Abstract

Background

Studies have reported positive outcomes of blended care therapy (BCT), which combines face-to-face care with internet modules. However, there is insufficient evidence of its effectiveness across racial and ethnic groups. This study evaluated outcomes of a BCT program, which combined video psychotherapy with internet cognitive-behavioral modules, across race and ethnicity.

Methods

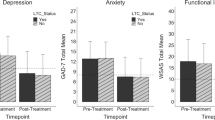

Participants were 6492 adults, with elevated anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] ≥ 8) and/or depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] ≥ 10) symptoms, enrolled in employer-offered BCT. Changes in anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) symptoms during treatment were evaluated using individual growth curve models. Interaction terms of time with race and ethnicity tested for between-group differences. Treatment satisfaction was assessed using a Net Promoter measure (range = 1 (lowest satisfaction) to 5 (greatest satisfaction)).

Results

Participants’ self-reported race and ethnicity included Asian or Pacific Islander (27.5%), Black or African American (5.4%), Hispanic or Latino (9.3%), and White (47.2%). Anxiety symptoms decreased during treatment (p < 0.01), with greater reductions among Hispanic or Latino participants compared to White participants (p < 0.05). Depressive symptoms decreased across treatment (p < 0.01), with significantly greater decreases among some racial and ethnic groups compared to White participants. Declines in anxiety and depressive symptoms slowed across treatment (p’s < 0.01), with statistically significant differences in slowing rates of depressive symptoms across some racial and ethnic groups. Among participants with responses (28.45%), average treatment satisfaction ranged from 4.46 (SD = 0.73) to 4.67 (SD = 0.68) across race and ethnicity (p = 0.001). Racial and ethnic differences in outcomes were small in magnitude.

Conclusions

BCT for anxiety and depression can be effective across diverse racial and ethnic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are common mental disorders in the USA and worldwide [1]. Efficacious psychotherapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) exist to treat these conditions [2, 3]; however, many adults with depression and anxiety do not receive mental health care [4, 5]. This disproportionately impacts several communities of color who access care at lower rates compared to White adults [4, 6]. In the USA, the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms increased threefold during the COVID-19 pandemic relative to before the pandemic [7,8,9], with some communities of color experiencing a greater burden than White adults [9, 10]. Now, more than ever, effective and accessible mental health services are essential to address mental health care needs across diverse populations.

Because of their greater scalability, telehealth, and internet-based psychological interventions have the potential to mitigate accessibility barriers to traditional psychotherapy [11, 12] and provide more accessible care to communities of color that experience mental health disparities [13, 14]. It is essential such programs demonstrate effectiveness and equitable outcomes across racial and ethnic groups when delivered at a meaningful scale. Yet, outcomes research of internet-based mental health interventions has primarily been conducted in samples that under-represent communities of color [14], and racial and ethnic differences in clinical outcomes of these interventions are not commonly evaluated. Studies of tele-counseling interventions and internet CBT (iCBT) have reported positive anxiety and depression treatment outcomes among communities of color [15,16,17]. However, most of this research has been limited by small sample sizes or has evaluated programs targeting specific racial and ethnic groups, increasing the difficulty in fully grasping the impact of large-scale interventions that aim to successfully treat diverse populations.

These research gaps also extend to blended care therapy (BCT), another more scalable treatment for anxiety and depression. BCT combines face-to-face psychotherapy sessions with digital content (e.g., lessons and exercises to be completed between therapy sessions) and has numerous potential benefits including reducing treatment dropout and improving psychotherapy outcomes [18]. Whereas, a recent review of over 40 studies supports the effectiveness of blended care interventions compared to controls not receiving treatment [18], BCT outcomes across racial and ethnic groups are not well understood. The lack of clarity around whether telehealth and internet-based psychological interventions are more effective for some racial and ethnic groups over others reinforces the need to evaluate the outcomes of such interventions across race and ethnicity [14].

