Abstract

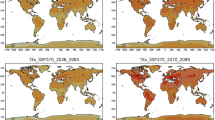

The XCO2 concentration across climate type remains largely unexplored. This paper examined carbon concentration across climate types in India using Level 2 data (378,050 sample points) of column-averaged CO2 concentrations (XCO2) that were collected from the orbiting carbon observatory (OCO-2) in September 2014 to August 2015. Temperate climate ranks first among climate types in terms of energy demand and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions due to continued intensive urbanization. However, urbanization in temperate climate was not the most important predictor of higher XCO2 concentration in India. On the contrary, the annual XCO2 mean concentration in tropical climate was higher than annual XCO2 mean concentration in temperate climate. In contrast to the typical theory, temperate climate were not a dominant determining factor upon dense XCO2 concentration. A clear verification has been made for the typical theory for CO2 concentration increased across global urbanization. The individual climate types are found to be more appropriate in explaining global CO2 concentration, rather than urban location. It was demonstrated that the climate types could be used effectively as an indicator to global CO2 concentrations since the OCO-2 signature of 378,050 sample points can present objective area-wide evidences as a basis for regional climate comparisons. It is anticipated that this research output could be used as a valuable reference to a strong theoretical basis to compare carbon concentrations across climate types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

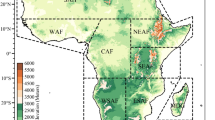

China has 11 climate zones. Chile, which is expected to include various climate zones in the long territory from the north to the south, includes only eight climate zones [18]. Climate Zone Description: As/Aw (Tropical savanna climate), BSh (Steppe climate), BWh (Desert climate), Csa (Mediterranean climate), Cwa (Humid subtropical climate), Cwb (Subtropical highland climate).

The retrieval algorithm is to derive estimates of the column-averaged atmospheric CO2 dry air mole fraction, XCO2, and other Level 2 data products from the returned spectra by the OCO-2. The ratio of the column abundances of CO2 to the column abundance of dry air is the main purpose of retrieval algorithm.

TCCON is affiliated with the Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Composition Change Infrared Working Group (NDACC-IRWG) and the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) programme. The Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) programme of WMO is a partnership involving the Members of WMO, contributing networks and collaborating organizations and bodies which provides reliable scientific data and information on the chemical composition of the atmosphere, its natural and anthropogenic change, and helps to improve the understanding of interactions between the atmosphere, the oceans and the biosphere. TCCON is a network of ground-based Fourier Transform Spectrometers recording direct solar spectra in the near-infrared spectral region. From these spectra, accurate and precise column-averaged abundance of CO2, CH4, N2O, HF, CO, H2O, and HDO are retrieved. TCCON provides an essential validation resource for the Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO), Sciamachy, and GOSAT.

References

Jacobson, M. Z. (2005). Correction to “Control of fossil-fuel particulate black carbon and organic matter, possibly the most effective method of slowing global warming”. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110, D14105. doi:10.1029/2005JD005888

Kumar, K. R., Revadekar, J. V., & Tiwari, Y. K. (2014). AIRS retrieved CO2 and its association with climatic parameters over India during 2004–2011. Science of the Total Environment, 476–477, 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.118.

Tiwari, Y. K., Revadekar, J. V., & Kumar, K. R. (2013). Variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide and its association with rainfall and vegetation over India. Atmospheric Environment, 68, 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.11.040.

Ganguly, D., Dey, M., Chowdhury, C., Pattnaik, A. A., Sahu, B. K., & Jana, T. K. (2011). Coupled micrometeorological and biological processes on atmospheric CO2 concentrations at the land–ocean boundary, NE coast of India. Atmospheric Environment, 45(23), 3903–3910. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.08.047.

Strachan, I. B. (2003). World survey of climatology, general climatology 1C: Classification of climates: O.M. Essenwanger, Elsevier, 113 pp., 2001, US$ 129.50, ISBN 0 444 88278 2. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 115(3–4), 231–232. doi:10.1016/S0168-1923(02)00230-7.

