Abstract

By relying on the case of São Paulo, this article seeks to develop a critical look at urban farming and its potential for contributing to food justice. While this activity constitutes a means of subsistence for urban communities, it is also underlain by principles relating to land ownership, which tend to divert attention from its primary role in food systems. There is an important need first to fight against land inequalities and bad housing in São Paulo, before considering urban farming as a lever for food justice. For this study, I made use of qualitative surveys carried out between 2018 and 2022 in São Paulo, during which I conducted 118 interviews with farmers, consumers, shopkeepers, associations and politico-administrative institutions. My results show at first a socio-economic dichotomy between well-off city dwellers who use community gardens and farmers who practise urban farming on the margins of the city. I maintain that the issue of food justice affects the latter and is filtered through a policy of institutional action and visibility. In conclusion, I argue that urban farming is a potential lever for food justice which is still highly constrained by inequalities and land speculation in São Paulo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“He [Zeco] comes from Bahia, like me. But he doesn’t want to be a farmer, he wants to be a Paulistano” (extract from an interview conducted in January 2021). This is how Terezinha, a farmer born in the State of Bahia in the Northeast Region, explains why she is disappointed that her employee, who has worked for her for 16 years, has just accepted a job as a waiter in a restaurant and that he will stop working on her urban farm in São Mateus, in the East ZoneFootnote 1 of São Paulo. When Zeco arrived in the metropolis of São Paulo 1 year ago, he never thought that he would be working again in the roçaFootnote 2, which he left behind when he left his native region. Like many migrants from the Northeast Region, Zeco and Terezinha learned to plant in their childhood and have been taking up this activity again in their new living space: the urban margins.

Urban margins refer to poor areas which are a mix of illegal settlements and consolidated residential areas situated on the outskirts of a dense urban area (Théry, 2017). In a metropolis like São Paulo, they are the result of urban sprawl which accelerated during the second half of the twentieth century, mainly due to an influx of economic migrants from Brazil’s interiorFootnote 3 (Goirand, 2012). In areas which could still be considered rural or peri-urban up until the 1970s–1980s, the urban sprawl, which is less dense in some areas, gives communities access to vacant and arable spaces. Urban farming is an activity used to ensure the food sovereignty of local communities by producing food which is culturally and nutritionally adapted to their needs (Paddeu, 2012). In fact, urban farming which feeds around 700 million citizens, i.e. one quarter of city dwellers worldwide, plays a major role in subsistence (Fumey, 2011).

However, we observe that, in emerging metropolises like São Paulo, the status of urban farming goes beyond its sole productive function and takes on a socio-landscape role useful to the metropolis (Proust, 2020). Indeed, another form of urban farming has been developing for about 10 years in the central and peri-central suburbs of São Paulo, in the form of community gardens, testifying to the emergence of a middle class (Giacchè, 2015). Unlike urban farms on the margins of the metropolis which, as a result of their geographic location, are stigmatised, community gardens coincide with the image of the sustainable city, in line with globalised urban marketing applied to city centres (Rivière d’Arc, 2009). The metropolis gives well-off communities an opportunity to maintain a quality urban environment by making their living space green again, while the aspect of nourishment is secondary.

These differences in function raise issues insofar as urban farming is perceived as a way to develop principles of food justice, which is understood as “the equitable distribution in the way food resources are produced and shared out in a given territory” (Hochedez, 2018, p. 2). As shown by several studies in the scientific literature, the equitable distribution of food resources depends on the improved image of the work of food producers (Hochedez & Le Gall, 2016) and on the significance attached to food sovereignty on the local scale (Slocum et al., 2016). To this end, food justice requires a radical transformation of the neoliberal system and institutional racism of food systems (Sbicca, 2018), particularly in Brazil where racism is an integral part of social structures. For Jessé Souza, racism is the first factor responsible for inequalities in the country and has a direct impact on access to land and food (Souza, 2021).

Similarly, many studies in the scientific literature show that land access has a direct impact on food systems and that food justice cannot prevail unless land can be accessed, particularly in urban areas (Perrin & Nougarèdes, 2020) and in the vicinity of towns (Baysse-Lainé, 2018). The relationship between land and food systems raises strategic issues in urban areas where land encompasses residential, economic, financial and political roles. This article will focus on the issue of land justice in the urban space, as a prerequisite for food justice. In this context, the racialised minorities who practise urban farming on the margins of the city need greater visibility in order to overcome the institutional and spatial invisibility which has been largely responsible for situations of food injustice (Reynolds & Cohen, 2016).

While pursuing a theoretical discussion of food justice, this article will explore this concept in the context of an emerging metropolis. It will seek first to distinguish the several forms of urban farming found in São Paulo, by relying on socio-economic criteria and the profile of relevant actors. It will then show how the visibility and invisibility of urban farming, in a fluid yet constrained urban context, influence its development. Finally, we will emphasise the weight of land speculation-related problems and their repercussions on food justice, by using the example of the East Zone of São Paulo.

Methodology

This article is the fruit of the first results of doctoral research work (Proust (underway),) on urban farming and access to food in the urban margins of São Paulo. It relies, on the one hand, on the theoretical literature in the field of food justice and, on the other, on field research conducted between 2018 and 2022 in São Paulo, where I adopted a qualitative methodology based on interviews and participant observation.

To date, I have conducted 47 interviews with farmers who cultivate land on the margins of São Paulo and 6 with members of community gardens located in well-off central and peri-central suburbs. The interviews consist of four sections: the life trajectory of interviewees (social status, family, migration trajectories), the reasons for which they farm (economic, food, health), the products they cultivate and what they are intended for (home consumption, sale, barter). Most of the time, these interviews were made possible through prior contacts made by people involved in the monitoring of farming activities, i.e. politico-administrative institutions linked to farming, associations, agronomists, shopkeepers and private companies. Forty-two interviews were conducted with this type of actor. In parallel, 23 interviews were conducted with consumers who are part of urban farming distribution networks.

