Abstract

This study aims to analyse the efficiency of sports clubs belonging to the Academic Federation of University Sports and the influence the organisational structure holds over their performance standards. First, we included 92 clubs that registered points in the University Club. The analysis was carried out using the two-stage data envelopment analysis (DEA) methodology to analyse their efficiency. Second, we analysed how strategy, stakeholder relations and funding issues influence organisational efficiency, through a semi-structured interview with the dually efficient club manager. The results show the relevance of analysing the efficiency of these non-profit and public sport organisations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decade, public and non-profit organisations have received substantial attention from the academic community, especially in terms of the innovation they need to incorporate into their governance (Aulgur, 2016; Bukhari et al., 2014; Laurett & Ferreira, 2018; Speckbacher, 2008; Young, 2011) and the resources and revenues they require to obtain their objectives (Fischer et al., 2011; Froelich, 1999; Hansmann, 1980; Wicker & Breuer, 2011; Wicker et al., 2012; Young, 2011). These resources have long since included support provided by the state and with this source crucial to securing the running of these organisations and enabling them to achieve their missions (Barros et al., 2014; Hall et al., 2003; Lasby & Sperling, 2007; Wicker & Breuer, 2013; Wicker et al., 2012; Young, 2011). However, in keeping with the current social and economic conjuncture, these levels of support have experienced a reduction and challenging these organisations to seek out new forms of gaining resources and revenues to guarantee their own survival and/or sustainability. Given this scenario, there is a need to deepen the management capacities of public and non-profit organisations to continue improving the services provided to citizens and society (Breuer & Wicker, 2007; Cairns et al., 2005; Seo, 2020). To achieve this goal, there is a corresponding requirement to measure the performance standards of this type of organisation given that, in keeping with the prevailing scarcity of resources, it is fundamental they optimise their organisational capacities (Balduck et al., 2015; Ferreira et al., 2021; Misener & Doherty, 2013).

This measuring of organisational performance, coupled with applying the correct analytical techniques and diagnosis tools, has become an important question for managers and researchers (Kasale et al., 2018; Madella et al., 2005). Hence, there is a need to analyse the efficiency of these organisations to ascertain their levels of success regarding the investments and funding they receive (Barros, 2003; Berber et al., 2011; Farrell, 1957; Golden et al., 2012; Hong, 2014; Mikušová, 2015).

The literature identifies data envelopment analysis—DEA—as one method of substantial utility for analysing the efficiency of organisations (Carayannis et al., 2017; Emrouznejad & Yang, 2018; Farrell, 1957; Klevenhusen et al., 2021; Margaritis et al., 2021). There has been recurrent usage of this method for research on the sporting context, fundamentally of professional football clubs (Barros & Douvis, 2009; Barros & Garcia-del-Barrio, 2008; Barros et al., 2009, 2014; Dolles et al., 2012; González-Gómez et al., 2011; Guzmán, 2006; Lázaro et al., 2014; Miragaia et al., 2016; Terrien et al., 2017). However, within the scope of non-profit organisations, analysis of their efficiency and particularly the application of the DEA methods have been far rarer (Golden et al., 2012; Hong, 2014; Liu et al., 2019; Miragaia et al., 2016).

Especially in the sporting context, non-profit organisations play a core role in developing and running physical activities. This organisational typology spans the clubs, associations and federations founded to nurture popular participation in regular sporting activities to improve the prevailing quality of life. Hence, this organisational genre also spans numerous and diverse typologies, making evaluating their performances an extremely difficult and complex task (Aulgur, 2016; Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014). Even while the literature contains studies on the context of sporting federations. Such studies are absent regarding the clubs operating within the framework of university sports federations.

Therefore, the present study aims to analyse the efficiency, at the national and international levels, of the organisational models of Portuguese clubs that are regulated by the state organism entitled FADU—the Academic Federation of University Sport through a two-stage data envelopment analysis (DEA) methodology. Additionally, we attempt to analyse how strategy, stakeholder relations and funding issues influence organisational efficiency, through a semi-structured interview with the dually efficient club managers.

This study makes some practical and theoretical contributions. In terms of the literature, it helps to better understand organisational efficiency, particularly in non-profit organisations. The more detailed knowledge of governance models and how the strategic decision-making process is elaborated in this type of organisation is still little known, and this study has tried to contribute to that direction. On a practical level, this study has shown that this type of organisation is still very dependent on governmental funds. In many cases, the strategy is not yet formal, and its efficiency and sustainability must involve the different stakeholders for a greater commitment to society.

Literature Review

Organisational Capabilities of Non-profit Organisations

Non-profit organisations stand out as an emerging sector endowed with the mission of providing services to communities across the most diverse fields and staging activities to involve the participation of their members (Bukhari et al., 2014; Wicker & Breuer, 2014). However, the financial position of these organisations represents a fundamental factor given their common dependence on revenues and income streams to guarantee the sustainability of their multiple social missions (Froelich, 1999; Young, 2007).

In accordance with their financial resources, there is a need to diversify their income sources as a strategic means of reducing their exposure to risks and countering their resource dependence (Fischer et al., 2011). These sources of income are derived primarily from membership fees, fundraising, private and individual contributions, business donations and sponsorship and government contracts and subsidies (Froelich, 1999; Misener & Doherty, 2009; Wicker & Breuer, 2011; Winand et al., 2012). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that these revenue sources may also derive from particular groups of stakeholders with their contributions perceivable as investments designed to foster the objectives of their own companies/organisations (Ivašković, 2019; Miragaia et al., 2015; Speckbacher, 2008; Young, 2011) and that non-profit organisation decision-makers should leverage as an alternative strategy.

According to Wicker and Breuer (2014), financial performance does not represent a priority for these organisations and hence, drawing on the research of Hansmann (1980), these authors define a non-profit organisation as an organisation prevented from undertaking any distribution of profits to its constituent members, specifically employees, managers or directors. This type of organisation thus mobilises its actions in accordance with advancing the services that make up its mission and that should not exclusively focus on obtaining financial gains (Ferkins et al., 2009).

