Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review emerges from the necessity to gather information of quality on the possibility to directly modulate macrophages and its functions to improve cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment in order to improve the lesions of the infection without leaving a disfiguring scar.

Recent Findings

Cutaneous leishmaniasis often leaves disfiguring scars, a fact associated with improper infection resolution related to an inappropriate action of the macrophages. As these cells are the main target of Leishmania spp., these parasites subvert macrophages’ response to avoid a pro-inflammatory profile, with interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumoural necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and induce an anti-inflammatory with the participation of IL-10. These are one of the many strategies that different species of Leishmania spp. used to escape the immune response, which also includes reducing oxidative stress and parasite killing. The use of immune mediators to induce pro-inflammatory macrophages has been showing success into eliminating the parasites and promoting a proper resolution of the infection.

Summary

The treatment of CL often eliminates the parasites; however, beyond its cytotoxicity, it takes time and still a disfiguring scar remain. Therefore, the treatment should be based on several aspects such as the clinical manifestation, localization of the lesions, and the possibility to integrate other medications beyond focusing only on parasite killing. Thus, the treatment aiming the modulation of the immune system together with traditional treatments, given that Leishmania can interfere in the pro-inflammatory pathway of the macrophages, could represent an alternative strategy to promote complete closure of the lesions without disfiguring scar.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lestinova T, Rohousova I, Sima M, de Oliveira CI, Volf P. Insights into the sand fly saliva: blood-feeding and immune interactions between sand flies, hosts, and Leishmania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005600.

Reithlinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581–96.

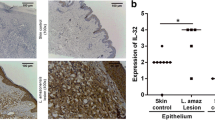

Christensen SM, Belew AT, El-Sayed NM, Tafuri WL, Silveira FT, Mosser DM. Host and parasite responses in human diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. amazonensis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;13:1–23.

Mcgwire BS, Satoskar AR. Leishmaniasis: clinical syndromes and treatment. QJM. 2014;107:7–14.

Davies CR, Reithinger R, Campbell-Lendrum D, Feliciangeli D, Borges R, Rodriguez N. The epidemiology and control of leishmaniasis in Andean countries. Cad saúde pública / Ministério da Saúde, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Esc Nac Saúde Pública. 2000;16:925–50.

Bennis I, De Brouwere V, Belrhiti Z, Sahibi H, Boelaert M. Psychosocial burden of localised cutaneous leishmaniasis: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–12.

Palić S, Beijnen JH, Dorlo TPC. An update on the clinical pharmacology of miltefosine in the treatment of leishmaniasis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2022;59:1–6.

Rogers ME. The role of Leishmania proteophosphoglycans in sand fly transmission and infection of the mammalian host. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:1–13.

Peters NC, Egen JG, Secundino N, Debrabant A, Kamhawi S, Lawyer P, et al. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science (80- ). 2008;321:970–4.

Chagas AC, Oliveira F, Debrabant A, Valenzuela JG, Ribeiro JMC, Calvo E. Lundep, a sand fly salivary endonuclease increases Leishmania parasite survival in neutrophils and inhibits XIIa contact activation in human plasma. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(2):e1003923.

Abdeladhim M, Kamhawi S, Valenzuela JG. What’s behind a sand fly bite? The profound effect of sand fly saliva on host hemostasis, inflammation and immunity. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;28:691–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2014.07.028

Passelli K, Billion O, Tacchini-Cottier F. The impact of neutrophil recruitment to the skin on the pathology induced by Leishmania infection. Front Immunol. 2021;12:1–12.

Naderer T, McConville MJ. The Leishmania-macrophage interaction: a metabolic perspective. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:301–8.

Zer R, Yaroslavski I, Rosen L, Warburg A. Effect of sand fly saliva on Leishmania uptake by murine macrophages. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:810–4.

Bee A, Culley FJ, Alkhalife IS, Bodman-Smith KB, Raynes JG, Bates PA. Transformation of Leishmania mexicana metacyclic promastigotes to amastigote-like forms mediated by binding of human C-reactive protein. Parasitology. 2001;122:521–9.

Sunter J, Gull K. Shape, form, function and Leishmania pathogenicity: from textbook descriptions to biological understanding. Open Biol. 2017;7(8):170165.

