Abstract

Medical mistrust is associated with poor health outcomes, ineffective disease management, lower utilization of preventive care, and lack of engagement in research. Mistrust of healthcare systems, providers, and institutions may be driven by previous negative experiences and discrimination, especially among communities of color, but religiosity may also influence the degree to which individuals develop trust with the healthcare system. The Black community has a particularly deep history of strong religious communities, and has been shown to have a stronger relationship with religion than any other racial or ethnic group. In order to address poor health outcomes in communities of color, it is important to understand the drivers of medical mistrust, which may include one’s sense of religiosity. The current study used data from a cross-sectional survey of 537 Black individuals living in Chicago to understand the relationship between religiosity and medical mistrust, and how this differs by age group. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data for our sample. Adjusted stratified linear regressions, including an interaction variable for age group and religiosity, were used to model the association between religiosity and medical mistrust for younger and older people. The results show a statistically significant relationship for younger individuals. Our findings provide evidence for the central role the faith-based community may play in shaping young peoples’ perceptions of medical institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data are available upon request from the NIH COVID RADx Data Hub.

References

Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):79–85.

Bogart LM, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(2):200–7.

Hammond WP. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;45(1–2):87–106.

Kinlock BL, et al. High levels of medical mistrust are associated with low quality of life among black and white men with prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2017;24(1):72–7.

Street RL Jr, et al. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301.

Pellowski JA, et al. The differences between medical trust and mistrust and their respective influences on medication beliefs and ART adherence among African-Americans living with HIV. Psychol Health. 2017;32(9):1127–39.

LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146–61.

Adams LB, et al. Medical mistrust and colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. J Community Health. 2017;42(5):1044–61.

Powell W, et al. Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among African-American Men. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):102–17.

Kolar SK, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge and attitudes, preventative health behaviors, and medical mistrust among a racially and ethnically diverse sample of college women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(1):77–85.

Nguyen BT, et al. “I’m not going to be a guinea pig:” Medical mistrust as a barrier to male contraception for Black American men in Los Angeles CA. Contraception. 2021;104(4):361–6.

Irving MJ, et al. Factors that influence the decision to be an organ donor: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(6):2526–33.

Rego F, et al. The influence of spirituality on decision-making in palliative care outpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):22.

Moore D, Mansfield LN, Caviness-Ashe N. The role of black pastors in disseminating COVID-19 vaccination information to Black communities in South Carolina. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):8926.

Kiser M, Lovelace K. A national network of public health and faith-based organizations to increase influenza prevention among hard-to-reach populations. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):371–7.

Hill PC, Hood R. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press; 1999.

Li S, et al. Religious service attendance and lower depression among women—a prospective cohort study. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(6):876–84.

VanderWeele TJ, et al. Association between religious service attendance and lower suicide rates among US women. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(8):845–51.

Benjamins MR, et al. Religion and preventive service use: do congregational support and religious beliefs explain the relationship between attendance and utilization? J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):462–76.

Kim ES, VanderWeele TJ. Mediators of the association between religious service attendance and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(1):96–101.

Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality A systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):81–90.

Roberts L, Ahmed I, Hall S, Davison A. Intercessory prayer for the alleviation of ill health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(2):CD000368. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000368.pub3

Park CL, Wortmann JH, Edmondson D. Religious struggle as a predictor of subsequent mental and physical well-being in advanced heart failure patients. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):426–36.

Brewer LC, Williams DR. We’ve come this far by faith: the role of the black church in public health. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):385–6.

Pew Research Center. Attendance at religious services by race/ ethnicity—religion in America: U.S. religious data, demographics and statistics. 2020 September 29, 2023]; Available from: https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/compare/attendanceat-religiousservices/by/racial-and-ethnic-composition/

Turner N, Hastings JF, Neighbors HW. Mental health care treatment seeking among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: what is the role of religiosity/spirituality? Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(7):905–11.

Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: exploring variations by race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(6):S332–47.

Ferraro KF, Kim S. Health benefits of religion among Black and White older adults? Race, religiosity, and C-reactive protein. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:92–9.

Steffen PR, et al. Religious coping, ethnicity, and ambulatory blood pressure. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):523–30.

Butler JZ, et al. COVID-19 vaccination readiness among multiple racial and ethnic groups in the San Francisco Bay Area: a qualitative analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0266397.

Sutton MY, Parks CP. HIV/AIDS prevention, faith, and spirituality among Black/African American and Latino communities in the United States: strengthening scientific faith-based efforts to shift the course of the epidemic and reduce HIV-related health disparities. J Relig Health. 2013;52(2):514–30.

Jones DG. Religious concerns about COVID-19 vaccines: from abortion to religious freedom. J Relig Health. 2022;61(3):2233–52.

Benjamins MR. Religious influences on trust in physicians and the health care system. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):69–83.

López-Cevallos DF, Flórez KR, Derose KP. Examining the association between religiosity and medical mistrust among churchgoing Latinos in Long Beach. CA Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(1):114–21.

