Abstract

The high prevalence of mental disorders in university students emphasizes the need to explore contributing factors. While socioeconomic position affects mental health in the general population, it is crucial to investigate if the same applies to university students. MEDLINE-Ovid, Embase-Ovid and PsycINFO databases were searched. All original peer-reviewed observational studies quantifying the association between socioeconomic position and depression, anxiety or eating disorders were included without language or date restrictions. After initial screening, eligible studies were selected, data was extracted using a spreadsheet, and their quality was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. The results were synthesized narratively. Seventy-eight of 20,465 records identified were included. Most studies were published in English and originated from high and upper-middle-income countries. The most common socioeconomic indicators were family socioeconomic status/class, financial stress, and parental education. Most studies found a positive association between socioeconomic indicators and depressive and anxiety symptoms, but not eating disorders. The quality of the studies was mixed, with a small proportion using validated measurement tools and appropriate sample sizes. This study highlights the importance of measuring socioeconomic position accurately and applying new methods that can reveal the causal pathways and interactions of multiple identities that shape mental health disparities for the university student population.

Preregistration A protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022247394).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high prevalence of mental health issues among university students, potentially exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, underscores the need to understand factors that may contribute to this vulnerability. Previous studies indicate that a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors may be responsible for mental health outcomes in university students (Byrd & McKinney, 2012; Liu et al., 2019), but it remains unclear if socioeconomic position (SEP) is associated with depressive, anxiety symptoms or eating disorders (ED). The current study examines the relationship between socioeconomic position and depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and eating disorders in university students. The aims are to review studies on the link between socioeconomic position and common mental disorders and eating disorders, and to evaluate if socioeconomic position predicts a higher risk of developing these disorders during university.

The prevalence of mental disorders such as depressive symptoms is higher among university students compared to the general population or non-university students. Most university students are in the emerging adulthood period, this life course stage coincides with the onset of anxiety, depressive symptoms and eating disorders (Arnett, 2007; Beesdo et al., 2010; Potterton et al., 2020). Moreover, the prevalence of mental health problems among university students appears to be increasing (Acharya et al., 2018). This growing issue is especially relevant from a public health perspective, considering the sustained increase in enrollment of students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds in higher education (UNESCO, 2017).

Furthermore, university students have been identified as a population that may be at increased risk for mental health problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to some studies, university students had the highest pooled prevalence of depression (Yuan et al., 2022) and anxiety (Yuan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022) compared to healthcare workers and the general population. In addition, many systematic reviews report an increase in common mental disorders in this population during the pandemic (Deng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liyanage et al., 2021).

Socioeconomic position is an aggregate concept encompassing resource-based and prestige-based measures. Resource-based measures refer to material and social resources such as income, wealth, and education; terms describing inadequate resources include "poverty" and "deprivation." Prestige-based measures refer to one's social hierarchy rank or status, typically evaluated by access to goods, services, knowledge, and occupational prestige, income, and education. Socioeconomic position can be measured at the individual, household, and neighborhood level (Krieger et al., 1997) and some measurement of socioeconomic position can be more adequate for different stages of the life course (Galobardes et al., 2006a, 2006b).

Low socioeconomic position are associated with various social and health problems (Marmot & Bell, 2012), including higher levels of common mental disorders such depression (Lorant et al., 2003; Lund et al., 2018; Ridley et al., 2020) and anxiety (Lund et al., 2018; Ridley et al., 2020) in the general population. However, studies on eating disorders (anorexia, bulimia and binge eating) have found these conditions present across socioeconomic backgrounds, with no consistent evidence that eating disorders are diseases of affluence in the general population (Huryk et al., 2021). Some studies specifically among university students though have found that those of lower socioeconomic status had a greater prevalence of positive eating disorders screens compared to those of higher socioeconomic status (Burke et al., 2023).

