Abstract

Background

There is an important gap in the literature concerning the level, inequality, and evolution of financial protection for indigenous (IH) and non-indigenous (NIH) households in low- and middle-income countries. This paper offers an assessment of the level, socioeconomic inequality and middle-term trends of catastrophic (CHE), impoverishing (IHE), and excessive (EHE) health expenditures in Mexican IHs and NIHs during the period 2008–2020.

Methods

We conducted a pooled cross-sectional analysis using the last seven waves of the National Household Income and Expenditure Survey (n = 315,829 households). We assessed socioeconomic inequality in CHE, IHE, and EHE by estimating their Wagstaff concentration indices according to indigenous status. We adjusted the CHE, IHE, and EHE by estimating a maximum-likelihood two-stage probit model with robust standard errors.

Results

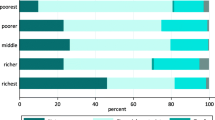

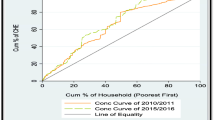

We observed that, during the period analyzed, CHE, IHE, and EHE were concentrated in the poorest IHs. CHE decreased from 5.4% vs. 4.7% in 2008 to 3.4% vs. 2.9% in 2014 in IHs and NIHs, respectively, and converged at 2008 levels towards 2020. IHE remained unchanged from 2008 to 2014 (1.6% for IHs vs. 1.0% for NIHs) and increased by 40% in IHs and NIHs during 2016–2020. EHE plunged in 2014 (4.6% in IHs vs. 3.8% in NIHs), then rose, and remained unchanged during 2016–2020 (6.7% in IHs and 5.6% in NIHs).

Conclusion

In pursuit of universal health coverage, health authorities should formulate and implement effective financial protection mechanisms to address structural inequalities, especially forms of discrimination including racialization, that vulnerable social groups such as indigenous peoples have systematically faced. Doing so would contribute to closing the persistent ethnic gaps in health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author on request.

References

Wagstaff A, Eozenou P, Smitz M. Out-of-pocket expenditures on health: a global stocktake. World Bank Res Obs. 2020;35:123–57.

World Health Organization (WHO). The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva PP - Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Ruano AL, Rodríguez D, Rossi PG, Maceira D. Understanding inequities in health and health systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: a thematic series. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:94.

Costa JC, Mujica OJ, Gatica-Domínguez G, del Pino S, Carvajal L, Sanhueza A, et al. Inequalities in the health, nutrition, and wellbeing of Afrodescendant women and children: a cross-sectional analysis of ten Latin American and Caribbean countries. Lancet Reg Heal – Am. 2022;15:1–17.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de los pueblos indígenas [Internet]. Comunicado de prensa N° 4300/22. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: INEGI; 2022. 1–7. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2022/EAP_PueblosInd22.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2023.

Gall O. Mestizaje y racismo en México. Nueva Soc [Internet]. 2021; Marzo-Abri:1–16. https://nuso.org/articulo/mestizaje-y-racismo-en-mexico/. Accessed 10 Jul 2023.

Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. J Popul Res [Internet]. 2016;33:83–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-016-9159-y.

Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (INPI). Población indígena en hogares según pueblo indígena por entidad federativa, 2020 [Internet]. Población autoadscrita indígena y afromexicana e indígena en hogares con base en el Censo Población y Vivienda 2020. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: INEGI 2022. 1-6. https://www.inpi.gob.mx/indicadores2020/. Accessed 5 Mar 2023.

Vejo TP. Raza y construcción nacional. México, 1810-1910. In: Artigas B, editor. Raza y política en Hisp. 1st ed. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: El Colegio De Mexico; 2018. p. 61–100.

Fábregas Puig AA. Historia mínima del indigenismo en América Latina. 1st ed. El Colegio De Mexico; 2021.

Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Meneses-Navarro S, Reyes-Morales H, Rivera-Dommarco JÁ. The health of indigenous peoples: challenges and perspectives. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62:235–6.

Becerril-Montekio V, Meneses-Navarro S, Pelcastre-Villafuerte B, Serván-Mori E. The Unarticulated Mexican Public Health System: Why is it useful to distinguish between fragmentation and segmentation? article submitted to the J Public Heal. Policy. 2023, currently under review.

McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, Meheus F, Thiede M, Akazili J, et al. Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:871–6.

Vieira Machado C, Dias de Lima L. Health policies and systems in Latin America: regional identity and national singularities. Cad Saude Publica. 2017;33Suppl 2:e00068617.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global spending on health: weathering the storm. Geneva 27, Switzerland; 2020.

Knaul FM, Arreola-Ornelas H, Méndez-Carniado O. Financial protection in health: updates for Mexico to 2014. Salud Publica Mex. 2016;58:341–50.

Serván-Mori E, Gómez-Dantés O, Contreras-Loya D, Flamand L, Cerecero-García D, Arreola-Ornelas H, et al. Increase of catastrophic and impoverishing health expenditures in Mexico associated to policy changes and the COVID-19 pandemic. article submitted to the J Glob Heal. 2023, accepted and in process.