Within the scope of non-profit organisations, many sport organisations do not hold profit as an objective but rather prioritise obtaining sporting results and the participation of their members (Seippel, 2006; Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014; Winand et al., 2013). Nevertheless, this type of organisation should also consider its capacity for handling financial resources to ensure the ability to improve the quality of its services (Ivašković, 2019; Miragaia et al., 2016; Winand et al., 2012). Non-profit sporting organisations also necessarily require the financial income able to guarantee their own sustainability given that displaying a stable financial position is important to entities playing significant roles in the sporting system, thereby shaping their capability to attain their targets and bring about better management of their resources (Froelich, 1999; Wicker & Breuer, 2014; Winand et al., 2010; Young, 2007). Furthermore, Bayle and Robinson (2007) emphasise how the capacity of organisations to win while maintaining their key resources influences their levels of organisational performance. The concept of organisational capacity emerges in the literature on non-profit organisations as a structure that refers to organisational attributes that support organisational efficiency. Corresponding to the ability of an organisation accomplishes the objectives with the least amount of resources, doing things right (Eisinger, 2002). More recently, Misener and Doherty (2013) define organisational capacity as the means of taking advantage of its internal and external resources within the scope of achieving its objectives. These resources reflect the multiple dimensions of capacity, including human resources, strategic planning, infrastructures, financial resources and inter-organisational relationships. Hall et al. (2003) propose that these dimensions, both in isolation and collectively, contribute towards attaining organisational objectives while defining organisational capacity as incorporating the application of three types of capital: (i) financial, therefore the capacity to develop and deploy financial capital (hence, the revenues, expenses, assets and liabilities of an organisation); (ii) human, reflected in the capacity to gain meaningful returns on the human capital available (hence, paid employees and volunteers) within the organisation and their respective competences, knowledge, attitudes, motivations and behaviours and (iii) structural, thereby spanning the capacity to apply non-financial capital that remains even when members of an organisation move on.

Thus, improving the organisational capacity implies a deeper understanding of the involvement of stakeholders. Within this framework, knowledge about the effective contributions of stakeholders to non-profit sporting organisations provides crucial input to developing sustainable strategies for achieving their missions (Ivašković, 2019; Miragaia et al., 2014, 2016).

Given the above, we may grasp organisational capacity as a multidimensional facet and essential to better coordination between internal and external stakeholders and enabling an understanding and the clarification of the contribution each makes towards the inputs necessary for advancing with the organisational mission (Hall et al., 2003; Hou et al., 2003; Sakires et al., 2009). This perspective highlights how the concept of organisational efficiency interlinks with stakeholders’ contributions (Miragaia et al., 2016).

Measuring Efficiency

Achieving efficiency is vital to every economy sector, and sports are no different (Barros et al., 2014). Sport efficiency is generally subject to analysis in economics and management terms (Barros et al., 2009). In sports organisations, efficiency is more closely associated with the financial means invested to obtain sports-related targets to maintain the financial viability of such organisations. Therefore, sustainable financial management becomes a core condition for ensuring organisational success (Wicker & Breuer, 2014).

Identifying the efficiency performance level of systems today constitutes one of the great challenges to research in the social sciences. This is a major issue given that performances undertaken efficiently are fundamental to the survival and growth of operational systems at every level—individuals, organisations and societies. Various terms have been deployed to identify and describe the concepts underlying the performance of any system, including costs, productivity, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness relationship and especially efficiency (Shaw, 2009).

Madella et al. (2005) state that the general understanding of organisational performance involves a combination of effectiveness and efficiency. This defines effectiveness as an organisation’s capacity to obtain its objectives while efficiency compares the relationship between the resources consumed and the results obtained by an organisation without considering consumer satisfaction. In turn, Farrell (1957) defines efficiency as the difference between that is produced (the outputs) and what is required for the production process (the inputs) for a company to be able to obtain its maximum potential. More recently, Mirfakhr-al-Dini and Khatibi-Aghda (2011) propose the definition of efficiency as the maximum quantity of outputs obtainable based upon the inputs made. From an output-oriented perspective, efficiency becomes the proportion of an organisation’s production for the maximum level of outputs achievable when considering the levels of inputs (Johnes, 2006).

Having established the production point for a company, measuring the efficiency requires estimating the production function to estimate the potential production point then. This estimate may stem from applying various parametric and non-parametric techniques (Farrell, 1957). For example, parametric methods, such as stochastic frontier analysis (SFA),are stochastic and specifically define the production function and generally in terms of cost of the profit function. The non-parametric methods, as is the case with free disposal hull (FDH) and data envelopment analysis (DEA), are deterministic and, generally, ascertain a ratio balancing the amount of inputs against the weighted sum of the outputs, with the DEA approach among those most commonly found in the literature (Mikušová, 2015).

According to Farrell (1957), the data envelopment analysis term conveys a mathematical programme approach to establishing the frontiers of production and measuring the efficiency of the frontiers. The production frontiers are a function of production that seeks to maximise the level of outputs based on a determined level of inputs. Later, Charnes et al. (1978) put forward a model with an input orientation and assumed returns were constant with scale. The input orientation is adopted whenever seeking to minimise the quantity of resources purposefully employed to maintain production (Guzmán & Morrow, 2007), usually in monopolist markets (Barros & Garcia-del-Barrio, 2008). However, the sporting context requires an output focused orientation as this assumes control over the inputs and maximises the outputs while maintaining the consumption of resources as a constant (Barros & Santos, 2003).

The DEA method provides for the usage of multiple inputs and outputs, but neither imposes any functional form on the data nor does it proffer any suppositions about the term of error distribution (Barros & Garcia-del-Barrio, 2008). Despite the relative scarcity of studies on the efficiency of sporting organisations, DEA has come in for greater utilisation (Barros & Douvis, 2009; Falasca & Kros, 2018; Villa & Lozano, 2018; Zelenkov et al., 2017).

Efficiency of University Sports Clubs

The government and sport have long been intrinsically bound together for various political questions (Green & Collins, 2008). To implement sport policies, governments provide financial backing to various sports organisations, including the sports federations, in keeping with their presentation of annual activity programmes (Barros, 2003; Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014). As strategic objectives, the sports federations seek to organise sporting activities and competitions for their members, informing and supporting the athletes and players at the respective affiliated sports clubs (Winand et al., 2013). In accordance with Masoumi et al. (2013), sports federations, based on their objectives, missions and functions, gained a privileged position in the staging of multi-dimensional development programmes.

According to Dietschy (2013), the federations are one of the organisations fundamental to regulating sporting practices under a professional regime, and Wicker and Breuer (2014) propose how a diverse set of sporting associations constitutes an important component of the sporting system. This sporting system takes the structure of a pyramidal system organised into different levels of intervention, especially the international, national and regional, with sports federations responsible for organising and developing sport across every hierarchical level, thus from amateur to professional (Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014). According to Devecioglu et al. (2012) and Lee et al. (2013), sport currently receives recognition as a crucial means of fostering health, culture and as well as education. Popeska et al. (2015) state that for the specific case of higher education, such institutions should provide a complete education, thereby extending beyond conveying pure academic knowledge. They should therefore provide opportunities for the complete and harmonious development of future citizens, making a range of sporting and cultural activities available, among other aspects, to bring about a holistic approach to education.

