Abstract

Chemokines influence HIV neuropathogenesis by affecting the HIV life cycle, trafficking of macrophages into the nervous system, glial activation, and neuronal signaling and repair processes; however, knowledge of their relationship to in vivo measures of cerebral injury is limited. The primary objective of this study was to determine the relationship between a panel of chemokines in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and cerebral metabolites measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in a cohort of HIV-infected individuals. One hundred seventy-one stored CSF specimens were assayed from HIV-infected individuals who were enrolled in two ACTG studies that evaluated the relationship between neuropsychological performance and cerebral metabolites. Concentrations of six chemokines (fractalkine, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1β, and SDF-1) were measured and compared with cerebral metabolites individually and as composite neuronal, basal ganglia, and inflammatory patterns. IP-10 and MCP-1 were the chemokines most strongly associated with individual cerebral metabolites. Specifically, (1) higher IP-10 levels correlated with lower N-acetyl aspartate (NAA)/creatine (Cr) ratios in the frontal white matter and higher MI/Cr ratios in all three brain regions considered and (2) higher MCP-1 levels correlated with lower NAA/Cr ratios in frontal white matter and the parietal cortex. IP-10, MCP-1, and IL-8 had the strongest associations with patterns of cerebral metabolites. In particular, higher levels of IP-10 correlated with lower neuronal pattern scores and higher basal ganglia and inflammatory pattern scores, the same pattern which has been associated with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Subgroup analysis indicated that the effects of IP-10 and IL-8 were influenced by effective antiretroviral therapy and that memantine treatment may mitigate the neuronal effects of IP-10. This study supports the role of chemokines in HAND and the validity of MRS as an assessment tool. In particular, the findings identify relationships between the immune response—particularly an interferon-inducible chemokine, IP-10—and cerebral metabolites and suggest that antiretroviral therapy and memantine modify the impact of the immune response on neurons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chemokines are multifunctional, immunomodulatory proteins that influence HIV neuropathogenesis by multiple mechanisms. First, chemokines can modify HIV replication (Lane et al. 2003) and disease progression (Gonzalez et al. 2005) because HIV uses their receptors to enter cells (Alkhatib et al. 1996; Deng et al. 1996; Dragic et al. 1996; Feng et al. 1996). Second, chemokines can affect macrophage activation (Kaul et al. 2005) and trafficking across the blood–brain barrier (Weiss et al. 1999). Once in the nervous system, HIV-infected macrophages can produce intact virions and inflammatory neurotoxins (Gonzalez-Scarano and Martin-Garcia 2005). Third, since most neural cells express chemokine receptors (Bajetto et al. 2001; Gabuzda et al. 1998), chemokines can affect neuronal signaling and repair in the brain, leading to aberrations in glial and neuronal functions. The evidence supporting these functions derives from multiple sources, including cell culture experiments (Eugenin et al. 2003; Zheng et al. 2001), human and animal studies of chemokine expression in body fluids (Kelder et al. 1998; Zink et al. 2001; Andersson et al. 1998; Letendre 2005; Sevigny et al. 2004) and brain tissue (Sanders et al. 1998; Sui et al. 2003), and population studies of chemokine-encoding genes (Gonzalez et al. 2002; Letendre et al. 2004).

Most of the studies that have evaluated chemokines in vivo have compared their concentrations to either clinical dementia staging or performance on neuropsychological (NP) testing. These studies have provided important insights but have limitations since they may be affected by factors such as the effort of the subject, the composition of the testing battery, or the expertise of the assessor. Subjects who have abnormal clinical staging or NP performance seem to have elevated levels of several chemokines, but this finding does not demonstrate whether each protein is functioning in a predominantly neurotoxic, neuroprotective, or bystander role. Imaging methodologies, such as proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), may address these limitations.

MRS is a sensitive, reliable in vivo method that detects changes in specific cerebral metabolites, which reflect disturbances in cellular function. MRS can measure several cerebral metabolites, including (1) N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), which reflects neuronal injury or loss, (2) choline (Cho), which reflects membrane remodeling, (3) myoinositol (MI), which reflects osmolar shifts and astroglial proliferation, and (4) creatine (Cr), which reflects cellular metabolism. HIV-associated brain injury is characterized by decreased NAA/Cr ratios in white matter and increased Cho/Cr and MI/Cr ratios in white matter and basal ganglia (Lee et al. 2003). Using MRS, our group identified three cerebral metabolite patterns that were associated with the risk of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND): a neuronal pattern that was associated with a threefold increased risk, a basal ganglia pattern that was associated with a twofold increased risk, and an inflammatory pattern that was weakly associated with HAND (Yiannoutsos et al. 2004).