Dos Santos FC, Silveira Martins P, Demicheli C, Brochu C, Ouellette M, Frézard F. Thiol-induced reduction of antimony(V) into antimony(III): a comparative study with trypanothione, cysteinyl-glycine, cysteine and glutathione. Biometals. 2003;16:441–6.

Olivier M, Gregory DJ, Forget G. Subversion mechanisms by which Leishmania parasites can escape the host immune response: a signaling point of view. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:293–305.

Mehwish S, Khan H, Rehman AU, Khan AU, Khan MA, Hayat O, et al. Natural compounds from plants controlling leishmanial growth via DNA damage and inhibiting trypanothione reductase and trypanothione synthetase: an in vitro and in silico approach. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:1–14.

Rogers M, Kropf P, Choi BS, Dillon R, Podinovskaia M, Bates P, et al. Proteophosphoglycans regurgitated by Leishmania-infected sand flies target the L-arginine metabolism of host macrophages to promote parasite survival. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(8):e1000555.

Crosby EJ, Goldschmidt MH, Wherry EJ, Scott P. Engagement of NKG2D on bystander memory CD8 T cells promotes increased immunopathology following Leishmania major infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(2):e1003970.

Tomiotto-pellissier F, Taciane B, Assolini JP. Macrophage polarization in leishmaniasis : broadening horizons. 2018;9:1–12.

Stafford JL, Neumann NF, Belosevic M. Macrophage-mediated innate host defense against protozoan parasites. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2002;28:187–248.

•• Loría-Cervera EN, Andrade-Narvaez F. The role of monocytes/macrophages in Leishmania infection: a glance at the human response. Acta Trop. 2020;207:105456. This article shows the huge importance of macrophages in the pathogenesis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Still, highlight how these parasites subvert macrophages to maintain the infections.

Scott P, Novais FO. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: immune responses in protection and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:581–92.

Kane MM, Mosser DM. The role of IL-10 in promoting disease progression in leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2001;166:1141–7.

Sadick MD, Heinzel FP, Holaday BJ, Pu RT, Dawkins RS, Locksley RM. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon γ-independent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1990;171:115–27.

Melby PC, Andrade-Narvaez FJ, Darnell BJ, Valencia-Pacheco G, Tryon VV, Palomo-Cetina A. Increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines in chronic lesions of human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:837–42.

Costa DL, Cardoso TM, Queiroz A, Milanezi CM, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM, et al. Tr-1-like CD4+CD25- CD127-/lowFOXP3- cells are the main source of interleukin 10 in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:708–18.

Gonçalves de Albuquerque S da C, da Costa Oliveira CN, Vaitkevicius-Antão V, Silva AC, Luna CF, de Lorena VMB, et al. Study of association of the rs2275913 IL-17A single nucleotide polymorphism and susceptibility to cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis. Cytokine. 2019;123:154784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154784.

Guimarães-Costa AB, Nascimento MTC, Froment GS, Soares RPP, Morgado FN, Conceição-Silva F, et al. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6748–53.

Ritter U, Frischknecht F, van Zandbergen G. Are neutrophils important host cells for Leishmania parasites? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:505–10.

Manamperi NH, Oghumu S, Pathirana N, Silva VC De, Abeyewickreme W, Satoskar AR, et al. In situ immunopathological changes in cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani. 2018;39:1–20.

Ji J, Sun J, Qi HAI, Soong L. Analysis of t helper cell responses during infection with Leishmania amazonensis. Trop Med. 2002;66:338–45.

Gurung P, Karki R, Vogel P, Watanabe M, Bix M, Lamkanfi M, et al. An NLRP3 inflammasome’ triggered Th2-biased adaptive immune response promotes leishmaniasis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1329–38.

Patil T, More V, Rane D, Mukherjee A, Suresh R, Patidar A, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) controls Leishmania infection. Cytokine. 2018;112:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.06.033.

Kihel A, Hammi I, Darif D, Lemrani M, Riyad M, Guessous F, et al. The different faces of the NLRP3 inflammasome in cutaneous leishmaniasis: a review. Cytokine. 2021;147:155248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155248.

Santos D, Campos TM, Saldanha M, Oliveira SC, Nascimento M, Zamboni DS, et al. IL-1β Production by intermediate monocytes is associated with immunopathology in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1107–15.

Louis L, Clark M, Wise MC, Glennie N, Andrea W, Broderick K, et al. Intradermal synthetic DNA vaccination generates Leishmania-specific T cells in the skin and protection against Leishmania major. Infect Immun. 2019;87:1–14.