Furthermore, Devecioglu et al. (2012) acknowledge how sport in a university environment becomes a leading tool for socialisation. Correspondingly, university students participate in sporting activities primarily on motivations inherently interrelated with joy and happiness while also pointing to drivers of an extrinsic nature, such as wishing to stay in shape, control their weight and reduce stress (Kilpatrick et al., 2005), as factors. Within this context, university sports nurture environments that provide sporting incentives to students to strive for excellence in academic and sporting terms and ensure participants’ opportunity to interact socially and competitively (Weiss, 2010). Hence, university sport ensures the opportunity to face more intense challenges that enable the application of potential competences, training new capacities, achieving greater autonomy and participating in more complex and distinct environments (Asri et al., 2014). Popa (2013) states that university sports need to be analysed from the organisational perspective, including the appropriate management of resources. Thus, this same management of resources, especially financial resources, conveys the need for strategic plans tailored to the current complexity of university sport (Gheorghe & Nicolae, 2015). For this set of reasons, university sports organisations also require management professionals, especially with appropriate human resource backgrounds, to draft and implement more efficient organisational strategies (Gheorghe, 2014).

We should also reference how university sports take on various configurations, particularly the opportunity to engage under a recreational and leisure regime and within more competitive circumstances. The competitive facet in the Portuguese context is currently regulated by a public sector federation, FADU—the Academic Federation of University Sports. As a sporting federation, FADU displays a non-profit associative structure of various management entities and remunerated employees working in various areas. The federation operates through a network with various structures and university clubs interconnected with higher education institutions. Through various activities, the objective is to foster student competition, socialisation and exchanges across the most diverse higher education institutions nationally and internationally, providing incentives for a competitive spirit, teams and fair play and fostering the adoption of healthy life styles among the academic community. In overall terms, the FADU mission is to represent higher education sport and sporting interests before the state, other sports federations and the many sports organisms and entities across the higher education system; while also contributing, through sporting practices, to strengthening the academic spirit; fostering, regulating and staging national and international sporting competitions within the scope of higher education; promoting and organising national university teams and fostering the continued improvement in terms of the services provided by university sports organisations.

In keeping with that stated above, we were able to verify how the efficiency of sports organisations has been the target of study by various researchers, especially within the non-profit organisation framework (Barros & Garcia-del-Barrio, 2008; Froelich, 1999; Gheorghe, 2014; Gheorghe & Nicolae, 2015; Masoumi et al., 2013; Miragaia et al., 2016; Popeska et al., 2015; Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014; Speckbacher, 2008; Wicker & Breuer, 2014; Winand et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Young, 2007). However, there is a lack of studies analysing the efficiency of clubs associated with university sports federations. Hence, this study seeks to overcome this shortcoming by analysing the efficiency of the clubs related to FADU by deploying the two-stage data envelopment analysis (DEA) methodology applied at the national and the international levels while also considering the influence that organisational structure may have on obtaining efficiency.

Method

Sample and Date Collection Procedures

The current study involved 92 clubs out of 123 regulated by a public sector organisation entitled FADU—the Portuguese acronym for the Academic Federation of University Sport. The selection of the 92 clubs stemmed from the inclusion criteria stipulating each club had to have picked up at least one point in the TUC–the University Club Trophy over the five seasons analysed (2010/2011 to 2014/2015).

In the first phase, we sourced the data through the three FADU activity reports, particularly as regards the records for (i) the TUC—the University Club Trophy that determines the club with the best performance in all of the official events and competitions organised at the national level; (ii) the Medal table that details the number of gold, silver and bronze medals won by each club in the National University Championships; and as well as (iii) the Participation Control Table for the seasons held between 2010/2011 and 2014/2015, thereby informing on the number of sports the clubs participated in alongside the number of registered athletes, officials and trainers. This excluded 31 clubs because they did not gain any TUC points in any season over this period. This analysis also included each club’s details regarding the team and individual sports competed in by female and male athletes (Table 1).

The second phase analysed those clubs ranked as efficient at the national level to ascertain whether they maintained this efficiency at the international level. This process sought to identify the clubs with the best performance across the two levels.

Subsequently, and intending to identify the management mode underpinning the strategies of efficient club(s), we drafted and applied a semi-structured interview (Arnold et al., 2015; Fletcher & Arnold, 2011) with a manager responsible for the respective club(s). The interview script took into account the recommendations in the literature for improved management of organisational capacity (Froelich, 1999; Hall et al., 2003; Miragaia et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Misener & Doherty, 2013; Speckbacher, 2008; Wicker & Breuer, 2014; Winand et al., 2012; Young, 2007, 2011). Hence, the interviews sought to grasp the organisational structure underlying the results that demonstrate an organisation has attained efficiency.

Data Instrument and Treatment

Analysis of club efficiency took place according to the non-parametric DEA method, developed by Farrell (1957), implemented by the Frontier Analyst® software version 4.2.0 and published by Banxia Software®. The application of DEA requires defining the inputs and outputs with the selection of items appropriate to the respective organisational context crucial to determining whether or not the results hold any practical utility (Hong, 2014). The model adopted considered variable returns to scale (VRS), commonly recognised in the literature as DEA-BBC (Banker et al., 1984) and recommended by Barros (2003). It was also selected an output orientation since this approach maximises outputs by maintaining the same level of inputs. According to the model, a DMU is efficient when it has a score equal to 1. Values below 1 suggest inefficiency, indicating how near it is to the efficiency frontier, enabling decision makers to operate more objectively in specific DMUs.

In this study, we applied the two-stage DEA methodology that, according to the literature, provides a clearer basis for analysing the efficiency of non-profit sectors and enabling the inclusion of a greater variety of inputs and outputs for study (Berber et al., 2011; Golden et al., 2012; Hong, 2014; Simar & Wilson, 2007). Therefore, and given that clubs may obtain national levels of efficiency but fall short of the international level, this approach considers the analysis of the sports context across two distinctive levels to identify whether efficiency/inefficiency enables more objective analysis for subsequently defining a strategic planning process. Considering how university clubs participate and compete not only at the national level but also at the international level, the option for the two-stage DEA methodology returns the added value given that, as Hong (2014) explains, a single input/single output approach may restrict the information provided. Thus, the results only detail some variables’ information without defining their effects on the other variables.

To advance with the analysis of club efficiency through the DEA method, we selected distinct inputs and outputs in accordance with analysing the national or the international efficiency scale (Table 2).