In order to provide equitable mental health care across diverse populations, researchers have highlighted the need for incorporating cultural competency within both the organization and the direct services of mental health care providers [19, 20]. Such an approach aims to ensure that mental health providers and the care they offer are responsive to the unique cultural attributes of the communities served. This includes the availability of mental health services that address the care needs of the target community [19, 20]. These recommendations should be extended to internet-based psychological care, including telehealth, that aims to widen the reach of traditional psychotherapy and serves broader populations which include marginalized groups (e.g., communities of color). Telehealth, in particular, could facilitate access to culturally competent care which may have limited reach otherwise [21]. Culturally competent care can be further built upon by also incorporating culturally responsive approaches such as cultural humility into care delivery [22]. Unlike cultural competency which can suggest providers can reach competence in their ability to provide care within participants’ unique cultural contexts, culturally responsive care highlights that providing such treatment requires ongoing self-reflection and learning on the part of providers [23]. There is a shortage of large-scale telehealth and internet-based psychological interventions that are delivered with an emphasis on cultural competence or responsiveness, despite suggestions that incorporating cultural factors into such interventions could improve engagement and outcomes [14].

In order to address the described research gaps and generate further evidence of digital mental health care delivered with cultural responsiveness, the current study evaluated outcomes of a large-scale, employer-offered, culturally responsive blended care therapy (BCT) program, which combined live video-based psychotherapy sessions with therapist-assigned iCBT modules, across racial and ethnic groups. Specifically, this study assessed clinical outcomes (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety) across treatment, as well as end-of-care treatment satisfaction, in a large, multi-ethnic sample that included a significant proportion of participants from communities of color. This research expands upon a prior large-scale study of this BCT program that evaluated clinical outcomes without investigating potential racial and ethnic differences [24]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in the USA to evaluate outcomes of a large-scale BCT program across diverse racial and ethnic groups.

Methods

Design and Participants

This was a follow-up study of a pragmatic retrospective cohort analysis that included participants who received care between September 3rd, 2019 and July 21st, 2021 [24]. The BCT program evaluated in the current study was a mental health benefit offered by Lyra Health and its contracted partner, Lyra Clinical Associates, to employees, and their dependents, through their employer. Participants were employed by, or dependents of employees from, 77 companies covering a diverse array of industry sectors. All participants and therapists resided in the USA across all 4 regions (i.e., Northeast, Midwest, South, West) [25]. Adults aged ≥ 18 years who began the BCT program during the study period with elevated symptoms of anxiety (i.e., Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] score ≥ 8) [26] and/or depression (i.e., Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] score ≥ 10) [27] upon registration, were eligible for the current study (N = 7,331). In order to minimize any potential influence of treatment on baseline assessment scores, participants were excluded if they did not have a valid baseline assessment that was collected within 2 weeks of the first therapy session and before the second therapy session. Because this study aimed to evaluate outcomes over the course of treatment and at the end of care, participants were also excluded if they did not have at least 1 valid follow-up assessment that was completed within 5 weeks of their final therapy session and within 15.6 weeks of the first therapy session (i.e., within 1 standard deviation of the average BCT program duration). Participants who did not self-report gender were also excluded. Finally, participants who opted not to disclose race and ethnicity, or were otherwise missing race and ethnicity data, were excluded. The final sample size was 6492 participants (88.56% of the eligible sample). Figure 1 depicts the participant study flowchart.

Treatment

A previous publication provided a comprehensive description of the BCT program [28]. In sum, the BCT program merges synchronous video-based psychotherapy sessions with asynchronous digital tools that are implemented in-between live therapy sessions. Quality assurance included the use of an internal fidelity rating scale to assess the content of therapy sessions. Participants are recommended 5–10 therapists based on factors such as clinical fit and modality preference and self-select whom they ultimately want to work with. Additionally, as a part of the BCT onboarding process, participants have the option to search for therapists from communities of color who also have expertise in the area in which they are seeking support (e.g., racial stress).

Digital tools were established from transdiagnostic approaches to CBT, including Acceptance Commitment Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy [29, 30]. These tools comprise lessons, exercises, and assessments. Digital lessons use a storytelling approach to follow the personal treatment journey of characters who are experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms.

The BCT program incorporates culturally responsive practices [22, 31, 32], which include providing culturally appropriate support across diverse racial and ethnic identities. From a clinical perspective, culturally responsive care (CRC) grounds evidenced-based practices in the values of cultural responsiveness, humility, and respect. The integration of these values into clinical practice is a skill that can be developed and strengthened over time. Thus, training and education are key components of CRC. As mentioned previously, CRC encompasses ongoing learning; therefore, the BCT program is continuously enhanced to increase its cultural responsiveness. Because it is essential that culturally responsive blended care fuses culturally responsive approaches into both the psychotherapy and digital tools, these approaches are summarized below.