Current Study

Many research studies have examined the association between measures of socioeconomic position and mental health outcomes in the general population. However, the relationship between socioeconomic position and specific mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders has not been systematically reviewed in university students, even though this is a population at increased risk for developing these mental health problems. Given the increased vulnerability of university students, a systematic review investigating the links between measures of socioeconomic position and depressive symptoms, anxiety, and eating disorders in this group is timely. This systematic review aims to synthesize the existing evidence on the relationship between socioeconomic position and depressive, anxiety symptoms and eating disorders in university students. The first objective is to review studies examining associations between socioeconomic position and common mental disorders and eating disorders among university students, and the second objective is to evaluate the evidence on whether socioeconomic position is a longitudinal predictor for the increased risk of developing mental illness during university.

Methods

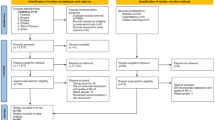

A protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022247394). Procedures for this systematic review were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). A PRISMA checklist is included in Online Resource 1.

Eligibility Criteria

To be included, studies needed to fulfil these criteria: a) be published in a peer-reviewed journal article; b) constitute an original peer-reviewed observational study (cross-sectional, case–control and cohort); c) Include undergraduate students population, without distinction of sex, nationality, ethnicity or field of study d) Papers including at least one of the following outcomes: common mental disorders (depressive and anxiety symptoms) and eating disorders (binge eating, anorexia and bulimia); the outcomes specified above must have been assessed with validated instruments based on the subjective report of the same participants (i.e., self-administered questionnaires) or trained observers (i.e., clinical interviews); e) The article explicitly states to estimate the association of socioeconomic position with at least one of these outcomes separately and to quantify these relationships. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the scientific literature, a broad definition of SEP was used, including individual, family or area level. No language or time restrictions were applied.

Articles were excluded if: (a) participants are students of secondary education, vocational or technical school; (b) include only participants with a medical condition or disability; (c) studies that combined both undergraduate and postgraduate students and where data was not stratified for undergraduate students alone; (d) clinical trials of any kind; (e) socioeconomic position was only included as an adjustment in the model.

Search

Embase, MEDLINE (Ovid interface), EMBASE (Ovid interface) and PsycINFO (OVID interface) were searched from inception to April 12th, 2022, for peer-reviewed journal articles fitting the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The search followed these broad themes: "university students" AND "mental disorders" AND socioeconomic position", including subject headings and synonyms of each included keyword. Full details of the search strategy can be found in Online Resource 2.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts of articles were screened in full by one reviewer (SM). Four reviewers (DL, IL, CC, EM) additionally screened a 40% sample of the records. To ensure good calibration in screening, all reviewers screened the same 50 articles before starting the process and disagreements were reviewed. During the screening process, meetings were established every two weeks to resolve queries from the reviewers. Full texts of abstracts included by any author at this stage were then reviewed against inclusion criteria (SM, DL, IL, CC, EM), and 50% were checked by a second reviewer (SM). A third reviewer (MP) was consulted in case of any disagreements. Screening of records and selected studies were handled using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). To ensure the reliability of our data extraction process, inter-rater agreement was assessed using Cohen's Kappa (κ) statistic. The kappa coefficient for the inter-rater agreement was found to be κ = 0.62 for the title and abstract and κ = 0.79 for the full-text screening, indicating substantial agreement beyond what would be expected by random chance. All disagreements were solved via consensus.

Data Extraction

A data extraction sheet was developed, pilot-tested on five randomly selected eligible studies and refined accordingly. Two authors independently extracted data from selected studies (SM, DL, IL, CC, EM) and entered them into an electronic spreadsheet (see Online Resource 3). All data entries were compared between authors, and disagreements were solved by discussing with a third author (MP). Information extracted included: Study name, country, study design, survey year, before or during the COVID-19 pandemic, sampling technique, sample size, response rate, the proportion of female participants, mean age, student's field of study, socioeconomic position, outcomes, and instruments used, crude and adjusted statistics, confidence intervals (CIs), covariates, p-values and direction of the association.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS; (Wells et al., 2014); this scale uses eight items, categorized into three domains of potential bias (selection of study group, comparability of the groups and the ascertainment of the exposure/outcome). Two NOS versions were used: NOS for cohort studies and one modified for cross-sectional studies (Herzog et al., 2013). The modified scale assessed study quality based on eight domains, including (1) sample representativeness (inclusion of all subjects or use of random sampling), (2) sample size (justified and satisfactory), (3) non-respondents (Comparability between respondents and non-respondents, and satisfactory response rate), (4) valid measurement tools (validated or described), (5) study controls by gender, (6) study controls by age, and (7) assessment of the outcome (appropriate and clearly described statistical tests). The overall quality score ranged from 0 to 5 for selection (4 first domains), 0–2 for comparability (5 and 6 domains), and 0–3 for outcome (7 and 8 domains). Two authors independently evaluated the risk of bias and entered them into an electronic spreadsheet (SM, DL, IL, CC, EM).

