for antipsychotic treatment is recommended within 4 to 12 weeks [68, 69]. Several studies have suggested that the time frame for reassessing should be shorter than in these clinical practice guidelines [55].

A few studies have examined the outcomes of deprescribing antipsychotics. Nursing home staff reported several benefits and barriers to reducing antipsychotics medication [74]. Benefits reported included improvements in the quality of life, family satisfaction and reductions in falls and injuries. Barriers included return or worsening of symptoms, lack of effectiveness and/or lack of staff resources for non-pharmacological management strategies and family resistance.

Monitoring during and after deprescribing

After deprescribing, stopping or dose reduction, it is recommended to monitor for changes in symptoms e.g., orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, fall incidents and recurrence of symptoms including aggression, agitation, delusion, hallucination, and psychosis [43, 72]. It is also recommended to consider monitoring of insomnia. Furthermore, follow-ups are advised to be organized based on an individual basis, e.g. according to the severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms or insomnia at the baseline and possible withdrawal symptoms [72].

Conclusions

Antipsychotics are used for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium and insomnia in older adults despite the lack of proven efficacy and official indications. Neuropsychiatric symptoms should be assessed, and the causes should be thoroughly identified and treated. If symptoms persist after non-pharmacological interventions the syndromes could be treated with pharmacological treatments. Antipsychotics may be used only if other treatments have not been successful, or if the patient is severely agitated or at the risk of harm to self or others [10]. If antipsychotics are needed, they should be started and used at the lowest effective dose and used for as short a time as possible. It is important to remember that neuropsychiatric syndromes, delirium, and insomnia increase the risk of falling regardless of pharmacological treatment. In addition, antipsychotics increase the risk of falling through anticholinergic and extrapyramidal effects, sedation, (orthostatic) hypotension, and severe cardio- and cerebrovascular adverse effects. In addition, drug-drug interactions may increase the risk of falling because of possible increased exposure to antipsychotics and adverse effects.

The European STOPPFall tool recommends deprescribing antipsychotics if they have no indication, if they are prescribed for insomnia or neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, are ineffective or have severe adverse drug related effects. The deprescribing should also be considered if the patient experiences cardiac or extrapyramidal side effects, sedation, signs of sedation, blurred vision or dizziness. STOPPFall recommends that stepwise withdrawal is generally needed when deprescribing antipsychotics. When deprescribing antipsychotics, it is recommended to monitor for recurrence of symptoms such as aggression, agitation, delusions, hallucinations and psychosis, and to consider monitoring for insomnia.

References

Shireen E (2016) Experimental treatment of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders. J Experiment Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.2147/JEP.S63553

Hollister LE (2000) Psychiatric disorders. In: Melmon and Morelli’s Clinical Pharmacology, editors. 4th edn. The United States of America, pp 429–528

Seppälä LJ, Wermelink AMAT, de Vries M et al (2018) Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Psychotropics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.098

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M (2015) Antipsychotic treatment of adults in The United States. J Clin Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m09863

Alanen HM, Finne-Soveri H, Fialova D et al (2008) Use of antipsychotic medications in older home-care patients report From Nine European countries. Aging Clin Exp Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03324781

Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D et al (2012) Polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr233

Vetrano DL, Tosato M, Colloca G et al (2013) Polypharmacy in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. Alzheimers Dement. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.009

CIHI (2021) Potentially inappropriate use of antipsychotics long-term care. In Your Health System: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/inbrief?lang=en#!/indicators/008/potentially-inappropriate-use-of-antipsychotics-in-long-term-care/;mapC1;mapLevel2;overview. Accessed 11 Aug 2022

Dementia (2021) World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia Accessed 5 Jul 2022

Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Finnish Current Care Guidelines for Memory Disorders. Duodecim. https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi50044. Accessed 14 Jul 2022

Kuronen M, Kautiainen H, Karppi P et al (2016) antipsychotic drug use and associations with neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with impaired cognition: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2016.1191537

Capiau A, Foubert K, Somers A et al (2021) Guidance for appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in older people. Eur Geriatr Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00439-3

