Abstract

In the 1930s, Shenandoah National Park was established in the Virginia Blue Ridge through the displacement of nearly 500 white families. In recent decades, my scholarship and that of others focused upon the manner in which hackneyed stereotypes about backward mountaineers were mobilized to garner public support for the condemnation of family farms and, in some cases, the institutionalization, sterilization, and incarceration of some of the most impoverished. But, in focusing solely upon the 20th century and the impacts on the white displaced, this research has perpetrated structural violence by obscuring the role of race and racism in the wider Blue Ridge. Archaeological and documentary evidence from the 1990s National Park Service–funded “Survey of Rural Mountain Settlement” is reexamined and reconsidered to begin the process of redressing the silencing of African American histories in the Blue Ridge and surrounding valley and piedmont regions.

Resumen

En la década de los 1930, el Parque Nacional Shenandoah se estableció en la cordillera Azul de Virginia, mediante el desplazamiento de casi 500 familias blancas. En las últimas décadas, mi investigación y la de otros se centraron en la forma en que se movilizaron los estereotipos trillados sobre los montañistas atrasados para obtener apoyo público para la condena de las granjas familiares y, en algunos casos, la institucionalización, esterilización y encarcelamiento de algunos de los habitantes más empobrecidos. Pero, al centrarse únicamente en el siglo XX y los impactos en los desplazados blancos, esta investigación ha perpetrado la violencia estructural al oscurecer el papel de la raza y el racismo en la cordillera Azul más amplia. La evidencia arqueológica y documental de la “Encuesta de asentamientos rurales de montaña” financiada por el Servicio de Parques Nacionales de la década de 1990 es reexaminada y reconsiderada para comenzar el proceso de corregir el silenciamiento de las historias afroamericanas en la cordillera Azul y las regiones circundantes de valles y piedemonte.

Résumé

Dans les années 1930, le parc national de Shenandoah a été établi dans le Blue Ridge de Virginie entraînant le déplacement d'environ 500 familles blanches. Au cours des récentes décennies, ma recherche et celle d'autres chercheurs s'est intéressée à la manière dont les stéréotypes galvaudés relatifs aux habitants attardés des montagnes ont été mobilisés pour recueillir le soutien du public à l'appui d'une condamnation des fermes familiales et, dans certains cas, du placement en institution, de la stérilisation et de l'incarcération de certains parmi les plus pauvres. Mais cette recherche axée uniquement sur le 20ème siècle et les conséquences pour les populations blanches déplacées, a perpétré une violence structurelle en dissimulant le rôle de la race et du racisme dans la région plus vaste du Blue Ridge. Les preuves archéologiques et documentaires issues de l’« Étude du peuplement des montagnes rurales » financée dans les années 1990 par le Service des Parcs nationaux, sont réexaminées et reconsidérées pour initier le processus correctif de la mise sous silence des histoires africaines-américaines du Blue Ridge et des régions environnantes de la vallée et du piedmont.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Honesty and self-reflection must be at the core of ethical archaeological practice. This is uncontroversial as a principle, but rather more challenging in practice, particularly when we archaeologists take the time to look back at our own work as well as position ourselves in the lived present. In the discussion that follows, I revisit a project that I conducted in the Virginia Blue Ridge in the 1990s and reconsider the ethical implications of my own research. An honest self-critique highlights unintended failures in my approach and illuminates my own culpability in amplifying one narrative over another. As scholars of the past, we always choose what narratives we wish to emphasize, very often motivated by social-justice issues. That is precisely what I thought I was doing at the time. Instead, I implicated myself in the perpetuation of structural violence. Ongoing self-reflection has allowed me to reorient my perspective and initiate a revised program of research to addresses past erasures toward producing a much more holistic, critical, and inclusive narrative.

The project was a multiyear examination of historical settlement and 20th-century displacement in the Virginia Blue Ridge, focusing upon three historical communities, each of which had been displaced through the creation of Shenandoah National Park in the 1930s. Shenandoah National Park encompasses an approximately 280 sq. mi. portion of the Blue Ridge Mountains in northwestern Virginia. Long celebrated for its natural wonders, including complex geology, native flora, and thriving wildlife, the lands incorporated within the national park had also been home to human populations for at least 10,000 years. By the time of park establishment (the park was officially dedicated in 1936 following a decade of planning), approximately 500 European American families had been displaced. They left behind evidence of their homes, farms, businesses, schools, churches, and cemeteries, often superimposed on a dense record of Native American activity. While many of the abandoned buildings were dismantled, others were merely left to decay. Although there was a movement at the time of park creation to retain and interpret a small selection of historical buildings in the park, the effort faltered and was forgotten. Fields and roads soon became overgrown, first with underbrush and eventually with mixed hardwoods. In the parlance of the National Park Service management, Shenandoah was rendered “natural” and administered as such (Horning 1998; Krumenaker 1998).

Management priorities changed, and, in the 1990s, as part of a broader national effort to assess the presence and condition of archaeological resources across federal lands, funding was made available for cultural resource work in Shenandoah. I was privileged to take the lead on two projects funded by the National Park Service through a cooperative agreement with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. One was an “Overview and Assessment” of all known archaeological resources in the park (Horning 2007), and the other was the multiyear “Survey of Rural Mountain Settlement” (Horning 1998, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2001, 2002, 2004). It is this latter project that I want to revisit and reconsider. The new light that I wish to cast on this project and the historical archaeology of the park more broadly is one that illuminates the realities of racism in the broader park region and the impact of structural violence in shaping the histories of settlement, of displacement, and of scholarship on the Blue Ridge as it has come to be defined by a narrow focus on the Shenandoah National Park case. I argue that an insidious, if unintended, outcome of park creation has been the erasure of the African American history of the region. This is a process long in the making. Two entries for the year 1925 in a popular history of Madison County serve as a stark reminder of the concomitant rise of anti-black sentiment with the movement for the park: “The first meeting concerning the creation of a national park in the Blue Ridge was held. ... Ku Klux Klan held a meeting” (Davis 1977:303). Subsequent considerations of park-area history have focused on the experiences of European Americans, because the whiteness of the early 20th-century displaced inhabitants of the park area has been taken to mean that the entirety of the history of the Blue Ridge is, de facto, a white history. This presumption is at odds with both broader regional experiences and the specifics of the 18th- and 19th-century archaeological and historical evidence from the park itself. In short, this article begins the process of addressing the African American history of the Shenandoah National Park region by confronting its historical silencing. But, before addressing this critique, a bit of background is required.

Background

The focus of the “Survey of Rural Mountain Settlement” was on Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley hollows, which lie in the park’s central district within Madison and Rappahannock counties (Fig. 1). These three hollows had been the subject of a 1933 pseudo-scholarly study, Hollow Folk, by the University of Chicago psychologist and eugenicist Mandel Sherman writing with a Washington-based reporter, Thomas Henry. The book purported to analyze the cultural backwardness of the inhabitants and drew upon decades of tropes about isolated, degenerate hillbillies to galvanize public opinion in favor of removal of the residents. Sensationalized descriptions emphasized lack of education, poverty, and what were presented as genetically based character flaws (Sherman and Key 1929, 1932; Sherman and Henry 1933). Ultimately, over 4,000 individual land tracts were purchased or condemned by the Commonwealth of Virginia and presented to the federal government for the park (Engle and Janney 1997). In the 1990s, when I began the research, local memories about displacement were very strong (and they remain so to this day), even as the physical traces of habitation lay obscured in the hardwood forests. But what remained visible on the ground clearly challenged the conclusions of Hollow Folk and the rhetoric of park boosters. Surface artifacts, in particular, spoke to engagement with regional and national commercial networks in the form of abundant tin cans, pharmaceutical and cosmetic bottles, ready-made clothing and shoe fragments, and even automobile parts. Far from living in a “medieval age” (Sizer 1932:n.p.), as described at the time, mountain residents engaged with the popular culture of the 1930s, evidenced most graphically by the archaeological recovery of fragments 78 rpm records and abundant toys, including a Buck Rogers–style ray gun and a porcelaneous Steamboat Willie (aka early “Mickey Mouse”) figurine (Horning 2019).