Synthesis of the Results

A narrative and structured synthesis of the data of the included studies was carried out. Study characteristics (study design, country, country income group, instruments, sampling technique, conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic) and results were tabulated to facilitate the presentation of the information and compare patterns.

The studies were stratified by poverty indicator, mental disorder, and those that conducted the unadjusted and adjusted analysis. Using these stratifications, the percentage of studies that showed positive, null, and negative relationships between categories of socioeconomic position (individual, family, and area /neighborhood level) and mental disorder variables was determined.

Results

Of the 20,465 records obtained, 20,110 were excluded after screening titles and abstracts, and the full texts of 329 manuscripts were reviewed for eligibility. Seventy-eight articles were included in the narrative synthesis. Most excluded articles were because they did not quantify the association between a socioeconomic variable and a mental health outcome (N = 58) or because they did not report an effect size (N = 52). The entire selection process is presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of our included studies are tabulated in Table 1. Most of the studies were published in English (95%). The publication period ranged from 2004 to 2022; 46% of the studies were published during the last three years (2020 to 2022), and 16 (21%) were explicitly conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Most of the studies were carried out in Asia (36%), followed by Europe (24%), and 76% were conducted in high and upper-middle-income countries. Most studies originated from China (n = 14), followed by the United States (n = 10), Turkey (n = 5) and the United Kingdom (n = 4).

All studies adopted a cross-sectional design except for two studies using a longitudinal design (Richardson et al., 2015, 2017). The included studies' median number of students with valid responses was 739 (range 97–96,376), with a median female representation of 64% (range 28.1–100%). The median response rate to the survey was 83%; the range was 9.8% to 100% within the studies that reported the response rate. Most of the studies used a convenience sample (42%), followed by studies using random samples (37%) and census sampling (21%). Furthermore, 41 studies collected data from a sample of a mixed field of students, while medical, nursing and dental were targeted in 17, 9 and 3 studies, respectively.

Mental Disorders Measures

Sixty-two studies evaluated depressive symptoms, 26 anxiety symptoms and nine eating disorders. Various tools were used to evaluate mental disorders. For depressive symptoms, the most common scale was Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI/BDI-II, n = 15), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, n = 13) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9, n = 12). For anxiety symptoms, was the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7, n = 9) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 (DASS-2, n = 8), and for eating disorders, was the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26, n = 5). Only one study used clinical interviews with diagnoses (Chen et al., 2013).

Socioeconomic Position Measures

A total of 127 socioeconomic indicators were used across the 78 studies (Table 2 and Online Resource 4). The most used indicator was family socioeconomic status/class (n = 23), followed by household income (n = 20) and financial stress (n = 19). There was variation in the number of measures studied, with 49 studies using one indicator, 18 using two, and 11 using three or more. Only 30 (23%) of the total indicators used standardized or validated measurements. Sixty measurements were described in the methods but were not validated, and 37 indicators were not described in any study section.

Cross-Sectional Associations Between SEP and Mental Disorders

Most studies found a positive association, in which lower socioeconomic position is related to higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, but not eating disorders. Using unadjusted and adjusted analysis, the percentage of studies showing a positive association for depressive symptoms was 78% and 63%, respectively, whereas for anxiety symptoms, it was 50% and 64%. Regarding eating disorders, 60% and 45% reported no associations, respectively (see Table 3).

Socioeconomic Position and Depressive Symptoms.