My field research also required me to rely on participant observation, a survey technique offering researchers the possibility of integrating groups of actors whose work cannot be interrupted, often because they do not have enough time to spare. Participant observation consists of researchers joining groups of actors with a view to taking part in various physical tasks, to justify their participation and acceptance within the group (Riou, 2019). In my case, this took the form of farm work, including ploughing a field and running a farm stall at the local market. While, in certain farms, my physical contribution was a compulsory condition of my engagement with farmers, in others this practice was not fully understood nor accepted. This is where my status as a white researcher showed its limitations for an observing participant, in that some farmers seemed to consider their work too degrading or tiring for me. On the whole, however, my immersion allowed me to collect information that may never have been spoken of during interviews, such as particular conflicts between actors and experiences of different forms of violence.

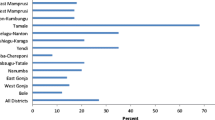

Urban gardens and subsistence farms: two complementary forms of agriculture

Nahmias and Le Caro define urban farming as “a farming activity potentially practised by city dwellers in spaces around the urban area, whether this practice is productive, recreational or otherwise” (Nahmias & Le Caro, 2012). This definition first points to the characteristics of farmers who, in this case, are city dwellers, before touching upon spatial functions and functional tasks linked to agricultural spaces. We understand here that the subject of urban farming is so vast that it is difficult to define it spatially. With this in mind, I propose to distinguish between different forms of urban farming based on the socio-economic profile of actors, rather than rely on the functions of these forms. It seems obvious that actors’ profiles will determine whether the activity is purely for subsistence or is more commercial and that the most vulnerable communities will show greater economic interest in urban farming. In fact, while we tend to distinguish between gardeners who practise farming as a leisure activity in industrialised countries, and professional farmers who practise commercial or subsistence farming in developing countries, situations found in emerging metropolises like São Paulo tend to show the porosity of these categories and question their separation, as these two models are present often in the same space (Mundler et al., 2014). Because my research concerns both community gardens in well-off suburbs and subsistence farms on the margins, I have had the opportunity to compare the socio-economic profiles via the socio-professional category of several actors. The results are shown in Fig. 1. The difference between the two groups of actors resides in the fact that the three residents who practise amenity gardening have another remunerated main activity, while the six farmers who practise subsistence farming, their main activity, do not. Subsistence farmers are often retired or unemployed, farming being their main source of income, the reason why I call them “farmers” as opposed to urban “gardeners” who do not practise this activity for profit. Finally, I choose also to represent two commercial farmers, despite the fact that they are under-represented in my research and constitute a minority of urban farmers.

The first model identified is a form of agriculture practised by well-off and, most often, white citizens within recreational and amenity community gardens (hortas comunitárias). There are 105 community gardens across the metropolis of São PauloFootnote 4, distributed relatively evenly with, nonetheless, a concentration in the centre-west of the urban stain. They began to multiply during the 2010s in the well-off suburbs of São Paulo, i.e. in the peri-central ring and centre-west (Visoni & Nagib, 2019). These gardens benefit from wide publicity and significant media coverage. For this reason, they represent the “visible” agriculture of the public authorities, which aim to produce speeches and ideas to further the social struggles, rather than to produce food (Caldas & Jayo, 2019). For those who take part in these gardens, the idea is to reappropriate the “right to the city” through the medium of peaceful activism, with a view to transforming the land appropriation mode in the urban space (Nagib, 2020). The “right to the city” is understood as a direct action, carried out in the urban space, for social justice, solidarity and respect for nature, as opposed to the principles of financial capital reproduction. Urban farming constitutes new democratic perspectives for the production and use of the urban space (ibid.).

These community gardens are part of a food movement supported mainly by white, educated and well-off upper classes (Paddeu, 2012). According to testimonies gathered on site, individuals seek to change the structure of the food system in favour of communities who have no voice or the power to change the situation. It turns out that these gardens do not offer real prospects for food and are often limited to recreational farming which city dwellers use to embellish their meals. Harvests which are shared between garden members, who are already aware of the dangers of industrial food, seldom make it to the plates of communities in precarious food situations.

This is a challenge agri-food initiatives face when they have difficulty in penetrating working-class suburbs. In France, associations for the maintenance of peasant farming (AMAP) also reveal their inefficiency in reaching a heterogenous public, by maintaining same-circle dynamics and member homogeneity, where members are part of a highly educated, upper middle class (Lalliot, 2021). The same has been noted in the USA, where the link between class inequalities and racial issues is translated into alternative food movements led by a white value system. Racial minorities do not identify with or participate in these movements (Guthman, 2008). Yet one should not deny the potential of community gardens, which could play a major role in food justice, by reducing socio-environmental inequalities in poor suburbs where the community is disadvantaged (Duchemin et al., 2008). Based on this model, purchasing initiatives like that of the VRAC association, in France, aim to reduce inequalities in accessing organic produce, by working directly with working-class suburbs through bulk-buying organisations and solidarity membership (Tavernier, 2019). In São Paulo, the Viveiro Escola União also supports this type of initiative, by mobilising people in precarious situations. Situated in the East Zone of the city, in the district of São Miguel Paulista, this centre accommodates a co-operative of women originating from Bahia, many of whom were victims of domestic violence. In 2002, they launched the project “Quebrada Sustentável”Footnote 5 which focuses on growing healthy food and selling it to residents at affordable prices. While this relatively recent co-operative was born first from a need for food, today it assumes other functions, such as enabling residents to widen their circle of acquaintances, enabling racially marginalised women to assert their solidarity and promoting the role of the environment and the landscape in the greening of the suburbs. As such, community gardens are always multifunctional spaces, whether they are cultivated by residents in precarious situations or well-off city dwellers, the only difference being that food production remains the key objective of the gardens situated on the margins of the city (Fig. 2).

Beyond the socio-economic profile of farmers, the issue of race constitutes another form of differentiation between gardeners from the centre of town and farmers from the margins. Indeed, while gardeners are most often the descendants of Europeans—Italians, Spaniards and Germans—who arrived in Brazil during the nineteenth century and settled in São Paulo a long time ago, farmers are mainly black or mixed-race people who come from the rural areas of Brazil. This is not surprising considering that the margins of the city are populated mainly by residents who define themselves as poor, black and working class (Tiarajú d’Andrea, 2013). Urban farming actors are, therefore, only a reflection of the space in which they live. In fact, I have found an overrepresentation of migrants from the North-East Region, particularly from Bahia and Pernambouc, in the gardens on the margins in the East Zone of São Paulo where I conducted most of my surveys.