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the relationships between chemokine concentrations in CSF and cerebral metabolites measured by MRS. We hypothesized that chemokine concentrations would be associated with the same pattern of cerebral metabolites that is associated with HAND (i.e., lower neuronal pattern scores, higher basal ganglia pattern scores, and higher inflammation pattern scores). We predicted that chemokines would differ in their associations with cerebral metabolite patterns and postulated that those which most closely reflected the pattern associated with HAND may most strongly influence HIV neuropathogenesis. To address these objectives, we selected six chemokines [monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, interferon-inducible protein (IP)-10, fractalkine (FKN), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, stromal derived factor (SDF)-1, and interleukin (IL)-8] that have been implicated in HAND but differ by the types of cells that produce them, the types of receptors they bind, and the types of cells they attract.

Methods

Subject cohort

Demographic and disease-related data were obtained from AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) protocol 700, which evaluated the relationship between neurocognitive impairment and cerebral metabolites, as measured by MRS. This protocol provided a single MRS assessment from a group of HIV-infected, neurologically unimpaired subjects, and two repeated MRS evaluations from a group of neurologically impaired individuals enrolled in another ACTG study, protocol 301, a randomized, placebo-controlled 16-week clinical trial of memantine for HAND. This latter subject group had repeated MRS evaluations at visit week 0 (prior to initiation of study drug or placebo) and after 16 weeks of study drug or placebo. In all, there were 129 patients providing data for this study: 30 HIV-infected, neurologically asymptomatic controls and 99 ACTG 301 co-enrolled subjects (48 randomized to the placebo group and 51 to the memantine group; Table 1). The local Institutional Review Boards approved the studies at all participating sites. All subjects or their legal guardians gave informed consent prior to screening and enrollment.

Participant assessments

HAND was assessed using the AIDS dementia complex (ADC) staging approach according to the guidelines published by Price and Brew (Price et al. 1991). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy measured four cerebral metabolites (NAA, Cho, MI, and Cr) in three regions of interest (parietal cortex, white matter, and basal ganglia). For the purposes of analysis, NAA, Cho, and MI levels were normalized to creatine levels (i.e., NAA/Cr, Cho/Cr, and MI/Cr ratios were calculated). Composite neuronal, basal ganglia, and inflammatory pattern variables were calculated according to the method of Yiannoutsos et al. (Yiannoutsos et al. 2004):

Participants who were eligible for this analysis had consented to and successfully undergone lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens were stored at −70°C until they were assayed for six chemokines (FKN, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1β, and SDF-1) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Concentrations were adjusted for dilution and for the sensitivities of the assays, which were 30 (FKN), 10 (IL-8), 7.8 (IP-10), 62 (MCP-1), 94 (MIP-1β), and 18 (SDF-1), all expressed in picograms per milliliter. The volume of the 171 stored CSF samples varied from 200 μL to more than 1 mL so the number of chemokines assayed in each sample was determined by a priori prioritization. As a result, the number of concentration values ranged from 53 to 171 across the different chemokines (summarized in Table 2). Assay operators were blinded to other study results.

After assay completion, data were combined with demographic data, clinical staging, other disease-related markers, cerebral metabolites, and treatment arm (when applicable). The other disease-related markers included HIV RNA levels, which were measured by RT-PCR in plasma and CSF (Roche, Amplicor, nominal limit of detection 50 copies/mL), and CD4+ lymphocyte counts, which were measured by flow cytometry. The distribution of MIP-1β concentrations was undetectable in 92% of specimens, so it was eliminated from all analyses.

Statistical analyses

All results were considered statistically significant at the 5% alpha level. No adjustment was performed to account for multiple comparisons when, for example, up to 45 correlation coefficients were calculated (three cerebral metabolite ratios multiplied by three regions of interest multiplied by five chemokines) so these results should be interpreted as hypothesis generating. When estimating correlations between measures which were collected repeatedly (at baseline and week 16), we accounted for the within-subject correlation by using the per-subject mean of each measure and estimating the correlation between the means of the measures rather than the measures themselves. As some subjects had two and some only had one observation, we followed the recommendation by Bland and Altman (Bland and Altman 1995) and weighted the correlation analysis by the number of available measures on each subject. A repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to compare chemokine levels between subjects with early versus late ADC stage while accounting for the correlation of measurements obtained repeatedly within the same subject.