Tomiotto-Pellissier F, Miranda-Sapla MM, Silva TF, Bortoleti BT da S, Gonçalves MD, Concato VM, et al. Murine susceptibility to Leishmania amazonensis infection is influenced by arginase-1 and macrophages at the lesion site. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:1–14.

Basmaciyan L, Casanova M. Cell death in Leishmania. Parasite. 2019;26:71.

Lakhal-Naouar I, Slike BM, Aronson NE, Marovich MA. The immunology of a healing response in cutaneous leishmaniasis treated with localized heat or systemic antimonial therapy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:1–17.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Manual De Vigilância Da Leishmaniose Tegumentar. Man. vigilância da leishmaniose tegumentar. 2017.

Oliveira LF, Schubach AO, Martins MM, Passos SL, Oliveira RV, Marzochi MC, et al. Systematic review of the adverse effects of cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment in the New World. Acta Trop. 2011;118:87–96.

Gonzalez-Fajardo L, Fernández OL, McMahon-Pratt D, Saravia NG. Ex vivo host and parasite response to antileishmanial drugs and immunomodulators. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(5):e0003820.

de Saldanha RR, Martins-Papa MC, Sampaio RNR, Muniz-Junqueira MI. Meglumine antimonate treatment enhances phagocytosis and TNF-α production by monocytes in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:596–603.

Macedo SRA, De Figueiredo Nicolete LD, Ferreira ADS, De Barros NB, Nicolete R. The pentavalent antimonial therapy against experimental Leishmania amazonensis infection is more effective under the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28:554–9.

Muniz-Junqueira MI, de Paula-Coelho VN. Meglumine antimonate directly increases phagocytosis, superoxide anion and TNF-α production, but only via TNF-α it indirectly increases nitric oxide production by phagocytes of healthy individuals, in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1633–8.

El-Housseiny GS, Ibrahim AA, Yassien MA, Aboshanab KM. Production and statistical optimization of paromomycin by Streptomyces rimosus NRRL 2455 in solid state fermentation. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:34.

Moradzadeh R, Golmohammadi P, Ashraf H, Nadrian H, Fakoorziba MR. Effectiveness of paromomycin on cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Med Sci. 2019;44:185–95.

Soto J, Soto P, Ajata A, Luque C, Tintaya C, Paz D, et al. Topical 15% paromomycin-aquaphilic for Bolivian Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:844–9.

el-On J, Weinrauch L, Livshin R, Even-Paz Z, Jacobs GP. Topical treatment of recurrent cutaneous leishmaniasis with ointment containing paromomycin and methylbenzethonium chloride. BMJ. 1985;291:704–5.

Maarouf M, de Kouchkovsky Y, Brown S, Petit PX, Robert-Gero M. In vivo interference of paromomycin with mitochondrial activity of Leishmania. Exp Cell Res. 1997;232:339–48.

Sundar S, Chakravarty J, Meena LP. Leishmaniasis: treatment, drug resistance and emerging therapies. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2019;7:1–10.

Paris C, Loiseau PM, Bories C, Bréard J. Miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:852–9.

Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R. Therapeutic options for visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs. 2013;73:1863–88.

Soto J, Berman J. Treatment of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis with miltefosine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:34–40.

Machado PR, Ampuero J, Guimarães LH, Villasboas L, Rocha AT, Schriefer A, et al. Miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis in Brazil: a randomized and controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:1–6.

Ware JM, O’Connell EM, Brown T, Wetzler L, Talaat KR, Nutman TB, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e2457–562.

Roatt BM, de Oliveira Cardoso JM, De Brito RCF, Coura-Vital W, de Oliveira Aguiar-Soares RD, Reis AB. Recent advances and new strategies on leishmaniasis treatment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:8965–77.

Jha SN, Singh NK, Jha TK. Changing response to diamidine compounds in cases of kala-azar unresponsive to antimonial. J Assoc Physicians India. 1991;39:314–6.

Neves LO, Talhari AC, Gadelha EPN, Silva Júnior RM da, Guerra JA de O, Ferreira LC de L, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine and amphotericin B for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis by Leishmania guyanensis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1092–101.

Hafiz S, Kyriakopoulos C. Pentamidine. StatPearls. 2022.

