Abstract

Objective

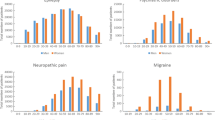

Our aim was to explore trends in price evolution and prescription volumes of anticonvulsants (AEDs, antiepileptic drugs) in Germany between 2000 and 2017.

Method

This study used data from annual reports on mean prescription frequency and prices of defined daily doses (DDD) of AEDs in Germany to analyze nationwide trends. Interrupted time series (ITS) analysis was employed to test for significant effects of several statutory healthcare reforms in Germany on AED price evolution. These data were compared to cohort-based prescription patterns of four German cohort studies from 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2016 that included a total of 1368 patients with focal and generalized epilepsies.

Results

Analysis of national prescription data between 2000 and 2017 showed that mean prices per DDD of third-generation AEDs decreased by 65% and mean prices of second-generation AEDs decreased by 36%, whereas mean prices of first-generation AEDs increased by 133%. Simultaneously, mean prescription frequency of third- generation AEDs increased by 2494%, while there was a substantial decrease in the use of first- (− 55%) and second- (− 16%) generation AEDs. ITS analysis revealed that in particular the introduction of mandatory rebates on drugs in 2003 affected prices of frequently used newer AEDs. These findings are consistent with data from cohort studies of epilepsy patients showing a general decrease of prices for frequently used AEDs in monotherapy by 62% and in combination therapies by 68%. The analysis suggests that overall expenses for AEDs remained stable despite an increase in the prescription of “newer” and “non-enzyme-inducing” AEDs for epilepsy patients.

Conclusion

Between 2000 and 2017, a distinct decline in AED prices can be observed that seems predominately caused by a governmentally obtained price decline of third- and second-generation drugs. These observations seem to be the result of a German statutory cost containment policy applied across all health-care sectors. The increasing use of third-generation AEDs to the disadvantage of “old” and “enzyme-inducing” AEDs reflects the preferences of physicians and patients with epilepsy and follows national treatment guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability statement

National prescription frequency and prices: The data that support the findings of this part of the study have been fully published in the annual ‘Arzneiverordnungs-Reports’ by Ulrich Schwabe, Dieter Pfaffrath, Wolf-Dieter Ludwig, and Jürgen Klauber, and are accessible as digital or printed version of the annual ‘Arzneiverordnungs-Report’, published by Springer Verlag Deutschland GmbH. Data for the cohort studies: The data that support the findings of this part of the study are available from the corresponding author [AS], and anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions by the local ethics commissions prohibiting the publication of unprocessed data that could compromise research participant privacy.

References

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–602.

Strzelczyk A, Reese JP, Dodel R, et al. Cost of epilepsy: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26:463–76.

Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE Official Report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475–82.

Willems L, Richter S, Watermann N, et al. Trends in resource utilization and prescription of anticonvulsants for patients with active epilepsy in Germany from 2003 to 2013—a ten-year overview. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;83:28–35.

Hamer HM, Dodel R, Strzelczyk A, et al. Prevalence, utilization, and costs of antiepileptic drugs for epilepsy in Germany—a nationwide population-based study in children and adults. J Neurol. 2012;259:2376–84.

Hamer HM, Spottke A, Aletsee C, et al. Direct and indirect costs of refractory epilepsy in a tertiary epilepsy center in Germany. Epilepsia. 2006;47:2165–72.

Strzelczyk A, Haag A, Reese JP, et al. Trends in resource utilization and prescription of anticonvulsants for patients with active epilepsy in Germany. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:433–8.

Strzelczyk A, Ansorge S, Hapfelmeier J, et al. Costs, length of stay, and mortality of super-refractory status epilepticus: A population-based study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1533–41.

Schubert-Bast S, Zöllner JP, Ansorge S, et al. Burden and epidemiology of status epilepticus in infants, children, and adolescents: A population-based study on German health insurance data. Epilepsia. 2019;60:911–20.

Riechmann J, Strzelczyk A, Reese JP, et al. Costs of epilepsy and cost-driving factors in children, adolescents, and their caregivers in Germany. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1388–97.

von der Schulenburg G, Uber A. Current issues in German healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;12:517–23.

Steinbronn R. 18 months law for the modernisation of the SHI—review and prospects. Z Kardiol. 2005;94:15–8.

Herr A. Wettbewerb und Rationalisierung im deutschen Arzneimittelmarkt: ein Überblick. List Forum für Wirtschafts- und Finanzpolitik. 2013;39:163–81.

Strzelczyk A. Hamer HM [Impact of early benefit assessment on patients with epilepsy in Germany: current healthcare provision and therapeutic needs]. Nervenarzt. 2016;87:386–93.