Culturally responsive therapists

BCT providers complete a webinar on core CRC concepts, such as intersectionality and power and privilege within the therapeutic relationship [33, 34]. Additionally, therapists have access to individual and group consultation with specialists in culturally responsive care, and continuing education training that builds upon core culturally responsive care concepts. CRC is also incorporated into measuring the quality of care with the BCT program. For example, therapists’ level of cultural attunement and responsiveness is a component of the vetting process and overall clinical performance. In addition, quality assurance includes regular assessment of therapeutic alliance. The on-going consultation support clinical supervisors offer their providers plays a significant role in client care as it is an opportunity for providers to strengthen their clinical skills. For this reason, clinical supervisors also receive similar training and consultation support in CRC focused primarily on enhancing culturally responsive supervision skills.

Culturally responsive digital tools

Culturally responsive care is also integrated into the development of digital tools available in the platform. For example, BCT includes digital lessons and handouts on coping with and responding to racial microaggressions [35,36,37,38]. Specific digital tools are assigned by therapists to ensure they are aligned with clients’ unique case formulation and presenting concerns for therapy [28]. In addition, all digital content is reviewed with specific attention given to the representation of characters from communities of color in the storylines and to the language used in sharing the experiences of these characters. Content reviews also aim to limit the perpetuation of problematic stereotypes rooted in racial bias.

Study Measures

As a part of BCT, participants’ anxiety and depressive symptom severity were monitored via weekly administration of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales. A PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 indicates clinically elevated depressive symptomatology [27], and GAD-7 scores ≥ 8 indicate clinically elevated anxiety symptomatology [26]. Among those with clinically elevated symptoms at baseline, recovery was defined as a reduction in scores below the clinical threshold of 10 on the PHQ-9 and/or 8 on the GAD-7 by the final assessment. Meanwhile, among these participants, reliable improvement was defined as a reduction of 4 or more on the GAD-7 and/or 6 or more on the PHQ-9 by the final assessment. Reliable improvement score cutoffs were derived from reliable change indices calculated for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales in prior research [39, 40].

Self-reported treatment satisfaction was collected after participants’ final BCT session, using the following Net Promoter measure [41]: “How likely are you to recommend your Lyra therapist to someone with needs similar to yours?”. In this study, responses were coded as: “Extremely unlikely” = 1, “Unlikely” = 2; “Neutral” = 3; “Likely” = 4; “Extremely likely” = 5. This item was averaged, and higher scores indicated greater satisfaction with BCT.

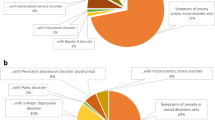

Along with additional demographic data, race and ethnicity were collected from BCT participants for the purpose of evaluating treatment quality and outcomes across demographic groups. Participants self-reported race and ethnicity during the client intake and registration. Participants reported whether they identified as “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “Black or African American,” “Hispanic or Latino,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” “White,” “Prefer Not to Disclose,” and/or “Other.” Participants who selected more than one race or ethnicity (e.g., those who selected both “White” and “Hispanic or Latino”, etc.) were re-categorized as “Multiple.” In addition, those who reported “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” or “Other” were re-categorized as “Other” due to small sample sizes. As mentioned previously, participants who selected “Prefer Not to Disclose” or did not respond to this item were excluded from this study. Self-reported highest educational attainment was re-categorized “College Degree or Higher” (i.e., “College graduate or above”) versus “No College Degree” (i.e., “Some college or AA degree,” “High school graduate/GED or equivalent,” “9-11th grade (Includes 12th grade with no diploma),” “Less than 9th grade”). Participants also rated their financial status (i.e., “Good,” “Fair,” “Poor”), in addition to self-reporting age and gender.