The choice of variables arose from the items available in the FADU database and focuses on indicators for productive activities, as is the case with the number of athletes participating as this reflects one of the central objectives of the Federation’s mission, to boost the numbers of university students participating in sport. While on the one hand, the number of athletes involved represents a fundamental dimension of club activities. Their performance emerges in the points and medals obtained in the national and international championships that correspondingly also reflect an indicator for consideration in management model evaluation processes.

The number of athletes gains widespread recognition as a variable in the literature given its registration throughout the sporting season and serving as a constant factor of production (Barros & Douvis, 2009; Barros & Leach, 2006; Espitia-Escuer & García-Cebrián, 2010; Picazo-Tadeo & González-Gómez, 2010). Nevertheless, this factor gets undermined whenever there is a shortage of athletes and/or their unavailability for participation imposed by the federated club in FADU events.

The number of sports is a crucial variable that requires significant management on behalf of the clubs in keeping with how their division into a different team and individual sports requires clubs to implement different coordinating structures. Team sports involve a larger number of athletes and hence require greater logistics for participation resulting in higher financial costs.

The number of medals won and the weighting of each category (gold, silver or bronze) reflect the success gained by the club and thereby reflecting the investments made (Halkos & Tzeremes, 2013; Valério & Angulo-Meza, 2013; Wu et al., 2013). On attaining such success, new challenges and competitions emerge, especially at the international level (Espitia-Escuer & Garcia-Cebrian, 2008; Haas, 2003; Haas et al., 2004; Kounetas, 2014) in which club participation essentially depends on the support received from the university they represent to meet the costs incurred in registration, transport, board and accommodation.

The TUC–the University Club Trophy emerges as a variable adopted by various research studies into efficiency (Barros & Douvis, 2009; Barros & Garcia-del-Barrio, 2008; Barros & Leach, 2007; Barros et al., 2009, 2014; Espitia-Escuer & Garcia-Cebrian, 2008; Haas, 2003; Haas et al., 2004; Kounetas, 2014), indicating the productivity of the clubs over the season, thus the points obtained in accordance with their productive processes (Espitia-Escuer & Garcia-Cebrian, 2008; Haas, 2003; Haas et al., 2004; Kounetas, 2014).

As regards calculating the efficiency, this applied the average values for each input and output corresponding to the five sports seasons spanning the period between 2010/2011 and 2014/2015 with the particularity that the sports input item and the medals output receive different weightings in accordance with the type of sport (team or individual) and the type of medal (gold, silver or bronze). As regards the types of sports, especially team sports, as these involve a larger number of participants per team than individual sports, tailoring this input was important (Table 3). Regarding the medals, we applied these weightings to reflect the hierarchal value of each medal type and have correspondingly attributed the weighting of 0.5, 0.3 and 0.2 to the gold, silver and bronze medals, respectively.

We subsequently applied the semi-structured interviews with the manager(s) of the efficient club(s) at the international level that spanned the dimensions of organisational strategy, stakeholders and financing (Table 4).

Results

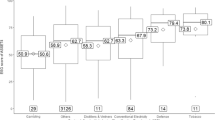

Out of the 123 clubs total, we selected 92 clubs for analysis, keeping with how they had registered at least one TUC point over the five seasons under analysis. This also incorporated consideration of the background of these 92 clubs, with only 76 clubs included for DEA analysis given that the remainder returned no outputs in terms of winning gold, silver and bronze medals at the national level. According to the DEA results, only nine clubs obtained efficiency at the national level. Analysis of the national level efficiency of the 76 clubs studied for the period between 2010/2011 and 2014/2015 features in Table 5.

Furthermore, Table 5 also details how 11 clubs obtained 100% efficiency over the seasons analysed. However, three of these clubs (AEISCAC, AEESAE and ISMAT) return null values for the reference number, with two clubs reporting a deficit in their inputs and outputs (AEESAE and ISMAT). We may also identify how seven clubs present efficiency results of between 80 and 100%. This also observes how the U. Porto and IPVC clubs report reference values of 44 and 43, respectively, identifying them as the clubs applying the resources available in the most efficient fashion. Given that the U. Porto club emerges as the benchmark reference, there is relevance in considering whether its efficiency displays a constant annual trend to grasp this organisation’s profile towards its inputs and outputs. Hence, we analysed this club’s efficiency throughout the five sports seasons (Table 6).

Table 6 duly reports that the U. Porto club presented an efficiency rate of 100% across four seasons, specifically 2010/2011, 2011/2012, 2013/2014 and 2014/2015. However, in the 2012/2013 season, the club obtained an efficiency rating of 74.91% resulting from an excessive number of athletes, and individual sports competed in alongside a shortfall in the number of metals and TUC points obtained.

As regards the analysis of the efficiency at the international level, we may ascertain that of the nine clubs identified by the DEA process as efficient at the national level, only one won medals in international events (U. Porto club) and hence the remainder received a zero result for this variable (Table 7). This fact prevented the analysis of the international efficiency of these clubs through recourse to the DEA method.

Once again, the analysis of the efficiency of the U. Porto club emerges as highly important and thus requiring consideration of whether this club’s behaviour attains this standard of excellence constantly or subject to fluctuations over the different sports seasons (Table 8).

According to Table 8, we may report that U. Porto turned in the best result of the five seasons under analysis at the international level in the 2014/2015 season. This derives from the major progress achieved in both the inputs and outputs, especially in increasing the number of athletes, sports and medals won. Given that in the seasons from 2010/2011 to 2013/2014, the club won only a total of two bronze medals, we may assume that it was in the final season that the club managed to obtain efficiency at the international level and thereby stand out in the universe of university sports clubs.

Hence, and to be able to understand these results better and whether issues related to financing, strategy and/or relationships with stakeholders best explain this success, we carried out a semi-structured interview with the U. Porto club manager. Table 9 details the questions, answers from the club manager and the dimensions to which each question corresponds.

Discussion

Of the 92 clubs analysed for this five-season period, only nine clubs achieved a ranking of efficiency. It is important to understand the variables for which these clubs did not obtain the expected results to understand the measures necessary to correct this situation. These nine clubs do not return deficits across any of the variables, which means that based on the number of inputs, they can maximise the outputs, thus attaining maximum efficiency (Farrell, 1957). Despite only these nine clubs receiving the efficiency classification, two clubs obtained 100% efficiency, thus AEESAE and ISMAT. However, the DEA method did not report these clubs as efficient in keeping with how they shared the need to reduce the percentage number of athletes, 0.37 and 0.6, respectively, a deficit of 1.17 in TUC points at AEESAE and a deficit of 0.04 in the medal total at ISMAT. Of the nine efficient clubs at the national level, only the U. Porto club attained efficiency at the international level.