Ruof J, Schwartz FW, Schulenburg JM, et al. Early benefit assessment (EBA) in Germany: analysing decisions 18 months after introducing the new AMNOG legislation. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15:577–89.

Duerden MG. Generic substitution. Reimbursement requires reform. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2010;341:c3566.

Duerden MG, Hughes DA. Generic and therapeutic substitutions in the UK: are they a good thing? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:335–41.

Kadel J, Bauer S, Hermsen AM, et al. Use of Emergency Medication in Adult Patients with Epilepsy: a Multicentre Cohort Study from Germany. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:771–81.

Strzelczyk A, Nickolay T, Bauer S, et al. Evaluation of health-care utilization among adult patients with epilepsy in Germany. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:451–7.

Willems LM, Richter S, Watermann N, et al. Trends in resource utilization and prescription of anticonvulsants for patients with active epilepsy in Germany from 2003 to 2013—a ten-year overview. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;83:28–35.

Knake S, Rosenow F, Vescovi M, et al. Incidence of status epilepticus in adults in Germany: a prospective, population-based study. Epilepsia. 2001;42:714–8.

Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522–30.

Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:512–21.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18:800–4.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885.

Pfannkuche M, Glaeske G, Neye H, et al. Kostenvergleiche für Arzneimittel auf der Basis von DDD im Rahmen der Vertragsärztlichen Versorgung. Gesundh ökon Qual manag. 2009;2009:17–23.

Bock JO, Brettschneider C, Seidl H, et al. Calculation of standardised unit costs from a societal perspective for health economic evaluation. Gesundheitswesen. 2015;77:53–61.

Krauth C, Hessel F, Hansmeier T, et al. Empirical standard costs for health economic evaluation in Germany—a proposal by the working group methods in health economic evaluation. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:736–46.

Schwabe U. Antiepileptika. In: Schwabe U, Pfaffrath D, Ludwig W-D, et al., eds., Arzneiverordnungs-Report. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag GmbH, 2001-2018

Löscher W, Schmidt D. Modern antiepileptic drug development has failed to deliver: ways out of the current dilemma. Epilepsia. 2011;52:657–78.

Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, et al. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:950–6.

Koskinen H, Mikkola H, Saastamoinen LK, et al. Time series analysis on the impact of generic substitution and reference pricing on antipsychotic costs in Finland. Value Health. 2015;18:1105–12.

Strzelczyk A, Griebel C, Lux W, et al. The Burden of Severely Drug-Refractory Epilepsy: A Comparative Longitudinal Evaluation of Mortality, Morbidity, Resource Use, and Cost Using German Health Insurance Data. Front Neurol. 2017;8:712.

Adelson PD, Black PM, Madsen JR, et al. Use of subdural grids and strip electrodes to identify a seizure focus in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995;22:174–80.

Gollwitzer S, Kostev K, Hagge M, et al. Nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs in Germany: a retrospective, population-based study. Neurology. 2016;87:466–72.

Elger C, Berkenfeld R. S1-Leitlinie Erster epileptischer Anfall und Epilepsien im Erwachsenenalter., Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie: Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie, 2017.

Ertl J, Hapfelmeier J, Peckmann T, et al. Guideline conform initial monotherapy increases in patients with focal epilepsy: a population-based study on German health insurance data. Seizure. 2016;41:9–15.

Strzelczyk A, Bergmann A, Biermann V, et al. Neurologist adherence to clinical practice guidelines and costs in patients with newly diagnosed and chronic epilepsy in Germany. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:75–82.

French J, Glue P, Friedman D, et al. Adjunctive pregabalin vs gabapentin for focal seizures: interpretation of comparative outcomes. Neurology. 2016;87:1242–9.

Goodman CW, Brett AS. Gabapentin and pregabalin for pain—is increased prescribing a cause for concern? N Engl J Med. 2017;377:411–4.

European Medicines Agency. PRAC recommends strengthening the restrictions on the use of valproate in women and girls. 2014. EMA/612389/2014

Virta LJ, Kalviainen R, Villikka K, et al. Declining trend in valproate use in Finland among females of childbearing age in 2012-2016—a nationwide registry-based outpatient study. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:869–74.

Mole TB, Appleton R, Marson A. Withholding the choice of sodium valproate to young women with generalised epilepsy: are we causing more harm than good? Seizure. 2015;24:127–30.

Nariai H, Duberstein S, Shinnar S. Treatment of epileptic encephalopathies: current state of the art. J Child Neurol. 2018;33:41–54.

Kortland LM, Alfter A, Bähr O, et al. Costs and cost-driving factors for acute treatment of adults with status epilepticus: a multicenter cohort study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2016;57:2056–66.

Dorks M, Langner I, Timmer A, et al. Treatment of paediatric epilepsy in Germany: antiepileptic drug utilisation in children and adolescents with a focus on new antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Res. 2013;103:45–53.