Hollows study area, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia (Horning 2002:132).

In addition to mobilizing the archaeological record to challenge the “Dogpatch” version of history peddled by Sherman and Henry, I was interested in piecing together the full historical settlement of the three hollows. Alongside the extensive field survey of 61 historical sites, surface collecting and subsurface testing on a sample of those sites, and ethnographic research with the displaced and their descendants, I researched the full property histories of each land tract within the ca. 2,500 ac. study area. Reconstructing property histories over several hundred years by thumbing through deed books in three different county courthouses was as exciting to me as discovering a collapsed stone chimney on the same piece of land I was tracing in the records. The searches went hand in hand, one informing the other, and were often disrupted in unexpected ways through conversations and interviews with former occupants, providing rich insights on the lived experience of life in the hollows. Sometimes the documentary archives remained frustratingly silent. Other times the records yielded remarkable surprises, as was the case with a chance discovery of a small, loose piece of paper stuck in an unrelated set of chancery papers in the Madison County courthouse that provided rare (if incomplete) insight into family and community dynamics in the early 19th-century hollows. The story associated with that scrap of paper serves as a prelude to and pivot point for the reconsideration of race, racism, and inequality in the Shenandoah National Park region that follows.

A Family Tale

According to the scrap of paper, dated 18 July 1818, Weakley Hollow resident William Hurt entered an agreement with William Taylor and Thomas Chapman, “overseers of the poor,” to bind James Corbin (aged 18), Cornelius Corbin (aged 16), Eveona Corbin (aged 14), Jefferson Corbin (aged 12), Ebbalina Corbin (aged 10), Andrew Corbin (aged 9), Edwin Corbin (aged 7), Israel Corbin (aged 6), William Corbin (aged 4), and Mary Corbin (aged 1) “to be an apprentices with him the said William Hurt” until the boys reached the age of 20 and the girls 18 (Madison County Chancery Records 1818). The boys were to be trained as farmers, while the girls were to learn spinning and weaving. Furthermore, Hurt agreed to “teach or cause to be taught to the said Children reading writing and common arithmetic including the rule of three and will moreover pay to the said children the sum of twelve dollars each at the expiration of the aforesaid term.” William Hurt was in a strong position to fulfill his promises, not only being the son of a landowner, but from a slaveholding family. The significance of Hurt’s familiarity with the institution of slavery provides my departure point for discussion in the second half of this article. I deliberately prioritize the tale of the Hurt family in this first section to shape my later consideration of archival erasure and a reframing of understandings of hollows life.

I pondered long and hard over the question of why William Hurt would take in 10 children. Only two Corbin households were listed as residing in Madison County in 1810: Hannah Corbin, heading up a household of five females (one >45, one >25, one 16–25, one 10–15, and one <10 years of age), and John Corbin heading up a household of two: himself and a male aged 16–25. A further 18 Corbin households were enumerated for adjacent Culpeper County (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1810). Unfortunately, the only names recorded on the federal census of that year are those of the head of household. By 1820, there were 4 Corbin households in Madison County, but with no easily discernible direct relationship to the 10 children. Three of the 1820 Madison County Corbin households were composed of young families, while the fourth consisted of Thomas Corbin (aged >45) and a female >45, presumably his wife (no name was recorded) (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1820). Perhaps the children were those of Thomas Corbin and his wife, if they were unable to look after them, or the children may have been the offspring of Reuben Corbin of Culpeper County. His listing in the 1810 census (eight years before the indentures) matches with the ages of the Corbin children named in the indentures; namely (in 1810), three boys and two girls under age 10. But, as a Culpeper County resident, why would his children become the responsibility of the Madison County overseers of the poor?

I found a partial answer in the marriage records, which revealed that a little over a month after the apprenticeships were agreed––on 8 September 1818––William married one Fannie Corbin, thenceforward referred to as “Frances.” The names of her parents were not recorded. Were the 10 children hers? or perhaps siblings? Did she hold out on agreeing to marriage until the children were given legal status and support? Certainly a family relationship is implied, and ultimately the 10 children became more than mere apprentices to William Hurt. Long after the expiration of agreed terms of their apprenticeships, each was left a substantial bequest in his will (written in 1834, proved in 1843), where they were specifically referred to as his children (Madison County Will Book 1834). For example, the will specified: “I give my wife Frances and son Israel the house tract, as it is my wish that they should farm together.” Israel (now with the surname of Hurt) appears to have been a favorite, as he was also named as executor of Hurt’s estate. James and Jefferson were each granted 100 ac. and their houses on those lands, Andrew was left $100, while Cornelius and Edwin each received $50. Ebbalina (now Ramsbottom) received the remaining part of Hurt’s “lower tract,” while Eveony (now Bradley) and Mary received $100 each (Madison County Will Book 1834).

Israel Hurt followed his father’s wishes, remaining on the land tract first acquired by the Hurt family in the late 18th century. Hurt owned 171 ac. in Weakley Hollow, land first patented in 1750 by the first European American settler in the hollow, Archibald Dick. At the time of park creation, a six-room, log-and-frame home described as dating back to the time of the Dick patent still stood on the land, occupied by the erudite postmaster William Brown, who was immortalized reading a book in his study in a photograph by the Farm Security Administration photographer Arthur Rothstein (1935) (Fig. 2)—the antithesis of a backward mountain man. But I digress. In addition to materials directly related to Postmaster Brown’s residency, subsurface testing on the Brown-Hurt-Dick property stretched back to the initial Hurt occupation, given the presence of stem fragments from imported white ball-clay tobacco pipes and sherds of creamware and pearlware.

Interior of Postmaster Brown's home at Old Rag, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, 1935 (Rothstein 1935).

In 1850, this 18th-century dwelling was home to Israel Hurt and his new family. In that year he married 25-year-old Sarah (Susan) Jones, who brought a 7-year-old boy, Montella Jones (his relationship to Susan is unclear in the records), into the Hurt family home (Vogt and Kethley 2011:43). In 1853, a daughter named Susan Frances was born to Israel and Susan. But when Susan Frances was just five years old her father Israel died intestate, having been predeceased by his wife (Madison County Will Book 1858; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1860b). Circumstantial evidence, including naming practices, suggests that Susan may have died in childbirth. In any event, young Susan Frances went to live with her aunt Eveony (Corbin Hurt) Bradley and uncle William Bradley. Montella Jones was sent away. The 1860 census lists him in the Genkins household of Clarksburg, Virginia, presumably as an apprentice or a laborer (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1860a).