Orsel K, Taipale H, Tolppanen A-M et al (2018) Psychotropic drugs use and psychotropic polypharmacy among persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.04.005

Koponen M, Tolppanen AM, Taipale H et al (2015) Incidence of antipsychotics use in relation to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease among community-dwelling persons. Br J Psych 207(5):444–449

Koponen M, Taipale H, Tanskanen A et al (2015) Long-term use of antipsychotics among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide register-based study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.008

Stubbs B, Perara G, Koyanagi A et al (2020) Risk of hospitalized falls and hip fractures in 22,103 older adults receiving mental health care vs 161,603 controls: a large cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.005

Tolppanen A-M, Lavikainen P, Soininen H et al (2013) Incident hip fractures among community dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease in a finnish nationwide register-based cohort. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059124

Silva LOJE, Berning MJ, Stanich JA et al (2021) Risk factors for delirium in older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.03.005

Han QYC, Rodrigues NG, Klainin-Yobas P et al (2022) Prevalence, risk factors, and impact of delirium on hospitalized older adults with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.09.008

Oren G, Jolkovsky S, Tal S (2022) Falls in oldest-old adults hospitalized in acute geriatric ward. Eur Geriatr Med 13(4):859–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-022-00660-2

Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, Se Jonghe JFM et al (2010) Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1013

Swan JT, Fitousis K, Hall JB et al (2012) Antipsychotic use and diagnosis of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11342

Egberts A, Alan H, Ziere G et al (2021) Antipsychotics and lorazepam during delirium: are we harming older patients? A real-life data study. Drugs Aging. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00813-7

Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN et al (2016) antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14076

Nguyen V, George T, Brewster GS (2019) Insomnia in older adults. Curr Geriatr Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-019-00300-x

Vieira ER, Freund-Heritage R, da Costa BR (2021) Risk factors for geriatric patient falls in rehabilitation hospital settings: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511400639

Wennberg AMV, Wu MN, Rosenberg PB et al (2018) Sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, and dementia: a review. Semin Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604351

Pop P, Bronskill SE, Piggott KL et al (2019) Management of sleep disorders in community-dwelling older women and men at the time of diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16038

Seppälä LJ, van der Velde N, Masud T et al (2019) The EuGMS task and finish group on fall-risk-increasing drugs (FRIDs): position on knowledge dissemination, management, and future research. Drugs Aging. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0622-7

Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC et al (2022) Task force on global guidelines for falls in older adults: world guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing 51:afac205

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E et al (2015) Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 175:827

Christian R, Saavedra L, Gaynes BN et al (2012) Appendix A: tables of FDA-approved indications for first- and second-generation antipsychotics. In: Future research needs for first- and second-generation antipsychotics for children and young adults. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville

Risperidal. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/risperdal. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Kishi T, Hirota T, Matsunaga S et al (2015) antipsychotic medications for the treatment of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-311049

Igsleder B, Frühwald T, Jagsch C et al (2022) Delirium in geriatric patients. Wien Med Wochenschr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-021-00904-z

Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL et al (2016) Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010

Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G et al (2018) Drugs for insomnia beyond benzodiazepines: pharmacology, clinical applications, and discovery. Pharmacol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.117.014381

Thompson W, Quay TAW, Rojas-Fernandez C et al (2016) Atypical antipsychotics for insomnia: a systematic review. Sleep Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.04.003

Van Straten A, Van der Zweerde T, Kleiboer A et al (2018) Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.02.001

Phan SV, Osae S, Morgan JC et al (2019) Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: considerations for pharmacotherapy in the USA. Drugs R D. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-019-0272-1

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S et al (2015) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu145

Beers criteria (DDIs): Fick DM, Semla TP, Steinman M, et al (2019) American geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS Beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

Seppala LJ, Petrovic M, Ryg J et al (2021) STOPPFall (screening tool of older persons prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk): a Delphi study by the EuGMS task and finish group on fall-risk-increasing drugs. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa249

The American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults (2015) American geriatrics society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. JAGS. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13281

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2019) Delirium: prevention, diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/chapter/Recommendations#treating-delirium. Accessed 31 Aug 2022