Statistical Analysis

Potential differences in mean satisfaction scores, duration in treatment, and number of psychotherapy sessions across race and ethnicity were tested using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni-corrected follow-up comparisons [42]. In order to assess end-of-care treatment response, rates of reliable improvement, recovery, reliable improvement and recovery, and reliable improvement or recovery in symptoms of anxiety or depression were calculated. Racial and ethnic differences in these outcomes were assessed using χ2 tests. To assess outcomes over the course of care, changes in weekly anxiety and depression symptoms throughout the treatment course were modeled using individual growth curve (IGC) analysis [43]. Participants’ responses to anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) symptom measures were modeled as non-linear IGCs by incorporating linear (Week) and quadratic (Week2) time indicators as fixed effects. Random effects for the intercept term were estimated at the participant and therapist levels, along with random effects for the linear and quadratic effects at the participant level. Potential differences in initial symptom levels across race and ethnicity were evaluated by adding race and ethnicity categories as predictors, with White participants as the reference group. Differences in the magnitude of the initial decline in symptoms were evaluated by incorporating interaction terms between each race and ethnicity predictor and the (linear) Time variable, whereas potential differences in the tapering of initial decline were modeled by including interaction terms between each race and ethnicity predictor and the Time2 variable. Because therapy sessions were the most fundamental component of the BCT program, the final models also incorporated time-varying covariate effects of engaging with a video therapy session during the past week (last 7 days) or prior week (8–14 days). Potential differences in the magnitude of these time-varying covariate coefficients across race and ethnicity categories were also evaluated by incorporating the corresponding interaction terms. For each outcome, models were also fit that included age and gender as fixed effects. Because the addition of these variables did not significantly improve model fit, they were excluded from the final models. However, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 report both the final models and models that include age and gender as fixed effects.

Results

Participant characteristics of the final sample are provided in Table 1 (N = 6492). Most participants were White adults (n = 3065; 47.21%), followed by Asian or Pacific Islander adults (n = 1785; 27.50%). On average, participants were aged 33.19 years (SD = 8.75), and the majority were female (n = 4239; 65.30%). Most participants had attained a college degree or higher (n = 5185; 79.87%), and a large proportion self-reported their financial status as “good” (n = 4,012; 61.80%) or “fair” (n = 2099; 32.33%).

Overall, 89.53% of the sample reported baseline GAD-7 scores above the clinical threshold (≥ 8), and there were no significant differences across racial and ethnic groups (χ2(5) = 3.89, p = 0.57, φ = 0.07). Among participants with a baseline GAD-7 ≥ 8, a one-way ANOVA found significant (albeit small) cross-group differences among mean baseline GAD-7 scores (F (5, 5806) = 2.60, p = 0.02, adjusted R2 = 0.0001). However, post-hoc pairwise independent sample t-tests did not find statistically significant differences between any two racial and ethnic groups after performing Bonferroni corrections. Meanwhile, 58.56% of the sample reported baseline scores within the clinical range on the PHQ-9 (≥ 10), and there were statistically significant differences across racial and ethnic groups (χ2 (5) = 17.36, p = 0.004, φ = 0.03). Among participants with a baseline PHQ-9 ≥ 10, there were also significant cross-group differences in mean PHQ-9 scores at baseline (F (5, 3796) = 3.16, p = 0.008, adjusted R2 = 0.003). However, in post-hoc tests, there was only a statistically significant difference in baseline PHQ-9 scores between Black or African American and White participants after performing Bonferroni corrections (Mean baseline PHQ-9 scores = 14.82 versus 13.94, respectively; p = 0.02).

Treatment Duration

Treatment duration for the overall sample and across race and ethnicity are provided in the top panel of Table 2. On average, participants attended 6.01 therapy sessions (SD = 3.55) and were under care for 7.61 weeks (SD = 6.21). There were significant differences in the number of therapy sessions (F (5, 6486) = 3.76, p = 0.002) across race and ethnicity, but not the duration of care (F (5, 6486) = 1.84, p = 0.10, adjusted R2 < 0.001). The magnitude of the differences in the mean number of therapy sessions across racial and ethnic groups was trivial (adjusted R2 = 0.002). In post-hoc tests, Asian or Pacific Islander adults completed significantly fewer sessions (mean = 5.76, SD = 3.37) than those who reported multiple racial or ethnic groups (mean = 6.28, SD = 3.60) and White adults (mean = 6.12, SD = 3.57) after Bonferroni corrections (p’s = 0.04 and 0.006, respectively).

