Abstract

Background

Understanding similarities and differences between groups with intersecting social identities provides key information in research and practice to promote well-being. Building on the intersectionality literature indicating significant gender and racial/ethnic differences in depressive symptoms, the present study used quantile regression to systematically present the diversity in the development of depressive symptoms for individuals with intersecting gender, race/ethnicity, and levels of symptoms.

Methods

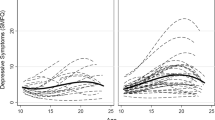

Information from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79: Child and Young Adult study was employed. A detailed picture of depressive symptom trajectories from low to high quantiles was illustrated by depicting 13 quantile-specific trajectories using follow-up data from ages 15 to 40 in six gender-race/ethnicity groups: both genders of Black, Hispanic, and non-Black, non-Hispanic individuals.

Results

From low to high quantiles, Black and non-Black, non-Hispanic individuals showed mostly curved, and Hispanic individuals showed mostly flat trajectories. Across the six gender-race/ethnicity groups, the trajectories below 0.50 quantiles were similar in levels and shapes from mid-adolescence to young adulthood. The differences between the six gender-race/ethnicity groups widened, indicated by outspreading trajectories, especially at quantiles above 0.50. Furthermore, non-Black, non-Hispanic males and females showed especially fast-increasing patterns at quantiles above 0.75. Among those without or with only a high school degree, Black females and non-Black, non-Hispanic females tended to report similar levels of depressive symptoms higher than other groups at high quantiles. These unique longitudinal trajectory profiles cannot be captured by the mean trajectories.

Conclusions

The intersectionality of gender, race/ethnicity, and quantile of symptoms on the development of depressive symptoms was identified. Further studying the mechanism explaining this diversity can help reduce mental health disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The raw data required to reproduce the above findings are publicly available to download from https://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy79-children.htm.

Code Availability

Not applicable

References

Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):72–9.

López-López JA, Kwong ASF, Washbrook E, Pearson RM, Tilling K, Fazel MS, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and adult educational and employment outcomes. BJPsych Open. 2019;6(1):e6-e.

Kwong ASF, Manley D, Timpson NJ, Pearson RM, Heron J, Sallis H, et al. Identifying critical points of trajectories of depressive symptoms from childhood to young adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(4):815–27.

Hargrove TW, Halpern CT, Gaydosh L, Hussey JM, Whitsel EA, Dole N, et al. Race/ethnicity, gender, and trajectories of depressive symptoms across early- and mid-life among the Add Health cohort. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 2020;7(4):619–29.

Brown JS, Meadows SO, Elder GH Jr. Race-ethnic inequality and psychological distress: depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(6):1295–311.

Shore L, Toumbourou JW, Lewis AJ, Kremer P. Review: Longitudinal trajectories of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and their predictors – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Mental Health. 2018;23(2):107–20.

Musliner KL, Munk-Olsen T, Eaton WW, Zandi PP. Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: patterns, predictors and outcomes. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;192:199–211.

Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster J-Y, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health (Lond). 2019;15:1745506519844044.

Barker ED, Copeland W, Maughan B, Jaffee SR, Uher R. Relative impact of maternal depression and associated risk factors on offspring psychopathology. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2018;200(2):124–9.

Minh A, Bültmann U, Reijneveld SA, van Zon SKR, McLeod CB. Childhood socioeconomic status and depressive symptom trajectories in the transition to adulthood in the United States and Canada. J. Adolesc. Health. 2021;68(1):161–8.

Yu S. Uncovering the hidden impacts of inequality on mental health: a global study. Transl. Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):98.

Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Abdalla SM, Galea S. Do assets explain the relation between race/ethnicity and probable depression in U.S. adults? PLOS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0239618.

Quesnel-Vallée A, Taylor M. Socioeconomic pathways to depressive symptoms in adulthood: evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(5):734–43.

ten Kate J, de Koster W, van der Waal J. Why are depressive symptoms more prevalent among the less educated? The relevance of low cultural capital and cultural entitlement. Sociol. Spectr. 2017;37(2):63–76.

Assari S. Combined effects of ethnicity and education on burden of depressive symptoms over 24 Years in middle-aged and older adults in the United States. Brain Sci. 2020;10(4):209.

Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, Cheng Y-P. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Am. Psychol. 2018;73(7):855–83.