For these communities, urban farming reflects culture and memory. This dimension is also found in Toronto (Canada) where migrant gardeners bring local knowledge from their place of origin, which they adapt to urban gardening spaces which, then, reflect migrants’ memory through cultural landscapes (Baker, 2004). In this we find the link between the cultural dimension of urban farming and food justice, insofar as urban farming is a lever for a transition towards “ecologically sound, economically viable and socially fair food systems” (ibid., p. 308). This has also been observed in Malmö (Sweden), where plots worked by Asian residents make it possible to preserve traditional food varieties and cultural dietary practices in a migration situation, thereby meeting the specific needs of communities who grow ethnic products (Hochedez, 2018). The transmission and exchange of knowledge constitute vernacular foodscapes, which appear as the result of an appropriation of the site by migrant communities, the gardens then making it possible to map out individual and collective self-topographies, i.e. “to recount one’s own story through the shaping of the place” (Mares & Peña, 2011, p. 208).

In São Paulo, urban gardens appear as geo-symbols with a symbolic dimension that could be almost sacred, in that they enable migrants to reconnect with ancient and culturally important food cultures which have partially disappeared with the advent of industrial food. This is the case, for example, with endemic plants which today, in Brazil, are called “Plantas alimentícias não Convencionais”Footnote 6 (Panc) often thought incorrectly to be self-propagating, because they contain significant nutritional or even medicinal qualities (De Albuquerque, 2018). For example, the elephant ear (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), a plant with large leaves, rich in fibres and antioxidants, can be consumed in soup or juice. Among these plants, we also find the nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) which has an edible flower. We noted that city dwellers in São Paulo are showing growing interest in these plants and are turning to urban farmers to obtain them. The latter, for whom these plants have always been part of their diet, do not see their commercial potential. Jorge, who is an urban farmer in the North Zone of São Paulo, has many “Panc” in his garden, but does not market them: “This grows naturally, there is nothing to be done about it, one can’t cultivate it. It’s a wild plant, it belongs to the earth” (extract from an interview conducted in February 2020). City dwellers’ growing interest in these plants represents a potential opportunity for farmers but could also constitute a risk, insofar as these products are being decommodified and could become inaccessible to the communities who are used to consuming them, following the example of quinoa production in the highlands of Bolivia (Kerssen, 2015).

These plants represent a means to expanding food availability on the margins, with healthy and culturally adapted food. They also favour the exchange and transmission of knowledge between communities coming from very different socio-economic environments, in a country where social boundaries are often impassable. In the rest of this article, I will show how making urban farming visible constitutes a major issue in establishing fairer food structures.

Visibility and invisibility: urban farming experience to reduce inequalities

In São Paulo, the visibility of urban farming has been widely reinforced since 2016, with the launch of the “Ligue os Pontos” programme by the City of São Paulo. This programme, which is financed by Bloomberg Philanthropies, aims at taking a census of farmers in the City of São Paulo to create maps, with a view to establishing protocols for transitioning to organic farming. The results of the programme, which are available on the platform Sampa+RuralFootnote 7, report 728 farming units throughout town, of which 70% are identified as family farms. While urban farming has been stigmatised and made invisible in the urban space of São Paulo, it seems to have benefitted from renewed interest from public authorities and the media over the past few years. This trend has been observed worldwide, in different contexts, where the potential of urban farming for supplying cities with fresh food has been put forward (McClintock et al., 2012). In this context, the improvement of the image of urban farming has encouraged food systems to offer quality food to consumers with a view to reducing malnutrition-related diseases (Smith, 2007). The COVID-19 pandemic has also played a role in this regard, by reinforcing the importance of community gardens and urban farms, which have experienced an increase in participants during the health crisis, to compensate for food insecurity and the precarious situations of certain communities (Girotti Sperandio et al., 2022).

The role of the media is particularly strategic in this movement, as shown by the wide coverage of urban farming in the São Paulo broadcasts of the television channels, Globo RepórterFootnote 8 and Globo RuralFootnote 9. Urban farming is shown as a means of supplying fresh and healthy food to disadvantaged communities, in what the journalists present as a “food desert”, i.e. a deficient urban space where communities cannot obtain healthy food at affordable prices (Paddeu, 2012). Yet, this term, which is often used by the media to refer to urban margins, seems debatable. The term “desert” implies a shortage, or even an absence, when in fact the food system of São Paulo is fairly well developed up to the margins of the city, and is central to the commercial and financial dynamics of Latin America and the rest of the world (Chatel & Moriconi-Ebrard, 2018). A testimony to this is the “Companhia de Entrepostos e Armazens Gerais de São Paulo”Footnote 10 (Ceagesp), which is the largest wholesale market on the Latin American continent, representing, on its own, 35% of the total quantity of products marketed in all the central warehouses of the country (Wegner & Belik, 2012), with an average of 283,000 tons of products sold every monthFootnote 11. The Ceagesp also supplies street markets and retail department stores. The latter, which have become increasingly competitive in the sale of fresh produce, have in fact—for several decades already—instigated the restructuring of fruit and vegetable markets worldwide and in Latin America in particular (Reardon & Peter Timmer, 2007).

The presence of this relatively stable food system does not point to the existence of “food deserts” in São Paulo. Yet, we find that socio-economics and race are determining factors in the accessibility of quality products, where white communities have better access to the same products than other communities (Holt Giménez, 2014). This is the case particularly in a country where 350 years of slavery, still in existence in certain regions, have left indelible marks on the distribution of wealth between socio-racial classes. As Cedric J. Robinson asserts in Black Marxism, the tenet of racial capitalism maintains that the capitalist model is intrinsically linked to racial inequalities and that, therefore, food systems depend on racial and class inequalities to work (Robinson, 2000). In practice, this is shown in the consumption of high calorie food of low nutritive value consumed mainly by racial minorities, who are more likely to live in marginalised suburbs and be targeted by the advertising strategies of the food-processing industry (Ramírez, 2015; Jones, 2019).

That being the case, how can we describe this imbalance between food supply in well-off and working-class suburbs? This is seen in supermarkets and on the streets, where industrialised products and fast foods are overrepresented compared to fresh produce. The term “food apartheid” seems to be more appropriate in describing this reality, in that it highlights the social and racial components, while also pointing out spatial inequalities (Brones, 2018). My main hypothesis relies on the idea that, even if the portion of urban farming supplying the metropolis seems small, it is still meaningful for people insofar as it gives rise to social organisation and political mobilisation. In this light, urban farming practised by racial minorities on the margins of the city appears to be an efficient way to thwart the dominant system. According to the principles of food justice, this leads to the reappropriation of agricultural production, on the one hand, and to the consumption of better-quality food, on the other. Urban farming, therefore, constitutes a form of resistance to capital accumulation, spatial racialisation and land accumulation (Mcclintock, 2018).