Treatment Satisfaction

In total, 1847 (28.45%) participants self-reported treatment satisfaction (Table 2). There were no significant differences in the likelihood of responding to the satisfaction question (χ2 (5) = 1.75, p = 0.88, φ = 0.02) across racial and ethnic groups. However, independent samples t-tests suggested that responders reported significantly lower scores on the final GAD-7 (MGAD-7 = 4.13, SDGAD-7 = 3.73) and PHQ-9 (MPHQ-9 = 3.73, SDPHQ-9 = 3.92), relative to those who did not respond (MGAD-7 = 5.96, SDGAD-7 = 4.14; MPHQ-9 = 5.39, SDPHQ-9 = 4.58; both p’s < 0.001). The effect sizes of these differences were large (PHQ-9 & GAD-7 Hedges’ g = 1.46 and 1.76, respectively). Among responders, 92.10% were “extremely likely” or “likely” to recommend their Lyra therapist to someone with similar needs, and the mean score was 4.57 (SD = 0.73). ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences across racial and ethnic groups for satisfaction responses (F (5, 1841) = 4.07, p = 0.001), though these differences were small in magnitude, accounting for < 1% of the total variance in responses (adjusted R2 = 0.008). In post-hoc tests, Asian or Pacific Islander adults had significantly lower scores (mean = 4.46, SD = 0.73) than Hispanic or Latino adults (mean = 4.67, SD = 0.68), those who reported multiple racial or ethnic groups (mean = 4.66, SD = 0.67), and White adults (mean = 4.61, SD = 0.73) after Bonferroni corrections (p’s < 0.02, < 0.03, < 0.003; respectively).

Rates of Reliable Improvement and Recovery

Table 3 provides estimates of reliable improvement and recovery in either anxiety or depression symptoms across race and ethnicity. Across racial and ethnic groups, differences in the prevalence of reliable improvement and recovery χ2 (5) = 16.51, p = 0.01, φ = 0.06, as well as the likelihood of experiencing reliable improvement or recovery χ2 (5) = 11.44, p = 0.04, φ = 0.05 met the threshold for statistical significance, but φ coefficients suggested that the observed cross-group differences were very small. More specifically, across racial and ethnic groups, the prevalence of reliable improvement or recovery in anxiety or depression symptoms ranged from 83.54 to 90.02%. Meanwhile, across racial and ethnic groups, the prevalence of reliable improvement and recovery in anxiety or depression ranged from 66.46 to 76.04%. In post-hoc tests, there were no statistically significant differences in reliable improvement and/or recovery outcomes between any two racial or ethnic groups after Bonferroni corrections.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Trajectories of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Anxiety symptoms

The estimate for the fixed intercept (b = 11.55; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 11.41, 11.69) describes the average initial GAD-7 score for White participants (Table 4). The initial trajectory slope suggests that among White participants, GAD-7 scores decline approximately 1 unit per week (b = − 1.05; 95% CI = − 1.10, − 1.01) during the initial stage of therapy, and a significant Week × Hispanic or Latino interaction (b = − 0.12; 95% CI = − 0.23, − 0.01) indicates that participants with this identity show a stronger (more negative) initial decline in symptoms. The initial trajectories for the remaining racial and ethnic groups did not significantly differ from the reference group. The rate of change in GAD-7 symptoms attenuated over the course of treatment (Week2 b = 0.05; 95% CI = 0.04, 0.05), and the degree of attenuation did not significantly differ across race and ethnicity.

Depressive symptoms

The estimate for the fixed intercept (b = 12.69; 95% CI = 12.50, 12.88) describes the average initial PHQ-9 score for White participants. Statistically significant Week × Asian or Pacific Islander (b = − 0.15; 95% CI = − 0.26, − 0.05), Week × Black or African American (b = − 0.26; 95% CI = − 0.45, − 0.07), and Week × Hispanic or Latino (b = − 0.17; 95% CI = − 0.32, − 0.02) interactions suggest that these participants show a steeper (more negative) initial decline in depression symptoms, relative to White participants (linear b = − 1.19; 95% CI = − 1.25, − 1.12; Table 4). The decline in PHQ-9 becomes less pronounced over the course of treatment among White participants (Week2 b = 0.05; 95% CI = 0.05, 0.06). Moreover, the presence of significant Week2 × Asian or Pacific Islander (b = 0.01; 95% CI = 0.00, 0.02) and Week2 × Black or African American (b = 0.02; 95% CI = 0.00, 0.03) interactions suggest that these participants exhibited a stronger attenuation of their symptom trajectories (relative to White Participants) over the treatment course.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Time-varying Covariate Effects of Session Engagement

Anxiety symptoms

A significant coefficient for the first-order effect of past-week sessions (b = − 0.80; 95% CI = − 0.89, − 0.71) suggests that engaging with a therapy session during the previous week was associated with lower GAD-7 scores among White participants (Table 4). In addition, significant interactions emerged for Black or African American (b = − 0.47; 95% CI = − 0.77, − 0.18) and Hispanic or Latino participants (b = − 0.24; 95% CI = − 0.46, − 0.02), indicating that participants in these categories exhibited a stronger time-varying covariate effect of engaging in a session over the prior week. The first-order coefficient for sessions last 8–14 days also emerged as significant (b = − 0.61; 95% CI = − 0.70, − 0.52), indicating that engagement with a therapy session is associated with lower anxiety symptoms more than a week later. Participants did not differ significantly in the lagged effect of engaging in a therapy session across race and ethnicity.