•• André S, Rodrigues V, Pemberton S, Laforge M, Fortier Y, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, et al. Antileishmanial drugs modulate IL-12 expression and inflammasome activation in primary human cells. J Immunol. 2020;204:1869–80. This paper clarified the action of the antileishmanial drugs amphotericin B, miltefosine, and pentamidine on human monocytes.

Calegari-Silva TC, Vivarini ÁC, Pereira R de MS, Dias-Teixeira KL, Rath CT, Pacheco ASS, et al. Leishmania amazonensis downregulates macrophage iNOS expression via histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1): a novel parasite evasion mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48:1188–98.

Gray KC, Palacios DS, Dailey I, Endo MM, Uno BE, Wilcock BC, et al. Amphotericin primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2234–9.

Balasegaram M, Ritmeijer K, Lima MA, Burza S, Ortiz Genovese G, Milani B, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B as a treatment for human leishmaniasis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2012;17:493–510.

Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, Davidson RN. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203–5.

Solomon M, Pavlotzky F, Barzilai A, Schwartz E. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis in travelers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:284–9.

Motta JOC, Sampaio RNR. A pilot study comparing low-dose liposomal amphotericin B with N-methyl glucamine for the treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:331–5.

Layegh P, Rajabi O, Jafari MR, Emamgholi Tabar Malekshah P, Moghiman T, Ashraf H, et al. Efficacy of topical liposomal amphotericin B versus intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Parasitol Res. 2011;2011:1–5.

Mukherjee AK, Gupta G, Bhattacharjee S, Guha SK, Majumder S, Adhikari A, et al. Amphotericin B regulates the host immune response in visceral leishmaniasis: reciprocal regulation of protein kinase C isoforms. J Infect. 2010;61:173–84.

Ehrenfreund-Kleinman T, Domb AJ, Jaffe CL, Nasereddin A, Leshem B, Golenser J. The effect of amphotericin b derivatives on Leishmania and immune functions. J Parasitol. 2005;91:158–63.

Wadhone P, Maiti M, Agarwal R, Kamat V, Martin S, Saha B. Miltefosine promotes IFN-γ-dominated anti-leishmanial immune response. J Immunol. 2009;182:7146–54.

Tavares GSV, Mendonça DVC, Pereira IAG, Oliveira-Da-Silva JA, Ramos FF, Lage DP, et al. A clioquinol-containing Pluronic®F127 polymeric micelle system is effective in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in a murine model. Parasite. 2020;27:29.

Ghosh M, Roy K, Roy S. Immunomodulatory effects of antileishmanial drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2834–8.

Mukhopadhyay D, Mukherjee S, Roy S, Dalton JE, Kundu S, Sarkar A, et al. M2 Polarization of monocytes-macrophages is a hallmark of Indian post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:1–19.

Taslimi Y, Zahedifard F, Rafati S. Leishmaniasis and various immunotherapeutic approaches. Parasitology. 2018;145:497–507.

León B, López-Bravo M, Ardavín C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26:519–31.

Siewe N, Yakubu A-A, Satoskar AR, Friedman A. Immune response to infection by Leishmania: a mathematical model. Math Biosci. 2016;276:28–43.

Ribeiro-gomes FL, Romano A, Lee S, Roffê E, Peters NC, Debrabant A, et al. Apoptotic cell clearance of Leishmania major- infected neutrophils by dendritic cells inhibits CD8 + T-cell priming in vitro by Mer tyrosine kinase-dependent signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:1–12.

Ashok D, Acha-Orbea H. Timing is everything: dendritic cell subsets in murine Leishmania infection. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:499–507.

Romano A, Carneiro MBH, Doria NA, Roma EH, Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Inbar E, et al. Divergent roles for Ly6C+CCR2+CX3CR1+inflammatory monocytes during primary or secondary infection of the skin with the intra-phagosomal pathogen Leishmania major. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:1–26.

Abdeladhim M, Ahmed M, Marzouki S, Hmida NB, Boussoffara T, Hamida NB, et al. Human cellular immune response to the saliva of Phlebotomus papatasi is mediated by IL-10-producing CD8+ T cells and TH1-polarized CD4+ lymphocytes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(10):e1345.

Gabriel Á, Valério-Bolas A, Palma-Marques J, Mourata-Gonçalves P, Ruas P, Dias-Guerreiro T, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: the complexity of host’s effective immune response against a polymorphic parasitic disease. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:1–16.