Beyond economic benefits, food justice also posits a parallel with the physical and mental health of communities, encouraged by urban farming. I was able to identify health issues which encourage people to practise urban farming similar to those in the disadvantaged suburbs of the Bronx in New York (Paddeu, 2012). Many testimonies of farmers in São Paulo mention the desire to practise an outside physical activity, which could also help them psychologically, especially when farmers are retired. This is the case for Ivan, a farmer in the East Zone of São Paulo who worked in a factory his whole life and who now farms as a pastime: “I worked for 22 years in a factory for domestic electrical appliances, 15 years in the petrochemical industry and now I am retired. I must remain active!” (extract from an interview conducted in April 2022). This issue seems crucial for migrants from the Northeast Region, like Helena, a native of Pernambouc and farmer in the East Zone of São Paulo: “When I was eight years old, I was already working in the fields [roça], I just can’t sit and do nothing” (extract from an interview conducted in April 2021).

Beyond their personal health, farmers enjoy producing and selling healthy food which, for the most part, is grown free of chemicals. Chemical input is of particular concern for women farmers like Ana, who has been practising agroforestry in the South Zone of São Paulo for the past 30 years and who claims to be “selling health to people” (interview conducted in April 2021). It is a form of ecofeminism which, before becoming theorised in the countries of the Norths (d’Eaubonne, 1974), was first a set of movements and practices originating from the countries of the Souths, which offer a common reading of feminist, ecological and anticolonial struggles by questioning anthropocentrism in environmental issues (Bahaffou and (underway),). Underlying any initiative of urban subsistence, farming is the desire to access good quality food, grown ecologically, without having to pay the exorbitant prices charged by organic food chains. This is the case of Terezinha, already introduced at the beginning of this article, who began to grow food because of health problems and who, today, makes a personal commitment to members of her suburb (Fig. 3). Concerning the market organised at her farm, she declares: “I’m not doing this for myself only […] but I reach at least a dozen people [a day] and that’s what gives me strength” (extract from an interview conducted in January 2021). Generally, urban farming is organised first around self-sufficiency which, when farmers manage to structure their production, then motivates the development of commercial strategies.

Implementing organic food chains on the margins of the city is a major issue for a metropolis like São Paulo. By offering farmers a means to work positively on their own and their community’s health from a nutritional, physical and mental point of view, urban farming contributes to improving the image of farm work, which seems to be central to food justice (Leloup, 2016). It also contributes to changing the precarious nature of classic farming environments, in particular for women who are most often pluriactive farmers, wives of farmers or without specific status, particularly in Brazil (Chiffoleau, 2012). Women farmers, who are made invisible and undermined by productivist farming systems, often become farm managers in urban agricultural units, which offer better opportunities for women’s empowerment (Trauger, 2007). In São Paulo, there is a conceptual and activist parallel between feminism and agroecology, as can be seen from the “Rede de Agricultoras Paulistanas Periféricas Agroecológicas”Footnote 12 (RAPPA) created in 2020Footnote 13.

If women seem to be more independent and autonomous in urban farming than in certain rural environments, it is also because today’s urban farming has merged with an activist practice informed by liberal socio-cultural codes, especially through community gardens in the central suburbs. These initiatives are part of an action plan offering a different vision of farm work, one in which racial and gender oppression are opposed. This conceptual renewal affects the general perception of agriculture, including on the margins of the city, and gives weight to a more equitable and balanced model. In this sense, the reasoning underlying urban farming is closely akin to the idea of daily mobilisation for subsistence, in which women are invited to play a pivotal role (Pruvost, 2021). From this, we can conclude that the urban farming model of shared gardens is compatible with the subsistence model on the margins, where both influence one another to reinforce their political power and spatial coverage.

At this stage, I propose to question the place given to subsistence farming in the land dynamics of the city. The hypothesis is that urban farming is a land use method constrained by its proximity to the city, which influences its development and sometimes hampers its objective of becoming a lever for food justice.

Land justice in the east zone: an issue for urban farming

In Brazil, the land issue has always been central to the claims of family farmers. The Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) has been fighting, since 1985, for land reform and access for small farmers and to ensure that their communities become more involved in the political life of the country (Starr et al., 2011). This fight is also taking place in urban areas where farmers are not always included in rural development plans. São Paulo had to wait until 2014 for the modification of the “Plano Diretor Estratégico” (PDE), the town planning document which dictates the city’s land policy, before agricultural rural areas located on the municipal boundaries of São Paulo were included. Through this process, one-third of the surface area of the city was rezoned as part of the rural area (PDE, 2014). This policy, orchestrated by then mayor Fernando Haddad (PT), made it possible to increase the number of beneficiaries of the “Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar”Footnote 14 (Pronaf) and, therefore, to widen farmers’ institutional supervision.

Out of the 728 farming units identified on the municipal perimeter by the Ligue os PontosFootnote 15 programme, 119 are located in the East Zone of the city, mainly on public or private land containing high voltage overhead power lines supplying São Paulo. The Enel Distribuição São Paulo Company, the largest owner of power lines in the metropolis, manages an important portion of these concessions. Since the 1980s, this company has been part of a family farming support programme which authorises farmers to cultivate under the power lines, with a view to occupying these spaces and avoiding “invasions”Footnote 16. In exchange, farmers undertake not to reside on this land nor build permanent structures—an instruction which is not always observed. At the beginning of the project, 248,000 individual gardens and 4700 community and school gardens were created across the entire metropolis (Caldas & Jayo, 2019). Subsequently, this initiative received little political monitoring and the situation deteriorated greatly, leaving farmers without valid property use agreements and in precarious situations (Giacchè & Porto, 2015).