In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the indicators most consistently positively associated with depressive symptoms were mother's education, household income, family socioeconomic status/class, and financial stress. Father's education/higher education of one parent showed a positive association with depressive symptoms in unadjusted models (6 of 7 studies); however, in the unadjusted models when other variables were controlled for in multivariable analysis, most associations (10 of 13 studies) were non-significant. A similar tendency occurred with parental employment (father or mother), where significant associations dropped in adjusted models.

A few studies (n = 4) explored the association between depressive symptoms and area /neighborhood level or food insecurity variables. Except for one study that showed a negative correlation between the number of persons per room and depressive symptoms in the adjusted model (Ibrahim et al., 2012), most studies reported a positive association between a lower socioeconomic position and depressive symptoms. The variable disposable income/pocket money has a positive association for 3 of 4 studies in adjusted models.

Socioeconomic Position and Anxiety Symptoms.

The association between socioeconomic indicators and anxiety symptoms showed more variation compared to depressive symptoms, with 50% of unadjusted models and 64% of adjusted models showing a positive association. There were also fewer studies exploring anxiety symptoms compared to depressive symptoms in both unadjusted (14 vs. 49) and adjusted (25 vs. 78) models. Studies investigating mother's education (n = 2) and mother's employment (n = 1) consistently found positive associations across all models, meaning lower SEP was associated with higher anxiety symptoms. Similarly, family socioeconomic status/class (4 of 6 adjusted studies) and household income (4 of 6 unadjusted, 2 of 4 adjusted studies) also showed a positive association between lower SEP and higher anxiety symptoms.

There was no clear association between anxiety symptoms and first-generation students or father's education. Moreover, the few studies on food insecurity (n = 3) and housing/overcrowding (n = 1) found significant positive relationships with anxiety symptoms. Unlike with depressive symptoms, most studies found no association between financial stress and anxiety symptoms (2 of 3 unadjusted, 3 of 5 adjusted).

Socioeconomic Position and Eating Disorders.

The evidence for an association between eating disorders and socioeconomic position indicators was inconclusive, with mixed findings. Across unadjusted and adjusted models, 50% of associations were null, 25% positive, and 25% negative. One study found a bidirectional relationship between family socioeconomic status/class and eating disorders, meaning both high and low socioeconomic status were eating disorder risk factors compared to medium socioeconomic status (Ünsal et al., 2010).

Longitudinal Associations Between SEP and Mental Disorders

Only 2 studies report longitudinal associations between SEP and mental disorders. Richardson et al. (2017) found greater financial difficulties predicted worsening anxiety at 3–4 months, while anxiety predicted worsening finances, implying a bidirectional relationship. The authors did not find a longitudinal link between economic difficulties and depression, or between depression, anxiety, and family affluence.

On the other hand, other longitudinal study found greater baseline financial difficulties and lower family affluence independently predicted more severe eating attitudes up to a year later after controlling for baseline eating attitudes and demographics. When examined by gender, these relationships were only significant for women. (Richardson et al., 2015).

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Table 4 and Online Resource 5 include the NOS assessment findings. Study quality was mixed. For cross-sectional studies, the mean selection quality score was 2.2 out of 5, though 10 of 76 studies scored 4 or higher. Only 18.4% used validated exposure measures, and 65.8% lacked appropriate or justifiable sample sizes. Regarding comparability, 38.2% did not adjust for age and gender, while 36.8% adjusted for both. All but one study (Chen et al., 2013) used self-report versus blinded clinical outcome measures. Exposure-outcome association measurement was adequate and clear in 61.8% of articles. The two articles with longitudinal design had higher quality, with NOS scores of 4, 2, and 2 across the three dimensions.

Discussion

Although university students are a population at high risk for mental disorders such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders (ED), there remains a gap in understanding which risk factors produce an increased vulnerability in this group. This study focused on examining the association and predictive role of socioeconomic position variables with three key mental health outcomes among university students: depressive, anxiety symptoms, and ED. Exploring the effects of socioeconomic position on these mental health outcomes could help identify factors that put certain groups of students at greater risk. This can inform targeted interventions and programs aimed at addressing potential mental health disparities among university students based on socioeconomic position.