Micah AE, Cogswell IE, Cunningham B, Ezoe S, Harle AC, Maddison ER, et al. Tracking development assistance for health and for COVID-19: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 204 countries and territories, 1990-2050. Lancet. 2021;398:1317–43.

INEGI, editor. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Panorama sociodemográfico de México. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020 [Internet]. 1st ed. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: INEGi; 2021. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825197711. Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

González Block MÁ, Reyes Morales H, Hurtado LC, Balandrán A, Méndez E. Mexico: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2020;22:1–222.

Meneses Navarro S, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Becerril-Montekio V, Serván-Mori E. Overcoming the health systems' segmentation to achieve universal health coverage in Mexico. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2022;37(6):3357–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3538.

Frenk J, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, Lezana MA, Knaul FM. Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico. Lancet. 2006;368:1524–34.

Secretaría de Gobernación (SEGOB). Decreto por el que se reforman, adicionan y derogan diversas disposiciones de la Ley General de Salud y de la Ley de los Institutos Nacionales de Salud [Internet]. Ciudad de México, México, México: Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF); 2019 p. 1–17. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5580430&fecha=29/11/2019#gsc.tab=0. Accessed 15 Jul 2023.

Gilardino RE, Valanzasca P, Rifkin SB. Has Latin America achieved universal health coverage yet? Lessons from four countries. Arch Public Heal. 2022;80:38.

Reich MR. Restructuring health reform. Mexican style. Heal Syst Reform. 2020;6:e1763114.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares 2020 (ENIGH). Nueva serie: Diseño muestral [Internet]. Ciudad de México, México; 2021. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463901228. Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

Serván-Mori E, Orozco-Núñez E, Guerrero-López CM, Miranda JJ, Jan S, Downey L, et al. A gender-based and quasi-experimental study of the catastrophic and impoverishing health-care expenditures in Mexican households with elderly members, 2000-2020. Heal Syst Reform. 2023;9:1–15.

United Nations (UN). Department of Economic and Social Affairs-Statistics Division. Classification of individual consumption according to purpose (COICOP) 2018. New York; 2018. Report No.: 99

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7.

Essue BM, Laba T-L, Knaul F, Chu A, Van MH, Nguyen P, Jan TK, S. Economic burden of chronic ill health and injuries for households in low- and middle-income countries. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, Mock CN, et al., editors. Dis Control priorities Improv Heal reducing poverty [Internet]. 3rd ed. Washington DC 20433, USA: The World Bank; 2017. p. 121–43. Available from: https://dcp-3.org/sites/default/files/chapters/DCP3%20Volume%209_Ch%206.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022.

Serván-Mori, E., Juárez-Ramírez, C., Meneses-Navarro, S. et al. Ethnic Disparities in Effective Coverage of Maternal Healthcare in Mexico, 2006–2018: a Decomposition Analysis. Sex Res Soc Policy 20, 561–574 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00685-5.

Corntassel J. Who is indigenous? ‘Peoplehood’ and ethnonationalist approaches to rearticulating indigenous identity. Natl Ethn Polit. 2003;9:75–100.

Haughton J, Khandker SR. Handbook on poverty and inequality. 1st ed. Washington DC, USA: World Bank; 2009.

Poirier MJP, Grépin KA, Grignon M. Approaches and alternatives to the wealth index to measure socioeconomic status using survey data: a critical interpretive synthesis. Soc Indic Res. 2020;148:1–46.

Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO). Índice de marginación por entidad federativa y municipio 2020. Nota técnico-metodológica [Internet]. Ciudad de México, México. 2021; https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/685354/Nota_te_cnica_IMEyM_2020.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2022.

Wagstaff A. The concentration index of a binary outcome revisited. Health Econ. 2011;20:1155–60.

O’Donnell O, O’Neill S, Van Ourti T, Walsh B. conindex: estimation of concentration indices. Stata J. 2016;16:112–38.

Van de Ven WPMM, Van Praag BMS. The demand for deductibles in private health insurance: a probit model with sample selection. J Econom. 1981;17:229–52.

Menéndez E. Salud intercultural: Propuestas, acciónes y fracasos. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;2:109–18.

Meneses-Navarro, S., Serván-Mori, E., Heredia-Pi, I. et al. Ethnic disparities in sexual and reproductive health in Mexico After 25 Years of Social Policies. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2022;19:975–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00692-0.

Tanous O, Asi Y, Hammoudeh W, Mills D, Wispelwey B. Structural racism and the health of Palestinian citizens of Israel. Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2023;18:2214608. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2023.2214608.

Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial spproach. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2012;102:936–44. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544.

Castro Pérez R, Villanueva LM. El campo médico en México. Hacia un análisis de sus subcampos y sus luchas desde el estructuralismo genético de Bourdieu. Sociológica. 2019;34:73–113.