Calegari-Silva TC, Pereira RMS, De-Melo LDB, Saraiva EM, Soares DC, Bellio M, et al. NF-κB-mediated repression of iNOS expression in Leishmania amazonensis macrophage infection. Immunol Lett. 2009;127:19–26.

Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. IκB kinases: key regulators of the NF-κB pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:72–9.

Gregory DJ, Godbout M, Contreras I, Forget G, Olivier M. A novel form of NF-κB is induced by Leishmania infection: involvement in macrophage gene expression. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1071–81.

•• Muxel SM, Laranjeira-Silva MF, Zampieri RA, Floeter-Winter LM. Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis induces macrophage miR-294 and miR-721 expression and modulates infection by targeting NOS2 and L-arginine metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–15. Muxel et al., describes and proves the importance of nitrite in the pathogenesis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Because of that, it shows that modulating this pathway could be of importance to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Volpedo G, Pacheco-fernandez T, Holcomb EA, Cipriano N. Mechanisms of immunopathogenesis in cutaneous leishmaniasis and post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). 2021;11:1–16.

Liu D, Uzonna JE. The early interaction of Leishmania with macrophages and dendritic cells and its influence on the host immune response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:83.

Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–54.

Kane MM, Mosser DM. Leishmania parasites and their ploys to disrupt macrophage activation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7:26–31.

Ikeogu NM, Akaluka GN, Edechi CA, Salako ES, Onyilagha C, Barazandeh AF, et al. Leishmania immunity: advancing immunotherapy and vaccine development. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1–21.

Heinzel FP, Schoenhaut DS, Rerko RM, Rosser LE, Gately MK. Recombinant interleukin 12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1505–9.

Castellano LR, Argiro L, Dessein H, Dessein A, Da Silva MV, Correia D, et al. Potential use of interleukin-10 blockade as a therapeutic strategy in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:1–5.

Bourreau E, Ronet C, Darcissac E, Lise MC, Marie D Sainte, Clity E, et al. Intralesional regulatory T-Cell suppressive function during human acute and chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1465–74.

Li J, Sutterwala S, Farrell JP. Successful therapy of chronic, nonhealing murine cutaneous leishmaniasis with sodium stibogluconate and gamma interferon depends on continued interleukin-12 production. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3225–30.

Khalili G, Dobakhti F, Niknam HM, Khaze V, Partovi F. Immunotherapy with imiquimod increases the efficacy of Glucantime therapy of Leishmania major infection. Iran J Immunol. 2011;8:45–51.

da Fonseca-Martins AM, Ramos TD, Pratti JES, Firmino-Cruz L, Gomes DCO, Soong L, et al. Immunotherapy using anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 in Leishmania amazonensis-infected BALB/c mice reduce parasite load. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–13.

Buates S, Matlashewski G. Treatment of experimental leishmaniasis with the immunomodulators imiquimod and S-28463: efficacy and mode of action. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1485–94.

Miranda-Verástegui C, Llanos-Cuentas A, Arévalo I, Ward BJ, Matlashewski G. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial of topical imiquimod 5% with parenteral meglumine antimoniate in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Peru. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1395–403.

Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:984–93.

Testerman TL, Gerster JF, Imbertson LM, Reiter MJ, Miller RL, Gibson SJ, et al. Cytokine induction by the immunomodulators imiquimod and S-27609. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:365–72.

Arevalo I, Ward B, Miller R, Meng TC, Najar E, Alvarez E, et al. Successful treatment of drug-resistant cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans by use of imiquimod, an immunomodulator. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1847–51.

dos Santos JC, Barroso de Figueiredo AM, Teodoro Silva MV, Cirovic B, de Bree LCJ, Damen MSMA, et al. β-glucan-induced trained immunity protects against Leishmania braziliensis infection: a crucial role for IL-32. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2659–2672.e6.

Brito G, Dourado M, Guimarães LH, Meireles E, Schriefer A, De Carvalho EM, et al. Oral pentoxifylline associated with pentavalent antimony: a randomized trial for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1155–9.

Brito G, Dourado M, Polari L, Celestino D, Carvalho LP, Queiroz A, et al. Clinical and immunological outcome in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients treated with pentoxifylline. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:617–20.

De Faria DR, Barbieri LC, Koh CC, Machado PRL, Barreto CC, De Lima CMF, et al. In situ cellular response underlying successful treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis with a combination of pentavalent antimonial and pentoxifylline. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101:392–401.