Hence, following analysis of the club’s strategic plan, we may observe how in this type of organisation, the capacity to manage financial resources also requires consideration to be in a position to undertake investments in improving the quality of the services provided (Miragaia et al., 2016; Winand et al., 2012). However, according to Wicker and Breuer (2014), financial performance does not represent a priority to these organisations and thus, despite the manager referencing financial matters as important (Froelich, 1999; Wicker & Breuer, 2014; Winand et al., 2010; Young, 2007), he also detailed how federation support should concentrate more on the logistical field:

… FADU should not concentrate so much on the support given to the teams going to participate in the championships but rather in terms of the level of organising those championships … support the clubs in their organisation. In a role of helping and organising, through their technical delegations for each sport …

Thus, this highlights how, despite this type of organisation being highly dependent on sources of financing that derive primarily from government subsidies, it remains fundamental to encounter other forms of supporting their development. Furthermore, this does not rule out political responsibility for supporting this type of entity (Barros, 2003; Green & Collins, 2008; Škorić & Bartoluci, 2014; Wicker & Breuer, 2011; Winand et al., 2012).

Such federations play extremely important roles in developing and promoting sport, especially through regulating sporting practices under professional regimes (Dietschy, 2013). They gain privileged positions in multi-dimensional development programmes (Masoumi et al., 2013). FADU, as the sports federation governing university sport at the national level, might be able to meet some of these costs, especially through reducing administrative charges and the price of registration as well as attributing a larger number of grants to clubs organising national championships throughout the sports season (Froelich, 1999; Misener & Doherty, 2009; Wicker & Breuer, 2011; Winand et al., 2012). The U. Porto club manager explained when identifying how the Federation should support “More in terms of the organisation of championships, that is, it should be concerned about supporting the clubs in their organisation”. This support also involves human resources that, according to the CDUP director, are fundamental to qualitatively boosting the championships and being able to economise on the costs to clubs when they participate at the international level:

… this would bring about a qualitative leap as regards the organisations …” and “... FADU should continue, and does so well, to provide support to clubs that participate, especially through human resources to accompany the international competitions given that this would be a way of saving more money for the clubs.

This type of dynamic might attract more higher education institutions to engage in university sport alongside greater investment and potentially the greater efficiency of the clubs themselves (Froelich, 1999; Wicker & Breuer, 2014; Winand et al., 2010; Young, 2007). Within this framework, federation support emerges as a fundamental source of resources for clubs but that requires complementing by capturing the interest of other stakeholders (Miragaia et al., 2015; Speckbacher, 2008; Young, 2011).

Clearly, as with any other type of organisation, non-profit organisations also need to seek the best ways to achieve sustainability, especially through improving their structures and deepening their specialist human resources. This represents the case with the U. Porto club that, after the founding of CDUP, an autonomous structure, encountered the need to recreate a more professional model of organisation and to specialise its human resources across the different departments as advocated by Gheorghe (2014) and outlined here by the CDUP director:

From one moment to the next, we became an autonomous service and managing the University’s sports installations and with this change not accompanied by any human resources that just remained the same. Following this, we had to restructure and set up two departments; one to manage the sports installations and another for the sporting activities that covers both the leisure and competitive sports and now, more recently, we’ve divided up still further and placed the management of the sports and competition facilities in one department and the leisure and fitness facilities in another so that we can have staff allocated to the specific tasks within the structure.

Hence, taking due advantage of the resources available to an organisation interconnects with its organisational capacities as they provide the means for organisations to obtain their objectives (Misener & Doherty, 2013). In the absence of these resources, stakeholders emerge as a good alternative as their support is crucial to ensuring the revenue sources that guarantee the sustainability of sports organisations and enabling them to obtain their goals and better manage their resources in overall terms (Miragaia et al., 2015; Speckbacher, 2008; Young, 2011). Furthermore, these stakeholder ties are also an essential aspect for club managers to take into account when developing sustainable strategies as put forward by other studies (Miragaia et al., 2014, 2016) to the extent of constituting a failure of managers not yet to have integrated other types of stakeholder in their management plans:

It is our failure, as the manager, to have the support of stakeholders in terms of leisure but not in terms of the competition dimension and this increases the costs incurred.

Another facet with implications for club sustainability derives from the number and the competences of its human resource staff. This seems a relevant variable in keeping with how, for this type of organisation, maintaining the same working teams over significant periods is relatively uncommon given that, in the majority of cases, they answer to the higher education institution rectorship and the respective leadership of the academic associations (which vary between periods of 2 and 4 years). This lack of stability impacts directly on the clubs given that they are subject to the different objectives proposed by the various management teams they answer to and potentially reflecting, for example, on support going to different university sports. As the CDUP director stressed in detailing how:

… there is no doubt at all that without the significant investment that the University makes, it would not be feasible to have competition sport because, in reality, our largest cost in the Sports Centre is with competition.

Hence, the results returned display different patterns in terms of efficiency levels. Across the majority of inefficient clubs, the results for the variables registering the inputs (number of athletes and sports) convey a need either to maintain or reduce, which means that for these clubs to achieve efficiency, they need to reduce or maintain the number of athletes and the sports they compete in. However, this scenario apparently falls beyond the scope of university clubs given that they strive to attract and involve athletes to join the club and represent their higher education institution/student association. However, when the clubs encounter an excess of athletes, they engage in a selection process as is the case with the club that reported the highest efficiency level (U. Porto). Despite the contradiction of the mission of this organisational type, this selection system results from the impossibility of clubs maintaining too many athletes in too many sports. This stems from the costs involved and the difficulties inherent in meeting all of the competitive regulations, especially collective sports. This practice is in effect at the U. Porto club as its director referenced when explaining how “we hold selection training sessions and internal activities…” thus conveying the need to filter the athletes and players going onto represent the club.

In turn, the outputs of inefficient clubs at the national level generally portray the need to boost the numbers of medals won alongside the number of TUC points. As a criterion for measuring efficiency, the quantity of medals is a relatively recent application from the research perspective (Espitia-Escuer & Garcia-Cebrian, 2008; Haas, 2003; Haas et al., 2004; Halkos & Tzeremes, 2013; Kounetas, 2014; Valério & Angulo-Meza, 2013; Wu et al., 2013) in which the activities of clubs generate a favourable effect on the winning of medals and ensuring future investment in the club (Halkos & Tzeremes, 2013; Valério & Angulo-Meza, 2013; Wu et al., 2013). This aspect received confirmation in the interview held with the U. Porto club manager who mentioned how:

… we know that it is through winning medals and participating in events that means we are able to gain financing …

Good results in competitions enable the clubs to go onto new challenges and competitions not only at the national level but also at the international level and thereby not only representing the respective club but also the country (Espitia-Escuer & Garcia-Cebrian, 2008; Haas, 2003; Haas et al., 2004; Kounetas, 2014). This should also refer to how in the case of university sport, beyond this type of profile, it raises awareness of a particular higher education institution and its range of educational services beyond national borders. This aspect has today become fundamental as regards the importance attributed to internationalisation. This type of institutional promotion turns higher education entities themselves into stakeholders with which a strong relationship is an essential dimension beyond leasing the spaces and facilities where the sporting practices occur.