Menéndez E. Modelo hegemónico, modelo alternativo subordinado, modelo de autoatención. Caracteres estructurales. La Antropol médica en México. 1992;1:97–111.

Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Meneses-Navarro S, Sánchez-Domínguez M, Meléndez-Navarro D, Freyermuth-Enciso G. Condiciones de salud y uso de servicios en pueblos indígenas de México. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62:810–9.

Alfonso YN, Bishai D, Bua J, Mutebi A, Mayora C, Ekirapa-Kiracho E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a voucher scheme combined with obstetrical quality improvements: quasi experimental results from Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:88–99.

Mussa EC, Agegnehu D, Nshakira-Rukundo E. Impact of conditional cash transfers on enrolment in community-based health insurance among female-headed households in south Gondar zone, Amhara region. Ethiopia. SSM - Popul Heal. 2022;17:1–10.

Feldman BS, Zaslavsky AM, Ezzati M, Peterson KE, Mitchell M. Contraceptive use, birth spacing, and autonomy: an analysis of the Oportunidades program in rural Mexico. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40:51–62.

Banerjee AV, Duflo E, Glennerster R, Kothari D. Improving immunisation coverage in rural India: clustered randomised controlled evaluation of immunisation campaigns with and without incentives. Brithis Med J. 2010;340:1291.

Wang P, Connor AL, Guo E, Nambao M, Chanda-Kapata P, Lambo N, et al. Measuring the impact of non-monetary incentives on facility delivery in rural Zambia: a clustered randomised controlled trial. Trop Med Int Heal. 2016;21:515–24.

Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:1–44.

Hirai M, Morris J, Luoto J, Ouda R, Atieno N, Quick R. The impact of supply-side and demand-side interventions on use of antenatal and maternal services in western Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:453.

Serván-Mori E, Cerecero-García D, Heredia-Pi I, Pineda-Antúnez C, Sosa-Rubí S, Nigenda G. Improving the effective maternal-child health care coverage through synergies between supply and demand-side interventions: evidence from Mexico. J Glob Health. 2019;9:1–12.

Gopalan SS, Varatharajan D. Addressing maternal healthcare through demand side financial incentives: experience of Janani Suraksha Yojana program in India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:319.

Bowser D, Gupta J, Nandakumar A. The effect of demand- and supply-side health financing on infant, child, and maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries. Heal Syst Reform. 2016;2:147–59.

Masino S, Niño-Zarazúa M. Improving financial inclusion through the delivery of cash transfer programmes: the case of Mexico’s Progresa-Oportunidades-Prospera Programme. J Dev Stud. 2020;56:151–68.

Romero-Martínez M, Shamah-Levy T, Vielma-Orozco E, Heredia-Hernández O, Mojica-Cuevas J, Cuevas-Nasu L, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: Metodología y perspectivas. Salud Publica Mex. 2019;61:917–23.

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL). Nota técnica sobre la carencia por acceso a los servicios de salud, 2018-2020 [Internet]. Ciudad de México, México; 2021. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Documents/MMP_2018_2020/Notas_pobreza_2020/Nota_tecnica_sobre_la_carencia_por_acceso_a_los_servicios_de_salud_2018_2020.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2021.

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL). El Sistema de protección social en Salud: Resultados y diagnóstico de cierre [Internet]. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: CONEVAL; 2020;1–93. https://www.coneval.org.mx/evaluacion/iepsm/documents/analisis_spss_2020.pdf. Accessed 09 Apr 2020.

Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Revised Edition. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Meneses Navarro S, González Block MÁ, Quezada Sánchez AD, Freyermuth EG. Evolución de la equidad en el acceso a servicios hospitalarios según composición indígena municipal en Chiapas, México: 2001 a 2009. In: Page Pliego JT, editor. Enfermedades del rezago y emergentes desde las ciencias Soc y la salud pública. 1st ed. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 2014. p. 17–36.

Meneses-Navarro S, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Bautista-Ruiz ÓA, Toledo-Cruz RJ, De la Rosa-Cruz SA, Alcalde-Rabanal J, et al. Innovación pedagógica para mejorar la calidad del trato en la atención de la salud de mujeres indígenas. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;63:51–9.

Salas-Ortiz A. Socioeconomic inequalities and ethnic discrimination in COVID-19 Outcomes: the case of Mexico. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01571-z.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable assistance of Patricia E. Solís and Michael H. Sumner in translating this manuscript into English.

Data Sharing

The data for the analysis were requested and obtained from the surveys public repository hosted at the National Institute for Statistics and Geography (available at https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enigh/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required by our institution for this type of study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

We dedicate this manuscript to our colleague, professor, and friend, Sandra Sosa-Rubí, PhD, who passed away in March 2021; Sandra consistently inspired us in our analysis of equity and financial protection in health during her fruitful lifetime.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Serván-Mori, E., Meneses-Navarro, S., Garcia-Diaz, R. et al. Inequitable Financial Protection in Health for Indigenous Populations: the Mexican Case. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01770-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01770-8