Most research found a significant positive association (lower SEP with higher levels of mental disorders) between socioeconomic position variables and depressive and anxiety symptoms, but findings were mixed for eating disorders. The indicators with the most consistently positive associations with depressive symptoms was the mother's education. These results underscore the importance of future research considering the measurement of parental education separately and not as a single variable where only the most educated parent is considered. In addition, most studies found no association between financial stress and anxiety, contrary to what one would expect, and thus warrant further investigation. Regarding eating disorders, there was no discernible relationship with any indicator of socioeconomic position. These results are consistent with other studies addressing this phenomenon in clinical and general settings (Mitchison & Hay, 2014), and reinforce that the stereotype that eating disorders are a disease of affluence is baseless. Furthermore, some studies indicate that, while higher socioeconomic position does not predict illness, it does predict higher rates of treatment seeking among students who are ill (Sonneville & Lipson, 2018). As a result, it is central to develop more equitable and accessible treatment options for university students with eating disorders.

Limitations of the Studies

There are several limitations in the studies selected for this systematic review that may affect the interpretation of the results. First, given the high heterogeneity of outcome measures and predictors and control variables, it was inadequate to perform a meta-analysis, which limits the study's conclusions regarding the effect size of the associations reported. Second, because studies demonstrating a positive association are more likely to be published than those showing null associations, publication bias may have played a role in the results of this review (Dwan et al., 2008). Third, the control variables used in the multiple regression models were very heterogeneous, and only some studies presented unadjusted associations, making comparing results more challenging. Forth, the vast majority of the studies found were cross-sectional, which hindered possible interpretations of causal mechanisms of socioeconomic position measures with the examinate mental disorders.

Finally, while most studies provided a detailed description of the instruments for measuring mental health outcomes, the same did not apply to socioeconomic variables. Less than a quarter of the indicators used previously validated instruments and about a third of the studies did not provide any documentation on the conceptualization and measurement of socioeconomic indicators. Furthermore, none of the studies presented instruments specifically designed for the student population. This lack of accountability or paucity of critical thinking about how socioeconomic position is understood and operationalized in mental health research is consistent with previous literature investigating the association between poverty and mental disorders in the general population (Cooper et al., 2012).

Limitations of the Current Review

This review has some limitations. Firstly, the study focused only on articles published in peer-reviewed journals; due to a limitation of time and the large number of articles no systematic review of the grey literature was conducted, excluding grey literature may introduce publication bias, that may affect the validity and generalizability of the systematic review findings. Furthermore, even though the review included three important and comprehensive databases on the subject, the restriction to only these datasets raise the possibility that some studies may have been missed. This limitation stems from the potential exclusion of pertinent studies that may be indexed in databases beyond the scope of our selection. Lastly, due to limited capacity, this review only examined depressive, anxiety symptoms, and eating disorders, leaving out other prevalent mental health issues in this population, such as alcohol and other substance use disorders.

Future Research

According to the results of this research, there is much room for improvement in measuring socioeconomic indicators for mental health research. The existing measures often fail to capture the complex and multidimensional nature of poverty, resulting in an incomplete or inaccurate understanding of the association with mental disorders and a lack of comparability between studies. Therefore, there is a need to develop more comprehensive and relevant measures to assess socioeconomic position in the context of university students' mental health. Such measures would help researchers better understand the relationship between mental health and socioeconomic position in this population and help policymakers and universities design cost-effective interventions focused on at-risk populations to address this pressing issue.

In addition, when measuring socioeconomic position, it is essential to consider the unique characteristics of university students, as traditional measures used in the general population may not accurately reflect their level of privilege or disadvantage. This population faces specific risk factors that require targeted interventions. The stress and strain of the university experience, coupled with academic performance demands, can contribute to aggregate inequities in mental health outcomes. Therefore, it is essential to develop appropriate measures to help identify at-risk populations that may benefit from university mental health support programs. By doing so, it can be promoted that all university students have equal opportunities to achieve their full academic potential while maintaining good mental health.