Depressive symptoms

Significant first-order effects emerged for session last 7 days (b = − 0.93; 95% CI = − 1.05, − 0.81) and session last 8–14 days (b = − 0.69; 95% CI = − 0.82, − 0.57), suggesting that engaging in therapy during the past week, and the week prior were each uniquely associated with PHQ-9 scores (Table 4). All interactions of race and ethnicity with session last 7 days and session last 8–14 days failed to reach significance.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort analysis, conducted in a large racially and ethnically diverse sample of adults enrolled in BCT, found that anxiety and depressive symptoms significantly decreased during treatment across race and ethnicity. These declines were more pronounced among some racial and ethnic groups. That is, compared to White participants, Hispanic or Latino participants had greater initial decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms, while Black or African American and Asian or Pacific Islander participants had greater initial decreases in symptoms of depression alone, across treatment. Rates of reliable improvement or recovery in symptoms of anxiety or depression were high and ranged from 83.54 to 90.02% across racial and ethnic groups but statistically significant differences were observed (yet not between any two racial and ethnic groups in post-hoc tests). In addition, although participants completed approximately 6 therapy sessions on average, differences were statistically significant across racial and ethnic groups. Furthermore, average treatment satisfaction scores were high but cross-group score differences were statistically significant. Importantly, statistically significant differences across outcomes were generally small in magnitude and not clinically significant, thus this study provides evidence of equitable effectiveness of a culturally responsive BCT program across diverse racial and ethnic groups.

The current study makes important contributions to the culturally responsive psychotherapy and BCT evidence bases. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first large-scale outcomes evaluation of a culturally responsive video BCT program across racial and ethnic groups. Prior meta-analyses have reported greater effects for culturally adapted psychological interventions compared to unadapted or no psychological intervention among communities of color [44, 45], including culturally-adapted internet-based psychological interventions [17]. However, unlike the BCT program evaluated in the current study, most of the interventions included in those analyses were adapted for specific racial and ethnic groups. Such interventions may have stronger outcomes than those which are sensitive to numerous cultural contexts [46]; yet, psychological interventions that are culturally sensitive to broader populations may have more beneficial outcomes than those with no adaptations [45]. In fact, the findings of statistically significant differences across racial and ethnic groups for numerous study outcomes, though small in magnitude, point to the possibility BCT that is more broadly culturally responsive may be more beneficial for some cultural contexts than others. Further research is needed to determine the comparative effectiveness of culturally responsive BCT versus BCT with no, or varying levels of, cultural responsiveness across racial and ethnic groups. Such research should also include evaluation of BCT treatment fidelity across race and ethnicity. Despite the positive outcomes of this study, these results are not necessarily generalizable to all blended interventions, especially those that are not culturally responsive. BCT can vary by design (e.g., face-to-face versus internet module-focused BCT) [18], and the implementation strategy may also influence outcomes [47], highlighting the importance of performing outcomes evaluations of unique BCT programs, especially as such programs incorporate culturally responsive tools and expand their reach to more diverse populations. In addition, evaluating the independent effects of components of culturally responsive BCT on outcomes (e.g., culturally responsive digital tools, culturally responsive therapists) could inform the development of future programs and warrants further research.

Because digital mental health interventions could increase accessibility of care, researchers have highlighted their potential role in reducing racial and ethnic mental health disparities [13, 14]. The current study provides evidence that a large-scale BCT can be effective across communities of color. Yet, further research is needed to determine the extent to which employer-offered BCT can address mental health disparities, including evaluating additional metrics such as access and utilization rates across racial and ethnic groups [19]. The current study also found high levels of treatment satisfaction across race and ethnicity. These results extend those of a small study, which did not include race and ethnicity data, that reported high satisfaction of a video BCT program [48]. These findings are also aligned with a systematic review which found high satisfaction for tele-counseling interventions among communities of color [15]. However, the treatment satisfaction levels observed in the current study should be interpreted with caution in light of high non-response and the significant differences in final symptom severity levels between responders versus non responders. In addition, the current study did not evaluate, separately, satisfaction levels of digital tools, or the influence of satisfaction levels on clinical outcomes, both of which are important areas for future research across racial and ethnic groups. Another important area for future research is the evaluation of racial and ethnic differences in therapeutic alliance for culturally responsive BCT, and its association with outcomes.