An inventory of Israel Hurt’s goods indicates that the ancestral Hurt home was filled with an array of furniture (beds, tables, chairs, trunks, a desk, and a bookcase), linens, books (including two atlases), two sets of dishes, a clock, a churn, looms, and casks of wine, brandy, and vinegar; while the barns and outbuildings housed horses and tack, livestock, a carriage and a farm wagon, an apple mill, a still, a pistol and a rifle, woodworking tools, a pocketknife, a wheat fan, plows, corn, cabbages, and other crops (Madison County Will Book 1858). The sale of Israel Hurt’s property was attended by neighbors from the surrounding hollows, their purchases speaking eloquently of the circulation of objects through localized kin and community networks (Horning 2004:84–85). Unfortunately, the sale was insufficient to clear Hurt’s debts, precipitating a family squabble over rights to his land and money to be provided to care for the orphaned Susan Frances. This dispute is outlined in excruciating detail in a 210-page-thick chancery file (Madison County Chancery Orders 1887). The child was “entirely dependent upon an aunt” (Eveony Hurt Bradley), described as “greatly inconvenienced” by “the support of her niece” (Madison County Chancery Orders 1887:4). Meanwhile, the Hurt farm was left “unimproved,” and the house fell into a dilapidated state (Madison County Chancery Orders 1887:4). Ultimately, the Israel Hurt property was sold off to settle the suit.

Reflection

I found piecing together stories, such as that of the Corbin-Hurt family, and what those stories said about family and community relations, as well as the role of litigation in 19th-century rural life, absolutely fascinating. I could imagine myself to be a proper historian. But I really got involved in the research because of the archaeology and how it contradicted lazy stereotypes about poor mountain whites. I was incensed at the treatment of the displaced and furious that narratives about the people of the Blue Ridge overlooked the obvious evidence lying on the ground. I wrote and talked a lot about how the material culture belied stereotypes, e.g., Horning (2001). I was humbled by my conversations with the displaced and their families, and worked hard to restore to them some dignity through bringing to light the archival and archaeological evidence. But, in so doing, I also added to what seems to be an industry of examining the Blue Ridge experience from the lens of displacement; see, e.g., Gregg (2010), Perdue and Martin-Perdue (1979–1980), and Powell (2007, 2009, 2013). The stories of the historical Blue Ridge are now always about its end, not its beginning, negotiations, and nuances. When William Hurt adopted the Corbin children, he did so not knowing that some of the other Corbin descendants would be forcibly removed from their families, hauled off to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and the Feebleminded in Lynchburg, and forcibly sterilized (Lombardo 2008; Powell 2013). This is a grim legacy of the park-creation movement, when poor whites became the target of eugenicists. But this future is not one that could have been anticipated in the early 19th century, particularly not by William Hurt, conditioned by the racial hierarchies of Virginia slave society. What I missed at the time, as I pondered the construction(s) of whiteness and explored the othering of Southern mountain whites, is how this particular narrative of displacement and of the Blue Ridge doubly dispossessed the many African Americans who were also part of the story of the hollows, particularly in the earliest years of historical settlement.

Racism and Research

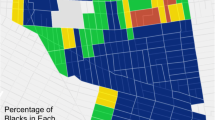

The African American history of the Shenandoah National Park vicinity has been willfully forgotten in dominant regional narratives, much as it has been overlooked or deemphasized elsewhere in the southern Appalachians; see Barnes (2011), Dunaway (1995), Silber (2001), and Inscoe (1994, 2001). Because all of the directly displaced park families were identified as white, the existence of African American landowners in the park region has elicited little comment. Park records indicate that an 812 ac. parcel of park land in Augusta County (not then inhabited) was owned by the heirs of the estate of John West, who was identified as African American (State Commission on Conservation and Development Land Records 1869–1995; Lambert 1989:178). Others, including members of the Barber, Blair, Blakey, Jones, and Simmons families owned lands within the original planned extent of the park before its size was reduced from an original 321,000 ac. to the final 176,429 ac. (Engle 1998b:10n7; Powell 2007:174n22). These African American families may have been the minority at the time of park establishment, but it is crucial to note that the early 20th-century population of the park area itself was less diverse than it had been during the century and a half beforehand, and less diverse than was all of the surrounding region in the early 20th century––a region in which park people were fully enmeshed. To generalize in the present about the Blue Ridge experience relying only on evidence from within the 1930s park boundaries is to artificially separate and obscure the realities of the past, a past in which white Blue Ridge communities were dependent upon (and at times full participants within) the slave-based economy as well as wholly implicated in the racist realities of postbellum Jim Crow Virginia. Those realities would play out in very visible ways in the early years of the park itself, when recreational facilities were segregated in deference to Virginia’s racist laws, but in violation of National Park Service policy (Lambert 1989:266; Engle 1998a:35).

Trying to recapture the long-overlooked African American history of the Blue Ridge is part of a larger regional dynamic whereby the presence of slavery has been intentionally deemphasized and downplayed. Ann Denkler (2001) examined nearby Luray, Page County, and in ethnographic interviews with local white citizens was repeatedly told that there was little to no history of enslavement or of historical black communities: “[O]ver and over, my White informants and written sources indicated that African Americans were not here in great numbers,” running counter to the continuing existence of a geographically segregated African American population within the town. Denkler highlights a notation for “Darktown” on an 1885 town map corresponding to an area on the western side of 21st-century Luray that remains primarily African American (Denkler 2001:61). The work of Shenandoah Valley historian John Wayland, writing in 1957, set the tone for this avoidance of any discussion about slavery or the contributions of African Americans to valley life:

In speaking of the various race elements, we must not overlook the Negroes. They have never been numerous in the Shenandoah Valley. ... The Germans, as a rule, were opposed to slavery—very few of them had slaves. The Quakers, too, opposed it. The majority of slaves in the Valley were held by the English from east of the ridge and by the Scotch-Irish, but even among them slaves were by no means numerous. ... From the days of the first settlement the majority of the families lived on rather small farms and did their own work. (Wayland 1989:83)

Wayland clearly wished to promote what has become the prevailing trope of the Shenandoah Valley—that of a prototypical American landscape, replete with farmers engaged in small-scale agricultural production, entwined in a close-knit economic and social relationship with their neighbors and kin, and sharing in a rich ethnic heritage. This view, which, in promoting white self-sufficiency, aims to absolve valley inhabitants of any responsibility for slavery and racism, is not supported by the evidence.

In the 1760s, 10% of the Shenandoah Valley farming families owned enslaved workers, with a higher concentration of slave owning in the lower (northern) valley adjacent to the area that would become Shenandoah National Park. By 1783, 38% of households in Frederick County, just north of the park, included enslaved people, compared to 22% in the upper valley in 1782 (Mitchell 1972:484). The Shenandoah Valley was also home to a small but notable community of free people of color. Rockbridge County in 1790 included 41 individuals categorized as such, alongside 682 enslaved people (Eslinger 2000:195). Significant numbers of enslaved and free Africans and African Americans resided in the valley market town of Winchester. In 1800, fully 16% of the town’s population consisted of enslaved people, with “a smaller, but significant, number of free Blacks” (Hofstra 2004:318); see also Ebert (1986). Both groups participated within the commercial economy, as evidenced through extant account books: “In the picture that emerges in these accounts, free and enslaved African Americans worked for goods, credit, or cash in the local economy and traded on their own account in town shops” (Hofstra 2004:319). Participation in the local market, however, was no compensation for freedom for the enslaved. In the dominant hiring-out system, individuals were often paid cash incentives that allowed for the exercise of some individual agency. However, it should not be forgotten that those incentives were specifically designed to reinforce rather than lessen discipline and control (Starobin 1968).