However, this winning of medals becomes difficult to achieve given the prevailing conditions of some of these organisations, especially the lack of both quality athletes and technical support teams, shortcomings in training installations and especially due to the high financial costs arising from making improvements to these factors and registering clubs for events, frequently rendering their participation inviable across both the national and international levels (Froelich, 1999; Young, 2007). Through this lack of sustainability and the means to obtain their objective, we can perceive the motives why only nine clubs attain efficiency at the national level and with one efficient in international terms. It thus also becomes difficult for a university club to guarantee its sustainability and becomes efficient when there is resource dependence and a lack of support forthcoming from stakeholders, as in the case of sponsors and the government. According to the CDUP Director, this is a failure belonging to each club’s manager in a trend already identified by various researchers (Miragaia et al., 2015; Speckbacher, 2008; Young, 2011). Furthermore, despite this type of sports organisation being highly dependent on federations and other government support, other forms of assistance reach beyond traditional financial matters, especially strengthening the means available in logistical and organisational support.

Given that set out above, we may highlight how this type of result enables effective decision-making processes in state entities of a non-profit type, especially due to the methodological data and procedures susceptible for deployment in defining organisational strategies. Analysis of the efficiency enables club decision-makers to identify which inputs and outputs may be maintained or altered in keeping with a strategic vision that should align the organisational model and optimise the ongoing relationships with stakeholders.

Conclusion

This study analysed the efficiency of university sports clubs throughout five seasons. The efficiency analysis took place according to the DEA method and identified how, out of a total of 92 clubs, nine achieved efficiency at the national level, with only one club managing to rank as efficient on the international scale.

According to the qualitative analysis made through the semi-structured interview with the club manager efficient across both levels, we were able to identify the existing relationship between the organisational structure adopted by the club and the results in terms of the efficiency levels. This concludes that the type of organisational model underpins this performance, especially the structure in place, the application of specialist human resources, the ongoing relationships maintained with stakeholders and the means of financing in effect.

We may also conclude that this type of organisation remains highly dependent on the sources of income supplied by the government and the respective supervisory organisation (the Federation of University Sports) even while finding alternatives and achieving greater autonomy remain fundamental to guaranteeing the sustainable continuation of these clubs. The definition of a strategic plan should also extend to identifying those stakeholders capable of bringing added value to these organisations.

From the point of view of study limitations, we would reference how the efficiency analysis depends on the inputs and outputs selected, with this aspect duly requiring consideration. Furthermore, this type of study is always dependent on the data available on the entities under study, especially through activity reports; hence, researchers are not always able to obtain all the sought-after data. Thus, as already identified, analysis of university club efficiency represents a field that still needs consolidation in research, particularly focusing on the connections with the different stakeholders. In terms of the scope for future studies, we may thus particularly point to the need to identify which stakeholders hold the greatest influence over the efficiency of this type of sports organisation. This should also not ignore that the choice made over the inputs and outputs incorporated into evaluations of club efficiency requires triangulating with other indicators in future studies, namely clubs’ training grounds and facilities, the managers, the staff, the quality of training and the financial sources other than public funding. Furthermore, this study focused its analysis on the identification of an organisational model of an efficient club, even while it is fundamental for clubs that fail to make this efficiency grade to be subject to this same type of analysis to discern the obstacles that hinder them from obtaining higher levels of efficiency within the framework of an organisational system with its own particular characteristics. One of the variables that may affect efficiency may result from the geographical/spatial location of clubs, as proximity to large urban centers allows access to better managers and athletes than clubs which operate in smaller towns or rural areas. In future research, it will be important to proceed with a qualitative approach to identify the strategic reasons of each club and developing other quantitative approaches (Simar & Wilson, 2007) to understand the impact that each variable has on the others. Furthermore, another possible approach could be the developing studies of longitudinal nature to extend the analysis period.

References

Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Anderson, R. (2015). Leadership and management in elite sport: Factors perceived to influence performance. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(2–3), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.10.2-3.285

Asri, S. Z. S., Akbari, B., & Farahbakhsh, A. (2014). Sport motivation among Iranian University students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 810–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.790

Aulgur, J. J. (2016). Governance and board member identity in an emerging nonprofit organization. Administrative Issues Journal: Education, Practice & Research, 6(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.5929/2016.6.1.1

Balduck, A., Lucidarme, S., Marlier, M., & Willem, A. (2015). Organizational capacity and organizational ambition in nonprofit and voluntary sports clubs. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(5), 2023–2043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9502-x

Banker, R. D., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management Science, 30(9), 1078–1092. https://doi.org/10.1287/MNSC.30.9.1078

Barros, C. P. (2003). Incentive regulation and efficiency in sport organisational training activities. Sport Management Review, 6, 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(03)70052-7

Barros, C. P., & Douvis, J. (2009). Comparative analysis of football efficiency among two small European countries: Portugal and Greece. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 6(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2009.028801

Barros, C. P., & Garcia-del-Barrio, P. (2008). Efficiency measurement of the English football Premier League with a random frontier model. Economic Modelling, 25(5), 994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2008.01.004

Barros, C. P., Garcia-del-Barrio, P., & Leach, S. (2009). Analysing the technical efficiency of the Spanish Football League First Division with a random frontier model. Applied Economics, 41(25), 3239–3247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701765379

Barros, C. P., & Leach, S. (2006). Performance evaluation of the English Premier Football League with data envelopment analysis. Applied Economics, 38(12), 1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500396574

Barros, C. P., & Leach, S. (2007). Technical efficiency in the English Football Association Premier League with a stochastic cost frontier. Applied Economics Letters, 14(10), 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850600592440

Barros, C. P., Peypoch, N., & Tainsky, S. (2014). Cost efficiency of French soccer league teams. Applied Economics, 46(8), 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2013.854304

Barros, C. P., & Santos, A. (2003). Productivity in sports organisational training activities: A DEA study. European Sport Management Quarterly, 3(1), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740308721939

Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2007). A framework for understanding the performance of national governing bodies of sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(3), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701511037

Berber, P., Brockett, P. L., Cooper, W. W., Golden, L. L., & Parker, B. R. (2011). Efficiency in fundraising and distributions to cause-related social profit enterprises. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 45(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2010.07.007

Breuer, C., & Wicker, P. (2007). Sports clubs in Germany. Sport Development Report, 2008, 5–50.

