Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused widespread increase in stress and affected sleep quality and quantity, with up to 30% prevalence of sleep disorders being reported after the declaration of the pandemic. This study aimed to assess perceived changes due to the pandemic in the prevalence of insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in Korea, and identify the associated factors. An online survey was conducted among 4000 participants (2035 men and 1965 women) aged 20–69 years enrolled using stratified multistage random sampling according to age, sex, and residential area, between January, 2021 and February, 2022. The questionnaire included various items, such as socio-demographics, Insomnia Severity Index, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Insomnia was defined as difficulty falling asleep and difficulty maintaining sleep more than twice a week. EDS was classified as an ESS score ≥ 11. Insomnia was reported by 32.9% (n = 1316) of the participants (37.3% among women and 28.6% among men). Multivariate logistic regression revealed that insomnia was associated with female sex [odds ratio (OR) = 1.526, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.297–1.796], night workers (OR 1.561, 95% CI 1.160–2.101), and being unmarried (OR 1.256, 95% CI 1.007–1.566). EDS was reported by 12.8% (n = 510) of the participants (14.7% among men and 10.7% among women). EDS was associated with male sex (OR 1.333, 95% CI 1.062–1.674), and being employed (OR 1.292, 95% CI 1.017–1.641). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of insomnia increased in Korea, while there was no significant change in EDS compared with pre-pandemic evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep disturbances, especially insomnia and daytime sleepiness, are common among adults; they are associated with various physical disorders and accidents [1, 2]. The prevalence of insomnia in adults in Western countries reportedly ranges from 10 to 30% [3, 4]. In Korea, a nationwide telephone survey demonstrated an insomnia, which was defined as either experiencing difficulty falling asleep or returning to sleep after waking in the night more than twice a week, prevalence of 22.8% in individuals aged 20–69 years in 2009. Meanwhile, a face-to-face interview that used the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and defined insomnia as a score of 11 or higher, reported a prevalence of 10.8% among adults aged 19–69 years in 2012 [5, 6]. Furthermore, the prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) was 12.2% in individuals aged 40–69 years living in Ansan, Korea; habitual snoring or sleep-related problems reportedly increased the risk of EDS [7].

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that causes respiratory syndrome, has resulted in a pandemic with widespread increase in stress [8]. The pandemic phenomena has influenced sleep, and efforts to prevent the spread of the virus have disheveled our daily lives. These factors may affect sleep patterns, resulting in serious physical and mental health problems. Since the pandemic is a complex, multifaceted situation, it is necessary to investigate the potential changes in sleep patterns and how these patterns relate to the psychological response to the pandemic.

Early COVID-19 studies in Asia and Europe reported sleep disorders in up to one-third of the studied populations [9, 10]. In Korea, sleep surveys among medical staff at COVID-19 base hospitals have been conducted and reported that medical staff who worked in COVID-19 response teams had high levels of depression and anxiety and poor sleep quality; this was more severe in nurses than doctors [11]. However, sleep studies among the public have not been conducted yet in Korea. The present study aimed to assess perceived changes due to the pandemic in the prevalence of insomnia and EDS in the general public, and identify the factors associated with sleep changes during the outbreak.

Methods

Participants and survey procedure

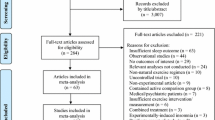

This study used the data from National Sleep Survey of South Korea 2022, a nationwide population based survey on sleep disturbances and public awareness. An online survey using a structured questionnaire was conducted from January, 2021 to February, 2022. A representative sample of 4,000 participants aged between 21 and 69 years were constituted using a stratified multistage random sampling method. The sample was established based on population of residence (capital and five Korean provinces), sex, age (five levels: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and 60–69 years), marital status, employment, working patterns, and monthly income. This survey was conducted by Embrain Public company on behalf of Epidemiology Committee of the Korean Sleep Research Society. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dongsan Medical Center (IRB No. 2021–12-063). All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