The institution of slavery, as it manifested in the greater Shenandoah National Park region, differed from the traditional tidewater model of large workforces confined to sizable plantations. The hiring-out system may have allowed for greater mobility and the maintenance of communication networks, but the practice of slaveholders owning, on average, between one and five enslaved individuals challenged the maintenance of family relationships and imposed a degree of intimacy between black and white that likely intensified inherent injustices more often than it did ameliorate them. Those who were only hired out for short periods were also subject to abuse, as evidenced in early 20th-century oral histories of formerly enslaved people. Henry Buttler (1941:180), who had been enslaved in Fauquier County to the northeast of Madison County, recalled one incident when he and others had been hired out to erect a fence line: “It was sundown when we laid the last rail but the overseer put us to rolling logs without any supper and it was eleven when we completed the task. Old Pete, the ox driver, became so tired he fell asleep without unyoking the oxen. For that, he received 100 lashes.” Furthermore, the hiring-out system routinely, if only temporarily, separated individuals of the same household, as the prevailing pattern was one in which an owner would hire out on an individual basis; in other words, three enslaved people in the same household could be sent to three different farms or industries (Zaborney 1997:94).

Employing that model, the major roads that traverse the park area were built by both free and hired-out enslaved labor, materially indexing their presence on the landscape. For example, in the 1780s, the Thornton Gap Road (now U.S. Route 211), which connected piedmont to valley, was improved by enslaved laborers who graded the road and surfaced it with stone under the direction of either Andrew Barbee (Lambert 1989) or William Russell Barbee (Steere 1935). Other enslaved workers were hired out to perform industrial labor, particularly in ironworks on the western slopes of the park and into the Shenandoah Valley. In the 1780s, the Pennsylvania German Dirck Pennybacker established an iron furnace, Redwell, on the banks of Hawksbill Creek in the valley. His workforce included enslaved African American laborers, who not only operated the furnace, but also labored in the mountain forests to produce the massive amounts of charcoal required to fuel the foundry (Lewis 1979; Lambert 1989:75–76). Extant account books for the Redwell furnace detail the names of some of the enslaved men who were compelled to labor at Redwell: “Reuben Negroe,” “Black Joseph,” “Moses Negroe Little” (Lewis 1979:27). Inside the boundaries of Shenandoah National Park in Rockingham County lie the substantial remains of the Mount Vernon Furnace complex, established in 1830 and also dependent upon unfree labor (Horning 2007:92–93; Ellis 2011). Similarly, the exploitation of copper deposits on the Blue Ridge directly above Nicholson and Corbin hollows was dependent upon hired-out slave labor. Bethany Veney (1889:33), born into slavery in Luray, penned a narrative of her life in which she recounts being sent up to Stony Man Mountain (the future location of the Skyland resort that was at the center of the park-creation movement):

The spur of the Blue Ridge, against which my little house leaned, was called “Stony Man”; and it was supposed to be full of copper. Some time ago, some Northern adventurers had set up an engine, in order to mine the copper and test its quality. But, for reasons which I had never understood, the project was abandoned and the men went home. They had built a small shanty on the ground, and I had lived with them to do their work. It had been a dreary experience to me, and I was thankful when it was over.

On the eastern side of the Blue Ridge, the situation was not dissimilar from the valley, in that enslaved people were predominantly held in small units and hired out for numerous different types of employment. In general, the numbers of enslaved persons were higher than the figures for the Shenandoah Valley, reflecting the greater influence of westward movement from the tidewater vs. the north-to-south pattern more common for the valley. In Madison County in 1800, of an overall population of 8,332, 3,436 were enslaved, while, in 1860, the U.S. federal census indicates 4,397 enslaved persons out of a population of 8,854. While small-scale slaveholding was the norm, there were still some sizable plantations. One that was close to the vicinity of Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley hollows was that of Thomas Shirley, who owned, at one time, over 48,000 ac., including lands in the hollows. His slave-based plantation operation was augmented by industrial concerns, including mills and distilleries (Lambert 1989:71). Not coincidentally, Shirley’s name appears on numerous documents related to hollow residents, including property deeds, wills, and chancery cases. But, as in the valley, 20th-century local historians downplayed slavery and, crucially, the continuing presence of African American communities. While Claude Lindsay Yowell, an early 20th-century Madison County historian, dedicated a short chapter in his 1926 A History of Madison County, Virginia to the “Colored People of Madison,” his perspective on the realities of enslavement was targeted toward a white readership and could hardly be termed critical: “[I]t seems evident that the majority of slave owners in Madison were not cruel,” and “[T]here was a great deal of friendship between master and slave” (Yowell 1926:166–167). Twentieth-century narratives collected from individuals formerly enslaved in nearby Rappahannock and Fauquier counties suggest a rather different reality. For example, Pine Bluff, Arkansas, resident Sonya Singfield (1941:166) noted that she had been “born in Washington, Virginia, right at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains,” and recalled that her “mother was sold when I was a babe in her arms. She was sold three times.” Painful insight into the experience of being a human commodity was conveyed by another Virginia-born Pine Bluff resident, 93-year-old Virginia Sims: “I was sold, put up on a stump just like you sell hogs to the highest speculator” (Sims 1941:163). Such a sight would have been familiar to William Hurt and his family, with their links to slavery and their lives as farmers in a slave-based agricultural economy.

Claude Yowell painted postbellum race relations in Madison County in terms as equally impossible as his view of master–slave relations: “[T]here is a warm personal friendship between the races” (Yowell 1926:171). Such uncritical sentiments were reiterated in a 1976 revision of Yowell’s study: “Few slaves deserted their masters during the Civil War. After emancipation, former masters tried to help slaves get established” (Davis 1977:15). In a rather uncritical understatement of the realities of postbellum life, author Margaret Davis blithely noted that “[a]fter receiving freedom, the former slaves sought homes, but unsettled conditions and lack of capital made this a somewhat difficult task” (Davis 1977:150). Reading between the lines of these official histories, it is possible to get a sense of the strategies employed by newly freed people to take control of their lives. Yowell, after celebrating the fact that freed people “have given up politics,” devotes much of his chapter on Madison’s African American community to the establishment of 15 Baptist churches in the postbellum period, itself an eloquent statement to African American community building in the face of political suppression. The first of those churches was organized in 1868, the same year that a school was established for freed people. While 11 of those postbellum churches are still active, the African American population of Madison County has since declined from nearly 50% of the population in 1860 to an estimated 9.3% of the county population (United States Census Bureau 2018), reflecting the impact of 20th-century population movement. The whiteness of Madison County today is too readily back projected to further deny past complexities and the experiences of the once-considerable black population; see Brandon (2013) for a parallel case study from the Ozarks.