De Sá OT, Neto MC, Martins BJA, Rodrigues HA, Antonino RMP, Magalhães AV. Action of pentoxifylline on experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:477–82.

Parvizi MM, Handjani F, Moein M, Hatam G, Nimrouzi M, Hassanzadeh J, et al. Efficacy of cryotherapy plus topical Juniperus excelsa M. Bieb cream versus cryotherapy plus placebo in the treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: a triple-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:1–23.

Tasdemir D, Kaiser M, Brun R, Yardley V, Schmidt TJ, Tosun F, et al. Antitrypanosomal and antileishmanial activities of flavonoids and their analogues: in vitro, in vivo, structure-activity relationship, and quantitative structure-activity relationship studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1352–64.

•• Staffen IV, Banhuk FW, Tomiotto-Pellissier F, da Silva Bortoleti BT, Pavanelli WR, Ayala TS, et al. Chalcone-rich extracts from Lonchocarpus cultratus roots present in vitro leishmanicidal and immunomodulatory activity . J Pharm Pharmacol. 2022;74:77–87. The authors here present an extract with potent anti-leishmanial effect. Together with that, they show that these different extracts improves the activity of macrophages to kill amastigotes of Leishmania amazonensis.

de Souza JH, Michelon A, Banhuk FW, Staffen IV, Klein EJ, da Silva EA, et al. Leishmanicidal, trypanocidal and antioxidant activity of amyrin-rich extracts from Eugenia pyriformis Cambess. Iran J Pharm Res. 2020;19:343–53.

Tafazzoli Z, Nahidi Y, Mashayekhi Goyonlo V, Morovatdar N, Layegh P. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of vascular IPL for treatment of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2021;36:631–40.

Shahi M, Mohajery M, Shamsian SAA, Nahrevanian H, Yazdanpanah SMJ. Comparison of Th1 and Th2 responses in non-healing and healing patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Reports Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;1:43–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26989708/; http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4757055. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Pivotto AP, Banhuk FW, Staffen IV, Daga MA, Ayala TS, Menolli RA. Clinical uses and molecular aspects of ozone therapy: a review. Online J Biol Sci. 2020;20:37–49.

• Cabral IL, Utzig SL, Banhuk FW, Staffen IV, Loth EA, de Amorim JPA, et al. Aqueous ozone therapy improves the standard treatment of leishmaniasis lesions in animals leading to local and systemic alterations. Parasitol Res. 2020;119:4243–53. This paper describes for the first time, how aqueous ozone therapy improves the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in mice. Background evidence shows that ozone leads to antioxidant effect on macrophages.

Aghaei M, Aghaei S, Sokhanvari F, Ansari N, Hosseini SM, Mohaghegh M, et al. The therapeutic effect of ozonated olive oil plus glucantime on human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019;22:25–30.

Nascimento E, Fernandes DF, Vieira EP, Campos-Neto A, Ashman JA, Alves FP, et al. A clinical trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the LEISH-F1+MPL-SE vaccine when used in combination with meglumine antimoniate for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2010;28:6581–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.063.

Zahedifard F, Rafati S. Prospects for antimicrobial peptide-based immunotherapy approaches in Leishmania control. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16:461–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2018.1483720

Pérez-Cordero JJ, Lozano JM, Cortés J, Delgado G. Leishmanicidal activity of synthetic antimicrobial peptides in an infection model with human dendritic cells. Peptides. 2011;32:683–90.

Barroso PA, Marco JD, Calvopina M, Kato H, Korenaga M, Hashiguchi Y. A trial of immunotherapy against Leishmania amazonensis infection in vitro and in vivo with Z-100, a polysaccharide obtained from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, alone or combined with meglumine antimoniate. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1123–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Funding

TSA receives a fellowship from CAPES.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LBSL: Drafting the article, Acquisition of data; RAM: Acquisition of data, Analysis, and interpretation of data TSA: Conception and design of the study, Acquisition of data, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Neglected Diseases of the Americas

The authors Rafael Andrade Menolli and Thais Soprani Ayala did contribute equally as corresponding author.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza Lima, L.B., Menolli, R.A. & Ayala, T.S. Immunomodulation of Macrophages May Benefit Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Outcome. Curr Trop Med Rep 10, 281–294 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-023-00303-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-023-00303-x