This study used a structured web-based questionnaire consisting of the following nine sections: demographics and health habits, health status associated with COVID-19, Internet/social media use, current sleep pattern, subjective sleep parameters, awareness of sleep disorders, sleep apnea syndrome and insomnia treatment, STOP questionnaire, modified Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and simple questions regarding restless legs syndrome. The outcome of interest was insomnia and EDS, measured using the modified ISI and ESS questionnaires in this study. The ISI includes seven items that evaluate difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, problems waking up too early, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily functions, noticeability of impairment attributed to sleep problems, and distress caused by the sleep problem [12]. We modified the answers for the first three questions (about the severity of the symptoms) to 1: < once a week; 2: once a week; 3: 2–4 times per week; 4: 5–6 times per week; and 5: daily. Criteria for insomnia was having difficulty falling asleep and difficulty maintaining sleep twice or more in a week. An ISI score ≥ 15 was considered as moderate to severe insomnia The ESS consists of questions on eight different sleep-related activities and situations to assess the likelihood of falling asleep or falling asleep in each situation [13]. An ESS score ≥ 11 was classified as EDS.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of cases by the total population. We analyzed the data using the chi-square test for categorical data. Logistic regression analysis was used to compute the relative risk of sociodemographic factors associated with insomnia and EDS symptoms, All reported p values are two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study population

The 4,000 participants comprised 2,035 (50.9%) men and 1,965 (49.1%) women, with 717 (17.9%), 717 (17.9%), 874 (21.8%), 924 (23.1%) and 768 (19.2%) of the participants aged 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and 60–69 years, respectively.

The residential areas were Seoul (19.2%), Gyeonggi/Gangwon (35.3%), Daejeon/Chungcheong (10.5%), Daegu/Gyeongbuk (9.5%), Busan/Gyeongnam (15%), and Gwangju/Jeonla/Jeju provinces (10.6%). Among the participants, 58.8% were married, 35.9% were unmarried, and 5.6% were divorced/widowed. Employed participants comprised 71.3%, while 28.7% were unemployed. Of those employed, 90.5% were daytime workers, 7.2% were shift workers, and 2.3% were night workers. The percentages of the participants with monthly incomes of < 1600, 1600–2399, 2400–3199, 3200–3999, 4000–4799, 4800–5599, and > 5600 United States dollar (USD) were 12.9%, 16.7%, 17.1%, 15.6%, 11.9%, 8.9%, and 16.9%, respectively (Table 1). The sex, age, economic status, and place-of-residence distributions of the study participants were representative of the general Korean adult population.

Prevalence of insomnia and associated characteristics

Of the 4,000 participants, 32.9% (n = 1316) complained of insomnia; the prevalence was significantly higher in women than in men (37.3% versus 28.6%, p < 0.001), across all age groups. Among men, the prevalence was the highest in those aged 20–29 years, while among women, it was in those aged 30–39 years, and showed a decreasing tendency with age (p < 0.001) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Difficulty initiating sleep, occurring more than twice a week, was reported by 25.6% of the participants (30.3% among women and 21.0% among men), with showing highest prevalence in their twenties (27.8% in men and 38.9% in women). Difficulty maintaining sleep occurred more than twice a week in 22.7% of the participants (25.1% among women and 20.3% among men). Among women, those in their thirties had the highest prevalence (29.7%), while among men, those in their sixties had the highest prevalence (24.0%) (Fig. 2). Moderate to severe insomnia was reported by 12.9% of the participants (13.9% among women and 11.9% among men). Among men, 20–29 years age group had the highest prevalence (16.2%), whereas among women, 60–69 years age group had the highest prevalence (13.6%) (Fig. 3).

The prevalence of insomnia decreased significantly with age (p < 0.001), peaking at 37.9% at 20–29 years of age, and was higher among unmarried individuals (38.1%, p < 0.001). Additionally, night workers (39.4, p = 0.013) and those with low monthly income (p = 0.030) showed significantly higher of insomnia compared with others; interestingly, it did not differ with the place of residence and employment status. Sleep latency and total sleep time were also showed significant correlation (Table 1).

Multivariate logistic regression revealed that the prevalence of insomnia was associated with being female (OR 1.526, p < 0.001), unmarried (OR 1.256, p = 0.043), night workers (OR 1.561, p = 0.003), smoking (OR 1.267, p = 0.04) (Table 2).

Additionally, 87 (6.6%) of the 1,316 participants with insomnia symptoms (2.2% of total participants) were currently being treated for insomnia. Further, Internet/social media was analyzed. High prevalence of Internet/social media use was characteristic of the younger age group, and 80% of the 4000 participants answered that watching digital media or TV before going to sleep interfered with sleep.