The current study had numerous strengths. For one, this was a large racially and ethnically diverse sample. Additionally, this was a real-world evaluation that relied on measures of anxiety and depression that have been validated. However, there were several limitations. First, this study did not utilize a randomized controlled design to confirm causality, and cannot conclude that any treatment effects were attributable to the culturally responsive components of the program. Additionally, some racial and ethnic groups were under-represented in the sample and were conflated in the categories that included those who reported multiple and “Other” racial or ethnic groups. Meanwhile, a significant proportion of the sample was missing a response to the treatment satisfaction measure, and responders had significantly lower final PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores than non-responders. However, there were no significant racial and ethnic differences in the response rate for this treatment satisfaction measure. Additionally, the treatment satisfaction measure was not validated, and the possibility of racial and ethnic differences in its validity cannot be ruled out. Another limitation which may have biased study findings was missing data: 11.4% of the eligible sample was excluded from the final sample, a large proportion of which was excluded due to missing follow-up outcomes. The current study cannot preclude the possibility of regression to the mean effects, which is also a notable limitation. Yet, this study reports rates of reliable improvement, which attempts to account for measurement error, and in turn, regression to the mean effects [39, 49]. Finally, because this program was an employer-provided benefit available to employees and their dependents and the sample largely reported high levels of education as well as good or fair financial status, these results may not be generalizable to other populations.

In conclusion, it is important that large-scale digital and blended mental health interventions evaluate their ability to provide effective and equitable care across diverse racial and ethnic groups. This study demonstrated that a blended care program employing culturally responsive approaches can be beneficial for anxiety and depression outcomes across diverse racial and ethnic groups. Further research is needed to evaluate longer term outcomes of BCT across race and ethnicity. Finally, because culturally responsive care extends beyond race and ethnicity, it is important to take additional cultural and contextual factors into consideration when designing and evaluating outcomes of future blended interventions for diverse populations.

Data Availability

Because the BCT program is offered as a mental health benefit by employers, study data cannot be shared.

Code Availability

Because the study code was generated by a commercial organization, it is proprietary and cannot be shared.

References

World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JA, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:502–14.

Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:376–85.

Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:37–46.

Alonso J, Liu Z, Evans-Lacko S, Sadikova E, Sampson N, Chatterji S, et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:195–208.

Cook BL, Trinh N-H, Li Z, Hou SS-Y. Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatr Serv Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2017;68:9–16.

Twenge JM, Joiner TE. US Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:954–6.

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686.

Cai C, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Gaffney A. Trends in anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the US Census bureau’s household pulse survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:1841–3.

Thomeer MB, Moody MD, Yahirun J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2022;1–16.

Webb CA, Rosso IM, Rauch SL. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: current progress & future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25:114.

Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed E-Health. 2013;19:444–54.

Schueller SM, Hunter JF, Figueroa C, Aguilera A. Use of digital mental health for marginalized and underserved populations. Curr Treat Opt Psychiatry. 2019;6:243–55.

Ramos G, Chavira DA. Use of technology to provide mental health care for racial and ethnic minorities: evidence, promise, and challenges. Cogn Behav Pract: Elsevier; 2019.

Dorstyn DS, Saniotis A, Sobhanian F. A systematic review of telecounselling and its effectiveness in managing depression amongst minority ethnic communities. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19:338–46.

Jonassaint CR, Gibbs P, Belnap BH, Karp JF, Abebe KZ, Rollman BL. Engagement and outcomes for a computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy intervention for anxiety and depression in African Americans. BJPsych Open. 2017;3:1–5.

Ellis DM, Draheim AA, Anderson PL. Culturally adapted digital mental health interventions for ethnic/racial minorities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022;90:717.

Erbe D, Eichert H-C, Riper H, Ebert DD. Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e306.

Hernandez M, Nesman T, Mowery D, Acevedo-Polakovich ID, Callejas LM. Cultural competence: a literature review and conceptual model for mental health services. Psychiatr Serv Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2009;60:1046–50.