Koopmans AB, Braakman MH, Vinkers DJ et al (2021) Meta-analysis of probability estimates of worldwide variation of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. Transl Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01129-1

Wijesinghe R (2016) A review of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions with antipsychotics. Ment Health Clin. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2016.01.021

The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB). https://www.pharmgkb.org/. Accessed 12 Jul 2022

Clozapine tablet (Package insert). Sun Pharmaceutical Industries. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=53bdb79c-c4cf-4818-b1f0-225e67a14536. Accessed 17 Mar 2021

Yunusa I, Alsumali A, Garba AE et al (2019) Assessment of reported comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. JAMA Netw Open. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0828

Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S (2011) Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1360

US Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170113112252/http:/www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053171.htm. Accessed 22 Jun 2022

EMA boxed warning: European Medicines Agency (EMA) (2008) CHMP assessment report on conventional antipsychotics. procedure under article 5(3) of regulation (EC) No 726/2004. EMEA/CHMP/590557/2008. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2010/01/WC500054057.pdf. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

US Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: conventional antipsychotics. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722190727/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Accessed 22 Jun 2022

Koponen M, Rajamäki B, Lavikainen P et al (2021) Antipsychotic use and risk of stroke among community-dwelling people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.09.036

Yu ZH, Jiang HY, Shao L et al (2016) Use of antipsychotics and risk of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12985

Koponen M, Taipale H, Lavikainen P et al (2017) Risk of mortality associated with antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160671

Yunusa I, Rashid N, Demos GN et al (2022) Comparative outcomes of commonly used off-label atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of dementia-related psychosis: a network meta-analysis. Adv Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02075-8

Dennis M, Shine L, John A et al (2017) Risk of adverse outcomes for older people with dementia prescribed antipsychotic medication: a population based e-cohort study. Neurol Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-016-0060-6

Shin J-Y, Choi N-K, Lee J et al (2015) A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly: a propensity score-matched cohort analysis. J Psychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115578162

Solmi M, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I et al (2017) Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. https://doi.org/10.2147/2FTCRM.S117321

Gareri P, De Fazio P, Manfredi VGLM et al (2014) Use and safety of antipsychotics in behavioral disorders in elderly people with dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182a6096e

Gugger JJ (2012) Antipsychotic pharmacotherapy and orthostatic hypotension. CNS Drugs. https://doi.org/10.2165/11591710-000000000-00000

Ma H, Huang Y, Cong Z et al (2014) The efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Alzheimer’s Dis. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-140579

Mortensen SJ, Mohamadi A, Wright C et al (2020) Medications as a risk factor for fragility hip fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Calcified Tissue Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-020-00688-1

Koponen M, Taipale H, Lavikainen P et al (2017) Antipsychotic use and the risk of hip fracture among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m10458

Tapiainen V, Lavikainen P, Koponen M et al (2020) The risk of head injuries associated with antipsychotic use among persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16275

American Psychiatric Association (2016) The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890426807

Guideline Adaption Committee (2022) Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia. https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Dementia-Guideline-Recommendations-WEB-version.pdf. Accessed 12 Jul 2022

MedStopper (2022) https://medstopper.com/. Accessed 3 Aug 2022

Desprescribing.org (2022) https://deprescribing.org/. Accessed 3 Aug 2022

Decision tree (2022) https://kik.amc.nl/falls/decision-tree/. Accessed 3 Aug 2022

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E et al (2015) Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324

Simmons SF, Bonnett KR, Hollingswoth E et al (2018) Reducing antipsychotic medication use in nursing homes: a qualitative study of nursing staff perceptions. Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx083

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors are required to disclose financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication. Netta Korkatti-Puoskari, Miia Tiihonen, Maria Angeles Caballero-Mora, Eva Topinkova and Katarzyna Szczerbińska have no conflict of interests, Sirpa Hartikainen has got lecture fees from Eisai ltd.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not required for this type of study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korkatti-Puoskari, N., Tiihonen, M., Caballero-Mora, M.A. et al. Therapeutic dilemma’s: antipsychotics use for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium and insomnia and risk of falling in older adults, a clinical review. Eur Geriatr Med 14, 709–720 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00837-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00837-3