In 2015, the Enel Distribuição São Paulo Company launched the Hortas em Rede programme (which means “networked vegetable garden”), in conjunction with the non-governmental organisation Cidade Sem Fome (CSF) which builds urban gardens in the East Zone. Hortas em Rede has a surface area of 1 hectare and has 26 farm workers who receive a fixed salary from the company. This project creates jobs in a marginalised suburb, in the same way as independent farmers who work for themselves under the power lines, showing how similar communities can adapt differently to the opportunities offered by these spaces. However, we have noticed that the independent farmers have been stigmatised and that their methods of cultivation are deemed “informal” by the company that perceives them as outsiders. Around 40 of these independent farmers created the East Zone Farmers’ Association (AAZL) in 2002, with a view to gaining political influence in order to be heard and more visible. The rest of the farmers, mentioned in Fig. 4 as being “non-affiliated” farmers, are those who did not wish to join the AAZL, often because their land tenure is unclear because they do not have a valid, if any, property use agreement and they prefer to remain discreet to prevent eviction.

The issue of the legitimisation and media visibility of the farmers operating under the power lines shows certain limitations, particularly when the material and land conditions are not guaranteed. Interviews show that these farmers have no desire to expand their consumer network or assert their presence politically: they simply want to grow food for home consumption. The prospect of greater visibility is inconvenient and may even represent a danger; they feel threatened by evictions and prefer to remain out of the sight of territorial authorities and the electricity company, in particular. From this perspective, incorporating farmers into an economic and political system may reinforce their vulnerability, exposing activities that were ignored until now, in contested spaces (Adam & Mestdagh, 2019). The discreet character of farming activities in town constitutes a voluntary choice by farmers provoked by their urban context.

By allowing farmers to cultivate the land under power lines, the electricity company uses farming as a land use method to control urban sprawl. Farming thus fulfils a “public service”, becoming compatible with protecting strategic territories (Scheromm et al., 2014). Through this mechanism, we have a situation in which a group of marginalised actors, i.e. farmers, is used to control the spatial protest of other oppressed groups that do not have access to housing. This situation, which is advantageous for the electricity company, fails to take care of independent and non-affiliated farmers who suffer from institutional invisibility. Indeed, it often happens that property-use agreements issued by the company are not updated, which exposes farmers to the risk of eviction, as explained by Terezinha: “It was an old agreement, I did not even know who the owner was. Because one gives the agreement to another who in turn gives it to another, you see? And it’s a friend who gave it to me […]. He just gave it to me and we had to run after that document. We’ve only just obtained it, and now I have an agreement. But I didn’t have one for 10 years”. (extract from an interview conducted in May 2022).

Moreover, many farming activities taking place under the power lines are kept hidden by the farmers because they are forbidden by the company, encouraging further spatial invisibility of urban farming. For example, farmers are not permitted to breed animals on their plots. Yet, in Fig. 5, we can see henhouses on the farm of João (not the farmer’s real name), in the middle ground on the left. These henhouses are protected by several dogs to prevent theft. The same applies to the banana trees, which can be seen in the middle ground on the right. Farmers are not permitted to plant high trees because these run the risk of touching the electric lines and creating short circuits in the network. When I asked João how he managed to have these banana trees and henhouses on his plot, despite the frequent controls by the company’s inspectors, he declared, “The inspector? All one has to do is be friendly with him!” I then asked him if he ever had to resort to bribes, his reply was “No, just bananas, lettuces from time to time” (extract from an interview conducted in July 2022). Therefore, the lack of visibility of urban farming is characterised, firstly, by ambiguous land situations and, secondly, by the camouflage of certain activities that are often more profitable for the farmers.

Beyond agriculture, other far more illicit activities are also present on these plots, which also explains why the company is relatively tolerant of the farmers. These activities are run by criminal organisations, such as the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), which controls many dealings and organises illegal plot “invasions” in the metropolis. Indeed, we find that any issue concerning the land on the margins of São Paulo has to be tackled by taking into account organised crime and illegality (Simoni Santos, 2015), where the PCC plays the role of “peacemaker”, substituting itself for the police, with kangaroo courts and infiltrating the social fabric to establish powerful authority (Martins de Carvalho, 2021). Because of these criminal activities, Enel Distribuição São Paulo often adopts a policy of “laisser-faire”, and leaves it to farmers to get along with the criminals. As a result, farmers find themselves in an ambiguous relationship with those who invade the land, as explained by Terezinha: “The majority of plots, in fact they are invasions, people invaded them, and them [Enel Distribuição], they want us to deal with the plots and remove people from there. Except that it’s not for us to do this, that’s their job!”. In this situation, farmers are expected to negotiate their space with people who want to live there, often because there is a lack of housing. Urban agriculture then appears as a limiting element of the urban landscape.

Land resources taken over by criminal organisations are also the result of the State’s indirect encouragement of spontaneous and irregular urbanisation through not offering efficient solutions to poor housing. This also involves a financial mechanism, insofar as urbanised areas may then fall under the urban tax system, the Imposto predial territorial urbano (IPTU), which is much higher than the rural tax system, the Imposto territorial rural (ITR). This makes it indirectly possible for illegal occupations and invasions to flourish, particularly around rural properties located near recently urbanised areas, as explained by Ana who practises agroforestry in the South Zone of São Paulo: “We see people around deforesting to build, but the government does nothing […]. With this urbanisation, we run many risks, the risk of being mugged, of people bursting into our property. We have a colleague who has already been held hostage [...]. When it was properly rural here, we didn’t have these difficulties […]” (extract from an interview conducted in March 2021). In addition to the tax system, there is the issue of the variability of land prices which fluctuate drastically in the urban context. The farmers on the margins of São Paulo, who are rarely the owners of their plots, are affected by land speculation and properties “kept in reserve” by the financial sector. In this case, properties are let to producers until it becomes more profitable to use them for services and commercial activities (Alessandri Carlos, 2008). Land speculation may also favour rural land owners who keep their own properties in reserve until they become development areas and can be sold per square metre. Farmers are proactive in this regard, taking advantage of these metropolitan land speculation mechanisms (Faliès, 2013).