Prevalence of EDS

Among the 4000 participants, 510 (12.8%) complained of EDS, with higher prevalence in men (14.7%) than in women (10.7%, p < 0.001). Among both men and women, those in their thirties showed the highest EDS (15.3% and 20.0%) (Fig. 4). The prevalence of EDS decreased significantly with age (p < 0.001), peaking at 17.7% in individuals aged 30–39 years. Unmarried (16.0%, p < 0.001) and employed (13.8%, p = 0.011) individuals and those with lower income (p = 0.013) showed significantly higher EDS. However, it did not differ with the place of residence or working pattern. Additionally, alcohol consumption showed a significant correlaiton with EDS (33.5%, p < 0.001), sleep latency and total sleep time during weekday also had significant relationships (Table 1). Multivariate logistic regression revealed that the prevalence of EDS was negatively associated with 50–59 (OR 0.604, p = 0.007) and 60–69 (OR 0.672, p = 0.047) years age groups, and positively associated with male sex (OR 1.333, p = 0.013) and being employed (OR 1.292, p = 0.036) (Table 3).

Discussion

COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant psychological, social, and medical issues. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Korean general population.

The findings suggest that one in three adults (32.9%) has insomnia; difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep at least two nights per week occurred in 25.6% and 22.7% of the participants, respectively. Compared with previous findings in Korea in 2009 (22.8%) [5], overall insomnia increased by one and half times with COVID-19, and difficulty initiating sleep and maintaining sleep dramatically increased by three and two times, respectively.

Similar tendency for the increase could be seen in other countries. In an online survey in the Greek population during the COVID-19 pandemic, 37.6% of the participants scored above the cut-off for insomnia [10]. According to a study which conducted self-design questions related to the COVID-19 outbreak of 1563 participants in China, 36.1% participants had insomnia symptoms according to the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (total score ≥ 8) [14], also the prevalence rate of insomnia was consistent with 37% in Hong Kong during severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic [15]. Additionally, a systematic review and meta-analysis estimated insomnia prevalence during COVID-19 to be 38.9% [16], which is high compared to the prevalence of 10–30% before the pandemic [3, 4]. These results showed interesting aspects of the pandemic related to sleep health. Stress levels increased during the outbreak of the virus due to concerns about health, financial consequences, social life, and changes in daily living. Reduced physical fatigue, increased sunlight exposure, and increased use of electronic devices can also negatively affect sleep health.

The prevalence of insomnia increased more steeply in women, compared with a previous epidemiologic study in Korea [5]; additionally, women were found more vulnerable to depression, stressful incidents, post-traumatic stress, and psychological distress including anxiety [17, 18].

In addition, previous studies showed that the prevalence of insomnia increased with age [5], but in our study, it was confirmed that the prevalence of insomnia was high in people in their 20s and 30s. The authors assessed the reason for the high prevalence of insomnia among young people. First, the increase in telecommuting due to the pandemic may have caused insomnia due to reduced physical activity during the day. Second, it may be caused by economic difficulties due to job insecurity due to the pandemic. Lastly, the tendency to go to bed late due to excessive use of smartphones in bed may be the cause.

Interestingly, although 32.9% of the participants complained of insomnia, only 87 (6.6%) of the 1,316 participants with insomnia symptoms (2.2% of overall participants) were currently being treated for insomnia. Few studies have assessed the treatment rate of insomnia worldwide. According to a study using health insurance review and assessment service data in 2011, sedatives were prescribed to 1.5% of the general population [19]; therefore, on comparing with the increased prevalence after the pandemic, the treatment rate is still estimated to be low.

Treatment for insomnia includes sleep hygiene education, pharmacological treatments, and cognitive behavioral therapy. The reason why participants with symptoms of insomnia did not receive treatment could be attributed to several factors. First, the guidelines for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult to access medical care. Second, there was a fear of transmitting COVID-19 when visiting medical facilities. Third, the actual pandemic led to unemployment, which may have reduced the perceived need for treating insomnia, and lastly, the high prevalence of insomnia among young people may have led to a less serious perception of its risks and a lack of awareness of the need for treatment.

According to our results, the prevalence of insomnia and EDS is higher in younger age groups. These results are contrary to those of previous studies and may be interpreted as a special phenomenon related to the pandemic. There are several possible reasons why EDS is highly observed among young age groups. First, it is the increase in telecommuting due to the pandemic has led to an increase in daytime sleepiness, multivariate analysis suggests that the employed group is more likely to EDS compared to the unemployed group. Second, the decrease in outdoor activities due to social distancing measures among young people, prolonged indoor living, and increased mobile phone usage may lead to an increase in insomnia, which in turn could cause an increase in EDS the following day.The prevalence of EDS in Korea is 12.8%, and significantly higher in men (14.7%) than in women. These findings are consistent with previous studies in Korea and other countries [6, 20, 21]. Unlike insomnia, EDS was not significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic; previous studies have shown that EDS was predominantly affected by habitual snoring or sleep related problems [22].