Hardcastle K, Bellis MA, Ford K, Hughes K, Garner J, Ramos RG. Measuring the relationships between adverse childhood experiences and educational and employment success in England and Wales: findings from a retrospective study. Public Health. 2018;165:106–16.

López-López JA, Kwong ASF, Washbrook L, Tilling K, Fazel MS, Pearson RM. Depressive symptoms and academic achievement in UK adolescents: a cross-lagged analysis with genetic covariates. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;284:104–13.

Peplinski B, McClelland R, Szklo M. Associations between socioeconomic status markers and depressive symptoms by race and gender: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Ann. Epidemiol. 2018;28(8):535–42.e1.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Association between stressful life events and depression; intersection of race and gender. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 2016;3:349–56.

Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum; 1989.

Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009;64(3):170–80.

Rosenfield S. Triple jeopardy? Mental health at the intersection of gender, race, and class. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(11):1791–801.

Covarrubias A. Quantitative intersectionality: a critical race analysis of the chicana/o educational pipeline. J. Latinos Educ. 2011;10(2):86–105.

King TL, Shields M, Shakespeare T, Milner A, Kavanagh A. An intersectional approach to understandings of mental health inequalities among men with disability. SSM – Popul. Health. 2019;9:100464.

Evans CR, Erickson N. Intersectionality and depression in adolescence and early adulthood: a MAIHDA analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health, 1995–2008. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;220:1–11.

Seng JS, Lopez WD, Sperlich M, Hamama L, Reed Meldrum CD. Marginalized identities, discrimination burden, and mental health: empirical exploration of an interpersonal-level approach to modeling intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;75(12):2437–45.

Roxburgh S. Untangling inequalities: gender, race, and socioeconomic differences in depression. Sociol. Forum. 2009;24(2):357–81.

Patil PA, Porche MV, Shippen NA, Dallenbach NT, Fortuna LR. Which girls, which boys? The intersectional risk for depression by race and ethnicity, and gender in the U.S. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018;66:51–68.

Merlo J. Multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) within an intersectional framework. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;203:74–80.

Green MA, Evans CR, Subramanian SV. Can intersectionality theory enrich population health research? Soc. Sci. Med. 2017;178:214–6.

Evans CR, Williams DR, Onnela J-P, Subramanian SV. A multilevel approach to modeling health inequalities at the intersection of multiple social identities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;203:64–73.

Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986;22(6):723–42.

Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartmann T. A Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST): a self-organization perspective in context. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997;9(4):817–33.

Scott JC, Pinderhughes EE, Johnson SK. How does racial context matter?: Family preparation-for-bias messages and racial coping reported by Black youth. Child Dev. 2020;91(5):1471–90.

Bronwyn Nichols L, Hall J, Margaret BS. Vulnerability and resiliency implications of human capital and linked inequality presence denial perspectives: acknowledging Zigler’s contributions to child well-being. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021;33(2):684–99.

López BG, Luque A, Piña-Watson B. Context, intersectionality, and resilience: moving toward a more holistic study of bilingualism in cognitive science. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2021:No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified.

Adams LM, Miller AB. Mechanisms of mental-health disparities among minoritized groups: how well are the top journals in clinical psychology representing this work? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2022;10(3):387–416.

McCall L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005;30(3):1771–800.

Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;110:10–7.

Bauer GR, Scheim AI. Methods for analytic intercategorical intersectionality in quantitative research: discrimination as a mediator of health inequalities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;226:236–45.

Petscher Y, Logan JAR. Quantile regression in the study of developmental sciences. Child Dev. 2014;85(3):861–81.

Wenz SE. What quantile regression does and doesn’t do: a commentary on Petscher and Logan (2014). Child Dev. 2019;90(4):1442–52.

Konstantopoulos S, Li W, Miller S, van der Ploeg A. Using quantile regression to estimate intervention effects beyond the mean. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019;79(5):883–910.

Hao L, Naiman DQ. Quantile regression. London: SAGE; 2007.

Beyerlein A. Quantile regression—opportunities and challenges from a user’s perspective. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):330–1.

Asim M. Average vs. distributional effects: evidence from an experiment in Rwanda. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2020;79:102274.

Bitler M, Domina T, Penner E, Hoynes H. Distributional analysis in educational evaluation: a case study from the New York City voucher program. J. Res. Educ. Effect. 2015;8(3):419–50.

