Abstract

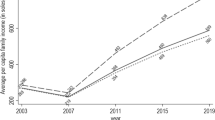

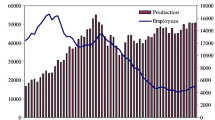

This paper studies the effects of mining intensity and presence on Peru’s mining districts’ welfare from 2004 to 2019. A pooled cross-section regression is used which is constructed from different sources and two sets of comparisons are made: the first compare districts with and without mining presence within mining provinces, and the second compares districts with and without mining presence without the constraint of being within mining provinces. The primary dependent variables included in the model are income inequality, labor income, and poverty rate. In mining districts, inequality has increased, but labor income has increased, and poverty has decreased compared to non-mining districts. However, once control for province-fixed effects and clustered by standard errors at the district level, the significance of inequality is lost, while the impacts on labor income and poverty remain. The transmission mechanisms are human capital, employment, and redistributive policies. Also the mining presence has had positive effects on labor income in other sectors such as construction and commerce; Finally, the labor incomes of unskilled workers increases but not the labor incomes of skilled workers, and it has negatively impacted informal employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data availability on reasonable request.

References

Addison T, Boly A, Mveyange A (2017) The impact of mining on spatial inequality: recent evidence from Africa. WIDER Working Paper.https://doi.org/10.35188/unu-wider/2017/237-3

Agüero JM, Balcázar CF, Maldonado S, Ñopo H (2021) The value of redistribution: natural resources and the formation of human capital under weak institutions. J Dev Econ 148:102581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102581

Alexeev M, Conrad R (2009) The elusive curse of oil. Rev Econ Stat 91(3):586–598. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.3.586

Aragón FM, Rud JP (2013) Natural resources and local communities: evidence from a peruvian gold mine. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(2):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.5.2.1

Aragón FM, Rud JP (2015) Polluting industries and agricultural productivity: evidence from mining in Ghana. Econ J 126(597):1980–2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12244

Barrantes R, Zarate P, Durand A (2005) Te quiero, pero no: minería, desarrollo y poblaciones locales. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos and Oxfam America. India

Beny LN, Cook LD (2009) Metals or management? Explaining Africa’s recent economic growth performance. Am Econ Rev 99(2):268–274

Black D, McKinnish T, Sanders S (2005) The economic impact of the coal boom and bust. Econ J 115(503):449–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.00996.x

Brunnschweiler CN, Bulte EH (2008) The resource curse revisited and revised: a tale of paradoxes and red herrings. J Environ Econ Manag 55(3):248–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2007.08.004

Caselli F, Michaels G (2013) Do oil windfalls improve living standards? Evidence from Brazil. Am Econ J Appl Econ 5(1):208–238. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.5.1.208

Chavez C (2022) The effects of mining presence on inequality, labor income, and poverty: evidence from Peru. Researchgate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360555315_The_Effects_of_Mining_Presence_on_Inequality_Labor income_and_Poverty_Evidence_from_Peru

Chuhan-Pole P, Dabalen AL, Land BC, Lewin M, Sanoh A, Smith G, Tolonen A (2017) Does mining reduce agricultural growth?: Evidence from large-scale gold mining in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, and Tanzania. Mining in Africa: Are Local Communities Better Off?, 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0819-7_ch5

Defensoria del Pueblo (2022) Reporte de Conflictos Sociales. https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Reporte-Mensual-de-Conflictos-Sociales-N%C2%B0-217-Marzo-2022.pdf.pdf

Loayza N, Rigolini J (2016) The local impact of mining on poverty and inequality: evidence from the commodity boom in Peru. World Dev 84:219–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.005

Manzano O, Gutiérrez JD (2019) The subnational resource curse: theory and evidence. Ext Ind Soc 6(2):261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.010

Mavrotas G, Murshed SM, Torres S (2011) Natural resource dependence and economic performance in the 1970–2000 period. Rev Dev Econ 15(1):124–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2010.00597.x

McMahon G, Remy F (2001) Large mines and the community : socioeconomic and environmental effects in Latin America, Canada and Spain. Washington, DC: World Bank and the International Development Research Centre. © International Development Research Centre. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/15247

Mehlum H, Moene K, Torvik R (2006) Institutions and the resource curse. Econ J 116(508):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01045.x

Michaels G (2010) The long term consequences of resource-based specialisation. Econ J 121(551):31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02402.x

Minem (2021) https://www.minem.gob.pe/minem/archivos/file/Mineria/PUBLICACIONES/VARIABLES/2021/BEM%2003-2021(1).pdf

Ministerio de Energía y Minas (2021) Anuario Minero, Reporte Estadistico. https://www.minem.gob.pe/minem/archivos/file/Mineria/PUBLICACIONES/ANUARIOS/2021/AM2021.pdf

Orihuela JC, Gamarra-Echenique V (2019) Fading local effects: boom and bust evidence from a Peruvian gold mine. Environ Dev Econ 25(2):182–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355770x19000330

Sala-i-Martin X, Subramanian A (2012) Addressing the natural resource curse: an illustration from Nigeria. J Afr Econ 22(4):570–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejs033

Ticci E, Escobal J (2014) Extractive industries and local development in the Peruvian Highlands. Environ Dev Econ 20(1):101–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355770x13000685

van der Ploeg F (2011) Natural resources: curse or blessing? J Econ Lit 49(2):366–420. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.2.366

Yamarak L, Parton KA (2021) Impacts of mining projects in Papua New Guinea on livelihoods and poverty in indigenous mining communities. Miner Econ 36(1):13–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-021-00284-1

Yelpaala K, Ali SH (2005) Multiple scales of diamond mining in Akwatia, Ghana: addressing environmental and human development impact. Resour Policy 30(3):145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2005.08.001

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Carlos Chavez wrote the paper and did the analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A

Consent for publication

The author gives consent for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A preprint has previously been published at Chavez (2022), see (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360555315_The_Effects_of_Mining_Presence_on_Inequality_Laborincome_and_Poverty_Evidence_from_Peru).