Dlugokencky, E. J., Lang, P. M., Mund, J. W., Crotwell, A. M., Crotwell, M. J., & Thoning, K. W. (2016). Atmospheric carbon dioxide dry air mole fractions from the NOAA ESRL carbon cycle cooperative global air sampling network, 1968–2015. Version: 2016-08-30. ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/co2/flask/surface/.

Reuter, M., Buchwitz, M., Schneising, O., Heymann, J., Bovensmann, H., & Burrows, J. P. A. (2010). Method for improved SCIAMACHY CO2 retrieval in the presence of optically thin clouds. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 3(1), 209–232.

Guo, M., Wang, X. F., Li, J., Yi, K. P., Zhong, G. S., Wang, H. M., et al. (2013). Spatial distribution of greenhouse gas concentrations in arid and semi-arid regions: A case study in East Asia. Journal of Arid Environments, 91, 119–128. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2013.01.001.

Shim, C. S., Lee, J. S., & Wang, Y. (2013). Effect of continental sources and sinks on the seasonal and latitudinal gradient of atmospheric carbon dioxide over East Asia. Atmospheric Environment, 79, 853–860. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.07.055.

Tiwari, Y. K., Revadekar, J. V., & Kumar, K. R. (2014). Anomalous features of mid-tropospheric CO2 during indian summer monsoon drought years. Atmospheric Environment, 99, 94–103. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.09.060.

Hammerling, D. M., Michalak, A. M., & Kawa, S. R. (2012). Mapping of CO2 at high spatiotemporal resolution using satellite observations: Global distributions from OCO-2. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 117, D06306. doi:10.1029/2011JD017015

Thompson, D. R., Benner, D. C., Brown, L. R., Crisp, D., Devi, V. M., Jiang, Y., et al. (2012). Atmospheric validation of high accuracy CO2 absorption coefficients for the OCO-2 mission. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 113(17), 2265–2276. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2012.05.021.

Frankenberg, C., Pollock, R., Lee, R. A. M., Rosenberg, R., Blavier, J.-F., Crisp, D., et al. (2015). The orbiting carbon observatory (OCO-2): Spectrometer performance evaluation using pre-launch direct sun measurements. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 8, 301–313.

Hwang, Y., & Um, J.-S. (2016). Performance evaluation of OCO-2 XCO2 signatures in exploring casual relationship between CO2 emission and land cover. Spatial Information Research, 24(4), 451–461. doi:10.1007/s41324-016-0044-8.

Hwang, Y., & Um, J.-S. (2016). Evaluating co-relationship between OCO-2 XCO2 and in situ CO2 measured with portable equipment in Seoul. Spatial Information Research,. doi:10.1007/s41324-016-0053-7.

The World Bank Group. (2015). http://sdwebx.worldbank.org/climateportal/index.cfm?page=country_historical_climate&ThisRegion=Asia&ThisCCode=IND. Accessed 13 Jan 2015.

Ministry of Environment and Forests (edited by Pande, K. & Arora S.). (2014). India's Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity 2014. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. New Delhi, India, https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/in/in-nr-05-en.pdf.

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B., & Rubel, F. (2006). World map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 15(3), 259–263.

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., & McMahon, T. A. (2007). Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 11(5), 1633–1644.

Köppen, W. (1936). Das geographische System der Klimate. In W. Köppen & R. Geiger (Eds.), Handbuch der Klimatologie (Vol. 1(C), pp. 1–44). Berlin: Verlag von Gebrüder Borntraeger.

Russell, R. J. (1931). Dry climates of the United States: I climatic map. University of California Publications in Geography, 5, 1–41.

Wilcock, A. A. (1968). Köppen after fifty years. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 58(1), 12–28.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology. (2014). OCO-2 level 2 full physics retrieval algorithm theoretical basis, version 2.0 REV 0. Washington, D.C: NASA.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology. (2015). Orbiting carbon observatory-2 (OCO-2) data product user’s guide, operational L1 and L2 data, versions 6 and 6R, version D. Washington, D.C: NASA.