Results

Subject characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and disease characteristics of the 129 subjects included in the analysis. Subjects were mostly middle-aged, white men. Antiretroviral use was common in the cohort, resulting in low HIV RNA levels in most subjects. Most subjects exhibited at least a mild degree of neurological impairment (77%).

Chemokine concentrations

Table 2 summarizes chemokine concentrations in CSF. Almost all the measured chemokines were within the detectable range in the majority of specimens. The principal exception was MIP-1β, which was undetectable in nearly all (92%) specimens. As a result, MIP-1β concentrations were not included in subsequent analyses.

Relationships between chemokines and either clinical ADC stage or individual cerebral metabolites

Higher levels of FKN were associated with worse clinical ADC stage after accounting for the repeated nature of the data at weeks 0 and 16 (p < 0.001). Using a Box–Cox (logarithmic) transformation on the original FKN levels and after the repeated-measures adjustment, the estimated mean CSF FKN level was108 pg/mL (ADC stage ≥2) versus 34 pg/mL (ADC stage ≤1; Fig. 1). No other chemokine was significantly different between mild and more severe ADC patients.

Comparing chemokine concentrations to cerebral metabolites, higher IL-8 levels correlated with higher MI/Cr levels in the parietal cortex (Spearman r = 0.43; p = 0.019). IP-10 levels correlated with lower NAA/Cr ratios in the frontal white matter (r = −0.43, p = 0.003) and higher MI/Cr ratios in the basal ganglia (r = 0.36; p = 0.038) and the parietal cortex (r = 0.44, p < 0.003). Higher MCP-1 levels were associated with lower NAA/Cr ratios in frontal white matter (r = −0.27, p = 0.023) and in the parietal cortex (r = −0.32, p = 0.006). These results are summarized in Table 3. Levels of chemokines, which were associated with cerebral metabolites at a significance level between 5% and 10%, are also shown.

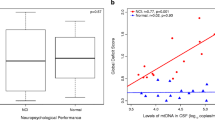

Relationships between chemokines and patterns of cerebral metabolites

Figure 2 summarizes the results of the analyses of chemokines and cerebral metabolite patterns. This analysis demonstrated that higher levels of either IP-10 (r = −0.41, p = 0.006) or MCP-1 (r = −0.31, p = 0.008) were inversely correlated with the neuronal metabolite pattern and IL-8 levels were positively correlated with the inflammatory factor pattern (r = 0.42, p = 0.045).

To account for the use of medications that might confound the relationships between chemokines and cerebral metabolites, we performed two subgroup analyses. First, to account for the potentially confounding effect of antiretroviral therapy (ART), we limited the analysis to only those subjects who were taking no or failing ART, as evidenced by having detectable HIV RNA levels in plasma. In this subgroup, IL-8 no longer correlated with the inflammatory pattern scores, MCP-1 no longer correlated with the neuronal pattern score, and the relationship between IP-10 levels and the neuronal pattern score was attenuated (r = −0.29; p = 0.13). Together, these weakened associations in individuals with detectable HIV RNA levels suggest that ART influences the relationships between chemokines and cerebral metabolites.

Next, to account for the potentially confounding effects of memantine, we repeated our analysis in the subgroup of subjects who were not taking memantine. In this subgroup analysis, the correlation between IL-8 and the inflammatory factor score appeared to be maintained (r = 0.50, p = 0.11) while the correlation between IP-10 and the neuronal factor score appeared to strengthen (r = −0.66; p = 0.001), indicating that memantine use may mitigate IP-10-associated neuronal injury. The correlation between MCP-1 and the neuronal pattern score did not meet statistical significance in this subgroup or the complementary subgroup of individuals who took memantine.