Revision

I now offer a revised consideration of life in Nicholson, Weakley, and Corbin hollows. While the hollows may have been white spaces in the early 20th century, such was not the case in earlier centuries, including when William and Fannie/Frances Hurt adopted the Corbin children. As hinted at above, William Hurt was raised in a family that relied upon enslaved labor. The 1807 will of his uncle, James Hurt, listed seven enslaved people as his property: a woman named Judith and her daughter Tilda; Dafney and her son Moses; an adult man named Thomas; a boy called Thomas; and a girl named Elizabeth (Madison County Will Book 1807:177). William Hurt thus grew up around the institution of slavery in the form of these individuals whom he encountered on a regular and probably daily basis. Hurt’s will tells little about their lives, only revealing that Tilda, Dafney, Moses, the two Thomases, and Elizabeth accounted for the bulk of James Hurt’s wealth: $444.00 of the total value of $512.00, leaving just $68.00 worth of household and agricultural goods. Such an investment relative to the value of the remainder of Hurt’s estate suggests that he must have relied upon a financial return from hiring out their labor. Ultimately, James Hurt’s heirs benefited from the sale of the lives of the enslaved, even as the Hurts (including William) subsequently eschewed slaveholding. Wills and inventories like those of James Hurt chronicle control over people’s lives in violently dispassionate language. The silences in the record are loud. Tracing the fate of Tilda, Dafney, Moses, the two Thomases, and Elizabeth, whose lives were reduced to a set of numbers and casually enumerated between entries for “one smooth gun” and a “copper skillet,” is extremely challenging. Where did they go after they were sold to as-yet-undiscovered buyer(s)? The documentary record that I once found so exciting and helpful in tracing the Hurts, Corbins, Nicholsons, and other white families betrayed its true character as an instrument of racial oppression.

Turning back to the year 1818, the same year that the Hurts took in the 10 Corbin children, inequality as well as diversity in the hollows is further illuminated. A few months before William and Fannie/Frances Corbin married, a prominent neighbor, James Ward, died. At the time, Ward owned and occupied a property consisting of 80 ac. in the lower end of Nicholson Hollow, a few miles from the Hurt farm. In Ward’s 1818 will, the property was left to his wife Nancy and daughter Margery or Margaret Berry. Ward received “part of the tract I now live on, including the dwelling house,” while Berry received “the lower part of my land Beginning five poles below the field and thence extending to the end of the tract adjoining to William Weakley’s line” (Madison County Will Book 1818:444). Ward’s total movable property was assessed at $2,210.79, and an inventory indicates that 81% of that figure was bound up in the lives of five enslaved people: “Lucy her two children Cealy and Lewis” and two boys, “Jack and Frank.” These individuals were valued at $1,800, and their lives split between new owners: Ward’s widow and his married daughter. Their work provided the funds needed for Ward to fill his home with various chests, bedsteads, and chairs, and provided him the leisure time to read his “parcel of books.” Ward’s time clock presumably ordered not only his hours, but those of his involuntary workforce. Cattle and hogs were raised on the land, cotton and flax processed, liquor distilled, and a smithy operated, giving a sense of the labor performed by Lucy, the children, hired slaves, and apprentices. Ward’s inventory tells us nothing, however, about the ways in which Lucy and the children navigated the realities of their own disenfranchisement (Madison County Will Book 1818:444).

In 1997, I conducted limited test excavations in the location of Ward’s former dwelling house, henceforward referred to by its internal site designation of 80DG. I was initially attracted to 80DG because it was associated with the first residency of the Nicholson family in their eponymous hollow. In 1799, John and Anne Nicholson purchased 170 ac. in the hollow from the original patentee, Mark Finks (Madison County Deed Book 1799). Like many archaeologists, I fell prey to the need to find the “oldest” and to archaeologically trace the family for whom I had developed an affinity through immersion in their daily lives in the hollow from the 18th until the early 20th centuries. At the time of park establishment, the site associated with Ward and the early Nicholsons (80DG) was owned by Victoria and William “Buddy” Nicholson. There they occupied a 20 ac. farm sold to the Virginia Commission on Conservation and Development (the state body responsible for surveying and acquiring park lands for donation to the federal government) that was part of a 40 ac. parcel deeded by John and Anne Nicholson to their son Shadrach in 1805 (Madison County Deed Book 1805). Although both Buddy and Victoria Nicholson were direct descendants of the initial Nicholson settlers, their residency was not the result of an unbroken family occupation of the farm. In fact, within a year of acquiring the 40 ac. parcel, Shadrach Nicholson sold the land to William Berry, who sold the property to James Ward in 1815 (Madison County Deed Book 1815). The slaveholding Ward, who also owned the Nethers Mill that still stands just outside Nicholson Hollow, apparently moved into the hollow at this time.

As recorded in the 1990s, 80DG contains traces of two log dwellings, two stone-lined cellars, a barn, a stone-lined well, and a cemetery, albeit all in a ramshackle condition (Fig. 3). Park-era photographs clearly detailed the presence of two log dwellings: a sizable six-room log-and-frame house with double chimneys and a stone foundation and a small single-room log dwelling. Excavations in 1997 recovered late 18th-century materials (creamware and a snuff-bottle fragment) from the smaller structure. These finds gave some weight to my hypothesis that the small log structure at 80DG had been built and inhabited when John and Anne Nicholson acquired the land and when their son Shadrach was in residence. I further surmised that the more commodious log, stone, frame farmhouse was first constructed during the Ward ownership, given Ward’s relative wealth. The smaller dwelling, then, makes a plausible candidate for housing Lucy, Cealy, Lewis, Jack, and Frank (Fig. 3).

So, what is most important about that small log structure? that it housed the first Nicholsons, long memorialized and commemorated by scholars (Perdue and Martin-Perdue 1979–1980; Horning 2004) or that it housed an enslaved woman, her two children, and two young boys (about whom the documentary record tells us next to nothing)? I know my answer now and take responsibility for my answer then. At the time, I certainly did recognize the importance of the association with Lucy, her children, and the two boys, and I made a point of raising it even when I knew the members of the park-descendant community were generally uncomfortable with discussing that aspect of their history. But I worried about positionality and rights, acutely conscious that, not being of the African diaspora, it was not ethically appropriate for me to be the one to speak for the lives of Lucy and her children. It was more straightforward to address a story of white poverty and marginalization; a story that I could “own” on a more personal level. Given the realities of white privilege, structural inequality, and the need to decolonize archaeological practice, I continue to be very uneasy about my voice being employed to tell a story of African America, particularly one that is out of step with more recent trends that shift emphasis from the period of enslavement to examining the myriad ways in which African American individuals shaped their lives and structured diverse communities in the context of post-emancipation discrimination (Singleton 2010; Barnes 2011; Mahoney 2013). But, at the same time, I have encountered and uncovered shreds of the lives of Lucy, Cealy, Lewis, Jack, and Frank, and so I also have a responsibility to share that information. My own subject position provides another dimension to this process. I cannot and should not speak for those who endured enslavement, but I can speak of them in the present to audiences who may otherwise be unaware or even resistant to the reality of an African American imprint on Blue Ridge history. In this manner I follow both the lead of Carol McDavid (2002, 2011) in engaging with white audiences and the advice of Whitney Battle-Baptiste in working toward “a proactive approach to the study of captive African people” (Battle-Baptiste 2011:22).