We see that urban farming is, above all, an activity which is part of a space governed by socio-spatial asymmetries and financial mechanisms. For this reason, urban farming does not always make it possible to fight against inequalities and may even contribute to reinforcing them. For example, it has been shown that urban farming can favour gentrification when vacant plots are transformed into community gardens increasing the land value (Allen, 2010). Similarly, urban farming, which relies on mutual aid and solidarity to feed people, may sometimes play the neoliberalism card, by adopting a social approach that thwarts the role of the State, and justifies the weakness of its intervention on the margins (McClintock, 2014). While these approaches are, of course, different, they also show that urban farming does not constitute a food justice practice in and of itself but that it depends, above all, on its spatial context to achieve this. We must also consider that “political urban farming”, the process through which power relations at play in the city influence urban farming, is understood as a territorial resource to meet the demands of the metropolitan urban context (Engelbert, 1968).

Conclusion

Whether urban farming in São Paulo concerns subsistence, commercial or leisure activity, it contributes to the food justice of communities by democratising access to land and self-production. This is the case for internal migrants in particular who, through the cultivation of endemic plants, bring vernacular foodscapes to the urban environment. However, the objective of the community and the self-organised functioning of these spaces, even without the benefit of sufficient political and economic support, is not actually to supply the metropolis with food. It is more about a timely and specific food support system on the local scale to enable marginalised communities to access, at affordable prices, healthy and appropriate food, meeting the objectives of food sovereignty (Thivet, 2012). Moreover, the productive and subsistence role of urban farming is underlain by politico-financial principles, which are part of the mechanisms of an emerging metropolis, particularly on the margins where land speculation and inequalities are most blatant. Farmers are encouraged to settle in strategic urban areas, with a view to creating a protective barrier against urban sprawl, but are not allocated the resources needed to develop this objective. These mechanisms of urban agricultural exploitation highlight the fact that farming activities are not part of the contemporary conception of the urban model, agricultural production being seen as belonging to rural soil (Tornaghi, 2016). Against the bio-regional conception of the metropolis, the city relies on agriculture to ensure the reproduction of its financial capital and to control land dynamics, rather than to guarantee food.

As city dwellers, urban farmers are included in the thought system of the city and become actors involved in the political dynamics underlying it. In this light, the city becomes a space for debate, a political arena where positions are taken and farmers are taken to task. This politicisation is encouraged by the fact that food is always a political issue that reflects relations of domination (De Castro, 1951). It is, therefore, impossible to think about urban farming without adopting a critical stance on space and taking into account the politico-symbolic issues of food, especially in a society like Brazil, where food supply is orchestrated by a “hunger policy” which limits the possibilities of liberation from relations of domination (Dion, 1953). Yet, we observe an obvious—and necessary—porosity between the city and the country, which calls for the establishment of solid political structures to improve the status of farmers in urban areas. In fact, while most farmers request more financial and institutional support, others seek rather to confront the authorities to oppose any standardisation and appropriation of their activities. Through self-organisation, the centering of the community and the formation of grassroots governance structures, farmers claim a political autonomy that stands against politico-financial structures and the State (Warshawsky, 2014). In this, the anti-establishment character of urban farming echoes the fact that the principles of control are being questioned and that power relations are being deeply disrupted, forcing a reconsideration of food and the political system as a whole.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The city of São Paulo is divided into five large zones: the East, West, North, South and Central Zones.

“roça” is a term associated with the Northeast culture which refers to the family farming unit that grows food for home consumption, as opposed to “fazenda” which refers to export farming (Martins De Carvalho, 2021).

This term refers to rural areas in Brazil, as opposed to coastal regions, which are often more urbanised and developed.

Community gardens of São Paulo [consulted on 03/11/2022] : https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1Jv4a5V6_DJq7c9OJSCLyF182LzU&ll=-23.553617500791425%2C-46.843562497445184&z=10

“Sustainable Margins” (our translation). The term quebrada, which literally means “broken”, is used to refer to the working-class suburbs on the margins of the city.

“Unconventional food plants” (our translation)

Plateforme Sampa+rural de la mairie de São Paulo [consulted on 29/09/2022]: https://sampamaisrural.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/categoria/agricultores

Saúde a mesa [12/02/2021] 38:00: https://globoplay.globo.com/v/9265660/

Lavouras urbanas levam alimento e trabalho para moradores da periferia de São Paulo [28/11/2021] 13:46: https://g1.globo.com/economia/agronegocios/globo-rural/noticia/2021/11/28/lavouras-urbanas-levam-alimento-e-trabalho-para-moradores-da-periferia-de-sao-paulo.ghtml

“Company of Warehouses and General Stores of São Paulo” (our translation)

CEAGESP Website [consulted on 20/02/2022]: https://ceagesp.gov.br/entrepostos/etsp/

Network of Agroecological and Peripheral Female Urban Farmers (our translation)

The objective of the RAPPA is to reinforce the economic autonomy and participation of women in the construction of agricultural policies on the basis of agroecology [consulted on 03/11/2020]: https://agroecologiaemrede.org.br/organizacao/rede-de-agricultoras-perifericas-paulistanas-agroecologicas-2/

National Programme for Strengthening Family Farming (our translation) which offers technical assistance as well as subsidies and gives access to procurement contracts such as the National School Feeding Programme (PNAE) and the Food Acquisition Programme (PAA).

Website of Ligue os Pontos [consulted on 01/10/2022]: https://ligueospontos.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/

This is the name given to the process of informal urban sprawling in Brazil, whether it concerns the extension of existing favelas or the construction of new ones.

References

Adam, M., Mestdagh, L. (2019). Invisibiliser pour dominer. L’effacement des classes populaires dans l’urbanisme contemporain. Territoire en Mouvement, 43. https://doi.org/10.4000/tem.5241

De Alburquerque, L. (2018). Les initiatives citoyennes à São Paulo vers une alimentation en lien avec l’adaptation aux changements du climat : la place des ‘plantes alimentaires non conventionnelles – PANC’s’. Urbanités, 10. https://www.revue-urbanites.fr/10-de-alburquerque/. Accessed Aug 2022.

Alessandri Carlos, A. F. (2008). Dynamique urbaine et métropolisation, le cas de São Paulo. Confins, 2. https://doi.org/10.4000/confins.1502

Allen, P. (2010). Realizing justice in local food systems. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq015

Bahaffou, M. (underway). Un écoféminisme autochtone : représentations, discours et cosmologies animalistes. PhD thesis in Philosophy in preparation at the University of Amiens in cotutelle with the University of Ottawa

Baker, L. E. (2004). Tending cultural landscapes and food citizenship in Toronto’s community gardens. The Geographical Review, 94(3), 305–325. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30034276. Accessed Oct 2022.