The strengths of our study include the recruitment of a representative sample with a broad age range, and the use of validated questionnaires. However our study had several limitations. First, the diagnosis of insomnia did not conform to all of the diagnostic criteria for insomnia given in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. However, the two predominant components of insomnia, difficulty in initiating sleep and difficulty in maintaining sleep, were considered. Second, not all symptoms associated with insomnia, such as depression, anxiety, and memory impairment, were surveyed. Third, even if the study is representative of the Korean population considering most factors, due to the preference for healthy older adults in online surveys, the prevalence of insomnia and EDS may have been slightly lower compared to other studies. Additionally, young individuals who use more harmful media may have had a higher motivation to participate.

In conclusion, research on insomnia and EDS during the pandemic is scarce. Our study demonstrated an increased prevalence of insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women in their twenties and thirties, unmarried individuals, night workers, and those with low monthly incomes were more susceptible to insomnia. These findings may contribute to the management of insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in Asian populations. As insomnia is known to have adverse health effects, the aforementioned aspects need to be considered from a public health perspective.

References

Krakow B, Melendrez D, Ferreira E, et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2001;120(6):1923–9.

Becker PM. Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(4):855–vii.

Ohayon MM, Smirne S. Prevalence and consequences of insomnia disorders in the general population of Italy. Sleep Med. 2002;3(2):115–20.

Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7(2):123–30.

Cho YW, Shin WC, Yun CH, Hong SB, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia in Korean adults: prevalence and associated factors. J Clin Neurol. 2009;5(1):20–3.

Choi YH, Yang KI, Yun CH, Kim WJ, et al. Impact of insomnia symptoms on the clinical presentation of depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional population study. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 716097.

Joo S, Baik I, Yi H, Jung K, et al. Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness and associated factors in the adult population of Korea. Sleep Med. 2009;10(2):182–8.

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):57.

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2): e100213.

Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, Papadopoulou K, et al. Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289: 113076.

Kwon DH, Hwang JH, Cho YW, Song ML, et al. The mental health and sleep quality of the medical staff at a Hub-Hospital against COVID-19 in South Korea. J Sleep Med. 2020;17(1):93–7.

Cho YW, Song ML, Morin CM. Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. J Clin Neurol. 2014;10(3):210–5.

Cho YW, Lee JH, Son HK, Lee SH, et al. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(3):377–84.

Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease Outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;14(11):306.

Lee S, Chan LY, Chau AM, Kwok KP, et al. The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):2038–46.

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7.

Kawada T, Yosiaki S, Yasuo K, Suzuki S. Population study on the prevalence of insomnia and insomnia-related factors among Japanese women. Sleep Med. 2003;4(6):563–7.

Li SH, Graham BM. Why are women so vulnerable to anxiety, trauma-related and stress-related disorders? The potential role of sex hormones. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):73–82.

Chung S, Park B, Yi K, Lee J. Pattern of hypnotic drug prescription in South Korea: health insurance review and assessment service-national sample. Sleep Med Res. 2013;4(2):51–5.

Hayley AC, Williams LJ, Kennedy GA, Berk M, et al. Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness in a sample of the Australian adult population. Sleep Med. 2014;15(3):348–54.

Soldatos CR, Allaert FA, Ohta T, Dikeos DG. How do individuals sleep around the world? Results from a single-day survey in ten countries. Sleep Med. 2005;6(1):5–13.

Gottlieb DJ, Whitney CW, Bonekat WH, Iber C, et al. Relation of sleepiness to respiratory disturbance index: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(2):502–7.

Acknowledgements

This study was a project under the National Sleep Survey of South Korea 2022 supported by the Korean Sleep Research Society.

Funding

No funding was received in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This is not an industry supported study. None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dongsan Medical Center (IRB No. 2021-12-063). All participants provided written informed consent.

Research involving human and animal participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, JY., Kim, K.T., Lee, SY. et al. Insomnia during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Korea: a National sleep survey. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 21, 431–438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-023-00464-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-023-00464-2