Callejas LM, Hernandez M. Reframing the concept of cultural competence to enhance delivery of behavioral health services to culturally diverse populations. In: Levin, B., Hanson, A. (eds) Foundations of Behavioral Health. Springer, Cham. 2020:321–35.

Edmiston KD, AlZuBi J. Trends in telehealth and its implications for health disparities. Washington, DC: National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 2022 Mar. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/Telehealth%20and%20Health%20Disparities.pdf. Accessed Oct 2022.

Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–25.

Ring JM. Psychology and medical education: collaborations for culturally responsive care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16:120–6.

Owusu JT, Wang P, Wickham RE, Varra AA, Chen C, Lungu A. Real-world evaluation of a large-scale blended care-cognitive behavioral therapy program for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Telemed E-Health. 2022;28(10):1412.

U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. 2010 Census Regions and Divisions of the United States [Internet]. U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed Oct 2022.

Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Lungu A, Jun JJ, Azarmanesh O, Leykin Y, Chen CE-J. Blended care-cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety in real-world settings: pragmatic retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e18723.

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy, second edition: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

Linehan MM. DBT Skills Training Manual Second Edition. Second Edition, Available separately: DBT skills training handouts and worksheets. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2014.

Goodwin BJ, Coyne AE, Constantino MJ. Extending the context-responsive psychotherapy integration framework to cultural processes in psychotherapy. Psychother. 2018;55:3.

Sue S, Zane N, Nagayama Hall GC, Berger LK. The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:525–48.

Zerbe Enns C, Díaz LC, Bryant-Davis T. Transnational Feminist Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Women Ther. 2021;44:11–26.

Basham K. Weaving a tapestry: Anti‐racism and the pedagogy of clinical social work practice. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work 2004; 74:289–314

Singh AA. The racial healing handbook: practical activities to help you challenge privilege, confront systemic racism, and engage in collective healing. New Harbinger Publications; 2019.

Bryant-Davis T, Ocampo C. A therapeutic approach to the treatment of racist-incident-based trauma. J Emot Abuse Taylor & Francis. 2006;6:1–22.

Goodman DJ. Promoting diversity and social justice: educating people from privileged groups. Routledge; 2011.

Nadal KL. A guide to responding to microaggressions. CUNYforum; 2014.

Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–9.

Gyani A, Shafran R, Layard R, Clark DM. Enhancing recovery rates: lessons from year one of IAPT. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:597–606.

Reichheld FF. The one number you need to grow. Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81:46–55.

Maxwell SE, Delaney HD, Kelley K. Designing experiments and analyzing data: a model comparison perspective. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge; 2018.

Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Arundell L-L, Barnett P, Buckman JE, Saunders R, Pilling S. The effectiveness of adapted psychological interventions for people from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review and conceptual typology. Clin Psychol Rev Elsevier. 2021;88:102063.

Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 2006;43:531 (Educational Publishing Foundation).

Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: a direct-comparison meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:279.

Kenter RM, van de Ven PM, Cuijpers P, Koole G, Niamat S, Gerrits RS, et al. Costs and effects of internet cognitive behavioral treatment blended with face-to-face treatment: results from a naturalistic study. Internet Interv Elsevier. 2015;2:77–83.

Etzelmueller A, Radkovsky A, Hannig W, Berking M, Ebert DD. Patient’s experience with blended video-and internet based cognitive behavioural therapy service in routine care. Internet Interv. 2018;12:165–75.

Kenny DA, Campbell DT. A primer on regression artifacts. NY: NY Guilford; 1999.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Monica Wu, PhD for her thoughtful review of the study manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T.O., C.C., and A.L. contributed to the study conception. P.W. and R.E.W. performed the data analysis and verified the underlying study data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of study results and manuscript preparation and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This analysis was determined exempt by the WCG Institutional Review Board (Puyallup, WA).

Consent to Participate

All participants provided consent to take part in BCT and have their de-identified data used for research purposes.

Conflict of Interest

J.T.O., P.W., D.P.C., A.A.V., C.C., and A.L. are employees of, receive salary from, and have been granted equity in, Lyra Health, Inc. A.A.V., D.P.C., and C.C. are also employees of, and receive salary from, Lyra Clinical Associates. R.E.W. serves as a paid consultant to Lyra Health.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Owusu, J.T., Wang, P., Wickham, R.E. et al. Blended Care Therapy for Depression and Anxiety: Outcomes across Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 2731–2743 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01450-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01450-z