Bengtson VL, et al. Does religiousness increase with age? Age changes and generational differences over 35 years. J Sci Study Relig. 2015;54(2):363–79.

Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore JA. Religious consolation among men and women: do healthproblems spur seeking? J Sci Study Relig. 2000;39(2):220–34.

Idler EL, McLaughlin J, Kasl S. Religion and the quality of life in the last year of life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(4):528–37.

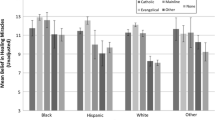

Boulware LE, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358–65.

Quinn KG, Hunt BR, Jacobs J, Valencia J, Voisin D, Walsh JL. Examining the relationship between anti-black racism, community and police violence, and COVID-19 vaccination. Behav Med. 2023;14:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2023.2244626. Epub ahead of print.

Shelton RC, et al. Validation of the group-based medical mistrust scale among urban black men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):549–55.

Cummings JP, et al. Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: psychometric analysis in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(1):86–97.

DeSouza F, et al. Coping with racism: a Perspective of COVID-19 Church Closures on the Mental Health of African Americans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(1):7–11.

Williams DR, et al. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998-2017) Mplus user’s guide. 8th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67.

Seaman SR, Bartlett JW, White IR. Multiple imputation of missing covariates with non-linear effects and interactions: an evaluation of statistical methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-46.

Cacciatore MA, et al. Opposing ends of the spectrum: exploring trust in scientific and religious authorities. Public Underst Sci. 2018;27(1):11–28.

Olagoke AA, Olagoke OO, Hughes AM. Intention to vaccinate against the novel 2019 coronavirus disease: the role of health locus of control and religiosity. J Relig Health. 2021;60(1):65–80.

Plante TG. The Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: assessing faith engagement in a brief and nondenominational manner. Religions. 2010;1(1):3–8.

Sherman AC, Simonton S, Adams DC, Latif U, Plante TG, Burns SK, Poling T. Measuring religious faith in cancer patients: reliability and construct validity of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith questionnaire. Psycho-oncology. 2001;10(5):436–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.523.

Derose KP, Williams MV, Branch CA, Flórez KR, Hawes-Dawson J, Mata MA, Oden CW, Wong EC. A community-partnered approach to developing church-based interventions to reduce health disparities among African-Americans and Latinos. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(2):254–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0520-z.

Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, et al. Body and Soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):97–105.

Burchenal C, Tucker S, Soroka O, Antoine F, Ramos R, Anderson H, Tettey NS, Phillips E. Developing faith-based health promotion programs that target cardiovascular disease and cancer risk factors. J Relig Health. 2022;61(2):1318–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01469-2.

McNeill LH, Reitzel LR, Escoto KH, Roberson CL, Nguyen N, Vidrine JI, Strong LL, Wetter DW. Engaging Black churches to address cancer health disparities: project CHURCH. Front Public Health. 2018;19(6):191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00191.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016.

Greer TM, Brondolo E, Brown P. Systemic racism moderates effects of provider racial biases on adherence to hypertension treatment for African Americans. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):35–42.

Bazargan M, Cobb S, Assari S. Discrimination and medical mistrust in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of California Adults. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2632.

Idan E, Xing A, Ivory J, Alsan M. Sociodemographic correlates of medical mistrust among African American men living in the East Bay. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(1):115–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2020.0012.

Public Religion Research Institute. PRRI 2022 Census of American religion: religious affiliation updates and trends. 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023; Available from: https://www.prri.org/spotlight/prri-2022-american-values-atlas-religious-affiliation-updates-and-trends/#:~:text=Nearly%20four%20in%20ten%20Americans,%2C%20when%2031%25%20were%20unaffiliated.

Arrington-Sanders R, Hailey-Fair K, Wirtz AL, Morgan A, Brooks D, Castillo M, Trexler C, Kwait J, Dowshen N, Galai N, Beyrer C, Celentano D. Role of structural marginalization, HIV stigma, and mistrust on HIV prevention and treatment among young Black Latinx men who have sex with men and transgender women: perspectives from youth service providers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2019.0165.

Calvert CM, Brady SS, Jones-Webb R. Perceptions of violent encounters between police and young Black men across stakeholder groups. J Urban Health. 2020;97(2):279–95.

Funding

Research reported in this RADx® Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21MH122010-01S1. Data from this study is available to access via the NIH Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Data Hub (RADx Data Hub).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jacquelyn Jacobs: conceptualization, methodology, interpretation, writing—original draft, review; Jennifer Walsh: formal analysis, writing—original draft; critical review; Jesus Valencia: writing—original draft, critical review; Wayne DiFranceisco: formal analysis; Jana Hirschtick: critical review; Bijou Hunt: critical review; Katherine Quinn: critical review, funding acquisition, supervisor; Maureen Benjamins: critical review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Participants consented to their data being published in aggregate.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacobs, J., Walsh, J.L., Valencia, J. et al. Associations Between Religiosity and Medical Mistrust: An Age-Stratified Analysis of Survey Data from Black Adults in Chicago. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01979-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01979-1