Such conversations must include consideration of the manner in which race-based structural inequalities permeate aspects of everyone’s lives. While the documentary record indicates that the Nicholson clan themselves were never slaveholders, they (along with their white neighbors) benefited from the system by the clear advantage of being white and free, as well as having access to hired enslaved laborers. At the same time, members of the Nicholson family, as non-slaveholders, would have also understood their position within the white hierarchy. The unequal relationship between the Wards and the Nicholsons is evident in an 1810 indenture, whereby William Nicholson (son of John and Anne Nicholson) delivered his son William to Ward, who, in exchange for five years of the young William’s labor, was to “bestow him with a liberal education such as befitting a poor man’s son” (Madison County Will Book 1810). Far from the kind of egalitarian, self-sufficient mountain lifestyle imagined by many, especially the descendants of the displaced denied their own opportunity to live on the mountain, community life across the hollows was characterized by hierarchy, inequality, and constant negotiations both within and across kin groups (Horning 2000a:221–222). Family and community membership could be conditional, as illustrated by Montella Jones’s apparent ejection from the wider Hurt network following the deaths of Israel and Susan Hurt. At the same time, hollow dwellers were bound to one another via proximity as well as interdependency. But those interdependencies, as illustrated by the William Nicholson indenture, could be uneven and unequal. William presumably worked alongside the enslaved woman Lucy in the service of Ward’s household, further cementing his lower status. However, while William may have been a poor man’s son, he was promised the education and the freedom denied to Lucy, her children Cealy and Lewis, and to the two boys Jack and Frank.

It is important also to note that, as a slaveholder in Nicholson Hollow, James Ward was not anomalous. One of the signatories to William Nicholson’s indenture was Benjamin Lillard the Younger, scion of a slaveholding family. In 1787, Lillard acquired 487 ac. along the Hughes River in Nicholson Hollow (Northern Neck Land Grants 1787). In 1821, the personal estate of Benjamin Lillard the Younger was appraised at a value of $2,449.34 (Madison County Will 1821). Listed immediately after the livestock and before a variety of farming implements are three enslaved individuals: Simon, Betty, and Sharlot—man, woman, and girl––possibly representing a nuclear family. Simon and Betty had long been held by the Lillard family, as two persons of the same name were left to Heziah Lillard in her husband James’s 1804 will, with the proviso that ownership of the couple revert to Benjamin Lillard following his mother’s death. The monetary value of these enslaved individuals, totaling $565.00, represents nearly one-quarter of Benjamin Lillard’s entire estate, assuring him—like neighbor James Ward—of relative social standing in the slave-based agricultural society of antebellum Virginia.

The written record that so intentionally frustrates efforts to trace the African American residents of the hollows provides insight into the economic stratification found within the white kinship groups, as played out in grim detail in the chancery records that record the unpleasant family wrangling over the orphaned Susan Frances Hurt’s inheritance. Slaveholding and non-slaveholding families were also often one and the same. Some members of the Hurt, Lillard, and Ward families held slaves; some did not. Attitudes toward the institution of slavery and the politics of the Civil War divided families in the hollows much as they did elsewhere in the upper South and particularly western Virginia. Two years after Montella Jones left Susan Frances Hurt behind in the grudging care of her aunt, he enlisted in Company E of the Twelfth West Virginia Infantry and fought for the Union. Back in the hollows, (non-slaveholding) Nicholson men joined neighbors from the (formerly slaveholding) Hurt and Lillard families in the Confederate forces. Among the many African Americans from the region who fought in the war can be found several with the surname of Berry. Madison County resident George Berry served in the U.S. Colored Infantry, while a George Berry from Rappahannock County served in Company E of the Thirteenth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, and David Berry from Page County enlisted in the Fifty-third U.S. Colored Infantry. Could any of those men be linked with Margery Ward Berry, who inherited people’s lives in her father James Ward will in 1818 and later appears as a slaveholder in Page County?

After the war, some of the Shirley lands on Robertson Mountain, which separates Nicholson and Weakley hollows, were acquired by two former Union soldiers from Maine, Edward and William Dyer. Whatever tensions must have accompanied their entrée into the local community seem to have dissipated, with the Dyer family becoming well embedded in the Weakey Hollow/Old Rag community by the time of park establishment. While the last documented African American residents of the three hollows were Simon, Betty, and Sharlot in the household of Benjamin Lillard the Younger in 1821, no border separated the future park lands around Old Rag Mountain from the rest of Madison County, and elsewhere African Americans remained on lands that would become the park. Hollow residents would have been aware of and some participants in the 1832 Madison County evenly split vote over abolition (Davis 1977:296). The economic challenges, political upheavals, and racist violence of the Reconstruction era reverberated up the slopes, such as the unsolved 1868 murder of a Rappahannock County African American man, Arthur Lee (Freedmen’s Bureau Online 1868). White hollow dwellers traveling into local villages and to the county seat of Madison not only witnessed segregated spaces, but, by virtue of their whiteness and irrespective of their economic status, they were implicated in the maintenance and reification of race-based discriminatory practices. At the same time, even whiteness proved insufficient protection against the momentum of the park-creation movement and the manner in which it capitalized on the economic marginalization of many mountain residents.

Concluding Thoughts

Lessons learned: by approaching the Blue Ridge principally from the standpoint of the early 20th-century experiences of the displaced, the deeper, more racially diverse history of the Blue Ridge region was obscured from the start. The complex kinship webs that tied Blue Ridge and piedmont families were artificially, if inadvertently, severed by the scope of the archaeological project that was confined within park boundaries. I employed the archaeological record from the hollows in the interest of deconstructing the inaccurate portrayals of park area families in acknowledgment of and deference to the concerns of the displaced and their descendants. The hurt and trauma experienced by those who lost their homes to the park is undeniable and worthy of continued attention and acknowledgment, as underscored by the recent erection of monuments to the displaced spearheaded by a member of today’s Lillard family (Brooks 2015; Lohman 2017). But there is a larger context that also must be acknowledged, that is inclusive of other stories of exploitation, displacement, and inequality. Much more research remains to be done to piece together the whole story more properly and thoroughly, and inclusive of the African Americans whose lives were lived out, in whole or part, on the mountain. Their experiences and those of their descendants need to be recognized as a significant element in the narratives of injustices and displacement in the Shenandoah National Park vicinity. The descendants of the individuals once enslaved by the Wards, Hurts, Berrys, and Lillards are out there, perhaps still in the same region. My archival awakenings may just be chasing after what they already know in their family histories and legends, but maybe not. My knowledge of physical places where enslaved people lived out their lives within what is now Shenandoah National Park may be of real value to people in the present seeking a connection to their ancestors, to the lives those ancestors built, and the fundamental contributions they made to the historical settlement of the Virginia Blue Ridge. The new questions and perspectives that could be brought by descendants have the potential to guide future research into this critical history.

There is a parallel need to acknowledge and engage with the descendants of the indigenous people who shaped the Blue Ridge landscape acquired by 18th-century settlers. Their stories, at this point in time, seem even more elusive than those of Blue Ridge African Americans insofar as all available evidence suggests that, by the 18th century, the lands around Old Rag Mountain had been vacated by the Siouan Manahoac peoples, with the Blue Ridge serving mainly as seasonal hunting territory for the Shawnee, Iroquois, and Susquehannock (Egloff and Woodward 1992; Nash 2009). But that elusiveness is likely illusory, as witnessed by the ongoing presence of the Siouan Monacan people just to the south of the park, in Amherst County. Declared extinct in those same Madison County history books that proffered self-serving views of happy slaves and benevolent masters (Yowell 1926; Davis 1977), the Monacan attained federal recognition in 2017. The extent to which the Monacan and the Manahoac may be related remains a matter of debate. The key question that remains, as expressed by Carole Nash (2009:391), is “[W]hat historical processes made the Manahoac almost virtually invisible in the documentary record of the post-Contact period?” The answer lies partially in the same frames of mind that can look past the considerable evidence for an African American presence in the Blue Ridge: because that is not the story that has been chosen for telling.