Law J, Rush R, King T, Westrupp E, Reilly S. Early home activities and oral language skills in middle childhood: a quantile analysis. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):295–309.

Bind M-A, Peters A, Koutrakis P, Coull B, Vokonas P, Schwartz J. Quantile regression analysis of the distributional effects of air pollution on blood pressure, heart rate variability, blood lipids, and biomarkers of inflammation in elderly American men: the normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016;124(8):1189–98.

Contoyannis P, Li J. The dynamics of adolescent depression: an instrumental variable quantile regression with fixed effects approach. J. R. Stat. Soc. A. Stat. Soc. 2017;180(3):907–22.

Koenker R. Quantile regression: 40 years on. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2017;9(1):155–76.

Koenker R. Quantile regression for longitudinal data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2004;91(1):74–89.

Center for Human Resource Research. NLSY79 Child & Young Adult data users guide. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University; 2009.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. NLSY79 Child and Young Adult Data Overview U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2021 [updated April 23. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy79-children.htm#other-documentation.

Koenker R, Portnoy S, Ng PT, Melly B, Zeileis A, Grosjean P, et al. Package ‘quantreg’. Reference manual available at R-CRAN: https://cranrprojectorg/web/packages/quantreg/quantregpdf2021.

Machado JAF, Silva JMCS. Quantiles for counts. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2005;100(472):1226–37.

Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22.

Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, Garcia A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140(4):921–48.

Pascoe EA, Smart RL. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:531–54.

Lee DL, Ahn S. Discrimination against Latina/os: a meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes. Couns. Psychol. 2012;40(1):28–65.

Arizaga JA, Polo AJ, Martinez-Torteya C. Heterogeneous trajectories of depression symptoms in Latino youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020;49(1):94–105.

Kwong ASF, López-López JA, Hammerton G, Manley D, Timpson NJ, Leckie G, et al. Genetic and environmental risk factors associated with trajectories of depression symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2(6):e196587-e.

Thomas JE, Pasch KE, Marti CN, Hinds JT, Wilkinson AV, Loukas A. Trajectories of depressive symptoms among young adults in Texas 2014–2018: a multilevel growth curve analysis using an intersectional lens. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022;57(4):749–60.

Staiger T, Stiawa M, Mueller-Stierlin AS, Kilian R, Beschoner P, Gündel H, et al. Masculinity and help-seeking among men with depression: a qualitative study. Front Psych. 2020;11:599039.

Townsend L, Musci R, Stuart E, Heley K, Beaudry MB, Schweizer B, et al. Gender differences in depression literacy and stigma after a randomized controlled evaluation of a universal depression education program. J. Adolesc. Health. 2019;64(4):472–7.

Cole BP, Ingram PB. Where do I turn for help? Gender role conflict, self-stigma, and college men’s help-seeking for depression. Psychol. Men Masculinities. 2020;21(3):441–52.

Pamplin JR, Bates LM. Evaluating hypothesized explanations for the Black-White depression paradox: a critical review of the extant evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021;281:114085.

Barnes DM, Bates LM. Do racial patterns in psychological distress shed light on the Black–White depression paradox? A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017;52(8):913–28.

Erving CL, Thomas CS, Frazier C. Is the Black-White mental health paradox consistent across gender and psychiatric disorders? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018;188(2):314–22.

Feiss R, Dolinger SB, Merritt M, Reiche E, Martin K, Yanes JA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based stress, anxiety, and depression prevention programs for adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(9):1668–85.

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017;51:30–47.

Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005;34(1):215–20.

Kim G, DeCoster J, Huang C-H, Chiriboga DA. Race/ethnicity and the factor structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: a meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2011;17(4):381–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Eva Yi-Ju Chen and Eli Yi-Liang Tung. Methodology: Eli Yi-Liang Tung. Formal analysis and investigation: Eva Yi-Ju Chen and Eli Yi-Liang Tung. Writing—original draft preparation: Eva Yi-Ju Chen. Writing—review and editing: Eva Yi-Ju Chen and Eli Yi-Liang Tung. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, E.YJ., Tung, E.YL. Similarities and Differences in the Longitudinal Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms from Mid-Adolescence to Young Adulthood: the Intersectionality of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Levels of Depressive Symptoms. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01630-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01630-5