Graf J. The effects of rebate contracts on the health care system. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15:477–87.

Natz A. Rebate contracts: risks and chances in the German generic market. J Generic Med. 2008;5:99–103.

Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung, Vorläufige Rechnungsergebnisse, 1.-4. Quartal 2016. Berlin, 2017.

Brungs S. Gesundheitsausgaben im Jahr 2015 um 4,5 % gestiegen. [Health expenditure increase by 4.5% in 2015.] DeSTATIS: Pressemitteilung Nr. 061 vom 21. Februar 2017; Berlin, 2017. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2017/02/PD17_061_23611.html

Welty TE, Pickering PR, Hale BC, et al. Loss of seizure control associated with generic substitution of carbamazepine. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:775–7.

Wyllie E, Pippenger CE, Rothner AD. Increased seizure frequency with generic primidone. JAMA. 1987;258:1216–7.

Berg MJ, Gross RA, Tomaszewski KJ, et al. Generic substitution in the treatment of epilepsy: case evidence of breakthrough seizures. Neurology. 2008;71:525–30.

Kwan P, Palmini A. Association between switching antiepileptic drug products and healthcare utilization: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;73:166–72.

Kesselheim AS, Bykov K, Gagne JJ, et al. Switching generic antiepileptic drug manufacturer not linked to seizures: a case-crossover study. Neurology. 2016;87:1796–801.

Henschke C, Sundmacher L, Busse R. Structural changes in the German pharmaceutical market: price setting mechanisms based on the early benefit evaluation. Health Policy. 2013;109:263–9.

Kaier K, Fetzer S. The German Pharmaceutical Market Reorganization Act (AMNOG) from an economic point of view. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:291–7.

Strzelczyk A, Schubert-Bast S, Reese JP, et al. Evaluation of health-care utilization in patients with Dravet syndrome and on adjunctive treatment with stiripentol and clobazam. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;34:86–91.

Strzelczyk A, Kalski M, Bast T, et al. Burden-of-illness and cost-driving factors in Dravet syndrome patients and carers: a prospective, multicenter study from Germany. Eur J Paediatr Neurol EJPN. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.02.014.

Schubert-Bast S, Rosenow F, Klein KM, et al. The role of mTOR inhibitors in preventing epileptogenesis in patients with TSC: current evidence and future perspectives. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;91:94–8.

French JA, Lawson JA, Yapici Z, et al. Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2016;388:2153–63.

Rosenow F, van Alphen N, Becker A, et al. Personalized translational epilepsy research—novel approaches and future perspectives: part I: clinical and network analysis approaches. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;76:13–8.

Bauer S, van Alphen N, Becker A, et al. Personalized translational epilepsy research—novel approaches and future perspectives: part II: experimental and translational approaches. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;76:7–12.

Noda AH, Reese JP, Berkenfeld R, et al. Leitlinienumsetzung und Kosten bei neudiagnostizierter Epilepsie. Zeitschrift für Epileptologie. 2015;28:304–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LMW developed the idea for this study. LMW and AS conceived the paper, collected the data, and performed statistical analysis. LMW, JPR, and AS interpreted the statistical analysis and results. LMW and AS created the charts and figures. All authors wrote the paper, discussed the results, contributed to the final manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Study funding

This study was supported by the LOEWE Grant for the “Center for Personalized Translational Epilepsy Research (CePTER), Goethe-University Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Conflict of interest

LM. Willems and J.P. Reese report no conflicts of interest. H.M. Hamer has served on the scientific advisory board of Cerbomed, Desitin, Eisai, GW, Novartis, and UCB Pharma. He served on the speakers’ bureau of or received unrestricted grants from Amgen, Ad-Tech, Bial, Bracco, Cyberonics, Desitin, Eisai, Hexal, Nihon Kohden, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. S. Knake reports honoraria for speaking engagements from Desitin and UCB as well as educational grants from AD Tech, Desitin Arzneimittel, Eisai, GW, Medtronic, Novartis, Siemens and UCB. F. Rosenow reports personal fees from Eisai, grants and personal fees from UCB, grants and personal fees from Desitin Pharma, personal fees and others from Novartis, personal fees from Medronic, personal fees from Cerbomed, personal fees from ViroPharma and Shire, grants from the European Union, and grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. A. Strzelczyk reports personal fees and grants from Desitin Arzneimittel, Eisai, GW Pharma, LivaNova, Medtronic, Sage Therapeutics, UCB Pharma, and Zogenix. All authors confirm that they have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willems, L.M., Hamer, H.M., Knake, S. et al. General Trends in Prices and Prescription Patterns of Anticonvulsants in Germany between 2000 and 2017: Analysis of National and Cohort-Based Data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 17, 707–722 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00487-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00487-2