Historical archaeology’s disciplinary conceit rests on the belief that access to a multitude of sources inevitably leads to the construction of more inclusive narratives. But, not if we archaeologists rely too heavily on records written in support of dominant white society and, especially, if we fail to critically acknowledge the impact of structural inequities on the discipline itself. In particular, revisiting, reflecting on, and revising our own scholarship, and being willing to address our own culpabilities, is a necessary step in developing a critical, self-reflexive, and decolonizing practice of historical archaeology.

References

Barnes, Jodi 2011 An Archaeology of Community Life: Appalachia, 1865–1920. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 15(4):669–706.

Battle-Baptiste, Whitney 2011 Black Feminist Archaeology. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Brandon, Jamie C. 2013 Reversing the Narrative of Hillbilly History: A Case Study Using Archaeology at Van Winkle’s Mill in the Arkansas Ozarks. Historical Archaeology 47(3):36–51.

Brooks, Gracie Hart 2015 Permanent Memorial to Those Displaced by National Park Is Going up in Madison, 24 September. The Daily Progress <https://www.dailyprogress.com/news/local/permanent-memorial-to-those-displaced-by-national-park-is-going/article_eed9b40a-6329-11e5-b27b-fbf922c267b4.html>. Accessed 19 February 2021.

Buttler, Henry H. 1941 Ex-Slave Stories (Texas): Henry H. Buttler. In Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 1, pp. 179–181. Manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Library of Congress <https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.161/?sp=186>. Accessed 11 March 2021.

Davis, Margaret 1977 Madison County Virginia: A Revised History. Madison County Board of Supervisors, Madison, VA.

Denkler, Ann 2001 Sustaining Identity, Recapturing Heritage: Exploring Issues of Public History, Tourism, and Race in a Southern Rural Town. Doctoral dissertation, Department of American Studies, University of Maryland, College Park. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Dunaway, Wilma A. 1995 The First American Frontier: Transition to Capitalism in Southern Appalachia, 1700–1860. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Ebert, Rebecca A. 1986 A Window on the Valley: A Study of the Free Black Community of Winchester and Frederick County, Virginia 1785–1860. Master’s thesis, Department of History, University of Maryland, College Park.

Egloff, Keith, and Deborah Woodward 1992 First People: The Early Indians of Virginia. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Ellis, Sarah E. 2011 Mount Vernon Furnace (44RM203): The Industrial Archaeology of Resource Capitalism in the Virginia Blue Ridge. Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Virginia 66(1):1–10.

Engle, Reed 1998a Shenandoah––Laboratory for Change? Cultural Resource Management 21(1):34–35.

Engle, Reed 1998b Shenandoah National Park: A Historical Overview. Cultural Resource Management 21(1):7–10.

Engle, Reed, and Caroline Janney 1997 A Database of Shenandoah National Park Land Records. Shenandoah National Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Luray, VA.

Eslinger, Ellen 2000 “Sable Spectres on Missions of Evil”: Free Blacks of Antebellum Rockbridge County, Virginia. In After the Backcountry: Nineteenth-Century Life in the Valley of Virginia, Kenneth E. Koons and Warren R. Hofstra, editors, pp. 145–168. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Freedmen’s Bureau Online 1868 Case 72. Register of Outrages Committed on Freedmen Pt. 4, Virginia, The Freedmen’s Bureau Online <https://freedmensbureau.com/virginia/registeroutrages4.htm>. Accessed 14 April 2021.

Gregg, Sara M. 2010 Managing the Mountains: Land Use Planning, the New Deal, and the Creation of a Federal Landscape in Appalachia. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Hofstra, Warren 2004 The Planting of New Virginia: Settlement and Landscape in the Shenandoah Valley. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Horning, Audrey J. 1998 “Almost Untouched”: Recognizing, Recording and Preserving the Archaeological Heritage of a Natural Park. CRM: Cultural Resource Management 21(1):31–33.

Horning, Audrey J. 1999 In Search of a ‘Hollow Ethnicity’: Archaeological Explorations of Rural Mountain Settlement. In Current Perspectives on Ethnicity in Historical Archaeology, M. Franklin and G. Fesler, editors, pp. 121–138. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

Horning, Audrey J. 2000a Archaeological Considerations of “Appalachian” Identity: Community-Based Archaeology in the Blue Ridge Mountains. In The Archaeology of Communities: A New World Perspective, Marcello Canuto and Jason Yaeger, editors, pp. 210–230. Routledge Press, New York, NY.

Horning, Audrey J. 2000b Beyond the Valley: Interaction, Image, and Identity in the Virginia Blue Ridge. In After the Backcountry: Nineteenth-Century Life in the Valley of Virginia, Kenneth E. Koons and Warren R. Hofstra, editors, pp. 145–168. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Horning, Audrey J. 2001 Of Saints and Sinners: Landscapes of the Old and New South. In Contested Memories and the Making of the American Landscape, Paul Shackel, editor, pp. 21–46. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Horning, Audrey J. 2002 Myth, Migration and Material Culture: Archaeology and Ulster Influence on Appalachia. Historical Archaeology 36(4):129–149.

Horning, Audrey J. 2004 In the Shadow of Ragged Mountain: Historical Archaeology of Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley Hollow. Shenandoah National Park Association, Luray, VA.

Horning, Audrey J. 2007 Overview and Assessment of Cultural Resources in Shenandoah National Park. Report to National Park Service, Northeast Region, Valley Forge, PA, from Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

Horning, Audrey 2019 Removal and Remembering: Archaeology and the Legacies of Displacement in Southern Appalachia. In Archaeologies of Displacement, Terrance Weik, editor, pp. 127–156. University of Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Inscoe, John C. 1994 Race and Racism in Nineteenth-Century Southern Appalachia. In Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century, Mary Beth Pudup, Dwight B. Billings, and Altina Waller, editors, pp. 103–131. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Inscoe, John C. (editor) 2001 Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington.

Krumenaker, Bob 1998 Cultural Resource Management at Shenandoah: It Didn’t Come Naturally. CRM: Cultural Resource Management 21(1):4–6.

Lambert, Darwin 1989 The Undying Past of Shenandoah National Park. Shenandoah Natural History Association, Luray, VA.

Lewis, Ronald L. 1979 Coal, Iron, and Slaves: Industrial Slavery in Maryland and Virginia, 1715–1865. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

Lohman, Bill 2017 New Monuments Honor People Forced from Their Homes to Make Way for Shenandoah National Park, 11 March. Richmond Times-Dispatch <https://www.richmond.com/life/new-monuments-honor-people-forced-from-their-homes-to-make/article_4bf818f6-13c3-5973-993d-9e22bb4cba4b.html>. Accessed 19 February 2021.

Lombardo, Paul 2008 Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck vs. Bell. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Madison County Chancery Orders 1887 Guardians of Frances Hurt v. Frances Hurt. Madison County Chancery Orders 52:1–210, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA. Virginia Memory: Library of Virginia <https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=113-1887-052>. Accessed 14 April 2021.