Bukhari, I. S., Jabeen, N., & Jadoon, Z. I. (2014). Governance of third sector organizations in Pakistan: The role of advisory board. South Asian Studies (1026-678X), 29(2), 583–596.

Cairns, B., Harris, M., & Young, P. (2005). Building the capacity of the voluntary nonprofit sector: Challenges of theory and practice. Intl Journal of Public Administration, 28(9–10), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200067377

Carayannis, E., Hens, L., & Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P. (2017). Trans-disciplinarity and growth: Nature and characteristics of trans-disciplinary training programs on the human-environment interphase. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 8(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-015-0294-z

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8

Devecioglu, S., Sahan, H., Yildiz, M., Tekin, M., & Sim, H. (2012). Examination of socialization levels of university students engaging in individual and team sports. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 326–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.115

Dietschy, P. (2013). Making football global? FIFA, Europe, and the non-European football world, 1912–74. Journal of Global History, 8(2), 279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022813000223

Dolles, H., Söderman, S., Kern, A., Schwarzmann, M., & Wiedenegger, A. (2012). Measuring the efficiency of English Premier League football: A two-stage data envelopment analysis approach. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 2(3), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781211261502

Eisinger, P. (2002). Organizational capacity and organizational effectiveness among street-level food assistance programs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764002311005

Emrouznejad, A., & Yang, G. L. (2018). A survey and analysis of the first 40 years of scholarly literature in DEA: 1978–2016. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 61, 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2017.01.008

Espitia-Escuer, M., & García-Cebrián, L. I. (2010). Measurement of the efficiency of football teams in the champions league. Managerial and Decision Economics(6), 373. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1491

Espitia-Escuer, M., & Garcia-Cebrian, L. I. (2008). Measuring the productivity of Spanish first division soccer teams. European Sport Management Quarterly, 8(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740802224142

Falasca, M., & Kros, J. F. (2018) Intercollegiate athletics efficiency: A two-stage dea approach. Vol. 19. Applications of Management Science (pp. 3–19).

Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 120(3), 253–290. https://doi.org/10.2307/2343100

Ferkins, L., Shilbury, D., & McDonald, G. (2009). Board involvement in strategy: Advancing the governance of sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 23(3), 245–277.

Ferreira, J., Cardim, S., & Coelho, A. (2021). Dynamic capabilities and mediating effects of innovation on the competitive advantage and firm’s performance: The moderating role of organizational learning capability. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(2), 620–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00655-z

Fischer, R. L., Wilsker, A., & Young, D. R. (2011). Exploring the revenue mix of nonprofit organizations: Does it relate to publicness? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(4), 662–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010363921

Fletcher, D., & Arnold, R. (2011). A qualitative study of performance leadership and management in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(2), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.559184

Froelich, K. A. (1999). Diversification of revenue strategies: Evolving resource dependence in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28(3), 246–268.

Gheorghe, S. O. (2014). Preliminary Research Regarding the Implementation of Scientific Concepts in the Management of University Sports Clubs. Arena-Journal of Physical Activities, 3, 39–50.

Gheorghe, S. O., & Nicolae, M. (2015). The usage of benchmarking as a specific management method within the experimental research at university sport club. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180, 1330–1335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.273

Golden, L. L., Brockett, P. L., Betak, J. F., Smith, K. H., & Cooper, W. W. (2012). Efficiency metrics for nonprofit marketing/fundraising and service provision-A DEA analysis. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 10, 1.

González-Gómez, F., Picazo-Tadeo, A. J., & García-Rubio, M. Á. (2011). The impact of a mid-season change of manager on sporting performance. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 1(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781111107153

Green, M., & Collins, S. (2008). Policy, politics and path dependency: Sport development in Australia and Finland. Sport Management Review (sport Management Association of Australia & New Zealand), 11(3), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(08)70111-6

Guzmán, I. (2006). Measuring efficiency and sustainable growth in Spanish football teams. European Sport Management Quarterly, 6(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740601095040

Guzmán, I., & Morrow, S. (2007). Measuring efficiency and productivity in professional football teams: Evidence from the English Premier League. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 15(4), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-007-0034-y

Haas, D. (2003). Productive efficiency of English football teams—a data envelopment analysis approach. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24(5), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1105

Haas, D., Kocher, M. G., & Sutter, M. (2004). Measuring efficiency of German football teams by data envelopment analysis. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 12(3), 251.

Halkos, G. E., & Tzeremes, N. G. (2013). A two-stage double bootstrap DEA: The case of the top 25 European football clubs’ efficiency levels. Managerial and Decision Economics, 34(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2597

Hall, M., Andrukow, A., Barr, C., Brock, K., de Wit, M., Embuldeniya, D., & Malinsky, E. (2003). The capacity to serve - A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

Hansmann, H. B. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. The Yale Law Journal, 89(5), 835–901. https://doi.org/10.2307/796089

Hong, J. (2014). Data envelopment analysis in the strategic management of youth orchestras. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 44(3), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2014.937888

Hou, Y., Moynihan, D. P., & Ingraham, P. W. (2003). Capacity, management, and performance exploring the links. The American Review of Public Administration, 33(3), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074003251651

Ivašković, I. (2019). The stakeholder-strategy relationship in non-profit basketball clubs. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 32(1), 1457–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1638283

Johnes, J. (2006). Data envelopment analysis and its application to the measurement of efficiency in higher education. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.02.005

Kasale, L. L., Winand, M., & Robinson, L. (2018). Performance management of national sports organisations: A holistic theoretical model. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 8(5), 469–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-10-2017-0056

Kilpatrick, M., Hebert, E., & Bartholomew, J. (2005). College students’ motivation for physical activity: Differentiating men’s and women’s motives for sport participation and exercise. Journal of American College Health, 54(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.2.87-94

Klevenhusen, A., Coelho, J., Warszawski, L., Moreira, J., Wanke, P., & Ferreira, J. J. (2021). Innovation efficiency in OECD countries: A non-parametric approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(3), 1064–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00652-2

Kounetas, K. (2014). Greek football clubs’ efficiency before and after Euro 2004 victory: A bootstrap approach. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 22(4), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-013-0288-5

Lasby, D., & Sperling, J. (2007). Understanding the capacity of Ontario sports and recreation organizations. Imagine Canada.

Laurett, R., & Ferreira, J. J. (2018). Strategy in nonprofit organisations: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(5), 881–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9933-2

Lázaro, M. B., Espitia-Escuer, M., & García-Cebrián, L. I. (2014). Productivity in professional Spanish basketball. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 4(3), 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-07-2013-0024

Lee, S. P., Cornwell, T. B., & Babiak, K. (2013). Developing an instrument to measure the social impact of sport: Social capital, collective identities, health literacy, well-being and human capital. Journal of Sport Management, 27(1), 24–42.