On the other hand, it would be beneficial to incorporate new methodologies for analyzing mental health disparities in university students. Most studies used unadjusted or adjusted linear or logistic regressions to assess associations between socioeconomic position and mental disorders. This approach ignores the fact that people have multiple identities or social positions. The intersectional approach is a framework that recognizes the complex and intersecting nature of social identities and discrimination experiences. This approach considers the unique experiences of individuals who may face discrimination on multiple grounds, such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status (Collins, 2015). Researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of how multiple identities intersect to produce health and wellbeing inequalities by applying this approach to the study of socioeconomic disparities in university students. Methods such as a multilevel approach (Evans et al., 2018), latent class analysis (Goodwin et al., 2018) could be used by researchers to analyze associations between the various identities and discrimination experiences that individuals may face, as well as how these experiences intersect to produce inequalities. Mediation analysis (MacKinnon, 2012) could also be used to understand pathways and explore the underlying mechanisms through which socioeconomic position affects mental disorders.

Finally, the vast majority of the studies in this review were cross-sectional. Future researchers should prioritize using longitudinal methodologies to determine whether socioeconomic position is a risk factor for developing mental illness during university studies.

Conclusion

Research on factors associated with mental health outcomes in university students has increased in recent years also in light of the covid-19 pandemic. In this context a review that evaluates systematically the association and predictive role of socioeconomic position and mental health outcomes is timely. This review examines the evidence on how socioeconomic position variables are related to three mental health outcomes: depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and eating disorders. The review shows that most of the studies found a positive association between socioeconomic position and depressive and anxiety symptoms, meaning that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to have more mental health problems. However, the association between socioeconomic position and eating disorders was not consistent across studies. The review also identifies some limitations in the measurement and analysis of socioeconomic factors in this population.

Data availability

All project data are provided in the online supplementary materials.

References

Acharya, L., Jin, L., & Collins, W. (2018). College life is stressful today—Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of American College Health, 66(7), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1451869

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x

Beesdo, K., Pine, D. S., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2010). Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.177

Burke, N. L., Hazzard, V. M., Schaefer, L. M., Simone, M., O’Flynn, J. L., & Rodgers, R. F. (2023). Socioeconomic status and eating disorder prevalence: At the intersections of gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity. Psychological Medicine, 53(9), 4255–4265. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001015

Byrd, D. R., & McKinney, K. J. (2012). Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.584334

Chen, L., Wang, L., Qiu, X. H., Yang, X. X., Qiao, Z. X., Yang, Y. J., & Liang, Y. (2013). Depression among Chinese university students: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e58379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058379

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Cooper, S., Lund, C., & Kakuma, R. (2012). The measurement of poverty in psychiatric epidemiology in LMICs: Critical review and recommendations. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1499–1516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0457-6

Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Silver, Z., Wong, C. Y., Chang, O., Drakos, A., Zuo, Q. K., & Huang, E. (2021). The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 301, 113863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113863

Dwan, K., Altman, D. G., Arnaiz, J. A., Bloom, J., Chan, A.-W., Cronin, E., Decullier, E., Easterbrook, P. J., Von Elm, E., & Gamble, C. (2008). Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE, 3(8), e3081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003081

Evans, C. R., Williams, D. R., Onnela, J.-P., & Subramanian, S. (2018). A multilevel approach to modeling health inequalities at the intersection of multiple social identities. Social Science & Medicine, 203, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.011

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., & Lynch, J. W. (2006a). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(2), 95.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., Lynch, J. W., & Smith, G. D. (2006b). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(1), 7–12.

Goodwin, L., Gazard, B., Aschan, L., MacCrimmon, S., Hotopf, M., & Hatch, S. (2018). Taking an intersectional approach to define latent classes of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and migration status for psychiatric epidemiological research. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(6), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000142

Herzog, R., Álvarez-Pasquin, M., Díaz, C., Del Barrio, J. L., Estrada, J. M., & Gil, Á. (2013). Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-154

Huryk, K. M., Drury, C. R., & Loeb, K. L. (2021). Diseases of affluence? A systematic review of the literature on socioeconomic diversity in eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 43, 101548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101548

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., & Glazebrook, C. (2012). Analysis of an Egyptian study on the socioeconomic distribution of depressive symptoms among undergraduates. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(6), 927–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0400-x

Krieger, N., Williams, D. R., & Moss, N. E. (1997). Measuring social class in US public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health, 18(1), 341–378.