Discussion

Our observations support several hypotheses about the predominant in vivo effects of the study’s targeted chemokines. Specifically, our analyses support that IP-10 and MCP-1 are predominantly neurotoxic because they were associated with evidence of neuronal loss (evidenced by their negative correlations with NAA/Cr ratios and IP-10’s correlation with neuronal factor scores). On the other hand, the role of FKN is less clear as FKN levels were associated with more severe ADC and with MRS evidence of inflammation, but not with MRS evidence of neuronal injury or loss. IL-8 levels were also associated with inflammation, as evidenced by positive correlations with inflammatory factor scores and MI/Cr ratios, but also had no evidence of association with factors of neuronal loss. SDF-1 was not associated with individual metabolites or patterns of cerebral metabolites, and MIP-1β was below detection in too great a proportion of subjects in this heavily treated cohort to reliably assess its association with cerebral metabolites.

Particularly noteworthy was the finding that IP-10 was associated with the same pattern of cerebral metabolites found in individuals with HAND, implicating interferon pathways in HIV neuropathogenesis. In the brain, IP-10, or CXCL10, is expressed by astrocytes and microglia and can attract T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages (Taub et al. 1993). Its expression can be induced by type I or type II interferons (Neville et al. 1997), gp120 (Asensio et al. 2001), or tat (Kutsch et al. 2000). Its receptor, CXCR3, is expressed on neurons but is not a primary co-receptor for HIV cell entry. While some evidence supports that IP-10 may be neuroprotective (Narumi et al. 2002), the preponderance of published data support its neurotoxic properties. For example, IP-10 can stimulate HIV replication (Lane et al. 2003), is associated with accumulation of activated T cells in the CNS (Kolb et al. 1999), is markedly upregulated in brains of macaques with SHIV encephalitis (Sui et al. 2003), and is elevated in the CSF of subjects with HIV-associated neurologic disorders (Kolb et al. 1999). The findings for this interferon-inducible protein are consistent with the transgenic mouse models which have implicated type I interferons in HIV neuropathogenesis (Campbell et al. 1999).

The association between FKN and more severe ADC but only with MI/Cr ratios raises questions about the mechanisms by which FKN might influence neurocognitive functioning. In vitro data have identified that astrocytes can produce FKN during chronic inflammation (Erichsen et al. 2003). While FKN can also result in acute neuronal injury in vitro, the absence of associations with NAA/Cr ratios or neuronal factor scores in the current project suggests that FKN may adversely affect neurons by a mechanism that does not result in their loss.

Our findings stand in contrast to many prior in vivo studies of chemokines in HIV neuropathogenesis, which compared chemokine concentrations to either clinical dementia stage or neuropsychological performance. The findings of Chang et al. stand as an exception, identifying a relationship between a single chemokine, MCP-1, and individual cerebral metabolites (Chang et al. 2004). Our findings are consistent with and extend these findings by identifying relationships between cerebral metabolite patterns and three additional chemokines. Recent studies have also identified that antiretroviral therapy may confound the relationships between chemokines and HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (Sevigny et al. 2004), a conclusion supported by our findings as well.

Our study supports several additional hypotheses. One is that MRS may be a more sensitive outcome measure in studies of HAND than clinical staging. In our analyses, worse ADC stage was associated with higher levels of one chemokine (FKN), but MRS identified three additional chemokines as possibly involved in HIV neuropathogenesis. Another clinically relevant hypothesis is that chemokines are differentially affected by successful antiretroviral therapy. MIP-1β was rarely detectable in this highly treated cohort, but two neurotoxic chemokines, IP-10 and MCP-1, were detectable in almost all specimens assayed. These findings support that some, but not all, chemokines may still have important predictive ability in treated individuals, which is consistent with the findings of Gisolf et al. (2000) and Sevigny et al. (2004).

This study has important limitations that could affect interpretation of its findings. Most importantly, the large number of statistical comparisons, which were not adjusted for this study, implies that some statistically significant results may have been erroneously detected (i.e., false positive results). For this reason, this study should be viewed as a hypothesis-generating investigation, which must be replicated in a larger patient cohort. In addition, this was a post hoc analysis. Since these analyses were not planned contemporaneously with the parent studies, this substudy suffered from incomplete availability of stored specimens, which in turn led to imbalances in measurements across chemokines and resulted in small sample sizes in some analyses. Consequently, the power to detect associations with cerebral metabolites probably differed between chemokines: those that were measured in a larger number of specimens (e.g., MCP-1) likely had greater power to detect an association than those that were measured in a smaller number of specimens (e.g., FKN). The fact that our analyses implicated two chemokines that were not measured in the largest number of specimens (IP-10 and FKN) as being possibly involved in HIV neuropathogenesis suggests that this issue did not severely limit our ability to extract useful conclusions from these data. Finally, the use of antiretrovirals and adjuvant neurological treatment may have also influenced our results. Antiretroviral use was very common and, by design, half of the subjects in ACTG 301 took the NMDA receptor antagonist, memantine. We attempted to limit the potentially confounding effects of these medications by performing subgroup analyses. Overall, the results of the subgroup analyses suggested that ART and memantine influenced the associations between chemokines and MRS findings. Attenuations of the correlations between chemokines and cerebral metabolite patterns may have resulted from the reduced power of the subgroup analyses relative to analyses of the entire group.