Liu, S., Tu, C., & Wang, W. (2019). Study on the ecology effectiveness of community leisure sports based on data envelopment analysis. Ekoloji, 28(107), 1445–1450.

Madella, A., Bayle, E., & Tome, J. (2005). The organisational performance of national swimming federations in Mediterranean countries: A comparative approach. European Journal of Sport Science, 5(4), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390500344644

Margaritis, S. G., Tsamadias, C. P., & Argyropoulos, E. E. (2021). Investigating the relative efficiency and productivity change of upper secondary schools: The case of schools in the region of Central Greece. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00698-2

Masoumi, H., Ghanjouei, F. A., Dashgarzade, K., & Javadi, S. (2013). Presentation of an entropy decision making pattern to develop a comprehensive external evaluation model of sporting federations’ performance using fuzzy approach. World Applied Sciences Journal, 22(12), 1718–1728. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.22.12.378

Mikušová, P. (2015). An application of DEA methodology in efficiency measurement of the Czech public universities. Procedia Economics and Finance, 25, 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00771-6

Miragaia, D., Brito, M., & Ferreira, J. (2016). The role of stakeholders in the efficiency of nonprofit sports clubs. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21210

Miragaia, D., Ferreira, J., & Carreira, A. (2014). Do stakeholders matter in strategic decision making of a sports organization? Revista De Administração De Empresas, 54(6), 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020140605

Miragaia, D., Martins, C., Kluka, D., & Havens, A. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, social entrepreneurship and sport programs to develop social capital at community level. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 12(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-015-0131-x

Mirfakhr-al-Dini, S., & Khatibi-Aghda, A. (2011). Measuring the performance of sport associations in attracting individuals to sports using data envelopment analysis. A case study in the Yazd City (Iran) in 2008. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(10), 829–837.

Misener, K., & Doherty, A. (2009). A case study of organizational capacity in nonprofit community sport. Journal of Sport Management, 23(4), 457–482.

Misener, K., & Doherty, A. (2013). Understanding capacity through the processes and outcomes of interorganizational relationships in nonprofit community sport organizations. Sport Management Review, 16(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.07.003

Picazo-Tadeo, A. J., & González-Gómez, F. (2010). Does playing several competitions influence a team’s league performance? Evidence from Spanish professional football. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 18(3), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-009-0117-z

Popa, M. (2013). Strategies of optimizing the elements of Romanian university sports. Strategii de Optimizare a Elementelor Componente Ale Sportului Universitar Românesc., 14(2), 100–106.

Popeska, B., Barbareev, K., & Ivanovska, E. J. (2015). Organization and realization of university sport activities in Goce Delcev University - Stip. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 2293–2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.256

Sakires, J., Doherty, A., & Misener, K. (2009). Role ambiguity in voluntary sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 23(5), 615–643.

Seippel, Ø. (2006). Sport and social capital. Acta Sociologica, 49(2), 169–183.

Seo, J. (2020). Resource dependence patterns, goal change, and social value in nonprofit organizations: Does goal change matter in nonprofit management? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(2), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318778782

Shaw, E. H. (2009). A general theory of systems performance criteria. International Journal of General Systems, 38(8), 851–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081070903270543

Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (2007). Estimation and inference in two-stage, semi-parametric models of production processes. Journal of Econometrics, 136(1), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2005.07.009

Škorić, S., & Bartoluci, M. (2014). Planning in the Croatian national sport federations. Planiranje u Hrvatskim Nacionalnim Sportskim Savezima, 46, 119–125.

Speckbacher, G. (2008). Nonprofit versus corporate governance: An economic approach. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 18(3), 295–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.187

Terrien, M., Scelles, N., Morrow, S., Maltese, L., & Durand, C. (2017). The win/profit maximization debate: Strategic adaptation as the answer? Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 7(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-10-2016-0064

Valério, R. P., & Angulo-Meza, L. (2013). A data envelopment analysis evaluation and financial resources reallocation for Brazilian olympic sports. WSEAS Transactions on Systems, 12(12), 627–636.

Villa, G., & Lozano, S. (2018). Dynamic network DEA approach to basketball games efficiency. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 69(11), 1738–1750. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2017.1409158

Weiss, O. (2010). University sports: Major development and new perspectives. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 48(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10141-010-0007-z

Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2011). Scarcity of resources in German non-profit sport clubs. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 188–201.

Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2013). Understanding the importance of organizational resources to explain organizational problems: Evidence from nonprofit sport clubs in Germany. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(2), 461–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9272-2

Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2014). Examining the financial condition of sport governing bodies: The effects of revenue diversification and organizational success factors. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(4), 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9387-0

Wicker, P., Breuer, C., & Hennigs, B. (2012). Understanding the interactions among revenue categories using elasticity measures—Evidence from a longitudinal sample of non-profit sport clubs in Germany. Sport Management Review, 15(3), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.12.004

Winand, M., Vos, S., Zintz, T., & Scheerder, J. (2013). Determinants of service innovation: A typology of sports federations. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 13(1–2), 55–73.

Winand, M., Zintz, T., Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2010). Organizational performance of olympic sport governing bodies: Dealing with measurement and priorities. Managing Leisure, 15(4), 279–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2010.508672

Winand, M., Zintz, T., & Scheerder, J. (2012). A financial management tool for sport federations. Sports, Business and Management, 2(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781211261539

Wu, H., Chen, B., Xia, Q., & Zhou, H. (2013). Ranking and benchmarking of the Asian games achievements based on dea: The case of Guangzhou 2010. Asia-Pacific Journal of Operational Research, 30(6). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217595913500280

Young, D. (2007). Why study nonprofit finance. AltaMira Press.

Young, D. (2011). The prospective role of economic stakeholders in the governance of nonprofit organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22(4), 566–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9217-1

Zelenkov, Y. A., Tsvetkov, V. A., & Solntsev, I. V. (2017). Comparative assessment of the effectiveness of sports development in the Russian regions on the basis of DEA method. Economy of Region, (4), 1184–1198. https://doi.org/10.17059/2017-4-17

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This study, through NECE–Research Unit in Business Sciences, is funded by the Multiannual Funding Programme of R&D Centres of FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under the project “UIDB/04630/2020”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miragaia, D.A.M., Ferreira, J.J.M. & Vieira, C.T. Efficiency of Non-profit Organisations: a DEA Analysis in Support of Strategic Decision-Making. J Knowl Econ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01298-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01298-6