Li, Y., Wang, A., Wu, Y., Han, N., & Huang, H. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119

Liu, Y., Zhang, N., Bao, G., Huang, Y., Ji, B., Wu, Y., Liu, C., & Li, G. (2019). Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 244, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.084

Liyanage, S., Saqib, K., Khan, A. F., Thobani, T. R., Tang, W. C., Chiarot, C. B., AlShurman, B. A., & Butt, Z. A. (2021). Prevalence of Anxiety in University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010062

Lorant, V., Deliège, D., Eaton, W., Robert, A., Philippot, P., & Ansseau, M. (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(2), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf182

Lund, C., Brooke-Sumner, C., Baingana, F., Baron, E. C., Breuer, E., Chandra, P., Haushofer, J., Herrman, H., Jordans, M., & Kieling, C. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic review of reviews. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9

MacKinnon, D. (2012). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge.

Marmot, M., & Bell, R. (2012). Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health, 126(Suppl 1), S4-s10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014

Mitchison, D., & Hay, P. J. (2014). The epidemiology of eating disorders: genetic, environmental, and societal factors. Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S40841

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., ... Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Potterton, R., Richards, K., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2020). Eating disorders during emerging adulthood: A systematic scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3062. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03062

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., Roberts, R., & Jansen, M. (2017). A Longitudinal Study of Financial Difficulties and Mental Health in a National Sample of British Undergraduate Students. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., Waller, G., & Bell, L. (2015). Longitudinal relationships between financial difficulties and eating attitudes in undergraduate students. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(5), 517–521. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22392

Ridley, M., Rao, G., Schilbach, F., & Patel, V. (2020). Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms. Science, 370(6522), eaay0214. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay0214

Sonneville, K., & Lipson, S. (2018). Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(6), 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22846

UNESCO. (2017). Six ways to ensure higher education leaves no one behind (UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, Issue. http://en.unesco.org/gem-report/six-ways-ensure-higher-education-leaves-no-one-behind

Ünsal, A., Ayranci, Ü., Arslan, G., Tozun, M., & Çalik, E. (2010). Connection between eating disorders and depression among male and female college students in Kutahya. Turkey Alpha Psychiatry, 11, 112–119.

Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2014). Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. University of Ottawa.

Yuan, K., Zheng, Y. B., Wang, Y. J., Sun, Y. K., Gong, Y. M., Huang, Y. T., Chen, X., Liu, X. X., Zhong, Y., Su, S. Z., Gao, N., Lu, Y. L., Wang, Z., Liu, W. J., Que, J. Y., Yang, Y. B., Zhang, A. Y., Jing, M. N., Yuan, C. W., ... Lu, L. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of and risk factors associated with depression, anxiety and insomnia in infectious diseases, including COVID-19: A call to action. Mol Psychiatry, 27(8), 3214–3222. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01638-z

Zhang, S. X., Batra, K., Xu, W., Liu, T., Dong, R. K., Yin, A., Delios, A. Y., Chen, B. Z., Chen, R. Z., Miller, S., Wan, X., Ye, W., & Chen, J. (2022). Mental disorder symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci, 31, e23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000767

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor of the Adolescent Research Review for their helpful feedback.

Funding

This work was funded by ANID – Millennium Science Initiative Program – NCS2021_081. SM is funded by the National Agency of Research and Development (ANID) – Doctoral Scholarship Abroad Becas Chile, call 2019, folio 72200092. DL is funded by ANID – National Doctoral Scholarship, call 2020, folio 21200952.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM conceived the study, lead the design, participated in searching, screening and data analysis, coordination and interpretation of the results of the study, and drafted the manuscript; DL participated in searching, screening and data analysis; IL participated in searching, screening and data analysis; EM participated in searching, screening and data analysis; CC participated in searching, screening and data analysis; RA participated in protocol design, drafting and revision of manuscript; MP participated in protocol design, screening and data analysis, drafting and revision of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mac-Ginty, S., Lira, D., Lillo, I. et al. Association Between Socioeconomic Position and Depression, Anxiety and Eating Disorders in University Students: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00230-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00230-y