Kuai, L., Wunch, D., Shia, R.-L., Connor, B., Miller, C., & Yung, Y. (2012). Vertically constrained CO2 retrievals from TCCON measurements. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, 113(14), 1753–1761. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2012.04.024.

Taylor, T. E., O'Dell, C. W., Partain, P. T., Cronk, H. Q., Nelson, R. R., Rosenthal, E. J. et al. (2016). Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) cloud screening algorithms: validation against collocated MODIS and CALIOP data. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 9(3), 973.

Singh, R. B., Janmaijaya, M., Dhaka, S. K., & Kumar, V. (2015). Study on the association of green house gas (CO2) with monsoon rainfall using AIRS and TRMM satellite observations. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 89–90, 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2015.04.004.

Prasad, P., Rastogi, S., & Singh, R. P. (2014). Study of satellite retrieved CO2 and CH4 concentration over India. Advances in Space Research, 54(9), 1933–1940. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2014.07.021.

Tadić, J. M., & Michalak, A. M. (2016). On the effect of spatial variability and support on validation of remote sensing observations of CO 2. Atmospheric Environment, 132, 309–316.

Skymet. (2015). http://www.skymetweather.com/meteosat/weather-satellite-images-of-india. Accessed 13 Jan 2015.

NOAA. (2015). ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/products/trends/co2/co2_mm_gl.txt. Assessed 25 Jan 2016.

Cho, H. M., Lim, Y. K., Kim, J. W., Kim, J. K., & Kim, J. Y. (2000). The features of global atmospheric CO2 distribution pattern. Asia-Pacific Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 36(2), 167–178.

York, R., Rosa, E. A., & Dietz, T. (2003). STIRPAT, IPAT and ImPACT: Analytic tools for unpacking the driving forces of environmental impacts. Ecological Economics, 46(3), 351–365. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(03)00188-5.

Cole, M. A., & Neumayer, E. (2004). Examining the impact of demographic factors on air pollution. Population and Environment, 26(1), 5–21. doi:10.1023/B:POEN.0000039950.85422.eb.

Bernstein, L., Bosch, P., Canziani, O., Chen, Z., Christ, R., Davidson, O., et al. (2007). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. In R. K. Pachauri, & A. Reisinger (Eds.). Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva: IPCC.

International energy agency. (2008). World energy outlook 2008. Paris: OECD/IEA.

UN. (2006). World urbanization prospects 2005. http://esa.un.org/unup. New York.

United nations, department of economic and social affairs, population division (2015). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 Revision, (ST/ESA/SER.A/366). New York.

Cohen, J. E., & Small, C. (1998). Hypsographic demography: The distribution of human population by altitude. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(24), 14009–14014. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14009.

IMF. (2015). World economic outlook database-October 2015. Accessed 18 Oct 2015.

Chandramouli, C. (2011). States census 2011. http://www.census2011.co.in/states.php. Accessed 13 Jan 2016.

McKnight, T. L., & Hess, D. (2002). Physical geography: A landscape appreciation (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Schimel, D. E. A. (1996). Climate change 1995: The science of climate change. Contribution of working group I to the second assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Prentice, I. C., Farquhar, G. D., Fasham, M. J. R., Goulden, M. L., Heimann, M., Jaramillo, V. J., et al. (2001). The carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide, Chapter 3. In Climate change 2001: The scientific basis (pp. 185–237). Geneva, Switzerland:IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

Schlesinger, W. H., & Andrews, J. A. (2000). Soil respiration and the global carbon cycle. Biogeochemistry, 48(1), 7–20. doi:10.1023/A:1006247623877.

Sarmiento, J. L., Hughes, T. M. C., Stouffer, R. J., & Manabe, S. (1998). Simulated response of the ocean carbon cycle to anthropogenic climate warming. Nature, 393(6682), 245–249. doi:10.1038/30455.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Kyungpook National University Bokhyeon Research Fund, 2015. We thank NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, United States) for providing OCO-2 satellite data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, Y., Um, JS. Comparative evaluation of XCO2 concentration among climate types within India region using OCO-2 signatures. Spat. Inf. Res. 24, 679–688 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-016-0063-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-016-0063-5