Appendices

Appendix 1

Tables 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20

National Institute of Statistics, Thomson Reuters and Ministry of Mining and Energy, and author’s calculations. Table 13 shows the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables by first comparison group.

Appendix 2

In this appendix, I show the results of the effects of the presence of mining companies on the level of education:

where \({EDUC}_{i,j,t}\) is the labor income vector that considers people who have attained secondary education or less, and the second one considers people who have attained technical higher education or more. \({Mining}_{j,t}\) is the vector containing the measures of presence and intensity of mines, \({X}_{i,j,t,h}\) is the vector of socioeconomic characteristics of person h in district i within province j in period t. \({Price}_{t}\) is the vector of mineral prices over time t, \({GDP}_{i,j,t}\) is the GDP of district i within province j for period t. \({Canon}_{j,t}\) is the canon received by district i in province j in period t. \(\Gamma\) are the fixed effects of the provinces and \({e}_{j,t}\) are the clustered standard errors at the district level. Table 15 presents the results considering the first comparison group.

The results in Table 16 show that the mining presence has increased the demand for high school education or less, because the earnings of unskilled workers have increased while the earnings of skilled workers have not been impacted. Table 16 presents the results for the second comparison group.

The results in Table 16 show that the mining presence has increased the demand for secondary education or less, because the labor income of unskilled workers has increased while the labor income of skilled workers has not been impacted. These results are in line with the literature that points out and finds that the presence of resource abundance decelerates the accumulation of education, because local communities prefer to specialize in activities related to the natural resource being extracted, these results are in line with those found by Michaels (2010) for the case of coal in the United States. Aragón and Rud (2013) for the specific case of Yanacocha in Cajamarca, unskilled workers saw their real labor income increase while there was no significant change in the real labor income of skilled workers.

Appendix 3

In this appendix, I show the results of the effects of the presence of mining companies on labor income across sectors, using econometrics as follows:

where \({income}_{a,i,j,t,h}\) is the labor income of person h working in sector a of district i within province j in period t. \({Mining}_{j,t}\) is the vector containing the measures of presence and intensity of mines. \({X}_{i,j,t,h}\) is the vector of socioeconomic characteristics of person h in district i within province j in period t. \({Price}_{t}\) is the vector of mineral prices over time t. \({GDP}_{i,j,t}\) is the GDP of district i within province j in period t. \({Canon}_{j,t}\) is the canon received by district i in province j in period t. \(\Gamma\) are the province fixed effects and \({e}_{j,t}\) are the clustered standard errors at the district level. Table 17 presents the results for the first comparison group.

The results in Table 17 show that neither agriculture nor manufacturing revenues have been affected by the mining presence. On the other hand, other sectors such as Construction and Commerce have seen their revenues increase due to the mining presence. Table 18 presents the results considering the second comparison Group.

The results in Table 18 confirm those found in Table 18. The mining presence has positively impacted two sectors, which are Construction and Commerce. These results would support the hypothesis of Loayza and Rigolini(2016) and the findings found by Aragón and Rud (2013), the first paper points out that the mining presence could positively impact the local economy through investments made in that locality, these investments are mainly in infrastructure, on the other hand the second paper finds that the presence of Yanacocha boosted local trade through the purchase of locally produced inputs which boosted the increase of both nominal and real labor income. Like Aragón and Rud (2013) I find no evidence that the mining presence has increased labor income in the agricultural sector.

Appendix 4

This appendix estimates the effects of the presence of mining companies on formal and informal employment labor income, this variable has not been included in the model of the main results because it only has data availability from 2011 onwards, while the main results consider the period 2004– 2019. For this I use the following econometric specification:

where \({Sector}_{a,i,j,t,h}\) is the labor income of person h working in the informal or informal sector in the of district i within province j in period t. \({Mining}_{j,t}\) is the vector containing the measures of presence and intensity of mines, \({X}_{i,j,t,h}\) is the vector of socioeconomic characteristics of person h in district i within province j in period t. \({Price}_{t}\) is the vector of mineral prices over time t, \({GDP}_{i,j,t}\) s the GDP of district i within province j in period t. \({Canon}_{j,t}\) is the canon received by district i in province j in period t. \(\Gamma\) are the province fixed effects and \({e}_{j,t}\) are the clustered standard errors at the district level. Table 19 presents the results for the first comparison group.

The results in Table 19 show that the mining presence has had no effect on either formal or informal employment labor income. On the other hand, I found that the district GDP had negative effects on formal and informal employment labor income. And the mining canon had positive effects on the labor income of informal employment. However, I found that the mining presence had negative effects on informal employment. Table 20 presents the results considering the second comparison group.

The results in Table 20 validate those found in Table 19. The mining presence had no effect on formal and informal employment labor income, but it did reduce informal employment in the mining districts.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chavez, C. The effects of mining presence on inequality, labor income, and poverty: evidence from Peru. Miner Econ 36, 615–642 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00370-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00370-6