Baysse-Lainé, A. (2018). Terres nourricières ? : la gestion de l’accès au foncier agricole en France face aux demandes de relocalisation alimentaire : enquêtes dans l’Amiénois, le Lyonnais et le sud-est de l’Aveyron. PhD thesis in Geography at the doctoral school of Social Sciences of Lyon

Brones, A. (2018). Karen Washington: It’s not a food desert, it’s a food apartheid. Guernica/15 years of global arts & politics. https://www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/. Accessed Apr 2021.

Caldas, E., & Jayo, M. (2019). Agricultures urbaines à São Paulo: histoire et typologie. Confins, 39, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.4000/confins.18683

Chatel, C., & Moriconi-Ebrard, F. (2018). Les 32 plus grandes agglomérations du monde: comment l’urbanisation repousse-t-elle ses limites ? Confins, 37, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/confins.15522

Chiffoleau, Y. (2012). Circuits courts alimentaires, dynamiques relationnelles et lutte contre l’exclusion en agriculture. Économie rurale, 332, 88–101. https://doi.org/10.4000/economierurale.3694

D’Eaubonne, F. (1974). Le féminisme ou la mort (p. 336). Université de Californie.

De Castro, J. (1951). La géopolitique de la faim (p. 408). Éditions sociales.

Dion, G. (1953). Compte rendu de [De Castro, Josué, ‘Géopolitique de la faim’, un volume, 331 p.]. Relations Industrielles Industrial Relations, 8(4), 411–413. https://doi.org/10.7202/1022931ar

Duchemin, E., Wegmuller, F., & Legault, A-M. (2008). Urban agriculture: Multi-dimensional tools for social development in poor neighbourhoods. Field Actions Science Reports, 1, 43–52.

Engelbert, E. A. (1968). Agriculture and the political process. In R.J. Hildreth (Ed.), Readings in agricultural policy, (pp. 140–149). University of Nebraska Press

Faliès, C. (2013). Espaces ouverts et métropolisation entre Santiago du Chili et Valparaíso: produire, vivre et aménager les périphéries. Phd thesis in Geography at the University of Paris 1

Fumey, G. (2011). Le défi alimentaire. In Martine Guibert & Yves Jean (Eds.), Dynamiques des espaces ruraux dans le monde, (pp. 101–113). Armand Collin

Giacchè, G. (2015). De la ville qui mange à la ville qui produit : l’exemple des Hortelões Urbanos de São Paulo. Dossier : transition sociale et environnementale des systèmes agricoles et agro-alimentaires au Brésil, ESO Rennes

Giacchè, G., & Porto, L. (2015). Políticas publicas de agricultura urbana e periurbana: uma comparação entre os casos de São Paulo e Campinas. Informações Econômicas, 45, 45–60. http://www.iea.sp.gov.br/ftpiea/publicacoes/ie/2015/tec3-1215.pdf. Accessed Oct 2019.

Girotti Sperandio, A. M., Bonetto, B., Fraga Lima, T., & Conceição Guarnieri, J. (2022). Cidades pequenas e agricultura urbana no contexto da pandemia Covid-19. Revista de arquitetura, cidade e contemporaneidade, 6(20). https://periodicos.ufpel.edu.br/ojs2/index.php/pixo/article/view/20912/0. Accessed Sep 2022.

Goirand, C. (2012). Le Nordeste dans les configurations du sociales du Brésil contemporain. CERISCOPE Pauvreté. http://ceriscope.sciences-po.fr/pauvrete/content/part2/le-nordeste-dans-les-configurations-sociales-du-bresil-contemporain. Accessed July 2022.

Guthman, J. (2008). ‘If only they knew’: Color blindness and universalism in California alternative food institutions. The Professional Geographer, 60(3), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120802013679

Hochedez, C. (2018). Migrer et cultiver la ville : l’agriculture communautaire à Malmö (Suède). Urbanités, 10. https://www.revue-urbanites.fr/10-hochedez-malmo/. Accessed Oct 2022.

Hochedez, C., & Le Gall, J. (2016). Food justice and agriculture. Justice Spatiale | Spatial Justice, 9, 1–31. https://www.jssj.org/article/justice-alimentaire-et-agriculture/. Accessed Jan 2020.

Holt Giménez, E. (2014). Racism and capitalism: Dual challenges for the food movement. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems and Community Development, 5(2), 23–25. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.052.014

Jones, N. (2019). Dying to eat? Black food geographies of slow violence and resilience. ACME, 18(5), 1076–1099. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1683. Accessed July 2020.

Kerssen, T. (2015). Food sovereignty and the quinoa boom: Challenges to sustainable re-peasantisation in the southern Altiplano of Bolivia. Third World Quarterly, 36, 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1002992

Lalliot, M. (2021). Les amapien.ne.s d’Ile-de-France sont-ils des bobos? Le réseau des Amap en Île de France. http://www.amap-idf.org/amapiennes_ile-de-france_sont-ils_bobos_123-actu_413.php. Accessed Mar 2022

Leloup, H. (2016). Proximity agriculture in Lima: Is a fairer production system emerging for producers and consumers? Justice Spatiale/Spatial Justice, 9, 1–25. https://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/JSSJ9_04_ENG.pdf. Accessed Mar 2020.

Mares, T. M., & Peña, D. G. (2011). Environmental and food justice. Toward local, slow, and deep food systems. In H. A. Alkon, & J. Agyeman (Eds.), Cultivating food justice: Race, class and sustainability. (pp. 197-219). The MIT Press. https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/4423/Cultivating-Food-JusticeRace-Class-and. Accessed July 2022.

Martins De Carvalho, L. (2021). Agricultura urbana em contextos de vulnerabilidade social na Zona Leste de São Paulo e em Lisboa. Tese de doutorado, Faculdade de Saúde pública, Universidade de São Paulo.