We conclude that the comparison of chemokine concentrations to in vivo cerebral metabolite measurements can provide important validation of in vitro findings by enabling inferences about the biological balance of the multiple effects of chemokines in chronically HIV-infected, antiretroviral-treated individuals. Overall, our findings support neurotoxic roles for MCP-1, IP-10, and FKN in HIV neuropathogenesis. In particular, we conclude that interferon pathways, as reflected by the interferon-inducible protein, IP-10, may particularly influence HIV neuropathogenesis.

References

Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM et al (1996) CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272(5270):1955–1958

Andersson J, Fehniger TE, Patterson BK, Pottage J, Agnoli M, Jones P et al (1998) Early reduction of immune activation in lymphoid tissue following highly active HIV therapy. AIDS 12(11):F123–F129

Asensio VC, Maier J, Milner R, Boztug K, Kincaid C, Moulard M et al (2001) Interferon-independent, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-mediated induction of CXCL10/IP-10 gene expression by astrocytes in vivo and in vitro. J Virol 75(15):7067–7077

Bajetto A, Bonavia R, Barbero S, Florio T, Schettini G (2001) Chemokines and their receptors in the central nervous system. Front Neuroendocrinol 22(3):147–184

Bland JM, Altman DG (1995) Calculating correlation coefficients with repeated observations: part 1—correlation within subjects. BMJ 310(6977):446

Campbell IL, Krucker T, Steffensen S, Akwa Y, Powell HC, Lane T et al (1999) Structural and functional neuropathology in transgenic mice with CNS expression of IFN-alpha. Brain Res 835(1):46–61

Chang L, Ernst T, St Hillaire C, Conant K (2004) Antiretroviral treatment alters relationship between MCP-1 and neurometabolites in HIV patients. Antivir Ther 9(3):431–440

Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M et al (1996) Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381(6584):661–666

Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA et al (1996) HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 381(6584):667–673

Erichsen D, Lopez AL, Peng H, Niemann D, Williams C, Bauer M, Morgello S, Cotter RL, Ryan LA, Ghorpade A, Gendelman HE, Zheng J (2003) Neuronal injury induced fractalkine production: relevance to HIV-1 associated dementia. J Neuroimmunol 138:144–155

Eugenin EA, D’Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW (2003) MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem 85(5):1299–1311

Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA (1996) HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272(5263):872–877

Gabuzda D, He J, Ohagen A, Vallat AV (1998) Chemokine receptors in HIV-1 infection of the central nervous system. Semin Immunol 10(3):203–213

Gisolf EH, van Praag RM, Jurriaans S, Portegies P, Goudsmit J, Danner SA et al (2000) Increasing cerebrospinal fluid chemokine concentrations despite undetectable cerebrospinal fluid HIV RNA in HIV-1-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 25(5):426–433

Gonzalez E, Rovin BH, Sen L, Cooke G, Dhanda R, Mummidi S et al (2002) HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia are influenced by a mutant MCP-1 allele linked to increased monocyte infiltration of tissues and MCP-1 levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(21):13795–13800

Gonzalez E, Kulkarni H, Bolivar H, Mangano A, Sanchez R, Catano G et al (2005) The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility. Science 307(5714):1434–1440

Gonzalez-Scarano F, Martin-Garcia J (2005) The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol 5(1):69–81

Kaul M, Zheng J, Okamoto S, Gendelman HE, Lipton SA (2005) HIV-1 infection and AIDS: consequences for the central nervous system. Cell Death Differ 12(Suppl 1):878–892