Madison County Chancery Records 1818 Zachariah Shirley v. Administrator of the Estate of Thomas Shirley. File 13, Folder 7, Shirley Files, Madison County Chancery Records, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Deed Book 1799 Mark Finks to John and Anne Nicholson, 27 June. Madison County Deed Book 2:294, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Deed Book 1805 John and Anne Nicholson to Shadrach Nicholson, 7 March. Madison County Deed Book 4:128, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1807 Last Will and Testament of James Hurt, 29 December. Madison County Will Book 2:177–178, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Deed Book 1815 William and Jemimah Berry to James Ward, 23 May. Madison County Deed Book 4:452, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1810 Indenture of William Nicholson to James Ward, 10 May. Madison County Will Book 2:251, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1818 Last Will and Testament of James Ward, proved 10 April 1819. Madison County Will Book 3:442–445, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1821 Last Will and Testament of Benjamin Lillard. Madison County Will Book 4:90, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1834 Last Will and Testament of William Hurt, 22 July, proved 22 May 1843. Madison County Will Book 7:302–303, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Madison County Will Book 1858 Last Will and Testament of Israel Hurt and Inventory of Possessions. Madison County Will Book 11:61,103,191, Madison County Courthouse Clerk’s Record Room, Madison, VA.

Mahoney, Shannon 2013 Community Building after Emancipation: An Anthropological Study of Charles Corner Virginia 1862–1922. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

McDavid, Carol 2002 Archaeologies that Hurt; Descendants that Matter: A Pragmatic Approach to Collaboration in the Public Interpretation of African American Archaeology. World Archaeology 34(2):303–314.

McDavid, Carol 2011 From “Public Archaeologist” to “Public Intellectual”: Seeking Engagement Opportunities Outside Traditional Archaeological Arenas. Historical Archaeology 45(1):25–32.

Mitchell, Robert D. 1972 The Shenandoah Valley Frontier. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 62(3):461–486.

Nash, Carole 2009 Modeling Uplands: Landscape and Prehistoric Native American Settlement Archaeology in the Virginia Blue Ridge Foothills. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Northern Neck Land Grants 1787 James McDaniel and William Duff to Benjamin Lillard. Northern Neck Land Grants Book 10, 1795–1797, pp. 583–584, Archives of the Library of Virginia, Richmond.

Perdue, Charles L., Jr., and Nancy Martin-Perdue 1979–1980 Appalachian Fables and Facts: A Case Study of the Shenandoah National Park Removals. Appalachian Journal 7(1&2):84–104.

Powell, Katrina 2007 The Anguish of Displacement: The Politics of Literacy in the Letters of Mountain Families in Shenandoah National Park. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Powell, Katrina 2009 “Answer at Once”: Letters of Mountain Families in Shenandoah National Park, 1934–1938. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Powell, Katrina 2013 Converging Crises: Rhetorical Construction of Eugenics and the Public Child. JAC [Journal of Advanced Composition] 33(3&4):455–485.

Rothstein, Arthur 1935 Interior of Postmaster Brown's Home at Old Rag. Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, October. Photo, Digital ID: fsa 8b26672, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress Washington, DC. Library of Congress <https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017758903/>. Accessed 22 February 2021.

Sherman, Mandel, and Thomas Henry 1933 Hollow Folk. Thomas Crowell and Son, New York, NY.

Sherman, Mandel, and Cora Key 1929 Report of a Preliminary Psychological and Sociological Survey of Corbin Hollow, Va., 11 October. Manuscript, Misc. Correspondence 1929, Lou Henry Hoover Papers, White House General Files, Hoover Library, West Branch, IA.

Sherman, Mandel, and Cora Key 1932 The Intelligence of Isolated Mountain Children. Child Development Magazine 3(4):279–290.

Silber, Nina 2001 “What Does America Need So Much as Americans?”: Race and Northern Reconciliation with the Southern Appalachians, 1870–1900. In Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation, John C. Inscoe, editor, pp. 245–258. University of Kentucky Press, Lexington.

Sims, Virginia 1941 Interviewer: Bernice Bowden, Person Interviewed: Virginia Sims. In Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938, Vol. 2, Arkansas, Part 6, pp. 163–165. Manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Library of Congress <https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.026/?sp=168>. Accessed 19 February 2021.

Singfield, Sonya 1941 Interviewer: Mrs. Bernice Bowden, Person Interviewed: Sonya Singfield. In Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938, Vol. 2, Arkansas, Part 6, p. 166. Manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Library of Congress <https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.026/?sp=171>. Accessed 22 February 2021.

Singleton, Theresa 2010 Liberation and Emancipation: Constructing a Postcolonial Archaeology of the African Diaspora. In Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology, Jane Lydon and Uzma Rizvi, editors, pp. 185–198. Springer, New York, NY.

Sizer, Miriam 1932 Tabulations: Five Mountain Hollows. Manuscript, Shenandoah National Park File 204, Central Files, Record Group 79, National Archives, Laurel, MD.

Starobin, Robert 1968 Disciplining Industrial Slaves in the Old South. Journal of Negro History 53(2):111–128.

State Commission on Conservation and Development Land Records 1869–1995 Augusta County Land Tract 45, John West Estate. Box 10, Folder 59, Shenandoah National Park Archives, Luray, VA.

Steere, Edward 1935 Report on Preservation of Structures, 1 June. Manuscript, Shenandoah National Park Resource Management Records, Shenandoah National Park Archives, Luray, VA.

United States Census Bureau 2018 Quick Facts: Madison County, Virginia. United States Census Bureau <https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/madisoncountyvirginia/PST045217>. Accessed 13 November 2018

U.S. Bureau of the Census 1810 Culpeper County, Virginia. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC. Ancestry <https://www.ancestry.com>. Accessed 9 October 2018.

U.S. Bureau of the Census 1820 Culpeper County, Virginia. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC. Ancestry <https://www.ancestry.com>. Accessed 9 October 2018.

U.S. Bureau of the Census 1860a Frederick County, Virginia. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC. Ancestry <https://www.ancestry.com>. Accessed 7 November 2018.

U.S. Bureau of the Census 1860b Madison County, Virginia. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC. Ancestry <https://www.ancestry.com>. Accessed 7 November 2018.

Veney, Bethany 1889 The Narrative of Bethany Veney: A Slave Woman. N.p., Worcester, MA.

Vogt, John, and T. William Kethley, Jr. 2011 Madison County Marriages 1792–1850. Iberian, Athens, GA.

Yowell, Claude Lindsay 1926 A History of Madison County Virginia. Shenandoah Publishing House, Strasburg, VA.

Wayland, John W. 1989 Twenty-Five Chapters on the Shenandoah Valley, 2nd edition. C. J. Carrier Company, Harrisonburg, VA.

Zaborney, John Joseph 1997 Slaves for Rent: Slave Hiring in Virginia. Doctoral dissertation, Department of History, University of Maine, New Brunswick. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Acknowledgments:

I am grateful to Anna Agbe-Davies and Rich Veit for reviewing drafts of this article and providing me with valuable advice for clarifying my arguments. I am very grateful to Chardé Reid for her constructive comments and for the conversations that initially led me to write this article, and to Chandler Fitzsimons for her thoughtful reflections on the entanglement of race and 20th-century displacement. The original research in the park would not have happened without the support of Marley Brown, David Orr, and Reed Engle. I would have benefited from Reed’s perspective on this article, and I dedicate it to his memory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Horning, A. Reflections on Research: Race and the Virginia Blue Ridge. Hist Arch 56, 32–48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-021-00295-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-021-00295-3