McClintock, N. (2014). Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: Coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environment, 19(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.752797

McClintock, N. (2018). Urban agriculture, racial capitalism, and resistance in the settler-colonial city. Geography Compass, 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12373

McClintock, N., Wooten, H., & Brown, A. (2012). Towards a food policy ‘first step’ in Oakland, California: A food policy council’s efforts to promote urban agriculture zoning. Journal of Agriculture Food Systems and Community Development, 2(4), 15–42. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2012.024.009

Mundler, P., Consalès, J-N., Melin G., Pouvesle, C., & Vandenbroucke, P. (2014). Tous agriculteurs ? L’agriculture urbaine et ses frontières. Géocarrefour, 89(1-2). https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.9399

Nagib, G. (2020). Agricultura urbana como ativismo na cidade de São Paulo: o caso da Horta das Corujas. Master's Dissertation, Faculty of Philosophy, Literature and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo

Nahmias, P., & Le Caro, Y. (2012). Pour une définition de l’agriculture urbaine : réciprocité fonctionnelle et diversité des formes spatiales. Environnement Urbain / Urban Environment, 6, 1–16. https://journals.openedition.org/eue/437. Accessed July 2022.

Paddeu, F. (2012). L’agriculture urbaine dans les quartiers défavorisés de la métropole New-Yorkaise: la justice alimentaire à l’épreuve de la justice sociale. VertigO, 12(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/vertigo.12686

PDE. (2014). Plano diretor Estratégico do Município de São Paulo. Gestão Urbana de São Paulo. https://gestaourbana.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/arquivos/PDE-Suplemento-DOC/PDE_SUPLEMENTO-DOC.pdf. Accessed Feb 2020.

Perrin, C., & Nougarèdes B. (2020). Le foncier agricole dans une société urbaine. Innovations et enjeux de justice. Cardère éd., 358

Proust, A. (underway). Nourrir São Paulo par ses marges. Dynamiques et enjeux socio-spatiaux de l’agriculture périurbaine à l’échelle métropolitaine. PhD thesis in geography in preparation at the University of Paris 1

Proust, A. (2020). Se nourrir par l’agriculture urbaine à São Paulo. Enjeux socio-spatiaux d’un système alimentaire métropolitain. Echogéo, 54. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.20585

Pruvost, G. (2021). Quotidien politique: Féminisme, écologique, subsistance. La découverte, 400

Ramírez, M. M. (2015). The elusive inclusive: Black food geographies and racialized food spaces. Antipode, 47(3), 748–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12131

Reardon, T., & Peter Timmer, C. (2007). Transformation of markets for agricultural output in developing countries since 1950: How has thinking changed? In Handbook of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 3 (pp. 2807–2855). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0072(06)03055-6

Reynolds, K., & Cohen, N. (2016). Beyond the Kale. Urban agriculture and social justice activism in New York city, University of Georgia Press

Riou, P. (2019). Habiter c’est toujours cohabiter. Humains et animaux d’élevage en ville : penser la cohabitation à Détroit. Master’s Dissertation, University of Paris 1

Rivière d’Arc, H. (2009). São Paulo. Les conditions contradictoires de la ‘durabilité’ dans le centre-ville. In H. Rivière d’Arc & C. Duport (Eds.), Centres de villes durables en Amérique latine : Exorciser les précarités ? (pp. 123–144), Collection Travaux et Mémoires, Éditions de l’IHEAL

Robinson, C. J. (2000). Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition, The University of North Carolina Press

Sbicca, J. (2018). Food justice now! (p. 280). University of Minnesota Press

Scheromm, P., Perrin, C., & Soulard, C. (2014). Cultiver en ville… Cultiver la ville? L’agriculture urbaine à Montpellier. Espaces et Sociétés, 3(158), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.158.0049

Simoni Santos, C. (2015). Espaços penhorados e gestão militarizada da fronteira urbana. In C. Simoni Santos (Ed.), A fronteira urbana: urbanização, industrialização e mercado imobiliário no Brasil. Annablume

Slocum, R., Cadieux, K. V., & Blumberg R. (2016). Solidarity, space and race: Toward geographies of agrifood justice. Justice Spatiale | Spatial Justice, 9, 1–40.https://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/JSSJ9_01_ENG.pdf. Accessed Mar 2020.

Smith, G. B. (2007). Developing sustainable food supply chains. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 363, 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2187

Souza, J. (2021). Como o racismo criou o Brasil. Estação Brasil

Starr, A., Martinez-Torres, M. E., & Rosset, P. (2011). Participatory democracy in action: Practices of the Zapatistas and the Movimento Sem Terra. Latin American Perspectives, 38(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X10384214

Tavernier, B. (2019). VRAC : Ensemble, on achète mieux ! Informations Sociales, 199, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.3917/inso.199.0080

Théry, H. (2017). São Paulo, du centre à la périphérie, les contrastes d’une mégapole brésilienne. EchoGéo, 41. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.15088

Thivet, D. (2012). Des paysans contre la faim. La ‘souveraineté alimentaire’, naissance d’une cause paysanne transnationale. Terrains & Travaux, 20, 69–85. https://doi.org/10.3917/tt.020.0069

Tiarajú d’Andrea, P. (2013). A formação dos Sujeitos Periféricos: Cultura e Política na Periferia de São Paulo. PhD Thesis, Department of Sociology, University of São Paulo

Tornaghi, C. (2016). Urban agriculture in the food-disabling city: (Re)defining urban food justice, reimagining a politics of empowerment. Antipode, 49(3), 781–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12291

Trauger, A. (2007). ‘Because they can do the work’: Women farmers in sustainable agriculture in Pennsylvania, USA. Gender Place & Culture A Journal of Feminist Geography, 11(2), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369042000218491

Visoni, C., & Nagib, G. (2019). Reappropriating urban space through community gardens in Brazil. Field Actions Science Reports, Special Issue, 20, 88–91.

Warshawsky, D. N. (2014). Civil society and urban food insecurity: Analyzing the roles of local food organizations in Johannesburg. Urban Geography, 35, 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.860753

Wegner, R., & Belik, W. (2012). Distribuição de hortifruti no Brasil: papel das Centrais de Abastecimento e dos supermercados. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 9(69), 195–220.

Funding

The funds for this research were donated by the UMR 8586 Prodig.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author, AP, contributed alone to the preparation of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

All interviewees were consulted prior to their interviews. Those who did not wish to give their names were anonymised.

Consent for publication

All interviewees agreed to appear in the publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.This article was translated from French to English by Laurent Chauvet, Sworn Translator (SATI) French-English & English-French.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Proust, A. Food justice and land justice in São Paulo: urban subsistence farming on the margins of the city. Rev Agric Food Environ Stud 103, 347–367 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-022-00180-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-022-00180-4