Kelder W, McArthur JC, Nance-Sproson T, McClernon D, Griffin DE (1998) Beta-chemokines MCP-1 and RANTES are selectively increased in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol 44(5):831–835

Kolb SA, Sporer B, Lahrtz F, Koedel U, Pfister HW, Fontana A (1999) Identification of a T cell chemotactic factor in the cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-1-infected individuals as interferon-gamma inducible protein 10. J Neuroimmunol 93(1–2):172–181

Kutsch O, Oh J, Nath A, Benveniste EN (2000) Induction of the chemokines interleukin-8 and IP-10 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat in astrocytes. J Virol 74(19):9214–9221

Lane BR, King SR, Bock PJ, Strieter RM, Coffey MJ, Markovitz DM (2003) The C-X-C chemokine IP-10 stimulates HIV-1 replication. Virology 307(1):122–134

Lee PL, Yiannoutsos CT, Ernst T, Chang L, Marra CM, Jarvik JG et al (2003) A multi-center 1H MRS study of the AIDS dementia complex: validation and preliminary analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging 17(6):625–633

Letendre SL (2005) The effects of antiretroviral therapy on viral and non-viral markers in cerebrospinal fluid. In: Gendelman HE, Grant I, Everall IP, Lipton SA, Swindells S (eds) The neurology of AIDS, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 617–627

Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Singh KK, de Almeida S, Zimmerman J, Spector SA et al (2004) The monocyte chemotactic protein-1–2578G allele is associated with elevated MCP-1 concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol 157(1–2):193–196

Narumi S, Kaburaki T, Yoneyama H, Iwamura H, Kobayashi Y, Matsushima K (2002) Neutralization of IFN-inducible protein 10/CXCL10 exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol 32(6):1784–1791

Neville LF, Mathiak G, Bagasra O (1997) The immunobiology of interferon-gamma inducible protein 10 kD (IP-10): a novel, pleiotropic member of the C-X-C chemokine superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 8(3):207–219

Price RW, Sidtis JJ, Brew BJ (1991) AIDS dementia complex and HIV-1 infection: a view from the clinic. Brain Pathol 1(3):155–162

Sanders VJ, Pittman CA, White MG, Wang G, Wiley CA, Achim CL (1998) Chemokines and receptors in HIV encephalitis. AIDS 12(9):1021–1026

Sevigny JJ, Albert SM, McDermott MP, McArthur JC, Sacktor N, Conant K et al (2004) Evaluation of HIV RNA and markers of immune activation as predictors of HIV-associated dementia. Neurology 63(11):2084–2090

Sui Y, Potula R, Pinson D, Adany I, Li Z, Day J et al (2003) Microarray analysis of cytokine and chemokine genes in the brains of macaques with SHIV-encephalitis. J Med Primatol 32(4–5):229–239

Taub DD, Lloyd AR, Conlon K, Wang JM, Ortaldo JR, Harada A et al (1993) Recombinant human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med 177(6):1809–1814

Weiss JM, Nath A, Major EO, Berman JW (1999) HIV-1 Tat induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-mediated monocyte transmigration across a model of the human blood–brain barrier and up-regulates CCR5 expression on human monocytes. J Immunol 163(5):2953–2959

Yiannoutsos CT, Ernst T, Chang L, Lee PL, Richards T, Marra CM et al (2004) Regional patterns of brain metabolites in AIDS dementia complex. Neuroimage 23(3):928–935

Zheng L, Calenoff MA, Dal Canto MC (2001) Astrocytes, not microglia, are the main cells responsible for viral persistence in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection leading to demyelination. J Neuroimmunol 118(2):256–267

Zink MC, Coleman GD, Mankowski JL, Adams RJ, Tarwater PM, Fox K et al (2001) Increased macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 in cerebrospinal fluid precedes and predicts simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Infect Dis 184(8):1015–1021

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AIDS Clinical Trials Group), the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH01779, P30 MH 62512, P30 MH62512), the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R01 NS050621, R01 NS41858), and the Universitywide AIDS Research Program. We also acknowledge the contributions of the research subjects and members of the ACTG 301 and 700 teams.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Letendre, S.L., Zheng, J.C., Kaul, M. et al. Chemokines in cerebrospinal fluid correlate with cerebral metabolite patterns in HIV-infected individuals. J. Neurovirol. 17, 63–69 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-010-0013-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-010-0013-2